Abstract

We develop a formalism, based on the mode expansion method, to describe the guided resonances and bound states in the continuum (BICs) in photonic crystal slabs with one-dimensional periodicity. This approach provides analytic insights to the formation mechanisms of these states: the guided resonances arise from the transverse Fabry–Pérot condition and the divergence of the resonance lifetimes at the BICs is explained by a destructive interference of radiation from different propagating components inside the slab. We show BICs at the center and on the edge of the Brillouin zone protected by symmetry, BICs at generic wave vectors not protected by symmetry and the annihilation of BICs at low-symmetry wave vectors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Conventionally, the confinement of waves is achieved by spectrally separating the bound state away from the continuum of radiating waves that can carry energy away—examples include electronic bound states at negative energies and light guided below the light line or inside a photonic bandgap. Bound states in the continuum (BICs) are special states that remain localized and have infinite lifetimes even though they reside inside the continuum1. Historically, BIC was first proposed by von Neumann and Wigner for an electron in an engineered potential2, although such an electron BIC has never been achieved. More recently, optical BICs have been experimentally realized in a range of photonic systems3,4,5,6,7,8,9. In periodic structures, BICs may be found by varying the incident angle without tuning the structure, which makes their realization relatively simple3,5,6,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22 (Note: Originally, BICs are proposed as localized states integrable in all the three dimensions2. But in periodic structure, BICs are extended in periodical directions while spatially confined in other directions). Photonic crystal (PhC) slabs—dielectric slabs with periodically modulated refractive index10,17,23,24—are particularly attractive given their macroscopic sizes and ease of fabrication. The guided resonances and BICs in PhC slabs have been used for a wide range of applications such as lasers25,26,27,28,29, sensors12,30,31 and filters32. When BICs do exist, their robustness can be explained by the zero-crossing of radiating amplitudes6 or, more generally, by their topological charges18. However, this does not reveal the physical mechanism that suppresses radiation and leads to the localization. In the presence of multiple resonances, the disappearance of radiation can be explained by the destructive interference of the radiating waves from different resonances7,12,13,14,15,33,34. When only one resonance is present, an explanation based on destructive interference should still be possible, but it is no longer clear which sets of waves are interfering. Furthermore, the theoretical studies of BICs have largely relied on numerical simulations that are time consuming and provide little insight.

Here, we develop a mode expansion method that explains the formation mechanism of guided resonances and BICs in PhC slabs. In this formalism, guided resonances require the round-trip transverse phase shift for each in-slab propagating mode to be an integer multiple of 2π and BICs arise from the destructive interference of radiation from different propagating waves inside the slab. This method is also capable of calculating the resonance frequency, quality factor and field profile efficiently with no approximation other than a truncation of the basis size and we validate these results with finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) simulations. For PhC slabs in a periodic inhomogeneous backgrounds, we find symmetry-protected BICs both at the center and on the edge of the Brillouin zone, in addition to those inside the Brillouin zone where they are not protected by symmetry. Although we only show examples for systems with one dimensional periodicity, our mode expansion method can be extended to systems that are periodic in two dimensions.

Methods

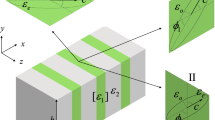

For simplicity, we consider TM modes (Hx, Hy, Ez) in a PhC slab that is periodic in y and uniform in z (Fig. 1a); the generalization to TE modes (Ex, Ey, Hz) and to PhC slabs with two-dimensional periodicity is straightforward. We consider structures that are mirror-symmetric in the normal direction x (this symmetry is necessary for reducing the number of radiation channels6) and where the slab permittivity ε1(y) is uniform in x (common in most fabricated structures of PhC slabs). Here we consider two cases: the permittivity of the surrounding medium ε2(y) is a constant (Fig. 1b) or is periodic with the same period a as the slab (Fig. 1c). Inside (|x| < 0.5h) and outside (|x| > 0.5h) the slab, the structure is uniform in x, so the fields can be expanded in the eigenmodes of ε1(y) and ε2(y) with a sinusoidal dependence along x; the expansion coefficients can be determined by continuity at the slab surface |x| = 0.5h. Specifically, with an outgoing boundary condition in x, an even-in-x TM mode with wave vector ky can be written as35

(a) Structure: a 1D-periodic photonic crystal (PhC) slab with permittivity ε1(y) surrounded by a dielectric media with permittivity ε2(y). ε1 and ε2 have the same period of a, ε1(y + a) = ε1(y), ε2(y + a) = ε2(y). (b) Schematic of a 1D PhC slab embedded in homogeneous dielectric medium. (c) Schematic of a 1D PhC slab embedded in a periodic dielectric background.

where h is the slab thickness, the cosine inside the slab guarantees the even-in-x symmetry and the complex exponential outside the slab guarantees the outgoing boundary condition. TM modes satisfy the wave equation  where k0 = ω/c, ω is the frequency and c is the vacuum speed of light; inserting Eq. (1) into this wave equation, we find that the eigenfunctions and propagation constants um(y), ϑm(y), βmand γm inside and outside the slab satisfy

where k0 = ω/c, ω is the frequency and c is the vacuum speed of light; inserting Eq. (1) into this wave equation, we find that the eigenfunctions and propagation constants um(y), ϑm(y), βmand γm inside and outside the slab satisfy

where  for l = 1, 2 are the Hermitian operators governing the wave equation for the layers inside and outside the slab, subject to periodic boundary condition um(y + a) = um(y), ϑm(y + a) = ϑm(y). For a given frequency and ky, there will be a finite number of eigenmodes with

for l = 1, 2 are the Hermitian operators governing the wave equation for the layers inside and outside the slab, subject to periodic boundary condition um(y + a) = um(y), ϑm(y + a) = ϑm(y). For a given frequency and ky, there will be a finite number of eigenmodes with  (or

(or  ) that propagate in the x direction, with an infinite number of eigenmodes with

) that propagate in the x direction, with an infinite number of eigenmodes with  (or

(or  ) that are evanescent in x. Similar expansion methods were used previously for water waves21 and for quantum waveguides36. Odd-in-x TM modes can be written similarly by replacing the cosine in Eq. (1) with sine and TE modes can be treated by replacing

) that are evanescent in x. Similar expansion methods were used previously for water waves21 and for quantum waveguides36. Odd-in-x TM modes can be written similarly by replacing the cosine in Eq. (1) with sine and TE modes can be treated by replacing  with that for Hz. Cm and Tm are coefficients of the eigenmode expansion and they can be determined via the continuity of Ez and ∂Ez/∂x at x = 0.5h, which requires

with that for Hz. Cm and Tm are coefficients of the eigenmode expansion and they can be determined via the continuity of Ez and ∂Ez/∂x at x = 0.5h, which requires

The standing waves inside the slab [the cos (βmx) in Eq. (1)] are superposition of waves propagating in +x and in –x directions, so one can interpret the in-slab fields as waves circulating within the slab with reflection and transmission at the two slab surfaces. The transverse phase shift for every propagating component is an integer multiple of 2π after a round trip with two reflections, which is the same resonance condition as the Fabry–Pérot resonances in uniform dielectric slabs; the difference is that here multiple propagating components are coupled due to the periodicity in y.

While the two sets of eigenmodes {ϑm} and {um} each form an infinite-dimensional basis, the high-order ones correspond to fast oscillating fields that are negligible at low frequencies. Therefore, in our calculations, we truncate down to M terms by expanding the eigenmodes in an M-dimensional basis (details below). In the truncated basis, the transformation between the two bases {ϑm} and {um} is given by to an M × M matrix P such that  . In this way, the continuity condition Eqs (4, 5) can be written in matrix form as

. In this way, the continuity condition Eqs (4, 5) can be written in matrix form as

where T = [T1, …, TM−1, TM]T, C = [C1, …, CM−1, CM]T and γ, B are diagonal matrices γ = Diag(γ1, …, γM), B = Diag (β1 tan (0.5β1h), …, βM tan (0.5βMh)). Note that the matrix B is purely real since  is real for all m. Eq. (4) is a linear equation group for vectors T and C. Substituting Eq. (6) into Eq. (7) yields (iγP + PB)C = 0. Non-trivial solutions exist when

is real for all m. Eq. (4) is a linear equation group for vectors T and C. Substituting Eq. (6) into Eq. (7) yields (iγP + PB)C = 0. Non-trivial solutions exist when

where ||*|| denotes the determinant of the matrix. Therefore, solving for Eq. (8) for a given ky yields the dispersion relation ω (ky) for arbitrary resonances and BICs, as well as regular bound states. The vector C corresponding to the zero determinant and the associated vector T from Eq. (6) yield the field profile as given in Eq. (1). At frequencies in the continuum spectrum of the surrounding medium ( for a homogeneous medium), some of the γm’s are real and f (ky, ω) is generally complex-valued; in such region finding the zeroes of f (ky, ω) requires searching for solutions on the lower half of the complex-frequency plane with ωr = Re(ω) and ωi = Im(ω) being the parameters. The imaginary part of the frequency is the decay rate and the quality factor of the resonance is Q = −ωr/(2ωi).

for a homogeneous medium), some of the γm’s are real and f (ky, ω) is generally complex-valued; in such region finding the zeroes of f (ky, ω) requires searching for solutions on the lower half of the complex-frequency plane with ωr = Re(ω) and ωi = Im(ω) being the parameters. The imaginary part of the frequency is the decay rate and the quality factor of the resonance is Q = −ωr/(2ωi).

The transformation matrix P is deduced from Eqs (2, 3). Inspired by ref. 24, we expand both sides of Eqs (2, 3) in Fourier series and truncate to Fourier orders from –N to N (with a total of M = 2N + 1 terms). Then, Eqs (2, 3) can be written as matrix equations

with β = Diag(β1, …, βM) and Hl is an M × M matrix whose (m, m′)-th element is  , where n = m − N − 1, n′ = m′ − N − 1 and ξl (n) is the n-th Fourier coefficient of εl (y). The m-th column of Φ (or Θ) contains the –N-to-N Fourier coefficients of um (or ϑm). Φ and Θ are transform matrices connecting {um} and {ϑm} to the same basis with plane-wave elements, hence P = Θ−1Φ. Note that when the permittivity is real and mirror symmetric in y,

, where n = m − N − 1, n′ = m′ − N − 1 and ξl (n) is the n-th Fourier coefficient of εl (y). The m-th column of Φ (or Θ) contains the –N-to-N Fourier coefficients of um (or ϑm). Φ and Θ are transform matrices connecting {um} and {ϑm} to the same basis with plane-wave elements, hence P = Θ−1Φ. Note that when the permittivity is real and mirror symmetric in y,  , the matrices Hl are real symmetric, so β2 and γ2 are real; moreover, Φ, Θ and P can be chosen to be purely real.

, the matrices Hl are real symmetric, so β2 and γ2 are real; moreover, Φ, Θ and P can be chosen to be purely real.

BICs arise when the decay rate γ = −2ωi of a resonance becomes zero, or equivalently when the amplitudes of the radiating waves vanish: Tm′ = 0 for all the m′ with  . From Eq. (6), Tm′ is given by

. From Eq. (6), Tm′ is given by

where  is the (m′,m)’s element of matrix P, which is the m′-th component of the in-slab eigenmode um in the basis of {ϑm′}. Equation (11) reveals that the radiating wave of port m′ comes from interference of all the contributions from {um} to the radiating mode ϑm′. Therefore, Tm′ = 0 is a result of destructive interference from the in-slab eigenmodes to the radiation modes.

is the (m′,m)’s element of matrix P, which is the m′-th component of the in-slab eigenmode um in the basis of {ϑm′}. Equation (11) reveals that the radiating wave of port m′ comes from interference of all the contributions from {um} to the radiating mode ϑm′. Therefore, Tm′ = 0 is a result of destructive interference from the in-slab eigenmodes to the radiation modes.

Numerically it can be ambiguous to determine whether ωi is very small or identically zero. Therefore, we use a slightly modified scheme to look for exact BICs. Define f ′ as  : the propagation constants of the radiating waves γm′ are artificially set to zero; this function f ′ is purely real for a lossless dielectric structure that is symmetric in y (where Hl is real symmetric). A BIC not only satisfies f = 0; it also satisfies f ′ = 0 since Tm′ = 0 for a BIC and from Eq. (5) it can be seen that setting γm′ to zero does not change the solution. Therefore, to search for BICs, we first solve the real-valued equation f ′(ky, ω) = 0 at each ky for a real-valued frequency ω; the solution also provides a mode profile given by T and C. However, such a mode profile will only satisfy the continuity condition, Eqs (4 and 5), if Tm′ = 0. In this work, we study the frequency range where there is only one leaky channel (only one m′ with

: the propagation constants of the radiating waves γm′ are artificially set to zero; this function f ′ is purely real for a lossless dielectric structure that is symmetric in y (where Hl is real symmetric). A BIC not only satisfies f = 0; it also satisfies f ′ = 0 since Tm′ = 0 for a BIC and from Eq. (5) it can be seen that setting γm′ to zero does not change the solution. Therefore, to search for BICs, we first solve the real-valued equation f ′(ky, ω) = 0 at each ky for a real-valued frequency ω; the solution also provides a mode profile given by T and C. However, such a mode profile will only satisfy the continuity condition, Eqs (4 and 5), if Tm′ = 0. In this work, we study the frequency range where there is only one leaky channel (only one m′ with  ) and we perform a root finding with ky being the free parameter to look for solutions of f ′ = 0 where the amplitude of this radiation channel vanishes, Tm′ = 0. Once found, such a solution will be a true bound state at a purely real frequency and with no radiation.

) and we perform a root finding with ky being the free parameter to look for solutions of f ′ = 0 where the amplitude of this radiation channel vanishes, Tm′ = 0. Once found, such a solution will be a true bound state at a purely real frequency and with no radiation.

Results

Photonic crystal slab in a homogeneous background

In this work we study two systems. The first one is a layered slab in a homogeneous medium (Fig. 1b). It consists of a sequence of dielectric rectangles of size d × h with permittivity εA, surrounded by a homogeneous material with permittivity εB. The eigenmodes in the homogeneous medium are simply plane waves with  and Θ being an identity matrix. In Fig. 2a, the region with one leaky channel (one real γm′) is shaded in yellow. In the slab, the Fourier coefficients of the permittivity is ξ1(n) = (d/a)(εA − εB) sin c (nd/a) + εBδn. For the basis truncation, we take M = 21 Fourier terms and eigenmodes (N = 10), which is enough for the results to converge within the frequency range we consider. As an example, we take εA = 4.9 (this is a reasonably small dielectric constant and is close to many common optical materials such as silicon nitride, zinc oxide, gallium nitride, indium tin oxide and diamond), εB = 1, d = 0.5a and h = 1.4a. By solving Eq. (8), we obtain the band structure Re(ω) and the quality factor Q = −ωr/(2ωi) of the resonances, shown as solid curves in Fig. 2a,b. As a validation, we also perform finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) simulations for the same structure. The FDTD simulations are carried out at a spatial resolution of 322 points per area of a2 (high enough for the calculated Q to converge) and take significantly longer than our method; the results, shown as circles in Fig. 2a,b, are in perfect agreement with our method.

and Θ being an identity matrix. In Fig. 2a, the region with one leaky channel (one real γm′) is shaded in yellow. In the slab, the Fourier coefficients of the permittivity is ξ1(n) = (d/a)(εA − εB) sin c (nd/a) + εBδn. For the basis truncation, we take M = 21 Fourier terms and eigenmodes (N = 10), which is enough for the results to converge within the frequency range we consider. As an example, we take εA = 4.9 (this is a reasonably small dielectric constant and is close to many common optical materials such as silicon nitride, zinc oxide, gallium nitride, indium tin oxide and diamond), εB = 1, d = 0.5a and h = 1.4a. By solving Eq. (8), we obtain the band structure Re(ω) and the quality factor Q = −ωr/(2ωi) of the resonances, shown as solid curves in Fig. 2a,b. As a validation, we also perform finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) simulations for the same structure. The FDTD simulations are carried out at a spatial resolution of 322 points per area of a2 (high enough for the calculated Q to converge) and take significantly longer than our method; the results, shown as circles in Fig. 2a,b, are in perfect agreement with our method.

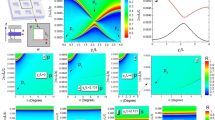

(a) Band structure and (b) quality factors of the guided resonances and BICs in the system illustrated in Fig. 1b. (a) Yellow shaded area is where there is only one leaky channel in the surrounding medium. The blue (green) solid curve is the dispersion of guided resonances that are even (odd) in x. BICs are marked with red plus signs: ① and ③ are protected by symmetry, while ② and ④ are not. Circles are FDTD simulation results. The grey curves are guided modes below the light line. Red dashed lines in (b) mark the location of BICs not protected by symmetry. (c) Electric field patterns of the BICs. (d) Magnitudes of the mode-expansion coefficients in the slab C (upper panel) and outside the slab T (lower panel) for the BIC ④. Red dots are components propagating in the x direction (where βm or γm is real); blue dots are evanescent components with imaginary wave vector along the x direction. The structural parameters are: εA = 4.9, εB = 1, h = 1.4a, d = 0.5a.

The quality factor diverges at the BICs. Non-symmetry-protected BICs occur at ky = 00.3156 (2π/a) for even-in-x modes (blue curve) and at ky = 0.1640 (2π/a) for odd-in-x modes (green curve). Symmetry protected BICs can be found at the Γ point (ky = 0), where radiation vanishes because Ez is odd in y for the resonance but even in y for the radiating wave. Such symmetry-incompatibility mechanism also holds at the edge of the Brillouin zone (ky = π/a), but at the zone edge of this system modes are either regular bound states (below the yellow shaded area) or states with multiple leaky channels (above the yellow shaded area) for which BICs are harder to come by. We will show zone-edge BICs in the second system. Fig. 2c shows the field profiles of the four BICs.

In Fig. 2d, we plot the coefficients C and T of the even-in-x non-symmetry-protected BIC. Inside the slab (upper panel), the amplitudes C are dominated by two propagating modes (shown in red). Outside the slab (lower panel), there is only one propagating mode and its amplitude vanishes at the BIC. The amplitude of the propagating mode outside the slab is the transmission from the in-slab modes, as shown in Eq. (11). Therefore, the disappearance of radiation arises from destructive interference of the transmission from the in-slab modes, which, as shown in the upper panel, primarily consist of two propagating modes.

Photonic crystal slab in a periodically-modulated background

The second system we consider is a PhC slab surrounded by a periodically-modulated background (Fig. 1c). The out-of-slab region has the same period as the slab but with a different filling fraction. We consider εA = 4.9, εB = 1, d1 = 0.5a, d2 = 0.2a, h = 1.4a. Figure 3a shows the band structure obtained from Eq. (8), with yellow shading over the region with one leaky channel ( ,

,  ); the corresponding quality factor is shown in Fig. 3b. Results from FDTD simulations are shown as circles in Fig. 3a,b; again the simulation results quantitatively agree with our method.

); the corresponding quality factor is shown in Fig. 3b. Results from FDTD simulations are shown as circles in Fig. 3a,b; again the simulation results quantitatively agree with our method.

(a) Band structure and (b) quality factors of the guided resonances in the system illustrated in Fig. 1c. The convention is the same as Fig. 2. BICs are labeled by numbers; among them ①, ③, ④ and ⑥ are protected by symmetry, while ② and ⑤ are not. (c) Electric field patterns of the BICs labeled by ②, ⑤, ⑥. The structural parameters are: εA = 4.9, εB = 1, h = 1.4a, d1 = 0.5a, d2 = 0.2a.

In this structure, symmetry-protected BICs can be found both at the Γ point (ky = 0) and at the zone edge (ky = π/a) inside the yellow-shaded region. The zone-edge BICs are possible because the periodic modulation in the background breaks the degeneracy of the propagating waves on the zone edge and opens up a finite yellow-shaded region where only one leaky channel is present. On the zone edge and within this region, the leaky wave is even under mirror flip around y = 0, but the BICs are odd (as can be seen from the mode profile in Fig. 3c) so they decouple from radiation. Meanwhile, non-symmetry-protected BICs still exist, as marked by red dashed lines in Fig. 3b and with the mode profiles shown in Fig. 3c.

In this system, we can observe an interesting phenomenon that two BICs annihilate at low-symmetry k points. On the odd-in-x band, as we vary the filling fraction in the background from d2/a = 0.23 to d2/a = 0.25, we observe that another non-symmetry-protected BIC emerges from the Γ point, moves along the ky axis and then annihilates with the other non-symmetry-protected BIC near ky = 0.14 (2π/a). The annihilation removes both BICs and leaves behind a finite peak in Q, as shown in Fig. 4a. The annihilation can be understood from the radiation coefficient T0, which we plot in Fig. 4b. Each zero-crossing of T0 corresponds to a BIC. Since T0 is expected to change continuously, two adjacent zero-crossings must have opposite slope and will cancel each other when they meet. This is an example of the topological charge of BICs18; here the two neighboring BICs have opposite charges and can annihilate with each other. Note that near the annihilation of the two BICs, quantitative prediction of the quality factor using FDTD becomes exceedingly hard due to an increased sensitivity on structural variations (which requires an unusually high spatial resolution in FDTD); nonetheless, we can still calculate Q efficiently with our method.

Annihilation of BICs.

(a) Quality factors and (b) radiation coefficient T0 of the odd-in-x band for varying filling fractions d2/a in the background. In (b), BICs not protected by symmetry are labeled by red plus signs, which correspond to the infinite-Q peaks in (a). Two such BICs annihilate each other near ky = 0.14 (2π/a) as d2/a increases past 0.25. The structural parameters are the same as Fig. 3 except for d2.

Discussion

In principle, more BICs can lie above the yellow shaded area in Figs 2a and 3a, where there are two or more radiation ports. In this case, three or more independent equations have to be satisfied simultaneously: f ′ = 0, T0 = 0, T1 =0 … It will require root-finding with more variables than ky and ω, which means the structure itself has to be fine-tuned to find BICs; such structure-sensitive BICs are less practical as experimental realization will be harder.

Our analysis of PhC slabs with 1D periodicity can be considered an extension of the previous topological vortex work18 to the 1D parameter space. As shown in Fig. 4b, here BICs correspond to nodal points where the radiation amplitude crosses zero (instead of vortex centers), which are manifestations of topological charges in 1D.

The preceding examples concern structures where the dielectric is real and symmetric in y, for which the matrices Hl are real symmetric and so the function f ′ is real-valued. However, BICs can exist in even more general systems. As long as  , Hl is real (although not necessarily symmetric and not necessarily Hermitian). In such PT-symmetric systems, if the non-Hermiticity is below the PT-breaking threshold, the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of Hl can still be real and the function f ′ can still be real-valued. Such systems can also support BICs. However, if the introduction of gain leads to lasing, one will need to account for the nonlinearity resulting from gain saturation37,38,39, which is beyond the linear model considered in this work.

, Hl is real (although not necessarily symmetric and not necessarily Hermitian). In such PT-symmetric systems, if the non-Hermiticity is below the PT-breaking threshold, the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of Hl can still be real and the function f ′ can still be real-valued. Such systems can also support BICs. However, if the introduction of gain leads to lasing, one will need to account for the nonlinearity resulting from gain saturation37,38,39, which is beyond the linear model considered in this work.

Conclusion

We have presented a mode expansion method that can efficiently and quantitatively describe guided resonances and BICs in PhC slabs and the method also reveals their underlying formation mechanisms. We find symmetry-protected BICs at the Γ point and at the zone edge, as well as BICs not protected by symmetry. The formalism is easily extendable and applicable to a wide range of structures. This is an attractive approach for the study of guided resonances and BICs in periodic structures.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Gao, X. et al. Formation mechanism of guided resonances and bound states in the continuum in photonic crystal slabs. Sci. Rep. 6, 31908; doi: 10.1038/srep31908 (2016).

References

Hsu, C. W., Zhen, B., Stone, A. D., Joannopoulos, J. D. & Soljačić, M. et al. Bound states in the continuum. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16048 10.1038/natrevmats.2016.48 (2016).

von Neumann, J. & Wigner, E. Über Merkwürdige Diskrete Eigenwerte. Phys. Z 30, 465 (1929).

Ulrich, R. Modes of propagation on an open periodic waveguide for the far infrared. Symposium on Optical and Acoustical Micro-Electronics 1, 359–376 (1975).

Plotnik, Y. et al. Experimental observation of optical bound states in the continuum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107(18), 183901 (2011).

Lee, J. et al. Observation and differentiation of unique high-Q optical resonances near zero wave vector in macroscopic photonic crystal slabs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109(6), 067401 (2012).

Hsu, C. W. et al. Observation of trapped light within the radiation continuum. Nature 499(7457), 188–191 (2013).

Weimann, S. et al. Compact Surface Fano States Embedded in the Continuum of Waveguide Arrays. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 240403 (2013).

Corrielli, G. et al. Observation of Surface States with Algebraic Localization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111 (2013).

Regensburger, A. et al. Observation of Defect States in PT-Symmetric Optical Lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, no. 22 (2013).

Fan, S. & Joannopoulos, J. D. Analysis of Guided Resonances in Photonic Crystal Slabs. Phys. Rev. B. 65 (2002).

Shipman, S. P. & Venakides, S. Resonant Transmission near Nonrobust Periodic Slab Modes. Phys. Rev. E 71 (2005).

Suh, W. et al. Displacement-Sensitive Photonic Crystal Structures Based on Guided Resonance in Photonic Crystal Slabs. Appl. Phys. Lett. 82, no. 13 (2003).

Marinica, D. C., Borisov, A. G. & Shabanov, S. V. Bound States in the Continuum in Photonics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100 (2008).

Liu, V., Povinelli, M. & Fan, S. Resonance-Enhanced Optical Forces between Coupled Photonic Crystal Slabs. Opt. Express 17 (2009).

Hsu, C. W. et al. Bloch Surface Eigenstates within the Radiation Continuum. Light-Sci. Appl. 2(7), e84 (2013).

Yang, Y. et al. Analytical Perspective for Bound States in the Continuum in Photonic Crystal Slabs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113 (2014).

Andreani, L. C. & Gerace, D. Photonic-crystal slabs with a triangular lattice of triangular holes investigated using a guided-mode expansion method. Phys. Rev. B. 73(23), 235114 (2006).

Zhen, B. et al. Topological Nature of Optical Bound States in the Continuum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, no. 25 (2014).

Bulgakov, E. N. & Sadreev, A. F. Bloch Bound States in the Radiation Continuum in a Periodic Array of Dielectric Rods. Phys. Rev. A 90, no. 5 (2014).

Bulgakov, E. N. & Sadreev, A. F. Light Trapping above the Light Cone in a One-Dimensional Array of Dielectric Spheres. Phys. Rev. A 92(2), 023816 (2015).

Porter, R. & Evans, D. V. Embedded Rayleigh-Bloch Surface Waves along Periodic Rectangular Arrays. Wave Motion 43 (2005).

Yang, B. J., Bahramy, M. S. & Nagaosa, N. Topological protection of bound states against the hybridization. Nat. Commun. 4, 1524 (2013).

Joannopoulos, J. D. et al. Photonic Crystals: Molding the Flow of Light. 2nd. Ch. 4–5, 44–92 (2008).

Zhou, W. et al. Progress in 2D Photonic Crystal Fano Resonance Photonics. Prog. Quant. Electron 38(1), 1–74 (2014).

Meier, M. et al. Laser action from two-dimensional distributed feedback in photonic crystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 74(1), 7–9 (1999).

Imada, M. et al. Coherent two-dimensional lasing action in surface-emitting laser with triangular-lattice photonic crystal structure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 75(3), 316–318 (1999).

Noda, S. et al. Polarization mode control of two-dimensional photonic crystal laser by unit cell structure design. Science 293(5532), 1123–1125 (2001).

Matsubara, H. et al. GaN photonic-crystal surface-emitting laser at blue-violet wavelengths. Science 319(5862), 445–447 (2008).

Hirose, K. et al. Watt-class high-power, high-beam-quality photonic-crystal lasers. Nat. Photonics 8(5), 406–411 (2014).

Yanik, A. A. et al. Seeing protein monolayers with naked eye through plasmonic Fano resonances. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 108(29), 11784–11789 (2011).

Zhen, B. et al. Enabling enhanced emission and low-threshold lasing of organic molecules using special Fano resonances of macroscopic photonic crystals[J]. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110(34), 13711–13716 (2013).

Foley, J. M., Young, S. M. & Phillips, J. D. Symmetry-protected mode coupling near normal incidence for narrow-band transmission filtering in a dielectric grating[J]. Phys. Rev. B. 89(16), 165111 (2014).

Friedrich, H. & Wintgen, D. Interfering Resonances and Bound States in the Continuum. Phys. Rev. A 32, 3231–3242 (1985).

Fan, S. et al. Theoretical Analysis of Channel Drop Tunneling Processes. Phys. Rev. B 59, no. 24, 15882–15892 (1999).

Kong, J. A. Electromagnetic Wave Theory. Ch. 7, 789–792, (2008).

Kim, C. S. et al. Resonant Tunneling in a Quantum Waveguide: Effect of a Finite-Size Attractive Impurity. Phys. Rev. B 60, no. 15, 10962–10970 (1999).

Türeci, H. E., Stone, A. D. & Collier, B. Self-consistent multimode lasing theory for complex or random lasing media. Phys. Rev. A 74(4) (2006).

Türeci, H. E., Ge, L., Rotter, S. & Stone, A. D. Strong interactions in multimode random lasers. Science 320(5876), 643–646 (2008).

Ge L., Chong, Y. D. & Stone, A. D. Steady-state ab initio laser theory: Generalizations and analytic results. Phys. Rev. A 82(6) (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by the Army Research Office through the Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies under contract no. W911NF-13-D-0001. B.Z. and M.S were partly supported (analysis and reading of the manuscript) by S3TEC, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the US Department of Energy under grant no. de-sc0001299. B.Z. was partially supported by the United States-Israel Binational Science Foundation (BSF) under award no. 2013508. C.W.H. was partly supported by the National Science Foundation through grant no. DMR-1307632. H.C., X.G. and X.L. were partly supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grants No. 61322501, No. 61574127 and No. 61275183, the Top-Notch Young Talents Program of China, the Program for New Century Excellent Talents (NCET-12-0489) in University, the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities and the Innovation Joint Research Center for Cyber-Physical-Society System.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.W.H., M.S. and H.C. conceived the study. X.G. and C.W.H. developed the theory and performed the computation and data analysis. X.G., C.W.H., B.Z., X.L., J.D.J., M.S. and H.C. discussed and interpreted the results and prepared the manuscript. C.W.H., M.S. and H.C. supervised the project.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, X., Hsu, C., Zhen, B. et al. Formation mechanism of guided resonances and bound states in the continuum in photonic crystal slabs. Sci Rep 6, 31908 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep31908

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep31908

This article is cited by

-

Thickness bound for nonlocal wide-field-of-view metalenses

Light: Science & Applications (2022)

-

Nonlinear response from optical bound states in the continuum

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Spectral characterization of silicon photonic crystal slab using out-of-plane light coupling arrangement

Applied Physics B (2018)

-

Tunability and Sensing Properties of Plasmonic/1D Photonic Crystal

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Anisotropy-induced photonic bound states in the continuum

Nature Photonics (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.