Abstract

High efficiency polymer:fullerene photovoltaic device layers self-assemble with hierarchical features from ångströms to 100’s of nanometers. The feature size, shape, composition, orientation and order all contribute to device efficiency and are simultaneously difficult to study due to poor contrast between carbon based materials. This study seeks to increase device efficiency and simplify morphology measurements by replacing the typical fullerene acceptor with endohedral fullerene Lu3N@PC80BEH. The metal atoms give excellent scattering contrast for electron beam and x-ray experiments. Additionally, Lu3N@PC80BEH has a lower electron affinity than standard fullerenes, which can raise the open circuit voltage of photovoltaic devices. Electron microscopy techniques are used to produce a detailed account of morphology evolution in mixtures of Lu3N@PC80BEH with the record breaking donor polymer, PTB7 and coated using solvent mixtures. We demonstrate that common solvent additives like 1,8-diiodooctane or chloronapthalene do not improve the morphology of endohedral fullerene devices as expected. The poor device performance is attributed to the lack of mutual miscibility between this particular polymer:fullerene combination and to co-crystallization of Lu3N@PC80BEH with 1,8-diiodooctane. This negative result explains why solvent additives mixtures are not necessarily a morphology cure-all.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Organic photovoltaics (OPV) have been intensely studied over the past two decades and have steadily made progress increasing the device efficiency. The breakthrough of the 10% efficiency mark has been achieved with both single and multi-junction cells1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Improved understanding of the local ordering and morphology of the component materials has been a large contributor to this steady improvement9,10,11,12,13,14.

A commonly studied high performing a polymer device is composed of poly({4,8-bis[(2-ethylhexyl) oxy]benzo[1,2-b:4,5-b] dithiophene-2,6-diyl}{3-fluoro-2-[(2-ethylhexyl)carbonyl] thieno[3,4-b] thiophenediyl}) (PTB7) and phenyl-C71-butric acid methyl-ester (PC70BM) with a processing additive diiodooctane (DIO) used for improved morphology and performance15,16,17,18. The DIO additive improves the power conversion efficiency (PCE) by at least a factor of two. The widely accepted reason for the improved performance is that the DIO decreases the component domain sizes from solution coating, thereby increasing interfacial area, exciton dissociation and the associated photocurrent19,20,21,22. DIO and other low volatility solvent additives have been widely reported in the OPV literature to decrease the polymer fullerene domain size by preventing liquid-liquid phase separation14. Reports on solvent mixtures always and without fail record an improvement in device function by use of a solvent additive. Due to the selection of positive results for published articles there are therefore no reports in which the use of a solvent additive results in poorer performance nor any analysis for why a solvent additive could result in a less advantageous morphology.

The nanoscale morphology of organic mixtures is very difficult to study due to lack of contrast between organic materials. Non-imaging techniques such as x-ray diffraction, neutron scattering, or various spectroscopies are typically used to infer average geometries and mixing ratios. Electron microscopy techniques are gaining popularity, but 2D images provide vertically averaged data. Tomography techniques can provide a 3D concentration map if sufficient contrast is available, if the reconstruction can avoid “missing wedge” artifacts and if the measurement can be performed without significant beam damage. We recently used electron tomography determine the relative location and volume of three distinct phases in an P3HT:fullerene OPV device with resolution of 1.5 × 1.5 × 1.5 nm. However, in order to create sufficient contrast for the measurement, an endohedral fullerene, Lu3N@C80-PCBEH (ethyl-hexyl), was used as a replacement for PCBM (see Fig. 1 for structure)23. Lu3N@C80-PCBEH has a lower electron affinity (EA) than PC70BM which results in increased open circuit voltage (VOC) and high device efficiencies in mixtures with the donor polymer P3HT24. In addition, Lu3N@C80-PCBEH is an excellent contrast agent for tomography measurements allowing for detailed nanoscale morphology measurements23.

Unfortunately, when combined PTB7 and Lu3N@C80-PCBEH yielded very low PCE devices. In fact, Lu3N@C80-PCBEH has been reported to produce poor OPV device efficiency with all OPV polymers other than P3HT25. The question is why? Several reports in literature report reduced PCE in polymer mixtures with the low EA acceptor ICBA and attribute the reduced efficiency to a reduction in charge separation driving force26,27. Other reports show that mixtures of ICBA mix more intimately with PTB7, which could increase the charge recombination28. Alternatively, it is reported that PC70BM forms a more favorable morphology with PTB7 than PC60BM, which could be an argument that a larger fullerene structure is desired for mixtures with PTB7. This article investigates the morphological changes due to the substitution of the endohedral fullerene as well as due to different processing additives using annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (ADF-STEM) combined with electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS), electron tomography (ET) and grazing incidence x-ray diffraction.

Since this article focuses on several electron microscopy techniques, we briefly review the origin of contrast and refer the reader to these references for more complete information. A transmission electron microscope (TEM) sends focused electrons through a thin sample and records a change in the intensity or energy of the electrons as a function of position. For a TEM the electrons are columnated over a area while for a scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) the electrons are focused into a <1 Å spot and rastered over the surface. For both techniques one can measure the bright field (total forward intensity), annular dark field (intensity of electrons scattered to high angle), or energy loss image (energy loss in a specific energy region) as a function of lateral position. The intensity in an ADF image scales approximately with the square of the atomic number so heavy atoms can be used as the contrast agent with heavier atoms appearing with higher intensity. A STEM-EELS image looks at the electron intensity at specific energy losses that correspond to specific elements. For our samples we use the energy loss for the Sulfur L-edge and for the Carbon K-edge, starting at 165 and 285 eV, respectively. EELS has a much lower signal to noise that ADF and so each pixel of each image takes more acquisition time. Supplemental Information Figure S1 shows a comparison of a STEM-EELS sulfur map, carbon map and ADF image P3HT/Lu3N@C80-PCBEH. This film was chosen because of the small features. In a typical STEM, each electron is accelerated to 200–300 keV which upon collision with the sample causes damage by impact. This type of beam damage causes vertical shrinkage of the film due to protons being “knocked off” of the sample, referred to as “knock on” damage. The other type of beam induced damage is caused by the electrons directly breaking chemical bonds, referred to as radiolysis, this effectively causes cross-linking in polymers. Finally ET refers to the process of taking many images of the same location at different angles with respect to the beam. The images are numerically reconstructed into a 3D volume. For ET, beam damage is a serious issue because the same area is imaged over 100 times. However, due to the high signal to noise of STEM-ADF imaging, the beam current and overall dose can be drastically reduced compared to conventional TEM-ET. While our group has measured high levels of beam damage for samples imaged using STEM-EELS-ET and previous reports of TEM-ET show vertical shrinkage of 30–50%29, measurements of shrinkage from STEM-ADF-ET are <1% for STEM-ADF-ET imaged samples.

Results

Film morphology as a function of fullerene size

The standard “high efficiency” PTB7/fullerene OPV devices is spin coated from a 97:3 vol% mixture of 1,2-dichlorobenzene (DCB) and DIO17,15. The DIO preferentially solubilizes the fullerene during the film drying process and results in a smaller scale phase separation. Chloronaphthalene (CN) is also a commonly used solvent additive in OPV mixtures. Like DIO, it has a low volatility and therefore evaporates slowly from the film. However, CN solubilizes both components and is reported to allow the polymer more time to crystallize, thus leading to more pure polymer phases, the opposite effect of DIO30. We compare films of 1:1 by wt. PTB7:PC60BM, PTB7:PC70BM PTB7:PC80BEH with spin coated from DSC with the CN and DIO additives.

Figures 2 and 3 show STEM-EELS sulfur maps and ADF-STEM images of PTB7:PC70BM and PTB7:PC60BM films, respectively. In both figures, films processed with DIO and CN additives are compared. The sulfur maps show brighter intensity where polymer content is higher and darker regions where fullerene content is higher because only the polymer has sulfur in its structure. Conversely, the ADF-STEM images show higher intensity where fullerene content is higher and lower intensity where polymer content is higher because the fullerene has higher volumetric electron density than the polymer. These images reveal that the fullerene domains are indeed ∼50 nm when DIO is used as an additive, where the CN additive causes much larger fullerene domains. Additionally, the PC70BM breaks up into smaller domains than the PC60BM31. This could be another reason PC70BM typically performs better than PC60BM in devices, in addition to increased optical absorption. Our measurements confirm that there is fullerene contained in the polymer-rich regions, but, the amount was not quantified here because this has already been published15. Other groups have shown that the composition of fullerene in the polymer matrix is ∼30% by volume PC70BM in films without DIO additive (i.e. the low efficiency films)15,16,17.

STEM/EELS sulfur maps (left) and ADF-STEM images (right) comparing PTB7:PC70BM films imaged over the same area.

The images correspond to fabrication with 3% DIO additive (top) and 3% CN (bottom). The bright areas in the EELS images correspond to polymer-rich domains. The bright areas in the ADF images correspond to fullerene-rich domains. The fullerene clusters are smaller in the DIO additive film (∼50 nm vs. ∼20 nm).

STEM/EELS sulfur maps (left) and ADF-STEM images (right) of two different PTB7:C60-PCBM films taken over the same area.

The images correspond to fabrication with 3% DIO additive (top) and 3% CN (bottom). The bright areas in the EELS image correspond to polymer-rich domains. The bright regions in the ADF images correspond to fullerene-rich domains. The fullerene clusters are smaller in the DIO additive film (∼100 nm vs. ∼500 nm).

Figures 2 and 3 demonstrate that our STEM measurements of PTB7 morphology yield domain sizes similar to that reported in the literature. These figures also demonstrate that better contrast is achieved with STEM-EELS sulfur maps than with ADF imaging in samples containing normal fullerenes.

Next, PTB7:Lu3N@C80-PCBEH films were fabricated in approximately the same volume ratio of polymer:fullerene as the 1:1 PTB7:PCBM weight ratio films. The density of Lu3N@C80-PCBEH has been measured to be 2.07 g/cm3 32, so a 1:1.5 PTB7:Lu3N@C80-PCBEH weight ratio film has the same volume ratio as a 1:1 PTB7/PCBM film. Three films were cast with different additives; no additive, 3% by volume CN and 3% DIO by volume. ADF-STEM images of these films are shown in Fig. 4. Due to the Lu content in the fullerenes, the contrast and practical resolution (image pixel size) in ADF imaged films, are for these samples, much higher than could be achieved using STEM-EELS.

ADF-STEM images of PTB7:Lu3N@C80-PCBEH films, with no additive (a) 3% CN (b) and 3% DIO (c). The images were collected with the same experimental conditions, (image intensity is indicative of local fullerene content) demonstrating there is very little to no fullerene in the polymer matrix in additive free (a) or DIO (c) processed films. However, the CN additive film (b) contains a substantial amount of fullerene in the polymer matrix. The part of the background in the DIO image (c) is boxed and the image contrast is increased to show finer details.

In the additive free and DIO additive films, there are large fullerene clusters several hundred nanometers across. There is also very little intensity coming from within the polymer matrix, indicating very little to no fullerene content. Comparing the ADF attenuation coefficient33 in these regions to that of a pure PTB7 film shows virtually no difference, indeed indicating there is little to no fullerene in the polymer matrix. This result that Lu3N@C80-PCBEH is much less miscible with PTB7 than PC70BM. There are also fullerene domains (∼50–100 nm across) which are clustered together in very large aggregates (order of μm) in the DIO additive film. Upon further investigation, it was determined that these fullerene aggregates are, at least, partially crystalline. This is contrary to what was found with the other PTB7:Lu3N@C80-PCBEH additive films as well as P3HT:Lu3N@C80-PCBEH where the fullerene always remained amorphous, despite extended annealing or solvent annealing23. The details indicates of the DIO additive morphology will be discussed in detail below.

In contrast to the no additive and DIO additive films, there is a substantial intensity in the polymer matrix in the 3% CN additive film, indicating a considerable amount of fullerene content in the polymer phase and vice-versa. Additionally, the fullerene clusters appear to have changed from domed shaped with no additive (inferred by the intensity) to blood-cell shaped with the addition of CN. The details of the CN additive morphology will be discussed in detail below.

3D morphology of DIO additive films

The improvements in PC60BM or PC70BM based films resulting from adding DIO raises the question of why, precisely, does DIO addition result in a decrease in material mixing in Lu3N@C80-PCBEH based films. Figure 4c show clear and substantial phase separation of PTB7 and Lu3N@C80-PCBEH. The Lu3N@C80-PCBEH domains have sharp edges suggesting the formation of crystals. The figure inset shows increased contrast in a dark region that consists of (within measurement limits) pure PTB7. The pure PTB7 film has ∼100 nm holes that correspond to thin spots. In our previous analysis of P3HT with various endohedral fullerenes, we showed that Lu3N@C80-PCBM crystallizes out of P3HT with heating and leaves behind similar thin-spots. In the previous study, we assumed that fullerene crystal formation occurred through Ostwald ripening of the crystal and simultaneous depletion of the amorphous fullerene domains. However since the diffusion rate of small molecule fullerenes is much higher than entangled polymers, the pattern of thin-spots in the polymer film indicates the pattern of depleted (removed) fullerene domains. The Lu3N@C80-PCBEH did not crystallize under any thermal conditions including long time solvent annealing with DCB and long time heating23. Referring again to the inset of Fig. 3c, there is a pattern of thin-spots in the polymer film with a diameter of 100–200 nm, which is consistent with the fullerene domain size found in PTB7/PC60BM and PTB7/PC70BM films that were deposited with DIO additive. This pattern suggests that Lu3N@C80-PCBEH also initially formed small domains with PTB7 upon spin coating from a mixed solvent but then later the Lu3N@C80-PCBEH was removed through an Oswald ripening process.

In Fig. 5, a higher magnification image of the Lu3N@C80-PCBEH crystallites is presented. The crystalline order is clear from simple observation. The inset shows fast Fourier transform (FFT) of Fig. 5 revealing the packing nature of the fullerene crystal. The d-spacings of the 010f, 100f and 110f reflections are 11.05, 10.10 and 7.22 ± 0.5 Å respectively. The formation of Lu3N@C80-PCBEH crystals was very unexpected due to the previous inability of the fullerene to crystallize as a pure substance, cast and annealed with various solvents in P3HT, or cast and annealed with various solvents in PTB723. In our study of Lu3N@C80-PCBEH with P3HT, the film was heated above the melting temperature and slow cooled for over 2 hours. There was not a single indication of fullerene crystallization and it was concluded that Lu3N@C80-PCBEH is less likely to crystallize that either PC60BM or PC70BM. We do not entirely rule out the possibility of pure Lu3N@C80-PCBEH crystals, but from our investigations this seems unlikely. Therefore, we speculatively conclude that the crystals observed in the DIO additive films are a co-crystal of Lu3N@C80-PCBEH and DIO.

To further investigate the structure of the DIO additive films, grazing incidence x-ray diffraction (GIXD) was performed. Figure 6 displays the diffraction patterns obtained from the pure components and mixed films. The reflections due to the PTB7 diffraction are in agreement with the previously reported pattern34. PTB7 lamella exhibit a preferred face-on orientation with respect to the substrate surface since the 100 Bragg-reflection is observed at 0.31 Å in the qy direction and the broad 010 π - π stacking peak is oriented at 1.7 Å along the qz direction. The pattern of amorphous Lu3N@C80-PCBEH exhibits three isotropic rings originating from the form factor of the fullerene molecules. The weak isotropic scattering signal of the polymer crystals is more pronounced in neat PTB7 films than in PTB7:Lu3N@C80-PCBEH films. On a first view, the corresponding intensities in the GIXD data of the sample with DIO additive seem to be enhanced dramatically. However, a closer view reveals that the azimuthal intensity distribution of the higher order peaks 200 and 300 are inhomogeneous. Furthermore, it turns out that the inhomogeneous intensity distribution is significantly different for the 200 and the 300 reflections. The scattering intensity maximum of the 300 peak are observed at 45° whereas the maximum of the 200 peak is observed at 0°. This finding indicates that the intensities found on the 200 and 300 Debye-Scherrer-rings do not correspond to an enhanced polymer crystallinity (see supporting information for more details).

GIXD detector images of pure Lu3N@C80-PCBEH (a) pure PTB7 (b) PTB7:Lu3N@C80-PCBEH with no additive (c) and PTB7:Lu3N@C80-PCBEH with 3% DIO added. The red sectors refer to the scattering rings of the amorphous fullerene and the white sectors refer to the reflections of the polymer crystals. Ovals mark the diffraction spots of the proposed oriented Lu3N@C80-PCBEH:DIO crystallites.

A homogeneous distribution of scattering intensity over the Debye-Scherrer-cone indicates the presence of amorphous fullerene (outlined in red) in the pure Lu3N@C80-PCBEH film, the PTB7:Lu3N@C80-PCBEH without additive film and the PTB7:Lu3N@C80-PCBEH with DIO film (Fig. 6a,c,d, respectively). However, additional Bragg-intensities of Lu3N@C80-PCBEH:DIO crystallites are observed additionally in the DIO additive film (outlined in Fig. 6d).

To resolve the origin of the extra intensity in the range of the 200 and 300 reflection, the STEM diffraction pattern for crystalline fullerene aggregates (Fig. 5) is taken into account. Assuming the formation of such fullerene crystals with a preferred orientation with the (100) plane in parallel to the substrate surface the enhanced intensities of the GIXD measurements can be explained to originate from the 010, 100 and 110 reflections of the fullerene crystals, respectively. A quantitative analysis gives d-spacings of 11.22, 9.97 and 7.57 Å for the 010f, 100f and 110f reflections, respectively, which is in good agreement to the values found by TEM analysis (cf. above). In a previous study of an endohedral fullerene with the same cage Lu3N@C80·(o-xylene) the lattice parameters a and b were determined to be 10.99(19) Å and 11.09(19) Å, respectively, which also nicely agrees to our results35. The fullerene crystals are obviously well ordered with respect to the substrate, which suggests that the fullerene crystallites are oriented to the face-on orientation of the PTB7 crystallites.

3-D morphology of CN additive films

The PTB7:Lu3N@C80-PCBEH films cast with no additive and with DIO additive (see Fig. 4) have almost no fullerene in the polymer matrix while the CN additive films show some mixing and also flattened fullerene rich domains. The darker center of the fullerene rich domains could indicate either reduced fullerene content or a reduction in layer thickness at the center of the fullerene domains. To determine if the fullerene domains have changed shape (rather than concentration) the sample thickness and ratio of polymer to fullerene must be determined at each location. A quantitative measurement of vertical fullerene concentration was made by comparing the sulfur signal from the mixed film to that of a pure PTB7 film and then dividing by the film thickness determined from the low loss plasmon (see Supporting information for more details). Kesava et al. previously measured the polymer:fullerene content of a mixed organic film successfully using EELS, but the normalization used here differs from that study slightly due to different film conditions36. Figure 7 shows the composition of the CN additive film, the colors represent the fraction of PTB7 present; two separate images of different locations are presented to show that the measurement is consistent. Large fullerene clusters (dark blue in Fig. 7) are present in both images, just as in seen in the ADF images of Fig. 4b. The PTB7 rich areas contain an average volume composition of 60 vol% PTB7: 40 vol% fullerene, where the fullerene-rich areas contain approximately 80% fullerene: 20% PTB7. This result is close to what is expected for the miscibility of PC60BM in PTB7 without a DIO additive15,16,17. These images revealed that the fullerene domains are thinner at the center and uniform in concentration. Fine details of the morphology in either PTB7 and Lu3N@C80-PCBEH domains cannot be resolved due to vertical averaging of the signal.

The CN additive film has an average of roughly 40% Lu3N@C80-PCBEH in the PTB7 matrix which should make a decent PV cell. However, the 2D images tell very little about the local morphology of fullerene in this region. To determine how the fullerene is distributed three-dimensionally, electron tomography utilizing the discrete algebraic reconstruction technique (DART) was used, as in previous work (see supporting information for more details)23,32. DART has been demonstrated to reduce some reconstruction artifacts, especially those related to the missing wedge of information due to missing tilt angles and to aid in the assignment of relative gray levels in mixed samples37,38.

Figure 8 shows the reconstruction of the two phases of a CN additive film, PTB7-rich (left) and fullerene-rich (right). The reconstruction reveals that the fullerene in PTB7-rich domains is not dispersed molecularly, as expected for PTB7:PC70BM, but is aggregated in very small (<5 nm) clusters. This clustering is consistent with low miscibility of Lu3N@C80-PCBEH in PTB7 seen from the additive-free film. The clusters of fullerene are only partially connected but may or may not be percolating (this is beyond the resolution capability of the ET reconstruction). The lack of a percolation network to the cathode would lead to poor charge collection in this film. The PTB7 phases in the fullerene rich domains also appear granular which means that the PTB7 is randomly dispersed in the fullerene and does not form any kind of internal structure.

Tomographic reconstruction of PTB7(left) and Lu3N@C80-PCBEH (right) from ADF-STEM tilt-series.

The reconstruction reveals the presence of small islands of fullerene which are connected, but not well connected to the electrodes. The presence of these small domains is likely the reason for the higher JSC of the CN additive films, but also the reason for their poor overall performance (compared to PTB7:PCBM), as the domains are not completely continuous to the electrodes.

The tomographic reconstruction is centered between four Lu3N@C80-PCBEH domains and represents the most co-planar location on the sample that we could locate. A DART reconstruction of a slab geometry film requires the assumption of complete co-planarity of the film interfaces and deviations from this are seen as reconstruction artifacts32. Evidence of these artifacts can be seen as blue shadows on the right and left side of the PTB7 rich domain near the Lu3N@C80-PCBEH domain edge. This shadow comes from changes in film thickness that cannot be numerically accounted for. Also, unlike in our previous work23,39, the phase composition cannot be accurately calculated because the average composition of the imaged area is unlikely to be the average composition of the film, due to the large fullerene aggregates.

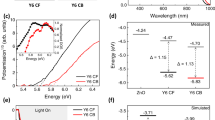

Correlation with Device Characteristics

Table 1 shows the device characteristics of PTB7:Lu3N@C80-PCBEH devices fabricated without additive and with 3% DIO and 3% CN additives. Surprisingly, the film with no additive performs the best overall. Even this device only shows a PCE of 0.4%, which is more that 20× lower than a high efficiency PTB7 OPV device. The DIO additive device is by far the worst as could be expected by the complete and large scale phase separation caused by the crystallization described above. For both the no-additive and 3% CN additive devices the Lu3N@C80-PCBEH fullerene increases the VOC by 0.15–0.3 V compared to devices fabricated using PC60BM or PC70BM. The increased mixing caused by addition of the CN additive does cause a relative increase of the JSC with respect to the no-additive sample, but not nearly as much as would be expected given the change in concentration.

The low JSC which is generated in PTB7:Lu3N@C80-PCBEH devices is certainly largely affected by the morphology. Evidence of reduced generation of separated charges at the polymer:fullerene interface using an endohedral fullerene compared to C60 or C70 has also been reported. Liedtke et al. demonstrated reduced charge generation by endohedral fullerenes by comparing the photoluminescence (PL) quenching of a P3HT:Lu3N@C80-PCBEH mixture to a P3HT:PC60BM mixture, showing that the quenching was lower in the endohedral fullerene mixture40. To investigate this possibility, the PL was measured for films of pure PTB7, PTB7:PC60BM, PTB7:Lu3N@C80-PCBEH with no additive, PTB7:Lu3N@C80-PCBEH with 3% CN added and PTB7:Lu3N@C80-PCBEH with 3% DIO added. The PL data is shown Supplemental Figure S7.

Discussion

The data presented above investigates the use of Lu3N@C80-PCBEH as an electron acceptor for OPV devices using the polymer PTB7 as a donor. Lu3N@C80-PCBEH is particularly interesting because (1) its reduced EA compared to other fullerenes, which could increase the VOC of OPV devices and (2) the metal center gives scattering contrast for electron microscopy that would allow nanoscale morphology measurements and (3) PTB7 showed better mixing with PC70BM than PC60BM which suggests that larger fullerenes could be an advantage.

Like many high performance co-polymers, the performance of OPV device mixtures with PTB7 and fullerenes is greatly improved by using a solvent additive in the casting mixture and in particular DIO. We show here that Lu3N@C80-PCBEH forms a co-crystal with DIO that causes the Lu3N@C80-PCBEH to be leeched out of the polymer film and thereby destroys the layer morphology. The inset to Fig. 3c provides insight into the mechanism for the crystal formation. The polymer film is shown to have thin spots that most likely were formed during the film formation process by the presence of Lu3N@C80-PCBEH rich domains. The domain size is typical of PC70BM fullerene films solution cast with a DIO additive. In other words the DIO additive seems to initially work as an emulsifier for Lu3N@C80-PCBEH into PTB7. DIO has a much lower vapor pressure than the main solvent, DCB and so as the film dries, the DIO content is enriched. Typically (and also here) the film is placed onto a hot plate at ∼50 °C to drive off the solvent more quickly. At this time it appears that crystals of Lu3N@C80-PCBEH nucleate. The orientation of the crystals is the same as the PTB7 polymer (Fig. 6) and so it is likely (though not proven) that these co-crystals nucleate on the PTB7 polymer. The co-crystals of Lu3N@C80-PCBEH and DIO are enlarged by transport of the Lu3N@C80-PCBEH through film that is swollen with DIO. The PTB7 is depleted of fullerene leaving behind thin spots where the Lu3N@C80-PCBEH clusters initially formed. Since the PTB7 is only solvated by the DCB solvent and its Tg is greater than 50 °C, it does not diffuse. This formation process of Lu3N@C80-PCBEH/DIO co-crystals explains why Lu3N@C80-PCBEH does not make good devices with most co-polymers that use DIO as a solvent additive. This is also a clear example that shows that DIO is not always an advantageous addition as it can lead to the formation of co-crystals.

We also examined the use of CN as a solvent additive. This solvent additive increased the miscibility of Lu3N@C80-PCBEH with PTB7 but phase separation on the micrometer length scale is still evident. As previously reported, the PTB7 polymer does not form pure polymer domains, but instead forms a mixed polymer/fullerene phase15. Figure 7 shows that PTB7 rich-domains are ∼40% fullerene by volume, which is theoretically enough to assure percolation of electrons to the electrodes. Figure 8 shows that the Lu3N@C80-PCBEH forms clusters within the PTB7 that may not be connected. The CN additive films had significantly lower fluorescence quenching than films without additive, but the improvements in JSC were only moderate and the VOC is reduced. These results suggest that recombination between PTB7 and Lu3N@C80-PCBEH is high and dominates the IV characteristics. One reason for high recombination could be that electrons are trapped in Lu3N@C80-PCBEH domains that do not connect to electrodes. Another could be poor charge separation due to insufficient electronic driving force. Finally, the Lu3N@C80-PCBEH rich domains dominate over 50% of the surface and have very little (∼20%) PTB7 content, so at least half of the film is not an effective photovoltaic device.

Conclusions

The morphology of mixed layers of the high-performance polymer PTB7 and an endohedral fullerene, Lu3N@C80-PCBEH, were investigated. The device performance was found to be inferior to PTB7:PCBM (either C60 or C70), even when using the widely accepted performance enhancing additive, diiodooctane. Electron microscopy studies revealed that in films with diiodooctane added, the fullerene strongly aggregated into micrometer sized crystals. Further investigation shows that the DIO initially solvates the Lu3N@C80-PCBEH but as the DIO slowly evaporates, co-crystals of Lu3N@C80-PCBEH and DIO form and ripen. The solvent additive chloronaphthalene causes the Lu3N@C80-PCBEH to partially disperse in the polymer matrix, but only in small, poorly connected clusters. The poor connectivity reduces the charge collection ability of the mixture compared to PC70 and PC60BM. Additionally, Lu3N@C80-PCBEH is less miscible with PTB7 than smaller fullerenes, leading to less effective quenching of PTB7 fluorescence than with a similar volume of PC60BM.

This work demonstrates important aspects of component mixing in organic photovoltaic mixtures. In particular, it is necessary that the fullerene component not crystallize because crystallization coupled with low vapor pressure solvents leads to phase separation of polymer and fullerene. Solvent additives and DIO in particular are universally credited with improved BHJ morphology. Here is an example in which the solvent additive causes phase separation through co-crystallization rather than allowing increased miscibility.

Experimental

Device Fabrication

Bulk-heterojunction devices were fabricated using PTB7 as the electron donor and Lu3N@C80PCBEH as the electron acceptor. Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate(PEDOT:PSS) was used as a hole transport layer. The standard device structure was as follows: ITO/PEDOT:PSS (AL4083)/PTB7: Lu3N@C80-PCBEH/Ca/Ag. ITO coated glass with a sheet resistance of 12.3 Ω/sq (Osram) was used as the transparent electrode. ITO was cleaned by ultrasonic treatment with acetone and isopropyl alcohol and dried under flow of dry nitrogen. A PEDOT:PSS (AL4083,H.C. Stark) solution was bladed at 50 °C onto clean substrates resulting in a thickness of approximately 40 nm as determined with Dektak profilometer. PEDOT:PSS layer was annealed for 15 min at 140 °C in a nitrogen filled glove box. The active layers consisting of PTB7 (7 mg/ml) and Lu3N@C80-PCBEH (12 mg/ml) were stirred at 80 °C for 12 h before use. The active layers were spin coated from o-DCB solution with different weight ratios onto the PEDOT: PSS layer. The samples were transferred to glove box and left under nitrogen atmosphere for overnight. A Ca (∼15 nm) and Ag (∼85 nm) top electrode was evaporated via a mask in vacuum onto the active layers with an electrode area of 0.104 cm2. PCE was calculated from J-V characteristics recorded with a Botest source measure unit. Illumination was provided by an Oriel Sol1A 94061 solar simulator with an intensity of 100 mW/cm2 where the light intensity was calibrated with a standard silicon photodiode.

STEM and ET

TEM specimens were prepared by floating the films off of PEDOT:PSS coated substrates in water and picking up the film with a lacey carbon coated Cu TEM grid. The films were imaged in a JEOL 2100-F at 200 kV. Tilt angles of ±70° were used for the ET study with a 1.5° saxton tilt scheme. The images were aligned manually in IMOD41. The reconstruction was performed using the DART algorithm within the ASTRA toolbox42 using 10 iterations; SIRT was used with as the internal algorithm using 30 iterations per DART iteration. The final reconstruction was determined by minimizing the projection error using two gray levels.

GIXD

The samples were measured with the highly customized Versatile Advanced X-ray Scattering instrument Erlangen (VAXSTER) at the chair for Crystallography and Structural Physics (Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany)43. The system was equipped with a Cu Kα (λ = 1.5418 Å;) Microfocus X-ray source (GeniX, 30 W, Xenocs, Sassenage, France). The beam was collimated by two automated double slit systems (aperture sizes 0.7 × 0.7 mm2 and 0.4 × 0.4 mm2) with a distance of about 1.2 m. The second slit system consists of four scatterless silicon single crystal blades. The sample was positioned inside the fully evacuated beam path in front of the 2D Pilatus3 300 K detector (Dectris Ltd., Baden, Switzerland). All GIXD measurements were performed at 22.2 °C. The collimation line was tilted and shifted with respect to the horizontal plane allowing grazing incidence angles which maximizes the scattering volume and enhances the scattered intensity. The incident angle α was set to 0.21 ± 0.032° which is just below the critical angle of total reflection of the substrate. The sampledetector distance was calibrated to 178.5 mm using a silver behenate standard, providing a beam size of about 0.5 × 15 mm2 at the sample position.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Roehling, J. D. et al. Nanoscale morphology of PTB7 based organic photovoltaics as a function of fullerene size. Sci. Rep. 6, 30915; doi: 10.1038/srep30915 (2016).

References

Green, M. A., Emery, K., Hishikawa, Y., Warta, W. & Dunlop, E. D. Solar cell efficiency tables (version 45). Progress in photovoltaics: research and applications 23, 1–9 (2015).

Service, R. Solar energy. outlook brightens for plastic solar cells. Science (New York, NY) 332, 293 (2011).

Liu, Y. et al. Aggregation and morphology control enables multiple cases of high-efficiency polymer solar cells. Nature communications 5, 5293 (2014).

He, Z. et al. Enhanced power-conversion efficiency in polymer solar cells using an inverted device structure. Nature Photonics 6, 591–595 (2012).

Li, N. & Brabec, C. J. Air-processed polymer tandem solar cells with power conversion efficiency exceeding 10%. Energy & Environmental Science 8, 2902–2909 (2015).

You, J. et al. 10.2% power conversion efficiency polymer tandem solar cells consisting of two identical sub-cells. Advanced Materials 25, 3973–3978 (2013).

You, J. et al. A polymer tandem solar cell with 10.6% power conversion efficiency. Nature communications 4, 1446 (2013).

He, Z. et al. Single-junction polymer solar cells with high efficiency and photovoltage. Nature Photonics 9, 174–179 (2015).

Brédas, J.-L., Norton, J. E., Cornil, J. & Coropceanu, V. Molecular understanding of organic solar cells: the challenges. Accounts of chemical research 42, 1691–1699 (2009).

Yin, W. & Dadmun, M. A new model for the morphology of p3ht/pcbm organic photovoltaics from small-angle neutron scattering: rivers and streams. Acs Nano 5, 4756–4768 (2011).

Ma, W. et al. Domain purity, miscibility and molecular orientation at donor/acceptor interfaces in high performance organic solar cells: paths to further improvement. Advanced Energy Materials 3, 864–872 (2013).

Schmidt-Hansberg, B. et al. Moving through the phase diagram: morphology formation in solution cast polymer-fullerene blend films for organic solar cells. Acs Nano 5, 8579–8590 (2011).

Treat, N. D. et al. Microstructure formation in molecular and polymer semiconductors assisted by nucleation agents. Nature materials 12, 628–633 (2013).

van Franeker, J. J., Turbiez, M., Li, W., Wienk, M. M. & Janssen, R. A. A real-time study of the benefits of co-solvents in polymer solar cell processing. Nature Communications 6, 6229 (2015).

Collins, B. A. et al. Absolute measurement of domain composition and nanoscale size distribution explains performance in ptb7:pc71bm solar cells. Advanced Energy Materials 3, 65–74 (2013).

Liu, F. et al. Understanding the morphology of PTB7:PCBM blends in organic photovoltaics. Advanced Energy Materials 4, 1301377 (2014).

Hedley, G. J. et al. Determining the optimum morphology in high-performance polymer-fullerene organic photovoltaic cells. Nature Communications 4, 1–10 (2013).

Foster, S. et al. Electron collection as a limit to polymer:PCBM solar cell efficiency: Effect of blend microstructure on carrier mobility and device performance in PTB7:PCBM. Advanced Energy Materials 4, 1400311 (2014).

Zusan, A. et al. The effect of diiodooctane on the charge carrier generation in organic solar cells based on the copolymer pbdttt-c. Scientific reports 5 (2015).

Kyaw, A. K. K. et al. Effects of solvent additives on morphology, charge generation, transport and recombination in solution-processed small-molecule solar cells. Advanced Energy Materials 4 (2014).

Guo, S. et al. Influence of solvent and solvent additive on the morphology of ptb7 films probed via x-ray scattering. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 118, 344–350 (2013).

Gao, F. et al. The effect of processing additives on energetic disorder in highly efficient organic photovoltaics: A case study on pbdttt-c-t: Pc71bm. Advanced Materials (2015).

Roehling, J. D., Batenburg, K. J., Swain, F. B., Moulé, A. J. & Arslan, I. Three-dimensional concentration mapping of organic blends. Advanced Functional Materials 23, 2115–2122 (2013).

Ross, R. B. et al. Endohedral fullerenes for organic photovoltaic devices. Nature Materials 8, 208–212 (2009).

Walker, K. & Joslin, S. High efficiency organic solar cells. Tech. Rep. (2011).

Kang, T. E. et al. Photoinduced charge transfer in donoracceptor (da) copolymer: Fullerene bis-adduct polymer solar cells. ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces 5, 861–868 (2013).

Faist, M. A. et al. Understanding the reduced efficiencies of organic solar cells employing fullerene multiadducts as acceptors. Advanced Energy Materials 3, 744–752 (2013).

Cheng, P., Lia, Y. & Zhan, X. Efficient ternary blend polymer solar cells with indene-C60 bisadduct as an electron-cascade acceptor. Energy & Environmental Science 7, 2005–2011 (2014).

van Bavel, S. S. & Loos, J. Volume organization of polymer and hybrid solar cells as revealed by electron tomography. Advanced Functional Materials 20, 3217–3234 (2010).

Lee, J. K. et al. Processing additives for improved efficiency from bulk heterojunction solar cells. Journal of the American Chemical Society 130, 3619–3623 (2008).

Collins, B. A., Li, Z., McNeill, C. R. & Ade, H. Fullerene-dependent miscibility in the silole-containing copolymer psbtbt-08. Macromolecules 44, 9747–9751 (2011).

Roehling, J. D. et al. Material profile influences in bulk-heterojunctions. Journal of Polymer Science B: Polymer Physics 52, 1291–1300 (2014).

Van den Broek, W. et al. Correction of non-linear thickness effects in haadf stem electron tomography. Ultramicroscopy 116, 8–12 (2012).

Hammond, M. R. et al. Molecular order in high-efficiency polymer/fullerene bulk heterojunction solar cells. ACS Nano 5, 8248–8257 (2011).

Stevenson, S. et al. Preparation and crystallographic characterization of a new endohedral lu3n@c80·(o-xylene) and comparison with sc3n@c80·(o-xylene). Chemistry a European Journal 8, 4528–4535 (2002).

Kesava, S. V. et al. Domain compositions and fullerene aggregation govern charge photogeneration in polymer/fullerene solar cells. Advanced Energy Materials 4, 1400116 (2014).

Chen, D. et al. The properties of SIRT, TVM and DART for 3d imaging of tubular domains in nanocomposite thin-films and sections. Ultramicroscopy 147, 137–148 (2014).

Goris, B., Roelandts, T., Batenburg, K., Mezerji, H. H. & Bals, S. Advanced reconstruction algorithms for electron tomography: from comparison to combination. Ultramicroscopy 127, 40–47 (2013).

Wodo, O., Roehling, J. D., Moulé, A. J. & Ganapathysubramanian, B. Quantifying organic solar cell morphology: a computational study of three-dimensional maps. Energy & Environmental Science 6, 3060 (2013).

Liedtke, M. et al. Triplet exciton generation in bulk-heterojunction solar cells based on endohedral fullerenes. Journal of the American Chemical Society 133, 9088–9094 (2011).

Kremer, J. R., Mastronarde, D. N. & McIntosh, J. R. Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. Journal of structural biology 116, 71–76 (1996).

van Aarle, W. et al. The astra toolbox: A platform for advanced algorithm development in electron tomography. Ultramicroscopy (2015).

Schmiele, M., Gehrer, S., Westermann, M., Steiniger, F. & Unruh, T. Formation of liquid crystalline phases in aqueous suspensions of platelet-like tripalmitin nanoparticles. The Journal of Chemical Physics 140, 214905 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This research project was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation under Award No. 1436273. TU and TK greatly acknowledge the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Cluster of Excellence: Engineering of Advanced Materials) for financial support. TA and CB acknowledge the financial support of Solar Technologies go Hybrid (SolTech) and SFB 953 (Synthetic Carbon Allotropes). JDR thanks the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract DE-AC52-07NA27344 for salary support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.D.R. and J.S. in the group of A.J.M. performed all microscopy experiments. Microscopy data interpretation was performed by J.D.R. and T.K. is in the research group of T.U. where all GIXD measurements and data interpretation occured. D.B. and T.A. are in the research group of C.J.B. where the samples were fabricated and where efficiency measurements and fluorescence measurements occured. The manuscript was written primarily by J.D.R. and A.J.M. and significant input from all authors.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Roehling, J., Baran, D., Sit, J. et al. Nanoscale Morphology of PTB7 Based Organic Photovoltaics as a Function of Fullerene Size. Sci Rep 6, 30915 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep30915

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep30915

This article is cited by

-

Optical, film surface and photovoltaic properties of PTB7-Fx-based polymer-organic solar cells prepared in ambient conditions

Chemical Papers (2018)

-

Morphological studies of small-molecule solar cells: nanostructural engineering via solvent vapor annealing treatments

Journal of Materials Science (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.