Abstract

Anthropogenic 129I as a long-lived radioisotope of iodine has been considered as an ideal oceanographic tracer due to its high residence time and conservative property in the ocean. Surface water samples collected from the East China Sea (ECS) in August 2013 were analyzed for 129I, 127I and their inorganic chemical species in the first time. The measured 129I/127I ratio is 1–3 orders of magnitude higher than the pre-nuclear level, indicating its dominantly anthropogenic sources. Relatively high 129I levels were observed in the Yangtze River and its estuary, as well as in the southern Yellow Sea, and 129I level in seawater declines towards the ECS shelf. In the open sea, 129I and 127I in surface water exists mainly as iodate, while in Yangtze River estuary and some locations, iodide is dominated. The results indicate that the Fukushima nuclear accident has no detectable effects in the ECS until August 2013. The obtained results are used for investigation of interaction of various water masses and water circulation in the ECS, as well as the marine environment in this region. Meanwhile this work provides essential data for evaluation of the possible influence of the increasing NPPs along the coast of the ECS in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

129I (15.7 Ma) is naturally produced by cosmic ray induced spallation of xenon in the atmosphere and fission of uranium on the earth with a 129I/127I atomic ratio of 1.5 × 10−12 in the pre-nuclear seawater samples1. While large amount of 129I has been released to the environment by human nuclear activities, among them atmospheric nuclear weapons testing (NWT) in 1945–1980 and spent nuclear fuel reprocessing are two major contributions of 129I in the environment2. The large and well documented 129I releases and the high residence time of iodine in the ocean make 129I an ideal oceanographic tracer, a number of studies have been carried out in the North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans using 129I and its species for water circulation and marine environment investigation3,4,5. A few investigation of 129I in the Pacific Ocean were reported6,7,8. However, investigation of 129I in the East China Sea (ECS) and the Yellow Sea (YS) is rare. The Fukushima nuclear accident happened in March 2011 has released a large amount of radioactive substance to the atmosphere and seas. The measurement of 129I in the Fukushima offshore seawater has shown a significant Fukushima derived 129I signals9,10. However, there was no report showing the Fukushima derived radioactive substance has transported to the ECS and YS. In the recent years, 30 nuclear power reactors have been installed in the coastal region of China. The environmental safety and impact of nuclear facilities are highly concerned. 129I, as a fission product, can be used to monitor and evaluate the impact of the nuclear facilities; this requires a baseline value of 129I. However, no such 129I baseline in seawater along the coastal region of China is available.

Iodine is one of redox sensitive elements; it occurs mainly as iodide (I−) and iodate (IO3−) with minor organic iodine in seawater. Iodate is thermodynamically stable and predominant in the open sea11,12, but can be converted to iodide in surface photic zones as well as in oxygen-deprived basins13. Reduction of IO3− to I− in seawater is often related to biological activity such as phytoplankton14, microorganism15. The speciation analysis of the anthropogenic 129I can provide critical information for understanding the marine environment and process.

Due to the increased discharges of pollutants and nutrients, red tide frequently occurs in the ECS and YS in the recent years. Speciation analysis of iodine isotopes can provide a new insight to investigate and evaluate the impact of the pollution. To our best knowledge, no data on the species of iodine isotopes in the ECS has been reported. There are a numbers of water masses and/or water currents in the ECS. The interaction among these water masses directly influences the environment of the ECS. Investigation of the 129I distribution in this region will provide an insight into the exchange and interaction of these water masses.

In this work, surface seawater samples collected in the ECS and its adjacent region were analyzed for iodine isotopes and their species, aiming to provide a baseline dataset of the distribution of 129I and 127I in this region and to trace the exchange and circulation of water masses in this region. The chemical species of 129I and 127I can be used to investigate the marine circumstance and environmental process in the ECS.

Results

Distribution of 129I and 127I in the ECS

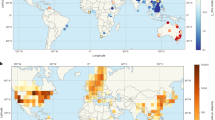

The analytical results of 129I and 127I in the surface seawater in the ECS are listed in Table S2 (Supplementary information). 127I concentrations in the ECS vary significantly in 3.1–54.7 μg/L, the highest value (54.7 μg/L) was observed in the open sea area, which is 8–18 times higher than the lowest values (3.1–7.1 μg/L) in the Yangtze River mouth (station 52–54, Fig. 1a, Supplementary Table S2). In the Yangtze River estuary (stations 24, 32, 42, 47, 51,), the 127I concentrations are relative low in 25.0–37.0 μg/L. Enhanced 127I concentrations (43.2 μg/L in average) were observed the Yangtze River estuary (station 1, 2, 7) and the offshore seawater (stations 3, 13, 14, 25, 33, 38). Further increased concentrations of 127I ranging in 45.1–51.8 μg/L occurred in the southern ECS (stations 26–29, 34–36, 39–41). In the middle and southeast of ECS (stations 15–18, 22), the highest concentrations of 127I (50.15–54.74 μg/L) were measured (Fig. 1a, Table S2).

Spatial distribution of 127I (a) and 129I (b) concentrations and 129I/127I atoms ratios (c) in the surface water in the ECS. This figure was generated using free software ODV4.7.8 (Schlitzer, R., Ocean Data View, http://odv.awi.de, 2015).

129I concentrations vary from 0.7 × 107 to 4.0 × 107 atoms/L (Fig. 1b, Table S2). The high values (1.5–4.0) × 107 atoms/L) were observed in the Yangtze River mouth (stations 52–54) and the Yangtze River estuary (stations 1, 2, 6–9), as well as in the southern Yellow Sea (stations 43–46). The 129I concentrations decrease gradually from the Yangtze River estuary towards east and southeast to the ECS shelf. Low 129I concentrations (0.8–1.1) × 107 atoms/L were measured in the border of the YS and ECS (stations 47–49). In addition, 129I concentrations ((0.7–1.2) × 107 atoms/L) in the eastern ECS (stations of 21, 23, 30, 31) and coastal area in the southern ECS (stations 24, 25, 32) are also low. While, intermediate level ((1.0–1.5) × 107 atoms/L) occurred in the middle and southern ECS (stations of 38–40, 33–37, 26–29 and 13–20) (Fig. 1b, Table S2).

129I/127I atomic ratios vary significantly from 3.2 × 10−11 to 1.2 × 10−9 (Fig. 1c, Table S2), with a similar variation trend as the 129I concentrations. The highest 129I/127I atomic ratios of (90–120) × 10−11 occurred in the Yangtze River mouth (stations 52–54), which are more than 10 times higher than those in the ECS (<10 × 10−11). The lowest 129I/127I ratios ((3.1–6.4) × 10−11) were observed in the eastern and southern ECS (stations 16–20, 21–23, 30–31, 33–37, 39, 41). While, relative high 129I/127I ratios were measured in the southern YS (stations 42–46) (8.9–13.3) × 10−11) and in the Yangtze River estuary (stations 1–3, 6–7, 51) (7.2–13.3) × 10−11).

Chemical species of 127I and 129I and their distribution

Some of surface seawater samples in the ECS were analyzed for 129I and 127I in iodide (I−) and iodate (IO3−) species (Supplementary Table S3). To better understanding the distribution and variation of iodine species, molar ratios of 129I−/129IO3− and 127I−/127IO3− are presented in Fig. 2. In general, 129I−/129IO3− ratios are higher than 127I−/127IO3− in seawater for most sampling stations (Fig. 2). Except for the sampling stations along the Yangtze River mouth (stations 52–54) with 127I−/127IO3− ratios of 0.6–11.9, in the Yangtze River estuary (stations 1 and 51) and station 4 with 127I−/127IO3− ratios of 1.3–28.9, iodide/iodate molar ratios for both 129I and 127I were less than 1 in open sea water (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S3). The highest 129I−/129IO3− ratios (12.0–20.2) were observed in waters at the Yangtze River mouth (stations 53 and 54). While a considerable decrease of 129I−/129IO3− ratio (1.0–1.6) were measured in the Yangtze River estuary towards to the ECS at sampling stations 1 and 51. Low 129I−/129IO3− molar ratios was observed in waters from the south of the Hangzhou Bay and in the open sea waters further to 30°N in the center of the ECS (stations 16–31) and the southern ECS (stations 27–41).

Distribution of iodide/iodate ratios for 129I (upper number) and 127I (number in parentheses) in seawater in the ECS.

This figure was generated using free software ODV4.7.8 (Schlitzer, R., Ocean Data View, http://odv.awi.de, 2015).

Discussion

129I concentrations ((0.73–3.99) × 107 atoms/L) and the 129I/127I atomic ratios ((3.1–120) × 10−11) in the surface water in the ECS is 1–3 orders of magnitude higher than the pre-nuclear value (1.5 × 10−12 for 129I/127I ratio and 0.043 × 107 atoms/L for 129I concentration)16, indicating the dominating anthropogenic source of 129I in the surface seawater in the ECS. The highest 129I level ((1.2–4.0) × 107 atoms/L for 129I concentrations and (10.1–119) × 10−11 for 129I/127I atomic ratios) was observed in Yangtze River mouth and a relative high 129I levels of (1.0–2.5) × 107 atoms/L for 129I concentrations and (7.0–12) × 10−11 for 129I/127I ratios were measured in the southern Yellow Sea, and the 129I levels decline towards to the ECS shelf, the lowest 129I levels ((3.1–6.4) × 10−11 for 129I/127I ratios) in the investigated area were measured in the ECS shelf and southern ECS.

The measured 129I level in surface water in the ECS is more than one order of magnitude lower than that in contaminated seawater. In the North Sea, Baltic Sea, Norwegian Sea and Arctic, 129I/127I ratios of 10−8–10−6 were reported because of huge amount of 129I discharged from the European nuclear fuel reprocessing plants (NFRPs)at Sellafield (UK) and La Hague (France) has dispersed with sea current to these area4,17,18,19,20. In the Fukushima offshore water, the 129I/127I ratios reached to 2.2 × 10−9 (6.3 × 108 atoms/L for 129I concentration) due to the releases from the Fukushima accident10 (Supplementary Table S4).

Compared to the region with similar latitude as the ECS but no direct contamination by human nuclear activity, the 129I level in the ECS is comparable to those observed in adjacent sea around Japan before Fukushima accident, where 129I concentrations of (1.2–2.1) × 107 atoms/L (with 129I/127I ratios of 4.64–7.2 × 10−11) were report6. But it is lower than those in the north Atlantic (31–50°N) (129I concentrations of (4.0–12.7) × 107 atoms/L and 129I/127I ratios of (2–57) × 10−10)3. The higher 129I level in the North Atlantic results from the leakage and southwards dispersion of the high reprocessing derived 129I water in the English Channel. In addition, the 129I in the ECS is also comparable to those observed in the Indian Ocean (40–50°S), where the 129I concentrations were (0.60–1.52) × 107 atoms/L (Fig. 3)21,22. Based on above, it can conclude that 129I in the ECS water fall in normal global fallout background level.

However, the 129I in the ECS continental shelf are higher than that in the South Atlantic Ocean and the Antarctic ((0.05–0.4) × 107 atoms/L for 129I concentrations and (0.28–2.9) × 10−11 for 129I/127I ratios) (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S4)23,24. This should be attributed to less fallout of NWTs derived radioactive substances in the south hemisphere.

The dominantly anthropogenic 129I in the ECS might originate from 1) releases from nuclear facilities in coastal region of the ECS; 2) fallout of the atmospheric NWTs in 1945–1980; 3) releases from NFRPs and long distance transport; 4) nuclear accidents (e.g. Chernobyl and Fukushima accidents).

Although huge amount of 129I has been produced during the operation of the nuclear power plants (NPPs)1, most of it was kept in the fuel elements and only very tiny fraction might be released if leakage of fuel elements occurred. Up to 2013, total 13 nuclear power reactors in 4 NPPs including Qianshan (30.43°N, 120.92°E), Fangjiashan (30.43°N, 120.92°E), Sanmen (29.04°N, 121.62°E), and Fuqing (25.53°N, 119.52°E) in coastal region in the ECS were in operation. However, there is no report on the significant releases of fission products from any of these NPPs. An investigation on the 129I in the seawater surround a Chinese NPP in the coastal region of the ECS has confirmed no excessive 129I in the seawater in 10 km range of this NPP25. There is no any NFRPs or other nuclear facilities surrounding the ECS. Therefore, the direct contribution of nuclear facilities to the 129I in the ECS is negligible.

It has been estimated that 50–150 kg of 129I has been released to the atmosphere from the atmospheric NWTs in 1945–198026. All NWT sites are far from the ECS and the catchment of rivers flowing into the ECS. The nearest testing site at Lop Nor (41°30′N, 88°30′E) is about 3000 km northwest of the ECS, where only 23 atmospheric NWTs were implemented in 1964–1980, An investigation of a sediment core collected in Jiaozhou Bay in the YS has observed a small but obvious 129I signal in 1972–1976, which was attributed to the contribution of Chinese NWTs in this period27. Considering the very small 129I signal of Chinese NWTs in the corresponding layer of this sediment core and these tests were implemented more than 30 years ago, the direct contribution of the Chinese NWTs to the 129I in the ECS, especially the present surface seawater, should be insignificant. However, the global fallout of 129I from all atmospheric NWTs might be one of 129I sources in the ECS because of the large releases. A relative high 129I signal of the global fallout peaked in 1962–1963 has been observed in the sediment core collected in the Jiaozhou Bay27. Compared to the direct deposition of 129I in the ECS in early time of atmospheric NWTs, the leaching of 129I from the earth surface by rainwater and subsequent transport to the ECS through rivers might be one of important source and pathway of 129I in the ECS.

105 NWTs have been conducted in the Pacific Proving Grounds (PPG) in the Marshall Islands (11°N) in 1946–1962, where is about 5000 km southeast of the ECS. Besides those injected to the stratosphere and contributed to the global fallout, large amount of radioactive substances from these NWTs were deposited in the southern Pacific Ocean surrounding the Marshall Islands (close-in fallout). A number of investigations have reported that the close-in fallout of plutonium in the PPG has being carried by the north equatorial current, which is followed by the Kuroshio Current (KC) and continuously transported to the South China Sea and ECS28,29. The constantly significant PPG derived Pu signal observed in the ECS was attributed to the continuous re-suspension of the highly deposited plutonium in the sediment in the PPG region28,29. Compared to plutonium, iodine is water soluble and conservative in ocean, the close-in fallout of 129I at the PPG can be also transported to the ECS in early time of the NWTs at PPG. The 129I in the sediment core collected in Jiaozhou Bay in the YS has recorded a small but obvious PPG derived signal of 129I in 195727. Meanwhile, a similar 129I peak occurred in 1957–1958 in coral samples collected in the coastal region in Philippine has also been reported30, which suggests that PPG derived 129I might have a contribution to 129I in the ECS. However, the distribution of 129I in the ECS shows the lowest 129I level in the east edge of the ECS, i.e. the KC belt, indicating no significant amount of 129I in the ECS was transported from the PPG through the KC. This might be attributed that the NWTs at PPG has terminated in 1962, and transit time from PPG to the ECS is less than 2 years, the high water soluble 129I released from these NWTs did not significantly deposited and remained in the sediment in the PPG area, instead it was quickly diluted and dispersed to a large area with sea currents. Therefore, unlike plutonium, the contribution of the PPG to the 129I in the present surface water in the ECS is insignificant.

Releases from the NFRPs are so far the largest source of 129I in the environment1,2,3,4. A NFRP at Tokai, Japan is the nearest NFRP to the ECS (about 1500 km northeast), which was operated in 1977–2007. A constant low 129I level observed in the precipitation collected in 1979–2003 in Ishigaki-shima (24°N, 124°E)31 located in the east edge of the ECS area indicated no significant influence of Tokai NFRP to 129I level in the ECS. The NFRP in northwest China is far away from the ECS (>5000 km) and the catchment of the rivers (>2000 km) flowing into the ECS. 129I in the sediment core collected in the YS and surface soil collected in southern China did not show any contribution of Chinese NFRP. Therefore, there is no significant contribution of Chinese NFRP to 129I in the ECS.

Besides atmospheric releases, the two NFRPs at Sellafield (UK) and La Hague (France) have discharged more than 6500 kg of 129I to the seas, which was dispersed to a large area in northern North Atlantic Ocean by sea currents26, and an annual discharge of 129I still remains at a high level of about 250 kg/y. Re-emission of the reprocessing derived 129I from the contaminated seawater to the atmosphere has become a major source of 129I in the air in recent years32. The 129I record in the sediment core from the YS has demonstrated that the atmospheric releases of the European NFRPs and re-emission of the reprocessing derived 129I in the sea is a major source of 129I in the present sediment in the YC27. 129I in the Japan Sea was also attributed to the European NFRPs6. All these suggest that the European NFRPs might be the major source of 129I in the ECS besides the global fallout of the NWTs.

The significantly higher 129I level observed in Yangtze River mouth compared to the stations in the ECS indicates that riverine input might be an important source of 129I in the ECS. Yangtze River is the longest river (6300 km length) in China with a catchment area of 1,808,500 km2 located in southern China (25–34°N). The fallout of 129I on the soil of the catchment has being continuously leached by rain and entered to river water, causing a high 129I level in the Yangtze River. The high level 129I in the southern YS indicate a higher deposited and riverine input of 129I from the Yellow River. The YS and the catchment area of the Yellow River are located in north China (32.5–40°N), and therefore received higher fallout of 129I compared to the ECS, because most of NWT sites and NFRPs are located in the middle and higher latitude in the Hemisphere16,33. 129I levels in soil and seaweed in the north China and the YS is higher than that in the south China and the ECS34,35.

Besides the Yangtze River, there are more than 40 rivers flowing into the ECS, among them the relative big ones include Qiantang River (55,600 km2 catchment area and 688 km length), Min River (61,000 km2 catchment area and 577 km length) and Ou River (18,000 km2 catchment and 388 km length). Considering total surface area of 1,940,000 km2, the riverine input from the terrestrial deposition is one of major contribution of 129I in the ECS. This is also supported by investigation on the distributions of another important fallout radionuclide 137Cs in the sediment in the Yangtze River estuary, which showed that the major part of 137Cs in the estuary originated from riverine transport and input36,37.

It has been estimated that 1.3–6 kg 129I has been released from the Chernobyl accident. 131I signal in the atmospheric samples collected at northern China in May 1986 immediately after the Chernobyl accident has been observed, and a small signal of Chernobyl accident derived 129I has been also observed in the sediment collected in the YS27. However, no 131I in the atmosphere in southern China was observed in 1986 after the Chernobyl accident. Considering the small releases, far distance, and happened more than 25 years ago, Chernobyl accident contributed insignificant amount of 129I in the surface water in the ECS.

Fukushima nuclear accident happened in March 2011 has released 1.2 kg 129I including about 0.35 kg 129I discharged directly to the sea, which caused an elevated 129I level in the Fukushima offshore seawater with the highest 129I/127I atomic ratio of 2.2 × 10−9 in the surface seawater near the Fukushima Dai-ichi NPP10. Due to the dominant westerly wind after the accident, the deposition of Fukushima derived radioactive substances were relative low in China, especially in the south China. Consequently, the direct deposition of Fukushima derived 129I in the ECS and the catchment of the rivers flowing into the ECS is insignificant. Marine 129I from the Fukushima accident was mainly transport eastwards in the North Pacific Ocean with the KC. An elevated 129I in the surface seawater has been observed in the North Pacific Ocean in 201338. It is therefore concluded that the Fukushima accident contributed insignificant amount of 129I to the ECS.

Based on the marine dispersion model, it was estimated that the Fukushima derived radioactive substances will arrive in the ECS in 2013 and reach to peak value in 201839, however, the relative low 129I level in the center and eastern ECS compared to the northern and western ECS indicates that Fukushima accident derived 129I has not yet arrived to the ECS, at least not measurable until summer 2013.

The increasing gradient of 127I concentrations and declined 129I level in the surface water from the Yangtze River estuary towards the ECS shelf (Fig. 1) shows an interaction of Yangtze River water with seawater from the KC and TWC, and the mixing model of these water masses (Fig. 1). The high 129I but low 127I level in the riverine water and high 127I but low 129I level in seawater from the TWC and KC makes 129I/127I atomic ratio a perfect indicator to trace the water masses interaction in this region. From the distribution of 127I and 129I concentrations and 129I/127I ratios in the ECS (Fig. 1), it can be observed that the Yangtze River water splits into three branches when it injects into the ECS: one branch moves southwards along the continental shelf of the ECS, extends as far as down to 26°N, showed by rapidly decreased 129I concentrations and 129I/127I ratios along this transport pathway; the second branch moves southeastwards, from the Yangtze River estuary to the continental shelf of the ECS, showed by the decreased 129I/127I ratios from 1.17 × 10−9 to 4.14 × 10−11 at 126°E; in the third branch, Yangtze River water moves northeastwards, encountered the cold water mass from Yellow Sea, the cyclone circulation produced by the cold water mass turns this branch to the east and extend to the Jeju Island. This observation in 2013 is supported by an investigation of depth profiles of conductivity, temperature, and drifter trajectory in the ECS water in the summers of 1997 and 1998, showing the Yangtze River water plume moved eastwards to the offshore and further to Jeju Island40.

A significantly declined 129I level from the southern YS to the ECS was observed for both coast water and offshore water. This trend indicates that the high 129I Yellow Sea water moves from north to south, and meet the high 129I level Yangtze River water from the Yangtze River estuary in the border of the Yellow Sea and ECS, and then turn to northeast at 32°N. 129I concentrations in the surface seawater at the border of the ECS and YC are 1–3 times lower than that in the surrounding region. Meanwhile the 127I concentrations in this region (sampling stations 47 and 48) are relative low (30–33 μg/L). 129I absent ground seepage water input along the shore might occur here. A hypoxic condition observed at sampling station 48 (Supplementary Table S1) supports this assumption. Low salinity and low temperature observed at sampling stations 47–49 also support this assumption. An upwelling zone in the region of 122°00′–123°30′E, 31°–32°30′N (stations 47–48) has also been observed in summer 198541. Therefore, the low 129I and 127I level in this region might results from the groundwater seepage and upwelling of seawater in this region.

Low 129I region observed at the continental slope of the ECS (stations 28, 36 and 41) might indicate a branch of the KC in the ECS in this region. The KC formed from the subtropical mode water of the central North Pacific42 contains low 129I (Fig. 1). The distribution of 129I level indicates that the major KC flows northeastwards along the out edge of the ECS continental shelf, and a small branch moves northwards when it enters the ECS along a transection at stations 28, 36 and 41. The low 129I level at stations 11 and 12 indicates that another branch of the KC moves northwestwards and mixed with the Yangtze River water and the Taiwan warm current (TWC) at about 31°N in the northern ECS.

Low 129I level was also observed along the south coast of the ECS at stations 24, 25 and 32. This might indicate that the high 129I level Yangtze River water does not move southerly along the coast. Considering 127I concentrations are also lower in this region and there is not big river flowing into the ECS in this region, it can be assumed that the groundwater seepage in this region might also occur.

127I mainly exists as iodate with iodide/iodate molar ratios of 0.04–0.60 in most sampling stations in the ECS, this is similar to those observed in the North Sea (0.11–0.48)4,43. The lowest 127I−/127IO3− molar ratio of 0.04 was observed at sampling station 41, close to the Mien Hwa Canyon (MHC) with a northwestwards KC intrusion branch. This might be attributed to the Kuroshio subsurface water (KSW) upwelling in this region44,45, because iodate is normally dominated in deep seawater due to less biological activity. The low iodide/iodate ratios in the continental shelf edge of the ECS might also result from some vortex upwelling, when the KC moves northeastwards along the edge of continental shelf45. Besides the upwelling water, the low iodide fraction (or oxidation condition) in the KC water might be another reason. No significant correlation between 127I−/127IO3− and 129I−/129IO3− ratios (R2 = 0.007) was observed for all seawater samples investigated. Meanwhile 129I−/129IO3− ratios are normally higher than 127I−/127IO3− ratios. This is attributed to the different sources of 127I and 129I in these waters. 129I in the ECS mainly originates from the atmospheric fallout and riverine input, whereas 127I originates from the sea currents which flow into the ECS.

In the Yangtze River mouth, both of 129I and 127I originated from the rainwater leaching of soil in the catchment, the similar high iodide/iodate ratios of 12 for both 127I and 129I were measured at station 54. This indicates iodide is the dominant species of iodine isotopes. This is similar as that observed in the Elbe River in the North Sea4, indicating that the Yangtze River water, at least in the mouth area, is reductive/anoxic water. Declined 127I−/127IO3− ratios of 0.6–1.5 were measured in the downstream water at stations 52 and 53. This might be attributed to the tidal action and sea water intrusion showed by an elevated salinity (0.5) at sampling station 52. The similar declined 129I−/129IO3− ratio (1.5) was measured at station 52, whereas a much higher value up to 20 at sampling station 53. Compared to 127I, 129I−/129IO3− ratios might reflect the water circumstance in this region, because the contribution from the seawater intrusion is minor. The high 129I−/129IO3− ratio at sampling station 53 indicates the reductive circumstance of the Yangtze River water remained at this station. The declined 129I−/129IO3− ratio at station 52 close to the Yangtze River estuary indicates the effluence of the seawater, and the reductive circumstance is changed, causing oxidation of 129I− to 129IO3−.

High 127I−/127IO3− ratios (7–29) were measured at sampling stations 1 and 51 in the ECS, which are even higher than that in the Yangtze River mouth. It has been reported that a red tide (phytoplankton blooming) occurred in the estuary of the Yangtze River in August 2013, and the measured concentrations of chlorophyll were 5.6–37.7 mg/m3 46. The red tide phenomenon was also observed at sampling stations 1, 2 and 51 during the sampling expedition in August 2013. The dominant iodide specie in this region might result from the reductive condition due to the phytoplankton blooming in this region14,47.

High iodide/iodate ratios were also observed at sampling station 4 (1.3 for 127I and 2.9 for 129I), which are comparable or even higher than that in the Yangtze River mouth (stations 52). An oxygen depleted condition was measured in the water at sampling station 3, 4 and 48 during sampling campaign in August 2013. The dominant iodide specie in this region (sampling sate 3–4) might results from the anoxic condition in this region, which reduce iodate to iodide.

Since the total 129I concentrations in the water at the sampling stations 1–4 are similar to those in the southern region at sampling stations 6–9, the elevated 129I−/129IO3− ratios in sampling station 3–4 should be attributed to the reduction of 129IO3− in the sampling region (station 3–4) which was transported from the Yangtze River estuary northwards through the sampling station 6–9. This also indicates that the reduction of iodate in the anoxic region or biologically active region, especially phytoplankton blooming region, is a relative fast process.

Materials and Methods

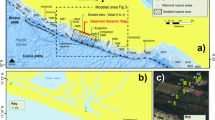

Investigation area

The ECS is the largest marginal sea in the northwestern Pacific, bounded by China, Japan, Ryukyu archipelago, and Korea (Fig. 4). It receives fresh water input from rivers, among them Yangtze River contributes 90% of fresh water input. The KC flows into the ECS through the Channel between Taiwan and Yonaguni-jima Island, and moves northward along the edge of continental shelf. The KC follows the North Equatorial Current in the Pacific Ocean which passes through the PPG in Marshall Islands where 105 NWTs were conducted (11°N) in 1946–1962. The TWC formed by the mixing of the KC surface water and the Taiwan Strait Water, enter the ECS from the Taiwan Strait. In the northern part of the ECS shelf, the Yellow Sea Surface Current flows southwards and participates in the structure of the ECS water masses.

Sampling sites and water masses in the Yangtze River estuary and adjacent seas.

Blue dotes represent the sampling sites of surface water, the numbers aside dots are the sample/station code. The red dotted line represents border of the ECS and Yellow Sea. Yangtz River Diluted Water (YDW, summer), Taiwan Warm Current (TWC), Kuroshio Current Water (KCW). This figure was generated using free software ODV 4.7.8 (Schlitzer, R., Ocean Data View, http://odv.awi.de, 2015).

Collection of the seawater samples

Surface seawater samples (<2 m depth) were collected during the R/V “Dongfanghong 2” cruise in August 2013 using a built-in seawater sampling system in the laboratory of the vessel at 54 sampling stations in the ECS and its adjacent region (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table S1). The temperature and salinity of the seawater samples were measured on-line during sampling (Supplementary Table S-1). Samples were filtered through Φ0.45 μm filter membrane to remove suspended particles in situ and stored in 2.5 L polyethylene plastic containers in dark under normal laboratory conditions until analysis.

Separation of 127I and 129I species from seawater

A modified procedure from Hou et al.4 which is based on anion exchange chromatography was applied to separate iodide and iodate from seawater for measurement of 127I− and 127IO3−. The detailed procedure is presented in the Supporting information.

A modified co-precipitation method from Luo et al.48 was used for separation of iodide and total inorganic iodine from seawater for measurement of 129I. For separation of iodide, after addition of 0.20 mg of 127I− carrier and 200 Bq125I− tracer to 1200 ml seawater, NaHSO3 solution was added to final concentration of 0.3 mmol/L, and then HCl was added to adjust pH to 5.1, 50 mg Ag+ (as 0.10 mmol/L AgNO3) was slowly added to the sample under stirring to coprecipitate iodide as AgI-AgCl. For total inorganic iodine, 500 ml seawater was taken to a beaker, 0.20 mg of 127I− carrier, 200 Bq 125I− (NaI) and 2.0 mmol NaHSO3 solution were added. HCl was then added to adjust pH < 2, iodate was reduced to iodide in this condition. 150 mg Ag+ was slowly added to the solution under stirring to coprecipitate the formed iodide as AgI-AgCl. The precipitate was washing with 1–7.5% ammonium to obtain a final precipitate of 1–3 mg for AMS measurement of 129I.

Procedure blanks for iodide and total inorganic iodine were prepared using the same procedure as for the samples. In this case, deionized water was used instead of the samples.

Measurement of 127I using ICP-MS and 129I by AMS

Iodine in the separated iodate and iodide fractions and original seawater was measured used ICP-MS (Thermo Scientific, X series II, USA) after 10 times dilution using 1% ammonium solution. The detection limit of 0.02 ng/mL for 127I was obtained.

The separated AgI–AgCl coprecipitate was dried in an oven at 60–70 °C, the dried precipitate was ground to fine powder and mixed with niobium powder (325-mesh, Alfa Aesar, Ward Hill, MA) in a mass ratio of 1:5, which was finally pressed into copper holder. The 129I/127I atomic ratios in the prepared targets were measured by AMS using 3MV Tandem AMS system (HVEE) in the Xi’an AMS center. 127I5+ was measured as charges (current) using a Faraday cup and 129I5+ was measured using a gas ionization detector. All samples were measured for 6 cycles and 5 min per sample in each cycle. The procedure background of 129I/127I ratio was measured to be 1.0 × 10−13. For the samples with 129I/127I ratio of 10−10, the measurement uncertainty is less than 1.75%49. A detailed description of AMS system and measurement of 129I has been reported elsewhere50.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Liu, D. et al.129I and its species in the East China Sea: level, distribution, sources and tracing water masses exchange and movement. Sci. Rep. 6, 36611; doi: 10.1038/srep36611 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Hou, X. L. et al. A review on speciation of iodine-129 in the environmental and biological samples. Anal. Chim. Acta. 632, 181–196 (2009).

Jabbar, T., Wallner, G. & Steier, P. A review on 129I analysis in air. J. Environ. Radioact. 126, 45–54 (2013).

He, P., Hou, X. L., Aldahan, A., Possnert, G. & Yi, P. Iodine isotopes species finger printing environmental conditions in surface water along the northeastern Atlantic Ocean. Sci. Rep. 3, doi: 10.1038/srep02685 (2013).

Hou, X. L. et al. Speciation of 129I and 127I in seawater and implications for sources and transport pathways in the North Sea. Environ. Sci. Technol. 41, 5993–5999 (2007).

Karcher, M. et al. Recent changes in Arctic Ocean circulation revealed by iodine-129 observations and modeling. J. Geophys. Res-Oceans. 117, doi: 10.1029/2011jc007513 (2012).

Suzuki, T., Otosaka, S. & Togawa, O. Concentration of iodine-129 in surface seawater at subarctic and subtropical circulations in the Japan Sea. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. B 294, 563–567 (2013).

Suzuki, T., Minakawa, M., Amano, H. & Togawa, O. The vertical profiles of iodine-129 in the Pacific Ocean and the Japan Sea before the routine operation of a new nuclear fuel reprocessing plant. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. B. 268, 1229– 1231 (2010).

Cooper, L. W., Hong, G. H., Beasley, T. M. & Grebmeier, J. M. Iodine-129 concentrations in marginal seas of the North Pacific and Pacific-influenced waters of the Arctic Ocean. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 42, 1347–1356 (2001).

Guilderson, T. P., Tumey, S. J., Brown, T. A. & Buesseler, K. O. The 129-iodine content of subtropical Pacific waters: impact of Fukushima and other anthropogenic 129-iodine sources. Biogeosciences. 11, 4839–4852 (2014).

Hou, X. L. et al. Iodine-129 in Seawater Offshore Fukushima: Distribution, Inorganic Speciation, Sources, and Budget. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 3091–3098 (2013).

Campos, M., Farrenkopf, A. M., Jickells, T. D. & Luther, G. W. A comparison of dissolved iodine cycling at the Bermuda Atlantic Time-Series station and Hawaii Ocean Time-Series Station. Deep-Sea Res. Part II-Top. Stud. Oceanport. 43, 455–466 (1996).

Farrenkopf, A. M., Dollhopf, M. E., NiChadhain, S., Luther, G. W. & Nealson, K. H. Reduction of iodate in seawater during Arabian Sea shipboard incubations and in laboratory cultures of the marine bacterium Shewanellaputrefaciens strain MR-4. Mar. Chem. 57, 347–354 (1997).

Wong, G. T. F. The marine geochemistry of iodine. Rev. Aquatic Sci. 4, 45–73 (1991).

Chance, R., Malin, G., Jickells, T. & Baker, A. R. Reduction of iodate to iodide by cold water diatom cultures. Mar. Chem. 105, 169–180 (2007).

Amachi, S. Microbial Contribution to Global Iodine Cycling: Volatilization, Accumulation, Reduction, Oxidation, and Sorption of Iodine. Microbes. Environ. 23, 269–276 (2008).

Snyder, G., Aldahan, A. & Possnert, G. Global distribution and long-term fate of anthropogenic 129I in marine and surface water reservoirs. Geochem. Geophy. Geosyst. 11 (2010).

Yi, P., Aldahan, A., Hansen, V., Possnert, G. & Hou, X. L. Iodine Isotopes (129I and 127I) in the Baltic Proper, Kattegat, and Skagerrak Basins. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 903–909 (2011).

He, P., Aldahan, A., Possnert, G. & Hou, X. L. Temporal Variation of Iodine Isotopes in the North Sea. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 1419–1425 (2014).

Atarashi-Andoh, M. et al. 129I/127I ratios in surface waters of the English Lake District. Appl. Geochem. 22, 628–636 (2007).

He, P., Hou, X. L., Aldahan, A. & Possnert, G. Radioactive 129I in surface water of the Celtic Sea. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 299, 249–253 (2014).

Povinec, P. P. et al. radiocarbon, 90Sr and 129I in the Pacific and Indian Oceans. Nuclear. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. B. 268, 1214–1218 (2010).

Povinec, P. P. et al. Tracing of water masses using a multi isotope approach in the southern Indian Ocean. Earth. Planet. Sci. Lett. 302, 14–26 (2011).

Negri, A. E. et al. 129I Dispersion in Argentina: Concentrations in Fresh and Marine Water and Deposition Fluences in Patagonia. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 9693–9698 (2013).

Xing, S. et al. Iodine-129 in snow and seawater in the Antarctic: level and source. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 6691–6700 (2015).

He, C. H. et al. 129I level in seawater near a nuclear power plant determined by accelerator mass spectrometer. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A. 632, 152–156 (2011).

Aldahan, A., Alfimov, V. & Possnert, G. 129I anthropogenic budget: Major sources and sinks. Appl. Geochem. 22, 606–618 (2007).

Fan, Y. K., Hou, X. L., Zhou, W. J. & Liu, G. 129I record of nuclear activities in marine sediment core from Jiaozhou Bay in China. J. Environ. Radioact. 154, 15–24 (2016).

Wu, J. W. et al. Isotopic composition and distribution of plutonium in Northern south China Sea sediments revealed continuous release and transport of Pu from the Marshall Islands. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 3136–3144 (2014).

Wang, Z. L. & Yamada, M. Plutonium activities and 240Pu/239Pu atom ratios in sediment cores from the East China Sea and Okinawa Trough: Sources and inventories. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 233, 441–453 (2005).

Bautista, A. T., Matsuzaki, H. & Siringan, F. P. Iodine-129 in two coral cores from the Philippines as a tracer of anthropogenic nuclear activities and atmosphere ocean transport. In: The 6th East Asia Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Symposium. (2015).

Toyama, C., Muramatsu, Y., Igarashi, Y., Aoyama, M. & Matsuzaki, H. Atmospheric fallout of 129I in Japan before the Fukushima accident: regional and global contributions (1963–2005). Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 8383–8390 (2013).

Zhang, L. Y., Hou, X. L. & Xu, S. Speciation of 127I and 129I in atmospheric aerosols at Risø, Denmark: insight into sources of iodine isotopes and their species transformations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 1971–1985 (2016).

Reithmeier, H., Lazarev, V., Ruehm, W. & Nolte, E. Anthropogenic 129I in the atmosphere: Overview over major sources, transport processes and deposition pattern. Sci. Total. Environ. 408, 5052–5064 (2010).

Hou X. L., Dahlgaard H., Nielsen S. P. & Ding W. J. Iodine-129 in human thyroid and seaweed in China. Sci. Total. Environ. 246, 285–291 (2000).

Fan, Y. K. Spatial distribution of 129I in Chinese surface soil and preliminary study on the 129I chronology. PhD thesis, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences (2013).

Su, C. C. & Huh, C. A. 210Pb 137Cs and 231Pu, 240Pu in East China Sea sediments: sources, pathways and budgets of sediments and radionuclides. Mar. Geol. 183, 163–178 (2002).

Huh, C. A. & Su, C. C. Sedimentation dynamics in the East China Sea elucidated from 210Pb, 137Cs and 239Pu, 240Pu. Mar. Geol. 160, 183–196 (1999).

Stan-Sion, C., Enachescu, M. & Petre, A. R. AMS analyses of 129I from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident in the Pacific Ocean waters of the Coast La Jolla-San Diego, USA. Environ. Sci-Proc & Imp. 17, 932–938 (2015).

Zhao, C., Qiao, F. L., Wang, G. S., Xia, C. S. & Jung, K. T. Simulation and prediction of 137Cs from the Fukushima accident in the China Seas. Chin. Sci. Bull. 59, 3416–3423 (2014).

Lie, H. J., Cho, C. H., Lee, J. H. & Lee, S. Structure and eastward extension of the Changjiang River plume in the East China Sea. J. Geophys. Res-Oceans 108 (2003).

Yi, Q. Advances in the offshore circulating current of Jiangsu. Sci. Technol. Eng. (Chin.) 9, 3389–3394 (2009).

Hsueh, Y. The Kuroshio in the East China Sea. J. Mar. Syst. 24, 131–139 (2000).

Truesdale, V. W. & Upstill-Goddard, R. Dissolved iodate and total iodine along the British east coast. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 56, 261–270 (2003).

Wong, G. T. F., Chao, S. Y., Li, Y. H. & Shiah, F. K. The Kuroshio edge exchange processes (KEEP) study - an introduction to hypotheses and highlights. Cont. Shelf. Res. 20, 335–347 (2000).

Lie, H. J. & Cho, C. H. Recent advances in understanding the circulation and hydrography of the East China Sea. Fish. Oceanogr. 11, 318–328 (2002).

Liu, Y. Y., Shen, F. & Li, X. Z. Phytoplankton light absorption properties during the blooms in adjacent waters of the Changjiang estuary. Environ. Sci. (China) 36, 2019–2027 (2015).

Bluhm, K., Croot, P., Wuttig, K. & Lochte, K. Transformation of iodate to iodide in marine phytoplankton driven by cell senescence. Aquat. Biol. 11, 1–15 (2010).

Lou, M. Y., Hou, X. L., He, C. H., Liu, Q. & Fan, Y. K. Speciation Analysis of 129I in Seawater by Carrier-Free AgI–AgCl Coprecipitation and Accelerator Mass Spectrometric Measurement. Anal. Chem. 85, 3715–3722 (2013).

Zhou, W. J. et al. New results on Xi’an-AMS and sample preparation systems at Xi’an-AMS Center. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. B 262, 135–142 (2007).

Hou, X. L. et al. Determination of Ultralow Level 129I/127I in Natural Samples by Separation of Microgram Carrier Free Iodine and Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Detection. Anal. Chem. 82, 7713–7721 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Ministry of Science and Technology of China (Grant No. 2015FY110800), State Key Laboratory of Estuarine and Coastal Research (SKLEC-KF201402) and State Key Laboratory for Loess and Quaternary Geology. D. Liu appreciates Dr. Q. Liu for the AMS measurement of 129I, Dr. S. Xing for his help in the sample preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the planning of the project. D.L. analyzed all water samples for species of iodine isotopes and prepared first draft of the paper. X.H. designed the research program, interpreted the data and finalized the manuscript. J.D. collected all seawater samples. All author participated in the revision of the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, D., Hou, X., Du, J. et al. 129I and its species in the East China Sea: level, distribution, sources and tracing water masses exchange and movement. Sci Rep 6, 36611 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36611

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36611

This article is cited by

-

Iodine isotopes in surface water in the Northeast Asia

Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry (2023)

-

On the determination of 36Cl and 129I in solid materials from nuclear decommissioning activities

Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry (2022)

-

Determination of 129I in vegetation using alkaline ashing separation combined with AMS measurement and variation of vegetation iodine isotopes in Qinling Mountains

Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry (2020)

-

The effect of boron on zeolite-4A immobilization of iodine waste forms with a novel preparation method

Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry (2020)

-

Radioanalysis of ultra-low level radionuclides for environmental tracer studies and decommissioning of nuclear facilities

Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.