Abstract

Near-infrared fluorescent proteins (NIR FPs) engineered from bacterial phytochromes (BphPs) are of great interest for in vivo imaging. They utilize biliverdin (BV) as a chromophore, which is a heme degradation product, and therefore they are straightforward to use in mammalian tissues. Here, we report on fluorescence properties of NIR FPs with key alterations in their BV binding sites. BphP1-FP, iRFP670 and iRFP682 have Cys residues in both PAS and GAF domains, rather than in the PAS domain alone as in wild-type BphPs. We found that NIR FP variants with Cys in the GAF or with Cys in both PAS and GAF show blue-shifted emission with long fluorescence lifetimes. In contrast, mutants with Cys in the PAS only or no Cys residues at all exhibit red-shifted emission with shorter lifetimes. Combining these results with previous biochemical and BphP1-FP structural data, we conclude that BV adducts bound to Cys in the GAF are the origin of bright blue-shifted fluorescence. We propose that the long fluorescence lifetime follows from (i) a sterically more constrained thioether linkage, leaving less mobility for ring A than in canonical BphPs, and (ii) that π-electron conjugation does not extend on ring A, making excited-state deactivation less sensitive to ring A mobility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Near-infrared (NIR) fluorescent proteins (FPs) are of great interest for in vivo imaging of mammals. Because an optical transparency window of mammalian tissues exists in the NIR region, 650–900 nm, where water, hemoglobin and melanin absorptions are minimal1,2, noninvasive deep-tissue imaging can be achieved with NIR FPs. So far, many kinds of GFP-based FPs have been engineered and applied to real-time optical imaging in life sciences3. However, probably due to the limitation of the extent of the conjugated π-electron system, the absorption in engineered GFP-like proteins is limited to about 610 nm4,5 and fluorescence emission to about 675 nm6.

Phytochromes are red-light absorbing photoreceptors using bilin chromophores7,8,9. The first fluorescent phytochrome, derived from the cyanobacterial phytochrome Cph1 was reported by Fischer and Lagarias10. Subsequently, NIR FPs have been engineered from bacterial phytochromes (BphPs), derived from Deinococcus radiodurans DrBphP11,12 and Rhodopseudomonas palustris RpBphP1,13,14,15,16. BphPs bind a biliverdin (BV) tetrapyrrole compound, which is a heme degradation product. Therefore, BV is endogenously present in all mammalian tissues11,17, which allows to use BphP-derived NIR FPs as easily as GFP-like FPs, without adding chromophore exogenously. The photosensory core of phytochromes comprises three domains: PAS, GAF and PHY. The PAS-GAF fragment, which has a molecular weight of about 35 kDa in the monomeric form16, is adequate for chromophore binding. BphPs have a Cys residue in the PAS domain that covalently binds to BV via the C32 atom in ring A18,19. In the dark, canonical BphPs adopt a 670–690 nm absorbing state known as the Pr state. Upon irradiation at these wavelengths, BphPs undergo photoisomerization in C15=C1620,21, resulting in a photoproduct Lumi-R22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30, which then thermally relaxes to a 740–760 nm absorbing state termed Pfr31.

In recent years, several blue-shifted bright NIR FPs have been engineered from wild-type RpBphP1, RpBphP2, and RpBphP615, such as BphP1-FP (the brightest FP among current BphP-derived NIR FPs)16, iRFP68214 and iRFP67014, respectively. In these NIR FPs, the PHY domain was truncated, and photoisomerization was blocked through mutation of key residues in the GAF domain. Furthermore, a Cys residue was introduced in the GAF domain: Cys253 in BphP1-FP, Cys244 in iRFP670 and Cys249 in iRFP682, enabling BV to covalently bind to cysteine residues in the PAS and GAF domains14,15. These Cys residues in the GAF domain of BphP1-FP, iRFP670 and iRFP682 were introduced at the same position as the conserved Cys residues in plant and cyanobacterial phytochromes, which bind phycocyanobilin (PCB) or phytochromobilin (Pϕ, capical B)7 (Fig. S1). The blue-shifted NIR FPs have been successfully used in deep-tissue imaging and, moreover, enabled multicolor in vivo imaging14,32,33.

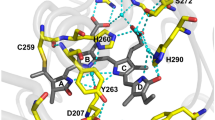

More recently, a crystal structure of BphP1-FP/C20S variant has been determined16. BV binds to Cys253 in the GAF domain in two ways, either via the C31 atom or via the C32 atom in an approximate 1:1 stoichiometry (Fig. 1). The unique chromophore species that result from this binding appear to be responsible for the spectral blue shift and the high fluorescence quantum yield. Yet, real-time studies of the picosecond dynamics on the excited states are required to understand molecular mechanisms of fluorescence more deeply.

Here we report the ultrafast photodynamics in BphP1-FP, iRFP670 and iRFP682 with femtosecond transient absorption and picosecond fluorescence spectroscopy. Furthermore, we analyze the ultrafast dynamics in their mutants that have a Cys residue in the GAF or PAS domains, or no Cys at all. We aim to gain insights into the molecular origin of the blue-shifted and bright BphP1-FP fluorescence, combining ultrafast spectroscopic results with previous biochemical and structural analyses. Elucidation of the molecular mechanisms of fluorescence emission should give insight into rational design of enhanced NIR-FPs with higher quantum yield and various absorption and emission wavelengths.

Methods

Protein expression and purification

The BphP1-FP, iRFP670 and iRFP682 genes were cloned into the pBAD/His-B vector (Invitrogen). Site-specific mutagenesis was performed using QuikChange kit (Stratagene). The proteins with polyhistidine tags on the N-termini were expressed in LMG194 bacterial cells (Invitrogen) bearing the pWA23h plasmid encoding heme oxygenase under the rhamnose promoter14. To initiate protein expression, bacterial cells were grown in RM medium supplemented with ampicillin, kanamycin and 0.02% rhamnose for 5 h at 37 °C. Then 0.002% arabinose was added and bacterial culture was incubated for additional 12 h at 37 °C followed by 24 h at 18 °C. Proteins were purified using Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen). Ni-NTA elution buffer contained no imidazole and 100 mM EDTA. The elution buffer was substituted with PBS buffer using PD-10 desalting columns (GE Healthcare). For spectroscopic experiments, the samples were diluted in PBS buffer composed of 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4 and 2 mM KH2PO4 at pH 7.4.

Steady state absorption and fluorescence spectroscopy

Steady-state absorption spectra were recorded using a UV/Vis spectrometer (Cary 4000, Agilent) at room temperature (~20 °C). The samples were diluted with PBS buffer (pH 7.4) and measured in a 1 mm pathlength quartz cuvette (100-QS, Hellma Analytics). Steady-state fluorescence spectra were measured with a Vis/Near-IR spectrometer (FluoroMax, Horiba) at the room temperature (~20 °C). The samples were diluted to an absorbance of 0.1 per cm to prevent reabsorption and measured in a 10 mm pathlength PMMA cuvette (759150, Brand). The excitation wavelength was 600 nm for the fluorescence measurements.

Femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy

Femtosecond transient absorption measurements were performed with a femtosecond pump-probe setup described previously34,35 at room temperature (~20 °C). A seed pulse from a Ti:Sapphire oscillator (Vittesse, Coherent; 800 nm, 82 MHz, 50 fs) was amplified to 4.5 W by using a Ti:Sapphire regenerative amplifier (Libra, Coherent; 800 nm, 1 kHz, 35 fs) with a Nd:YLF Q-switched high-power pump laser (Evolution, Coherent; 527 nm, 1 kHz). The beam was split into two paths as for pump and probe respectively. On the pump path, the beam was guided into an optical parametric amplifier (OPerA Solo, Coherent) to generate tunable pulses for excitation, and focused on the sample with a diameter of 150 μm. The pump pulse was progressively delayed with respect to the probe using a 60 cm long delay stage (IMS-6000, Newport) to cover a time window up to ~4 ns. The excitation wavelengths were selected as 590 nm, 630 nm, 640 nm or 660 nm depending on the sample. Narrow band interference filters (Δλ~10 nm) for the excitation wavelengths were inserted on the pump path. On the probe path, the beam was attenuated and focused on a 2 mm sapphire plate to generate white light for probing. A spectral range of 530–830 nm of the white light probe pulse was detected by a 256-segment photodiode array36. The polarization of pump and probe was set at the magic angle (54.7°). The samples in 1-mm cuvettes (100-QS, Hellma Analytics) with an absorbance of 1.5 per cm at the absorption maximum were set on a home-built vibrating sample holder in order to avoid damage to the samples.

Picosecond time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy

Time-resolved fluorescence measurements were carried out with a streak camera setup, as described previously37,38,39 at room temperature (~20 °C). Femtosecond laser pulses from an integrated Ti:Sapphire oscillator (Vitesse, Coherent, 800 nm, 80 MHz, 100 fs) was incorporated into a Ti:Sapphire regenerative amplifier (RegA, Coherent, 800 nm, 50 kHz, 100 fs). The beam was input to an optical parametric amplifier (OPA9400, Coherent) to create tunable excitation pulses. The excitation pulse was focused on a 3 mm pathlength quartz cuvette (102.251-QS, Hellma Analytics). The samples had an absorbance of 0.25 per cm at their absorbance maximum. The samples were excited at 590 nm, 630 nm, 640 nm or 660 nm. A narrowband interference filter (Δλ~10 nm) for respective excitation wavelength was located on the pump path. The applied excitation pulse energy was ~4 nJ, and the polarization between the excitation beam and emission was set at the magic angle (54.7°). Fluorescence from the sample was collected perpendicularly to the pump beam and focused into a slit using an achromatic lens and the wavelengths were resolved by a spectrograph (250IS, Chromex). Wavelength-resolved fluorescence was converted to electrons at the photocathode and a variable voltage was applied to sweep electrodes to collect the time-resolved fluorescence spectra on a streak camera (C5680, Hamamatsu).

Data analysis

Global analysis was performed for the transient absorption spectra using the Glotaran program35,40. With global analysis, all wavelengths are analyzed simultaneously with a set of common time constants41. A kinetic model was applied consisting of sequentially interconverting, evolution-associated difference spectra (EADS), i.e. 1 → 2 → 3 → … in which the arrows indicate successive mono-exponential decays of a time constant, which can be regarded as the lifetime of each EADS41. The first EADS corresponds to the difference spectrum at time zero. The first EADS evolves into the second EADS with time constant τ1, which in turn evolves into the third EADS with time constant τ2, etc. The procedure clearly visualizes the evolution of the intermediate states of the protein42. Decay-associated difference spectra (DADS) indicate the spectral changes with parallel decay channels and independent decay time constants. It is important to note that parallel and sequential analysis are mathematically equivalent and yield identical time constants39. The transient fluorescent spectra were analyzed with parallel decaying components, which yield decay associated spectra (DAS)41. The standard errors in time constants were 2–5% the transient absorption data, and less than 1% for the transient fluorescence data in each decay component.

Results

Steady-state absorption and fluorescence spectroscopy

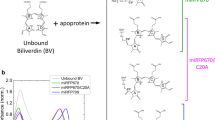

Steady-state absorption and fluorescence spectra of BphP1-FP and its C20S, C253I, C20S/C253I mutants are shown in Fig. 2a,b. The absorption of BphP1-FP and BphP1-FP/C20S peaks around 640 nm, while the other two mutants have maximum absorption around 670 nm. Fluorescence spectra of BphP1-FP and BphP1-FP/C20S have a maximum around 670 nm, while fluorescence of mutants BphP1-FP/C253I and BphP1-FP/C20S/C253I have a maximum around 700 nm. Compared to the wild-type RpBphPs, which absorb at around 700 nm and fluoresce around 720 nm19,39,43,44,45, both of the absorptions and fluorescence of BphP1-FP and BphP1-FP/C20S has been strongly blue-shifted by about 60 nm. For mutants BphP1-FP/C253I and BphP1-FP/C20S/C253I, only moderate blue-shifts of absorption and fluorescence by ~20–30 nm were observed. In BphP1-FP and BphP1-FP/C20S, broader absorption was observed on the red edge compared to BphP1-FP/C253I and BphP1-FP/C20S/C253I. Similar observations were made in iRFP670 and iRFP682 and their corresponding mutants (Fig. S2). These results are consistent with previous work14,16,46.

Time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy

Picosecond time-resolved and spectrally resolved fluorescence spectroscopy was conducted to investigate the emission processes on BphP1-FPs, iRFP670 and iRFP682. Selected time-resolved emission spectra and decay associated spectra (DAS) on BphP1-FP are shown in Fig. 3. The excitation wavelength was 640 nm. Two exponential decay components were required for the fitting: τf2 (1.56 ns) with a DAS peaking around 670 nm and τf1 (0.35 ns) with its DAS peaking around 700 nm. The blue component τf2 was dominant on the emission process, with amplitude of about 93% of the initially excited molecules.

Experiments on the BphP1-FP/C20S mutant gave very similar results to BphP1-FP, with a minor short-lifetime emission component τf1 (0.34 ns) at around 700 nm, and a dominant long-lifetime component τf2 (1.47 ns) at 670 nm (Fig. 4a). On the other hand, for the BphP1-FP/C253I and BphP1-FP/C20S/C253I mutants, no 670 nm emission was observed (Fig. 4b,c). In BphP1-FP/C253I, two emission components decaying with 0.26 ns (centered at 700 nm) and 0.88 ns (centered at 710 nm) were observed. Meanwhile, in BphP1-FP/C20S/C253I, two emission components centered at 700 nm decaying with 0.26 ns and 0.93 ns were observed.

Results for iRFP670 and iRFP682 are presented in Fig. 5, with global fitted time constants and DAS. Blue-shifted and long-lifetime components were observed only in iRFP670, iRFP670/C10A, iRFP682 and iRFP682/C15S. On the other hand, in the iRFP670/C244S, iRFP670/C10A/C244S, iRFP682/C15S and iRFP682/C15S/C249S mutants, only red-shifted and shorter-lifetime components were found, similar to the corresponding BphP1-FP mutants (Figs S3 and S4).

The time-resolved emission spectra shown in Figs 3 and 4 demonstrate that BphP1-FP, which has Cys253 in the GAF domain and Cys20 in the PAS domain, has a dominant fluorescence component (>90% amplitude) with a blue-shifted emission at 670 nm and long fluorescence lifetime of 1.56 ns. The experiments on the cysteine mutants clearly demonstrate that this blue-shifted, long-lived emission arises from BV bound to Cys253 in the GAF domain: upon deletion of Cys20 in the PAS domain, the emission wavelength and lifetime remains essentially the same. Upon deletion of Cys253 in the GAF domain, only shorter-lived emission components around 700–710 nm are observed. For iRFP670 and iRFP682 and their cysteine mutants, similar results were obtained although their fluorescence lifetimes were somewhat shorter than in BphP1-FP.

The BphP1-FP/C20S/C253I mutant shows weak fluorescence at 700 nm (decay with 0.26 ns and 0.93 ns, Fig. 4) even though it does not have a covalent bond with a cysteine according to the zinc staining16. This observation implies that BV has been incorporated non-covalently into the GAF domain pocket18, and has a red-shifted fluorescence component at 700 nm. The two fluorescence species of BphP1-FP/C253I at 710 nm and 700 nm are assigned to a BV covalently bound to Cys20 and a BV that non-covalently incorporated into the protein, respectively. In the corresponding Cys mutants of iRFP670 and iRFP682, the same characteristics were observed (Figs S3 and S4, ref. 46 for the zinc staining).

Transient absorption spectroscopy

Femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy was performed to characterize the primary photoreactions in BphP1-FP, iRFP670, iRFP682 and their mutants. Figure 6a shows raw transient absorption spectra in BphP1-FP at selected delay times with excitation at 640 nm. These data were globally fitted with three components, with lifetimes of τa1 (7.6 ps), τa2 (0.20 ns) and τa3 (1.52 ns), and the resulting EADS and DADS are shown in Fig. 6b,c, respectively. For the BphP1-FP mutants, transient absorption spectra were fitted with three components as well (Fig. S5). The negative ΔA signal in Fig. 6b between 570–670 nm originates from ground state bleaching (GSB), and the positive ΔA signals around 530 nm and 700 nm indicate excited state absorption (ESA). As it can be seen from the EADS and DADS in Fig. 6c, the 1.52 ns component was clearly dominant and indicates loss of excited states, in agreement with the streak camera results. The 0.20 ns component denotes a minor excited-state decay component and corresponds to the minor 0.35 ns component from the streak camera experiments (Fig. 3b). In the early time range, transient absorption spectra only slightly changed with a time constant of 7.6 ps, which is interpreted as a relaxation process in the excited state27.

The global analysis indicates that no long-lived species are formed in the BphP1-FP (Fig. 6b,c) in contrast to wild-type RpBphPs that form the photoproduct Lumi-R27,39. In agreement, time traces at selected wavelengths on transient absorption spectra of BphP1-FP are shown in Fig. 6d, clearly showing that the transient absorption signal almost completely decayed in 3 ns. These observations indicate that the BV C15=C16 photoisomerization that in native BphPs results in Lumi-R formation has been successfully impeded.

Similarly to BphP1-FP, three time constants were required to adequately describe the transient absorption data of iRFP670 and iRFP682, with 3.2 ps, 0.08 ns and 1.08 ns in iRFP670, and with 3.5 ps, 0.12 ns and 1.12 ns in iRFP682 (Fig. 7). Furthermore, three components were required to fit iRFP670/C10A, iRFP670/C10A/C244S, iRFP682/C15S, iRFP682/C249S as were the mutants of BphP1-FP (Figs S3 and S4). In iRFP670/C244S and iRFP682/C249S, two components were sufficient for global fitting with time constants of ~10 ps and ~0.6 ns.

The shape of the transient absorption spectra reported here merits some discussion. A pronounced ESA band near 700 nm that is red-shifted with respect to the ground state absorption is observed in BphP1-FP (Fig. 6) and iRFP670 (Fig. 7a) and their cysteine mutants, (Figs S3a,c,e and S5) and iRFP682 (Fig. 7b), while in the cysteine mutants of iRFP682 no or very little of such absorption is observed (Fig. S4a,c,e). The time evolution of the ΔA signal around 700 nm is indistinguishable from the ESA at 530 nm (Fig. S6), which solidifies the assignment of this signal to ESA. Almost all biliproteins show such a structured ESA at varying intensities, in phytochromes23,27,28,39,47 as well as biliprotein light harvesting antennae48. Such ESA may either be red-shifted, blue-shifted, or overlap with respect to the ground state absorption. Even among BphPs of the same species (R. palustris) and iRFPs derived thereof, the spectral position of the ESA has been shown to vary significantly27,39,47. In previous work it was demonstrated for RpBphP2 and RpBphP3 that the spectral position of this ESA is highly sensitive to the protein matrix, involving interactions between BV ring D with charged and hydrogen-bonding amino acid side chains:27 In the case of the iRFP682 cysteine mutants (Fig. S4a,c,e), the ESA either has a low amplitude or absorbs near the Pr absorption maximum, and is therefore entirely compensated by the ground state bleach and stimulated emission. Note that in plant phytochrome, such apparent absence of ESA was also observed22.

Because of the aforementioned variability of ESA in the transient absorption spectra, which compensates the ground state bleach and stimulated emission in an unpredictable manner, one cannot reliably associate the minima, maxima and zero crossings in the transient absorption spectra of Figs 6, 7, S3, S4 and S5 with the distinct spectral forms as observed in time-resolved fluorescence. For this reason, we make such assignments exclusively on the basis of the time-resolved fluorescence streak camera results. Given that the short-lived minor decay components in the transient absorption data have similar time constants as those derived from the streak camera, we conclude that they probably arise from the red-shifted population.

Furthermore, one may consider the possibility that the strong absorption near 700 nm could be due to a primary ground-state photoproduct, given that the canonical photoproduct Lumi-R (which has isomerized from the 15Za conformer to 15Ea) is expected to absorb near such wavelengths. We will show here that this is not the case. First, we note that the transient absorption and the streak camera experiments agree on the measured lifetimes, so we can assign the time constants in the transient absorption clearly to excited-state decay, and not ground-state product decay. Thus, if a transient product would be formed it would need to coexist with the singlet excited state during the fluorescence lifetime. With these conditions, the idea that the positive band arises from a primary photoproduct is highly unlikely, given that the 700 nm absorption rises within the instrument response of 100 fs. If it were a primary photoproduct, it would have to be formed in less than ~50 fs. It is well-established that in wild type phytochromes, the isomerized Lumi-R product rises on a much slower timescale of tens to hundreds of picoseconds from the Pr state22,23,24,27,29,39. Even if this were to happen, this putative product would then fortuitously need to have a lifetime that is exactly the same as the singlet excited state lifetime. We note that the biliprotein light harvesting antenna PC645 from cryptophyte algae shows a similar transient absorption signal red-shifted with respect to the ground state48, very similar to that of BphP1-FP. These type of light harvesting antennae have evolved for optimal light harvesting and show no transient photoproducts of their bilin chromophores whatsoever. Thus, we may safely conclude that the 700 nm transient absorption band corresponds to excited-state absorption, and not to a ground-state photoproduct.

Kinetic isotope effects on the fluorescent lifetime

To investigate the fluorescence deactivation mechanisms in the presently studied NIR FPs, time-resolved fluorescence experiments in H2O and D2O solutions were conducted. Figure 8 shows DAS and time traces on BphP1-FP in H2O and D2O with 640 nm excitation. The DAS in H2O and D2O are almost identical, but the time constants are significantly different: 0.35 ns and 1.56 ns in H2O, and 0.48 ns and 2.89 ns in D2O. The H/D kinetic isotope effects (KIEs), defined as the fluorescence lifetime in D2O divided by the lifetime in H2O, on τa1 and τa2 on BphP1-FP were 1.4 and 1.9, respectively. For the BphP1-FP/C20S, C253I and C20S/C253I mutants, significant KIEs were observed as well (Table S1). Moreover, significant H/D KIEs were observed in iRFP670, iRFP682 and their mutants (Fig. S7 and Table S1). In the time region shorter than ~0.8 ns, a longer lifetime carries a larger KIE as in other iRFPs47 and wild-type BphPs27,39. On the other hand, a KIE of ~1.8 was observed for all lifetimes longer than ~0.8 ns (Fig. S8). The values of the large KIEs correspond to those of other red-shifted NIR FPs: iRFP702, iRFP713 and iRFP72047. The transient absorption data showed similar isotope effects (Table S1).

Significant KIEs were detected in fluorescence decays (Figs 8, S7 and S8) consistent with those of other iRFPs47, wild-type BphPs and their point mutants27,39, indicating that excited state proton transfer (ESPT) may constitute a significant non-radiative decay process, as discussed before27,39,47,49. Furthermore, KIEs in blue-shifted BphP1-FP (KIE: 1.9), iRFP670 (1.7) and iRFP682 (1.7) are as large as red-shifted iRFP702 (1.8), iRFP713 (1.8) and iRFP720 (1.9) while lifetimes of the blue-shifted NIR FPs are approximately twice larger47, which could imply that that the deactivation mechanism of the blue-shifted NIR FPs is similar to that of the red-shifted NIR FPs.

Discussion

Molecular basis for blue-shifted long-lived fluorescence in engineered bacterial phytochromes

Our results have shown that the fluorescence of BphP1-FP is blue-shifted, bright and long-lived as compared to that of other native and engineered BphPs, which confers important advantages on this type of fluorescent proteins for in vivo multicolor imaging. We now discuss the molecular basis of these key properties. In previous work on BphP1-FP/C20S, its high-resolution X-ray structure was reported16. In that work, two distinct models of BV binding to Cys253 in the GAF domain were proposed, i.e. via the BV C32 atom (1, Fig. 1a) and via the BV C31 atom (2, Fig. 1b) in a ~1:1 stoichiometric ratio16. In contrast, the native BV adduct of the the similar RpBphP3 protein (3, Fig. 1c) binds BV to Cys28 in the PAS domain. In both BV adducts of BphP1-FP/C20S, the C3 atom is sp3 hybridized resulting in an upward orientation of its substituent toward Cys253, and hence does not form the double bond with C31 or C2 that is present in native bacterial phytochromes19,43,45. This molecular structure implies that the π-conjugated system of both BV adducts becomes shorter by one double bond as compared to BV bound to native bacterial phytochrome (cf. 1 and 2 vs. 3, Fig. 1) and consequently, their absorption is 30–40 nm blue-shifted. In fact, the proposed conjugated π-electron system is identical to that of PCB or PФB bound to plant or cyanobacterial phytochromes50,51, and accordingly their absorption and emission maxima are nearly identical10,22. Recent work on the terminal phycobilisome emitter LCM demonstrated a ZZZssa conformation for its PCB chromophore, like that in phytochrome, with its absorption and emission wavelength maxima very similar to that of BphP1-FP, plant and cyanobacterial phytochrome52. This indicates that the conjugated π-electron system of the chromophore constitutes the main determinant of absorption (~640–650 nm) and emission maxima (~670 nm), with a minor contribution from the specific protein environment.

There should be two distinct blue-shifted emissions from BV binding to Cys253 via C31 and C32, whereas only one component is observed. Apparently, the two fluorescent species have emission spectra and lifetime too close to each other to be resolved in the time resolved measurements. This is likely the case because (i) the emission wavelength is mainly determined by the π-electron conjugation, which identical in both cases and to a lesser extent by pigment-protein interactions, which are highly similar for both cases, and (ii) the lifetime is mainly determined by pigment-protein interactions in the binding pocket to rings B, C and D, which is highly similar in both cases. We further note that in BphP1-FP and its C20S mutant, the steady-state absorption spectra (Fig. 2), transient fluorescence spectra (Figs 3b and 4a) and transient absorption spectra (Figs 6b and S5a) are almost identical. These spectra reflect structures of BV adducts in the protein, suggesting that BV in BphP1-FP forms almost the same adducts as in BphP1-FP/C20S. In other words, BphP1-FP has BV that forms a covalent bond with Cys253 in the GAF in two ways via C31 and via C32, but hardly binds Cys20 in the PAS domain. Possibly, the minor red-shifted species of BphP1-FP and its C20S mutant with weak 700-nm fluorescence originated from non-covalent BV-protein complex, like in the C20S/C253I mutant. Similar conclusions apply to iRFP670 and iRFP682 (Figs 7, S3 and S4).

Taken together, the static and time-resolved spectroscopic data on BphP1-FP and its mutants the 3D X-ray structural data16 and biochemical data16 indicate that the blue-shifted species of BphP1-FP are derived from the BV adducts covalently bound to Cys253 in the GAF domain via C31 and via C32.

Fluorescence lifetime, quantum yield and protein design opportunities

The BphP1-FP fluorescence lifetime of 1.56 ns is by far the longest reported on BV-binding bacterial phytochromes27,39,47,53, and, in fact, is almost identical to that of allophycocyanin (APC)54,55, a cyanobacterial photosynthetic light harvesting complex that binds PCB in a ZZZasa configuration56. This notion is interesting because APC has been optimized through natural evolution for optimal resonant energy transfer, and the same molecular parameters need to be optimized for resonant energy transfer and fluorescence. The phycobilisome terminal emitter LCM, which transfers energy to the chlorophylls in the photosynthetic membrane, binds PCB in a ZZZssa configuration as in phytochromes52 and has a fluorescence lifetime of 1.2 ns57. The BphP1-FP fluorescence lifetime is almost as long as that of the intensely fluorescent Y176F mutant of cyanobacterial phytochrome Cph1 (1.8 ns)10,58, which binds PCB and is therefore not readily genetically encodable for in vivo fluorescence.

The blue-shifted fluorescence components of BphP1-FP, iRFP670 and iRFP682 have a higher quantum yield than red-shifted NIR FPs11,14. BphP1-FP has the highest quantum yield (~13%)16 and corresponding long fluorescence lifetime (1.56 ns) among the blue-shifted NIR FPs, which is twice higher than e.g. iRFP713 (~6.3%)14. The blue-shifted NIR FPs have a chromophore-binding Cys residue in the GAF domain, while the red-shifted NIR FPs have the chromophore-binding Cys only in the PAS domain, which clearly indicates that covalent binding of BV to the Cys in the GAF (via C31 and C32) is a key condition to achieve the high fluorescence quantum yield. Theoretical studies have indicated that ring A and ring D rotation followed by internal conversion constitute major causes of excited-state deactivation in bilin chromophores59, that will form an effective channel to deactivate fluorescence in NIR FPs and wild-type BphPs. Considering the above, two plausible factors may contribute to the higher fluorescence quantum yield of the proteins studied here: (i) the BV C31/C32 –Cys adduct in the GAF domain is sterically more constrained and leaves less mobility for ring A and by extension, the A-B methine bridge than in BphPs with the BV–Cys adduct in the PAS domain; (ii) differently from the red-shifted NIR FPs and wild-type BphPs, the π-electron conjugated system does not extend on the ring A in BphP1-FP (Fig. 1). Consequently, any ring A rotation will affect the π-electron conjugated system to a lesser extent than in traditional BphPs.

So far, most efforts to optimize the fluorescence quantum yield of BphP-based NIR FPs have been focused on restricting the motion of the BV D ring13,14,60. Here, we find that restricting ring A motion and/or locking out ring A from the conjugated system increases the fluorescence quantum yield. This result suggests that in general, restricting ring A mobility in red-shifted fluorescent BphP derivatives may prove beneficial for achieving higher brightness. This proposal seems to contradict an earlier study on BphPs with locked BV chromophores61, where restricting the motion of ring A did not have a signifcant effect on the fluorescence quantum yield. However, in those studies, the quantum yields were comparably low (<0.01), which implies that other pathways including ring D motion contributed to the fluorescence decay. It suggests that for a BphP with a low fluorescence quantum yield, ring D motion is limiting the fluorescence. We propose that as ring D is locked down by genetic engineering with a resulting higher fluorescence quantum yield, ring A motion becomes a limiting factor for the fluorescence quantum yield. In addition ESPT, which probably is in effect independently from ring D or A motion47, may limit the fluorescence quantum yield for longer fluorescence lifetimes27,39,47.

Conclusions

We have systematically characterized the excited state dynamics and fluorescence deactivation mechanisms in the RpBphP-derived blue-shifted NIR FPs: BphP1-FP, iRFP670, iRFP682, and their Cys mutants in the PAS and GAF domains. The substantially prolonged lifetimes and enhancement of fluorescence intensity were identified in the blue-shifted NIR FP variants, while the isomerization processes were found to be completely blocked. In the time-resolved fluorescence spectra, a distinct blue-shifted emission with a long lifetime was identified. Combining the results from ultrafast spectroscopy with the crystal structure of the BphP1-FP/C20S mutant and mutational analysis of the relevant Cys residues we assign the bright blue-shifted fluorescent species to two BV adducts, which are covalently bound to the Cys residue in the GAF domain. Our results explain the origin of high fluorescence quantum yield and blue-shifted spectra in NIR FPs with these BV adducts. Overall, these findings provide significant insights for the rational design of brighter and multicolor NIR FPs from a variety of wild-type BphPs.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Hontani, Y. et al. Bright blue-shifted fluorescent proteins with Cys in the GAF domain engineered from bacterial phytochromes: fluorescence mechanisms and excited-state dynamics. Sci. Rep. 6, 37362; doi: 10.1038/srep37362 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Piatkevich, K. D., Subach, F. V. & Verkhusha, V. V. Engineering of bacterial phytochromes for near-infrared imaging, sensing, and light-control in mammals. Chemical Society reviews 42, 3441–3452, doi: 10.1039/c3cs35458j (2013).

Weissleder, R. & Ntziachristos, V. Shedding light onto live molecular targets. Nature medicine 9, 123–128, doi: 10.1038/nm0103-123 (2003).

Piatkevich, K. D. & Verkhusha, V. V. Advances in engineering of fluorescent proteins and photoactivatable proteins with red emission. Current opinion in chemical biology 14, 23–29, doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.10.011 (2010).

Morozova, K. S. et al. Far-red fluorescent protein excitable with red lasers for flow cytometry and superresolution STED nanoscopy. Biophysical journal 99, L13–L15, doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.04.025 (2010).

Drobizhev, M., Tillo, S., Makarov, N. S., Hughes, T. E. & Rebane, A. Color hues in red fluorescent proteins are due to internal quadratic Stark effect. The journal of physical chemistry. B 113, 12860–12864, doi: 10.1021/jp907085p (2009).

Piatkevich, K. D. et al. Extended Stokes shift in fluorescent proteins: chromophore-protein interactions in a near-infrared TagRFP675 variant. Scientific reports 3, 1847, doi: 10.1038/srep01847 (2013).

Karniol, B., Wagner, J. R., Walker, J. M. & Vierstra, R. D. Phylogenetic analysis of the phytochrome superfamily reveals distinct microbial subfamilies of photoreceptors. The Biochemical journal 392, 103–116, doi: 10.1042/BJ20050826 (2005).

Giraud, E. & Vermeglio, A. Bacteriophytochromes in anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria. Photosynthesis research 97, 141–153, doi: 10.1007/s11120-008-9323-0 (2008).

Rockwell, N. C. & Lagarias, J. C. A brief history of phytochromes. Chemphyschem: a European journal of chemical physics and physical chemistry 11, 1172–1180, doi: 10.1002/cphc.200900894 (2010).

Fischer, A. J. & Lagarias, J. C. Harnessing phytochrome’s glowing potential. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101, 17334–17339, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407645101 (2004).

Shu, X. et al. Mammalian Expression of Infrared Fluorescent Proteins Engineered from a Bacterial Phytochrome. Science 324, 804–807, doi: 10.1126/science.1168683 (2009).

Auldridge, M. E., Satyshur, K. A., Anstrom, D. M. & Forest, K. T. Structure-guided Engineering Enhances a Phytochrome-based Infrared Fluorescent Protein. Journal of Biological Chemistry 287, 7000–7009, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.295121 (2012).

Filonov, G. S. et al. Bright and stable near-infrared fluorescent protein for in vivo imaging. Nature biotechnology 29, 757–761, doi: 10.1038/nbt.1918 (2011).

Shcherbakova, D. M. & Verkhusha, V. V. Near-infrared fluorescent proteins for multicolor in vivo imaging. Nature methods 10, 751–754, doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2521 (2013).

Shcherbakova, D. M., Baloban, M. & Verkhusha, V. V. Near-infrared fluorescent proteins engineered from bacterial phytochromes. Current opinion in chemical biology 27, 52–63, doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2015.06.005 (2015).

Shcherbakova, D. M. et al. Molecular Basis of Spectral Diversity in Near-Infrared Phytochrome-Based Fluorescent Proteins. Chem. Biol. 22, 1540–1551 (2015).

Tran, M. T. N. et al. In Vivo image Analysis Using iRFP Transgenic Mice. Experimental Animals 63, 311–319, doi: 10.1538/expanim.63.311 (2014).

Lamparter, T. et al. Biliverdin binds covalently to agrobacterium phytochrome Agp1 via its ring A vinyl side chain. The Journal of biological chemistry 278, 33786–33792, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305563200 (2003).

Wagner, J. R., Zhang, J., Brunzelle, J. S., Vierstra, R. D. & Forest, K. T. High resolution structure of Deinococcus bacteriophytochrome yields new insights into phytochrome architecture and evolution. The Journal of biological chemistry 282, 12298–12309, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611824200 (2007).

Rohmer, T. et al. Light-induced chromophore activity and signal transduction in phytochromes observed by C-13 and N-15 magic-angle spinning NMR. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105, 15229–15234, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805696105 (2008).

Yang, X., Kuk, J. & Moffat, K. Crystal structure of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteriophytochrome: Photoconversion and signal transduction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105, 14715–14720, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806718105 (2008).

Andel, F., Hasson, K. C., Gai, F., Anfinrud, P. A. & Mathies, R. A. Femtosecond time-resolved spectroscopy of the primary photochemistry of phytochrome. Biospectroscopy 3, 421–433, doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6343(1997)3:6<421::aid-bspy1>3.0.co;2-3 ( 1997).

Heyne, K. et al. Ultrafast dynamics of phytochrome from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis, reconstituted with phycocyanobilin and phycoerythrobilin. Biophysical journal 82, 1004–1016 (2002).

van Thor, J. J., Ronayne, K. L. & Towrie, M. Formation of the early photoproduct Lumi-R of cyanobacterial phytochrome Cph1 observed by ultrafast mid-infrared spectroscopy. Journal of the American Chemical Society 129, 126–132, doi: 10.1021/ja0660709 (2007).

Dasgupta, J., Frontiera, R. R., Taylor, K. C., Lagarias, J. C. & Mathies, R. A. Ultrafast excited-state isomerization in phytochrome revealed by femtosecond stimulated Raman spectroscopy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106, 1784–1789, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812056106 (2009).

Schumann, C., Gross, R., Michael, N., Lamparter, T. & Diller, R. Sub-picosecond mid-infrared spectroscopy of phytochrome Agp1 from Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Chemphyschem: a European journal of chemical physics and physical chemistry 8, 1657–1663, doi: 10.1002/cphc.200700210 (2007).

Toh, K. C., Stojkovic, E. A., van Stokkum, I. H., Moffat, K. & Kennis, J. T. Proton-transfer and hydrogen-bond interactions determine fluorescence quantum yield and photochemical efficiency of bacteriophytochrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107, 9170–9175, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911535107 (2010).

Mathes, T. et al. Femto- to Microsecond Photodynamics of an Unusual Bacteriophytochrome. Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 6, 239–243, doi: 10.1021/jz502408n (2015).

Muller, M. G., Lindner, I., Martin, I., Gartner, W. & Holzwarth, A. R. Femtosecond kinetics of photoconversion of the higher plant photoreceptor phytochrome carrying native and modified chromophores. Biophysical journal 94, 4370–4382, doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.091652 (2008).

Toh, K. C. et al. Primary Reactions of Bacteriophytochrome Observed with Ultrafast Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy. Journal of Physical Chemistry A 115, 3778–3786, doi: 10.1021/jp106891x (2011).

Borucki, B. et al. Light-induced proton release of phytochrome is coupled to the transient deprotonation of the tetrapyrrole chromophore. Journal of Biological Chemistry 280, 34358–34364, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505493200 (2005).

Krumholz, A., Shcherbakova, D. M., Xia, J., Wang, L. V. & Verkhusha, V. V. Multicontrast photoacoustic in vivo imaging using near-infrared fluorescent proteins. Scientific reports 4, 3939, doi: 10.1038/srep03939 (2014).

Rice, W. L., Shcherbakova, D. M., Verkhusha, V. V. & Kumar, A. T. In Vivo Tomographic Imaging of Deep-Seated Cancer Using Fluorescence Lifetime Contrast. Cancer research 75, 1236–1243, doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3001 (2015).

Berera, R., van Grondelle, R. & Kennis, J. T. Ultrafast transient absorption spectroscopy: principles and application to photosynthetic systems. Photosynthesis research 101, 105–118, doi: 10.1007/s11120-009-9454-y (2009).

Ravensbergen, J. et al. Unraveling the Carrier Dynamics of BiVO4: A Femtosecond to Microsecond Transient Absorption Study. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 118, 27793–27800, doi: 10.1021/jp509930s (2014).

Bonetti, C. et al. The role of key amino acids in the photoactivation pathway of the Synechocystis Slr1694 BLUF domain. Biochemistry 48, 11458–11469, doi: 10.1021/bi901196x (2009).

Gobets, B. et al. Excitation energy transfer in dimeric light harvesting complex I: A combined streak-camera/fluorescence upconversion study. Journal of Physical Chemistry B 105, 10132–10139, doi: Doi 10.1021/Jp011901c (2001).

van Stokkum, I. H. M. et al. The Primary Photophysics of the Avena sativa Phototropin 1 LOV2 Domain Observed with Time-resolved Emission Spectroscopy. Photochemistry and Photobiology 87, 534–541, doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2011.00903.x (2011).

Toh, K. C., Stojkovic, E. A., van Stokkum, I. H., Moffat, K. & Kennis, J. T. Fluorescence quantum yield and photochemistry of bacteriophytochrome constructs. Physical chemistry chemical physics: PCCP 13, 11985–11997, doi: 10.1039/c1cp00050k (2011).

Snellenburg, J. J., Laptenok, S. P., Seger, R., Mullen, K. M. & van Stokkum, I. H. M. Glotaran: A Java-Based Graphical User Interface for the R Package TIMP. J Stat Softw 49, 1–22 (2012).

van Stokkum, I. H., Larsen, D. S. & van Grondelle, R. Global and target analysis of time-resolved spectra. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1657, 82–104, doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.04.011 (2004).

Kennis, J. T. M. & Groot, M. L. Ultrafast spectroscopy of biological photoreceptors. Curr Opin Struc Biol 17, 623–630, doi: DOI 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.09.006 (2007).

Bellini, D. & Papiz, M. Z. Structure of a bacteriophytochrome and light-stimulated protomer swapping with a gene repressor. Structure 20, 1436–1446, doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.06.002 (2012).

Bellini, D. & Papiz, M. Z. Dimerization properties of the RpBphP2 chromophore-binding domain crystallized by homologue-directed mutagenesis. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography 68, 1058–1066, doi: 10.1107/S0907444912020537 (2012).

Yang, X., Stojkovic, E. A., Kuk, J. & Moffat, K. Crystal structure of the chromophore binding domain of an unusual bacteriophytochrome, RpBphP3, reveals residues that modulate photoconversion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104, 12571–12576, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701737104 (2007).

Stepanenko, O. V. et al. Allosteric effects of chromophore interaction with dimeric nearinfrared fluorescent proteins engineered from bacterial phytochromes. Scientific reports 6, 18750 (2016).

Zhu, J., Shcherbakova, D. M., Hontani, Y., Verkhusha, V. V. & Kennis, J. T. Ultrafast excited-state dynamics and fluorescence deactivation of near-infrared fluorescent proteins engineered from bacteriophytochromes. Scientific reports 5, 12840, doi: 10.1038/srep12840 (2015).

Marin, A. et al. Flow of Excitation Energy in the Cryptophyte Light-Harvesting Antenna Phycocyanin 645. Biophysical journal 101, 1004–1013, doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.07.012 (2011).

Nieder, J. B. et al. Pigment-Protein Interactions in Phytochromes Probed by Fluorescence Line Narrowing Spectroscopy. Journal of Physical Chemistry B 117, 14940–14950, doi: 10.1021/jp409110q (2013).

Essen, L.-O., Mailliet, J. & Hughes, J. The structure of a complete phytochrome sensory module in the Pr ground state. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105, 14709–14714, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806477105 (2008).

Burgie, E. S., Bussell, A. N., Walker, J. M., Dubiel, K. & Vierstra, R. D. Crystal structure of the photosensing module from a red/far-red light-absorbing plant phytochrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111, 10179–10184, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403096111 (2014).

Tang, K. et al. Terminal phycobilisome emitter, LCM: A light harvesting pigment with a phytochrome chromophore. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America in press, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1519177113 (2015).

Bhattacharya, S., Auldridge, M. E., Lehtivuori, H., Ihalainen, J. A. & Forest, K. T. Origins of Fluorescence in Evolved Bacteriophytochromes. Journal of Biological Chemistry 289, 32144–32152, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.589739 (2014).

Holzwarth, A. R., Bittersmann, E., Reuter, W. & Wehrmeyer, W. Studies on chromophore coupling in isolated phycobiliproteins. 3. Picosecond excited-state kinetics and time-resolved fluorescence-spectra of different allophycocyanins from mastigocladus-laminosus. Biophysical journal 57, 133–145 (1990).

Ying, L. M. & Xie, X. S. Fluorescence spectroscopy, exciton dynamics, and photochemistry of single allophycocyanin trimers. Journal of Physical Chemistry B 102, 10399–10409, doi: 10.1021/jp983227d (1998).

Marx, A. & Adir, N. Allophycocyanin and phycocyanin crystal structures reveal facets of phycobilisome assembly. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta-Bioenergetics 1827, 311–318, doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.11.006 (2013).

Stadnichuk, I. N. et al. Fluorescence quenching of the phycobilisome terminal emitter L-CM from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp PCC 6803 detected in vivo and in vitro. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B-Biology 125, 137–145, doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2013.05.014 (2013).

Kim, P. W., Rockwell, N. C., Martin, S. S., Lagarias, J. C. & Larsen, D. S. Dynamic inhomogeneity in the Photodynamics of Cyanobacterial Phytochrome Cph1. Biochemistry 53, 2818–2826, doi: 10.1021/bi500108s (2014).

Altoe, P. et al. Deciphering Intrinsic Deactivation/Isomerization Routes in a Phytochrome Chromophore Model. Journal of Physical Chemistry B 113, 15067–15073, doi: 10.1021/jp904669x (2009).

Escobar, F. V. et al. Structural Parameters Controlling the Fluorescence Properties of Phytochromes. Biochemistry 53, 20–29, doi: 10.1021/bi401287u (2014).

Zienicke, B. et al. Fluorescence of Phytochrome Adducts with Synthetic Locked Chromophores. Journal of Biological Chemistry 286, 1103–1113, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.155143 (2011).

Acknowledgements

Y.H., J.Z. and J.T.M.K. were supported by the Chemical Sciences Council of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) through a VICI grant and Middelgroot investment grant to J.T.M.K. D.M.S., M.B. and V.V.V. were supported by GM073913, GM105997 and GM108579 grants from the US National Institutes of Health and by ERC-2013-ADG-340233 grant from the EU FP7 program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.T.M.K. and V.V.V. designed the project. Y.H. and J.Z. carried out the ultrafast spectroscopic experiments. D.M.S. and M.B. developed the proteins and their mutants. D.M.S. and M.B. purified and characterized the proteins. Y.H., V.V.V. and J.T.M.K. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to discussions of the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Hontani, Y., Shcherbakova, D., Baloban, M. et al. Bright blue-shifted fluorescent proteins with Cys in the GAF domain engineered from bacterial phytochromes: fluorescence mechanisms and excited-state dynamics. Sci Rep 6, 37362 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37362

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37362

This article is cited by

-

Real-time observation of tetrapyrrole binding to an engineered bacterial phytochrome

Communications Chemistry (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.