Abstract

Iron availability affects swarming and biofilm formation in various bacterial species. However, how bacteria sense iron and coordinate swarming and biofilm formation remains unclear. Using Serratia marcescens as a model organism, we identify here a stage-specific iron-regulatory machinery comprising a two-component system (TCS) and the TCS-regulated iron chelator 2-isocyano-6,7-dihydroxycoumarin (ICDH-Coumarin) that directly senses and modulates environmental ferric iron (Fe3+) availability to determine swarming initiation and biofilm formation. We demonstrate that the two-component system RssA-RssB (RssAB) directly senses environmental ferric iron (Fe3+) and transcriptionally modulates biosynthesis of flagella and the iron chelator ICDH-Coumarin whose production requires the pvc cluster. Addition of Fe3+, or loss of ICDH-Coumarin due to pvc deletion results in prolonged RssAB signaling activation, leading to delayed swarming initiation and increased biofilm formation. We further show that ICDH-Coumarin is able to chelate Fe3+ to switch off RssAB signaling, triggering swarming initiation and biofilm reduction. Our findings reveal a novel cellular system that senses iron levels to regulate bacterial surface lifestyle.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Iron is essential for many cellular processes1. While low iron bioavailability is a limiting factor for cell survival in hostile environments, excess iron within the cell is toxic due in part to the formation of hydroxyl radicals through Fenton reactions2. Iron also serves as a stress signal that regulates microbial physiology, such as susceptibility to antibiotics3. Competition between the host and pathogens for limited iron resources may determine infections outcome4. Many homeostatic systems thus tightly control intracellular iron concentration in bacteria in order to allow adaptation to ever-changing environments5,6,7.

Swarming and biofilm formation are two typical multicellular behaviors of bacteria living on a surface8. Bacteria within biofilms embedded in an extracellular matrix undergo cellular differentiation and may acquire resistance to environmental stress and host immune responses9,10. On the other hand, swarming, which is observed in various bacterial species, represents a rapid, cell density-dependent, flagellum-driven movement of bacteria on a surface, and is closely associated with antibiotic resistance and production of virulence factors11,12,13,14,15. Swarming is characterized by a non-motile lag phase and an active migration phase associated with metabolic and morphological changes11,16,17. Several studies have identified regulatory systems that accelerate swarming migration velocity by increasing flagella and biosurfactant production18,19,20,21. However, the cellular mechanism underlying initiation of swarming and biofilm formation remains incompletely understood.

Swarming initiation is associated with changes in the expression of genes involved in the metabolism, acquisition and transport of iron in various bacterial species14,22,23. Iron limitation induces cell differentiation in swarming24, and disruption of the iron acquisition system affects swarming25. Additionally, iron chelation reduces biofilm formation, whereas iron overloading promotes biofilm formation26,27,28. Further identification of the sensor in response to environmental iron and downstream signaling may help us to understand the transition between swarming and biofilm formation.

Two-component systems (TCSs), typically composed of histidine sensor kinases and cognate response regulators, are among the most sophisticated signaling systems used by bacteria to sense and react to environmental stimuli. Control of phosphotransfer from membrane-bound histidine sensor kinases to response regulator in TCSs offers bacteria the ability to adapt to a wide range of environmental conditions29,30,31. We previously identified a TCS, called RssA-RssB (RssAB), whose activation is involved in coordinating the development of surface multicellularity as well as virulence in Serratia marcescens32,33,34,35,36. Here we show that RssA directly senses ferric iron (Fe3+) via its periplasmic region, and that this interaction leads to RssB phosphorylation. The Fe3+ chelator 2-isocyano-6,7-dihydroxycoumarin (ICDH-Coumarin), whose biosynthesis is under transcriptional control of RssAB signaling, is shown to fine-tune RssAB-modulated swarming initiation and biofilm formation by controlling extracellular Fe3+ availability. Our results show that extracellular iron sensing by a TCS regulates multicellular behaviors in bacteria.

Results

Fe3+ regulates swarming initiation and biofilm formation

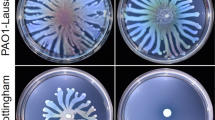

To examine whether iron regulates multicellular behavior, we used the wild-type (WT) S. marcescens CH-1 strain, which exhibits canonical swarming consisting of a non-motile lag phase and a motile migration phase35 on Luria-Bertani (LB) swarming plates. We observed that ferric iron (Fe3+) availability determines the timing of swarming initiation in the WT strain (Fig. 1a,b), without affecting swarming expansion rate (Supplementary Fig. 1). Fe3+ depletion by the Fe3+ chelator deferoxamine mesylate (DFO) reduced lag phase duration and induced early swarming initiation (Fig. 1a,b). On the other hand, Fe3+ supplementation (100 μM) prolonged the lag phase and delayed swarming initiation, which was restored by co-administration of Fe3+ and DFO (Fig. 1a,b). Of note, when growing on iron-limiting, defined minimal medium (DMM) swarming plates, no swarming lag phase was observed, while addition of Fe3+ dose-dependently extended the lag phase to 2 hrs in WT bacteria (Fig. 1c). These results suggest that Fe3+ may control swarming initiation.

Fe3+ controls swarming initiation and biofilm formation in S. marcescens through the TCS RssAB.

(a,b) Swarming pattern (a) and migration radius (b) of WT and ΔrssBA S. marcescens on LB swarming plates containing Fe3+ (100 μM) and/or DFO (0.3 mM). (c) Swarming migration radius of WT and ΔrssBA on DMM swarming plates containing Fe3+ at the indicated concentration (0–10 μM). The number in the lower right corner of each swarming plate image represents the duration of the lag phase in hours. Migration radius (mm) corresponds to mean ± SEM (n = 3). ND, not detected. (d) As mentioned in Methods, biofilm of WT and ΔrssBA S. marcescens in LB broth containing the indicated concentration of Fe3+ and/or DFO (0.3 mM) was quantified by monitoring absorbance at 630 nm. (e,f) In LB condition with or without Fe3+ (100 μM) and DFO (0.3 mM), swarming radius (e) and biofilm quantification (f) of ΔrssBA harboring the vector pACYC184 or the recombinant pACYC184 plasmid containing different constructs of RssB and RssA driven by their native promoters. RssBD51E and RssAH248A: constructs with point mutations at conserved phosphorylation sites; RssAΔPPD: RssA with deletion in periplamic domain (PPD, amino acids 32–163; RssAchimeric: a chimeric RssA whose periplasmic domain was replaced with the periplasmic domain of QseC. The results represent means ± SEM from three independent experiments (n = 3). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA. For Fig. 1d, *, ** and *** represent P < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, and 0.0001, respectively, compared to the untreated sample. # and ## represent P < 0.05 and 0.01, respectively, compared to the group treated with DFO but without Fe3+. For Fig. 1f, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 compared to LB group.

Addition of divalent cations such as Mg2+, Ca2+, Zn2+ and Co2+ produced no significant impact on swarming in S. marcescens (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Similarly to the effects of Fe3+, Fe2+ inhibited swarming and restored swarming induced by the metal-ion-chelator EDTA (Supplementary Fig. 2a). These effects were abrogated by the Fe2+ chelator 2,2′-dipyridyl (2,2′-DP) and the Fe3+ chelator DFO, while the effects of Fe3+ were abolished only by DFO (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Furthermore, Fe3+ and Fe2+-mediated repression of swarming was eliminated by addition of the reducing reagent sodium ascorbate37 (Supplementary Fig. 2c; ASC), suggesting that Fe3+ rather than Fe2+ is the main factor that delays swarming initiation.

The inverse relationship between swarming motility and biofilm formation8 led us to examine the effects of iron on biofilm formation. As expected, Fe3+ supplementation increased biofilm formation in a dose-dependent manner, and the effect of Fe3+ supplementation was inhibited by the addition of the Fe3+ chelator DFO (Fig. 1d). We concluded that extracellular Fe3+ concentration controls swarming initiation and biofilm formation in S. marcescens.

The TCS RssAB is required for Fe3+-mediated regulation of swarming initiation and biofilm formation in S. marcescens

We previously reported that the TCS RssAB is temporally activated during the swarming lag phase and delays swarming initiation in S. marcescens35. We thus investigated whether RssAB mediates the effect of Fe3+ on swarming initiation. Deletion of the rssBA locus in WT S. marcescens abolished the effects of both iron and iron chelators on swarming initiation, and the rssBA deletion mutant (ΔrssBA) constitutively displayed early swarming initiation on LB swarming plates, 1 hr earlier than the WT strain (Fig. 1a,b and Supplementary Fig. 2; ΔrssBA). In addition, the ability of Fe3+ to prolong the swarming lag phase on iron-limiting DMM swarming plates and to induce biofilm formation were not detected in the ΔrssAB strain (Fig. 1c,d; ΔrssBA). Episomal expression of a wild-type RssB-RssA construct in ΔrssBA bacteria complemented the iron responsiveness for both swarming (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 3) and biofilm formation (Fig. 1f). However, expression of RssB-RssA constructs harboring mutations at conserved phosphorylation sites, either at aspartate 51 (D51) for RssB or histidine 248 (H248) for RssA36, failed to rescue iron irresponsiveness in ΔrssBA bacteria, when either swarming (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 3) or biofilm formation was analyzed (Fig. 1f). These results demonstrate that RssAB signaling is responsible for the effects of Fe3+ on swarming initiation and biofilm formation in S. marcescens.

Fe3+ activates RssAB signaling during swarming and biofilm formation

To investigate whether environmental Fe3+ modulates RssAB, we monitored RssAB signaling in response to Fe3+ availability by examining the cytolocalization of enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-tagged RssB during swarming and biofilm formation (Fig. 2a)35. On LB swarming plates, dispersal of EGFP-RssB in the cytosol, which indicates activation of RssAB signaling (ON), was observed 2 hr in the swarming lag phase (Fig. 2b; LB-2 hr). During the surface migration phase of swarming, EGFP-RssB was detected at the cell membrane, which represents the resting state (OFF) of RssAB (Fig. 2b; LB-4, 6, 8 hr). While Fe3+ supplementation extended RssAB signaling activation to 4 hr (Fig. 2b; Fe3+), DFO-mediated Fe3+ depletion resulted in constitutive OFF signaling during the entire swarming period (Fig. 2b; DFO). Addition of both Fe3+ and DFO in LB swarming plates did not affect RssAB signaling state, indicating that the lag period was specifically extended by Fe3+ on LB swarming plates (Fig. 2b; Fe3+/DFO). In contrast to LB swarming plates, RssAB signaling was constitutively OFF on iron-limiting DMM swarming plates (Fig. 2c), where no lag phase was observed (Fig. 1c). Iron supplementation induced RssAB signaling and dose-dependently extended the duration of RssAB activation up to 2 hrs (Fig. 2c), which also prolonged the duration of the lag phase in swarming development (Fig. 1c).

Fe3+ availability regulates RssAB signaling status during swarming and biofilm development.

(a) Representative image of cytolocalization of EGFP-tagged RssB. Cytoplasmic and membrane location of EGFP-RssB indicates ON (activated) and OFF (inactivated) RssAB signaling status, respectively. Scale bar, 3 μm. (b) WT S. marcescens harboring the pEGFP-RssBA::Sm plasmid encoding EGFP-RssB and RssA was used to evaluate the state of RssAB signaling during swarming (2–8 hr). Swarming assays were performed on LB plates containing 0.1% arabinose with or without Fe3+ (100 μM) and DFO (0.3 mM). Cellular localization of EGFP-RssB was monitored to quantify the percentage of activated and inactivated RssAB signaling. (c) Quantification of RssAB signaling status during swarming progression (1–4 hr) on DMM swarming plates supplemented with Fe3+ at the indicated concentration (0–10 μM). (d) Quantification of RssAB signaling status during biofilm development (12–48 hr) in LB condition with or without Fe3+ (100 μM) and DFO (0.3 mM). Percentage of cell type is shown as mean from three independent experiments performed in triplicate. At least 200 cells were counted for each assay condition.

We previously showed35 that RssAB signaling is specifically activated during the early stage of biofilm formation (Fig. 2d; LB-12 hr) and is deactivated in mature biofilms (Fig. 2d; LB-24, 36 and 48 hr). Here, we found that, while addition of Fe3+ did not change the timing of RssAB activation (Fig. 2d; Fe3+), Fe3+ depletion by DFO abrogated activation of RssAB signaling (Fig. 2d; DFO), and this effect could be restored by Fe3+ supplementation (Fig. 2d; Fe3+/DFO). Together with the observation that RssAB signaling is required for Fe3+-mediated modulatory effects on swarming and biofilm formation (Fig. 1e,f and Supplementary Fig. 3), we conclude that Fe3+ controls RssAB signaling to regulate swarming and biofilm formation.

RssAB directly senses Fe3+ at the nanomolar level

To examine how Fe3+ affects RssAB signaling, we first studied RssAB signaling in response to Fe3+ addition in iron-limiting DMM broth, which allowed us to assess the status of RssAB signaling in real time. While RssAB signaling was constitutively OFF in DMM broth (Supplementary Fig. 4a), addition of Fe3+ immediately activated RssAB signaling for at least 60 min, and this effect was reverted by DFO (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Of note, replacement of Fe3+-treated bacterial culture broth with mock-treated culture broth deactivated RssAB signaling (Supplementary Fig. 4c), indicating that extracellular Fe3+ alters the state of RssAB signaling. We further demonstrated that Fe3+ at a concentration of 50 nM was sufficient to activate RssAB signaling (Supplementary Fig. 4d), consistent with the observation that 50 nM Fe3+ could prolong the duration of the lag phase on DMM swarming plates (Fig. 1c; WT).

To address whether Fe3+ triggers RssAB transphosphorylation, we performed liposome-based radiography phosphorylation assays by reconstituting purified His-tagged RssA into liposomes under various iron conditions. We found that as soon as 1 min after exposure to [γ32P]ATP, autophosphorylation of RssA occurred in the presence of Fe3+, followed by phosphotransfer to RssB (Fig. 3a). Fe3+-induced RssAB transphorylation was inhibited by co-treatment with the Fe3+ chelator DFO (Fig. 3b). While the presence of Fe2+ triggered RssA autophosphorylation, co-treatment with the reducing reagent ASC or the Fe3+ chelator DFO (but not the Fe2+ chelator 2,2′-DP) prevented RssA autophosphorylation (Fig. 3b). Importantly, Fe3+-induced phosphorelay was largely dependent on the conserved phosphorylation sites of RssA and RssB (Fig. 3b), consistent with our observation that only the expression of functional RssAB could restore the effects of Fe3+ on swarming migration (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 3), biofilm formation (Fig. 1f), and signaling activation (Supplementary Fig. 5) in ΔrssBA bacteria.

RssA binds Fe3+ through its periplasmic domain and transphosphorylates RssB.

(a) His-tagged RssA and RssB reconstituted in liposomes with or without Fe3+ was supplemented with [γ32P]ATP (50 μCi), collected at the indicated time points, and examined by radiography imaging. (b) Liposomes containing His-tagged RssA, RssB, nonphosphorylatable RssA or RssB were harvested 30 min after addition of [γ32P]ATP and examined by radiography imaging. (c) His-tagged RssA, RssAH248A (His248 mutated to Ala), RssAΔPPD (RssA with deletion in periplasmic domain), and RssAchimeric (a chimeric RssA whose periplasmic domain was replaced with the periplasmic domain of QseC) were reconstituted in liposomes containing 500 nM 55FeCl3. After incubation, disrupted liposomes passed through NTA column to remove unbound 55FeCl3. Iron-bound membrane proteins were eluted and subjected to radioactivity analysis of liquid scintillation counting (counts per min, CPM). (d) His-tagged periplasmic domain of RssA was incubated with 55FeCl3 and mock (distilled water), DFO (0.3 mM), ASC (0.3 mM), or 2,2′-DP (0.3 mM). Radioactivity was determined in the periplasmic domain eluted from Ni2+-NTA column. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA. For Fig. 1c, ****P-value < 0.0001, compared to RssA group. For Fig. 1d, *** and **** correspond to P-values < 0.001 and <0.0001, respectively, compared to mock group.

As the periplasmic region of sensor kinases is generally responsible for sensing environmental cues31, we prepared a plasmid construct harboring RssA without the periplasmic domain (RssAΔPPD) to test its function. Expression of RssA without the periplasmic domain (RssAΔPPD) failed to rescue the phenotypes of ΔrssBA to Fe3+ in swarming initiation (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 3), biofilm formation (Fig. 1f), and RssAB signaling (Supplementary Fig. 5). Using the 55FeCl3 binding assay, we observed that full-length RssA could bind to Fe3+, whereas RssAΔPPD could not (Fig. 3c,d). Additionally, free Fe3+, in the absence of DFO or ASC, could directly bind to the purified periplasmic domain of RssA, indicating that the periplamic domain of RssA is responsible for Fe3+ binding (Fig. 3d). To test the specificity of the RssA periplasmic domain to Fe3+, we constructed a chimeric RssA (RssAchimeric) in which the periplasmic region of RssA was replaced by the corresponding region of QseC, a sensor kinase not involved in iron sensing38. RssAchimeric did not interact with Fe3+ (Fig. 3c) and failed to restore the swarming lag period (Fig. 1e, Supplementary Fig. 3), biofilm formation (Fig. 1f), or Fe3+ responsiveness (Supplementary Fig. 5) in ΔrssBA bacteria. Collectively, these results indicate that Fe3+ directly and specifically binds to the periplasmic region of RssA, thereafter triggering RssAB signaling and regulating swarming initiation and biofilm formation.

Identification of the RssAB-regulated pvc cluster and its involvement in swarming and biofilm formation

To investigate whether RssAB signaling regulates extracellular Fe3+ availability, we performed an in vitro protein-DNA pull-down screening assay to identify genes involved in iron metabolism. We identified the promoter of the gene sma0021, annotated as pvcA, which is the first gene of the putative pvc cluster (Fig. 4a). The pvc cluster in S. marcescens is a homologue of the pvc operon in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which was previously found to be involved in biosynthesis of pseudoverdine, a metabolite that possesses Fe3+ chelation activity39. Clarke-Pearson et al. observed that the pvc operon is responsible for the production of 2-isocyano-6,7-dihydroxycoumarin (ICDH-Coumarin), named by the authors as paerucumarin40,41, which regulates biofilm formation in P. aeruginosa42. Using an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA), we confirmed direct binding of the pvcA promoter to phosphorylated GST-RssB-P, instead of unphosphorylated GST-RssBD51E or GST protein (Fig. 4b). We further showed that expression of pvcA in WT S. marcescens is down-regulated during the lag phase (2 hr), whereas it increases during the migration phase (4 hr) (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 7), in agreement with our previous observation that RssAB signaling is specifically activated in the lag phase to act as a transcriptional repressor (Fig. 2b). During swarming development, iron supplementation prolonged downregulation of the RssAB downstream genes flhDC34 and pvcA in an RssAB-dependent manner (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 7).

pvc cluster regulated by RssB is involved in regulating swarming and biofilm formation.

(a) Schematic map of the pvc cluster, RssB-P binding site, and pvc cluster deletion mutant. Red dash lines represent RssB-P binding sites (−349 to +38) of the pvcA promoter region. For construction of pvc cluster deletion mutants (Δpvc), genomic region between two asterisks (*) was replaced with Smr cassette. (b) EMSA was employed to confirm the interaction between phosphorylated RssB (RssB-P) and promoter region of pvcA (PpvcA). Digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled DNA fragments were incubated with purified GST, GST-RssBD51E or GST-RssB-P, followed by analysis by non-denaturing PAGE. Negative control (NC) was performed by incubating GST-RssB-P with the DNA sequence between M13F/M13R in the plasmid pBIISK. (c) During swarming progression (2–6 hr) with different iron conditions, relative expression of RssB downstream genes (flhDC and pvcA), normalized to 16S rRNA, in WT and ΔrssBA was respectively determined by qRT-PCR. (d,e) Swarming migration radius (d) and biofilm formation (e) of each strain of S. marcescens. Strain harboring pPvc encoding pvc cluster under pBAD promoter with 0.01% arabinose. The results shown represent means ± SEM from three independent experiments (n = 3). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA. For Fig. 4c, * and ** corresponding to P-value < 0.05 and <0.01 in comparison with LB group of each strain, respectively. For Fig. 4e, * corresponding to P-value < 0.05 compared to WT.

To understand the function of the pvc cluster in multicellular behavior, we constructed a whole pvc cluster deletion mutant (Fig. 4a). Compared to the WT strain, the pvc cluster deletion mutant (Δpvc) showed delayed swarming initiation (Fig. 4d) and increased biofilm formation (Fig. 4e), with both processes being reversed by episomal expression of the pvc cluster (Fig. 4d,e; Δpvc/pPvc). In contrast, the rssBA and pvc cluster double-deletion mutant exhibited early swarming initiation and reduced biofilm formation as observed in ΔrssBA (Fig. 4d,e; ΔrssBA-pvc). These data suggest that a metabolite produced by the pvc cluster may inhibit RssAB activation.

The pvc cluster is responsible for ICDH-Coumarin production in S. marcescens

To determine whether the pvc cluster in S. marcescens is responsible for the production of a molecule similar to pseudoverdine or paerucumarin identified in P. aeruginosa, we used liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Fig. 8a) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (Supplementary Fig. 8b) to identify the compounds that were enriched in S. marcescens over-expressing the pvc cluster (pPvc). A compound corresponding to 2-isocyano-6,7-dihydroxycoumarin (ICDH-Coumarin) (with the same structure as paerucumarin) was identified (Fig. 5a; highlighted as *; Supplementary Fig. 8)40; the ICDH-Coumarin compound was not observed in Δpvc bacteria expressing the vector only. The purified ICDH-Coumarin harbored Fe3+ chelation activity similar to that of DFO but to a lesser extent (Fig. 5b). ICDH-Coumarin prevented direct binding of Fe3+ to the periplasmic domain of RssA (Fig. 5c). These findings demonstrate that the pvc cluster is implicated in ICDH-Coumarin production and that ICDH-Coumarin can chelate Fe3+ to abolish RssA-Fe3+ binding.

ICDH-Coumarin produced from pvc gene cluster chelates Fe3+ and blocks iron binding to RssA.

(a) LC-MS chromatogram of ethyl acetate extracts from WT, Δpvc, ΔrssBA, and ΔrssBA-pvc bacteria harboring pBAD33 (vector) or pPvc encoding pvc cluster under DMM broth with arabinose (0.3%). *Indicates the peak and structure of ICDH-Coumarin as determined by NMR. (b) Fe3+ chelation activity of DFO, ICDH-Coumarin, and 2,2′-DP at the indicated concentration. (c) His-tagged periplasmic domain of RssA was incubated with 55FeCl3 and distilled water (mock), DFO (0.3 mM), ICDH-Coumarin (0.3 mM), or 2,2′-DP (0.3 mM). Radioactivity was determined from the eluted periplasmic domain. One-way ANOVA with *** corresponding to P-value < 0.001 compared to mock group.

ICDH-Coumarin controls RssAB signaling and multicellular behaviors by modulating extracellular Fe3+ availability

We aimed to determine whether ICDH-Coumarin might alter extracellular iron availability and subsequently regulate RssAB signaling as well as multicellular behaviors. While addition of 30 μM ICDH-Coumarin restored the delayed swarming migration phenotype of Δpvc and induced early swarming migration in WT S. marcescens similar to DFO (Fig. 6a; 30 μM), supplementation of 300 μM ICDH-Coumarin induced early swarming migration even in Δpvc bacteria (Fig. 6a; 300 μM ICDH-Coumarin for Δpvc). Moreover, early swarming initiation induced by ICDH-Coumarin was accompanied by deactivation of RssAB signaling in both WT and Δpvc bacteria (Fig. 6b). The effects of ICDH-Coumarin supplementation on swarming initiation and RssAB signaling could also be observed by overexpression of the pvc cluster (Supplementary Fig. 9a,b). Conversely, regulation of swarming initiation by ICDH-Coumarin or pvc overexpression was completely abolished in the absence of rssBA (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 9a,b). On the other hand, addition of ICDH-Coumarin induced early swarming initiation (Fig. 6c) and impaired biofilm formation similar to DFO treatment (Fig. 6d), and these effects could be restored by addtion of Fe3+. Taken together, our results demonstrate that ICDH-Coumarin is produced by the RssAB-regulated pvc cluster and that it regulates swarming and biofilm formation by altering extracellular Fe3+ availability and RssAB signaling.

ICDH-Coumarin induces swarming initiation and represses biofilm formation by modulating extracellular Fe3+ availability and RssAB signaling.

(a) Migration radius of WT, ΔrssBA, Δpvc, and ΔrssBA-pvc strains on LB swarming plates supplemented with ICDH-Coumarin (0–300 μM). (b) Quantified RssAB signaling of WT and Δpvc carrying pEGFP-RssBA::Gm during swarming progression (2–8 hr) on LB swarming plates containing arabinose (0.1%) and ICDH-Coumarin (0–300 μM) is shown. (c) Migration radius of WT and Δpvc on LB swarming plates supplemented with or without Fe3+ (100 μM) and ICDH-Coumarin (300 μM). (d) Biofilm of WT and Δpvc in LB condition supplemented with or without Fe3+ (100 μM) and ICDH-Coumarin (300 μM) was determined by monitoring absorbance at 630 nm. The results shown represent means ± SEM from three independent experiments (n = 3). One-way ANOVA with * and ** represent P values < 0.05 and <0.01 compared to LB group; # represents P-value < 0.05 compared to ICDH-Coumarin group.

Discussion

Swarming and biofilm formation are two opposite but inter-related bacterial behaviors that are also among the most ancient features of living cells10. Here, we demonstrate that environmental Fe3+ availability controls the transition between swarming initiation and biofilm formation through an RssAB signaling system in S. marcescens. We further determine that the RssAB-modulated pvc cluster produces the Fe3+ chelator ICDH-Coumarin to regulate extracellular iron availability and RssAB signaling (Fig. 7). Our results show that RssAB signaling is off at low Fe3+ concentrations, during which the pvc cluster is expressed to produce ICDH-Coumarin and chelate extracellular Fe3+ (Fig. 7a). In an environment in which Fe3+ is abundant, Fe3+ directly binds to RssA, leading to RssA autophosphorylation and RssAB transphosphorylation, resulting in downregulated expression of the pvc cluster, reduced ICDH-Coumarin production, and decreased extracellular Fe3+ chelation (Fig. 7b).

Proposed model for the control of swarming and biofilm formation by the RssAB-ICDH-Coumarin-iron pathway.

(a) Low extracellular Fe3+ deactivates RssAB signaling and relieves transcription of the pvc cluster and flhDC, which encodes the master regulator of flagellum biosynthesis This in turn increases flagellum and production of ICDH-Coumarin which subsequently chelates Fe3+ to maintain low availability of free Fe3+. These processes induce swarming and repress biofilm formation. (b) High extracellular Fe3+ activates RssAB signaling, leading to phosphorylation of RssB, repression of pvc cluster and flhDC transcription, and reduced ICDH-Coumarin and flagellum production. High Fe3+ availability sustains activation of RssAB signaling. These processes lead to biofilm formation and inhibit swarming migration by restraining bacteria in the swarming lag phase.

Bacteria utilize a broad array of strategies to control the timing and duration of TCS signaling events in order to precisely control cellular processes based on extracellular signals43. In the context of the RssAB-ICDH-Coumarin-iron regulation circuit (Fig. 7), S. marcescens actively regulates extracellular iron availability through RssAB-modulated production of ICDH-Coumarin. Upon sensing high extracellular Fe3+ concentration, the decrease in ICDH-Coumarin production by transcriptional repression of phosphorylated RssB in turn maintains active RssAB signaling, which restricts bacterial migration and promotes biofilm formation. Of note, we previously reported that RssAB activation suppresses bacterial swarming motility by repressing flhDC expression34, whereas overexpression of flhDC reduces biofilm formation33. Together with the results presented in this study that functional RssAB signaling is required for iron to downregulate flhDC expression, restrict swarming migration and promote biofilm formation, we highlight the pivotal role of iron-RssAB-FlhDC signaling in regulation of swarming and biofilm formation (Fig. 7). These results also indicate that tight regulation of flagellum production by RssAB-ICDH-Coumarin-iron is crucial for the development of multicellular behavior in S. marcescens.

Based on LC-MS and NMR analyses, ICDH-Coumarin secreted by S. marcescens (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 8) and identified in this study has the same molecular structure (2-isocyano-6,7-dihydroxycoumarin) as paerucumarin in P. aeruginosa40,41. While ICDH-Coumarin (paerucumarin) enhances biofilm formation in P. aeruginosa by upregulating the fimbrial synthesis pathway42, we demonstrated here that ICDH-Coumarin reduces biofilm formation in S. marcescens. The different roles of this iron-chelating molecule in controlling multicellular behavior in P. aeruginosa and S. marcescens indicate that different cellular machineries may have evolved in response to a specific extracellular signal. Conservation of the pvc cluster across various bacterial species40 and the function of ICDH-Coumarin in regulating bacterial behavior suggest that ICDH-Coumarin may be involved in interspecies communication.

Competition for iron between microbes in the environment usually involves the coordination of various bacterial activities, including oxidative stress response, antibiotics resistance, virulence and multicellular behavior44,45,46,47. Previously, the TCS PmrA-PmrB was found to be vital for survival of Salmonella enterica under high iron stress through direct sensing of extracellular iron29. It was further shown that high iron resistance is mediated by lipopolysaccharide modifications48. Here we show that RssAB participates in a sophisticated control system to regulate multicellular behavior without conferring iron resistance since rssBA deletion does not affect growth in either iron-abundant or iron-limiting conditions. The presence of multiple sensing systems in deciphering iron availability may provide flexibility for bacteria to thrive under changing environments. In summary, this study identifies a cellular mechanism underlying the transition between bacterial motility and static colonization, which are associated with acute and chronic infection, respectively, in response to extracellular iron availability. Our findings should prove helpful to understand the factors that determine bacterial acute or chronic infection as well as for the development of novel treatments against pathogenic bacteria.

Methods

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

S. marcescens strains were derived from S. marcescens CH-1 (WT). Bacteria were routinely cultured with agitation in LB broth (BD DifcoTM, U.S.A.) at 30 °C or 37 °C. M9 salt (BD DifcoTM, U.S.A.) solution49 was used to make defined minimal medium (DMM) containing 1× M9 salts, 2 mM magnesium sulfate, 100 μM calcium chloride, 0.8% glycerol, and 0.2% casamino acid. DMM was used as iron-limiting medium. When strains harboring pBAD series of plasmids were used, arabinose was added into the medium at the indicated concentrations. Bacterial strains and plasmids are summarized in Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Methods.

Swarming assay

Swarming assay was performed on swarming plates in the presence or absence of metal ions, metal chelators, ICDH-Coumarin, or reducing agent at the indicated concentrations. S. marcescens strains were cultured on swarming plates (0.8% Eiken agar, EIKEN Chemical, Japan) consisting of LB (BD Difco™, U.S.A.) or DMM medium. The swarming lag phase was defined as the static period prior to migration.

Biofilm assay

Biofilm formation assay was performed based on a previous study35. Briefly, overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 in LB medium containing 1% (w/v) sucrose in Petri dish with sterile glass coverslips for incubation at 30 °C with agitation at 50 rpm. For iron modification, 10-hr-old biofilm cultures were supplemented with ferric chloride (Sigma-Aldrich, U.S.A.), DFO (final concentration: 0.3 mM) (Sigma-Aldrich, U.S.A.) and/or ICDH-Coumarin at the indicated concentration. Biofilm mass was quantified on glass coverslips at maturation stage (24 hr) using crystal-violet staining and spectrophotometery detection at 630 nm (OD630). Results are shown as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM) based on three independent experiments.

Imaging and quantification of RssAB signaling using fluorescence microscopy

RssAB signaling was determined by localization of EGFP-tagged RssB as before35. Briefly, EGFP-RssB and RssA either from pEGFP-RssBA::Sm35 or pEGFP-RssBA::Gm (Supplementary Table 2) were co-expressed under the PBAD promoter control and induced by 0.1% arabinose. At the indicated time points of swarming and biofilm assay, cells were harvested to determine the percentage of population showing EGFP-RssB localized at the cell membrane (OFF) or in the cytoplasm (ON). Fluorescence microscopy was conducted with a Leica DM2500 microscope under a Leica I3 filter set and observed at 100x using an oil immersion objective. Images were taken with a SPOT RT3 CCD camera (Diagnostic Instruments, U.S.A) and adjusted using the SPOT Advanced software (Diagnostic Instruments, U.S.A.). At least 200 cells were counted for each assay condition. Results are shown as the average of percentage of two populations from three independent experiments.

Liposome-based phosphorelay of RssAB signaling cascade

Liposome-based resconstitution38 of purified RssA and RssB, either untreated or supplemented with the indicated concentration of iron, reducing agent, or iron chelators, was subjected to radioisotope [γ32P]ATP (PerkinElmer, U.S.A.) phosphorelay.

Iron binding assay

Purified His-tagged RssA periplasmic domain was incubated with 500 nM 55FeCl3 and 0.3 mM of DFO, 2,2′-DP (Sigma-Aldrich, U.S.A.), ASC (Sigma-Aldrich, U.S.A.), or ICDH-Coumarin. After passing through Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) affinity chromatography (GE Healthcare Lifesciences, U.S.A.), the protein was eluted and subjected to liquid scintillation counting to measure radioactivity of 55Fe, expressed as counts per min (CPM × 103). For His-tagged membrane proteins, including RssA, RssAH248A, RssAΔPPD, and RssAchimeric, each of them was reconstituted in liposome containing 500 nM 55FeCl3, followed by removal of unbound 55FeCl3 and elution of iron using NTA column. The resulting eluents were subjected to liquid scintillation counting.

In vitro protein-DNA pull-down assay

The assay used was modified from Dietz et al.50. Briefly, WT S. marcescens chromosomal DNA was digested by Sau3AI and resuspended in 1 ml of interaction buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl) containing 25 mM acetyl-phosphate, 5 mM EDTA and 10 μg/ml BSA. GST-RssB was phosphorylated by 50 mM acetyl-phosphate at 37 °C for 1 hr, prior to addition into the mixture containing WT S. marcescens chromosomal DNA fragments. After incubation at room temperature for 20 min, 30 μL glutathione sepharose-4B beads equilibrated with PBS were added into the mixture. The whole mixture was placed at 4 °C with constant shaking for 30 min. The beads bound to GST-RssB with binding DNA fragments were recovered by low-speed centrifugation. After three washing steps with 500 μl of interaction buffer, the DNA was purified by phenol extraction and precipitated with isopropanol. Following precipitation, the bound DNA was analyzed on 2% agarose gel, and cloned into the BamHI site of pBluscriptIISK. The GenBank accession number of pvcABC is KC291199.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

Promoter region of pvcA (PpvcA) and rssB (PrssB) was cloned into the BamHI site on pBluescript II SK+ to generate pBSK-PpvcA and pBSK-PrssB, respectively. DNA fragments for electrophoretic mobility shift assay were amplified by PCR using the M13F-DIG/M13R primer pairs using pBSK-PpvcA, pBSK-PrssB or pBluescript II SK+ (negative control, NC) as a template. GST, GST-RssB and GST-RssBD51E protein purification, and GST-RssB phosphorylation using acetyl-phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich, U.S.A.) were performed as described in our previous report35. Phosphorylated GST-RssB or GST-RssBD51E was diluted in binding reaction buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl) before binding assay. The binding reaction was performed in binding reaction buffer, comprising the protein as indicated and 0.5 ng DIG labeled DNA fragments supplemented with 30 μg/ml poly (dI-dC) and 1 μg/μl bovine serum albumin. The reaction mixtures were incubated for 30 min at room temperature before being loaded onto 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels containing 0.5× TBE buffer. Electrophoresis was performed at 100 V for 1–4 hr. The DNA-protein complexes were then electroblotted onto a positively charged Hybond-N nylon membrane (Amersham, U.S.A.) and detected using alkaline phosphatase conjugated anti-DIG antibodies (Roche Life Science, U.S.A.). CSPD (Roche Life Science, U.S.A.) was used for substrate as described by the manufacturer. Membranes were exposed to X-ray film at room temperature for 2 to 30 min.

Evaluation of gene expression

Total bacterial RNA was extracted using a Trizol kit (Invitrogen). After verifying the quality (A260/A280 = 1.8–2.0) and concentration, 200 ng of RNA was subjected to reverse-transcription into cDNA with a SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System kit (Invitrogen, U.S.A.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. 5 ng of cDNA was then applied to KAPA SYBR FAST Master Mix (2X) qPCR kit (Kapa Biosystems, South Africa). Expression level of target genes tested was verified by real-time quantitative PCR detection system (Roche LightCycler 480, U.S.A.). Melting curves and Ct values were analyzed using the LightCycler® 480 SW version 1.5 (Roche, U.S.A.). The data were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCT method51. Relative expression of target genes was normalized to 16S rRNA (Fig. 4c) or rpoD (Supplementary Fig. 7). The procedures used for qRT-PCR followed the MIQE guidelines52. The primers used in this study are summarized in Supplementary Table 2.

Detection and purification of 2-isocyano-6,7-dihydroxycoumarin (ICDH-Coumarin)

ICDH-Coumarin was detected and purified according to the procedures described previously40 with minor modifications. Briefly, S. marcescens harboring pBAD33 (vector) or pPvc containing the full-length pvc cluster was grown in DMM broth with arabinose (0.3%) at 30 °C for 8 hr. Ethyl acetate extraction of each supernatant was collected by mixing the supernatant (50 ml) with ethyl acetate containing 2% methanol (100 ml). ICDH-Coumarin from ethyl acetate extract was purified using silica gel flash columns (CHCl3:MeOH at 9:1 followed by CH2Cl2:MeOH:AcOH at 93:7:0.1). The resultant filtrate was applied to LC-MS (negative-ion electrospray ionization, Waters, U.S.A.) and NMR (Bruker Avance III-HD 600 MHz NMR Spectrometer, U.S.A.). For LC-MS, 25 μl of a 10-fold dilution of the resultant filtrate was subjected to LC-MS (XBridge C18 column of 5 μm, 4.6×100 mm). UV absorbance from 210 to 600 nm was measured on a Waters Photodiode Array Detector. Spectrum of ESI-LC-MS was plotted as intensity (y axis) against m/z (Da). The m/z of ICDH-Coumarin is 204.03023. For NMR conditions, vacuum-dried samples were dissolved in 600 μl of methanol-d4/dichloromethane-d2 (CD3OD/CD2Cl2), followed by vortexing (1 min), sonication (5 min), and vortexing (1 min). After centrifugation (13,200 rpm), the supernatant was transferred to a NMR tube (5 mm). NMR spectra were recorded at 600 MHz on a Bruker Avance III spectrometer. 1H-NMR (CD3OD/CD2Cl2) proton spectrum of ICDH-Coumarin was ploted as intensity (y axis) against chemical shift (x axis) (δ, ppm). The identified chemical shift of ICDH-Coumarin includes 9.50 (s, 1H), 8.39 (s, 1H), 7.67 (s, 1H), 6.87 (s, 1H), and 6.87 (s, 1H).

Determination of Fe3+ chelation activity

Fe3+ chelation activity was determined using the chrome azurol sulfonate (CAS, Sigma-Aldrich, U.S.A.) solution assay53 with minor modifications. Briefly, 100 μl of ICDH-Coumarin (in ethyl acetate), DFO (in water), and 2,2′-DP (in dimethyl sulfoxide) at the indicative concentration (μm) or the respective solvent (as blank) were mixed with 100 μl of CAS solution and 10 μl of 0.2 M 5′-sulfosalicylic acid, prior to incubation at room temperature for 15 min. Absorbance at a wavelength of 630 nm for sample (As) and blank (Ab) was determined using a spectrophotometer. Fe3+ chelation activity was expressed as the ratio of (Ab − As)/Ab.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as means ± SEM from three independent experiments (n = 3). Statistical difference was calculated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) by comparing the groups indicated. P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Lin, C. S. et al. An iron detection system determines bacterial swarming initiation and biofilm formation. Sci. Rep. 6, 36747; doi: 10.1038/srep36747 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Andrews, S. C., Robinson, A. K. & Rodriguez-Quinones, F. Bacterial iron homeostasis. FEMS Microbiol Rev 27, 215–237 (2003).

Touati, D. Iron and oxidative stress in bacteria. Arch Biochem Biophys 373, 1–6 (2000).

Yeom, J., Imlay, J. A. & Park, W. Iron homeostasis affects antibiotic-mediated cell death in Pseudomonas species. J Biol Chem 285, 22689–22695 (2010).

Marx, J. J. Iron and infection: competition between host and microbes for a precious element. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 15, 411–426 (2002).

Braun, V. & Hantke, K. Recent insights into iron import by bacteria. Curr Opin Chem Biol 15, 328–334 (2011).

Cornelis, P., Wei, Q., Andrews, S. C. & Vinckx, T. Iron homeostasis and management of oxidative stress response in bacteria. Metallomics 3, 540–549 (2011).

Troxell, B. & Hassan, H. M. Transcriptional regulation by Ferric Uptake Regulator (Fur) in pathogenic bacteria. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 3, 59 (2013).

Verstraeten, N. et al. Living on a surface: swarming and biofilm formation. Trends Microbiol 16, 496–506 (2008).

Lewis, K. Multidrug tolerance of biofilms and persister cells. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 322, 107–131 (2008).

Hall-Stoodley, L., Costerton, J. W. & Stoodley, P. Bacterial biofilms: from the natural environment to infectious diseases. Nat Rev Microbiol 2, 95–108 (2004).

Kearns, D. B. & Losick, R. Swarming motility in undomesticated Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol 49, 581–590 (2003).

Butler, M. T., Wang, Q. & Harshey, R. M. Cell density and mobility protect swarming bacteria against antibiotics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107, 3776–3781 (2010).

Lai, S., Tremblay, J. & Deziel, E. Swarming motility: a multicellular behaviour conferring antimicrobial resistance. Environ Microbiol 11, 126–136 (2009).

Overhage, J., Bains, M., Brazas, M. D. & Hancock, R. E. Swarming of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a complex adaptation leading to increased production of virulence factors and antibiotic resistance. J Bacteriol 190, 2671–2679 (2008).

Partridge, J. D. & Harshey, R. M. Swarming: flexible roaming plans. J Bacteriol 195, 909–918 (2013).

Harshey, R. M. Bacterial motility on a surface: many ways to a common goal. Annu Rev Microbiol 57, 249–273 (2003).

Kim, W. & Surette, M. G. Metabolic differentiation in actively swarming Salmonella. Mol Microbiol 54, 702–714 (2004).

Givskov, M. et al. Two separate regulatory systems participate in control of swarming motility of Serratia liquefaciens MG1. J Bacteriol 180, 742–745 (1998).

Rather, P. N. Swarmer cell differentiation in Proteus mirabilis. Environ Microbiol 7, 1065–1073 (2005).

Van Houdt, R., Givskov, M. & Michiels, C. W. Quorum sensing in Serratia. FEMS Microbiol Rev 31, 407–424 (2007).

Mukherjee, S. et al. Adaptor-mediated Lon proteolysis restricts Bacillus subtilis hyperflagellation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112, 250–255 (2015).

Inoue, T. et al. Genome-wide screening of genes required for swarming motility in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol 189, 950–957 (2007).

Wang, Q., Frye, J. G., McClelland, M. & Harshey, R. M. Gene expression patterns during swarming in Salmonella typhimurium: genes specific to surface growth and putative new motility and pathogenicity genes. Mol Microbiol 52, 169–187 (2004).

McCarter, L. & Silverman, M. Iron regulation of swarmer cell differentiation of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J Bacteriol 171, 731–736 (1989).

Matilla, M. A. et al. Temperature and pyoverdine-mediated iron acquisition control surface motility of Pseudomonas putida. Environ Microbiol 9, 1842–1850 (2007).

Wu, Y. & Outten, F. W. IscR controls iron-dependent biofilm formation in Escherichia coli by regulating type I fimbria expression. J Bacteriol 191, 1248–1257 (2009).

Singh, P. K., Parsek, M. R., Greenberg, E. P. & Welsh, M. J. A component of innate immunity prevents bacterial biofilm development. Nature 417, 552–555 (2002).

Banin, E., Vasil, M. L. & Greenberg, E. P. Iron and Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102, 11076–11081 (2005).

Wosten, M. M., Kox, L. F., Chamnongpol, S., Soncini, F. C. & Groisman, E. A. A signal transduction system that responds to extracellular iron. Cell 103, 113–125 (2000).

Laub, M. T. & Goulian, M. Specificity in two-component signal transduction pathways. Annu Rev Genet 41, 121–145 (2007).

Krell, T. et al. Bacterial sensor kinases: diversity in the recognition of environmental signals. Annu Rev Microbiol 64, 539–559 (2010).

Lai, H. C. et al. The RssAB two-component signal transduction system in Serratia marcescens regulates swarming motility and cell envelope architecture in response to exogenous saturated fatty acids. J Bacteriol 187, 3407–3414 (2005).

Lin, C. S. et al. RssAB-FlhDC-ShlBA as a major pathogenesis pathway in Serratia marcescens. Infect Immun 78, 4870–4881 (2010).

Soo, P. C. et al. Regulation of swarming motility and flhDCSm expression by RssAB signaling in Serratia marcescens. J Bacteriol 190, 2496–2504 (2008).

Tsai, Y. H. et al. RssAB signaling coordinates early development of surface multicellularity in Serratia marcescens. PLoS One 6, e24154 (2011).

Wei, J. R. et al. Biochemical characterization of RssA-RssB, a two-component signal transduction system regulating swarming behavior in Serratia marcescens. J Bacteriol 187, 5683–5690 (2005).

Wyckoff, E. E., Mey, A. R., Leimbach, A., Fisher, C. F. & Payne, S. M. Characterization of ferric and ferrous iron transport systems in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol 188, 6515–6523 (2006).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001).

Clarke, M. B., Hughes, D. T., Zhu, C., Boedeker, E. C. & Sperandio, V. The QseC sensor kinase: a bacterial adrenergic receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103, 10420–10425 (2006).

Stintzi, A. et al. Novel pyoverdine biosynthesis gene(s) of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO. Microbiology 142 (Pt 5), 1181–1190 (1996).

Clarke-Pearson, M. F. & Brady, S. F. Paerucumarin, a new metabolite produced by the pvc gene cluster from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 190, 6927–6930 (2008).

Drake, E. J. & Gulick, A. M. Three-dimensional structures of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PvcA and PvcB, two proteins involved in the synthesis of 2-isocyano-6,7-dihydroxycoumarin. J Mol Biol 384, 193–205 (2008).

Qaisar, U. et al. The pvc operon regulates the expression of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa fimbrial chaperone/usher pathway (cup) genes. PLoS One 8, e62735 (2013).

Rowland, M. A. & Deeds, E. J. Crosstalk and the evolution of specificity in two-component signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111, 5550–5555 (2014).

Garcia, C. A., Alcaraz, E. S., Franco, M. A. & Passerini de Rossi, B. N. Iron is a signal for Stenotrophomonas maltophilia biofilm formation, oxidative stress response, OMPs expression, and virulence. Front Microbiol 6, 926 (2015).

Mehi, O. et al. Perturbation of iron homeostasis promotes the evolution of antibiotic resistance. Mol Biol Evol 31, 2793–2804 (2014).

Skaar, E. P. The battle for iron between bacterial pathogens and their vertebrate hosts. PLoS Pathog 6, e1000949 (2010).

Visaggio, D. et al. Cell aggregation promotes pyoverdine-dependent iron uptake and virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front Microbiol 6, 902 (2015).

Nishino, K. et al. Identification of the lipopolysaccharide modifications controlled by the Salmonella PmrA/PmrB system mediating resistance to Fe(III) and Al(III). Mol Microbiol 61, 645–654 (2006).

Sambrook, J., Maniatis, T. & Fritsch, E. F. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, 1989).

Dietz, P., Gerlach, G. & Beier, D. Identification of target genes regulated by the two-component system HP166-HP165 of Helicobacter pylori. J Bacteriol 184, 350–362 (2002).

Bustin, S. A. et al. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin Chem 55, 611–622 (2009).

Schwyn, B. & Neilands, J. B. Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Anal Biochem 160, 47–56 (1987).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (MOST 103-2320-B-182-027-MY3; MOST103-2321-B-182-014-MY3) and Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (CMRPD1C0783; CMRPD1E0071-3; BMRPA04).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.S.L., Y.H.T., H.C.L. and J.D.Y. designed all experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. C.S.L. and Y.H.T. conducted most of the experiments. C.S.L., Y.H.T., C.J.C. and S.F.T. contributed to the generation of mutants and recombinant plasmids and protein purification. C.S.L., Y.H.T. and T.R.W. performed EMSA and gene expression analysis. C.S.L., Y.H.T., C.C.L. and T.S.W. performed iron binding assays, signaling observations, and isotope experiments. J.J.L., J.T.H., J.M., D.M.O. and J.D.Y. helped to prepare the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, CS., Tsai, YH., Chang, CJ. et al. An iron detection system determines bacterial swarming initiation and biofilm formation. Sci Rep 6, 36747 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36747

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36747

This article is cited by

-

Repurposing of antidiabetics as Serratia marcescens virulence inhibitors

Brazilian Journal of Microbiology (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.