Abstract

Ecosystem boundary retreat due to human-induced pressure is a generally observed phenomenon. However, studies that document thresholds beyond which internal resistance mechanisms are overwhelmed are uncommon. Following the Deepwater Horizon (DWH) oil spill, field studies from a few sites suggested that oiling of salt marshes could lead to a biogeomorphic feedback where plant death resulted in increased marsh erosion. We tested for spatial generality of and thresholds in this effect across 103 salt marsh sites spanning ~430 kilometers of shoreline in coastal Louisiana, Alabama and Mississippi, using data collected as part of the natural resource damage assessment (NRDA). Our analyses revealed a threshold for oil impacts on marsh edge erosion, with higher erosion rates occurring for ~1–2 years after the spill at sites with the highest amounts of plant stem oiling (90–100%). These results provide compelling evidence showing large-scale ecosystem loss following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. More broadly, these findings provide rare empirical evidence identifying a geomorphologic threshold in the resistance of an ecosystem to increasing intensity of human-induced disturbance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human-driven environmental changes such as global warming, pollution, overharvesting and acidification have increased the amount and number of stressors ecosystems experience, leading to large declines in many marine, freshwater and terrestrial communities1,2. The response of ecosystems to these stressors varies from strong resistance to drastic declines in habitat coverage to transformation into an alternate stable state3,4,5. In the southeastern United States, for example, the combination of extreme drought and intensified consumer grazing pressure has generated threshold levels of stress and subsequent die-off of large areas of marsh plant communities6. The system has recovered in most areas, however and has not transitioned into an alternate stable state, most likely because powerful positive interactions and spatial processes facilitate plant recolonization of denuded tidal flats7.

One key to conserving and protecting these threatened ecosystems is to identify and guard against the exceedance of ecosystem thresholds – the point at which a small change in an environmental stressor produces a cascading decline in ecosystem cover and health8. Although a significant body of theoretical and modeling evidence suggests that thresholds in ecosystem resistance to disturbance are likely to occur in many habitats9, empirical data that link these inflection points to specific levels of large-scale disturbances are rare (but see ref. 10).

For many estuarine ecosystems, especially those governed by biogeomorphic feedbacks, habitat edges are the nexus for ecosystem growth and decline. Both biotic and abiotic stressors, such as consumer fronts11 and wave stress12, are typically concentrated at habitat edges and these edges are often the primary point of habitat decline if the edge is in retreat13,14. In the Gulf of Mexico, for example, extremely rapid marsh loss (40 km2 yr−1 from 1985 to 2010)15 is driven by the synergistic impacts of decreased sedimentation from land-use change and river channelization, subsidence-enhanced relative sea-level rise and changes in hydrologic connectivity16,17. Marsh edge erosion rates are particularly high in these areas18, raising concern as to how an already stressed system may respond to a major disturbance.

In the summer of 2010, oil released from the DWH disaster was found on more than 700 km of salt marsh shorelines across the Gulf of Mexico19. Given the microtidal regime of the Gulf, this oil was generally most concentrated along the marsh edge, often visible as a black belt along the shoreline that was ~5–15 meters in width3. Oiling of marshes from the DWH spill thus created a concentrated disturbance on the ecosystem’s already stressed edge. Field studies at a limited number of sites indicated that heavy levels of oiling led to elevated erosion rates, most likely because plant death resulted in decreased soil strength and reduced resistance to wave erosion3,4,20,21. A substantial amount of the marsh shoreline oiling, however, was characterized as light to intermediate19 and little is known about the impact of oiling on marsh edge erosion across a range of oiling levels.

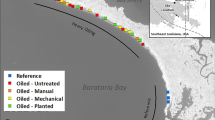

In this study, we examined the relationship between plant stem oiling and marsh erosion rates Gulf-wide to test for thresholds in the functional relationship between degree of plant oiling and erosion rates. We analyzed data collected for the Coastal Wetland Vegetation (CWV) survey as part of the NRDA process22. Data were collected across 103 sites (Fig. 1) across the states of Louisiana, Alabama and Mississippi and spanning 5 categories of oiling defined by the percentage of stem height oiled (0%, 0.1–10%, 10.1–50%, 50.1–90% or 90.1–100%; here after, 0%, 0–10%, 10–50%, 50–90%, 90–100%). At each site, cumulative erosion was monitored based on field surveys of marsh retreat relative to a datum established in fall 2010 (Louisiana sites) or spring 2011 (Alabama and Mississippi sites) and remeasured in fall 2011, fall 2012 and fall 2013. As previous field experiments have shown that: (1) accelerated erosion rates are associated with belowground plant mortality3 and (2) mortality of both aboveground23 and belowground biomass3,24 are pronounced at the heaviest oiling levels, our hypotheses were that erosion rates would be positively correlated with degree of plant oiling and that this response might exhibit threshold behavior at the highest (90–100%) stem oiling level.

Map of all survey sites.

Figure created using ArcGIS, 10.3, (http://desktop.arcgis.com/en/arcmap/).

Results

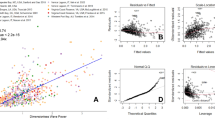

Analyzing all sites across the three states in spring 2011 and fall 2013 (total sample sizes ranged from 96 to 103 sites; see Methods), we detected differences in erosion rate among the stem oiling levels (Kruskal-Wallis; p = 0.0021). Specifically, the total erosion in marshes with 90–100% stem oiling was more than three times higher than in marshes with no stem oiling (Fig. 2A; Table S1A). When we accounted for potential confounding effects of variation in wave exposure among marsh sites, the mean erosion rate in the 90–100% stem oiling level was 1.4 m/yr higher than expected, while the mean erosion rates in the other four stem oiling levels were lower than expected (Fig. 2B; Table S1B). Examination of annualized erosion rates revealed that erosion at sites with the highest stem oiling levels was 3.4 m/yr larger than expected (p = 0.027) during the 2011–2012 survey period, but was indistinguishable from other oiling levels during 2012–2013 (Fig. 2C; Table S2).

(A) Box plots of unadjusted erosion rates (m/yr) in each stem oiling category for all sites. (B) Mean excess erosion (m/yr) for each stem oiling category. Excess erosion is the difference between the observed mean erosion for that stem oiling category and the expected mean wave-adjusted erosion rate if there were no differences in erosion among the stem oiling categories. The vertical lines are the central 95% randomization distributions for excess erosion in each stem oiling category. When the vertical line does not cross 0, the p-value for the comparison of that stem oiling category to the overall erosion rate is less than 0.05. (C) Mean excess erosion (m/yr) by stem oiling category in 2011–2012 and 2012–2013 for all sites. Symbols as in Fig. 2B. (D) Box plot comparing total belowground biomass between the 0% and 90.1–100% oiling categories in CWV plots nearest to the marsh edge in Fall 2010.

We observed the same patterns when the analysis was restricted only to sites in Louisiana, which had a longer sampling period and comprised the majority of our study sites (see Methods). The mean cumulative (2010–2013) erosion rate in the 90–100% stem oiling level was 4.0 m/yr, significantly higher than mean erosion rates of 1.4 to 2.1 m/yr in the other oiling levels (Kruskal-Wallis; p = 0.033; Figure S1A). After adjustment for wave energy, the erosion rate in the 90–100% stem oiling level was 1.6 m/yr more than expected, but this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.13). Using just the Louisiana sites, on a year-by-year basis, mean wave-adjusted erosion rates in the highest stem oiling level were 1.6 m/yr higher than expected from fall 2010–fall 2011 (p = 0.040; Figure S2, Table S4). For fall 2011–fall 2012, the difference was 3.0 m/yr (p = 0.068). By the third year of the study (fall 2012–fall 2013), erosion rates for the highest oiling level were no longer elevated relative to the other levels.

To evaluate whether accelerated erosion at high stem oiling sites was correlated with loss of belowground biomass at those sites, we compared total belowground biomass in unoiled vs heavily oiled sites for the fall 2010 sampling event. This sampling date in 2010 was ~5 months after the oiling occurred, but before heavily oiled marsh edges were lost to erosion and the marsh platform lowered to elevations where marsh plants drown3,23. In fall 2010, the mean total belowground biomass in the sites with the heaviest (90–100%) stem oiling was approximately 13,000 g/m3, ~30% lower than the mean total belowground biomass in the unoiled sites (~19,000 g/m3, p = 0.036; Fig. 2D). Because the NRDA protocol for measuring total belowground biomass included both live and dead root material, this analysis should be considered a conservative estimate of how oiling influenced the live plant roots that are critical for providing soil strength in these environments. Another recent study24 that evaluated live belowground biomass as a function of qualitative oiling severity found significant reductions in live belowground biomass at the heaviest oiling levels.

Consistent with field evidence for reduced belowground biomass following the DWH spill, a meta-analysis of seven published studies investigating oiling impacts on Spartina spp. also revealed a consistent pattern of negative impacts of heavy oiling on belowground plant biomass. Averaged across all studies, we found a significantly negative effect of oiling on Spartina spp. belowground biomass (Hedges’ g = −1.379, 95% CI = −1.99 to −0.77, P < 0.0001; Fig. 3).

Meta-analysis results testing for the mean effect of oiling on Spartina spp. belowground biomass.

The mean effect size (Hedges’ g ± 95% CI) are reported, with negative values indicating negative effects of oiling on belowground biomass. 95% CI that do not overlap with the zero line indicate significant effects.

Discussion

The results of our regional-scale analysis reveal that accelerated marsh erosion reported in small-scale studies3,20,25 after the DWH spill also occurred extensively across the larger area of impacted coastal marshes. We observed this effect even when erosion rates were adjusted to correct for the effects of wave exposure on marsh edge erosion. Our analysis across the full range of stem oiling levels further demonstrated that Gulf Coast salt marsh ecosystems exhibited a threshold behavior in response to increasing oil disturbance: there was no observable difference in erosion rate relative to unoiled marshes at the low to moderately high stem oiling levels, but statistically significant increases in erosion rate at the highest stem oil levels (90–100% stem oiling). Because past experimental transplant studies at similarly eroded areas along marsh edges have shown that marsh plants cannot regrow due to inundation stress (i.e., after erosion the marsh platform goes from being intertidal to being primarily submerged)3, it is very likely that these disturbance-enhanced erosion rates have led to irreversible land loss along affected marsh edges of the Gulf of Mexico. However, to fully assess whether a tipping point and not just a threshold was reached, we suggest that plant recovery patterns at these sites should be further monitored.

It is very likely that the death of belowground plant material at the highest levels of stem oiling triggered the observed increases in erosion rate at the heavily oiled sites. This contention is supported by: 1) past studies that demonstrate reductions in soil strength and/or irreversible marsh platform erosion when the belowground root network is compromised on eroding marsh edges3,24; 2) previous studies that have documented significant die-back of belowground plant material as a result of heavy oiling, as revealed in our meta-analysis; and 3) vegetation survey results from the CWV survey that evince a significantly negative effect of heavy oiling on both aboveground23 and belowground biomass (Fig. 2D). The high level of resistance these marshes displayed to oil-induced, elevated erosion is predicted by past studies that have assessed potential for oiling impacts with small-scale oil addition studies in wetlands25,26. In these studies, belowground plant material – which is anticipated to be the key component underlying the protective effects of marshes – was resilient to oiling and only exhibited complete mortality in heaviest oiling treatments – a pattern we also observed in our study.

The combination of our regional-scale survey results with many small-scale, comparative studies indicating that the presence of live belowground plant material reduces erosion stress along marsh edges, challenges a recent experimental study27, which concluded that wetland plants do not protect against shoreline erosion. Resolving whether the wetland-protective paradigm is indeed robust, as suggested by the results of our large-scale survey, or should be reconsidered, as suggested by this experimental study27, will require further experimental studies conducted at larger scales that test for context dependency of plant protective effects and the relative contribution of belowground and aboveground plant material to any effect detected.

Approximately 18 months after the DWH spill, the increased erosion rates in the highest stem oiling level were no longer detected. This observed cessation of elevated erosion rates is consistent with results from a more process-oriented, but smaller scale study of the impacts of heavy oiling on shoreline erosion rates following the DWH disaster3. It is also consistent with plant health observations23,26,28,29, where the majority of significant reductions to plant health and productivity due to oiling occurred through 2012. Return to background erosion rates thus likely occurred as the erosive front intersected live root mats generated from re-growing and/or surviving areas of marsh plants that were not as severely impacted by oiling. This cessation of elevated erosion rates does not erase the accelerated and permanent loss of marshes that occurred for ~ 1.5 years.

Conclusions

Our results provide regional-scale evidence of a threshold in oil impact beyond which the resilience of salt marsh ecosystems was compromised, leading to large-scale land loss in the Gulf of Mexico, with a strong potential for irreversible ecosystem collapse, i.e. a tipping point. The resistance threshold of marshes to oil-induced, elevated erosion rates was high, non-linear and occurred at 90–100% stem oiling. This high level of resistance was likely driven by the demonstrated tolerance of belowground plant material to light and moderate levels of oiling. Empirical data such as these that identify levels of stress at which an ecosystem’s threshold to disturbance occurs are uncommon, but are critical to understand to better protect and restore valuable coastal systems in the face of global environmental change30. Given the elevated importance of salt marshes as part of a first line of defense against the rising seas6,31,32, our study highlights the need for a more robust understanding of salt marsh edge dynamics and their interactions with intensifying human-induced stressors.

Materials and Methods

Field methods

The CWV survey included multiple types of marsh. Here, we analyzed erosion data only from mainland herbaceous marshes, as 1) our previous experimental and comparative studies were also conducted in mainland herbaceous marshes3,23, 2) this marsh type was commonly impacted by oiling and 3) using one marsh type controlled as much as possible for many biotic and abiotic conditions that can vary across different types of wetlands in this region (e.g. salinity, plant species and tidal range). Mainland herbaceous marshes sampled during the CWV study were located primarily along the inland edges of protected bays and estuaries and were dominated by Spartina alterniflora in Louisiana23 and co-dominated by Juncus roemerianus and S. alterniflora in Mississippi and Alabama28. The initial CWV survey of Louisiana marsh sites was conducted based on a stratified random sample of 78 sites from a collection of 713 marsh pre-assessment survey sites23. One of the 78 CWV sites was missing data in fall 2012 and fall 2013; the final Louisiana dataset described here therefore included 77 of the 78 CWV sites. Seven of the Louisiana sites were missing erosion data in spring 2011.

The initial CWV dataset, established during fall 2010, was supplemented in spring 2011 with 26 sites in Mississippi and Alabama, which were selected from an additional 114 pre-assessment sites in those states. Four of these sites were missing data in fall 2011. The complete three-state CWV database contained a total of 103 sites, although some analyses were based on a slightly smaller sample sizes because of the missing values. In all cases, strata were defined by the extent of stem oiling observed during the pre-assessment survey (0%, 0.1–10%, 10.1–50%, 50.1–90% and 90.1–100%), which occurred between late May and early September of 201023,28.

Measurements of marsh edge position were made at all sites in fall 2011, fall 2012 and fall 2013. We focused our analysis on annual and cumulative erosion between spring 2011 and fall 2013 at all sites in the CWV survey, because this was the longest period with data from all three states. We also analyzed annual erosion from fall 2010 to fall 2013 for the Louisiana sites, which provides additional insight into the effects of oiling on erosion in the first six months following the spill.

At each site, survey teams established marsh edge and inland stakes using polyvinyl chloride (PVC) poles to demarcate the beginning and end of a line transect perpendicular to the shoreline. The shoreline stake was placed at the marsh edge and the inland stake was placed at the furthest inland point of oiling documented either during the pre-assessment survey or transect installation. At unoiled reference sites, the inland stake was placed at 20 m inland from the marsh edge. On each sampling date, survey teams measured the distance from the inland stake to the current marsh edge to determine cumulative erosion. Complete details on the CWV survey design and field observations can be found in (ref. 22).

In order to account for effects of incident wave energy on erosion rates, we used a measure of relative wind-wave exposure that was quantified for each of the sites33,34. This metric, referred to as the mean wave exposure index, is calculated from the product of average wind speed and fetch along each of 8 cardinal directions. A detailed description of how the wave exposure index was calculated can be found in ref. (34).

Erosion data analysis

Differences in marsh erosion rate among stem oiling levels were evaluated using Kruskal-Wallis tests34 and the analysis of means36,37. The Kruskal-Wallis test evaluates any difference between stem oiling levels, whereas the analysis of means detects whether one group differs from the others. Both methods are non-parametric procedures because the data did not meet the normality or equal variance assumptions of analysis of variance (ANOVA). For the Kruskal-Wallis statistic, Ri and ni were the average rank and sample size for each stem oiling level, respectively. The analysis of means36 compares the erosion rate for each stem oiling level to the overall erosion rate in all sites. The nonparametric version of analysis of means37 is based on ranks for each stem oiling level. The null distribution of the test statistic was evaluated by randomization, using 9999 randomizations of stem oiling values to erosion values. Differences were considered significant at the level P < 0.05. No adjustment for multiple testing was made because of the a-priori expectation that the differences would be largest in the 90–100% stem oiling level.

To address the influence of variation in wave exposure among marsh sites, we repeated these analyses after grouping observations by similar wave energy. This approach is an extension of the Skillings-Mack method38. Breakpoints between wave energy groups were set at the deciles of mean wave energy, giving 10 groups. Measured erosion rates were then ranked within each wave energy group. We computed the mean and median erosion in each stem oiling level and compared those values to distributions obtained by randomly reassigning erosion values to stem oiling levels within each wave energy group. Mean excess erosion for each stem oiling level was computed as the difference between the mean observed erosion and the mean of the randomly reassigned erosion values. P-values and 95% confidence intervals for excess erosion were obtained by randomly permuting erosion values within each wave-energy block using 9999 randomizations. We repeated the analysis using 5 and 15 groups of wave energy. Our results were insensitive to the number of wave energy groups, so we present here only the results from analyses using 10 wave energy groups.

Effects of oiling on belowground biomass

The CWV sampling design did not partition total belowground biomass into live and dead components. Thus we do not have direct observational evidence of the impact of oiling on live belowground biomass. In an effort to address this data gap, we followed two approaches. First, we summarized the effects of heavy oiling on total belowground biomass as measured in the CWV study. The belowground biomass in control and heavily oiled Louisiana sites was compared using a t-test. Because one CWV site outside of Louisiana was heavily oiled and there was a regional trend in belowground biomass, we only analyzed belowground biomass in Louisiana. Since total belowground biomass included both live and dead components, this analysis provides a conservative estimate of how oiling might have influenced the live plant roots that are important to soil strength in these habitats. In addition, we conducted a meta-analysis of published observational and experimental studies investigating oiling v. control differences in belowground biomass of the marsh plant genus Spartina. We used a Web of Science literature search from September 16, 2015 to assemble the existing studies investigating oiling impacts on Spartina belowground biomass using the following search criteria: TS = Spartina AND oil* or oil spill* AND belowground. Our Web of Science search generated 122 publications and out of those we narrowed the total number of studies to six3,39,40,41,42 that included oil impacts to Spartina belowground biomass by either measuring plant live belowground biomass or plant total (i.e., live + dead) belowground biomass. Although our objective was to evaluate the effect of oiling on live belowground biomass, we believe our inclusion of studies that measured total belowground biomass also makes our meta-analysis conservative, since these studies may underestimate the effect of oiling on live biomass. One study41 investigated two species of Spartina, generating a total sample size of n = 7.

For each study, we extracted the mean Spartina belowground biomass for oiled and unoiled treatments, along with the standard deviation and sample size. We then used the extracted data to measure the standardized effect size by calculating Hedges’ g43 using the metafor package44 in R45. A negative Hedges’ g value where the 95% CI did not overlap zero indicates as significantly negative effect from oiling. We determined the overall mean effect across all studies using a random-effects model. When studies used multiple treatments (e.g., unoiled, light, medium and high oiling) we used only the endpoint treatments (i.e., no oiling and high oiling) to look at the maximum possible effects. When multiple core depths were used as a factor in a single study we only used belowground responses of the shallowest layers because we assumed that oiling would have the greatest impact at shallower sediment depths.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Silliman, B. R. et al. Thresholds in marsh resilience to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Sci. Rep. 6, 32520; doi: 10.1038/srep32520 (2016).

References

Dale, V. H. et al. Climate change and forest disturbances. Bioscience 51, 723–734 (2001).

Wilson, S. K., Graham, N. A. J., Pratchett, M. S., Jones, G. P. & Polunin, N. V. C. Multiple disturbances and the global degradation of coral reefs: are reef fishes at risk or resilient? Glob. Change Biol. 12, 2220–2234 (2006).

Silliman, B. R. et al. Degradation and resilience in Louisiana salt marshes after the BP – Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 11234–11239 (2012).

Mendelssohn, I. A. et al. Oil impacts on coastal wetlands: implications for the Mississippi River Delta ecosystem after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Bioscience 62, 562–574 (2012).

Folke, C. et al. Regime shifts, resilience and biodiversity in ecosystem management. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 35, 557–581 (2004).

Silliman, B. R., van de Koppel, J., Bertness, M. D., Stanton, L. E. & Mendelssohn, I. A. Drought, snails and large-scale die-off of southern US salt marshes. Science 310, 1803–1806 (2005).

Angelini, C. & Silliman, B. R. Patch size-dependent community recovery after massive disturbance. Ecology 93, 101–110 (2012).

Côté, I. M. & Darling, E. S. Rethinking ecosystem resilience in the face of climate change. PLoS Biol. 8, e1000438 (2010).

Dodds, W. K., Clements, W. H., Gido, K., Hilderbrand, R. H. & King, R. S. Thresholds, breakpoints and nonlinearity in aquatic ecosystems as related to management. J. North Am. Benthol. Soc. 29, 988–997 (2010).

Steneck, R. S. et al. Kelp forest ecosystems: biodiversity, stability, resilience and future. Environ. Conserv. 29, 436–459 (2002).

Silliman, B. R. et al. Consumer fronts, global change and runaway collapse in ecosystems. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 44, 503–538 (2013).

Tonelli, M., Fagherazzi, S. & Petti, M. Modeling wave impact on salt marsh boundaries. J. Geophys. Res. 115, C09028 (2010).

Andren, H. & Angelstam, P. Elevated predation rates as an edge effect in habitat islands: experimental evidence. Ecology 69, 544–547 (1988).

Laurance, W. F. & Yensen, E. Predicting the impacts of edge effects in fragmented habitats. Biol. Conserv. 55, 77–92 (1991).

Couvillion, B. R. et al. Land Area Change in Coastal Louisiana from 1932 to 2010: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Map 3164, scale 1:265,000, 12 p. Pamphlet http://pubs.usgs.gov/sim/3164/downloads/SIM3164_Pamphlet.pdf (2011).

Day, J. W. et al. Restoration of the Mississippi Delta: Lessons from Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Science 315, 1679–1684 (2007).

Kolker, A. S., Allison, M. A. & Hameed, S. An evaluation of subsidence rates and sea-level variability in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L21404 (2011).

Peyronnin, N. et al. Louisiana’s 2012 coastal master plan: overview of a science-based and publicly informed decision-making process. J. Coast. Res. 67, S1–S15 (2013).

Michel, J. et al. Extent and degree of shoreline oiling: Deepwater Horizon oil spill, Gulf of Mexico, USA. PLoS one 8, e65087 (2013).

McClenachan, G., Turner, R. E. & Tweel, A. W. Effects of oil on the rate and trajectory of Louisiana marsh shoreline erosion. Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 044030 (2013).

Zengel, S., Bernik, B. M., Rutherford, N., Nixon, Z. & J. Miche . Heavily oiled salt marsh following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, ecological comparisons of shoreline cleanup treatments and recovery. PLOS one 10, e0132324 (2015).

Hester, M. W. & Willis J. M. Sampling and Monitoring Plan for the Assessment of MC252 Oil Impacts to Coastal Wetland Vegetation in the Gulf of Mexico, August 4, 2011. Prepared for National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://www.gulfspillrestoration.noaa.gov/oil-spill/gulf-spill-data/(2011).

Hester, M. et al. Impacts of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill on the salt marsh vegetation of Louisiana. Env. Pollut. 216, 361–370 (2016).

Lin, Q., Mendelssohn, I. A., Graham, S. A., Hou, A., Fleeger, J. W. & Deis, D. R. Response of salt marshes to oiling from the Deepwater Horizon spill: Implications for plant growth, soil surface-erosion and shoreline stability. Sci. Total Environ. 557, 369–377 (2016).

Lin, Q., Mendelssohn, I. A., Suidan, M. T., Lee, K. & Venosa, A. D. The dose-response relationship between No. 2 fuel oil and the growth of the salt marsh grass, Spartina alterniflora. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 44, 897–902 (2002).

Lin, Q. & Mendelssohn, I. A. Impacts and recovery of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill on vegetation structure and function of coastal salt marshes in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 3737–3743 (2012).

Feagin, R. A., Lozada-Bernard, S. M., Ravens, T. M., Möller, I., Yeager, K. M. & Baird, A. H. Does vegetation prevent wave erosion of salt marsh edges? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 10109–10113 (2009).

Willis, J. M., Hester, M. W., Rouhani, S., Steinhoff, M. A. & Baker, M. C. Field assessment of the impacts of Deepwater Horizon oiling on coastal marsh vegetation of Mississippi and Alabama. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. doi: 10.1002/etc.3450.

Khanna, S. et al. Detection of salt marsh vegetation stress and recovery after the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill in Barataria Bay, Gulf of Mexico using AVIRIS data. PLoS one 8, e78989 (2013).

Silliman, B. R., Schrack, E., He, Q., Cope, R., Santoni, A., van der Heide, T., Jacobi, R., Jacobi, M. & von de Koppel, J. Facilitation shifts paradigms and can increase success of coastal restoration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 14295–14300 (2015).

Gedan, K. B., Kirwan, M., Barbier, E., Wolinksi, E. & Silliman, B. R. The present and future role of coastal wetland vegetation in protecting shorelines: answering recent challenges to the paradigm. Climatic Change 106, 7–29 (2011).

Temmerman, S. et al. Ecosystem-based coastal defense in the face of global change. Nature 504, 79–83 (2013).

Keddy, P. A. Quantifying within-lake gradients of wave energy: interrelationships of wave energy, substrate particle size and shoreline plants in Axe Lake, Ontario. Aquat. Bot. 14, 41–58 (1982).

Nixon, Z. Wave Exposure Indices and Deepwater Horizon Shoreline Oling. DWH NRDA Shoreline Technical Working Group Report. Prepared for National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration by RPI Available: https://pub-dwhdatadiver.orr.noaa.gov/dwh-ar-documents/901/DWH-AR0270321.pdf (2015).

Hollander, M., Wolfe, D. A. & Chicken, E. Nonparametric Statistical Methods, 3rd edition. Wiley, New York (2014).

Nelson, P. R., Wludyka, P. S. & Copeland, K. A. F. The Analysis of Means: A graphical method for comparing means, rates and proportions. SIAM, Philadelphia, PA (2005).

Bakir, S. T. Analysis of means using ranks for the randomized complete block design. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 23, 547–568 (1994).

Skillings, J. H. & Mack, G. A. On the use of a Friedman-type statistic in balanced and un-balanced block-designs. Technometrics 23, 171–177 (1981).

Culbertson, J. B., Valiela, I., Pickart, M., Peacock, E. E. & Reddy, C. M. Long-term consequences of residual petroleum on salt marsh grass. J. Appl. Ecol. 45, 1284–1292 (2008).

Li, Y., Morris, J. T. & Yoch, D. C. Chronic low level hydrocarbon amendments stimulate plant growth and microbial activity in salt-marsh microcosms. J. Appl. Ecol. 27, 159–171 (1990).

Michel, J. et al. Recovery of interior brackish marshes seven years after the chalk point oil spill. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 58, 995−1006 (2009).

Redondo-Gomez, S., Petenello, M. C. & Feldman, S. R. Growth, nutrient status and photosynthetic response to diesel-contaminated soil of a cordgrass, Spartina argentinensis. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 79, 34–38 (2014).

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. & Rothstein, H. R. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. Wiley, Chichester, UK (2009).

Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J. Stat. Softw. 36, 1–48 (2010).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria (2013).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge funding from the state of Louisiana, U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. National Science Foundation, The Stolarz Foundation and Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.R.S., P.M.D., C.W., Q.H., P.D., B.B.H., M.R., J.M.W. and M.W.H. contributed to writing, editing and data analysis. M.W.H. and J.M.W. were collaborators in the set-up and monitoring of the CWV survey and participated in collecting the data.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Silliman, B., Dixon, P., Wobus, C. et al. Thresholds in marsh resilience to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Sci Rep 6, 32520 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep32520

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep32520

This article is cited by

-

Fishery Closures, More Than Predator Release, Increased Persistence of Nearshore Fishes and Invertebrates to the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill

Estuaries and Coasts (2023)

-

Accelerated marsh erosion following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill confirmed, ameliorated by planting

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Massive Upland to Wetland Conversion Compensated for Historical Marsh Loss in Chesapeake Bay, USA

Estuaries and Coasts (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.