Abstract

Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) has been shown to be an independent predictor of cardiovascular diseases. Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 2 (DDAH 2) promotes the metabolism of ADMA and plays a key role in the regulation of acute inflammatory response. With the present study, we investigated the relationship between DDAH 2 polymorphisms and risk of coronary artery disease (CAD) and its association to plasma ADMA concentrations. We used the haplotype-tagging SNP approach to identify tag SNPs in DDAH 2. The SNPs were genotyped by PCR and sequenced in 385 CAD patients and 353 healthy controls. Plasma concentrations of ADMA were determined using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). A promoter polymorphism −449C/G (rs805305) in DDAH 2 was identified. Compared with the ADMA concentrations in CC genotype (0.328 ± 0.077 μmol/l), ADMA concentrations in CG + GG genotype were significantly increased (0.517 ± 0.090 μmol/l, P < 0.001). No significant associations between the −449C/G and risk of CAD were detected in the genetic models. The results of this study suggest that Genetic −499C/G polymorphism in DDAH 2 gene may affect the plasma ADMA concentrations in patients with CAD. However, it does not indicate a novel genetic risk marker for CAD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A major cause of the endothelial dysfunction is decreased bioavailability of nitric oxide (NO), a potent biological vasodilator synthesized in vascular endothelium from L-arginine by the action of endothelial NO synthase (eNOS)1,2. Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) is produced in human cells during proteolysis of methylated nuclear proteins. It acts as an endogenous inhibitor of eNOS by competing with L-arginine, and this in turn causes endothelial dysfunction and vascular disease3,4.

Although a proportion of ADMA is excreted in the urine, it has been estimated that more than 70% of ADMA is metabolized by the enzyme dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH) in vivo5. Two isoforms of DDAH have been identified and they are each encoded by genes positioned on chromosomes 1p22 and 6p21.36. DDAH 1 is typically found in tissues expressing neuronal NOS, whereas DDAH 2 predominates in tissues containing the endothelial isoform of NOS7. Although the apparent rate of ADMA metabolism for DDAH 2 is almost 70 times less than that of DDAH-1, DDAH-2 gene silencing also reduced endothelial dependent relaxation by 40% in vivo8. Recent studies established a marked cellular disparity in the expression of the two isoforms, with DDAH 2 making a predominant contribution in endothelial cells where it determines NO bioactivity9.

The aim of our study was to investigate the relationship between the DDAH 2 polymorphisms and risk of coronary artery disease (CAD) and its association to plasma ADMA concentrations in a Chinese population.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

This research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, and the experiments on human subjects were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. 385 CAD patients (255 males and 130 females, aged 32–78 years) and 353 control subjects (232 males and 121 females, aged 30–76 years) were recruited from the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University in September, 2013–March, 2016. Participants were included if they met at least one of the following three inclusion criteria: (1) Chest pain with electrocardiogram (ECG) changes and/or elevated CK-MB or cardiac troponin T/I (cTn T/I); (2) Angiographically verified CAD; (3) Stable or unstable angina along with positive Treadmill Test (TMT) or ECG ST-T changes with elevated CK-MB or cTn T/I. Patients with other severe medical conditions, pregnant women, and lactating mothers were excluded from the study. Controls for the study were sampled during the same time period. Controls were healthy volunteers, free of any signs or symptoms of cardiovascular disease. They were recruited from a geographic background similar to that of the patients and came from community samples or hospital staff. All subjects provided written informed consent prior to participation and also consented to having blood drawn at the time of angiography or time of screening for DNA extraction.

Anthropometric and Clinical Parameters

A full physical examination of all the subjects was carried out. Height and weight were recorded to the nearest 0.5 cm and 0.1 kg, respectively. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the formula kg/m2. Blood pressure was measured twice by an examining physician at an interval of 30 min using automated oscillometric device. An average value of the two readings served as the final measure of blood pressure. A diagnosis of hypertension was based on the presence of elevated systolic (≥140 mmHg) and/or diastolic (≥90 mmHg) blood pressure, or current use of antihypertensive medications. Diabetes was diagnosed when the subject met at least one of the following three criteria: 1) a random venous plasma glucose concentration ≥11.1 mmol/l; 2) a fasting plasma glucose concentration ≥7.0 mmol/l; 3) two hour plasma glucose concentration ≥11.1 mmol/l (two hours after 75 g anhydrous glucose in an oral glucose tolerance test).

Biochemical Measurements

Blood samples were drawn from all participants after overnight fasting of at least 8 hours. Serum levels of fasting blood glucose (FBG), triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TCHO), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) were determined using an automatic biochemistry analyzer (Hitachi HCP-7600, Japan).

Plasma ADMA Measurement

2 ml of venous blood from patients or healthy participants was obtained after the overnight fast before the angiography. The blood samples were centrifuged at 1,550 g for 20 min via the Centrifuge 5810R (Eppendorf, Germany). The serum was stored at −80 °C for enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA). Serum concentrations of ADMA were determined by ELISA (Cloud-Clone Corp, Houston, TX, USA). This assay employs the competitive inhibition enzyme immunoassay technique. A monoclonal antibody specific to ADMA has been pre-coated onto a microplate. A competitive inhibition reaction was launched between biotin labeled ADMA and unlabeled ADMA (standards or samples) with the pre-coated antibody specific to ADMA. After incubation, the unbound conjugate was washed off. Avidin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) was then carefully added to each microplate and incubated. The amount of bound HRP conjugate was inversely proportional to the concentration of ADMA in the sample. After addition of the substrate solution, the intensity of color developed was inversely proportional to the concentration of ADMA in the sample. The inter- and intra-assay variations were 5.4% and 3.8%, respectively.

DNA Isolation, Genetic Variant Selection and Genotyping

Genomic DNA was isolated from whole blood samples using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, USA) as per the instructions given by the manufacturer. DNA was extracted from 200 μl of whole blood using the spin columns provided. The isolated DNA was stored at −20 °C.

To better cover the common variations across the DDAH 2, the selection of genetic variants was based on the HapMap CHB (Chinese Han in Beijing) sample using the pairwise option of the Haploview version of the Tagger program. A minimum r2 = 0.8 was chosen as a threshold for all analyses. Only one tag SNP (rs707916) with a minor allele frequency >5% was genotyped within a 3.5-kb region spanning DDAH 2 on chromosome 6p21.3. A promoter variant −449C/G (rs805305) in DDAH 2 was in complete linkage disequilibrium with rs707916 (Fig. 1) and was selected for genotyping in all of the subjects studied since it has been reported to be associated with changes in plasma ADMA concentrations10,11.

The primers for DDAH 2 −449C/G (rs805305) polymorphism was: forward: 5′-GCGGAGAGAGGATGCTTAAC-3′ and reverse: 5′-ACACCTGTTGCCCCTGCT-3′. PCR conditions consisted of one cycle of 10 min at 95 °C, 36 cycles of 30 sec at 94 °C and 1 min at 65 °C, followed by 30 min at 72 °C in GeneAmp PCR 2720 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Direct sequencing of the PCR product was performed by a genomic company (Genewiz Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Suzhou, China), GeneTools software (Gene Tools, LLC, Philomath, OR, USA) was used to identify the SNPs. The position of the nucleotide sequence was based on the reference sequence obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nucleotide database. The SNP database hosted by NCBI database was used (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/).

Statistical Analysis

Values are means ± standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise specified. The distributions of the categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages, and the comparisons calculated by using chi-square test or Fisher exact test, as appropriate. Comparisons between groups for study variables were done using the unpaired student’s t test for normally distributed parameters. HWE (Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium) was calculated using a Q test with one degree of freedom12. We examined the contrast of the GG vs. CC, GG vs. CG and also examined the dominant genetic model (CC + CG vs. GG) and the recessive genetic model (CC vs. CG + GG)13,14. The association between DDAH 2 −499C/G polymorphism and risk of CAD was estimated by calculating odds ratio (OR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). Multivariate unconditional logistic regression was used to estimate ORs and 95% CIs after adjustment for age, gender, BMI, HDL-C, LDL-C, TCHO, TG, FBG, hypertension, diabetes, and smoking.

All reported P values are two-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SPSS software version 11.0 (SPSS, Chicago, USA) and Stata software version 10.0 (StataCorp, Texas, USA).

Results

Clinical Characteristics of Participants

A total of 385 CAD patients (mean age 64.21 ± 8.69; 77.1% men) and 353 controls (mean age 64.16 ± 8.58; 74.8% men) took part in the study. Clinical characteristics of all participants at baseline are summarized in Table 1. Overall, CAD patients had higher BMI, FBG, LDL-C, TG, ADMA, and higher prevalence of hypertension compared with controls (all P < 0.05). There were no differences between the groups with respect to age, gender, TCHO, HDL-C, diabetes, and smoking.

Polymorphism of DDAH 2 gene

The SNP of DDAH 2 [rs805305 (−449C/G)] was genotyped in 385 CAD patients and 353 controls. The genotypes of the SNP examined in CAD patients and controls are summarized in Table 2. The distribution of the DDAH 2 genotype in the controls was compatible with HWE (P > 0.05), with allele frequencies of 39.24% and 60.76% for the C and G alleles, respectively.

Association Between DDAH 2 Gene Polymorphism and Risk and CAD

The distribution of allele and genotype frequencies is shown by group in Table 2. We did not detect significant associations between DDAH 2 −449C/G polymorphism and risk of CAD in genetic models for GG vs. CC (OR = 0.796, 95% CI: 0.522–1.215), GG vs. GC (OR = 0.979, 95% CI: 0.711–1.348), dominant genetic model (OR = 0.925, 95% CI: 0.68–1.248), and recessive genetic model (OR = 0.806, 95% CI: 0.550–1.182).

Similar results were obtained after adjusting for confounding factors such as age, gender, BMI, HDL-C, LDL-C, TCHO, TG, FBG, hypertension, diabetes, and smoking. The associations were not significant for GG vs. CC (OR = 0.697, 95% CI: 0.406–1.195; adjusted P = 0.189), GG vs. GC (OR = 1.141, 95% CI: 0.808–1.612; adjusted P = 0.454), dominant genetic model (OR = 0.839, 95% CI: 0.572–1.232; adjusted P = 0.371), and recessive genetic model (OR = 0.846, 95% CI: 0.576–1.243; adjusted P = 0.394). See Table 3 for a list of the main results.

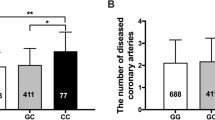

DDAH 2 Gene Polymorphism and ADMA Concentrations

There was a trend towards increasing ADMA between different DDAH 2 genotypes. ADMA was most abundant in the GG homozygotes, least abundant in the CC homozygotes and detectable at intermediate levels in the heterozygotes. When compared the ADMA concentrations in CC genotype (0.328 ± 0.077 μmol/l), the ADMA concentrations in CG + GG genotype were significantly increased (0.517 ± 0.090 μmol/l, P < 0.001, unpaired t test; Fig. 2).

Discussion

With the present study, we demonstrated that (1) the genetic polymorphism (−499 C/G rs 805305) in the DDAH 2 genes was significantly associated with plasma ADMA concentrations in participants with CAD, but (2) the polymorphism may not be related to the risk of CAD in this Chinese population.

ADMA as an endogenous inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) was characterized in the 1992 study by Vallance and coworkers15. ADMA is synthesized when arginine residues in proteins are methylated by the action of protein arginine methyltrans ferases. Humans generate approximately 300 μmol of ADMA per day16. The clearance of ADMA from the body is either by excretion in the urine or by metabolism. A number of cells that generate ADMA can also inactivate it by metabolizing it to citrulline, in a reaction catalyzed by the enzyme DDAH17. ADMA inhibits the three isoforms of NOS and is equipotent with L-NMMA. High levels of circulating ADMA have been shown to impair NO dependent functions in the vascular wall. It can also uncouple the enzyme, generate super-oxides, and it has been linked to endothelial dysfunction18. In previous studies, we demonstrated that the increased ADMA levels directly cause endothelial dysfunction by down-regulating mRNA and protein expression of eNOS, decreasing the generation of NO, increasing superoxide production, and inducing endothelial apoptosis in human internal mammary arteries as well as in porcine coronary arteries19,20.

Numerous studies have demonstrated a relationship between high ADMA concentrations and cardiovascular diseases21. Elevated ADMA has a high prevalence in hypercholesterolemia, hyperhomocysteinemia, diabetes mellitus, peripheral arterial occlusive disease, hypertension, chronic heart failure, and other diseases22,23,24,25,26,27. In our recent meta-analysis involving 2,939 CAD patients and 1,774 controls, we found that high ADMA levels are a risk factor in patients with CAD (P = 1.16 e–7). The subgroup analysis also indicated that increased ADMA levels were detected in different clinical types of CAD, including myocardial infarction (P = 0.006), stable angina pectoris (P = 0.020), and unstable angina pectoris (P = 0.003)28. With the present results, we also demonstrate significantly higher plasma ADMA concentrations in CAD patients (0.481 ± 0.115 μmol/l) compared to controls (0.459 ± 0.090 μmol/l, P = 0.003).

ADMA is actively metabolized by DDAH, which is expressed as two isoforms. The major difference between the two isoforms is tissue expression pattern. DDAH 1 is widely expressed, especially in liver and kidney at sites of NOS expression. DDAH 2 is expressed at relatively high levels in all fetal tissues, while in adults, concentrations fall and sites of expression become more selective. DDAH 2 predominates in the vascular endothelium, which is the site of eNOS expression9. DDAH 2 localizes to 6p21.3, a region which contains many genes involved in the immune and inflammatory responses, and has been linked with susceptibility to several autoimmune diseases. This localization and its wide expression in immune cells suggest that DDAH 2 has the potential to be a disease-susceptibility gene6. However, the role of DDAH 2 in ADMA metabolism and cardiovascular disease remains controversial. Wang and co-workers demonstrated that DDAH 2 gene silencing had no effect on plasma ADMA in a rat sample29. In contrast, results of other studies indicated that DDAH 2 genetic variations were significantly associated with serum ADMA concentrations, especially in human samples10,11. We present the novel finding that the CAD patients carrying the G alleles of DDAH 2 gene −499 C/G have higher plasma ADMA concentrations.

The DDAH 2 gene −499 C/G polymorphism has been linked with the risk of a number of cardiovascular diseases, including type 2 diabetes, hypertension, intracerebral hemorrhage, and hemodynamic shock among others30,31,32. However, there are comparatively few studies, most with small sample sizes, examining the relationship between the polymorphism and risk of CAD. GAD and colleagues demonstrated that the G allele of DDAH 2 gene −499 C/G polymorphism is an important risk factor in male 35–50 year-old Egyptian CAD patients (100 CAD patients vs. 100 healthy controls)33. However, Xu and colleagues indicated that no association was observed between the DDAH 2 polymorphisms and risk of CAD (180 Chinese CAD patients vs. 180 healthy controls)34. The present study evaluated the association between the polymorphism and risk of CAD in a large sample of 738 participants (385 cases and 353 controls). We failed to find a significant association in this Chinese population. Similar results were obtained after adjusting for confounding factors such as age, gender, BMI, HDL-C, LDL-C, TCHO, TG, FBG, hypertension, diabetes, and smoking. To our knowledge, DDAH 2 not only directly affects plasma ADMA concentrations, but also has an important role in cellular differentiation or cell cycle control processes in which NO is involved35,36. Future studies should address other mechanisms of DDAH 2 gene with regard to the risk of CAD, including methylation.

In conclusion, genetic polymorphism (−499C/G, rs805305) in DDAH 2 gene was found to be significantly associated with plasma ADMA concentrations in patients with CAD. However, our findings suggest that the DDAH 2 variant is not a novel genetic risk marker for CAD.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Xuan, C. et al. Dimethylarginine Dimethylaminohydrolase 2 (DDAH 2) Gene Polymorphism, Asymmetric Dimethylarginine (ADMA) Concentrations, and Risk of Coronary Artery Disease: A Case-Control Study. Sci. Rep. 6, 33934; doi: 10.1038/srep33934 (2016).

References

Förstermann, U. & Li, H. Therapeutic effect of enhancing endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) expression and preventing eNOS uncoupling. Br J Pharmacol. 164, 213–223 (2011).

Gluba, A., Banach, M., Mikhailidis, D. P. & Rysz, J. Genetic determinants of cardiovascular disease: the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, paraoxonases, endothelin-1, nitric oxide synthase and adrenergic receptors. In Vivo 23, 797–812 (2009).

Chan, N. N. & Chan, J. C. Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA): a potential link between endothelial dysfunction and cardiovascular diseases in insulin resistance syndrome. Diabetologia 45, 1609–1616 (2002).

Banach, M. et al. Lipids, blood pressure and kidney update 2015. Lipids Health Dis. 14, 167 (2015).

Achan, V. et al. Asymmetric dimethylarginine causes hypertension and cardiac dysfunction in humans and is actively metabolized by dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 23, 1455–1459 (2003).

Tran, C. T., Fox, M. F., Vallance, P. & Leiper, J. M. Chromosomal localization, gene structure, and expression pattern of DDAH1: comparison with DDAH2 and implications for evolutionary origins. Genomics 68, 101–105 (2000).

Tran, C. T., Leiper, J. M. & Vallance, P. The DDAH/ADMA/NOS pathway. Atheroscler Suppl. 4, 33–40 (2003).

Pope, A. J., Karuppiah, K. & Cardounel, A. J. Role of the PRMT-DDAH-ADMA axis in the regulation of endothelial nitric oxide production. Pharmacol Res. 60, 461–465 (2009).

Palm, F., Onozato, M. L., Luo, Z. & Wilcox, C. S. Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH): expression, regulation, and function in the cardiovascular and renal systems. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 293, H3227–H3245 (2007).

O’Dwyer, M. J. et al. Septic shock is correlated with asymmetrical dimethyl arginine levels, which may be influenced by a polymorphism in the dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase II gene: a prospective observational study. Crit Care 10: R139 (2006).

Abhary, S. et al. Sequence variation in DDAH1 and DDAH2 genes is strongly and additively associated with serum ADMA concentrations in individuals with type 2 diabetes. PLoS One. 5, e9462 (2010).

Xuan C. et al. Association Between MTHFR Polymorphisms and Congenital Heart Disease: A Meta-analysis based on 9,329 cases and 15,076 controls. Sci Rep. 4, 7311 (2014).

Xuan C. et al. PTPN22 Gene Polymorphism (C1858T) Is Associated with Susceptibility to Type 1 Diabetes: A Meta-analysis of 19,495 Cases and 25,341 Controls. Ann Hum Genet 7, 191–203 (2013).

Xuan, C., Bai, X. Y., Gao, G., Yang, Q. & He, G. W. Association between polymorphism of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677T and risk of myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis for 8,140 cases and 10,522 controls. Arch Med Res. 42, 677–685 (2011).

Vallance, P., Leone, A., Calver, A., Collier, J. & Moncada, S. Endogenous dimethylarginine as an inhibitor of nitric oxide synthesis. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 20, S60–S62 (1992).

Achan, V. et al. Asymmetric dimethylarginine causes hypertension and cardiac dysfunction in humans and is actively metabolized by dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 23, 1455–1459 (2003).

Fogarty, R. D. et al. Relationship between DDAH gene variants and serum ADMA level in individuals with type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes Complications 26, 195–198 (2012).

Antoniades, C. et al. Association of plasma asymmetrical dimethylarginine (ADMA) with elevated vascular superoxide production and endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling: implications for endothelial function in human atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J. 30, 1142–1150 (2009).

Xuan C. et al. L-citrulline for protection of endothelial function from ADMA-induced injury in porcine coronary artery. Sci Rep. 5, 10987 (2015).

Xuan C. et al. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase enhancer for protection of endothelial function from asymmetric dimethylarginine-induced injury in human internal thoracic artery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 144, 697–703 (2012).

Serban, C. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of statins on plasma asymmetric dimethylarginine concentrations. Sci Rep. 5, 9902 (2015).

Mittermayer, F. et al. Asymmetric dimethylarginine predicts major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with advanced peripheral artery disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 26, 2536–2540 (2006).

Krzyzanowska, K., Mittermayer, F., Wolzt, M. & Schernthaner, G. Asymmetric dimethylarginine predicts cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 30, 1834–1839 (2007).

Dückelmann, C. et al. Asymmetric dimethylarginine enhances cardiovascular risk prediction in patients with chronic heart failure. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 27, 2037–2042 (2007).

Tsioufis, C. et al. ADMA, C-reactive protein, and albuminuria in untreated essential hypertension: a cross-sectional study. Am J Kidney Dis. 55, 1050–1059 (2010).

Maas, R. et al. Asymmetrical dimethylarginine (ADMA) and coronary endothelial function in patients with coronary artery disease and mild hypercholesterolemia. Atherosclerosis 191, 211–219 (2007).

Dayal, S. & Lentz, S. R. ADMA and hyperhomocysteinemia. Vasc Med. 10, S27–S33 (2005).

Xuan, C. et al. Levels of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), an endogenous nitric oxide synthase inhibitor, and risk of coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis based on 4713 participants. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 23, 502–510 (2016).

Wang, D. et al. Isoform-specific regulation by N(G),N(G)-dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase of rat serum asymmetric dimethylarginine and vascular endothelium-derived relaxing factor/NO. Circ Res. 101, 627–635 (2007).

Seo, H. A. et al. Association of the DDAH2 gene polymorphism with type 2 diabetes and hypertension. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 98, 125–131 (2012).

Bai, Y. et al. Common genetic variation in DDAH2 is associated with intracerebral haemorrhage in a Chinese population: a multi-centre case-control study in China. Clin Sci (Lond). 117, 273–279 (2009).

Weiss, S. L. et al. Pilot study of the association of the DDAH2 -449G polymorphism with asymmetric dimethylarginine and hemodynamic shock in pediatric sepsis. PLoS One 7, e33355 (2012).

Gad, M. Z., Hassanein, S. I., Abdel-Maksoud, S. M., Shaban, G. M. & Abou-Aisha, K. Association of DDAH2 gene polymorphism with cardiovascular disease in Egyptian patients. J Genet 90, 161–163 (2011).

Xu, A. G. et al. Association study of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 2 gene polymorphisms and coronary heart disease. Mol Med Rep. 6, 1103–1106 (2012).

Peunova, N. & Enikolopov, G. Nitric oxide triggers a switch to growth arrest during differentiation of neuronal cells. Nature 375, 68–73 (1995).

Dugas, N. et al. Role of nitric oxide in the anti-tumoral effect of retinoic acid and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on human promonocytic leukemic cells. Blood 88, 3528–3534 (1996).

Acknowledgements

The work was fully supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81301485 & No. 81672073), Shangdong Young Scientists Award Foundation (No. BS2013YY036), and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2016M590620).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design of the study: C.X., G.-W.H. and L.-M.L. Acquisition of sample: L.-Q.X., Q.-W.T. and H.L. Analysis and interpretation of the data: Q.W. and G.-W.H. Writing and revision of the manuscript: C.X, L.-M.L. And G.-W.H. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Xuan, C., Xu, LQ., Tian, QW. et al. Dimethylarginine Dimethylaminohydrolase 2 (DDAH 2) Gene Polymorphism, Asymmetric Dimethylarginine (ADMA) Concentrations, and Risk of Coronary Artery Disease: A Case-Control Study. Sci Rep 6, 33934 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep33934

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep33934

This article is cited by

-

Activation of arginase II by asymmetric dimethylarginine and homocysteine in hypertensive rats induced by hypoxia: a new model of nitric oxide synthesis regulation in hypertensive processes?

Hypertension Research (2021)

-

A functional variant of the dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase-2 gene is associated with myocardial infarction in type 2 diabetic patients

Cardiovascular Diabetology (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.