Abstract

A series of novel optically active [5]helicene-derived phosphine ligands (L1, with a 7,8-dihydro[5]helicene core structure- and L2, with a fully aromatic [5]helicene core structure) were synthesized. Despite their structural similarities, L1 and L2 exhibit particularly different characteristics in their use as chiral ligands. L1 was highly effective in the asymmetric allylation of indoles with 1,3-diphenylallyl acetate (up to 99% ee), and in the etherification of alcohols (up to 96% ee). In contrast, L2 was highly effective in the stereocontrol of helical chirality in Suzuki–Miyaura coupling (SMC) reaction (up to 99% ee). Density functional theory analysis was employed to propose a model that accounts for the origin of the enantioselectivity in these reactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rational design and development of new chiral ligands to enable stereocontrol in a wide variety of reactions is one of the most important topics in modern organic synthesis1,2. To date, chiral ligands containing heteroatoms with strong σ-donating properties, such as phosphorus and nitrogen have been commonly utilized in transition-metal-catalyzed asymmetric reactions. In addition, chiral ligands containing π-donating alkenes and arenes have attracted increasing attention in recent years3,4,5,6. More recently, the combination of these two features, i.e., the development of hybrid ligands containing both σ-donating and π-donating groups, has received growing attention, and unprecedented reactivity and stereoselectivity have been observed (Fig. 1a)7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. Thus, to develop novel and efficient hybrid chiral ligands, we envisage that helicene would be a suitable π-donating group to efficiently construct a helical environment around a metal center (Fig. 1b).

Helicenes are nonplanar screw-shaped polycyclic compounds based on ortho-condensed benzene or other aromatic rings, which exhibit unique structural, optical, and electronic features. Thus, helicenes can be utilized them a broad range of applications in chiral materials, in the chiral recognition of biomolecules, and in asymmetric synthesis16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. More specifically, chiral helicene-based trivalent phosphorus ligands are efficient asymmetric inductors in metal-catalyzed asymmetric reactions and show good to excellent enantioselectivities25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33. We hypothesized that novel helicenylphosphine ligands, which induce intramolecular metal-arene interactions, could be used to construct an efficient chiral catalytic system. To realize this concept, we designed two types of [5]helicene-derived phosphine ligands (L1, with a 7,8-dihydro[5]helicene core structure; and L2, with a fully aromatic [5]helicene core structure) as rationally simplified molecules (Fig. 1b). Unlike typical [5]helicenes that are conformationally unstable and tend to racemize34,35, L1 and L2 are expected to exhibit stable chirality, as helix inversion is prevented by steric hindrance from the phosphine group at the C1 position36,37,38. Furthermore, the helicene backbones in these ligands may affect the electronic structures of the chelating substrate around the metal, due to different helical pitches and conformational flexibility.

Results and Discussion

Syntheses and structural characterization of L1 and L2

Ligands L1 and L2 were synthesized via the route outlined in Fig. 2a. The Suzuki–Miyaura coupling (SMC) of 4-chloro-3-formy-l,2-dihydrophenanthrene 3 with 2-bromophenylboronic acid 4 was achieved in a chemoselective manner to give coupling product 5 in 89% yield37. Subsequent Ohira–Bestmann modification of the Seyferth–Gilbert homologation followed by cycloisomerization with 10 mol% PtCl2 resulted in the formation of (±)-1-bromo-7,8-dihydro[5]helicene rac-6 (54% yield over two steps). Lithiation of rac-6 and subsequent reaction with chlorodiphenylphosphine and treatment with hydrogen peroxide afforded the (±)-phosphine oxide (rac-7) in 63% yield. The optical resolution of rac-7 was successfully achieved by application of the Keglevich procedure using spiro-TADDOL (−)-8 as a resolving agent39 to afford optically pure (P)-7. Enantiomer (M)-7 could also be prepared using (+)-8 (see Supplementary Information). Phosphine oxide (P)-7 was converted into the desired L1 using trichlorosilane and P(OEt)3 in 72% yield, while ligand L2 was prepared in 70% yield over two steps by the oxidative aromatization of (P)-7 with 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone (DDQ), and subsequent reduction of (P)-9.

(a) Preparation of chiral phosphines L1 and L2. (b) ECD spectra of (P)-L1 (red solid line), (M)-L1 (red dashed line), (P)-L2 (blue solid line), and (M)-L2 (blue dashed line) in acetonitrile (1.0 × 10−5 M). (c) Calculated (CAM-B3LYP/6-31 + G**//B97-D/6-31G*) ECD spectra of (P)-L1 (red solid line) and (P)-L2 (blue solid line).

To determine the absolute configuration of the resolved enantiomers of L1 and L2, electronic circular dichroism (ECD) spectroscopy was carried out to give the spectra shown in Fig. 2b. In all cases (within experimental errors), mirror-image plots were displayed for the (+) and (−) enantiomers. The ECD spectrum of (+)-L2 showed two bands with a first positive band at ~325 nm and a second negative band at ~280 nm, indicating P helicity (opposite signs were observed for M helicity). These results are in agreement with the absolute configurations previously reported for 1-funcionalized [5]helicenes37. We also calculated the ECD spectra of (P)-L1 and -L2 to compare them with the experimental ECD spectra (Fig. 2c). The ligand structures were optimized using the B97-D/6-31G* level of theory, and the ECD spectra were calculated using the time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT) method at the CAM-B3LYP/6-31 + G** level of theory with SMD acetonitrile solvation. Indeed, in the calculated spectra, cotton effects were observed at >200 nm, with intensity patterns similar to those experimentally observed for (P)-L1 and -L2.

The structures of L1 and L2 were confirmed by X-ray crystallography (Fig. 3). Based on the obtained structures of L1 and L2, the helical pitch diameter of L1 (3.54–3.50 Å) is longer than that of L2 (3.39–3.34 Å). To obtain further information regarding the phosphine-metal-arene interaction of the metal complex of L1, we prepared Pd(dba)[L1] complex 10 from Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3 and L1. As expected, results from X-ray crystallography showed that the double bond (C8a–C14b) of the helicene ligand was coordinated with the palladium center in a side-on (η2) fashion.

Pd-Catalyzed asymmetric allylic substitutions

With the phosphine ligands in hand, we investigated their effectiveness in Pd-catalyzed asymmetric allylic substitution reactions, as the mechanism of these reactions is fairly well understood40,41,42. As a model reaction, we studied the alkylation of racemic 1,3-diphenylallyl acetate 11 with dimethyl malonate, using Cs2CO3 as the base and [PdCl(C3H5)]2 (0.5 mol%) as the palladium source, in the presence of a catalytic amount of L1 or L2 (1 mol%) in CH2Cl2 at room temperature (Fig. 4a). Ligand (M)-L1 was highly effective in this reaction, affording (S)-12 in 99% yield with 94% ee, while (M)-L2 afforded (S)-12 in 99% yield with only 71% ee.

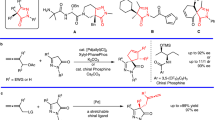

Encouraged by the promising results obtained with L1, the asymmetric allylation of indoles using 11 was subsequently investigated. In contrast to commonly studied nucleophiles, the Pd-catalyzed asymmetric allylation of indoles has been met with very limited success10,43. As shown in Fig. 4b, all reactions of indoles bearing substituents on the 2-, 3-, 5-, and 7-positions proceeded efficiently to give the desired products (13a-g) in excellent yields (95–99%) and enantioselectivities (96–99%) under optimized reaction conditions (see Table S1, Supplementary Information). To the best of our knowledge, this is the most efficient catalytic asymmetric allylation of indoles with 11 reported to date. L1 was also effective in the Pd-catalyzed allylic etherification of alcohols to give the desired products (14a-e) in high yields (61–95%) and enantioselectivities (84–96%, Fig. 4c).

To elucidate the stereoselectivity of the exo and endo (π-allyl)palladium intermediates (IM-exo and IM-endo), DFT calculations using the B3PW91/6-31G* level of theory (LANL2DZ for the Pd atoms) were performed for geometry optimization. Figure 5 shows their calculated structures and relative energies of formation, with IM-endo being the most stable based on these calculations. Indeed, the IM-endo intermediate is favored because of the reduced steric repulsion between the helicene backbone and the allylic group. Assuming that nucleophilic attack on the allyl complex takes place at the allylic carbon atom (C3) due to the larger trans effect of phosphorus44, IM-endo affords products with S configuration. This is clearly reflected in the computed lower natural bond orbital (NBO)-charge of the C3 position.

Pd-Catalyzed asymmetric SMC

We then investigated the performance of L1 and L2 in the asymmetric SMC reaction45,46,47,48,49,50,51 between diisopropyl (1-bromonaphthalen-2-yl) phosphonate 15a and o-tolylboronic acid 16a under optimized reaction conditions (Pd(OAc)2/L*/toluene/50 °C, see Table S3, Supplementary Information). As shown in Fig. 6, in contrast to the results obtained with (P)-L1 (87% yield, 81% ee), the use of (P)-L2 gave product (R)-17aa in excellent yield and enantioselectivity (97% yield, 95% ee). We then moved on to further examine the substrate scope of this reaction. A coupling reaction between phosphonates 15a-d and o-tolylboronic acid 16a gave the corresponding axially chiral biaryls (17aa–17da) in excellent yields and moderate to high ee values (Fig. 6). These results demonstrate that the steric and electronic effects of substituents on the arylboronic acids 16b-f affected the reactivities and enantioselectivities. More specifically, the introduction of an ethyl group at the C2-position of the phenyl ring increased the enantioselectivity (99% ee for 17af). This confirmed that L2 afforded improved enantioselectivity over L1 (for full details, see Table S4, Supplementary Information).

It was reported that the stereoselectivity of the SMC reaction is induced by reductive elimination from Pd(II)46,47. Thus, to gain an insight into the factors determining the enantioselectivity in our novel system, DFT calculations for the reductive elimination of Pd ((P)-L1) and Pd((P)-L2) complexes providing 17ba were performed using the B97-D/6-31G* level of theory (LANL2DZ for the Pd atom). As shown in Fig. 7a, we hypothesized that four geometrical isomers (IM1-A–D) could be formed after oxidative addition. As the arene substrate and phosphorus center bearing strong trans influences prefer the cis arrangement, we surveyed the transition states (TSs) for the reductive elimination steps of IM2-Aanti, IM2-Asyn, IM2-Bsyn, and IM2-Banti, derived from IM1-A and IM1-B.

Using ligands L1 and L2, we optimized seven (for L1) and six (for L2) of the eight possible transition state structures and their energies were calculated as shown in Fig. 7a. Among these, TS6 and TS7 were the most stable for (S)-17ba and (R)-17ba, respectively. The energy gap between TS6 and TS7 could arise from differences in the hydrogen bonding partners of the phosphonate sp2-oxygen and the hydrogen atom on the tolyl group (Fig. 7b; for all calculated transition state structures, see Figs S1 and S2, Supplementary Information). TS7 would therefore be energetically favorable because C(sp2)-H is a better hydrogen donor than C(sp3)-H48,52. In addition, we found a significant energy difference between TS6 and TS7 (ΔGrel = 0.9 kcal mol−1 for L1, ΔGrel = 2.1 kcal mol−1 for L2). Since in the transition states, the average helical pitch of L2 (3.44 ± 0.06 Å) is smaller than that of L1 (3.52 ± 0.10 Å), additional CH/π interactions can form between the arene moiety and the helical aromatic framework (Fig. 7b), reflecting the high enantioselectivity of coupling product 17ba. The Boltzmann distributions of all optimized transition structures using (P)-L1 and (P)-L2 as ligands predicted (R)-product formation with selectivities of 62% ee and 91% ee, respectively. These values correlated well with the experimental results.

In summary, two novel optically active [5]helicenylphosphine ligands (L1, with a 7,8-dihydro[5]helicene core structure, and L2, with a fully aromatic [5]helicene core structure) were successfully synthesized, and the ligand structures were determined using X-ray crystallography. As expected, the X-ray crystallographic analysis of the Pd(dba)[L1] complex unambiguously showed that both the phosphorus atom and the double bond of the ligand are coordinated to the Pd center. These ligands were applied in Pd-catalyzed asymmetric allylic substitutions and Suzuki–Miyaura coupling (SMC) reactions. The newly developed ligands, in particular L1, were highly effective in asymmetric allylic substitutions. Moreover, we demonstrated that L2 serves as a highly enantioselective ligand in the asymmetric SMC reaction to yield axially chiral biaryl compounds. Our concept may therefore open a novel route toward the application of helicene-based phosphine ligands in Pd-catalyzed asymmetric reactions.

Methods

General procedure for the Pd-catalyzed asymmetric allylic alkylation of indole

An oven-dried screw-capped vessel was charged with [PdCl(C3H5)]2 (0.5 mol%), L1 (1.0 mol%), and CH2Cl2 (0.30 mL) under argon. The resulting mixture was stirred for 30 min at room temperature. Racemic 1,3-diphenyl-2-propenyl acetate 11 (0.15 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (0.45 mL), Cs2CO3 (0.3 mmol), and the corresponding indole (0.3 mmol) were added subsequently, and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature until all starting material had been consumed. The reaction mixture was then diluted with CH2Cl2, washed with water and brine, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel eluting with hexane–EtOAc (95:5) to afford 13. The absolute configuration was determined by comparing the specific optical rotations with literature data (see Supplementary Information).

General procedure for the Pd-catalyzed asymmetric allylic etherification

An oven-dried screw-capped vessel was charged with [PdCl(C3H5)]2 (0.5 mol%), L1 (1.0 mol%), and CH2Cl2 (0.30 mL) under argon. The resulting mixture was stirred for 30 min at room temperature. Racemic 1,3-diphenyl-2-propenyl acetate 11 (0.15 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (0.45 mL), Cs2CO3 (0.45 mmol), and the corresponding alcohol (0.45 mmol) were added subsequently, and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature until all starting material had been consumed. The reaction mixture was then diluted with diethyl ether, washed with water and brine, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel eluting with hexane–EtOAc to afford 14. The absolute configuration was determined by comparing the specific optical rotations with literature data (see Supplementary Information).

General procedure for the Pd-catalyzed asymmetric SMC

An oven-dried amber screw-capped vessel was charged with Pd(OAc)2 (2.0 mol%), L2 (2.4 mol%), aryl halide 15 (0.1 mmol), phenylboronic acid 16 (0.2 mmol), and K3PO4 (0.3 mmol). The vessel was then filled with argon gas. Subsequently, degassed toluene (0.5 mL) was added to the vessel and the reaction mixture was stirred at 50 °C until all starting material had been consumed. After cooling to room temperature, the reaction mixture was diluted with EtOAc, washed with water and brine, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel eluting with hexane–EtOAc to give a mixture of 17 and dehalogenated-15. The yields were determined by 1H NMR analysis. The absolute configurations of 17aa and 17ba were determined by comparing the specific optical rotations with literature data (see Supplementary Information). The absolute configurations of other products were not determined.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Yamamoto, K. et al. Rational Design and Synthesis of [5]Helicene-Derived Phosphine Ligands and Their Application in Pd-Catalyzed Asymmetric Reactions. Sci. Rep. 6, 36211; doi: 10.1038/srep36211 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Yoon, T. P. & Jacobsen, E. N. Privileged chiral catalysts. Science 299, 1691–1693 (2003).

Zhou, Q.-L. Privileged chiral ligands and catalysts. (Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2011).

Glorius, F. Chiral olefin ligands-new “spectators” in asymmetric catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43, 3364–3366 (2004).

Johnson, J. B. & Rovis, T. More than bystanders: the effect of olefins on transition-metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 840–871 (2008).

Defieber, C., Grützmacher, H. & Carreira, E. M. Chiral olefins as steering ligands in asymmetric catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 4482–4502 (2008).

Shintani, R. & Hayashi, T. Chiral diene ligands for asymmetric catalysis. Aldrichim. Acta. 42, 31–38 (2009).

Maire, P. et al. Olefins as steering ligands for homogeneously catalyzed hydrogenations. Chem. Eur. J. 10, 4198–4205 (2004).

Shintani, R., Duan, W.-L., Nagano, T., Okada, A. & Hayashi, T. Chiral phosphine-olefin bidentate ligands in asymmetric catalysis: rhodium-catalyzed asymmetric 1,4-addition of aryl boronic acids to maleimides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 4611–4614 (2005).

Liu, Z. & Du, H. Development of chiral terminal-alkene-phosphine hybrid ligands for palladium-catalyzed asymmetric allylic substitutions. Org. Lett. 12, 3054–3057 (2010).

Cao, Z. et al. Pd-catalyzed asymmetric allylic alkylation of indoles and pyrroles by chiral alkene-phosphine ligands. Org. Lett. 13, 2164–2167 (2011).

Kočovský, P. et al. Palladium(II) complexes of 2-dimethylamino-2′-diphenylphosphino-1,1′-binaphthyl (MAP) with unique P,Cσ -coordination and their catalytic activity in allylic substitution, Hartwig–Buchwald amination, and Suzuki Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 7714–7715 (1999).

Barder, T. E., Walker, S. D., Martinelli, J. R. & Buchwald, S. L. Catalysts for Suzuki–Miyaura coupling processes: scope and studies of the effect of ligand structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 4685–4696 (2005).

Pratap, R., Parrish, D., Gunda, P., Venkataraman, D. & Lakshman, M. K. Influence of biaryl phosphine structure on C-N and C-C bond formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 12240–12249 (2009).

Huang, Z. et al. Weak arene C-H···O hydrogen bonding in palladium-catalyzed arylation and vinylation of lactones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 5807–5812 (2013).

Pregosin, P. S. 31P and 13C NMR studies on metal complexes of phosphorus-donors: Recognizing surprises. Coord. Chem. Rev. 252, 2156–2170 (2008).

Shen, Y. & Chen, C.-F. Helicenes: synthesis and applications. Chem. Rev. 112, 1463–1535 (2012).

Gingras, M. One hundred years of helicene chemistry. Part 1: non-stereoselective syntheses of carbohelicenes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 968–1006 (2013).

Gingras, M., Felix, G. & Peresutti, R. One hundred years of helicene chemistry. Part 2: stereoselective syntheses and chiral separations of carbohelicenes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 1007–1050 (2013).

Gingras, M. One hundred years of helicene chemistry. Part 3: applications and properties of carbohelicenes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 1051–1095 (2013).

Urbano, A. Recent developments in the synthesis of helicene-like molecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 42, 3986–3989 (2003).

Katz, T. J. Syntheses of functionalized and aggregating helical conjugated molecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 39, 1921–1923 (2000).

Bosson, J., Gouin, J. & Lacour, J. Cationic triangulenes and helicenes: synthesis, chemical stability, optical properties and extended applications of these unusual dyes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 2824–2840 (2014).

Aillard, P., Voituriez, A. & Marinetti, A. Helicene-like chiral auxiliaries in asymmetric catalysis. Dalt. Trans. 43, 15263–15278 (2014).

Narcis, M. J. & Takenaka, N. Helical-chiral small molecules in asymmetric catalysis. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 21–34 (2014).

Virieux, D., Sevrain, N., Ayad, T. & Pirat, J.-L. Chapter two–helical phosphorus derivatives: synthesis and applications. Adv. Heterocycl. Chem. 116, 37–83 (2015).

Saleh, N., Shen, C. & Crassous, J. Helicene-based transition metal complexes: synthesis, properties and applications. Chem. Sci. 5, 3680–3694 (2014).

Reetz, M. T., Beuttenmüller, E. W. & Goddard, R. First enantioselective catalysis using a helical diphosphane. Tetrahedron Lett. 38, 3211–3214 (1997).

Yavari, K. et al. Helicenes with embedded phosphole units in enantioselective gold catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 861–865 (2014).

Krausová, Z. et al. Helicene-based phosphite ligands in asymmetric transition-metal catalysis: exploring Rh-catalyzed hydroformylation and Ir-catalyzed allylic amination. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 3849–3857 (2011).

Monteforte, M. et al. Tetrathiaheterohelicene phosphanes as helical-shaped chiral ligands for catalysis. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 5649–5658 (2011).

Aillard, P. et al. Phosphathiahelicenes: Synthesis and uses in enantioselective gold catalysis. Chem. Eur. J. 20, 12373–12376 (2014).

Nakano, D. & Yamaguchi, M. Enantioselective hydrogenation of itaconate using rhodium bihelicenol phosphite complex. Matched/mismatched phenomena between helical and axial chirality. Tetrahedron Lett. 44, 4969–4971 (2003).

Tsujihara, T. et al. Nickel-Catalyzed Construction of Chiral 1-[6]Helicenols and Application in the Synthesis of [6]Helicene-Based Phosphinite Ligands. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 4948–4952 (2016).

Martin, R. H. & Marchant, M.-J. Thermal racemisation of [6], [7], [8] and [9] helicene. Tetrahedron Lett. 13, 3707–3708 (1972).

Martin, R. H. & Marchant, M. J. Thermal racemisation of hepta-, octa-, and nonahelicene: Kinetic results, reaction path and experimental proofs that the racemisation of hexa- and heptahelicene does not involve an intramolecular double Diels-Alder reaction. Tetrahedron 30, 347–349 (1974).

Scherübl, H., Fritzsche, U. & Mannschreck, A. Liquid chromatography on triacetylcellulose, 6. synthesis, chromatographic enrichment of enantiomers, and barriers to enantiomerization of helical phenanthrenes. Chem. Ber. 117, 336–343 (1984).

Yamamoto, K., Okazumi, M., Suemune, H. & Usui, K. Synthesis of [5]helicenes with a substituent exclusively on the interior side of the helix by metal-catalyzed cycloisomerization. Org. Lett. 15, 1806–1809 (2013).

Usui, K. et al. Synthesis and resolution of substituted [5]carbohelicenes. J. Org. Chem. 80, 6502–6508 (2015).

Bagi, P. et al. Resolution of 1-n-butyl-3-methyl-3-phospholene 1-oxide with TADDOL derivatives and calcium salts of O,O’-dibenzoyl-(2R,3R)-or O,O’-di-p-toluoyl-(2R,3R)-tartaric acid. Chirality 26, 174–182 (2014).

Trost, B. M. & Crawley, M. L. Asymmetric transition-metal-catalyzed allylic alkylations: applications in total synthesis. Chem. Rev. 103, 2921–2944 (2003).

Lu, Z. & Ma, S. Metal-catalyzed enantioselective allylation in asymmetric synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 258–297 (2008).

Trost, B. M., Zhang, T. & Sieber, J. D. Catalytic asymmetric allylic alkylation employing heteroatom nucleophiles: a powerful method for C-X bond formation. Chem. Sci. 1, 427–440 (2010).

Cheung, H. Y. et al. Enantioselective Pd-catalyzed allylic alkylation of indoles by a new class of chiral ferrocenyl P/S ligands. Org. Lett. 9, 4295–4298 (2007).

Constantine, R. N., Kim, N. & Bunt, R. C. Hammett studies of enantiocontrol by PHOX ligands in Pd-catalyzed allylic substitution reactions. Org. Lett. 5, 2279–2282 (2003).

Zhang, D. & Wang, Q. Palladium catalyzed asymmetric Suzuki–Miyaura coupling reactions to axially chiral biaryl compounds: Chiral ligands and recent advances. Coord. Chem. Rev. 286, 1–16 (2015).

Cammidge, A. N. & Crepy, K. V. L. The first asymmetric Suzuki cross-coupling reaction. Chem. Commun. 1723–1724 (2000).

Yin, J. & Buchwald, S. L. A catalytic asymmetric Suzuki coupling for the synthesis of axially chiral biaryl compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 12051–12052 (2000).

Shen, X., Jones, G. O., Watson, D. A., Bhayana, B. & Buchwald, S. L. Enantioselective synthesis of axially chiral biaryls by the Pd-catalyzed Suzuki-Miyaura reaction: substrate scope and quantum mechanical investigations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 11278–11287 (2010).

Xu, G., Fu, W., Liu, G., Senanayake, C. H. & Tang, W. Efficient syntheses of korupensamines A, B and michellamine B by asymmetric Suzuki-Miyaura coupling reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 570–573 (2014).

Zhou, Y. et al. Enantioselective synthesis of axially chiral biaryl monophosphine oxides via direct asymmetric Suzuki Coupling and DFT investigations of the enantioselectivity. ACS Catal. 4, 1390–1397 (2014).

Yamamoto, T., Akai, Y., Nagata, Y. & Suginome, M. Highly enantioselective synthesis of axially chiral biarylphosphonates: asymmetric Suzuki-Miyaura coupling using high-molecular-weight, helically chiral polyquinoxaline-based phosphines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 8844–8847 (2011).

Allerhand, A. & Von Rague Schleyer, P. A survey of C-H groups as proton donors in hydrogen bonding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 85, 1715–1723 (1963).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grants (16K18846, 25410096), and the Cooperative Research Program of the “Network Joint Research Center for Materials and Devices”. K.Y. acknowledges support from a JSPS research fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.Y., T.S. and K.U. performed the chemical synthesis and characterized the compounds. K.I. conducted the X-ray crystallographic analysis. K.U. performed computational studies. K.T., G.H., H.S. and K.U. performed data analysis and wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Yamamoto, K., Shimizu, T., Igawa, K. et al. Rational Design and Synthesis of [5]Helicene-Derived Phosphine Ligands and Their Application in Pd-Catalyzed Asymmetric Reactions. Sci Rep 6, 36211 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36211

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36211

This article is cited by

-

Synthesis, photophysical and chiroptical properties of 9–cyano[7]helicene for OLED applications. A combined experimental and theoretical investigation

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2024)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.