Abstract

High-resolution atmospheric-pressure scanning microprobe matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry imaging (AP-SMALDI MSI) at 10 μm pixel size was performed to unravel the spatio-chemical distribution of major secondary metabolites in the root of Paeonia lactiflora. The spatial distributions of two major classes of bioactive components, gallotannins and monoterpene glucosides, were investigated and visualized at the cellular level in tissue sections of P. lactiflora roots. Accordingly, other primary and secondary metabolites were imaged, including amino acids, carbohydrates, lipids and monoterpenes, indicating the capability of untargeted localization of metabolites by using high-resolution MSI platform. The employed AP-SMALDI MSI system provides significant technological advancement in the visualization of individual molecular species at the cellular level. In contrast to previous histochemical studies of tannins using unspecific staining reagents, individual gallotannin species were accurately localized and unequivocally discriminated from other phenolic components in the root tissues. High-quality ion images were obtained, providing significant clues for understanding the biosynthetic pathway of gallotannins and monoterpene glucosides and possibly helping to decipher the role of tannins in xylem cells differentiation and in the defence mechanisms of plants, as well as to investigate the interrelationship between tannins and lignins.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plant tissues can be thought of as highly organized chemical factories where diverse secondary metabolites are produced, transported and accumulated in specific compartments. Generally the roles of secondary metabolites in plants are considered to provide protection – either against other organisms such as herbivores and pathogenic bacteria or against exposure to UV light – to function as a pollination attractant, and even to provide a means for chemical communication with the surrounding environment1. Moreover, thousands of natural products have been isolated from plants and many have been shown to possess significant physiological effects upon human health and disease and are commonly used as herbal extracts and herbal medicines. Due to the prominent effect that secondary metabolites have on plants and humans, several analytical techniques have been used to identify their chemical structures, quantify contents and even map their spatial distribution2. While it is well-known that visualization of tissue/cell-specific localization of secondary metabolites provides straightforward clues to decipher their functions, techniques for this aim meet several challenges and are still in the developmental phase3,4. This is especially the case when comparing methods of secondary metabolite visualization to well-established approaches for localization of mRNA and proteins such as green fluorescent protein and protein-specific antibodies that are commonly used for the high-throughput determination of subcellular localization of macromolecules5. Traditional histochemical staining or immunohistochemical (IMH) approaches have been used for localization of small molecules, although these techniques are more adeptly applied to the localization of macromolecules. Intrinsic limitations of existing methods are either the inability to distinguish individual metabolites or the inherent loss/delocalization of small molecules that arises during rinsing and fixation steps of a typical staining process6.

Mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) has emerged over the past two decades to become a fundamental tool for label-free, untargeted spatio-chemical characterization of biological systems7. Owing to its unparalleled capabilities, a correlation of histological features with individual metabolites can go beyond the level of classical histochemical staining. In the field of MSI, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) imaging, introduced in the mid 1990’s8, is the most extensively used MSI technique for molecular imaging of both mammalian9 and plant tissues10. Besides MALDI, secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS)11 and various emerging ambient ionization techniques12, such as desorption electrospray ionization (DESI)13 and laser ablation electrospray ionization (LAESI)14, are the other popular sampling probes that have been employed in MS-based imaging measurements. SIMS imaging offers the highest spatial resolution among MSI techniques, down to tens of nanometers. However, major limitations of SIMS, including strong fragmentation of molecular ions and a relatively low signal intensity in the high mass range (m/z > 1000), have precluded its widespread use. DESI imaging is characterized by minimal sample preparation, but the spatial resolution is restricted to about 100 μm in routine analysis due to the difficulty in focusing charged droplets during spray15,16.

Also MALDI imaging experiments were performed for the localization of secondary metabolites in plant tissues, and previous approaches for mapping the distribution of plant metabolites were confined to 50–200 μm spatial resolution17. For plant tissues with numerous well-defined compartments, improvement in spatial resolution down to the cellular level provides access to a much greater chemical detail and therefore holds great potential to reveal the functions of tissue/cell-specific metabolites. For instance, asymmetric metabolic features in the cross section of maize leaf were mapped at 5 μm spatial resolution with an oversampling method18; C29 alkane distribution on surface of single pollen grains of Arabidopsis was resolved at ~12 μm spatial resolution19; as well as various metabolite distributions on intact seedling of A. thaliana were visualized below 10 μm spatial resolution20. Likewise, tissue-specific localization of free flavonoids in rhizome of liquorice was visualized in the cork layer with 10 μm laser pixel resolution6 and at 5 μm pixel resolution metabolites in wheat seed were visualized21. Recently, cell-specific localization of terpenoid indole alkaloids in the stem tissues of Catharanthus roseus was demonstrated with MALDI imaging and single-cell MS22. High spatial resolution alone is not sufficient to generate high quality ion images. The quality of an image also depends on high spectral resolution and high mass accuracy, with which nearly isobaric ions can be resolved, facilitating compound identification through a rapid search in online databases such as METLIN23. Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance (FT-ICR) and orbital trapping mass spectrometers are ultra-high resolution mass analysers, offering a mass resolving power greater than 100,000 and mass accuracies of better than 1 ppm. In this respect, our group recently introduced a high-performance atmospheric-pressure scanning microprobe MALDI (AP-SMALDI) ion source24 in which the laser spot size can be focused down to 5 μm, allowing for a pixel size down to 3 μm in diameter and enabling localization of metabolites at the single cell level6,25. Furthermore, coupling to an orbital trapping mass spectrometer allows for high mass resolution and high mass accuracy, ideal for high throughput metabolite profiling26.

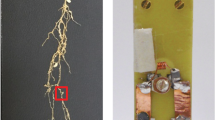

The root of Paeonia lactiflora (peony), a well-known traditional Chinese medicine, has been used for more than 1200 years in the treatment of various human diseases such as arthritis and dysmenorrhea27,28. As shown in Fig. 1, major components isolated from P. lactiflora root include monoterpene glucosides (MGs) and gallotannins29. Although pharmacological activities and chemical composition of major secondary metabolites isolated from Paeonia species have been extensively investigated, their spatial distribution in tissue are scarcely reported, in particular for gallotannins, which are a subclass of hydrolysable tannins. Tannins are known as a vital class of secondary metabolites in plant chemical defence mechanisms used for protection against pathogens, insects and herbivores30. A few histochemical staining methods have been applied for the visualization of the distribution of various tannins31. However, it should be noted that these staining methods are unable to distinguish tannins from other polyphenolic components since indicators are unspecific (based on all substrates having phenolic groups).

In the present work, spatio-chemical information on the distribution of metabolites in the root of P. lactiflora was explored by the combination of a high spatial-resolution of 10 μm and a high mass resolution of 140,000 at m/z 200. Due to the high quality of the obtained ion images, spatial contexts of individual gallotannins and monoterpenes could be revealed for the first time at the cellular level. High mass accuracy (<3 ppm root mean square error (RMSE)) and on-tissue MS/MS measurements helped in identifying metabolites. These results are in accordance with earlier histochemical studies conducted on different plant organs32,33,34, but are more detailed. Precise spatial information presented here provides significant improvement of our understanding of several key issues, regarding biosynthesis pathways as well as the deposition and transportation of tannins and monoterpenes.

Results

A representative single-pixel mass spectrum obtained from the root cross-section of P. lactiflora is shown in Fig. 2. Two major specific classes of secondary metabolites i.e. gallotannins and monoterpene glucosides (MGs), were detected as ionic adducts with sodium and potassium. Owing to the high mass resolution, it was possible to distinguish peaks with mass differences as small as of 0.02 u as shown in Fig. 2a. The identification of metabolites was based on accurate mass and/or on-tissue MS/MS measurements. At very low ion abundances, no MS/MS data but still the accurate mass of Na+ and/or K+-attached ions was available, assisting the identification of the compounds (Figs S1–S3 and Table S1).

Mass spectrum acquired from a single 30 μm pixel for mass range m/z = 400–600 (a) and m/z = 950–1600 (b) from the root cross-section of P. lactiflora. Identified compounds are labeled with measured mass, compound name, and mass deviation. See Table S1 for more details.

Visualization of the distribution of gallotannins in the root cross-section of P. lactiflora

Figure 3 shows ion images of various gallotannins visualized in the root section with a pixel size of 30 μm and 10 μm, respectively. A number of gallotannins were detected in particular at the cork layer and the xylem region including pentagalloylglucose (5GG) (m/z = 979.08134, [M + K]+), hexagalloylglucose (6GG) (m/z = 1131.09230, [M + K]+), heptagalloylglucose (7GG) (m/z = 1283.10326, [M + K]+), octagalloylglucose (8GG) (m/z = 1435.11422, [M + K]+) and nonagalloylglucose (9GG) (m/z = 1587.12517, [M + K]+). RMSE values of K+ adduct ions were calculated to be less than 2.5 ppm for each ion (Table S1). In situ MS/MS measurements were conducted for compound identification, and the specific fragments obtained were consistent with previously reported MS/MS data acquired by electrospray ionization MS in the negative ion mode35. All gallotannin ions produced abundant characteristic fragment ions including [M + K/Na-170]+, [M + K/Na-170–152]+, and [M + K/Na-170-152-170]+, corresponding to successive or simultaneous loss of gallic acids (170 Da) and galloyl groups (152 Da) (Figure S1). It should be noted that, as shown in Fig. 1a, a number of isomeric gallotannins are present in peony root, which is a challenge in the structure identification of isomers by only using accurate mass and MS/MS.

MALDI images of gallotannins in the P. lactiflora root, recorded with a scanning step size ( = pixel size) of 30 μm and 10 μm, respectively.

(a) Optical image of the ½ root and (c) confined region of interest. (b) Ion images of gallotannins at 30 μm step size and 260 × 140 pixels per image, and at (d) 10 μm step size and 360 × 140 pixels per image. All ions are displayed using the same intensity scale (Gray: 0–255). The mass accuracy was better than 2 ppm (RMSE), and a bin width of m/z = ± 5 ppm was used for image generation. Images represent the potassium adducts of the compounds listed in Table 1.

Initially, a pixel size of 30 μm was used in order to obtain an overview of the metabolite distribution in the ½ root section from cork layer to the central region, representing the anatomical features of the root (Fig. 3a,b). To obtain fine localization of metabolites at the cellular level a higher spatial resolution with 10 μm pixel size was then used to acquire ion images in a confined area (Fig. 3c,d). The distribution patterns of 5GG, 6GG, 7GG, 8GG and 9GG exhibited both regional similarities and differences. In peony root, gallotannins were commonly deposited in the cork layer and xylem regions. However, there is a gradual decrease of gallotannin pixel coverage from 5GG to 9GG in the parenchyma cells of cortex and xylem regions. This is also obvious from Table 1, regarding the reduced value of pixel coverage in both 30 μm and 10 μm spatial resolution experiments.

Visualization of the distribution of paeoniflorin and its derivatives in the root cross-section of P. lactiflora

Figure 4 shows ion images of various MGs visualized in the root section with a pixel size of 30 μm (Fig. 4b) and 10 μm (Fig. 4d), respectively. The distribution patterns of paeoniflorin and its derivatives present a high degree of similarity (Table S2). They were found mostly in the cork layer, cortex, cambium, and xylem rays. Each individual image represents putatively identified K+/Na+ adducts of paeoniflorin and its derivatives included in Table 2. Corresponding RMSE values of K+/Na+ adduct ions of the compounds were less than 1.5 ppm for each ion. Paeoniflorin (PA) and albiflorin (AL) are the two major components accumulated in amounts up to 3% in the root of P. lactiflora36. However, these two compounds are compositional isomers and therefore cannot be mass-discriminated even with ultra-high mass resolution. Both of them were detected as [M + Na]+ at m/z 503.15239 and [M + K]+ at m/z 519.12632 in positive-ion mode. On-tissue MS/MS experiments were conducted on [M + Na]+ but the common fragments obtained at m/z 381.1156 ([M-(benzoic acid) + Na]+), m/z 341.0996 ([M-glu + Na]+), m/z 219.0628 ([aglycone + Na]+) and m/z 185.0420 ([glu + Na]+) (Figure S1) made it impossible to distinguish them.

MALDI images of monoterpene glucosides in the P. lactiflora root, recorded with a scanning step size of 30 μm and 10 μm, respectively.

(a) Optical image of the ½ root and (c) confined region of interest. (b) Ion images of monoterpene glucosides at 30 μm step size and 260 × 140 pixels per image, and at (d) 10 μm step size and 360 × 140 pixels per image. All ions are displayed using the same intensity scale (Gray: 0–255). The mass accuracy was better than 2 ppm (RMSE), and a bin width of m/z = ± 5 ppm was used for image generation. Each individual image represents the K+ adducts of the compounds listed in Table 2.

For the region of interest, a high spatial resolution imaging experiment was performed with a spatial resolution of 10 μm (Fig. 4d). Highly resolved images reveal detailed morphological and chemical features. In the xylem region, heterogeneous distributions of various MGs were visualized in a sector. Relatively low intensities were detected specifically in xylem vessels and fibres. In a small well-defined region of the xylem, MGs expressed high abundances, possibly pointing to different cell types in the xylem. Preliminary studies of MG distributions were only performed on the root tissues of Paeonia moutan (tree peony)37, which belongs to the same genus Paeoniaceae as P. lactiflora but classified as section Moutan. Results from quantitative thin layer chromatography (TLC) showed that four MGs including PA, benzoyl-PA, benzoyloxy-PA and oxy-PA, mainly exist in periderm and cortex regions, but have lower abundance in xylem parts. Therefore, results presented here indicate that the biosynthesis pathways of secondary metabolites are more likely to share similar features in deposition and transportation in the same generic plants.

Visualization of the distribution of primary and other secondary metabolites in the root cross-section of P. lactiflora

Besides gallotannins and MGs, a number of additional ions, such as amino acids, carbohydrates, lipids and monoterpenes (Table 3) were putatively identified using our high resolution MSI platform. With a 10 μm spatial resolution, tissue-specific distributions of these metabolites were accurately visualized in the root (Fig. 5). For example, arginine (m/z 175.11895, [M + H]+) was found mainly in the xylem vessels and fibres, with homogenous distributions in the xylem, different from the cell-specific distributions of MGs and complex gallotannins, e.g. 8GG and 9GG (Fig. 3d). Additionally, monosaccharides (m/z 219.02655, [M + K]+), disaccharides (m/z 381.07937, [M + K]+), trisaccharides (m/z 543.13219, [M + K]+), as well as tetrasaccharides (m/z 705.18502, [M + K]+) were visualized and were found to have similar distribution patterns, with primary accumulation in the cortex and xylem rays.

MALDI images of selected primary and other secondary metabolites in the P. lactiflora root, recorded with a spatial resolution of 10 μm and 360 × 140 pixels per image.

All ions are displayed using the same intensity scale (Gray: 0–255). The mass accuracy was better than 1 ppm (RMSE), and a bin width of m/z = ± 5 ppm was used. Each individual image represents the H+/Na+/ K+ adducts of the compounds included in Table 3.

With the benefit of high mass-resolving power three ions neighbouring within a narrow mass range of 0.1 mass units, were successfully resolved and putatively identified as [benzoylsucrose + K]+ (m/z 485.10558), [lactiflorin + Na]+ (m/z 485.14182) and [pinen-10-yl-vicianoside + K]+ (m/z 485.17836). As shown in Fig. 5, lactiflorin and pinen-10-yl-β-vicianoside show similar distribution patters as PA/AL (Fig. 4d). However, [benzoylsucrose + K]+ (m/z 485.10558) shows distinct deposition sites, in contrast to [benzoylpaeoniflorin + K]+ (m/z 623.15253) (Fig. 4d), mainly accumulating in the cork layer and cambium region. Each individual image in Fig. 5 represents either H+, Na+, or K+ adducts of the compounds, as listed in Table 3.

Discussions

Unlike in well-established gene and protein analysis, deciphering the relationship between location and function of small molecules offers a great challenge, primarily due to metabolite transport between compartments and the complicated metabolic network that exists in both time and space38. With its unique ability to provide spatial information and chemical characterization, high resolution MALDI-MSI provides unparalleled chemical imaging beyond traditional staining methods, making it possible to map hundreds to thousands of components in the tissue sections of biological samples. MSI is therefore gradually gaining importance in plant science4,17. In the present work, the spatial distributions of species-specific secondary metabolites in the root of P. lactiflora were complementarily investigated at a cellular resolution for the first time, which is rather difficult to be explored with histochemical methods if no specific probes were designed for individual metabolites. MALDI imaging, however, is confined to approximately 5 μm spatial resolution, being a limitation for subcellular imaging. Additionally, localization of biosynthetic enzymes with MSI is extremely challenging due to their low abundance, degradation, and low desorption/ionization efficiencies of proteins from plant tissue sections. Therefore, microscopy-based imaging techniques are used to localize enzymes in cells and their sub-compartments. With both, high specificity and high lateral resolution of IMH methods, the deposition sites of gallotannins and ellagitannins and acyltransferase were investigated in young oak root tissues at subcellular level. It was revealed that parenchyma cell walls of cortex and endodermis cells are special accumulation sites34. However, gallotannins and ellagitannins were stained non-specifically. In contrast to other imaging techniques such as optical imaging, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), X-ray computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET), in vivo analysis is inaccessible to MALDI MSI39. Therefore, combining MSI techniques with various imaging modalities is becoming a topic of high interest to obtain more detailed spatio-chemical information on plant secondary metabolites and localization of associated biosynthetic enzymes, which will enhance the understanding of synthesis, transportation and accumulation of metabolites in plant tissues40.

A lateral resolution of 30 μm in the initial experiments was sufficient to resolve metabolite localizations, but detailed morphological features at the cellular level were unavailable (Figs 3b and 4b). Therefore, AP-MALDI imaging experiments with a higher lateral resolution of 10 μm were performed. As shown in Figs 3d and 4d, for example, cell populations in xylem rays with an approximate diameter of 30–70 μm were clearly resolved at 10 μm pixel size, well correlated to the histological question. Furthermore, subtle differences of metabolites resolved at 10 μm resolution could not be confidently justified at 30 μm resolution (Figure S4).

Current MS-based molecular imaging is mainly applied for targeted analysis, although it has great potential for global imaging of metabolites. High resolution in mass and space is a prerequisite, due to the high degree of complexity in biological tissue, whereas the identification of ions is a challenge for experiments performed with low or medium resolution mass spectrometers. Benefiting from the ultra-high mass resolving power and mass accuracy provided by orbital trapping mass spectrometers, closely neighbouring peaks with the same nominal mass (a fairly common issue in plant tissues) can be separated and the obtained accurate mass can be directly used for calculation of elemental composition and even for high fidelity mass spectra library searches. Therefore, small pixel size, high mass accuracy and mass resolution are necessarily a prerequisite for high-quality MS imaging of plant tissues.

Highly specialized metabolism in plant tissues leads to rather diverse distributions of metabolites. By overlaying optical and ion images (Fig. 6b–d) and individual ion images (Fig. 6e–g) of specific MGs and gallotannins in one composite image, similarities and differences of localization of metabolites become readily evident. As shown in Fig. 6b,c,e, in the cortex, PA/AL and 5GG share similar deposition sites, but in the xylem regions they have complementary distributions, even more pronounced in the composite image of PA/AL (B: blue) and 8GG (G: green) (Fig. 6f). Furthermore, as shown in Figs 3d and 6g, spatial localization of the homologous series of 5GG and complex gallotannins (6GG-9GG) display a rather interesting pattern in which 5GG (known as immediate precursors for the subsequent formation of complex gallotannins or ellagitannins) covers more area in the root tissue section, however, complex tannins are prone to accumulate in well-defined regions i.e. the cortex, xylem vessels and fibres. Additionally, in the cortex region a decreasing trend for the deposition of gallotannins from 5GG to 9GG is resolved as shown in Fig. 3d. With the capability of cellular imaging, subtle differences in vessels and xylem fibres were visualized with high-quality composite ion images (marked with white line in Fig. 6d–g), which may be correlated with the different stages of xylem cell differentiation. Next, mass spectral data of 6 regions of interest, selected from 10 μm and 30 μm ion images, were analyzed by principal component analysis (PCA) (Fig. 7 and Figure S5). Evaluation of PCA of 10 μm ion images allows to differentiate the regions of interest, consistent with high resolution imaging results. The xylem region 2 and 3 showed ion similarities and were totally separated from the xylem region 1 (selected from the region marked with white line in Fig. 6), as well as rays and cortex regions. For xylem region 2 and 3, ions contributing to the highest variance are complex gallotannins including m/z 1131.1 ([6GG + K]+), 1283.1([7GG + K]+) and 1435.1([8GG + K]+). For xylem region 1, rays and cortex regions, m/z 519.1([PA/AL + K]+) played the most significant role in separating from the other cell populations. The cork region was separated from other regions but shared similarities with the other areas. Therefore, the various regions can be distinguished as different groups, and in the xylem vessels and fibres (including xylem region 1, 2, 3) different cell types were found which can possibly be correlated with different stages of cell lignification. However, as shown in Figure S5 these small differences cannot be distinguished in 30 μm measurements but require the higher lateral resolution. In Figure S5, it is possible to see different populations of cells in the loadings plot, but it is apparent that there is significant overlap of the scores populations. It should be noted that in instances when the ionization of target analytes are influenced by endogenous chemical components, matrix ions, or different physical properties of the plant tissues the correlation between signal intensity and concentration is reduced. In particular, for plant tissues they impact on the lower limits of detection of the surface analytes, signal stability and reproducibility. All abovementioned issues are significant challenges that need to be overcome in further development of the technology.

Correlation of histology and ion image in a P. lactiflora root cross section at a scanning step size of 10 μm.

(a) Optical image of a region of interest. (b–d) Overlay of optical image and individual ion images including (a) m/z 519.12632 ([PA/AL + K]+), (b) m/z 979.08134 ([5GG + K]+) and (c) m/z 1435.11422 ([8GG + K]+). (e) Overlay of ion images for m/z 519.12632 (blue, [PA/AL + K]+) and m/z 979.08134 (red, [5GG + K]+). (f) Overlay of ion images for 519.12632 (blue, [PA/AL + K]+) and m/z 1435.11422 (green, [8GG + K]+). (g) Overlay of ion images for m/z 979.08134 (red, [5GG + K]+) and m/z 1435.11422 (green, [8GG + K]+). The regions presenting subtle differences in xylem were marked with a white line. All ion images were generated with a bin width of ± 5 ppm.

Regarding the function of secondary metabolites in ecological and evolutionary processes, the accumulation of gallotannins in particular in the cork and xylem regions (vessels and fibres) of P. lactiflora root can possibly be correlated to their great potential as a chemical defence barrier against enemies, as stored in the non-cytoplasmic compartments significantly reduce the risk of harming essential cytoplasmic components41. In previous studies, high amounts of tannins, including both condensed and hydrolysable tannins, have been shown to be preferably deposited in the bark area42. Moreover, ellagitannins were found to preferentially accumulate in the reaction zone of wood (secondary xylem of woody plants) and may contribute to the effectiveness of the reaction zone as an antimicrobial barrier43. Of high interest is the potential interrelationship of lignins and hydrolysable tannins which has been rarely reported44. These two classes of components share the general phenylpropanoid pathway for generation of precursors45. Xylem cell walls are the major deposition sites of lignins which have been visualized with various microscopy techniques46 and ToF-SIMS47. Therefore, the high quality ion images of hydrolysable tannins obtained in this study can possibly provide pivotal hints for understanding the physiological role of hydrolysable tannins in P. lactiflora root, for example, together with lignins to contribute to the xylem cell functions such as structural support, water conduction, or as a chemical defence barrier.

Methods

Chemicals and plant samples

Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), water (HPLC grade), acetone (HPLC grade) and 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB, 98%) were purchased from Fluka (Neu Ulm, Germany). Paeonia lactiflora roots were provided by the Botanical Garden of Justus Liebig University Giessen, Germany.

Sample preparation

The fresh roots of P. lactiflora were collected and stored at −80 °C until use. For cryo-sectioning, the roots were directly fixed on the sample holder of a cryo-microtome (HM 525 cryostat, Thermo Scientific, Dreieich, Germany), using deionized water as the adhesive. Sections of 20 μm thickness were obtained at −18 °C and thaw-mounted on regular glass slides for immediate imaging measurements or stored at −80 °C until analysis. To avoid condensation, tissue sections were dehydrated in a vacuum desiccator for ca. 5 minutes prior to matrix application. A dedicated pneumatic sprayer (SMALDIPrep, TransMIT GmbH, Giessen, Germany) was used for the uniform application of a DHB matrix solution prepared at concentrations of 30 mg/ml in acetone/water (0.1% TFA) 1:1 v/v. Matrix crystal sizes and uniformity were checked before measurements by visual inspection with an Olympus BX–40 microscope. A uniform matrix layer and crystal sizes <10 μm were obtained, as needed for a MALDI imaging experiment at high spatial resolution (Figure S6). Optical images of tissue sections were acquired before matrix application with the Olympus BX–40 microscope.

Instrumentation

All measurements were performed using the AP-SMALDI10 high-resolution MALDI imaging ion source (TransMIT GmbH, Giessen, Germany), which was operated at atmospheric pressure and coupled to a Q-Exactive Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany). The ion source includes a nitrogen laser (λ = 337 nm) operating at a repetition rate of 60 Hz. The laser beam was focused by a centrally bored objective lens to an optical diameter of 8.4 μm (1/e2 definition) and an effective ablation spot diameter of 5 μm48. For experiments at 30 μm pixel size, the laser was slightly defocused, and the laser energy was correspondingly increased in order to increase the irradiation area and thus the ion yield. For imaging at 10 μm pixel size an ablation spot diameter of 5 μm was used. For each mass spectrum, ions from 30 laser pulses were accumulated in the C-trap before being sent to the Orbitrap mass analyser. All experiments were performed in positive-ion mode with the target voltage set to + 4.3 kV.

Mass spectrometry imaging was performed in two adjacent sections at 30 μm and 10 μm spatial resolution in an area of 7800 × 4200 μm2 (260 × 140 pixels) and 3500 × 1400 μm2 (360 × 140 pixels) respectively. The measurement speed in full scan mode (scan range m/z 400–1600) was about 1.3 seconds per pixel at a mass resolution of 140,000 @ m/z 200). The step size of the sample stage was set to the desired pixel size. Internal lock-mass calibration was used, providing a mass accuracy of better than 3 ppm RMSE over the course of the entire run. MS/MS measurements for compound identification were performed by line scanning over the sample.

Data processing

Selected ion images were generated with the imaging software package MIRION49. All images were generated with a mass bin width of m/z ± 5 ppm from the exact mass. Single ion images were normalized to the highest intensity measured for each ion separately. RGB images were obtained by selecting three different mass signals for the three red-green-blue channels. The accurate mass (mc) of ions was used for image generation, mass accuracy and root mean square error (RMSE) were calculated by using formula (i), (ii) and (iii) respectively, described in supplementary method S1. Overlaid optical and ion images were generated with the open-source software MSiReader v0.0650. All images were generated using a bin width of ± 5 ppm without any normalization or interpolation.

Principal component analysis (PCA) and image similarity of paeoniflorin and its derivatives was calculated using MATLAB™ software (Mathworks, Inc., Sherborn, MA, USA and MATLAB™ (The MathWorks GmbH, Ismaning, Germany). Using MSiReader, six regions of interest determined from the optical image and ion images were extracted, producing a text file containing each pixel and its respective spectra between m/z 400–1600 binned at m/z ± 0.1. The number of pixels selected was n = 50 for 10 μm and n = 16 for 30 μm. Due to the scale of the image, the area had to be kept constant for an accurate evaluation. Using home-written MATLAB code in combination with a confidence ellipse (Douglas M. Schwarz), PCA plots with a 95% confidence ellipse were produced for each region of interest.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Li, B. et al. High-resolution MALDI mass spectrometry imaging of gallotannins and monoterpene glucosides in the root of Paeonia lactiflora. Sci. Rep. 6, 36074; doi: 10.1038/srep36074 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Wink, M. Evolution of secondary metabolites from an ecological and molecular phylogenetic perspective. Phytochemistry 64, 3–19 (2003).

Ehrhardt, D. W. & Frommer, W. B. New Technologies for 21st Century Plant Science. Plant Cell 24, 374–394 (2012).

Hegeman, A. D. Plant metabolomics—meeting the analytical challenges of comprehensive metabolite analysis. Briefings in Functional Genomics 9, 139–148 (2010).

Lee, Y. J., Perdian, D. C., Song, Z. H., Yeung, E. S. & Nikolau, B. J. Use of mass spectrometry for imaging metabolites in plants. Plant Journal 70, 81–95 (2012).

Pepperkok, R. & Ellenberg, J. High-throughput fluorescence microscopy for systems biology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7, 690–696 (2006).

Li, B., Bhandari, D. R., Janfelt, C., Römpp, A. & Spengler, B. Natural products in licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) rhizome imaged at the cellular level by atmospheric pressure Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Tandem Mass Spectrometry Imaging. The Plant Journal, 161–171 (2014).

Spengler, B. Mass Spectrometry Imaging of Biomolecular Information. Anal. Chem. 87, 64–82 (2015).

Spengler, B., Hubert, M. & Kaufmann, R. in Proceedings of the 42nd ASMS Conference on Mass Spectrometry and Allied Topics. 1041.

Schwamborn, K. & Caprioli, R. M. Molecular imaging by mass spectrometry–looking beyond classical histology. Nat Rev Cancer 10, 639–646 (2010).

Kaspar, S., Peukert, M., Svatos, A., Matros, A. & Mock, H. P. MALDI-imaging mass spectrometry - An emerging technique in plant biology. Proteomics 11, 1840–1850 (2011).

Moore, K., Lombi, E., Zhao, F.-J. & Grovenor, C. M. Elemental imaging at the nanoscale: NanoSIMS and complementary techniques for element localisation in plants. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 402, 3263–3273 (2012).

Venter, A., Nefliu, M. & Graham Cooks, R. Ambient desorption ionization mass spectrometry. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 27, 284–290 (2008).

Takáts, Z., Wiseman, J. M., Gologan, B. & Cooks, R. G. Mass Spectrometry Sampling Under Ambient Conditions with Desorption Electrospray Ionization. Science 306, 471–473 (2004).

Nemes, P., Barton, A. A. & Vertes, A. Three-dimensional imaging of metabolites in tissues under ambient conditions by laser ablation electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 81, 6668–6675 (2009).

Li, B., Hansen, S. H. & Janfelt, C. Direct imaging of plant metabolites in leaves and petals by desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Int. J. Mass spectrom. 348, 15–22 (2013).

Li, B., Bjarnholt, N., Hansen, S. H. & Janfelt, C. Characterization of barley leaf tissue using direct and indirect desorption electrospray ionization imaging mass spectrometry. J. Mass Spectrom. 46, 1241–1246 (2011).

Bjarnholt, N., Li, B., D’Alvise, J. & Janfelt, C. Mass spectrometry imaging of plant metabolites - principles and possibilities. Natural Product Reports 31, 818–837 (2014).

Korte, A., Yandeau-Nelson, M., Nikolau, B. & Lee, Y. Subcellular-level resolution MALDI-MS imaging of maize leaf metabolites by MALDI-linear ion trap-Orbitrap mass spectrometer. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 407, 2301–2309 (2015).

Jun, J. H. et al. High-Spatial and High-Mass Resolution Imaging of Surface Metabolites of Arabidopsis thaliana by Laser Desorption-Ionization Mass Spectrometry Using Colloidal Silver. Anal. Chem. 82, 3255–3265 (2010).

Takahashi, K., Kozuka, T., Anegawa, A., Nagatani, A. & Mimura, T. Development and Application of a High-Resolution Imaging Mass Spectrometer for the Study of Plant Tissues. Plant and Cell Physiology (2015).

Bhandari, D. R. et al. High resolution mass spectrometry imaging of plant tissues: towards a plant metabolite atlas. Analyst 140, 7696–7709 (2015).

Yamamoto, K. et al. Cell-specific localization of alkaloids in Catharanthus roseus stem tissue measured with Imaging MS and Single-cell MS. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113, 3891–3896 (2016).

Smith, C. A. et al. METLIN: A Metabolite Mass Spectral Database. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring 27, 747–751 (2005).

Koestler, M. et al. A high-resolution scanning microprobe matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization ion source for imaging analysis on an ion trap/Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometer. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 22, 3275–3285 (2008).

Schober, Y., Guenther, S., Spengler, B. & Römpp, A. Single Cell Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Mass Spectrometry Imaging. Anal. Chem. 84, 6293–6297 (2012).

Römpp, A. et al. Histology by Mass Spectrometry: Label-Free Tissue Characterization Obtained from High-Accuracy Bioanalytical Imaging. Angewandte Chemie-International Edition 49, 3834–3838 (2010).

Butler, L. In Plant Polyphenols Vol. 59 Basic Life Sciences (eds Hemingway, RichardW & Laks, PeterE ) Ch. 40, 693–698 (Springer US, 1992).

He, D.-Y. & Dai, S.-M. Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects of Paeonia lactiflora Pall., a traditional Chinese herbal medicine. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2 (2011).

Wu, S.-H., Wu, D.-G. & Chen, Y.-W. Chemical Constituents and Bioactivities of Plants from the Genus Paeonia. Chemistry & Biodiversity 7, 90–104 (2010).

Barbehenn, R. V. & Constabel, P. C. Tannins in plant–herbivore interactions. Phytochemistry 72, 1551–1565 (2011).

Grundhofer, P., Niemetz, R., Schilling, G. & Gross, G. G. Biosynthesis and subcellular distribution of hydrolyzable tannins. Phytochemistry 57, 915–927 (2001).

Mace, M. E. & Howell, C. R. Histochemistry and identification of condensed tannin precursors in roots of cotton seedlings. Canadian Journal of Botany 52, 2423–2426 (1974).

Gross, G. In Phytochemicals in Human Health Protection, Nutrition, and Plant Defense Vol. 33 Recent Advances in Phytochemistry (ed JohnT Romeo) Ch. 8, 185–213 (Springer US, 1999).

Grundhöfer, P. & Gross, G. G. Immunocytochemical studies on the origin and deposition sites of hydrolyzable tannins. Plant Science 160, 987–995 (2001).

Liu, E. H. et al. High-speed separation and characterization of major constituents in Radix Paeoniae Rubra by fast high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with diode-array detection and time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 23, 119–130 (2009).

Jeon, M.-H., Kwon, H.-J., Jeong, J.-S., Lee, Y.-M. & Hong, S.-P. Detection of albiflorin and paeoniflorin in Paeoniae Radix by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection. J. Chromatogr. A 1216, 4568–4573 (2009).

Tani, T. et al. Studies on moutan cortex: 5. Distribution of monoterpene glucosides in the root of Paeonia moutan from Nara Prefecture, Japan. Shoyakugaku Zasshi 34, 299–305 (1980).

Sweetlove, L. J. & Fernie, A. R. The Spatial Organization of Metabolism Within the Plant Cell. Annual Review of Plant Biology, Vol 64 64, 723–746 (2013).

Rudin, M. & Weissleder, R. Molecular imaging in drug discovery and development. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2, 123–131 (2003).

Dong, Y., Li, B. & Aharoni, A. More than Pictures: When MS Imaging Meets Histology. Trends in Plant Science.

Bernays, E. A., Driver, G. C. & Bilgener, M. Herbivores and Plant Tannins. Advances in Ecological Research 19, 263–302 (1989).

Rowell, R. M., Pettersen, R., Han, J. S., Rowell, J. S. & Tshabalala, M. A. Cell wall chemistry. Handbook of wood chemistry and wood composites, 35–74 (2005).

Barry, K. M., Davies, N. W. & Mohammed, C. L. Identification of hydrolysable tannins in the reaction zone of Eucalyptus nitens wood by high performance liquid chromatography–electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry. Phytochem. Anal 12, 120–127 (2001).

Helm, R. F., Ranatunga, T. D. & Chandra, M. Lignin-Hydrolyzable Tannin Interactions in Wood. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 45, 3100–3106 (1997).

Hahlbrock, K. & Scheel, D. Physiology and molecular biology of phenylpropanoid metabolism. Annual review of plant biology 40, 347–369 (1989).

Daniel, G. Microscope Techniques for Understanding Wood Cell Structure and Biodegradation. Secondary Xylem Biology: Origins, Functions, and Applications 309 (2016).

Saito, K. et al. Direct mapping of morphological distribution of syringyl and guaiacyl lignin in the xylem of maple by time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry. The Plant Journal 69, 542–552 (2012).

Guenther, S., Koestler, M., Schulz, O. & Spengler, B. Laser spot size and laser power dependence of ion formation in high resolution MALDI imaging. Int. J. Mass spectrom. 294, 7–15 (2010).

Paschke, C. et al. Mirion–a software package for automatic processing of mass spectrometric images. J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectrom. 24, 1296–1306 (2013).

Robichaud, G., Garrard, K. P., Barry, J. A. & Muddiman, D. C. MSiReader: An Open-Source Interface to View and Analyze High Resolving Power MS Imaging Files on Matlab Platform. J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectrom. 24, 718–721 (2013).

Acknowledgements

Financial support by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, Sp 314/13-1) is gratefully acknowledged. The authors would like to thank Mr. Holger Laake from the Botanical Garden of Justus Liebig University Giessen for arranging the samples, and appreciate associate professor Huijuan Liu from China Pharmaceutical University for helping elucidate microscopic structures of cross-section of P. lactiflora, and Joseph F. Ellis, Elizabeth K. Neumann and Sage J.B. Dunham from University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign for helping PCA analysis as well as for proofreading this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.L. performed experiments, analysed data and wrote the article. D.R.B. performed MS/MS experiments, analysed data and wrote the article. A.R. designed experiments and supported data evaluation B.S. designed experiments, optimized instrumentation and revised the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Prof. Dr. Bernhard Spengler is a consultant of TransMIT GmbH, Giessen, GERMANY. Dr. Dhaka Bhandari’s PhD work has been funded by TransMIT GmbH, Giessen, GERMANY. Dr. Bin Li and Prof. Dr. Andreas RÖmpp declare no potential conflict of interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Li, B., Bhandari, D., Römpp, A. et al. High-resolution MALDI mass spectrometry imaging of gallotannins and monoterpene glucosides in the root of Paeonia lactiflora. Sci Rep 6, 36074 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36074

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36074

This article is cited by

-

Metabolomics analysis of peony root using NMR spectroscopy and impact of the preprocessing method for NMR data in multivariate analysis

Journal of Natural Medicines (2023)

-

The application of mass spectrometry imaging in traditional Chinese medicine: a review

Chinese Medicine (2022)

-

Recent advances in proteomics and metabolomics in plants

Molecular Horticulture (2022)

-

3D-surface MALDI mass spectrometry imaging for visualising plant defensive cardiac glycosides in Asclepias curassavica

Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry (2021)

-

Impact of different post-harvest processing methods on the chemical compositions of peony root

Journal of Natural Medicines (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.