Abstract

Streptococcus pyogenes is a globally prominent bacterial pathogen that exhibits strict tropism for the human host, yet bacterial factors responsible for the ability of S. pyogenes to compete within this limited biological niche are not well understood. Using an engineered recombinase-based in vivo expression technology (RIVET) system, we identified an in vivo-induced promoter region upstream of a predicted Class IIb bacteriocin system in the M18 serotype S. pyogenes strain MGAS8232. This promoter element was not active under in vitro laboratory conditions, but was highly induced within the mouse nasopharynx. Recombinant expression of the predicted mature S. pyogenes bacteriocin peptides (designated SpbM and SpbN) revealed that both peptides were required for antimicrobial activity. Using a gain of function experiment in Lactococcus lactis, we further demonstrated S. pyogenes immunity function is encoded downstream of spbN. These data highlight the importance of bacterial gene regulation within appropriate environments to help understand mechanisms of niche adaptation by bacterial pathogens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A Streptococcus) is a human-adapted bacterial pathogen responsible for non-invasive infections such as pharyngitis and impetigo, severe invasive diseases including necrotizing fasciitis and toxic shock syndrome, and post-infection autoimmune disorders such as rheumatic heart disease1. Global morbidity and mortality due to S. pyogenes is substantial, previously estimated at over 600 million throat infections, at least 18 million invasive infections, and more than 500,000 deaths each year2,3. Despite this massive burden of disease, the biological niche of S. pyogenes represents a state of asymptomatic colonization on the skin and in the nasopharynx4. Although S. pyogenes has evolved multiple mechanisms to subvert host immune responses and cause disease5,6,7, it remains unclear how this bacterial pathogen successfully competes with the numerous members of the endogenous microbiota within the nasopharyngeal microenvironment.

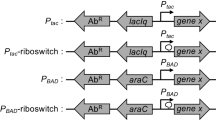

In order to gain a more complete understanding of the molecular basis of S. pyogenes niche adaptation, we engineered a recombinase-based in vivo expression technology (RIVET) system8 using the Cre-loxP system9 to identify genes that are specifically induced within a model in vivo environment. Variations of this ‘promoter trap’ strategy have now been successfully applied to a variety of important bacteria including Vibrio cholera8,10, Mycobacterium tuberculosis11, Bordetella pertussis12, Staphylococcus aureus13, Lactobacillus plantarum14, and Enterococcus faecalis15. In this work, we integrated an engineered loxP-flanked tetracycline resistance cassette (tetR) into a neutral site within the S. pyogenes chromosome. We demonstrate robust stability of the cassette in the absence of the Cre recombinase, and complete and specific resolution of the cassette under artificial Cre expression. We subsequently screened a random chromosomal library of potential promoter fragments by growth in standard laboratory medium, and an in vivo model of acute nasopharyngeal infection. Using this system, we identified a promoter that was located upstream of a potential Class IIb bacteriocin system annotated as the bacteriocin-like peptide (blp) operon that was very weakly expressed in vitro, but highly induced in vivo. Here we designate these genes as the S. pyogenes bacteriocin (spb) locus, and show that this system encodes active antimicrobial peptides and immunity function, providing a potential novel mechanism by how S. pyogenes may compete with other members of the nasopharyngeal microbiota.

Results

Construction of the loxP-tetR-loxP RIVET cassette in S. pyogenes MGAS8232

In order to engineer a RIVET system in S. pyogenes, we integrated a loxP-flanked antibiotic resistance cassette into the chromosome of S. pyogenes MGAS8232. We first selected a 165-bp intergenic region suitable for insertion of foreign DNA sequences. This intergenic region was located between two previously predicted Rho-independent transcriptional terminators16, each located downstream of the divergently transcribed endopeptidase O (pepO) and elongation factor Ts (tsf) genes. This region is highly conserved among other sequenced genomes of S. pyogenes and may represent a suitable location for in trans chromosomal complement experiments. We then integrated an engineered 2,976-bp gene cassette into the tsf/pepO intergenic region using the pG+host5 temperature sensitive integration vector17. This gene cassette was flanked by loxP recognition sites for the Cre-recombinase, and contained both a tetracycline resistance (tetR) gene, as well as a S. pyogenes codon optimized thymidine kinase from Herpes simplex virus (HSV-tk) (Fig. 1A). The HSV-tk gene was engineered initially for use as a counter selection system in conjunction with ganciclovir for the second round of the RIVET procedure; unfortunately, this gene was only intermittently functional in S. pyogenes and although HSV-tk was included in the cassette, we instead relied on colony patching for tetracycline sensitivity during the second round of screening (described below). The correct integration of the loxP-tetR-loxP cassette was verified by PCR and DNA sequencing, and this clone was designated S. pyogenes MGAS8232 Cas2. Furthermore, we also confirmed similar transcription levels of pepO and tsf by qPCR in wild-type MGAS8232 and MGAS8232 Cas2 (Fig. 1B).

Overview and functionality of the RIVET system in S. pyogenes.

(A) Scale schematic of the 2976-bp RIVET cassette containing an antibiotic resistance cassette (tetR) and herpes virus thymidine kinase (HSV-tk), flanked by two loxP sequences and inserted between the tsf and pepO gene in S. pyogenes. (B) qRT-PCR analysis of the RIVET cassette integration site comparing wild-type S. pyogenes MGAS8232 with MGAS8232 Cas2. Data represents the mean ± SEM of three biological replicates and statistical significance is displayed as ***p < 0.001 by Student’s t-test. (C) S. pyogenes Cas2 containing the RIVET cassette was transformed with empty vector (pMSP3535), or pMSP3535 containing cre in the reverse (pMSP3535::cre-reverse) or forward (pMSP3535::cre-forward) orientations, both under the control of the nisin-inducible promoter18. Strains were grown with or without the addition of nisin (100 ng/ml) as indicated and plated on THY agar containing erythromycin or erythromycin and tetracycline. Dilutions of bacteria prior to plating are shown on the left.

Next, to evaluate the functionality of the loxP-tetR-loxP cassette, we transformed MGAS8232 Cas2 with the erythromycin resistant pMSP3535 vector containing the nisin inducible promoter18, and pMSP3535 containing cre in the forward direction (pMSP3535::cre-forward). As an additional control, we also generated a construct containing cre in the reverse orientation to the nisin promoter (pMSP3535::cre-reverse). Transformants were grown in liquid THY, and separately in THY containing 100 ng/ml nisin, and plated on erythromycin, or erythromycin and tetracycline containing media to assess cassette resolution under Cre induction. The addition of nisin did not result in the loss of tetracycline resistance for S. pyogenes Cas2 containing either the pMSP3535 vector, or the pMSP3535::cre-reverse plasmid, whereas colonies were not recovered from cells containing pMSP3535::cre-forward under tetracycline selection (Fig. 1C). Some tetracycline resistance was also lost in the absence of nisin in cells containing pMSP3535::cre-forward; this can be explained by apparent leakiness of the nisin promoter in the absence of induction. Furthermore, sequencing across the resolved cassette region revealed a precise excision of the cassette leaving only a single loxP site. These data indicate that a functional loxP-tetR-loxP RIVET cassette was engineered into the chromosome of S. pyogenes MGAS8232, and that this cassette is stable in the absence of Cre expression under in vitro growth conditions.

Generation of a S. pyogenes MGAS8232 promoter RIVET library

To generate a plasmid for use in the promoter library, we cloned the cre gene into the low-copy E. coli/Gram-positive bacterial shuttle vector pTRKL219. Transformation of pTRKL2::cre into S. pyogenes Cas2 did not result in detectable cassette resolution based on the tetracycline resistance phenotype. Next, genomic DNA from wild-type MGAS8232 that was partially digested with Sau3AI was ligated into the promoterless pTRKL2::cre, and the library was transformed into E. coli XL1-Blue. PCR of random clones from the library was used to verify that a variety of fragments were inserted and most clones contained inserts between 40-bp to ~1000-bp. Clones were subsequently pooled from plates, and plasmids were isolated and transformed as a mixture into S. pyogenes Cas2. Cells were subsequently grown in liquid for 48 h in the presence of erythromycin for plasmid maintenance, and tetracycline to remove any cells that had resolved the cassette through the induction of Cre via an in vitro-active promoter region. These cells were then pooled, enumerated, and frozen until used in the in vivo nasopharyngeal infection model.

Identification of S. pyogenes MGAS8232 promoter elements induced in vivo using an acute nasopharyngeal infection model

Approximately 1 × 108 cells from the promoter library in S. pyogenes Cas2 were used to inoculate the nasal passages of mice as described in Methods. After 48 h, mice were euthanized and the nasal passages were harvested as described20, and bacteria were plated onto media containing erythromycin. Individual clones were subsequently patched onto media containing tetracycline to identify tetracycline-sensitive clones with resolved cassettes, and therefore potentially containing in vivo-induced promoters. Plasmids were extracted from a total of 177 tetracycline sensitive clones, inserts were sequenced, and BLASTn was used to match the putative promoter sequences to the S. pyogenes MGAS8232 genome. Strikingly, none of the 177 clones lacked an insert. From this pool, removal of duplicated sequences produced 82 clones containing unique sequences. However, within this pool we also obtained 21 clones that contained multiple inserts, likely due to cloning artifacts, and due to potential transcriptional read-through the analysis of these clones was compromised and they were not included within our dataset. In total, we obtained 61 unique clones with single inserts, and each clone is listed in Table S1. Based on the sequence orientation and location relative to annotated ORFs, we found three types of clones, similar to those described previously15. These included ‘typical promoters’ that contained sequences within the 5′-untranslated regions upstream of an ORF, ‘cryptic promoters’ that were found entirely within, and in the same orientation, of an ORF, and ‘antisense promoters’ that were located in the opposite orientation to annotated ORFs. From this pool, we identified 9 sequences consistent with ‘typical’ promoters, located upstream of open reading frames and these are summarized in Table 1. Although we have no additional evidence that the remaining clones represent true in vivo-induced promoters, this initial categorization may prove useful for future studies involving anti-sense regulation in S. pyogenes.

PspbM is an in vivo-induced promoter

From the RIVET screen, we selected clone IVI156 for further analysis (Table 1). The plasmid from IVI156 contained a 984-bp sequence upstream and encompassing the 5′ end of SPYM18_RS02350, a potential bacteriocin peptide structural gene homologous to blpM from Streptococcus pneumoniae21. Immediately downstream of SPYM18_RS02350 was an additional ORF (SPYM18_RS02355) with homology to S. pneumoniae blpN21. As described below, and to avoid confusion between the two systems, we designate these ORFs as the S. pyogenes bacteriocin M (spbM) and spbN genes.

The plasmid from clone IVI156 was designated pTRKL2::PspbM::cre. This plasmid, and the vector control (pTRKL2::cre) were retransformed into S. pyogenes Cas2 and clones were grown in vitro for 24 h in THY broth. Neither the vector control or pTRKL2::PspbM::cre induced detectable excision of the loxP-tetR-loxP cassette as determined by comparing CFUs on medium containing erythromycin, or medium containing both erythromycin and tetracycline (Fig. 2A). Next, we conducted the nasopharyngeal infection model using S. pyogenes Cas2 containing either the pTRKL2::cre vector, or pTRKL2::PspbM::cre, and following 48 h, harvested the complete nasal turbinates and plated cells directly on medium containing erythromycin, or erythromycin and tetracycline. As expected, S. pyogenes Cas2 containing the promoterless pTRKL2::cre plasmid did not induce excision of the loxP-tetR-loxP cassette (Fig. 2B). Although S. pyogenes Cas2 containing pTRKL2::PSpbM::cre trended to infect the mice at lower levels compared with Cas2 containing the vector control, the infection with S. pyogenes Cas2 containing pTRKL2::PSpbM::cre resulted in a complete loss of tetracycline resistant colonies (Fig. 2B). These data provide important evidence that PspbM was not functionally expressed in this system under in vitro conditions, but that PspbM was induced during the model nasopharyngeal in vivo environment.

The S. pyogenes bacteriocin promoter (PspbM) is an in vivo-induced promoter.

S. pyogenes Cas2 containing pTRKL2::cre (vector control) or S. pyogenes clone IVI156 (encoding the PspbM promoter) were assessed for cassette resolution by growing cells under in vitro or in vivo conditions as described in Methods. For in vivo conditions, mice were infected with 1 × 108 CFUs of S. pyogenes intranasally for 48 hours. Mice were then sacrificed and the complete nasal turbinates were harvested for bacterial enumeration. Each dot represents CFUs from an individual experiment, and cells were plated on THY agar containing erythromycin, or erythromycin plus tetracycline, and CFUs determined. The black bar represents the geometric mean and statistical significance is displayed as **p < 0.001 by Student’s t-test. The dotted line represents the theoretical limit of detection.

To confirm that PspbM was in fact induced in vivo, we conducted qRT-PCR experiments of spbM transcripts from wild-type S. pyogenes MGAS8232 grown under in vitro (Fig. 3A) or in vivo (Fig. 3B) conditions. Consistent with the data using MGAS8232 Cas2 containing pTRKL2::PspbM::cre, spbM transcripts were very weakly expressed in vitro relative to the gyrA housekeeping gene, yet spbM transcripts were significantly increased at 48 h from the in vivo nasopharyngeal infection model (Fig. 3C). These data provide direct evidence that spbM from wild-type MGAS8232 was specifically induced in the in vivo nasopharyngeal environment.

Analysis of spbM gene expression in vitro and in vivo.

S. pyogenes MGAS8232 was grown (A) in THY broth to OD600 ~0.2 or ~0.9 (n = 3; early and late in vitro conditions, respectively) or (B) nasally inoculated into mice and harvested at 48 h (n = 4; in vivo conditions) as described in Methods. The black bar represents the geometric mean. (C) Expression of spbM was determined by qRT-PCR and normalized to the gyrA housekeeping gene. The graph shows the mean ± SEM and statistical significance is displayed as *p < 0.05 by ANOVA with Tukey’s Multiple Comparison Test.

Bioinformatic analysis of the S. pyogenes spb operon

Clone IVI156 contained sequences consistent with a known promoter region driving the expression of spbM in S. pyogenes JS9522, and is adjacent and in opposite orientation to the streptococcal invasion locus (sil)23 (Fig. 4A). Class IIb bacteriocins exert optimal antibacterial activity when two peptides, encoded in tandem, are present24. The spbM and downstream spbN genes encode for peptides that share hallmarks of the Class IIb bacteriocins, including GXXXG motifs24. SpbM and SpbN contain four and five GxxxG motifs, respectively, which allow for helix-helix interactions between the two peptides to create a membrane penetrating structure24. The peptide sequence encoded by the spbM gene in S. pyogenes MGAS8232 showed 50% identity to BlpM from S. pneumoniae, while the peptide sequence encoded by spbN in S. pyogenes showed 35% identity to the S. pneumoniae BlpN21 (Fig. 4B). In addition, most Class II bacteriocins require a dedicated transport apparatus that recognizes and cleaves a specialized ‘double-glycine-type’ leader peptide25. Both S. pyogenes SpbM and SpbN, as with the S. pneumoniae system, contain sequences consistent with double-glycine-type leader peptides (Fig. 4B). For the bacteria to prevent self-killing by the bacteriocin, the producing organism encodes an immunity peptide that is invariably linked to the structural bacteriocin genes. It is likely, based on typical Class II bacteriocin operon structure24, that one of the genes located downstream from spbN encodes this function, similar to the S. pneumoniae system21. Downstream of spbN are two potential ORFs each which may encode immunity function to the SpbMN bacteriocin (Fig. 4A). The first ORF is not annotated in the MGAS8232 genome, while the second ORF is designated SPYM18_RS02360.

The sil-spb loci in S. pyogenes MGAS8232.

(A) Open reading frame map and DNA sequence of the sil and spb operons. The silD gene in MGAS8232 contains a premature stop codon and may potentially encode two separate ORFs labeled silDN and silDC (the latter denoted with hashed lines). The nucleotide and translation products for the spb locus are given below for the indicated region. The location of the DNA region contained within clone IVI156 is indicated. Promoter regions are drawn as black arrows and direct repeats (DR1 and DR2) are annotated as previously determined in S. pyogenes JS9542. Nucleotide numbers are according to the genome sequence of S. pyogenes MGAS8232 (NC_003485.1). (B) Alignment of the Spb peptides from S. pyogenes MGAS8232 and Blp peptides from S. pneumoniae 6A21. Identical (*) and similar (+) residues are indicated. The arrow (↓) indicates the predicted cleavage site of the double-glycine-type leader peptides.

In addition to the bacteriocin structural and immunity genes, Class IIb bacteriocins also require dedicated transporters, and additionally, often encode proteins involved in self-regulation21. Upstream of spbM in MGAS8232 was a group of genes that correspond to the streptococcal invasion locus (sil)23. The sil locus is comprised of an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter (silDE), a pheromone (silCR), a peptide (silC), and a two-component system (silAB). The sil locus has been shown to be important for invasive infections23,26 and can regulate spbMN and its associated immunity gene in S. pyogenes JS9522. MGAS8232 encodes a full-length silE predicted to produce a 717 amino acid ATP-binding cassette transporter. However, in MGAS8232 silD (SPYM18_RS02340) appears to be a truncated form of the complete 454 amino acid SilD, which normally works in conjunction with SilE to form an ABC transporter complex. Analysis of the nucleotide sequence revealed that a deleted adenine would predict early termination of MGAS8232 silD (designated here as silDN). Although a potential downstream ORF could theoretically encode the C-terminus of this protein (designated here as silDC), there were no obvious translation initiation sequences preceding silDC and this hypothetical ORF is likely not translated (Fig. 4A).

The Spb operon encodes a functional Class IIb two-peptide bacteriocin

Although Class II bacteriocins, to our knowledge, have not been characterized from S. pyogenes, this organism is well known to be capable of producing lantibiotic-type Class I bacteriocins, including salivaricin A (SalA)27, and streptin (StrA)28. MGAS8232 does encode salivaricin A29, although the operon contains a large deletion in the salM and salT genes27. Nevertheless, we tested wild-type MGAS8232 for bacteriocin production in vitro using a standard deferred antagonism assay against a defined set of 9 bacteriocin indicator strains30; however, we did not detect any bacteriocin activity from MGAS8232 in vitro.

Since transcription of the spb system in MGAS8232 was barely detectable in vitro (Fig. 3), in order to assess the ability of SpbM and SpbN from MGAS8232 to function as a Class IIb bacteriocin, we produced recombinant mature peptides from E. coli. A series of indicator strains were tested by 1% inoculation of molten 1.5% agar medium, followed by punching wells into the solidified agar. SpbM alone demonstrated weak activity against a number of indicators whereas SpbN alone did not display any detectable antimicrobial activity. When SpbM and SpbN were mixed however, clear zones of inhibition were seen against multiple S. pyogenes strains (MGAS8232, MGAS5005, SF370), as well as strains of Streptococcus dysgalactiae, Streptococcus uberus, Micrococcus leuteus and Lactococcus lactis. To further evaluate the two-component nature of SpbM and SpbN, we placed these recombinant peptides (~1 μg each) at increasing distances within wells on agar plates and evaluated antimicrobial activity using L. lactis as an indicator. As demonstrated in Fig. 5, optimal antimicrobial activity required the presence of both SpbM and SpbN indicated by zones of inhibition where the two peptides had diffused together. These data demonstrate that the SpbMN peptides can function as a Class IIb bacteriocin.

Spb immunity function is encoded downstream of spbN

In order to assess potential immunity function encoded within the spb operon, we conducted gain-of-function experiments in the SpbMN sensitive host L. lactis MG1363. We first cloned the potential ORF immediately downstream of spbN into the Gram-positive expression vector pMG36e, which contains the constitutive lactococcal promoter P3231. This plasmid did not induce resistance to SpbMN when transformed into L. lactis MG1363 (data not shown). We then generated a construct that contained both this gene, and SPYM18_RS02360, which we designate pMG36e::spbI/RS02360. When pMG36e::spbI/RS02360 was transformed into L. lactis MG1363, these cells became resistant to recombinant SpbMN compared with cells containing the pMG36e vector (Fig. 6). This data indicates that immunity function to SpbMN is encoded downstream of spbN.

Discussion

Humans are the only recognized niche for S. pyogenes, and the upper respiratory tract and skin represent the dominant reservoirs for this globally important pathogen32. In this work, we adapted the RIVET strategy8 to isolate in vivo-activated promoters in S. pyogenes using a model of upper respiratory tract infection to help understand the genetic mechanisms that contribute to infection and persistence. A key advantage to utilizing RIVET over other genomic technologies is the ability to select transiently expressed genes during the course of the environmental exposure that could be missed using genomic technologies that rely on specific time points. Additionally, RIVET can also theoretically detect bacterial genes induced from minor populations of heterogeneous (non-synchronous) cells. Overall, our analysis generated 61 unique clones with single inserts from S. pyogenes MGAS8232 that had apparently resolved the loxP-tetR-loxP cassette in vivo (Table S1).

From the group of ‘sense’ clones, nine appeared to represent typical promoters, likely driving the expression of a gene(s), including clone IVI156 that would control the expression of the spb operon. Bacteriocins from Gram-positive bacteria are small, ribosomally synthesized antimicrobial peptides that typically demonstrate activity against closely related organisms33. There are three major classes of bacteriocins including: Class I bacteriocins (<10 kDa), also termed lantibiotics, that undergo post-translational modification to incorporate lanthionine or β-methyllanthionine residues into the active peptide; Class II bacteriocins (<10 kDa) that are typically not post-translationally modified except for leader peptide cleavage and disulfide bond formation; and Class III bacteriocins (>10 kDa). It is widely thought that bacteriocins exist as factors to compete with other bacteria for ‘space’ within a niche21,34. Since the upper respiratory tract in humans contains a highly complex microbiota35, including many species of streptococci36, it is not surprising that organisms that exist within this environment produce bacteriocins. It has also been demonstrated that endogenous or exogenous (e.g. probiotic) oral streptococci can compete with S. pyogenes, potentially through the use of bacteriocins37, although to our knowledge, there is no direct evidence as to how S. pyogenes itself can compete within this complex microbiota. However, the homologous BlpM/BlpN system in S. pneumoniae strain 6A has been shown to be functionally active and important for intraspecies competition in vivo21 and it will be of interest in future work to compare these systems for the ability to cross complement in terms of both antimicrobial and immunity function.

Although the spb operon has been annotated as ‘Blp-like”, to our knowledge this work is the first to formally demonstrate functional Class IIb bacteriocin peptides in S. pyogenes. Following the re-passaging of the S. pyogenes Cas2 containing pTRKL2::PspbM::cre through the in vivo model produced a striking reduction in tetracycline resistant clones (Fig. 2). In 6 independent mice, we were unable to recover clones with an intact cassette indicating that PspbM was uniformly induced in vivo, at least in cells that were recoverable from the in vivo environment. However, our analysis also indicates that the sil locus is not likely operational in MGAS8232 given the apparent truncation of silD. Interestingly, and as previously noted, most strains of S. pyogenes actually lack the majority of the sil locus38; however, other than S. pyogenes M1 serotypes which contain an 11-bp deletion resulting in a frame-shift mutation within the spbM coding sequence [e.g. strains SF37039, MGAS500540 and M1_47641], most sequenced S. pyogenes strains contain complete spbM and spbN sequences. Furthermore, two direct repeats (DRs) in the spbM promoter region have been shown to be important for regulation by the SilA and SilB two-component system42, and that the length of an 11-bp spacer between both DRs was critical for function. Verified via sequencing, MGAS8232 contains a 10-bp spacer length in DR2 (Fig. 4A), and when the spacer was shortened to 10-bp in S. pyogenes JS95, promoter activity was eliminated. Therefore, although a functional sil locus is clearly able to regulate spbM in some strains of S. pyogenes22,42, our work suggests that an additional regulatory system that can respond to an in vivo signal is able to activate the spbM promoter. Given the truncation of silD in MGAS8232, it remains unclear as to how the SpbMN peptides would gain access to the extracellular milieu. Given the frequent conservation of the spb system in the absence of sil, the Spb peptides could be exported through a currently unidentified transporter. Alternatively, given the nasopharyngeal environment where this system is induced, bacterial cell lysis mediated through the immune system, other competing microbes, and/or potentially the induction of lysogenic bacteriophage from the genome of S. pyogenes, could each provide a mechanism by which the SpbMN peptides are released. However, immature Class II bacteriocins are only weakly active, while removal of the double-glycine-type leader greatly enhances antimicrobial activity43,44. Processing of bacteriocin double-glycine-type leaders is thought to be coupled with export via an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) translocator which commonly contains a N-terminal peptidase belonging to the C39 family of peptidases43,45. Utilizing the MEROPS database46, S. pyogenes MGAS8232 contains a C39 peptidase motif within SilE, and an additional C39 peptidase motif in an ORF located ~5500 bp upstream of silA (locus tag SPYM18_RSO2285). The peptidase domain of bacteriocin ABC transporters are cytoplasmic47, and this domain can also function in isolation from the transporter48, so either gene could potentially provide machinery for leader cleavage of the Spb peptides. If operational, this ‘release by lysis’ mechanism would be functionally analogous to colicin release by E. coli49. Ongoing experiments are focused on elucidating this potential process, and which specific gene(s) possess immunity function.

The sil locus was first characterized from S. pyogenes strain JS95 (serotype M14) using a modified signature-tagged mutagenesis (STM) approach termed polymorphic-tag-length-transposon-mutagenesis (PTTM). A mutant was identified with a transposon insertion within the silC gene, and along with additional specific mutations within the sil locus, this work demonstrated that strains with mutations within the sil locus were severely attenuated for invasive and fatal mouse infections23. Kizy and Neely50 also utilized an STM approach with the M14 serotype S. pyogenes HSC5 in a zebrafish necrotizing fasciitis model. This study identified attenuated strains with transposons in both the silB and silC genes50, encoding the histidine kinase of the sil two-component system and the signaling peptide, respectively22. Including our work presented here, there are now three independent in vivo genomic selection systems that have each identified genes linked to the sil-spb locus in S. pyogenes. The sil locus, and the spb bacteriocin genes, have also recently been shown to be inducible through sensing of host cell asparagine production using the TrxSR two-component system, via a streptolysin dependent mechanism; however, regulation of the bacteriocin genes required a functional sil locus51. We thus favor that, when present, a functional sil locus contributes in a significant way to the invasive character of S. pyogenes as previously shown23, but that this locus may also add an additional regulatory circuit based on quorum sensing to the spb operon to compete with endogenous bacteria in the context of non-invasive infections. However, we also suggest that additional regulatory circuits that respond to the in vivo nasopharyngeal environment also control the spb operon independently of sil, and likely other important functions, to allow for the success of S. pyogenes as a globally prominent pathogen.

Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Cloning was carried out in Escherichia coli XL1-Blue (Stratagene) grown on BHI plates supplemented with 1.5% agar, or LB broth. Media was supplemented with erythromycin (150 μg/mL) or ampicillin (100 μg/mL) when required. Recombinant proteins were expressed from E. coli BL21(DE3) at room temperature. S. pyogenes MGAS823229 was grown statically at 37 °C in Todd-Hewitt Yeast (THY) broth, or on solid THY media containing 1.5% agar supplemented with erythromycin (1 μg/mL) and/or tetracycline (0.5 μg/mL), as appropriate. Lactococcus lactis MG136352 was grown statically at 30 °C in M17 medium containing 1% glucose (GM17) and erythromycin was used at 5 μg/mL.

General DNA manipulations

Plasmids and primers used in this work are listed in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Plasmid DNA was isolated using the Qiagen Miniprep Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. Digestions were carried out utilizing restriction enzymes provided by New England Biolabs or Roche following the manufacturer’s instructions. Ligations were performed using T4 DNA Ligase (New England Biolabs). E. coli cells were made competent using the RbCl2 method53.

For transformation of S. pyogenes MGAS8232, an overnight culture was inoculated 1:50 in THY containing 0.6% glycine. Cells were grown for 2 hours and hyaluronidase was added (1 mg/mL). Cells were grown to OD600 of 0.25–0.3 (~3 h). Bacteria were washed once in 15% glycerol, and concentrated 50× in 15% glycerol. Aliquots (200 μL) were stored at −80 °C. DNA (2 μg) was added to room temperature thawed cells in 2 mm electroporation cuvettes, and pulsed with 2100 V and a pulse length of 1.1 ms using the square wave setting (GenePulser, BioRad). Bacteria were transferred to 10 mL THY and recovered at 37 °C. After 2 hours, 1/50 concentration antibiotic was added, and 4 hours later the bacteria were plated on THY agar containing the appropriate antibiotic and grown overnight at 37 °C.

To extract total DNA from S. pyogenes, 2 mL of overnight culture was washed twice with 0.2 mM sodium acetate. The pellet was resuspended in 500 μL Tris EDTA Glucose buffer (10 mM Tris, 2 mM EDTA, 25% glucose) containing 1 mg/mL lysozyme and 50 U mutanolysin and incubated for 1 hour at 37 °C. Cells were pelleted and resuspended in 500 μL lysis buffer (50 mM EDTA, 0.2% SDS) with 40 μg proteinase K and 100 μg RNase, and incubated at 65 °C for 2 hours. Next, 50 μL of 5 M potassium acetate was added to precipitate proteins. The supernatant was mixed with 500 μL ice cold 95% ethanol to precipitate DNA. After one wash with 70% ethanol, DNA was dried and resuspended in 100 μL Qiagen Elution Buffer (EB).

Construction of the loxP-tetR-loxP cassette and integration in the S. pyogenes genome

To identify a neutral site within the MGAS8232 genome for integration of exogenous DNA, we utilized a previous bioinformatic analysis of Rho-independent terminators in Firmicutes16 to locate two opposing genes with separate Rho-independent terminators (pepO and tsf). This location was used to design two regions of ~500-bp flanking this region for homologous recombination of the RIVET cassette into the genome. The downstream recombination site was PCR amplified from the MGAS8232 genome and ligated into the XhoI and ClaI sites of pG+host5. Next, the upstream recombination amplicon was inserted into the XbaI and SacII sites. In order to incorporate the loxP sites, these sequences were included into the ‘outside’ primers. In addition, in an attempt to generate a counter selection system, the human herpes simplex virus-1 thymidine kinase (HSV-tk) gene was codon optimized for S. pyogenes and synthesized by Genscript. This was first cloned into pTRKL2 to fuse the MGAS8232 Gyrase A promoter (PgyrA) to the HSV-tk gene. PgyrA was amplified from MGAS8232 DNA and cloned using BamHI and NcoI while HSV-tk was amplified from pUC57::HSV-tk (Genscript) and cloned using NcoI and XbaI. PgyrA::HSV-tk was cloned into pG+host5 utilizing BamHI and XbaI. Lastly, tetR was amplified from pDG1515 and cloned using BamHI and EcoRV to create the final cassette. Clones were verified with sequencing at each stage and for the final construct. This final construct was designated pCAStet4.

Following electroporation of pCAStet4 into MGAS8232, cells were grown at 30 °C in liquid media for 4 days, replacing media every 24 hours. Next, cells were shifted to 40 °C to prevent plasmid replication, and grown with erythromycin to select for cells that had integrated the plasmid into the chromosome. Cells were grown for an additional 4 days under erythromycin selection changing media every 24 hours, and plated for single colonies. These clones were grown individually, genomic DNA extracted, and PCR was used to ensure integration of the pCAStet4 construct into the chromosome. Once confirmed, clones were grown in liquid culture at 30 °C for 4 days without erythromycin, replacing media every 24 hours. The culture was again plated for single colonies and patched onto plates with and without antibiotics to isolate colonies that have lost the plasmid. Individual clones were then screened by PCR and the correct integration was designated S. pyogenes Cas2.

Generation of the S. pyogenes promoter library and removal of in vitro activated promoters

In order to generate a promoter library driving expression of Cre, we first PCR amplified the cre gene from pSHE11 and cloned the amplicon into the low-copy Gram-positive/E. coli shuttle vector pTRKL2. Next, total genomic DNA from MGAS8232 was digested with increasing concentrations of Sau3AI (0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4 Units of enzyme) for one hour. Digestions were then ligated into the BglII site of pTRKL2::cre. Ligations were transformed into E. coli, and all colonies were scraped off plates, concentrated, and plasmids isolated in toto. Plasmids were then transformed into S. pyogenes Cas2. Cells were grown in liquid medium overnight in the presence of erythromycin and tetracycline for 24 hours to remove in vitro active promoters. The CFU was determined and cells were frozen at −80 °C for further in vivo experiments.

Identification of in vivo induced promoters in S. pyogenes

Animal experiments were performed in accordance with guidelines established by the Canadian Council on Animal Care and approved by the Animal Use Subcommittee at Western University (Protocol #2009–038). Using 108 cells from batches in which in vitro promoters were removed, cells were warmed to room temperature for 30 minutes and inoculated through the nasal route into C57BL/6 mice that express both human HLA-DR4 and HLA-DQ8 mice, as described54. After 48 hours, mice were sacrificed and the complete nasal passages were removed, homogenized and plated. Colonies were enumerated on THY agar containing erythromycin, and patched onto THY agar plates containing tetracycline to screen for the loss of the cassette. Tetracycline sensitive clones were subsequently grown, DNA was extracted and transformed into E. coli to purify plasmids, and inserts sequenced. Homology searches of potential promoter regions were performed using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLASTn) tool from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (http://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov).

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

qRT-PCR analysis of the RIVET cassette integration site, and spbM transcripts from both in vitro and in vivo grown MGAS8232, were determined. For the RIVET cassette, wild-type MGAS8232 and MGAS8232 Cas2 were grown to post-exponential phase. For in vitro grown cells, MGAS8232 was grown in THY broth to an OD600 or ~0.2 or ~0.9 representing early and late exponential phase, respectively. For in vivo grown cells, mice were infected nasally with ~108 CFUs of wild-type MGAS8232 as described above, and the complete nasal turbinates were harvested at 48 h, as described54. Cells from these conditions were resuspended in RNAprotect reagent (Qiagen) and total RNA was prepared using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase and random primers (Invitrogen). PCR reactions were conducted using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad), and performed with the Rotor-Gene Real-Time Analyzer (Corbett Life Science) with primers listed in Table 3. Transcripts were normalized against the expression of the proS or gyrA housekeeping genes55.

Cloning, expression and testing of recombinant Spb peptides

The wild-type spbM and spbN mature coding sequences (described below) were PCR amplified from MGAS8232 chromosomal DNA and individually cloned into the pET32a expression vector (Novagen). The forward primers amplified each spb gene lacking the sequences that encoded the predicted double-glycine type leader peptides. The forward primers were also designed to encode an N-terminal His6 tag, followed by a recognition sequence for the tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease cleavage site (ENLYFQ↓G). The resulting plasmids (pET32a::spbM and pET32a::spbN) generated N-terminal translational fusions with the pET32a thioredoxin tag, a His6 tag, as well as the TEV site for removal of the purification tags. SpbM and SpbN were expressed from E. coli BL21(DE3) at 25 °C following induction with 100 μM IPTG at 30 °C. Recombinant proteins were solubilized in 8 M urea, and refolded using step gradients into 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 200 mM NaCl. N-terminal tags were cleaved with autoinactivation-resistant His7::TEV56. To test for antimicrobial activity, SpbM and SpbN peptides (~1 μg) were spotted into wells punched into agar plates inoculated with indicator strains. The two-peptide nature of the bacteriocin was tested by placing the two peptides at increasing distances on the agar plate to observe for functional complementation.

Cloning and expression of Spb immunity function in Lactococcus lactis

A 489-bp amplicon located immediately downstream of spbN was PCR amplifed from MGAS8232 and cloned into the XmaI and SphI restriction sites of the lactococcal expression plasmid pMG36e to create pMG36e::spbI/RS02360. Plasmids were electroporated into L. lactis MG1363 as described57. In order to test immunity function, recombinant SpbM and SpbN peptides were spotted into a well punched into agar plates inoculated with L. lactis MG1363 containing either pMG36e or pMG36e::spbI/RS02360 and zones of inhibition were visualized.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Armstrong, B. D. et al. Identification of a two-component Class IIb bacteriocin in Streptococcus pyogenes by recombinase-based in vivo expression technology. Sci. Rep. 6, 36233; doi: 10.1038/srep36233 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Walker, M. J. et al. Disease manifestations and pathogenic mechanisms of group A Streptococcus. Clin Microbiol Rev 27, 264–301 (2014).

Carapetis, J. R., Steer, A. C., Mulholland, E. K. & Weber, M. The global burden of group A streptococcal diseases. Lancet Infect Dis 5, 685–694 (2005).

Ralph, A. P. & Carapetis, J. R. Group A streptococcal diseases and their global burden. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 368, 1–27 (2013).

Bessen, D. E. & Lizano, S. Tissue tropisms in group A streptococcal infections. Future Microbiol 5, 623–638 (2010).

Reglinski, M. & Sriskandan, S. The contribution of group A streptococcal virulence determinants to the pathogenesis of sepsis. Virulence 5 (2013).

Tart, A. H., Walker, M. J. & Musser, J. M. New understanding of the group A Streptococcus pathogenesis cycle. Trends Microbiol 15, 318–325 (2007).

Cole, J. N., Barnett, T. C., Nizet, V. & Walker, M. J. Molecular insight into invasive group A streptococcal disease. Nat Rev Microbiol 9, 724–736 (2011).

Camilli, A. & Mekalanos, J. J. Use of recombinase gene fusions to identify Vibrio cholerae genes induced during infection. Mol Microbiol 18, 671–683 (1995).

Abremski, K., Hoess, R. & Sternberg, N. Studies on the properties of P1 site-specific recombination: evidence for topologically unlinked products following recombination. Cell 32, 1301–1311 (1983).

Angelichio, M. J. & Camilli, A. In vivo expression technology. Infect Immun 70, 6518–6523 (2002).

Saviola, B., Woolwine, S. C. & Bishai, W. R. Isolation of acid-inducible genes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with the use of recombinase-based in vivo expression technology. Infect Immun 71, 1379–1388 (2003).

Veal-Carr, W. L. & Stibitz, S. Demonstration of differential virulence gene promoter activation in vivo in Bordetella pertussis using RIVET. Mol Microbiol 55, 788–798 (2005).

Lowe, A. M., Beattie, D. T. & Deresiewicz, R. L. Identification of novel staphylococcal virulence genes by in vivo expression technology. Mol Microbiol 27, 967–976 (1998).

Bron, P. A., Grangette, C., Mercenier, A., de Vos, W. M. & Kleerebezem, M. Identification of Lactobacillus plantarum genes that are induced in the gastrointestinal tract of mice. J Bacteriol 186, 5721–5729 (2004).

Frank, K. L. et al. Use of recombinase-based in vivo expression technology to characterize Enterococcus faecalis gene expression during infection identifies in vivo-expressed antisense RNAs and implicates the protease Eep in pathogenesis. Infect Immun 80, 539–549 (2012).

de Hoon, M. J., Makita, Y., Nakai, K. & Miyano, S. Prediction of transcriptional terminators in Bacillus subtilis and related species. PLoS Comput Biol 1, e25 (2005).

Biswas, I., Gruss, A., Ehrlich, S. D. & Maguin, E. High-efficiency gene inactivation and replacement system for gram-positive bacteria. J Bacteriol 175, 3628–3635 (1993).

Bryan, E. M., Bae, T., Kleerebezem, M. & Dunny, G. M. Improved vectors for nisin-controlled expression in gram-positive bacteria. Plasmid 44, 183–190 (2000).

O’Sullivan, D. J. & Klaenhammer, T. R. High- and low-copy-number Lactococcus shuttle cloning vectors with features for clone screening. Gene 137, 227–231 (1993).

Alam, F. M., Turner, C. E., Smith, K., Wiles, S. & Sriskandan, S. Inactivation of the CovR/S virulence regulator impairs infection in an improved murine model of Streptococcus pyogenes naso-pharyngeal infection. PLoS One 8, e61655 (2013).

Dawid, S., Roche, A. M. & Weiser, J. N. The blp bacteriocins of Streptococcus pneumoniae mediate intraspecies competition both in vitro and in vivo. Infection and immunity 75, 443–451 (2007).

Eran, Y. et al. Transcriptional regulation of the sil locus by the SilCR signalling peptide and its implications on group A Streptococcus virulence. Mol Microbiol 63, 1209–1222 (2007).

Hidalgo-Grass, C. et al. A locus of group A Streptococcus involved in invasive disease and DNA transfer. Mol Microbiol 46, 87–99 (2002).

Nissen-Meyer, J., Oppegard, C., Rogne, P., Haugen, H. S. & Kristiansen, P. E. Structure and Mode-of-Action of the Two-Peptide (Class-IIb) Bacteriocins. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins 2, 52–60 (2010).

van Belkum, M. J., Worobo, R. W. & Stiles, M. E. Double-glycine-type leader peptides direct secretion of bacteriocins by ABC transporters: colicin V secretion in Lactococcus lactis. Mol Microbiol 23, 1293–1301 (1997).

Hidalgo-Grass, C. et al. Effect of a bacterial pheromone peptide on host chemokine degradation in group A streptococcal necrotising soft-tissue infections. Lancet 363, 696–703 (2004).

Wescombe, P. A. et al. Production of the lantibiotic salivaricin A and its variants by oral streptococci and use of a specific induction assay to detect their presence in human saliva. Appl Environ Microbiol 72, 1459–1466 (2006).

Wescombe, P. A. & Tagg, J. R. Purification and characterization of streptin, a type A1 lantibiotic produced by Streptococcus pyogenes. Appl Environ Microbiol 69, 2737–2747 (2003).

Smoot, J. C. et al. Genome sequence and comparative microarray analysis of serotype M18 group A Streptococcus strains associated with acute rheumatic fever outbreaks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99, 4668–4673 (2002).

Tagg, J. R. & Bannister, L. V. “Fingerprinting” beta-haemolytic streptococci by their production of and sensitivity to bacteriocine-like inhibitors. J Med Microbiol 12, 397–411 (1979).

van de Guchte, M., van der Vossen, J. M., Kok, J. & Venema, G. Construction of a lactococcal expression vector: expression of hen egg white lysozyme in Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol 55, 224–228 (1989).

Bessen, D. E. Population biology of the human restricted pathogen, Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect Genet Evol 9, 581–593 (2009).

Klaenhammer, T. R. Genetics of bacteriocins produced by lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev 12, 39–85 (1993).

Corr, S. C. et al. Bacteriocin production as a mechanism for the antiinfective activity of Lactobacillus salivarius UCC118. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104, 7617–7621 (2007).

Bogaert, D. et al. Variability and diversity of nasopharyngeal microbiota in children: a metagenomic analysis. PLoS One 6, e17035 (2011).

Walls, T., Power, D. & Tagg, J. Bacteriocin-like inhibitory substance (BLIS) production by the normal flora of the nasopharynx: potential to protect against otitis media? J Med Microbiol 52, 829–833 (2003).

Fiedler, T. et al. Protective mechanisms of respiratory tract Streptococci against Streptococcus pyogenes biofilm formation and epithelial cell infection. Appl Environ Microbiol 79, 1265–1276 (2013).

Plainvert, C. et al. Molecular epidemiology of sil locus in clinical Streptococcus pyogenes strains. J Clin Microbiol 52, 2003–2010 (2014).

Ferretti, J. J. et al. Complete genome sequence of an M1 strain of Streptococcus pyogenes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 98, 4658–4663 (2001).

Sumby, P. et al. Evolutionary origin and emergence of a highly successful clone of serotype M1 group a Streptococcus involved multiple horizontal gene transfer events. The Journal of infectious diseases 192, 771–782 (2005).

Miyoshi-Akiyama, T., Watanabe, S. & Kirikae, T. Complete genome sequence of Streptococcus pyogenes M1 476, isolated from a patient with streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. J Bacteriol 194, 5466 (2012).

Belotserkovsky, I. et al. Functional analysis of the quorum-sensing streptococcal invasion locus (sil). PLoS Pathog 5, e1000651 (2009).

Venema, K. et al. Functional analysis of the pediocin operon of Pediococcus acidilactici PAC1.0: PedB is the immunity protein and PedD is the precursor processing enzyme. Mol Microbiol 17, 515–522 (1995).

Quadri, L. E., Yan, L. Z., Stiles, M. E. & Vederas, J. C. Effect of amino acid substitutions on the activity of carnobacteriocin B2. Overproduction of the antimicrobial peptide, its engineered variants, and its precursor in Escherichia coli. The Journal of biological chemistry 272, 3384–3388 (1997).

Havarstein, L. S., Diep, D. B. & Nes, I. F. A family of bacteriocin ABC transporters carry out proteolytic processing of their substrates concomitant with export. Mol Microbiol 16, 229–240 (1995).

Rawlings, N. D., Barrett, A. J. & Finn, R. Twenty years of the MEROPS database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors. Nucleic Acids Res 44, D343–D350 (2016).

Franke, C. M., Tiemersma, J., Venema, G. & Kok, J. Membrane topology of the lactococcal bacteriocin ATP-binding cassette transporter protein LcnC. Involvement of LcnC in lactococcin a maturation. The Journal of biological chemistry 274, 8484–8490 (1999).

Pal, G. & Srivastava, S. In vitro activity of a recombinant ABC transporter protein in the processing of plantaricin E pre-peptide. Arch Microbiol 197, 843–849 (2015).

Lloubes, R., Bernadac, A., Houot, L. & Pommier, S. Non classical secretion systems. Research in microbiology 164, 655–663 (2013).

Kizy, A. E. & Neely, M. N. First Streptococcus pyogenes signature-tagged mutagenesis screen identifies novel virulence determinants. Infect Immun 77, 1854–1865 (2009).

Baruch, M. et al. An extracellular bacterial pathogen modulates host metabolism to regulate its own sensing and proliferation. Cell 156, 97–108 (2014).

Wegmann, U. et al. Complete genome sequence of the prototype lactic acid bacterium Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363. J Bacteriol 189, 3256–3270 (2007).

Sambrook, J. & Russell, D. W. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 3rd edn (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N. Y., 2001).

Kasper, K. J. et al. Bacterial superantigens promote acute nasopharyngeal infection by Streptococcus pyogenes in a human MHC Class II-dependent manner. PLoS Pathog 10, e1004155 (2014).

Smoot, J. C., Korgenski, E. K., Daly, J. A., Veasy, L. G. & Musser, J. M. Molecular analysis of group A Streptococcus type emm18 isolates temporally associated with acute rheumatic fever outbreaks in Salt Lake City, Utah. J Clin Microbiol 40, 1805–1810 (2002).

Kapust, R. B. et al. Tobacco etch virus protease: mechanism of autolysis and rational design of stable mutants with wild-type catalytic proficiency. Protein Eng 14, 993–1000 (2001).

Holo, H. & Nes, I. F. High-Frequency Transformation, by Electroporation, of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris Grown with Glycine in Osmotically Stabilized Media. Appl Environ Microbiol 55, 3119–3123 (1989).

Guerout-Fleury, A. M., Shazand, K., Frandsen, N. & Stragier, P. Antibiotic-resistance cassettes for Bacillus subtilis. Gene 167, 335–336 (1995).

Acknowledgements

We thank Katherine Kasper for assistance with the mouse nasal infection experiments and Catherine Kerr for constructing the pMSP3535::cre-forward and pMSP3535::cre-reverse plasmids, as well as other members of the McCormick laboratory for helpful discussions. We also thank Jeremy Burton (Lawson Health Research Institute) for providing bacteriocin indictor strains, Gary Dunny (University of Minnesota) for providing pMSP3535, Todd Klaenhammer (North Carolina State University) for providing pTRKL2, and Paul Sadowsky (University of Toronto) for providing the cre containing plasmid pSHE11. This work was funded by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery grant to J.K.M.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.D.A., C.A.H., N.C.T., A.T.W., J.J.Z. and J.K.M. designed the study and conducted the experiments. B.D.A. and J.K.M. wrote the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Armstrong, B., Herfst, C., Tonial, N. et al. Identification of a two-component Class IIb bacteriocin in Streptococcus pyogenes by recombinase-based in vivo expression technology. Sci Rep 6, 36233 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36233

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36233

This article is cited by

-

Identification and Characterization of a Two-Peptide Class IIb Bacteriocin in Streptococcus pluranimalium Isolated from the Nasal Cavity of a Healthy Pig

Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.