Abstract

T1C-19 is newly developed transgenic rice active against lepidopteran pests and expresses a synthesized cry1C gene driven by the maize ubiquitin promoter. The brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens, is a major non-target pest of rice and the rove beetle (Paederus fuscipes) is a generalist predator of N. lugens nymphs. As P. fuscipes may be exposed to the Cry1C protein through preying on N. lugens, it is essential to assess the potential effects of transgenic cry1C rice on this predator. In this study, two experiments (a direct feeding experiment and a tritrophic experiment) were conducted to evaluate the ecological risk of cry1C rice to P. fuscipes. No significant negative effects were observed in the development, survival, female ratio and body weight of P. fuscipes in both treatments of direct exposure to elevated doses of Cry1C protein and prey-mediated exposure to realistic doses of the protein. This indicated that cry1C rice had no detrimental effects on P. fuscipes. This work represents the first study of an assessment continuum for the effects of transgenic cry1C rice on P. fuscipes. Use of the rove beetle as an indicator species to assess potential effects of genetically modified crops on non-target arthropods is feasible.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rice (Oryza sativa L.) is one of the most important staple foods in the world. More than 50% of the world population (or more than 3 billion people) depend on rice for their daily lives1. The annual total planting area for rice was 29.4 million hectares in China for 2006 and China produced 29% of the world’s rice2,3. However, rice in China suffers from many insect pests, including planthoppers, Nilaparvata lugens (Stål), Sogatella furcifera (Horváth) and Laodelphax striatellus (Fallen); rice borers, Chilo suppressalis (Walker) and Tryporyza incertulas (Walker). In some regions, the water weevil Lissorhoptrus oryzophilus Kuschel, the gall midge Orseolia oryzae (Wood-Mason) and the thrip Chloethrips oryzae (Wil.) also heavily infest rice4.

To meet demands for feeding its growing population and replacing the intense utilization of insecticides in controlling pests, China has devoted great efforts to develop insect-resistant genetically modified (GM) rice lines5,6. Although no GM rice line has yet been commercialized, many transgenic lines expressing Bt proteins against lepidopteran pests, for example those expressing cry1Ab, cry1Ac, cry2Aa, cry1Fa and cry1Ca have been developed and these exhibit high resistance against lepidopteran target pestss7,8,9. To avoid potential risks to the environment associated with cultivating GM plants, any new GM plant needs to undergo a rigorous environmental risk assessment prior to its approval for commercial cultivation. An important part of this assessment, especially in the case of insect-resistant GM plants, is the evaluation of potential effects on valued non-target organisms6,10.

The brown planthopper (BPH), Nilaparvata lugens, is the important herbivorous insect of rice by sucking the phloem sap and causes huge yield loss11,12,13. It lives in rice paddies and is a significant aggressive predator of N. lugens14. It lives in the rice paddy and is recognized as a significant aggressive predator of N. lugens15. Since P. fuscipes is likely to be exposed to Cry proteins in rice fields by preying on N. lugens, the potential effects of transgenic Bt rice on this non-target natural predator should be evaluated case-by-case prior to the commercialization of transgenic Bt rice.

The Bt rice line T1C-19 expresses Cry1C protein and shows high resistance against rice leaf folder, Cnaphalocrocis medinalis Guenee16. Based on the risk assessment guidelines for insect-resistant GM crops, impacts of transgenic cry1C rice on non-target predators have already been evaluated. Laboratory studies indicated that larvae and adults of Chrysoperla subpiraticus (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae) are not sensitive to Cry1C proteins when provided in artificial diets or Bt rice pollen17. Chrysoperla sinica is a prevalent predator species in Chinese rice fields, its larvae may consume planthoppers and its adults feed primarily on pollen, honeydew and nectar18. High dosage of Cry1C proteins in the artificial diet had no detrimental impacts on the life-table parameters of Propylaea japonica (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) and hence the growing of transgenic cry1C rice should pose a negligible risk to P. japonica19. P. japonica is a common and abundant predator in rice paddy, both the larvae and adults consume thrips, eggs and young larvae of Lepidoptera and the adults also feed on rice pollen20,21. Cry1C had no significant adverse effects on the population dynamics of arthropod predators13,22. However, there are no reports concerning impacts of Cry1C on P. fuscipes.

In this study, a tritrophic bioassay was conducted to assess whether T1C-19 plants had prey-mediated effects on the life-table parameters of P. fuscipes, when P. fuscipes preyed on N. lugens nymphs fed on T1C-19. The biotransfer of Cry1C protein expressed in T1C-19 rice to N. lugens and its subsequent transfer to P. fuscipes was investigated. To further verify whether Cry1C protein had any direct toxicity to P. fuscipes, a Tier-1 bioassay was performed in which P. fuscipes adults were fed an artificial diet incorporating purified Cry1C protein at a level much higher than that likely to be encountered under field conditions. Also, this study was to explore whether Cry1C protein could be transferred to P. fuscipes through BPH by Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Results

Effects of prey sources on the survival and development of P. fuscipes

The whole preimaginal development of P. fuscipes fed N. lugens nymphs was 28.9 d (Table 1). When incorporated with Drosophila melanogaster adults, the first instar, second instar, pupa and whole preimaginal durations were significantly shortened (P < 0.05) (Table 1). However, the preimaginal survival rate, sex ratio and female and male weight were not significantly affected by prey source (P > 0.05) (Table 1). The results showed that the food combination containing N. lugens nymphs added with D. melanogaster adults could shorten preimaginal stage duration of P. fuscipes.

Impact of different artificial feeding system on development of P. fuscipes

Compared to P. fuscipes larvae fed the artificial diet only, the larval survival rate increased from 52.0 to 68.0% (P = 0.046) when their artificial diet incorporated nymphs of N. lugens (Table 2). The first and second instar larvae, pre-pupa and whole preimaginal durations were significantly shortened (P < 0.05) and the female body weight increased significantly (P < 0.05) (Table 2). When not provided with the artificial diet, a group of 45 P. fuscipes larvae all died within 6 d, indicating that they could not survive by feeding only on humus of soil. The results showed that if P. fuscipes larvae developed into adults, they must have consumed the artificial diet, which could then be used as a medium to deliver Bt protein into P. fuscipes.

Life-table parameters of P. fuscipes fed on transgenic cry1C rice

There were no significant differences in preimaginal developmental time, preimaginal survival, female ratio, pre-oviposition, total fecundity and fresh body weight between P. fuscipes reared with first to third instar nymphs of brown planthopper fed on transgenic cry1C rice compared with non-Bt rice (P > 0.05) (Table 3).

Cry1C protein detection in rice plants, larvae of N. lugens and P. fuscipes

ELISA assay showed that the concentration of Cry1C protein in rice sheaths was 1.8 ± 0.09 μg/g fresh weight. When first to third instar nymphs of N. lugens were reared on Bt rice, the Cry1C protein concentration in nymphs was 1.1 ± 0.0 ng/g. When P. fuscipes larvae preyed on first to third instar N. lugens nymphs fed on T1C-19, no Cry1C protein was detected in newly emerged P. fuscipes adults (Fig. 1).

Purified Cry1C protein bioassay and life-table parameters of P. fuscipes

The Cry1C concentrations in the artificial diets were 12.4 ± 0.9 and 11.5 ± 0.1 μg/g, respectively, before and after exposure to P. fuscipes for 24 h. No significant differences were observed in the Cry1C concentration in diets (the Cry1C concentration decreased by 7.2%) before and after exposure (Student’s t-test, P = 0.422). This indicated that Cry1C concentration was stable in the artificial diets throughout the feeding process.

The LC50 (concentration resulting in 50% mortality) of this batch of Cry1C for Plodia interpunctella larvae was 0.03 μg/g fresh weight. Before and after exposure to P. fuscipes for 24 h, the mortalities of C. medinalis larvae were 55.6% and 48.9%, respectively, fed on the artificial diets with 50 μg/g Cry1C potein. However, the mortality of C. medinalis larvae was 17.8% after feeding on the pure artificial diet. The results suggested that the artificial diets with Cry1C protein had insecticidal activity for P. fuscipes.

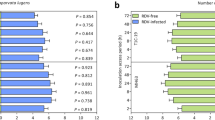

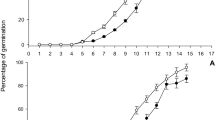

Significantly lower survival rate was observed in P. fuscipes fed on artificial diet containing 1 mg/g potassium arsenate (PA) relative to the pure artificial diet (P < 0.001, Fig. 2). No significant difference (P = 0.729, χ2 = 0.1210, d.f. = 1) was detected in the larval survival rate of P. fuscipes fed an artificial diet containing 50 μg/g Cry1C protein compared with pure artificial diet (Table 4). Similarly, no differences were found in the developmental duration, preimaginal survival rate and female ratio of P. fuscipes with high dosage of Cry1C compared to the pure artificial diet (Table 4).

Discussion

Rove beetle (P. fuscipes) is widely distributed in all temperate and tropical continents23. It lives in humid habitats such as marshes, edges of freshwater lakes and streams and rice fields14,24. It preys on soft-bodied insect pests such as aphids, whitefly, mites, maggots of fruit fly and leaf hoppers of different crops25. Both the larvae and adults of P. fuscipes forage for food on the foliage or among tillers of rice plants26. They are important predators in rice fields and effective biological control agents against N. lugens, which is the most important pest in tropical rice fields and the main non-target insect pest in Bt rice fields27. Bt protein could expose the predator P. fuscipes insects through predation of the non-target herbivores N. lugens. Therefore, P. fuscipes is a good surrogate for non-target arthropods (NTAs) and it is vital to evaluate the effects of Bt rice on P. fuscipes prior to any commercialization. There are few reports on safety evaluation of Bt crops on P. fuscipes. There was no impact on the survival and predation function of adult P. fuscipes fed N. lugens reared with transgenic cry1Ac/cry1Ab rice in laboratory studies28; and the Cry1Ab protein expressed by maize hybrid MON810 did not influence the overall community structure of the rove beetle in a field experiment29.

Romeis et al.10 and Yu et al.30 descried the ecological risk assessment of transgenic plant for NTAs. In the present study, the ecological risk of transgenic cry1C rice to P. fuscipes was developed by two experiments: (1) a direct feeding experiment, in which P. fuscipes was fed an artificial diet containing Cry1C at a dose 10 times that it may encounter in realistic field conditions; and (2) a tritrophic experiment, in which the Cry1C protein was delivered to P. fuscipes indirectly through preying on N. lugens nymphs. The transgenic cry1C rice and Cry1C protein had no significant detrimental effects on the developmental time, preimaginal survival, female ratio and body weight of P. fuscipes. This is the first report of an assessment continuum for the effects of transgenic cry1C rice on P. fuscipes.

“Tier-1 assays” is the initial step to determine the potential hazard or toxicity of the insecticidal compound produced by GE plants, such as a Cry protein, to selected test species31. In the present study, a direct feeding experiment was carried that purified Cry1C protein was fed to P. fuscipes larvae by reference to the method of Zhou32. We selected artificial diets combining nymphs of N. lugens to deliver Cry1C protein into P. fuscipes. The oral poison potassium arsenate (PA), as a positive control, was used to verify the dietary exposure assay. This experiment showed that significantly lower survival was found in P. fuscipes fed on artificial diet containing 1 mg/ml PA relative to those fed on pure artificial diet, which indicated the test system in this experiment could be used to detect the dietary effects of insecticidal compounds potassium arsenate. No negative effect was found in the life-table parameters of P. fuscipes when provided with the artificial diet containing Cry1C at a concentration 10 times that for actual exposure concentration in the field compared with the pure artificial diet (negative control). Our experiment was the first report to evaluate the potential toxicity effect of Cry1C on P. fuscipes by use of “Tier-1 assays”.

The present study showed that different prey sources affected development of P. fuscipes. The experiment started with 50 P. fuscipes larvae when fed on N. lugens. To ensure enough prey samples, 80 P. fuscipes larvae fed on N. lugens added D. melanogaster as a supplement. The results showed that feeding P. fuscipes with both N. lugens nymphs and D. melanogaster adults significantly shortened growth duration, compared to feeding P. fuscipes with only N. lugens nymphs. This is consistent with Bong’s findings that survival and adult fecundity of P. fuscipes were negatively affected when lobster cockroach Nauphoeta cinerea (Olivier) was used as the only food resource33. Many reports have also shown that different nutritional composition of prey may alter biological parameters of predators34,35,36,37.

Brown planthopper is the important non-target herbivore in transgenic Bt rice. It piercing and sucking phloem of rice. Bt proteins of transgenic rice could be transferred to it via feeding38. However, whether Bt protein could be transferred to predators of brown planthopper are controversial. Cry1Ab and Cry2A could be transferred to Cyrtorhinus lividipennis and Hylyphantes graminicola by predation on brown planthopper fed on transgenic Bt rice39,40. While Cry2A protein could not be transferred to C. sinica and C. lividipennis via preying N. lugens fed on transgenic Bt rice38. In the current study, Cry1C also could not be transferred to P. fuscipes via predation of N. lugens. Even different predators preying N. lugens fed on the same transgenic Bt rice containing different concentration of Bt protein in the body. Further study should be focused on whether this difference is caused by the different feeding behavior of predator.

Our study was the first to elaborate the effects of transgenic cry1C rice on P. fuscipes, a predator in rice ecosystems and utilized a Tier-1 examination system and tritrophic bioassay. The results indicated that P. fuscipes was not sensitive to Cry1C protein and transgenic cry1C rice (T1C-19) poses a negligible risk to N. lugens.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

The transgenic rice line, T1C-19 and its corresponding non-transformed parental rice Minghui 63 were used for the experiments. T1C-19 expresses a gene encoding synthetic cry1C under the control of the corn ubiquitin promoter and exhibits high resistance to stem borers and leaffolders16. Both rice lines were obtained from National Key Laboratory of Crop Genetic Improvement, Huazhong Agricultural University (Wuhan, China). The culture methods of both rice lines for the laboratory experiments were described by Han et al.38 and Yoshida et al.41.

N. lugens and P. fuscipes

The original adults of N. lugens were randomly collected from paddy fields in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China. Prior to the tritrophic bioassay, N. lugens were reared on T1C-19 and Minghui 63, respectively, for more than ten generations to obtain uniform colonies. N. lugens was fed on 15-day-old rice seedlings cultured with Yoshida solution in plastic tanks.

The original individuals of P. fuscipes were also randomly collected from paddy fields in Xiaogan city. Both artificial diets and N. lugens nymphs were supplied to P. fuscipes larvae as their food source and maintained in the laboratory for more than one generation. The larvae were reared in plastic containers (22 cm length × 7 cm width × 7 cm height) covered with nylon mesh on the open end. First, a piece of wetted sponge was placed at the bottom of the container to maintain humidity, then the container was filled up to 2–2.5 cm with soil (damp soil rich in humus for raising maize) to provide a natural environment. There were 30–50 rice seedlings put into the container to feed N. lugens nymphs (100–300 first–third instar) and the roots of rice seedlings were supplied with moist cotton to maintain moisture. Meanwhile, artificial diets were put on a glass slide that was placed on the soil. In each container, 20–50 larvae of P. fuscipes were reared. The artificial diet was refreshed daily and at least 100 nymphs of N. lugens were supplied into each container daily. The artificial diet was prepared as described by Zhou32 with some modification. Liver powder purchased from Nutritional Food Co. Ltd., Yi Wei, China, Product Code: 1047457832 (specification: 3.5 g × 15 package; nutrient content: pork liver 50%, chicken liver 20%, goose liver 15%, jujube 10% and galacto-oligosaccharides 5%) and honey (acacia honey from Kangsi farmers, net 450 g, Huazhong Agricultural University) were mixed at the ratio of 5:1 and stirred with a glass rod for 1 min or more.

Newly-eclosed adults were picked out with a brush and reared in a glass beaker. The P. fuscipes adults were supplied with both N. lugens nymphs and with artificial diets. Into a 100-mL glass beaker, 200 rice seedlings were placed and reared with Yoshida culture solution and 200–400 N. lugens nymphs were raised on the rice seedlings. Then, this glass beaker was placed inside a 2000-mL glass beaker (with a piece of wetted sponge at the bottom to maintain humidity), as also was a glass Petri dish (5 cm diameter × 5 cm height) holding the artificial diet. The females laid eggs on sponge and rice seedlings. After 5 days of oviposition, the sponge and rice seedlings were transferred to a plastic container (22 cm length × 7 cm width × 7 cm height), with wetted tampons to maintain humidity. When larvae hatched, they were transferred to a plastic container for larvae rearing as described previously. All the insects were cultured and all experiments were conducted in a climatic chamber at 28 ± 1 °C, relative humidity 70 ± 5% and a light/dark cycle of 14/10 h.

Effects of prey sources on survival and development of P. fuscipes

Because P. fuscipes is a polyphagous predator in rice fields, before we conducted the prey-mediated effects of transgenic cry1C rice on P. fuscipes, it was essential to evaluate the effects of a single prey source on survival and development of P. fuscipes. If the single prey source had negative impacts on P. fuscipes, then another prey source should be added to minimize the negative effects. Therefore, two kinds of prey were supplied to P. fuscipes. Newly hatched larvae of P. fuscipes (<24 h) were put individually into glass tubes (2 cm diameter × 12 cm length) sheathe with nylon mesh. In order to maintain humidity, each glass tube was filled with a piece of wetted sponge in the bottom: (i) 9–10 nymphs of N. lugens (first–third instar), reared on TN1 rice plants, were used daily as the prey of P. fuscipes; (ii) in addition to 9–10 N. lugens nymphs daily, two adults of D. melanogaster (supplying one adult of D. melanogaster at 2 d after P. fuscipes neonates hatched, 2d at second-instar larvae of P. fuscipes, respectively) were also employed as prey of P. fuscipes. The survival and ecdysis of insects were recorded daily. Sex and body weight of rove beetle were recorded after P. fuscipes adults were emerged.

Effects of different artificial rearing system on the survival and development of P. fuscipes

Newly hatched larvae (<48 h) of P. fuscipes were individually reared in Petri dishes (5 cm diameter × 5 cm height) to evaluate whether the artificial diets met the growth and development demands of P. fuscipes and whether the P. fuscipes larvae could survive by only feeding on humus in soil. Each Petri dish contained damp soil rich in humus (1 cm in thickness) at the bottom and three different artificial rearing systems were constructed: (i) damp soil only; (ii) damp soil and artificial diet; and (iii) damp soil and artificial diet plus nymphs of N. lugens (supplying 10 nymphs of N. lugens at 6, 7 and 8 d after P. fuscipes feeding artificial diets, respectively). The survival and ecdysis of insects were recorded daily. Sex and body weight of rove beetle were recorded after P. fuscipes adults were emerged.

Effects of Bt-rice on the life-table parameters of P. fuscipes fed on N. lugens nymphs

Newly molted first instar larvae (<24 h) of P. fuscipes were put individually into glass tubes (2 cm diameter × 12 cm height) covered with nylon mesh. In order to maintain humidity, each glass tube was filled with a piece of wetted sponge in the bottom. One 15-d-old rice seedling was introduced into the glass tube as food for 9–10 (first–third instar) nymphs of N. lugens. Therefore, P. fuscipes larvae could prey on N. lugens nymphs. The rice seedlings and nymphs of N. lugens were changed daily. Two adults of D. melanogaster (supplying one adult of D. melanogaster at 2 d after P. fuscipes neonates hatched, 2 d at second-instar larvae of P. fuscipes respectively) were also employed as prey of P. fuscipes. The survival and ecdysis of P. fuscipes nymphs were monitored every day. The sex and body weight of P. fuscipes adults were recorded upon emergence of adults. For each rice line, 80 larvae of P. fuscipes were tested. Upon early emergence of the P. fuscipes, male and female were paired and reared in in a plastic petri dish (9cm in diameter) that contained a moist filter paper and was supplied 15 adults of N. lugens fed on transgenic cry1C rice daily. Moist cotton was introduced into petri dish and provided as the water supply and oviposition site. Then every dish was covered with parafilm sealed edge and small hole left unsealed for breathing. Egg number of each pair was recorded daily. Ten pairs were tested for each rice line. One moist cotton was put into each well of 24-well tissue culture plate for maintaining humidity. Eggs were collected with a brush and were put individually into each well. Egg hatching was observed every day and recorded. Thirty eggs for one replicate and three replicates for each rice line.

Cry1C detection in rice plants, N. lugens and P. fuscipes

The sheaths of 15-d-old rice seedlings, nymphs of brown planthopper (first to third instar) fed on T1C-19 or Minghui 63 and newly emerged adults of P. fuscipes that preyed on first to third instar N. lugens nymphs were collected for detection of the Cry protein. For each treatment, five samples of rice sheaths (20 mg per sample), three samples of N. lugens (approximate 35 mg per sample) and three samples of P. fuscipes adults (approximate 35 mg per sample) were tested. The methods of Cry protein contents were determined by Han et al.38.

Exposure of P. fuscipes to high dose of Cry1C

Lyophilized Cry1C protein was purchased from the Biochemistry Department Laboratory, School of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, USA. The methods of purifying and lyophilizing Cry protein were described by Han et al.38.

P. fuscipes were reared on the artificial diet containing Cry1C protein. Three different dietary treatments were delivered to the first instar nymphs of P. fuscipes: (i) A pure artificial diet (negative control) and 30 (first–third instar) nymphs of N. lugens (respectively supplying 10 nymphs of N. lugens at 6, 7 and 8 d after P. fuscipes were fed artificial diets); (ii) An artificial diet containing 50 μg/g of Cry1C and 30 nymphs (first to third instar) of N. lugens (respectively supplying 10 nymphs of N. lugens at 6, 7 and 8 d after P. fuscipes were fed artificial diets); (iii) An artificial diet containing 1 mg/g of potassium arsenate (PA, positive control) and 30 nymphs (first to third instar) of N. lugens (respectively supplying 10 nymphs of N. lugens at 6, 7 and 8 d after P. fuscipes were fed). Three different diets were refreshed daily. Simultaneously, survival and molting of P. fuscipes were recorded daily. Sex and body weights of P. fuscipes were recorded when the adults were emerged. For each treatment, 75 P. fuscipes larvae were evaluated.

The artificial diet mixed with Cry1C was fed to P. interpunctella to determine Cry1C bioactivity on lepidopteran insects. Each bioassay included six concentrations of Cry1C (0, 0.02, 0.05, 0.08, 0.11 and 0.14 μg/g). For each concentration there were 40 newly hatched P. interpunctella larvae introduced on the artificial diets and 5 replicates were tested. After one week, the mortality of the larvae was recorded. The LC50 of this batch of Cry1C protein was measured.

In order to ensure the stability and the bioactivity of Cry1C protein of artificial diets that taken from the freezer and from diets that had been exposed to C. medinalis for 24 h, the Cry1C proteins were extracted from artificial diets and the methods described by Han et al.38. After 2 h of air-drying, fifteen Bt-susceptible first-instar C. medinalis were used in each treatment. And each treatment was three replicates. Mortality of the insects was calculated after 48 hours.

Data analysis

In all bioassays with P. fuscipes, statistical comparisons were made between each treatment and the control (pure diet). Student’s t-tests were used to compare the data of body weight. Mann–Whitney U-test was used to analyze the developmental time of nymphal. The parameters of preimaginal survival and female ratio were used by the Chi-square test. And the percentage data were arcsine–square root and transformed by SQRT (χ + 1) or log 10 (χ + 1). The effect of Cry1C protein dietary treatments on P. fuscipes survival was analyzed with the Kaplan-Meier procedure and log-rank test. All statistical analyses were conducted by the software package SPSS (version 16.0 for Windows, 2007).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Meng, J. et al. No impact of transgenic cry1C rice on the rove beetle Paederus fuscipes, a generalist predator of brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens. Sci. Rep. 6, 30303; doi: 10.1038/srep30303 (2016).

References

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). FAO and Sustainable Intensification of Rice Production for Food Security. ftp://ext-ftp.fao.org/ Radio/Scripts/2008/Rice- Prod.pdf (2008).

FAOSTAT. FAO Statistical databases. www.fao.org. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, Rome (2007).

Peng, S., Tang, Q. & Zou, Y. Current status and challenges of rice production in China. Plant Prod. Sci. 12, 3–8 (2009).

Lou, Y. G., Zhang, G. R., Zhang, W. Q., Hu, Y. & Zhang, J. Biological control of rice insect pests in China. Biol. Control 67, 8–20 (2013).

Chen, M., Shelton, A. & Ye, G. Y. Insect-resistant genetically modified rice in China: from research to commercialization. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 56, 81–101 (2011).

Li, Y. H., Peng, Y. F., Hallerman, E. M. & Wu, K. M. Safety management and commercial use of genetically modified crops in China. Plant Cell Rep. 33, 565–573 (2014).

Shu, Q. Y., Ye, G. Y., Cui, H. R., Xiang, Y. B. & Gao, M. W. Development of transgenic Bacillus thuringiensis rice resistant to rice stem borers and leaf folders. J. Zhejiang Agr. Univ. 24, 579–580 (1998). (In Chinese with English Abstract).

Jiao, Y. Y., Yang, Y., Meissle, M., Peng, Y. F. & Li, Y. H. Comparison of susceptibility of Chilo suppressalis and Bombyx mori to five Bacillus thuringiensis proteins. J, Invertebr. Pathol. 136, 95–99 (2016).

Azizoglu, U., Ayvaz, A., Yilmaz, S. & Temizgul, R. The synergic and antagonistic activity of Cry1Ab and Cry2Aa proteins against lepidopteran pests. J. Appl. Entomol, 140, 223–227 (2016).

Romeis, J. J. et al. Assessment of risk of insect-resistant transgenic crops to nontarget arthropods. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 203–208 (2008)

Lu, Z. X., Heong, K. L., Yu, X. P. & Hu, C. Effect of plant nitrogen on ecological fitness of the brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens, in rice. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol, 7, 97–104 (2004).

Zeng, Y. Y. et al. Effects of elevated CO2 on the nutrient compositions and enzymes activities of Nilaparvata lugens nymphs fed on rice plants. Sci. China Life Sci. 55, 920–926 (2012).

Han, Yu . et al. The influence of transgenic cry1Ab/cry1Ac, cry1C and cry2A rice on nontarget planthoppers and their main predators under field conditions. Agr. Sci. China 10, 1739–1747 (2011).

Frank, J. H. & Kanamitsu, K. Paederus, sensu lato (Coleoptera: Staphylinidae): Natural history and medical importance. J. Med. Entomol, 24, 155–191 (1987).

Luo, X. N., Zhuo, W. X. & Wang, Y. M. Preliminary study on predatory effect of Paederus fuscipes (Coleop.:Staphylinidae). Nat. Enemies Insects 11, 12–19 (In Chinese with English Abstract) (1989).

Zheng, X. S. et al. Resistance performances of transgenic Bt rice lines T-2A-1 and T1c-19 against Cnaphalocrocis medinalis (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). J. Econ. Entomol, 104, 1730–1735 (2011).

Li, Y. H., Chen, X. P., Hu, L., Romeis, J. & Peng, Y. F. Bt rice producing Cry1C protein does not have direct detrimental effects on the green lacewing Chrysoperla sinica (Tjeder). Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 33, 1391–1397 (2014).

Joern, A. & Behmer, S. T. Importance of dietary nitrogen and carbohydrates to survival, growth and reproduction in adults of the grasshopper Ageneotettix deorum (Orthoptera: Acrididae). Oecologia 112, 201–208 (1997).

Li, Y. H. et al. Consumption of Bt rice pollen containing Cry1C or Cry2A does not pose a risk to Propylea japonica (Thunberg) (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Sci. Rep. 5, 7679, 10.1038/srep07679 (2015).

Li, K. S., Chen, X. D. & Wang, H. Z. New discovery of feeding habitats of some ladybirds. Shanxi Forest Sci. Technol. 2, 84–86 (In Chinese with English Abstract) (1992).

Zhang, X. et al. Use of a pollen-based diet to expose the ladybird beetle Propylea japonica to insecticidal proteins. PLoS. ONE 9, e85395 (2014).

Lu, Z. B. et al. No direct effects of two transgenic Bt rice lines, T1C-19 and T2A-1, on the arthropod communities Environ. Entomol. 43, 1453–1463 (2014).

Bong, L. J., Neoh, K. B., Jaal, Z. & Lee, C. Y. Influence of temperature on survival and water relations of Paederus fuscipes (Coleoptera: Staphylinidae). J. Med. Entomol. 50, 1003–1013 (2013).

Bong, L. J., Neoh, K. B., Jaal, Z. & Lee, C. Y. Life table of Paederus fuscipes (Coleoptera: Staphylinidae). J. Med. Entomol. 49, 451–460 (2012).

Nasira, S., Akram, W. & Ahmed, F. The population dynamics, ecological and seasonal activity of Paederus fuscipes Curtis (Staphylinidae; Coleoptera) in the Punjab, Pakistan. APCBEE Procedia 4, 36–41 (2012).

Manley, G. V. Paederus fuscipes (Col.: Staphylinidae): a predator of rice fields in west Malaysia. Entomophga 22, 47–59 (1977).

Liu, Y. F., Zhang, G. R., Gu, D. X. & Wen, R. Z. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay used to detect the food relationships of the arthropods in paddy fields. Acta Entomol. Sin, 45, 352–358 (In Chinese with English Abstract) (2002).

Cheng, Z. X. et al. Effect of transgenic Bt rice on the survival rate and predation of Paederus fuscipes Curtis adults. Chinese J. Appl. Entomol. 51, 1184−1189 (In Chinese with English Abstract) (2014).

Balog, A., Kiss, J., Szekeres, D., Szenasi, A. & Marko, V. Rove beetle (Coleoptera: Staphylinidae) communities in transgenic Bt (MON810) and near isogenic maize. Crop. Prot. 29, 567–571 (2009).

Yu, H. L., Li, Y. H. & Wu, K. M. Risk assessment and ecological effects of transgenic Bacillus thuringiensis crops on non-target organisms. J. Integr. Plant. Biol. 53, 520–538 (2011).

Li, Y. H. et al. Development of a Tier-1 assay for assessing the toxicity of insecticidal substances against Coleomegilla maculate. Environ. Entomol, 40, 496–502 (2011).

Zhou, M. Studies on Paederus fuscipes Curtis artificial diet. Nat. Enemies Insects 28, 13–17 (In Chinese with English Abstract) (2006).

Bong, L. J., Neoh, K. B., Lee, C. Y. & Jaal, Z. Effect of Diet Quality on Survival and Reproduction of Adult Paederus fuscipes (Coleoptera: Staphylinidae). J. Med. Entomol. 51, 752– 759 (2014).

Dittman, F. & Biczkowski, M. Induction of yolk formation in hemipteran previtellogenic oocytes (Dysdercus intermedius). Invertebr. Reprod. Dev. 28, 63–70 (1995).

Wheeler, D. The role of nourishment in oogenesis. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 41, 407–431 (1996).

Davey, K. G. Hormonal controls of reproduction in female Heteroptera Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 35, 443–453 (1997).

Adams, T. S. Hematophagy and hormone release. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 92, 1–13 (1999).

Han, Y. et al. Bt rice expressing Cry2Aa does not harm Cyrtorhinus lividipennis, a main predator of the nontarget herbivore Nilapavarta lugens. PLoS ONE 9, e112315 (2014).

Chen, Y. et al. Cry1Ab rice does not impact biological characters and functional response of Cyrtorhinus lividipennis preying on Nilaparvata lugens eggs. J. Integr. Agr. 14, 2011–2018 (2015)

Han, Y. et al. Prey-mediated effects of transgenic cry2Aa rice on the spider Hylyphantes graminicola, a generalist predator of Nilapavarta lugens. BioControl 60, 251–261 (2015).

Yoshida, S., Forno, D. A., Cock, J. H. & Gomez, K. A. Laboratory manual for physical studies of rice. In: Yoshida, S., Forno, D. A., Cock, J. H. & Gomez, K. A. (Ed.), Routine procedure for growing rice plants in culture solution, Ch. 17, 61–66. 3rd Edition, International Rice Research Institute, Los Banõs, Laguna, Philippines (1976).

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Yongjun Lin (National Key Laboratory of Crop Genetic Improvement at Huazhong Agricultural University) for providing the transgenic rice seeds. This research was supported by the National Genetically Modified Organisms Breeding Major Project: Technology of Environmental Risk Assessment on Transgenic Rice (2016ZX08011-001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.X.H. designed research. J.R.M. performed the experiments. I.J., G.W. and H.X.H. wrote the manuscript. Y.N.F. raised the insects. Y.H., J.Z. and Y.P.H. analyzed the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Meng, J., Mabubu, J., Han, Y. et al. No impact of transgenic cry1C rice on the rove beetle Paederus fuscipes, a generalist predator of brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens. Sci Rep 6, 30303 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep30303

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep30303

This article is cited by

-

Emamectin benzoate induced enzymatic and transcriptional alternation in detoxification mechanism of predatory beetle Paederus fuscipes (Coleoptera: Staphylinidae) at the sublethal concentration

Ecotoxicology (2021)

-

No Effect of Bt-transgenic Rice on the Tritrophic Interaction of the Stored Rice, the Maize Weevil Sitophilus Zeamais and the Parasitoid Wasp Theocolax elegans

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Transgenic Bt rice lines producing Cry1Ac, Cry2Aa or Cry1Ca have no detrimental effects on Brown Planthopper and Pond Wolf Spider

Scientific Reports (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.