Abstract

This study aimed to compare the efficacy and safety of EUS-guided ethanol injection and 125I seed brachytherapy for malignant left-sided liver tumors which were difficult for trans-abdominal intervention. The study protocol was registered at Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02816944). Twenty-six patients were consecutively and prospectively hospitalized for EUS-guided interventional treatment of refractory malignant left-sided liver tumors between June 2014 and June 2016. Liver masses were detected using EUS in 25 of 26 (96.2%) patients. EUS-guided interventional treatment was completed uneventfully in 23 of 26 (88.5%) patients using anhydrous ethanol injection (n = 10) or iodine-125 seed implantation (n = 13). Six months later, complete response was achieved in 15 of 23 (65.2%) patients and partial response in 8 of 23 (34.8%) patients. Patients with tumor residual have second-look EUS-guided interventional treatment (n = 5), radiotherapy (n = 2) or surgical resection (n = 1). Complete response was achieved after repeated interventional treatment in 3 of 5 patients who underwent second EUS-guided intervention; 2 patients required additional surgical resection but one succeed. No significant complications occurred. Therefore EUS-guided 125I seed brachytherapy is an effective and safe treatment modality for radical operation or promising palliative control of malignant left-sided liver tumors refractory to trans-abdominal intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Malignant liver tumors, also known as liver cancer, chiefly consist of primary and metastatic hepatic and intrahepatic bile duct cancers, such as hepatocellular carcinoma, colorectal cancer liver metastasis, and cholangiocarcinoma1. Liver cancer, which is usually asymptomatic at an early stage, may be incidentally detected on abdominal imaging scans, including those obtained by ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or may manifest with signs and symptoms including abdominal pain, jaundice, hepatomegaly, abdominal mass, or hepatic dysfunction at a relatively late stage, at which point they are generally associated with a poor prognosis. Radical hepatectomy alone or followed by orthotopic liver transplantation remains the mainstay of treatment for resectable primary liver cancers2, while radical resection of liver metastases is also beneficial for eligible colorectal cancer patients after neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy3.

A majority of liver cancer cases are surgically refractory or unresectable possible because of underlying medical conditions, multiple or oversized liver diseases, or involvement of major vessels4. Palliative therapy, an alternative to definitive treatment, may help to improve patient survival and quality of life in these settings. Multiple palliative treatment regimens, including transarterial chemoembolization5, ablation using anhydrous ethanol injection6, high-intensity focused ultrasound7 or radiofrequency8, iodine-125 brachytherapy9, and photodynamic therapy10, have been used to control primary and secondary liver cancers. Among these documented palliative treatment modalities, ethanol injection and iodine-125 brachytherapy have shown promising therapeutic effects in liver cancer patients. These two treatment regimens are normally performed percutaneous access. In a few cases, thermal ablation performed in open surgery or under laparoscopy. While percutaneous intervention is generally thought to be minimally invasive, it may not be feasible for some patients with left hepatic lobe atrophy, lesion was located at the surgical margin of the left liver or in the caudate lobe, gastrointestinal flatulence and abdominal skin surgical scar. At this time, the conventional trans-abdominal ultrasound has difficulty to display lesions or even unable to discover it.

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) is an advanced endoscopic technique primarily used for the characterization and biopsy of the gastrointestinal tract, particularly for preoperative staging of malignant diseases, including oesophageal, gastric, and pancreatic cancers11. As left lobe of the liver is located in front of the lower esophagus, stomachus cardiacus and in proximity to the gastric lesser curvature, it is accessible on EUS, have better image quality and more adjacent to the focus. Therefore it is possible to interventionally treat left-sided liver tumors through EUS, especially when other percutaneous intervention is not deemed feasible or safe. The present work aimed to compare the efficacy and safety of EUS-guided ethanol injection and 125I seed brachytherapy for malignant liver tumors located in the left lobe that are refractory to conventional percutaneous intervention.

Results

Demographic and clinical data

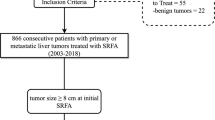

Overall, 26 patients were enrolled in this study, including 17 men and 9 women, aged 31–75 years. The basic characteristic of included patients was summarized in Table 1. The aetiologies of the hepatic tumors were chronic hepatitis (n = 6), liver cirrhosis (n = 11), and primary gastrointestinal malignancy (n = 9). Twenty-one patients had a single left-sided liver tumor, and 5 patients had more than one liver tumor with major disease located in the left lobe but multiple tumors in the right lobe. Liver tumors were occurred in left liver shadowed by gastrointestinal (GI) gas (n = 12; Fig. 1), resection margin (n = 7; Fig. 2), caudate lobe (n = 3; Fig. 3), significantly atrophic left lobe (n = 2), and remarkable abdominal skin scar (n = 2). All tumors were not detectable or poorly visualised on percutaneous ultrasound scan because of the above reason. In addition, a systematic review by searching from PubMed up to August 2016 was performed. The summary of 11 studies of ethanol ablation and 125I brachytherapy of the hepatocellular carcinoma was presented in Table 2 12,13,14,15,16,17 and Table 3 9,18,19,20,21.

EUS-guided iodine-125 brachytherapy for postoperative liver metastasis of cholangiocarcinoma.

(A) presence of a 1.3-cm, low-density liver mass located in the left lobe on CT scan (white arrows). US image failed to show the lesions due to the gas ahead; (B) identification of a 1.5 cm × 1.3 cm low-echodensity mass on EUS (white arrows); (C) EUS-guided implantation of iodine-125 particles (white arrows); (D) obvious downsizing of the liver disease on follow-up CT scan at 1 months (white arrows); and (E) disappearance of the liver disease on follow-up MRI scan taken after 12 months.

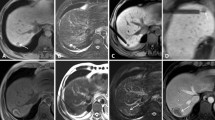

EUS-guided anhydrous ethanol ablation for postoperative liver recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma.

(A) presence of a 1.5 cm × 1.1 cm postoperative liver recurrence located on the resection margin as shown on T2-weighted MRI scans (white arrows), but conventional US image failed to show the lesions; (B) EUS-guided ethanol injection; and (C) arterial phase (arrowhead) and (D) parenchymal phase (arrowhead): non-enhanced liver disease on follow-up contrast CT scan revealed complete resolution of disease at 12 months.

EUS-guided anhydrous ethanol ablation for lesions in liver caudate lobe.

MRI imaging in liver caudate lobe showed a lesion of low T1 signal intensity (A) (arrowhead) and significant enhancement in arterial phase (B) (arrowhead). (C) at liver caudate lobe EUS scan showed a well-defined hypoechoic 1.9*1.6 cm lesion (arrows). (D) It indicated that 22G biopsy needle with EUS guidance was inserted into the lesion along with the needle sheath (arrowhead), and (E) diffuse increase in echogenicity covering the whole mass after the percutaneously punctured injection of anhydrous alcohol. After 1 month follow-up, MR scan was seen high T1-weighted signal intensity (F) (arrowhead) and no obvious enhancement during arterial (G) (arrowhead) and substance phase (H) (arrowhead). After 15 months follow-up, it showed high T1-weighted signal intensity (I) (arrowhead) and contrast material-enhanced MR images showed completed ablation without enhanced lesions (J) (arrowhead).

EUS data

Out of the 26 patients, left-sided liver tumors were detectable in all cases on EUS with the exception of one (1/26, 3.8%) case in which the tumor was located in an atrophic left lobe. Of these 25 cases, 23 were successfully and uneventfully treated using interventional EUS (anhydrous ethanol, n = 10; iodine-125 implant, n = 13) as scheduled. Interventional treatment failed in two patients due to an overly large puncture angulation. Operative time was 10–70 minutes, and no blood loss. No clinically significant procedure-related morbidities occurred.

Tumor response and mid-term follow-up data

All patients were followed up for 1–2.5 years as scheduled. At 12 months after treatment, 12 of 13 (92.3%) patients achieved complete tumor response in iodine-125 particle implantation (Fig. 1) while 3 of 10 (30%) in anhydrous ethanol ablation (Fig. 3 and Table 4). Residual tumor was detected in 8 patients after anhydrous ethanol ablation (n = 2) or iodine-125 particle implantation (n = 6); these patients were further treated with second-look EUS-guided interventional treatment (n = 5) and radiotherapy (n = 2) and surgical resection (n = 1). Complete response was achieved after again EUS-guided treatment in 3 of 5 patients, whereas the remaining 2 patients required surgical resection but only one succeed. Recurrence was observed in 2 patients at 1 year after anhydrous ethanol ablation. No clinically significant late-onset complications occurred.

Discussion

Interventional EUS, namely, EUS-guided interventional treatment, has been reported for drainage of pancreatic22 or bile duct (pseudo) cysts23 or even complex choledochoduodenostomy24. This newly emerging interventional treatment incorporating ethanol or chemotherapy injection, brachytherapy, and/or photodynamic therapy has also been piloted in preclinical studies and a small series of clinical studies for the treatment of malignant pancreatic, lower common bile duct, and periampullary diseases25. In contrast, EUS is used relatively less frequently for the treatment of hepatic tumors. Awad et al.26 reported that EUS could detect small-sized primary and secondary liver cancers previously undetectable on CT scans, and simultaneous fine-needle biopsy aided in the diagnosis of deep-seated liver tumors for preoperative staging. Singh et al.27 also reported, in a small series of prospective patients, that EUS exhibited a higher specificity and positive predictive value than CT and percutaneous ultrasound scanning for metastatic liver tumors located in hepatic segments II and III. Furthermore, interventional EUS has been attempted for transgastric drainage of liver abscess28 and infectious biloma after radiofrequency-ablated hepatocellular carcinoma29. To the best of our knowledge, the present work is the first prospective study comparing the therapeutic role of EUS-guided ethanol injection and 125I seed brachytherapy in the treatment of left-sided liver malignancies.

Percutaneous ultrasonography-guided interventional treatment normally requires an acoustic window to clearly display the liver tumor and allow subsequent ethanol injection, high-intensity focused ultrasound30, or other ablation therapy. However, in some patients, such as those enrolled in the current study, hepatic tumors cannot be detected or clearly visualised on percutaneous ultrasound scanning because of distorted liver anatomy from a previous operation, a deep-seated location such as the caudate lobe, at the edge of liver, at the surgical margin that usually affected by gastrointestinal gas or a pre-existing abdominal scar. For left-sided liver tumors, especially when located in proximity to the lesser curvature of the stomach, transgastric EUS can exclude the interference of intestinal gas and provide safe liver access for ethanol injection and iodine-125 implantation. Our results showed that EUS-guided iodine-125 brachytherapy has a better prognosis and less recurrence for left-sided liver tumors with a good safety profile comparing to ethanol ablation. Moreover, iodine-125 implantation is recommended for the treatment of larger tumors because of a higher risk of residual or recurrent tumor. In previous study, it was reported that the 1-, 3- and 5-year recurrence-free rates of the 125I brachytherapy after resection of HCC were 94.12%, 76.42%, and 73.65%, and their overall survival rates were 94.12%, 73.53%, and 55.88%, respectively9, which was also similar to another study21. This may result from that a high-dose short radiation emitted by 125I could be continuous within the the target tissues for a long half-life of 59.4 days, which would trigger tumor cell apoptosis and drop proliferation of tumor cells by gathering cells in the radiosensitive cell cycle phase (G2/M)20,31. The radiation declined sharply with the distance from the seeds and had limited injury to surrounding normal tissues. Meanwhile, 125I implantation also could excite the anti-tumor immune response in HCC patients by adding CD3+ and CD4+ immunocytes and facilitating Th2/Th1 deviation32. Thus these findings indicated that EUS-guided 125I brachytherapy could be a safe and feasible way to effectively target tumor cells and minimize injury to healthy tissues.

There are some limitations regarding EUS-guided interventional treatment of liver cancer. First, interventional EUS requires a more delicate ultrasound system and greater operator expertise; therefore, this interventional technique is less feasible in general ultrasonographic practice. Second, transgastric EUS can only access a relatively small portion of the left lobe; an overly large puncture angulation failed the pre-planned interventional therapy in 2 of our patients. Third, implantation of radioactive particles is relatively complex through a EUS puncture needle compared to the percutaneous approach.

In conclusion, EUS-guided iodine-125 brachytherapy is an effective alternative to ethanol injection for radical operation or promising palliative control of refractory malignant left-sided liver tumors. This technique is minimally invasive and associated with a good safety profile, and residual tumor can be treated by repeated sessions of interventional EUS. The long-term efficacy and safety of interventional EUS have yet to be investigated in large-scale, comparative studies, especially studies evaluating patients’ survival and quality of life.

Patients and Methods

Patient selection

Between June 2014 and June 2016, 26 patients with primary or metastatic left-sided liver tumors diagnosed on abdominal ultrasound, CT, and/or MRI scans, who were ineligible for surgical treatment due to unresectable disease or high risk of surgical morbidity, were consecutively and prospectively referred to our ultrasound centre for palliative treatment. The included patients were randomly divided into two groups: 10 in the anhydrous ethanol group and 13 in the iodine-125 implantation group. Inclusion criteria were as follows: American Society of Anaesthesiologists physical status class I and II; relatively well confined, single hepatic tumor or extensive hepatic tumor (in the scenario of multiple foci) located in Couinaud segments I–III refractory to percutaneous access; liver tumor that could not be visualised or not clearly visualised on percutaneous ultrasound; and generally normal or compensated liver function (Child-Pugh classes A and B). Exclusion criteria were as follows: a known history of or suspected upper gastrointestinal stenosis or stricture; complicating oesophagogastric varices or bleeding; pre-existing serious cardiopulmonary or hepatorenal functional impairment or coagulopathy; extensive intra- or extrahepatic metastases; or refusal to participate in the study. All patients provided informed consent in writing prior to enrolment.

Ethical issues

This was designed as a randomized, open-label, control study. The clinical trial was registered in Clinicaltrials.gov ID: NCT02816944 on June 23th 2016. All patients and relatives were informed about the purpose and procedures of this study and gave written informed consent. Eligible patients were randomly allocated into the 125I brachytherapy group and the control group of ethanol ablation. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou and all studies were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

EUS and interventional treatment procedures

All patients underwent routine hematologic, clinical biochemical, coagulative function, virologic, and oncologic assays prior to interventional EUS. All interventional procedures were performed by an assigned interventional treatment team led by a board-certified interventional physician, including resident interventional physicians, radiologists, and research nurses.

Left-sided liver EUS was performed as previously described28. Briefly, the patient was placed in the left recumbent position and sedated using intravenous propofol. After excluding the presence of oesophagogastricvarices using conventional endoscopy, a Pentax endoscopic ultrasound system (Pentax Medical, Tokyo, Japan) incorporating a Hitachi colour Doppler ultrasound scanner (Hitachi Medical, Tokyo, Japan) was used for EUS of the left-sided liver. An endoscopic ultrasound injection needle (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA) was used for injection of anhydrous ethanol (22G) for well-encapsulated primary hepatocellular carcinoma or implantation of iodine-125 particles (19G; Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA) for hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocellular carcinoma or metastatic liver cancer.

Postoperative care, follow-up procedure, and main outcome measures

Patients were closely followed after EUS and treated with antimicrobial, haemostatic, and hepatoprotective agents as indicated. All patients were followed up at the outpatient clinic using abdominal ultrasound, CT, and/or MRI at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively. The main outcome measures were frequency of detection by EUS, tumor response as defined by the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors30 at 6 months, and interventional EUS-associated morbidities. In this study, all statistical analysis was performed using x2, Fisher exact test and Student t test by spss 13.0 software.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Jiang, T.-a et al. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic ultrasonography-guided interventional treatment for refractory malignant left-sided liver tumors: a case series of 26 patients. Sci. Rep. 6, 36098; doi: 10.1038/srep36098 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Fowler, K. J., Saad, N. E. & Linehan, D. Imaging approach to hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, and metastatic colorectal cancer. Surgical oncology clinics of North America 24, 19–40, doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2014.09.002 (2015).

Pichlmayr, R., Weimann, A., Tusch, G. & Schlitt, H. J. Indications and Role of Liver Transplantation for Malignant Tumors. The oncologist 2, 164–170 (1997).

Khan, K., Wale, A., Brown, G. & Chau, I. Colorectal cancer with liver metastases: neoadjuvant chemotherapy, surgical resection first or palliation alone? World journal of gastroenterology 20, 12391–12406, doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i35.12391 (2014).

Wang, H. M. et al. Analysis of facial bone wall dimensions and sagittal root position in the maxillary esthetic zone: a retrospective study using cone beam computed tomography. The International journal of oral & maxillofacial implants 29, 1123–1129, doi: 10.11607/jomi.3348 (2014).

Takayasu, K. et al. Prospective cohort study of transarterial chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in 8510 patients. Gastroenterology 131, 461–469, doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.05.021 (2006).

Horiguchi, Y. et al. Treatment of choice for unresectable small liver cancer: percutaneous ethanol injection therapy or transarterial chemoembolization therapy. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology 33 Suppl, S111–S114 (1994).

Hoang, N. H., Murad, H. Y., Ratnayaka, S. H., Chen, C. & Khismatullin, D. B. Synergistic ablation of liver tissue and liver cancer cells with high-intensity focused ultrasound and ethanol. Ultrasound in medicine & biology 40, 1869–1881, doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2014.02.026 (2014).

Weis, S., Franke, A., Mossner, J., Jakobsen, J. C. & Schoppmeyer, K. Radiofrequency (thermal) ablation versus no intervention or other interventions for hepatocellular carcinoma. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, CD003046, doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003046.pub3 (2013).

Chen, K. et al. Adjuvant iodine-125 brachytherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma after complete hepatectomy: a randomized controlled trial. PloS one 8, e57397, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057397 (2013).

Wang, J. D. et al. Optimal treatment opportunity for mTHPC-mediated photodynamic therapy of liver cancer. Lasers in medical science 28, 1541–1548, doi: 10.1007/s10103-012-1248-3 (2013).

Holt, B. & Varadarajulu, S. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration or fine needle biopsy: the beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Endoscopy 46, 1046–1048 (2014).

Nakaji, S., Hirata, N., Kobayashi, M., Shiratori, T. & Sanagawa, M. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided ethanol injection as a treatment for ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma in the left hepatic lobe. Endoscopy 47 Suppl 1, E558–E560, doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1393394 (2015).

Nakaji, S. et al. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided ethanol injection for hepatocellular carcinoma difficult to treat with percutaneous local treatment. Endoscopy 44 Suppl 2 UCTN, E380, doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1309918 (2012).

Azab, M. et al. Radiofrequency ablation combined with percutaneous ethanol injection in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Arab journal of gastroenterology: the official publication of the Pan-Arab Association of Gastroenterology 12, 113–118, doi: 10.1016/j.ajg.2011.07.005 (2011).

Giorgio, A. et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma compared to percutaneous ethanol injection in treatment of cirrhotic patients: an Italian randomized controlled trial. Anticancer research 31, 2291–2295 (2011).

Brunello, F. et al. Radiofrequency ablation versus ethanol injection for early hepatocellular carcinoma: A randomized controlled trial. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology 43, 727–735, doi: 10.1080/00365520701885481 (2008).

Shiina, S. et al. A randomized controlled trial of radiofrequency ablation with ethanol injection for small hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 129, 122–130 (2005).

Zhang, W. et al. Placement of (1)(2)(5)I seed strands and stents for a type IV Klatskin tumor. World journal of gastroenterology 21, 373–376, doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i1.373 (2015).

Luo, J., Yan, Z., Liu, Q., Qu, X. & Wang, J. Endovascular placement of iodine-125 seed strand and stent combined with chemoembolization for treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma with tumor thrombus in main portal vein. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology: JVIR 22, 479–489, doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.11.029 (2011).

Zhang, F. J. et al. CT guided 125iodine seed implantation for portal vein tumor thrombus in primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Chinese medical journal 121, 2410–2414 (2008).

Nag, S., DeHaan, M., Scruggs, G., Mayr, N. & Martin, E. W. Long-term follow-up of patients of intrahepatic malignancies treated with iodine-125 brachytherapy. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics 64, 736–744, doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.08.029 (2006).

Bang, J. Y. & Varadarajulu, S. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided management of pancreatic pseudocysts and walled-off necrosis. Clinical endoscopy 47, 429–431, doi: 10.5946/ce.2014.47.5.429 (2014).

Puspok, A. et al. Endoscopic ultrasound guided therapy of benign and malignant biliary obstruction: a case series. The American journal of gastroenterology 100, 1743–1747, doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41806.x (2005).

Artifon, E. L. et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledochoduodenostomy and duodenal stenting in patients with unresectable periampullary cancer: one-step procedure by using linear echoendoscope. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology 48, 374–379, doi: 10.3109/00365521.2012.763176 (2013).

Zhang, W. Y., Li, Z. S. & Jin, Z. D. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided ethanol ablation therapy for tumors. World journal of gastroenterology 19, 3397–3403, doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i22.3397 (2013).

Awad, S. S. et al. Preoperative evaluation of hepatic lesions for the staging of hepatocellular and metastatic liver carcinoma using endoscopic ultrasonography. American journal of surgery 184, 601-604; discussion 604–605 (2002).

Singh, P. et al. Endoscopic ultrasound versus CT scan for detection of the metastases to the liver: results of a prospective comparative study. Journal of clinical gastroenterology 43, 367–373, doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318167b8cc (2009).

Tonozuka, R. et al. EUS-guided drainage of hepatic abscess and infected biloma using short and long metal stents (with videos). Gastrointestinal endoscopy 81, 1463–1469, doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.01.023 (2015).

Eso, Y., Marusawa, H., Tsumura, T., Okabe, Y. & Osaki, Y. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided transgastric drainage of infectious biloma following radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Digestive endoscopy: official journal of the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society 24, 390, doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2012.01305.x (2012).

Silva, M. F. et al. m-RECIST at 1 month and Child A are survival predictors after percutaneous ethanol injection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Annals of hepatology 13, 796–802 (2014).

Zhuang, H. Q., Wang, J. J., Liao, A. Y., Wang, J. D. & Zhao, Y. The biological effect of 125I seed continuous low dose rate irradiation in CL187 cells. Journal of experimental & clinical cancer research: CR 28, 12, doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-28-12 (2009).

Xiang, G. A., Chen, K. Y., Wang, H. N. & Xiao, J. F. [Immunological influence of iodine-125 implantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma resection]. Nan fang yi ke da xue xue bao = Journal of Southern Medical University 30, 292–294 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81572307), the Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang Province (2014C13G2010059). The funders had a role in preparation of the manuscript and publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.-l.W. and T.-a.J. conceived the project, designed the research and wrote the article. T.-a.J., Z.D., G.T. and Q.-y.Z. were responsible for the EUS treatment and clinical data collection. W.-l.W., T.-a.J. and Z.D. were responsible for statistical analysis. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, Ta., Deng, Z., Tian, G. et al. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic ultrasonography-guided interventional treatment for refractory malignant left-sided liver tumors: a case series of 26 patients. Sci Rep 6, 36098 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36098

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36098

This article is cited by

-

Peritumoral abnormalities on dynamic-enhanced CT after brachytherapy for hepatic malignancies: local progression or benign changes?

European Radiology (2022)

-

Treatment response and preliminary efficacy of hepatic tumour laser ablation under the guidance of percutaneous and endoscopic ultrasonography

World Journal of Surgical Oncology (2019)

-

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS)-guided laser ablation (LA) of adrenal metastasis from pancreatic adenocarcinoma

Lasers in Medical Science (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.