Abstract

As an important precursor and derivate of graphene, graphene oxide (GO) has received wide attention in recent years. However, the synthesis of GO in an economical and efficient way remains a great challenge. Here we reported an improved NaNO3-free Hummers method by partly replacing KMnO4 with K2FeO4 and controlling the amount of concentrated sulfuric acid. As compared to the existing NaNO3-free Hummers methods, this improved routine greatly reduces the reactant consumption while keeps a high yield. The obtained GO was characterized by various techniques, and its derived graphene aerogel was demonstrated as high-performance supercapacitor electrodes. This improved synthesis shows good prospects for scalable production and applications of GO and its derivatives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Graphene1, a single layer of carbon atoms bonded into a honeycomb two-dimensional lattice, has attracted great interests from scientists and engineers because of its extraordinary properties and wide applications2,3, such as functional films, electric devices and energy storage devices (Li-ion batteries, supercapacitors) etc. Different from graphene, which is almost not soluble and cannot be dispersed in water or any organic solvent3,4, graphene oxide (GO) contains high-density oxygen functional groups, like hydroxyl and epoxy group on its basal plane, and carboxyl at its edge4,5. They afford GO with excellent water solubility, ease of functionalization and convenience in processing etc.6,8, making it the most popular precursor of graphene. Undoubtedly, it is of great significance to develop economical, eco-friendly and scalable routines to produce GO3,9,10.

As is well known, GO is synthesized dominantly via chemical oxidation of natural graphite even though there are a few reports on alternative electrochemical oxidation11,12. Back to 185913, Brodie first synthesized graphite oxide by adding potassium chlorate to the slurry of graphite in fuming nitric acid. After about 40 years, Staudenmaier14 improved this method by replacing about two thirds of fuming HNO3 with concentrated H2SO4 and feeding the chlorate in batches. Based on these work, Hummers and Offeman15 developed an alternate oxidation method in 1958, often called Hummers method, in which NaNO3 and KMnO4 dissolved in concentrated H2SO4 was used to oxidize graphite into graphite oxide within a few hours. Thanks to the ease and short time of execution, Hummers’ method was widely adopted to afford GO2,3,16,17, but it still suffers from several flaws18,19,20,21,22,23,24, including toxic gas generation (NO2, N2O4), residual nitrate and low yield etc. To address these problems, various modification on Hummers’ method have been made in the past 20 years, and the main strategies can be summarized as follows: first18,19, removing NaNO3 directly from Hummers method with an improved workup; second20,21, adding a step of preoxidation before KMnO4 oxidation (in the absence of NaNO3); third22,23,24, increasing the amount of KMnO4 instead of NaNO3; fourth25,26,27, replacing KMnO4 with K2FeO4 while NaNO3 was removed. For example, in the report of Kovtyukhova et al.20, graphite was preoxidized by K2S2O8 and P2O5 before Hummers’ procedure was implemented. This work resulted in highly oxidized GO, but the whole process which contains solution transfer and material drying is rather time-consuming. By increasing the amount of both KMnO4 and concentrated H2SO4 (containing 1/9 H3PO4) instead of NaNO3, Marcano et al.22 found that the improved Hummers method leads to higher yield and the temperature can be easily controlled. Recently, Gao et al.25,26 reported a K2FeO4-based oxidation approach instead of KMnO4, and obtained single-layer GO at room temperature.

Despite the above progresses, two problems remain in various modified versions of Hummers method: (1) high consumption of the oxidants and intercalating agents was inevitable, (2) most of the synthesis routines proceed for a long time, both of which result in high cost and poor scalability in practical applications19,28. Therefore, there is a strong demand to develop an economical and efficient method for the synthesis of GO. In the present paper, we made a further improvement for NaNO3-free Hummers methods by partly replacing KMnO4 with K2FeO4 and reducing the amount of concentrated sulfuric acid. It shows that GO can be synthesized successfully with rather low auxiliary agents-to-graphite ratio within shorter reaction duration. The resultant GO was characterized by various instrumental methods, and an example of application was given for the GO derived graphene aerogel (GA) as supercapacitor electrodes. The present work provides a new possibility for the production of GO in an economical, eco-friendly and efficient way.

Results

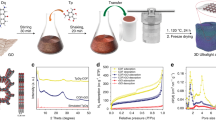

GO was prepared from natural flake graphite through one-pot synthesis based on new modified Hummers method. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the synthesis process consists of three critical steps15,29,30: (I) H2SO4 intercalation and boric acid stabilized31 K2FeO4/KMnO4 preoxidation at low temperature, during which H2SO4-graphite intercalation compounds (GIC)32 and then initial pristine graphite oxide (PGO)9 form, (II) deep oxidation with secondary feeding of KMnO4 at middle temperature, when GIC convert entirely into PGO by the diffusion-controlling oxidation9, and (III) hydrolysis and exfoliation of PGO into GO after the addition of H2O. The obtained GO was named GO2, while for comparison, another GO coined as GO1 was synthesized by Kovtyukhova improved method20. Further, GA was hydrothermally synthesized33,34 from GO1 and GO2, and named GA1 and GA2, respectively.

Table S1 illustrates the comparison of our GO and other GO synthesized by various methods with respect to the material ratio graphite:oxidant:solvent (Gr:Od:Sv, w/w/v), reaction time, C/O atomic ratio and the yield. It shows that in Hummers method, a typical material ratio of 1:3.5:23 and reaction time of about 2 hours are selected, which leads to low yield and toxic byproduct. To overcome these problems, high material ratio and long reaction time were employed in Kovtyukhova’s20 (Gr:Od:Sv = 1:6:50, 8 h) and Marcano’s22 (Gr:Od:Sv = 1:6:133, 12 h) work, and lower C/O ratio was achieved in the former work (1.98). In contrast, Chen’s19 and Gao’s25 routines reduced the reaction time, but the material ratio was still high. As compared to previous work, our strategy is much more economical with the least material consumption (Gr:Od:Sv = 1:1.5:10), short reaction time (5 h), and high yield (up to 84%). Our improvement works can be ascribed to following factors: (1) the intercalation and preoxidation of flake graphite is enhanced by using K2FeO4 as a stronger oxidant25,35 which partly replaces KMnO4 at extended low-temperature stage; (2) the secondary feeding of KMnO4 prevents it from fast decomposition and keeps the strong oxidability of concentrated sulfuric acid; (3) the reduced amount of sulfuric acid increases the concentration of graphite and oxidants, which improves the kinetics of the reaction and the utilization of the reactants.

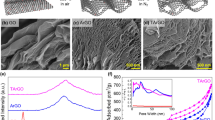

Figure 2 demonstrates (a,b) the photographs, (c) AFM image and (d,e) FESEM images of several samples. As shown in the inset of Fig. 2a, both GO1 and GO2 aqueous solutions appear typical brownish, and there is little difference in color between them, which implies the GOs obtained from the two different methods are quite similar. A small amount of GO2 solution air-dried over a watch-glass gives a sheet of flexible GO2 paper (Fig. 2a), which is easily bent or tore. In contrast, GA2 exhibits a dark foam-like monolith (Fig. 2b), and it is so lightweight that can be supported over leaves of the pot plant. AFM images (Fig. 2c and Fig. S1) show the initial GO2 nanosheets are very irregular in morphology and have a lateral size of a few microns and a thickness of 1.5~2 nm, which corresponds to 2~3 layers of atoms. FESEM image (Fig. 2d) reveals GA2 is porous with abundant macropores of about 10~20 μm in size, meantime, a tremendous amount of reduced GO2 nanosheets self-assemble into three-dimensional conducting networks, as observed elsewhere33,34. These reduced GO2 nanosheets are so thin as to look transparent (Fig. 2e).

XRD patterns of the pristine graphite, GO1 and GO2 are given in Fig. S2. The strong peak at 2θ = 26.5° presents the (002) plane7,9 of pristine graphite with high crystallinity, while the weak peak located at 10~11° is an indicative of (001) plane of dispersed GO. The calculated interlayer spacing is 0.833 nm and 0.816 nm (see the inset) for GO1 and GO2, respectively, suggesting that both GO1 and GO2 were exfoliated thoroughly after the oxidation, and shared a similar interlayer spacing.

Figure 3 shows the TGA (a) and UV-vis spectra (b) of GO1 and GO2. In TGA (Fig. 3a), prominent weight loss occurs at about 200 °C, which is attributed to the pyrolysis of most oxygen-containing groups18,19, while the weight loss above 250 °C can be explained by the slow removal of the residual groups. The only difference is that weight loss of GO1 is slightly more than that of GO2, which implies more oxygen-containing groups formed in GO1. In UV-Vis spectra (Fig. 3b), the main peak at 230 nm and the shoulder peak at 300 nm stand for π-π* transitions of C=C bond from graphitic carbon of GO and n-π* transitions of C=O bond from oxidized carbon of GO22,25, respectively. Hence, GO1and GO2 exhibit similar characteristics in both TGA and UV-vis spectra, and indicate that they are similar in domain structures with similar oxygen groups.

Figure 4 shows the typical FTIR (a) and RS (b) of GO1 and GO2. From the FTIR spectra, the same functional groups are identified for GO1 and GO2 as O–H stretching (3420 cm−1) and bending (1380 cm−1), C=O stretching (1730 cm−1), C=C stretching (1630 cm−1), C–O stretching (1260 cm−1) and C–O–C stretching (1080 cm−1) vibrations. The corresponding RS (Fig. 4b) were characterized by two typical peaks, G-band (1574 cm−1) and D-band (1360 cm−1). The G-band reflects the first order scattering of E2g phonon of graphitic carbon, while D-band (1360 cm−1) relates to the formation of defects and disorder25,36, such as grain boundaries, hetero-atoms introduced in graphene planes, etc. In fact, GO sheet consists of two kinds of domains37: graphitic domains inherited from their parent graphite and highly oxidized domains due to oxidation. Therefore, D-band mainly records the information of GO distinct from graphite, especially the oxidation-induced defects and disorder, and the intensity ratio of D-band to G-band, ID/IG, indirectly reflects the oxidation degree24,38,39. Here the value of ID/IG is 1.07 for GO1 and 0.94 for GO2, which indicates that abundant defects were introduced in GO during oxidation, and GO1 has a higher oxidation degree than GO2. A similar phenomenon was reported by Kim group36.

The chemical states of GO1 and GO2 were investigated by XPS (Fig. 5). Figure 5a shows GO1 and GO2 have very similar survey spectra where C and O coexist as main elements. GO1 and GO2 were further compared with respect to C1s spectra normalized to C=C peak (284.6 eV) in Fig. 5b. It is clear that GO1 has a higher intensity of right peak correlated with oxidized carbon in C1s. In addition, quantitative analysis reveals that the C to O ratio is 1.98 for GO1 and 2.12 for GO2, respectively. The two points above arrive at a consistent conclusion that GO was successfully synthesized10, and GO2 has a lower oxidation degree than GO122, supporting the results of TGA and RS. To resolve the bond components, C1s and O1s spectra of GO2 were deconvoluted in Fig. 5c,d, respectively. Figure 5c shows four types of covalently bonded carbon existing in GO2 as sp2 carbon (C-C/C=C, 284.6 eV), epoxy/hydroxyl groups (C–O, 286.6 eV), carbonyl groups (C=O, 287.8 eV) and carboxyl groups (O–C=O, 289.5 eV), respectively. Meanwhile, the oxygen in GO2 (Fig. 5d) can be resolved in the form of C=O bond (531.3 eV), C-O bond (532.4 eV) and possibly adsorbed H2O (533.2 eV). These results agree with the reported data of GO19,22,25.

As an example of GO application, GA was tested as the free-standing supercapacitor electrode. As shown in Fig. 6, the electrochemical properties of GA were characterized by CV, GCD, EIS and cycle stability curves, respectively. The nearly rectangular CV curves (Fig. 6a) obtained at a scan rate of 5 mV/s reveal mostly the electrical-double-layer (EDL) capacitance characteristic of GA33,34, and GA2 has a bigger area of CV loop and specific capacitance as compared to GA1. The nearly linear and symmetric GCD curves (Fig. 6b) are another characterization of EDL capacitance. In the curves, the initial vertical section of discharge curve presents the voltage drop correlated with inner resistance (IR) of electrodes, so GA2 has smaller IR than GA1. This can be further confirmed by the EIS (Fig. 6c), in which the intersection (standing for the IR) of GA2 curve is clearly ahead of that of GA1. Finally, we evaluated the circle stability of GA in Fig. 6d by plotting specific capacitance (calculated from GCD curves7,34) vs charge/discharge number, where large current density of 10A/g was applied. It shows that upon circling for 10000 times, the capacitance of both GA1 and GA2 keeps almost constant. This excellent stability can be ascribed to the robust three-dimensional conducting networks within GA, which provide direct and stable pathway of electron transport required for EDL capacitance. In addition, higher capacitance and lower IR obtained in GA2 than those of GA1 can be explained by the fact that GO2 suffered from weaker oxidation and lower structural defect than GO1. Full comparison of electrochemical properties between GA1 and GA2 was summarized in Table S2. The good electrochemical properties indicate that GA2 is a promising candidate for EDL supercapacitor electrodes.

Discussion

In summary, to synthesize GO economically and efficiently, we made an attempt to improve the existing NaNO3-free Hummers methods based on a one-pot routine by three main points: first, partly replacing KMnO4 with K2FeO4 of higher oxidability at low temperature to enhance the intercalation and preoxidation of graphite; second, two-step feeding of KMnO4 elevates the utilization of oxidants; third, reduced amount of concentrated H2SO4 increases the concentration of graphite and oxidants, and improves the kinetics of oxidation process. As compared to those protocols reported, our routine has high competitiveness in material consumption, both for the oxidants and the intercalating agents, meanwhile, the reaction can be completed within a shorter time. We demonstrated that with the ingredient ratio of graphite: oxidant: intercalating agent = 1:1.5:10 (w/w/v), graphite can be efficiently converted to GO within 5 hours. The improved Hummers method can be used to synthesize GO and its derivatives in an economical, eco-friendly, and large-scale way.

Methods

Materials

Natural flake graphite (325 meshes) was purchased from Qingdao Meilikun Co. Ltd., China, K2FeO4(AR) was provided by Hubei CSW Chemistry Co., Ltd., China. All other regents were received from Aladdin Industrial Corporation and used without any further purification.

Synthesis of GO

Typically, flake graphite (10 g), KMnO4 (6 g) and K2FeO4 (4 g) as the oxidants, and boric acid (0.01 g) as a stabilizer were first dispersed in 100 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid in a vessel and stirred for 1.5 h at less than 5 °C. After the addition of another KMnO4 (5 g), the vessel was transferred into a water bath at about 35 °C and stirred for another 3 h to complete the deep oxidation. Next, as 250 mL of deionized water was slowly added, the temperature was adjusted to 95 °C and held for 15 minutes, when the diluted suspension turned brown, indicating the hydrolysis and absolute exfoliation of intercalated graphite oxide. Finally, this brown suspension was further treated with 12 mL H2O2 (30%) to reduce the residual oxidants and intermediates to soluble sulfate, then centrifuged at 10000 rpm for 20 min to remove the residual graphite, and washed with 1 mol/L HCl and deionized water repeatedly, producing the terminal GO (designated GO2). For comparison, another GO (designated GO1) was synthesized following Kovtyukhova improved Hummers method20, except two of little modification: (1) the ingredients were adjusted slightly, as shown in Table S1; (2) both preoxidation and oxidation time was set at 4 hours.

Synthesis of GA

GA was prepared from GO according to hydrothermal method33,34. Typically, 25 mL of 2 mg/ml GO1 (or GO2) aqueous solution obtained above was sealed in a Teflon lined stainless-steel autoclave, and hydrothermally reduced at 180 °C for 12 h. After the autoclave was cooled and discharged, the reduced GO1 (or GO2) was obtained and subsequently freeze-dried for 24 h at −55 °C, which gives a porous graphene monolith, coined as GA1 (or GA2).

Preparation of GA electrode

GA slice (diameter ~1 cm, thickness~1 mm) was cut from GA bulk, then mechanically pressed over a Ni foam under a pressure of 10 MPa, acting as GA electrode.

Characterization of materials

Optical absorption spectra of GO solution were taken from an ultraviolet visible spectrophotometer (UV-vis, Shimadzu UV-3600). Chemical structure of GO was analyzed using Fourier transformation infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, Bruker IFS66V), Raman spectroscopy (RS, Renishaw) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Kratos Axis Supra) with Al-Ka radiation). The weight loss of samples was measured by thermal gravimetric analyzer (TGA, STA 449 C TG-DSC) with a heating rate of 10 °C/min under Ar gas flow of 50 mL/min. The phases were identified by X-ray diffractometer (XRD, PANalytical X’Pert PRO) with Cu-Ka radiation. The morphology of samples was characterized using field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM, JEOL JSM-6701F) and atomic force microscopy (AFM, Bruker, Dimension edge).

Electrochemical tests

Cyclic voltammetry(CV), galvanostatic charge/discharge(GCD) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) were measured based on a three-electrode cell system: the GA electrode as working electrode, a Pt plate as counter electrode and a calomel electrode as reference electrode, respectively, which uses 1 mol/L of H2SO4 as electrolyte. The CV and EIS were acquired using an electrochemical workstation (CHI 660E, Shanghai CHI, China), while GCD performance was taken by a Battery Test System (Land 2001, Wuhan Kingnuo, China).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Yu, H. et al. High-efficient Synthesis of Graphene Oxide Based on Improved Hummers Method. Sci. Rep. 6, 36143; doi: 10.1038/srep36143 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 306, 666–669 (2004).

Choi, W. & Lee, J. Graphene: Synthesis and Applications. (Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, 2012).

Eigler, S. & Hirsch, A. Chemistry with Graphene and Graphene Oxide – Challenges for Synthetic Chemists. Angew Chem Int Ed. 53, 2–21 (2014).

Spitalsky, Z., Danko, M. & Mosnacek, J. Preparation of functionalized graphene sheets. Curr Org Chem. 15, 1133–1150 (2011).

Dreyer, D. R., Park, S., Bielawski, C. W. & Ruoff, R. S. The chemistry of graphene oxide. Chem Soc Rev. 39, 228–240 (2010).

Obatal, S. et al. Graphene Oxide: A Fertile Nanosheet for Various Applications. J Phys Soc Japan. 84, 121012 (2015).

Wang, L., Xing, R., Zhang, B. & Hou, Y. Preparation and Electrochemical Properties of Functionalized Graphene/Polyaniline Composite Electrode Materials. Acta Phys Chim Sin. 30, 1659–1666 (2014).

Xing, R., Li, Y. & Yu, H. Preparation of fluoro-functionalized graphene oxide via the Hunsdiecker reaction. Chem Commun. 52, 390–393 (2016).

Dimiev, A. M. & Tour, J. M. Mechanism of Graphene Oxide Formation. ACS Nano. 8, 3060–3068 (2014).

Shamaila, S., Sajjad, A. K. L. & Anum I. Modifications in development of graphene oxide synthetic routes. Chem Eng J. 294, 458–477 (2016).

Ambrosi, A. & Pumera, M. Electrochemically Exfoliated Graphene and Graphene Oxide for Energy Storage and Electrochemistry Applications. Chem Eur J. 22, 153–159 (2016).

Wazir, A. H. & Kundi, I. W. Synthesis of Graphene Nano Sheets by the Rapid Reduction of Electrochemically Exfoliated Graphene Oxide Induced by Microwaves. J Chem Soc Pak. 38, 11–16 (2016).

Brodie, B. C. On the Atomic Weight of Graphite. Philos Trans R Soc London 14, 249–259 (1859).

Staudenmaier, L. Verfahren zur Darstellung der Graphitsäure. Ber Dtsch Chem Ges. 31, 1481–1487 (1898).

Hummers, W. S. & Offeman, R. E. Preparation of Graphitic Oxide. J Am Chem Soc. 80, 1339 (1958).

Pan, S. & Aksay, I. A. Factors Controlling the Size of Graphene Oxide Sheets Produced via the Graphite Oxide Route. ACS Nano 5, 4073–4083 (2011).

Allaedini,G., Mahmoudi, E., Aminayi,P., Tasirin, S. M. & Mohammad, A. W. Optical investigation of reduced graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide/CNTs grown via simple CVD method, Synthetic Metals. 220, 72–77 (2016).

Chen, J., Yao, B., Li, C. & Shi, G. An improved Hummers method for eco-friendly synthesis of graphene oxide. Carbon. 64, 225–229 (2013).

Chen, J., Li, Y., Huang, L., Li, C. & Shi, G. High-yield preparation of graphene oxide from small graphite flakes via an improved Hummers method with a simple purification process. Carbon. 81, 826–834 (2015).

Kovtyukhova, N. et al. Layer-by-layer assembly of ultrathin composite films from micron-sized graphite oxide sheets and polycations. Chem.Mater. 11, 771–778 (1999).

Sun, J. et al. Fully Converting Graphite into Graphene Oxide Hydrogels by Preoxidation with Impure Manganese Dioxide. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 7, 21356–21363 (2015).

Marcano, D. C. et al. Improved synthesis of graphene oxide. ACS Nano. 4, 4806–4814 (2010).

Liou, Y., Tsai, B. & Huang, W. An economic route to mass production of graphene oxide solution for preparing graphene oxide papers. Mater Sci and Eng B. 193, 37–40 (2015).

Hua, Y., Song, S. & Lopez-Valdivieso, A. Effects of oxidation on the defect of reduced graphene oxides in graphene preparation. J Colloid and Interf Sci. 450, 68–73 (2015).

Peng, L. et al. An iron-based green approach to 1-h production of single-layer graphene oxide. Nature Comm. 6, 5716 (2015).

Gao, C. et al. A green method to fast prepare single-layer graphene oxide. China patent, CN104310385A. 2015 JAN 28. (in Chinese).

Yu, C., Wang, C. & Chen, S. Facile Access to Graphene Oxide from Ferro-Induced Oxidation. Sci Rep. 6, 17071 (2016).

Sun, L. & Fugetsu, B. Mass production of graphene oxide from expanded graphite. Mater Lett. 109, 207–210 (2013).

Shao, G. et al. Graphene oxide: the mechanisms of oxidation and exfoliation. J Mater Sci. 47, 4400–4409 (2012).

Ye, Z. et al. A Novel Micro-Nano Structure Profile Control Agent: Graphene Oxide Dispersion. Nanomater 2014, 582089 (2014).

Thomas, D. & Assoc, P. Feasibility of Wastewater Treatment with Ferrate. Environ Eng Div. 105, 1023–1034 (1979).

Sorokina, N. E., Khaskov, M. A., Avdeev, V. V. & Nikol’skaya, I. V. Reaction of Graphite with Sulfuric Acid in the Presence of KMnO4 . Russ J Gen Chem. 75, 162–168 (2005).

Wu, Z. et al. Three-Dimensional Nitrogen and Boron Co-doped Graphene for High-Performance All-Solid-State Supercapacitors. Adv Mater. 24, 5130–5135 (2012).

Xu, Y. et al. Flexible Solid-State Supercapacitors Based on Three-Dimensional Graphene Hydrogel Films. ACS Nano. 7, 4042–4049 (2013).

Delaude, L. & Laszlo, P. A novel oxidizing reagent based on potassium ferrate (VI). Organ Chem. 61, 6360–6370 (1996).

Krishnamoorthy, K., Veerapandian, M., Yun, K. & Kim, S. J. The chemical and strutural analysis of graphene oxide with different degrees of oxidation. Carbon. 53, 38–49 (2013).

Ayán-Varela, M. et al. A quantitative analysis of the dispersion behavior of reduced graphene oxide in solvents. Carbon. 75, 390–400 (2014).

Liu, Z. et al. Controlling and formation mechanism of oxygen-containing groups on graphite oxide. Indus & Eng Chem Res. 53, 253–258 (2014).

Huang, Q., Sun, H. & Yang, Y. Spectroscopy characterization and analysis of graphite oxide. Chin J inorganic chem. 27, 1721–1726 (in Chinese) (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by natural science foundation of China (51164026).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.Y. and B.Z. conceived the project and designed the experiments. H.Y. and C.B. performed the experiments and characterizations. R.L. and R.X. took part in the analysis of results, B.Z. and H.Y. wrote the paper, and all of the authors read and revised the paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, H., Zhang, B., Bulin, C. et al. High-efficient Synthesis of Graphene Oxide Based on Improved Hummers Method. Sci Rep 6, 36143 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36143

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36143

This article is cited by

-

Designed and tailor-made double hydrophilic block copolymer-graphene nanoplatelet hybrids for reinforcing epoxy thermosets

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Adsorption of contaminants by nanomaterials synthesized by green and conventional routes: a critical review

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2024)

-

Reduced graphene oxide (rGO) and 5, 10, 15, 20-tetra-p-tolyl-21H, 23H-porphine (TPTP) composite: highly reproducible and repeatable chemiresistive SO2 sensor

Applied Physics A (2024)

-

Resistive Switching Properties in Copper Oxide–Graphene Oxide Nanocomposite-Based Devices for Flexible Electronic Applications

Journal of Electronic Materials (2024)

-

Adsorptive removal of sulphonamides in water by graphene oxide-doped porous polycarbonate derived from optical disc waste

International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology (2024)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.