Abstract

It has been known for decades that certain aqueous salt solutions of LiCl and LiBr readily form glasses when cooled to below ≈160 K. This fact has recently been exploited to produce a « salty » high-pressure ice form: When the glass is compressed at low temperatures to pressures higher than 4 GPa and subsequently warmed, it crystallizes into ice VII with the ionic species trapped inside the ice lattice. Here we report the extreme limit of salt incorporation into ice VII, using high pressure neutron diffraction and molecular dynamics simulations. We show that high-pressure crystallisation of aqueous solutions of LiCl∙RH2O and LiBr∙RH2O with R = 5.6 leads to solids with strongly expanded volume, a destruction of the hydrogen-bond network with an isotropic distribution of water-dipole moments, as well as a crystal-to-amorphous transition on decompression. This highly unusual behaviour constitutes an interesting pathway from a glass to a crystal where translational periodicity is restored but the rotational degrees of freedom remaining completely random.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

All forms of ice are made of hydrogen-bonded networks of H2O molecules with local tetrahedral coordination, see refs 1, 2, 3, 4 and references therein. Such geometry is thought to be incompatible with the presence of ionic species since the electric field of an ion interacts strongly with the electric dipole moment of the water molecule and perturbs the directional H-bonding to its neighbours5. Indeed, when salt water freezes it tends to expel the salt, as observed in the shelf ice of freezing sea water6. A related effect is the ‘salting-out’ of proteins by concentrated salt solutions5. In general, the interaction of water with dissolved ionic species is of fundamental interest for various fields of research ranging from life sciences to planetology. High-pressure ice in contact with salt is a major ingredient in the geology of satellites in the outer solar system7,8 and the understanding of the interior of these bodies rely critically on our knowledge of properties of aqueous salt solutions under strong compression.

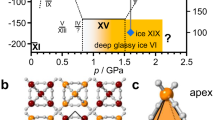

Recently, it has been shown that the most stable high-pressure ice phase, ice VII, can accommodate significant amounts of Li+ and Cl− ions, if prepared by pressure-induced crystallisation of the glassy solution9. In fact, in a narrow concentration range between R = 5.5 and R = 6.5, aqueous LiCl and LiBr solutions LiCl∙RH2O and LiBr∙RH2O easily form glasses, simply by cooling the liquid, see Fig. 1 10,11. When such a solid solution with R = 6 is compressed below 100 K and heated, it crystallises into ‘salty ice VII’ where the Li-ions are trapped interstitially in the octahedral voids of the bcc-type ice VII structure, and the Cl− ion are located at water sites9. Such ‘doping’ of ice VII leads to an increased unit cell volume and a local perturbation of the hydrogen bond network which is visible in the diffraction patterns by an increased Debye-Waller factor. The very narrow range wherein such solid amorphous aqueous solutions can be prepared (Fig. 1) suggests that the crystallisation behaviour into ice VII depends sensitively on the salt concentration. In the following we show that this is indeed the case, i.e. that the structure of such crystallized salty ice VII is highly sensitive to the amount of salt inclusions, and that they give rise to salty ices with strongly expanded volumes, random water-dipole orientation and crystal-amorphous transitions under decompression at low temperatures.

10 ,11 . In a small region of concentration R ≈ 5.5–6, the supercooled liquid transforms directly into a glass. Regions to the left and the right are stability domains of ice and various hydrates. Right panel: Pressure-temperature path applied to form LiCl- and LiBr containing ice VII together with the phase diagram of pure water. Red dots indicate initial sample conditions at ambient pressure.

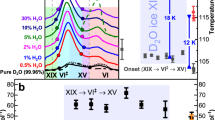

For this purpose, deuterated aqueous solutions with R = 5.6 of LiCl and LiBr (LiCl∙5.6D2O, and LiBr∙5.6D2O) were prepared. They present the limit of salt concentration where a homogeneous glass can easily form without applying extreme cooling speeds. We used deuterated samples to avoid the very large incoherent scattering of hydrogen, a standard method applied in powder neutron diffraction, including in almost all previous structural work on ice2,3,4,9 (the isotope effect on the structure and phase diagram of ice is known to be negligible). The vitrified samples were then compressed at 80–85 K to pressures between 4 and 6 GPa and warmed to 300 K while keeping the pressure approximately constant. Neutron diffraction patterns were collected during the warm-up with accumulation times between 5 and 20 minutes. Figure 2 shows the behaviour of both the LiCl- and the LiBr-samples close to room temperature. Crystallisation of the glass is observed to start at ≈270 K and reaches a stable state slightly above 300 K. The diffraction patterns are characterized by a single, large peak at d ≈ 2.5 Å corresponding to the 110 Bragg reflection of ice VII. All other (sharp) reflections are either from a small amount of lead which was added as a pressure marker, or tungsten carbide which is the anvil material. Obviously, the high-pressure crystallized solids are far from being perfect crystals, but they certainly cannot be qualified as a glass either. In fact, the patterns are sufficiently crystalline to be able to analyze them by Rietveld methods, as shown in Fig. 3 for the two systems. Without surprise the fits are not perfect since they cannot reproduce the significant diffuse scattering which leads to the asymmetric wings around the 110 reflection. The large width of the reflection is most likely a particle size effect (typical size: 20 Å), and to a minor extent due to strain, as deduced from the refined peak shape parameters.

Sharp peaks are from lead, the asterisk is a reflection from the tungsten carbide anvils. Expected positions of 111 and 211 reflections are indicated by red and blue arrows, respectively. Upper and lower tick marks correspond to reflections of ice VII and lead, respectively, the difference curves are shown below. Accumulation time is 15 (left) and 30 minutes (right). For comparison, a pattern of well-crystallised pure ice VII at 4.7 GPa is shown in the inset including Miller indices of the three strongest reflections. Crosses indicate reflections of the lead pressure marker.

The most surprising feature of these patterns is, however, the total absence of the 111 reflection which should occur at ≈2.0 Å (red arrows in Fig. 3), and which is clearly present in samples with lower salt concentrations9. This cannot be an effect of the strong Debye-Waller factor since the 211 reflection at lower d-spacing (≈1.35 Å, blue arrows in Fig. 3) is clearly visible, though weak, as expected. In the ice VII structure, the 111 reflection is entirely due to hydrogen (deuterium), i.e. it has no contribution from oxygen. Therefore, its absence is a clear and unambiguous proof of hydrogen being strongly displaced from its normal position along <x,x,x>, see Fig. 5 for a sketch of the ice VII structure and inset of Fig. 3 for a comparison with a pattern of pure ice VII. In initial fits this effect was simulated by varying displacement factors for hydrogen which gave <x2>1/2 ≈ 0.6 Å, which is indeed large. For comparison, the displacements in pure ice VII at 2.6 GPa and 295 K are <x2>1/2 ≈ 0.15–0.20 Å12,13, i.e. more than three times smaller. A more realistic model with 8 positions was hence adopted, 4 positions along <x,x,x>, and 4 others at the anti-tetrahedral (‘interstitial’) positions, a geometry which describes a more isotropic distribution of H around O. Refinements in this model gave better fits with reduced H-displacements of <x2>1/2 ≈ 0.30 Å. Fits based on this model correspond to the lines through the data shown in Fig. 3, and results of the refinements are given in Table 1. In conclusion, whatever the detail of the model adopted, the evidence is that hydrogen is more or less isotropically disordered. This necessarily entails – given the fact that the molecular geometry is intact - that the electric dipole moment has no preferred orientation with respect to the crystallographic axes.

The distribution was normalized to give an integrated probability equal to one. Note a very weak preference of dipoles along <100> in the LiCl-system, and a completely flat distribution for the LiBr-system. A sketch of a typical instantaneous configuration in pure ice VII is given (lower left) with hydrogen bonds indicated as dashed lines and the non-bonding (“anti-tetrahedral”) directions as dotted lines.

The second remarkable feature is the strongly expanded lattice parameter: at the pressures measured by the lead marker the volume expansion relative to pure ice VII is 14% and 18% for the LiCl- and LiBr-system, respectively. These values scale exactly with the difference in size r of the anions involved, i.e. rCl = 1.81 Å and rBr = 1.96 Å, i.e. it is an unambiguous proof that the ions are indeed included into the structure, on specific lattice sites. Surprisingly, the volume expansion is not proportional to the salt content: For a 7% lower LiCl concentration (R = 6), the volume expansion was observed to be 43% smaller (i.e. only 8%)9. This sensitivity to the salt concentration must be related to the fact that – contrary to the low pressure ice forms - phase VII achieves its high density through interpenetration, i.e. by forming two interpenetrating but non-connected sublattices. Such a configuration permits, for example, to have the shortest O-O distances larger than in ordinary ice Ih, despite its considerably larger density. The destruction of the interpenetrating sublattices by the presence of ionic species must necessarily lead to an increase of volume which is expected to be highly sensitive to the ion concentration.

The structural properties of these highly salt-loaded ice phases were then investigated by molecular dynamics simulations which give access to physical properties which cannot be extracted by diffraction measurements alone. For this purpose simulations were carried out with 15 × 15 × 15 ice VII supercells corresponding to 19227 atoms. Note that the structural results are insensitive to the choice of the isotope (hydrogen or deuterium) since the potentials used in the simulations are the same. Details of the calculations are described in the Methods section.

Figure 4 shows a snapshot of typical molecular configurations in LiCl∙5.6H2O compared to pure ice VII, viewed along the cubic [100] direction. Results for the LiBr-system are qualitatively similar and are not shown here. It is seen that inclusion of Li+ and Cl− leads to molecular displacements of several tenths of angstroms, but on average the H2O molecules are still at the bcc sites of ice VII. It is also seen that the Li+-ions prefer to locate themselves in the octahedral interstitials, whereas the much larger Cl-ions are on average closer to sites where H2O is expected. Radial distribution functions were calculated for the two systems and can be found as Supplementary Information. These indicate an average of three H-atoms up to a distance of 2.1 Å compared to four in pure ice VII, suggesting that a sizeable number of H-bonds are broken.

The most important detail in this context concerns however the spatial distribution of dipole moments. For this purpose the orientation of each water molecule was extracted from the last part of the 12 ns trajectory (1 ns) and employed to build the spherical probability maps shown in Fig. 5. The probability density is normalized so as to give an integral over all orientations equal to one. For comparison, a similar-size model of ice VII was also built and equilibrated at constant pressure P = 10 GPa and T = 300 K (see Methods for the choice of the pressure).

As shown in the Fig. 5, pure ice VII is characterized by molecular dipoles sharply aligned along [100] and equivalent directions, as expected. In LiCl∙5.6H2O and LiBr∙5.6H2O, however, the orientational probability is almost exactly isotropic. Close inspection of the dipole distribution shows a small residual preference for <100> directions in the case of LiCl∙5.6H2O which is hardly discernible in Fig. 5, but an almost isotropic distribution for the Br-system. This is confirmed by calculating the standard deviation σ of the probability over all dipole orientations. For the Cl-system we find σ(LiCl) = 0.012, for the Br-system σ(LiBr) = 0.0090, with average probabilities of 0.075 (LiCl) and 0.078 (LiBr), i.e. relative variations of only 16% and 11%, respectively.

The simulations therefore come to the same conclusion as the diffraction data: The ice VII-like structures emerging from crystallisation of highly concentrated LiCl and LiBr-solutions under pressure have completely disordered molecular orientations which means that a large fraction of hydrogen-bonds are broken and that the ice-rules are violated. This distinguishes it sharply from the orientational disorder present in most of the (pure) ice phases where the ice-rules are conserved. The crystallisation observed here could be classified as ‘fractional’ since it concerns mainly the three translational degrees of freedoms whereas the three rotational freedoms remain uniformly random. Breaking of hydrogen bond networks is a phenomenon which has been observed in liquid salt solutions at ambient pressure10,14, and also in pure liquid water above the critical point15. For solid water, however, including amorphous ice phases, this seems to be a new observation which is only possible by crystallisation of the solutions under pressure.

In this context the question arises if the inclusion of ionic species into ice VII promotes “plasticity”, i.e. the formation of an ice VII phase with freely rotating molecules, as predicted by several simulations16,17,18 to occur close to the melting line. A diffraction experiment can – by principle – not give information on the dynamics of molecular orientations, but our simulations can safely exclude this scenario. In fact, the calculated orientational correlation times of water dipoles in LiCl∙5.6H2O and LiBr∙5.6H2O are typically 4–5 times longer compared to pure ice VII at the same pressure. Therefore, although the ions severely perturb the H-bond network, their presence seems to hamper their orientational dynamics rather than to promote it.

A further interesting aspect concerns the behaviour under de-compression at low temperatures: The two salty ice-forms are found to be not quenchable at 90 K, and probably even not at any temperature below, contrary to all forms of pure ice. Figure 6 shows diffraction patterns of the two systems at ambient pressure and the same temperature, before compression and after the compression/crystallisation cycle, after decompression at ≈90 K. The surprising finding is that both ice VII forms of LiCl∙5.6D2O and LiBr∙5.6D2O return to an amorphous solid, a disordered system which is significantly different from the original glass. A comparison with published structure factors from ref. 19 shows a striking resemblance with high density amorphous ice (HDA), except that the main diffraction feature is at ≈0.2 Å shorter d-spacing, approximately at a position where it is found in very high density amorphous ice (VHDA)20. From this we suspect that upon decompression, the hydrogen-bond network might be partially restored with a slightly higher molecular density than found in HDA. Hence, we observe a strong memory effect: the vitrified glass has a memory of the liquid with its structure governed by hydration of the ionic species, whereas the de-compressed amorphous ice has kept a memory of the crystalline ice VII, where the cohesion is governed by the need for maximizing the packing density.

In conclusion, we have presented neutron diffraction and molecular simulation results on highly concentrated LiCl- and LiBr aqueous solutions which were crystallized under high pressure. They indicate that the ionic species can be trapped inside a strongly expanded ice VII – like structure with random electric dipole orientation. These structures cannot be quenched (‘recovered’) to ambient pressure and low temperatures but transform back to a glass with a structure different to the initial one. The trapping of ionic species by crystallisation from a glass (devitrification) might be found in other network forming glasses, for example in silica. In fact, “stuffed” SiO2 polymorphs incorporating small ions such as lithium are well known and can be formed at ambient pressure21. The high-pressure route used in this study might enable to synthesize “stuffed” high pressure silica phases which are expected to have remarkable properties, for example improved hardness, and therefore might be of technological interest.

Methods

Sample preparation

Aqueous solutions of LiCl and LiBr with R = 5.6 were prepared from the salts purchased from Aldrich, and 99.8% enriched heavy water (D2O) from Eurisotop, France. The solutions were filtered to remove particles larger than 3 μm to minimize the possibility of crystallisation during cooling, and loaded into TiZr gaskets together with a small piece of lead (10 mg). After sealing the gasket with a load of 10 kN onto the anvils the cell was cooled at a speed of 10 K/min to 80 K which transformed the liquids into pure glasses. The samples were then compressed at 80–110 K in steps up to 4–5 GPa and then heated at an average speed of typically 1 K/min up to the temperature where crystallisation occurred. After crystallisation, the samples were stable over at least the timescale of the diffraction experiments, i.e. 1–3 hours. Samples at lower pressures (below ca. 3.3 GPa for the LiCl compound and ca. 4.3 GPa for the LiBr system) crystallized into solids with unknown structure.

Neutron diffraction

High pressure neutron diffraction measurements were carried out at the Japanese high pressure beamline PLANET22 at MLF, the Japan Accelerator Research Complex (J-PARC), Tokai, Ibaraki, Japan, using a variable P-T hydraulic press (‘Mito system’)23, and tungsten carbide anvils with a profile as described in ref. 24 and 9/6 mm outer/inner diameters. Encapsulating gaskets were made of null-scattering TiZr, surrounded by a supporting ring of a high-tensile aluminium alloy24. Normalisation of the data was achieved in a separate run using a vanadium pellet and an anvil configuration which was strictly similar.

Molecular dynamics simulations

Salty ices of stoichiometry Li(Cl/Br)∙5.6H2O have been simulated employing the TIP4P/Ew interatomic potential for water25 and the potentials of Joung & Cheatham for Li+, Cl−, and Br− ions26. The potentials for hydrogen and deuterium are strictly identical which allows us to make meaningful comparison with the neutron diffraction data which used deuterated samples. Molecular dynamics simulations were performed employing the software Gromacs27. The temperature was controlled with the stochastic velocity rescaling thermostat28, and the pressure with a Berendsen barostat29. For each composition (Cl or Br) samples were generated in the following way: Ice VII 15 × 15 × 15 supercells with 19227 atoms were constructed employing the experimental lattice parameter (a = 3.42835 Å with Cl and a = 3.45795 Å with Br) and positioning 6750 water molecules at ideal bcc lattice sites with a random orientation of dipoles, imposing the ice rules. 1023 water molecules, selected at random, were removed and replaced with either Cl− or Br− ions. Finally, 1023 Li+ ions were introduced choosing randomly their positions among the centers of octahedra defined by water molecules and halide ions. These initial geometries were constructed avoiding to place two identical ions closer than the lattice parameter a. The composition corresponds to a stoichiometry Li(Cl/Br)∙5.63H2O. Each structure was initially relaxed at T = 10 K and constant volume for 30 ps (with a timestep of 0.1 fs). Then, the system was slowly heated up to T = 300 K employing a time constant of 50 ps for the thermostat (with a timestep of 1 fs) and equilibrated for 12 ns. The dipole moment orientation of each water molecule was extracted from the last part of the trajectory (1 ns) and employed to build the spherical probability maps. The orientational correlation time of water dipoles was estimated performing, for each system, additional 50 ns-long simulations using deuterium instead of hydrogen masses. In a second set of simulations a smaller 4 × 5 × 7 cell was used to generate 100 configurations which served to calculate neutron diffraction patterns and verify the consistency with experiment. Note that constraining the system at the experimental volume corresponds to a pressure of about 10 GPa: this is consistent with the domain of stability of ice VII with the interatomic potential employed30, whereas imposing the experimental pressure (4–5 GPa) to the theoretical samples would correspond to the stability domain of the liquid resulting in much more disordered structures.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Klotz, S. et al. Ice VII from aqueous salt solutions: From a glass to a crystal with broken H-bonds. Sci. Rep. 6, 32040; doi: 10.1038/srep32040 (2016).

References

Petrenko, V. F. & Whitworth, R. W. Physics of Ice, Oxford University Press (Oxford, 2002).

Bartels-Rausch, Th. et al. Ice structures, patterns and processes: A view across the icefield. Review of Modern Physics 84, 885–944 (2012).

Salzmann, Ch. G., Radaelli, P. G., Hallbrucker, A., Mayer, E. & Finney, J. L. The preparation and structures of hydrogen ordered phases of ice. Science 311, 1758–1761 (2006).

Falenty, A., Hansen, Th. C. & Kuhs, W. F. Formation and properties of ice XVI obtained by emptying a type sII clathrate hydrate. Nature 516, 231–233 (2014).

Marcus, Y. Effect of ions on the structure of water: Structure making and breaking. Chem. Rev. 109, 1346–1370 (2009).

Lake, R. A. & Lewis, E. L. Salt rejection by sea ice during growth. Journal of Geophys. Research 75, 583–597 (1970).

Frank, M. R., Runge, C. E., Scott, H. P., Maglio, S. J., Olson, J., Prakapenka, V. B. & Shen, G. Experimental study of the NaCl-H2O system up to 28 GPa: Implications for the ice-rich planetary bodies. Phys. Earth Planet. Interiors 155, 152–162 (2008).

Journaux, B., Daniel, I., Caracas, R., Montagnac, G. & Cardon, H. Influcence of NaCl on ice VI and ice VII melting curves up to 6 GPa, implications for large icy moons. Icarus 226, 355–363 (2013).

Klotz, S., Bove, L. E. B., Strässle, Th., Hansen, Th. C. & Saitta, A. M. The preparation and structure of salty ice VII under pressure. Nature Materials 8, 405–409 (2009).

Prével, B., Jal, J. F., Dupuy-Philon, J. & Soper, A. K. Structural characterization of an electrolytic aqueous solution, LiCl∙6H2O, in the glass, supercooled, and liquid states. The Journal of Chemical Physics 103, 1886–1896 (1995).

Kessis, J. J. Le système eau-bromure de lithium. Bulletin de la société chimique de France, 48–52 (1965).

Kuhs, W. F., Finney, J. L., Vettier, C. & Bliss, D. V. Structure and hydrogen ordering in ices VI, VII, and VIII by neutron powder diffraction. The Journal of Chemical Physics 81, 3612–3623 (1984).

Jorgensen, J. D. & Worlton, T. G. Disordered structure of D2O ice VII from in situ neutron powder diffraction. The Journal of Chemical Physics 83, 329–333 (1985).

Tromp, R. H. H., Neilson, G. W. & Soper, A. K. Water structure on concentrated lithium chloride solutions. The Journal of Chemical Physics 96, 8460–8469 (1992).

Postorino, P., Tromp, R. H., Ricci, M. A., Soper, A. K. & Neilson, G. W. The interatomic structure of water at supercritical temperatures. Nature 366, 668–670 (1993).

Takii, Y., Koga, K. & Tanaka, H. A plastic phase of water from computer simulation. The Journal of Chemical Physics 128, 204501–8 (2008).

Aragones, J. L. & Vega, C. Plastic crystal phases of simple water models. The Journal of Chemical Physics 130, 244504–14 (2009).

Matsumoto, M., Himoto, K. & Tanaka, H. Spin-one Ising model for ice VII-plastic ice phase transformations. Journal of Physical Chemistry B 118, 13387–13392 (2014).

Bellissent-Funel, M. C., Teixeira, J. & Bosio, L. Structure of high-density amorphous water. II. Neutron scattering study. The Journal of Chemical Physics 87, 2231–2235 (1987).

Bowron, D. T., Finney, J. L., Hallbrucker, A., Kohl, I., Loerting, T. Mayer, E. & Soper, A. K. The local and intermediate range structures of the five amorphous ices at 80 K and ambient pressure: A Faber-Ziman and Bhatia-Thornton analysis. The Journal of Chemical Physics 125, 194502–14 (2006).

Palmer, D. C. Stuffed derivatives of the silica polymorphs. In: Silica – Physical behavior, geochemistry and materials applications (editors Herney, P. J., Prewitt, C. T. & Gibbs, G. V. ) 83–122, Review in Mineralogy, vol. 29 (Mineral Soc. of America, Washington D.C., 1994).

Hattori, T. et al. Design and performance of high-pressure PLANET beamline at pulsed neutron source at J-PARC. Nucl. Instrum. Methods in Phys. Res. A 780, 55–67 (2015).

Komatsu, K., Moriyama, M., Koizumi, T., Nakayama, K., Kagi, H., Abe, J. & Hario, S. Development of a new P-T controlling system for neutron-scattering experiments, High Pressure Res. 33, 208–213 (2013).

Komatsu, K., Klotz, S., Shinozaki, A., Iizuka, R., Bove, L. E. & Kagi, H. Performance of ceramic anvils for high pressure neutron scattering, High Pressure Res. 34, 494–499 (2014).

Horn, H. W., Swope, W. C., Pitera, J. W., Madura, J. D., Dick, T. J., Hura, G. L. & Head-Gordon, T. Development of an improved four-site water model for biomolecular simulations: TIP4P-Ew. The Journal of Chemical Physics 120, 9665–9678 (2004).

Joung, I. S. & Cheatham III, T. E. Determination of alkali and halide monovalent ion parameters for use in explicitly solvated biomolecular simulations. The Journal of Phys. Chem. B 112, 9020–9041 (2008).

Hess, B., Kutzner, C., Van Der Spoel, D. & Lindahl, E. GROMACS 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 4, 435–447 (2008).

Bussi, G., Donadio, D. & Parrinello, M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. The Journal of Chemical Physics 126, 014101 (2007)

Berendsen, H. J. C., Postma, J. P. M., van Gunsteren, W. F., DiNola, A. & Haak, J. R. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. The Journal of Chemical Physics 81, 3684–3690 (1984).

Vega, C., Abascal, J. L. F., Sanz, E., MacDowell, L. G. & McBride, C. Can simple models describe the phase diagram of water? Journal of Physics: Condens . Matter 17, S3283–S3288 (2005).

Strässle, Th ., Klotz, S., Kunc, K., Pomjakushin, V. & White, J. S. Equation of state of lead from high-pressure neutron diffraction up to 8.9 GPa and its implication for the NaCl pressure scale. Phys. Rev. B 90, 014101–8 (2014).

Besson, J. M., Pruzan, Ph., Klotz, S., Hamel, G., Silvi, B., Nelmes, R. J., Loveday, J., Wilson, R. M. & Hull, S. Variation of interatomic distances in ice VIII to 10 GPa. Phys. Rev. B 49, 12540–12551 (1994).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the French-Japanese PHC grant 29717X between IMPMC and the University of Tokyo (P.I.: S.K. and H.K.), the JSPS KAKENHI grant no. 26246039, the cluster of excellence MATériaux Interfaces Surfaces Environnement (MATISSE) led by Sorbonne Universités, through a PhD fellowship for A.-A.L. and by the ANR within the Blanc International program PACS under reference no. ANR-13-IS04-0006-01. The experiment at the Materials and Life Science Experimental Facility of the J-PARC was performed under a user program (Proposal No. 2014A0048). The authors wish to thank Dr. J. Abe for much assistance during the experiments at the PLANET beamline and D. Bowron, L. Cormier, Ch. Sanloup and H. Fischer for helpful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.K. and L.E.B. proposed the experiment, S.K., A.-A. L., K.K., H.K., S.M., T.H. and A.S.-F. carried out the experiments. S.K. did the neutron data analysis and wrote the paper. F.P. did the molecular dynamics simulations.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Klotz, S., Komatsu, K., Pietrucci, F. et al. Ice VII from aqueous salt solutions: From a glass to a crystal with broken H-bonds. Sci Rep 6, 32040 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep32040

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep32040

This article is cited by

-

Stability of high-temperature salty ice suggests electrolyte permeability in water-rich exoplanet icy mantles

Nature Communications (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.