Abstract

Knowledge of population dynamics of mating types is important for better understanding pathogen’s evolutionary potential and sustainable management of natural and chemical resources such as host resistances and fungicides. In this study, 2250 Phytophthora infestans isolates sampled from 61 fields across China were assayed for spatiotemporal dynamics of mating type frequency. Self-fertile isolates dominated in ~50% of populations and all but one cropping region with an average frequency of 0.64 while no A2 isolates were detected. Analyses of 140 genotypes consisting of 82 self-fertile and 58 A1 isolates indicated that on average self-fertile isolates grew faster, demonstrated higher aggressiveness and were more tolerant to fungicides than A1 isolates; Furthermore, pattern of association between virulence complexity (defined as the number of differential cultivars on which an isolate can induce disease) and frequency was different in the two mating types. In A1 isolates, virulence complexity was negatively correlated (r = −0.515, p = 0.043) with frequency but this correlation was positive (r = 0.532, p = 0.037) in self-fertile isolates. Our results indicate a quick increase of self-fertile isolates possibly attributable to their higher fitness relative to A1 mating type counterpart in the field populations of P. infestans in China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fungal and fungus-alike pathogens such as P. infestans exhibit a wide range of reproductive systems1,2 including asexual reproduction, parasexual reproduction and sexual reproduction to transmit genetic information across generations. In heterothallic pathogens, sexual reproduction involves nuclear fusion of two distinct strains of opposite mating types, whereas homothallic pathogens are able to undergo this reproductive process within the same strains through selfing, though switches between homothallism and heterothallism have been reported in some pathogens1. The reproductive strategies adopted by plant pathogens play important roles in the evolution, epidemics and management of plant diseases through their direct or indirect impact on the generation and maintenance of genetic variation, efficiency of natural selection, extent of genetic drift3, competitive ability of immigrants and formation of spores varying in dispersal ability and stress tolerance4,5,6. For example, pathogens with a mixed reproduction system (multiple cycles of asexual multiplication mixed with fewer cycles of sexual reproduction) have a higher evolutionary potential and are more difficult to manage because this reproductive strategy allows the generation of new allelic combinations that may offer an advantage on novel hosts or in changing environments4,7, while maximizing the preservation of allelic combinations that are well adapted to existing hosts and environments.

The reproductive mode of a particular pathogen is determined not only evolutionarily by mating type genetics (e.g. heterothallism verses homothallism) but also ecologically by the spatiotemporal distribution of mating types in a population. Knowledge of mating type frequency and its spatiotemporal distribution can be used to determine the mating history of pathogen populations and is important for sustainable management of resistance genes and fungicides. In addition to their sexual function, mating type genes may contribute to other biological processes such as aggressiveness, mycelium growth and maintenance of cell wall integrity8,9,10. By combining ecological and life history trait data of pathogens (such as aggressiveness and fungicide tolerance), empirical studies of the frequency distribution of mating types may also inform their quantitative contribution to these biological processes, which usually depend on the genetic background of particular strains and are difficult to be determined by molecular analysis of individual genotypes alone.

Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) is the third-ranked food crop in total production globally11. China is the world-leading producer with annual planting areas of >5 million hectares12 and the production in the country is expected to expand in the next decades due to changes in social structure, dietary habits and governmental promotion. In China potato production occurs in four major zones: the Northern Single-crop Region (NSR), the Central Double-crop Region (CDR), the Southern Winter-crop Region (SWR) and the Southwestern Multiple-cropping Region (SMR)12, resulting in a year-round crop.

The oomycete Phytophthora infestans, the causal agent of the late blight disease of potato and tomato, is the most devastating pathogen worldwide. Annual economic losses are estimated to exceed $6.7 billion in potatoes alone in the world13. In China, the late blight disease is the main factor constraining the sustainability of potato production14, particularly in the SMR where nearly 40% of China’s potatoes are grown. In recent decades, the occurrence and severity of potato late blight in China has intensified, possibly associated with the emergence of new physiological races able to overcome the main commercial cultivars currently in use, and the invasion of a novel mating type15 that has increased the evolutionary potential of the pathogen.

P. infestans is considered to be a heterothallic organism with two mating types designated as A1 and A2, despite the existence of self-fertile isolates16. Before the 1980s, the A2 mating type was only found in Mexico. Since then it has been detected in many parts of the world including China although tremendous variation in its frequency exists geographically17,18,19. Self-fertile isolates have existed at low frequency in nature for a long time20 but recent surveys indicate that they have now emerged as a primary mating type in some parts of the world19,21,22,23. Though many previous studies of P. infestans have monitored frequency changes in mating types and from this inferred the mating system and evolutionary potential of the pathogen, few studies have been conducted to determine whether other biological causes are also driving the frequency changes. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to redress this omission by: 1) studying the spatial distribution of mating types in P. infestans populations in China; and 2) determining the mechanisms driving changes in mating type frequency by comparing their life history traits–specifically aggressiveness, in vitro growth rate and tolerance to some commercial fungicides.

Results

Distribution and homogeneity test of mating type frequency

The mating type of P. infestans isolates collected from 15 provinces in China (Table 1) was determined in vitro by pairing individual isolates with reference testers on rye B media. These assessments showed a highly skewed mating type frequency in the P. infestans populations (Table 1). Among the 2250 isolates assayed, 809 (36%) produced oospores in the presence of the A2 tester strain but not on their own and were therefore scored as A1 mating type. The remaining 1441 isolates produced oospores on their own as well as in the presence of the A1 and A2 tester strains and were scored as self-fertile mating type. No A2 isolates were detected in the samples (Table 1).

Skewed and significant differences in mating type frequency were also found when P. infestans from different provinces or cropping regions were considered separately (Table 1). Self-fertile isolates dominated the majority of P. infestans populations sampled from the NSR, SMR and SWR. All isolates from Yunnan and Ningxia were self-fertile, while no self-fertile isolates were detected in Hunan or Shanxi. The average frequency of self-fertile isolates in the populations sampled from the SMR, NSR, SWR and CDR was 92%, 62%, 53% and 17%, respectively. In contrast, the A1 mating type dominated all populations sampled from the CDR. Its frequency in the four cropping regions ranged from 8% in the SMR to 83% in the CDR.

Aggressiveness in self-fertile and A1 mating types

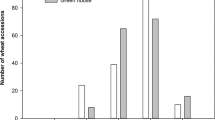

The aggressiveness of a subset of the P. infestans isolates (140 genotypes) was determined by measuring the Percentage of Leaf Area Covered by Lesions (PLACL) on a susceptible cultivar using a detached leaflet assay. PLACL of the pathogen isolates ranged from 3.52% to 99.84% with an average of 55.1% in self-fertile isolates and from 4.3% to 97.7% with an average of 51.5% in the A1 mating type (Fig. 1). Both self-fertile and A1 mating types displayed a similar unimodal distribution in aggressiveness although the distribution in the self-fertile isolates was slightly shifted towards higher aggressiveness.

Growth rate and tolerance to azoxystrobin and iprovalicarb in self-fertile and A1 mating types

Growth rates of the 140 P. infestans genotypes were determined in vitro on agar in the absence of fungicides using an exponential model based on a series of measurements of colony size over time. They ranged from 0.417 to 0.572 with an average of 0.515 cm2/day in the self-fertile mating type and ranged from 0.376 to 0.577 with an average of 0.495 cm2/day in the A1 mating type (Fig. 2). Thought both mating types displayed a similar unimodal distribution and shared a common mode, A1 isolates were slightly over represented by the slower growing phenotypes (Fig. 2). Tolerance to fungicides was determined by dividing the growth rate in the presence of azoxystrobin and iprovalicarb by that in their absence. Patterns of tolerance to different concentrations of azoxystrobin were similar for the self-fertile and A1 mating types (Fig. 3), both following a unimodal distribution. At a concentration of 0.05 μg ml−1, tolerance to azoxystrobin among the self-fertile isolates ranged from 0.599 to 1.038 with an average of 0.835 cm2/day while that for the A1 mating type isolates ranged from 0.469 to 0.981 with an average of 0.781 cm2/day (Fig. 3A). At 0.10 μg/ml, tolerance to azoxystrobin in the self-fertile isolates ranged from 0.411 to 0.853 with an average of 0.655 cm2/day while that in the A1 mating type ranged from 0.315 to 0.898 with an average of 0.629 cm2/day (Fig. 3B).

Similar to azoxystrobin, the patterns of tolerance to different concentration of iprovalicarb also displayed a unimodal distribution in both self-fertile and A1 mating types. At a concentration of 0.1 μg ml−1, tolerance to iprovalicarb in the self-fertile isolates ranged from 0.846 to 1.221 with an average of 1.030 cm2/day and that in the A1 mating type isolates ranged from 0.844 to 1.205 with an average of 1.022 cm2/day (Fig. 3C). At the concentration of 0.6 μg ml−1, tolerance to iprovalicarb in the self-fertile isolates ranged from 0.490 to 1.081 with an average of 0.866 cm2/day and that in the A1 mating type ranged from 0.531 to 1.070 with an average of 0.846 cm2/day (Fig. 3D).

Virulence complexity in self-fertile and A1 mating types

Virulence profile for each of the 140 isolates was determined on 11 differential potato cultivars each carrying one of the 11 R genes derived from Solanum demissum and one universal susceptible cultivar using a detached leaf approach. The virulence complexity of an isolate was determined by the number of differential cultivars on which the isolate could induce late blight. Virulence complexity of the 140 P. infestans genotypes evaluated ranged from 0 to 11 with an average of 6.87 in self-fertile isolates and from 0 to 9 with an average of 3.81 in A1 mating type isolates. The virulence complexity was positively correlated with the frequency of an observed self-fertile isolate, but negatively correlated with the frequency of an observed A1 mating type isolate (Fig. 4).

T-tests for difference in growth rate, aggressiveness, virulence complexity and fungicide tolerance between self-fertile and A1 mating types

There were significant differences in growth rate on rye B media, aggressiveness, virulence complexity and tolerance to azoxystrobin and iprovalicarb between self-fertile and A1 mating types (Table 2). On average, self-fertile isolates displayed higher growth rates, greater aggressiveness and higher virulence complexity than A1 mating type isolates (Table 3). Except at a lower iprovalicarb concentration (0.10 μg ml−1), self-fertile isolates on average also displayed a significantly higher fungicide tolerance than A1 isolates (Table 4).

Discussion

Substantial research has been conducted to quantify the spatiotemporal distribution of mating types in P. infestans with the ultimate goals of understanding the evolutionary potential and trajectory of the pathogen15,24,25,26 and to provide information for sustainable late blight management4,5. The outcomes of these studies and the inferences that can be made are usually tempered by the small population sizes involved. For population studies, results drawn from small sample sizes are less reliable particularly for pathogens with low genotypic variation resulting from the domination of clonal lineages such as P. infestans in China19. In this study, we used a large sample size composing of many field collections to increase the statistical confidence of our results. At the same time, the hierarchical sampling method enables us to analyze the geographical distribution of mating types over different spatial scales.

Unexpectedly, although our sampling was conducted over four years, we did not detect any A2 isolates in more than 2000 isolates of P. infestans collected across the main potato production areas of China. This result contrasts with previous reports. Though tremendous variations exist and generally lower than the frequency of A1 counterpart14,15,27, the A2 mating type has been detected in many parts of China previously. Several factors may contribute to the difference between the current and previous results. It may reflect temporal and/or spatial differences in pathogen collections, a common phenomenon in the plant pathogens which are usually characterized by meta-population structure28. Most samples with intermediate or high frequencies of A2 mating type reported previously were collected before 2010 or nursery23. In contrast, all of our isolates were collected after 2010 from commercial fields. Sample sizes and analytical approaches can have an important impact on the estimate of population genetic parameters such as mating types, particularly for pathogens dominated by asexual reproduction19. Many of previous studies used relatively small sample sizes and data were usually not clone-corrected, possibly resulting in an overrepresentation of dominant genotypes with A2 mating type such as Blue 13-A229. In the current study, sample size is large for most populations (Table 1). Though genotyping data are not available for all isolates assayed for mating types, both results from all and the 140 isolates each with different genotypes show the frequency of self-fertile mating type is ~0.60 (Tables 1 and 3). The fact that we found no A2 isolates in more than 2000 isolates suggests this mating type is now in very low frequency27 or may even have disappeared from most Chinese populations of P. infestans in recent years. It is likely that A2 mating type might have an overall lower fitness than its A1 and self-fertile counterparts (see below for the discussion of fitness differences among mating types). In a field experiment, we artificially inoculated potatoes with an equal proportion of A1 and A2 mating types each represented by three SSR-tagged genotypes. We recovered the pathogen after 8 weeks of inoculation and found that most of isolates recovered were A1 mating type (unpublished data).

Instead, a great proportion of the isolates in our collections was self-fertile with the ability to form oospores either on their own or in contact with either A1 or A2 isolates. Self-fertile isolates dominated in ~50% populations and all but one (CDR) cropping region with an overall China-wide frequency of 64%. Within individual potato growing regions the relative frequency of A1 versus self-fertile isolates in NSR and SWR showed some variation. In this respect seed potato material used in SWR typically comes from different potato breeding companies in NSR, and thus would appear to reflect the relative frequency of mating types found there.

Though we were unable to detect a directional change of frequency in the populations with multiple-year collections (data not shown), possibly due to the relatively short time interval, the finding of high frequencies of self-fertile isolates in many populations is consistent with recent reports from China19,21,23 and other parts of the world22,30 and is consistent with the rapid emergence of self-fertile isolates in the global population of P. infestans. For example, in the central highlands of Mexico, the frequency of self-fertile isolates in P. infestans populations collected between 2008 and 2010 was 76.1%30. In Gansu province of China, the frequency of self-fertile isolates in the P. infestans population increased from 0.00% in 2004 (none out of 21 isolates) to 17.6% in 2007 (15 out of 85 isolates)21. In the current study, 93% of the isolates collected from this area were classified as self-fertile (Table 1).

The skewed frequency in P. infestans mating types might be related to differences in their adaptation to biotic and abiotic environments coupled with nonrandom mating in the pathogen from this region19. Indeed, we found that on average, self-fertile isolates demonstrated higher aggressiveness (7.00%), higher fungicide tolerance (0.78–6.91%) and faster growth (4.04%) as compared to A1 isolates, suggesting a higher fitness than their counterpart. Though the differences between the two mating types in these traits are small, most of them are statistically significant (Tables 3 and 4) and could make a great contribution to the temporal population dynamics of mating frequencies. For example, assuming self-fertile mating type has 5% higher fitness than A1 mating type, its frequency would increase from 0.20 to 0.76 within 50 generations, which may only take a few years for a fast epidemic pathogen such as P. infestans. However, it should be aware that in addition to growth rate, fungicide tolerance and aggressiveness, the fitness of pathogens is also affected by many other ecological and life-history traits. Further study involved with more ecological and life-history traits is required to confirm the hypothesis of fitness difference between the two mating types.

Pleiotropic effects could be one factor causing this difference in fitness among mating types. Pleiotropy occurs when a single gene influences the expression of multiple phenotypic traits. Previous studies have demonstrated that, in addition to their primary role in determining the reproductive process, mating type genes are also associated with other biological functions such as maintenance of cell wall integrity31, aggressiveness32 and hyphal formation10. Genetic variation is low in these populations of P. infestans. Linkage disequilibrium could be another factor responsible for the observed differences in fitness among the two mating types. Only ~3 alleles were detected at each locus and many P. infestans genotypes in the current study varied by only 1–2 alleles across eight SSR loci assayed33, suggesting they have probably descended through mutation from just a few genetic backgrounds. Possibly, the self-fertile isolates are strongly linked with clones of a higher fitness. If this is the case then the increased frequency in self-fertile isolates may be due to hitchhiking selection34 for fitter genetic backgrounds.

The most interesting result in the current study is found in the association analysis showing different patterns of correlation between virulence complexity and frequency distribution in self-fertile and A1 mating types. We detected a negative correlation between the virulence complexity and frequency in the A1 mating type, consistent with the hypothesis of the existence of a fitness cost for pathogens carrying more virulence factors26,35. However, the correlation between the virulence complexity and frequency in the self-fertile isolates is positive. This result is unexpected and suggests a better performance of more complex pathogen races with a self-fertile background. Though the evolutionary mechanisms accounting for the better performance for greater virulence complexity in self-fertile isolates of P. infestans are not clear, the phenomenon of gradual increase in virulence complexity has also been reported in other pathogens including Rhynchosporium secalis36, Erysiphe fischeri37 and Melampsora lini38 though it is not clear whether the dynamic pattern of virulence complexity in these pathogens is mating type dependent as documented in the current study. While it has been demonstrated that many agricultural practices, such as the extensive use of R gene pyramids, cultivar mixtures, or breeding materials from composite crosses can cause selection favoring complex races36, these practices do not exist in potato cultivation in China. In this country, the late blight is primarily controlled by spraying fungicides or using quantitative and/or simple R genes from S. demissum.

Though marginally, significantly faster growth, higher aggressiveness and greater tolerance to antimicrobials in self-fertile isolates comparable to their A1 counterparts, coupled with the positive association between virulence complexity and self-fertile frequency, may have many practical implications for sustainable potato late blight control in agro-ecosystems. It suggests that genotypes with enhanced aggressiveness and resistance to antimicrobials could be generated by mutation, occasional sexual reproduction or other mechanisms and selected for under continuous and widespread use of the same resistant cultivars or antimicrobials. In this case, dynamic disease management strategies4,5 such as crop rotation, R-gene rotation, R-gene rotation combined with pyramiding should be utilized to promote diversifying selection.

Materials and Methods

Phytophthora infestans collection

Pathogen isolates were collected from 61 fields located in 15 provinces across the four major potato production zones of China between 2010 and 2013 (Table 1). For all collections, infected leaves were sampled at more than 2 m intervals from different parts of a field with at least 30 infected leaves being collected from each field. Each infected leaf was packed in a separate sandwich bag and sent to the laboratory for isolation where a single pathogen strain was isolated from each leaf. Single-spore isolates were maintained as axenic cultures on rye B agar as described previously19. All isolates were tested for mating types (see next section). A sub-set of isolates was genotyped with eight SSR markers as described previously33 and 140 isolates each with a different molecular profile33 were randomly selected for biological assays of growth rate, aggressiveness, virulence complexity and fungicide sensitivity as described below. The details for pathogen isolation and molecular characterizations of these populations can be found in our previous publications19,33,39.

Mating type test

Mating type was determined in vitro as described previously27. Briefly, each P. infestans isolate was paired with an A1 tester (US970001), an A2 (US940480) or grown alone on rye B agar plates supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg ml−1) and rifampin (10 μg ml−1). After inoculation, agar plates were held at 18 °C in the dark for 12–15 days. When colonies from testers and tested isolates met, a piece of tissue was cut from the intersecting edge of the two colonies and observed microscopically to determine the production of oospores. Isolates forming oospores with the A2 tester were designated as A1 mating type. Similarly, isolates forming oospores when paired with the A1 tester were designated as A2 mating type. Isolates forming oospores with both testers and on their own were designated as self-fertile. Mating type determination was replicated three times for each isolate.

Aggressiveness test

Aggressiveness was tested on the potato cultivar Bintje, a cultivar susceptible to all known races of P. infestans, using a detached leaflet assay40. In this assay each isolate was cultured on a rye B agar plate at 18 °C in the dark. Sporangia were harvested after 14 days by scraping the culture with a glass rod after flooding the plates with ~2 ml of chilled sterile distilled water. Sporangial suspensions were adjusted to a concentration of 5 × 104 sporangia ml−1 using a Fuchs-Rosenthal haemocytometer and kept at 4 °C for 3–4 hours to promote zoospore release before inoculation. Fully expanded leaflets excised from Bintje plants grown in a glasshouse for 8 weeks were drop-inoculated with 5 μl of the calibrated sporangial suspensions and kept on 2% water-agar plates at 18 °C in an incubator supplemented with 16 h light daily. Diseased leaves were digitized seven days post inoculation and the area occupied by lesions was measured electronically with the image analysis software Assess41. Aggressiveness tests were repeated five times for each isolate.

Virulence test

Virulence was tested by the detached leaf assayed as described previously26. Specifically, virulence was evaluated by inoculating spores of isolates individually onto 11 differential potato cultivars each expressing one of the R1-R11 known R genes from Solanum demissum42 and one universal susceptible cultivar (Bintje) using the same inoculum volume and concentrations and post-inoculation incubation conditions as described above for the aggressiveness test. Infection types were recorded seven days after inoculation and the test was replicated five times for each pair of isolate-differential interaction.

Fungicide tolerance

P. infestans isolates from long-term storage were revived on rye B agar at 18 °C for 10 days. Mycelial plugs (10 mm in diameter) were taken from the margin of revived colonies and inoculated onto new rye B plates supplemented with either azoxystrobin (Sigma, Aldrich), iprovalicarb (Sigma, Aldrich) or without the fungicides (controls). Azoxystrobin concentrations used in the experiment were 0.05 and 0.10 μg ml−1 while those for iprovalicarb were 0.1 and 0.6 μg ml−1. Preliminary experiments indicated that these doses yielded the best result in differentiating azoxystrobin or iprovalicarb sensitivity among isolates. Many isolates did not grow when a higher dose was used while growth rates in many isolates were not significantly changed at a lower dose. The inoculated plates were kept at 18 °C in the dark and resulted colonies were photographed in 3, 5, 7, 8 and 9 days after inoculation. Colony sizes were measured using the image analysis software Assess. All treatments including controls were replicated three times. More details for the fungicide tolerance test were described previously33.

Data analyses

To increase statistical power, isolates from different fields of the same province were pooled together to form a larger population. Mating type frequency was tabulated according to their geographic locations and its heterogeneity within cropping regions was evaluated with a contingency χ2 test43. Growth rates of the isolates in fungicide treatments and controls were estimated using an exponential model based on the sizes (areas) of individual colonies quantified at each point in time over the experiment. Tolerance to azoxystrobin and iprovalicarb was rated by dividing the growth rate in the presence of fungicides by that in the absence of the two fungicides as described previously44. Aggressiveness was measured as the percentage of leaf area covered by lesions (PLACL)45. Aggressiveness, growth rate and fungicide tolerance in each of the mating type categories (A1 and self-fertile) were grouped using a binning approach commonly used to display the percentile of continuous data46,47 in biological and other studies and frequency distributions were labeled graphically with the mid-point value of the lower and upper boundaries of the corresponding bins48. To construct the histograms, data are split into bins with each bin representing an interval of continuous data starting from the smallest bin. Each bin contains the number of occurrences in the data set that are within the corresponding bin. For example, to construct the histogram of growth rate (Fig. 1), data were split into six bins with each bin representing a 0.05 interval starting from 0.40.

Virulence profiles with respect to the 11 differentials and the universally susceptible cultivar were used to determine the race type of the isolate. An isolate was considered to carry a virulence factor towards a particular R gene (differential cultivar) if it induced a late blight lesion. The virulence complexity of an isolate was determined according to the number of differential cultivars on which the isolate induced disease36. A complexity index of “11” indicates that the isolate can infect all 11 differential cultivars while a complexity index of “0” indicates that the isolate is able to induce late blight disease on the universally susceptible cultivar only. All isolates carrying the same number of virulence factors were treated as having the same virulence complexity regardless of the combination of differential cultivars to which they showed virulence36.

Analysis of variance on growth rate, aggressiveness, virulence complexity and fungicide tolerance was performed using the general linear model procedure implemented in SAS 6.03 (SAS Institute) by treating “mating type as a fixed effect and “isolate” as a random effect and PLACL data were square root transformed. T-test46 was used to compare growth rate, aggressiveness, virulence complexity and fungicide tolerance between mating type groups and Pearson correlation49 was used to evaluate the association between virulence complexity and its observed frequency in each of the mating type groups.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Zhu, W. et al. Increased frequency of self-fertile isolates in Phytophthora infestans may attribute to their higher fitness relative to the A1 isolates. Sci. Rep. 6, 29428; doi: 10.1038/srep29428 (2016).

References

Billiard, S. et al. Having sex, yes, but with whom? Inferences from fungi on the evolution of anisogamy and mating types. Biol. Rev. 86, 421–442 (2011).

Lee, S. C., Ni, M., Li, W. J., Shertz, C. & Heitman, J. The evolution of sex: a perspective from the fungal kingdom. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 74, 298–340 (2010).

Stefansson, T. S., McDonald, B. A. & Willi, Y. The influence of genetic drift and selection on quantitative traits in a plant pathogenic fungus. PloS One 9, e0112523 (2014).

Zhan, J., Thrall, P. H., Papaix, J., Xie, L. & Burdon, J. J. Playing on a pathogen’s weakness: using evolution to guide sustainable plant disease control strategies. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 53, 19–43 (2015).

Zhan, J., Thrall, P. H. & Burdon, J. J. Achieving sustainable plant disease management through evolutionary principles. Trends Plant Sci. 19, 570–575 (2014).

Zhan, J. & McDonald, B. A. Experimental measures of pathogen competition and relative fitness. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 51, 131–153 (2013).

McDonald, B. A. & Linde, C. Pathogen population genetics, evolutionary potential, and durable resistance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 40, 349–379 (2002).

Lockhart, S. R., Wu, W., Radke, J. B., Zhao, R. & Soll, D. R. Increased virulence and competitive advantage of a/α over a/a or α/α offspring conserves the mating system of Candida albicans . Genetics 169, 1883–1890 (2005).

Irzykowska, L. et al. Association of mating-type with mycelium growth rate and genetic variability of Fusarium culmorum. Central Euro . J. Biol. 8, 701–711 (2013).

Barbour, L. & Xiao, W. Mating type regulation of cellular tolerance to DNA damage is specific to the DNA post-replication repair and mutagenesis pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 59, 637–650 (2005).

Birch, P. R. et al. Crops that feed the world 8: Potato: are the trends of increased global production sustainable? Food Secur. 4, 477–508 (2012).

Wang, B. et al. Potato viruses in China. Crop Prot. 30, 1117–1123 (2011).

Haverkort, A. J. et al. Societal costs of late blight in potato and prospects of durable resistance through cisgenic modification. Potato Res. 51, 47–57 (2008).

Li, Y. et al. Population structure of Phytophthora infestans in China-geographic clusters and presence of the EU genotype Blue_13. Plant Pathol. 62, 932–942 (2013).

Guo, L., Zhu, X. Q., Hu, C. H. & Ristaino, J. B. Genetic structure of Phytophthora infestans populations in China indicates multiple migration events. Phytopathology 100, 997–1006 (2010).

Judelson, H. S. Expression and inheritance of sexual preference and selfing potential in Phytophthora infestans . Fungal Genet. Biol. 21, 188–197 (1997).

Flier, W. G. et al. Genetic structure and pathogenicity of populations of Phytophthora infestans from organic potato crops in France, Norway, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. Plant Pathol. 56, 562–572 (2007).

Danies, G. et al. An ephemeral sexual population of Phytophthora infestans in the northeastern United States and Canada. PloS One 9, e0116354 (2014).

Zhu, W. et al. Limited sexual reproduction and quick turnover in the population genetic structure of Phytophthora infestans in Fujian, China. Sci. Rep. 5, srep10094 (2015).

Tantius, P. H., Fyfe, A. M., Shaw, D. S. & Shattock, R. C. Occurence of the A2 mating type and self-fertile isolates of Phytophthora infestans in England and Wales. Plant Pathol. 35, 578–581 (1986).

Han, M. et al. Phytophthora infestans field isolates from Gansu province, China are genetically highly diverse and show a high frequency of self fertility. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 60, 79–88 (2013).

Lehtinen, A. et al. Phenotypic variation in Nordic populations of Phytophthora infestans in 2003. Plant Pathol. 57, 227–234 (2008).

Tian, Y. et al. Population structure of the late blight pathogen Phytophthora infestans in a potato germplasm nursery in two consecutive years. Phytopathology 105, 771–777 (2015).

Yoshida, K. et al. The rise and fall of the Phytophthora infestans lineage that triggered the Irish potato famine. Elife 2, 00731 (2013).

Hwang, Y. T. et al. Evolution and management of the Irish potato famine pathogen Phytophthora infestans in Canada and the United States. Am. J. Potato Res. 91, 579–593 (2014).

Montarry, J. et al. Microsatellite markers reveal two admixed genetic groups and an ongoing displacement within the French population of the invasive plant pathogen Phytophthora infestans . Mol. Ecol. 19, 1965–1977 (2010).

Li, B. et al. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of Phytophthora infestans isolates from China. J. Phytopathol. 157, 558–567 (2009).

Burdon, J. J. & Thrall, P. H. What have we learned from studies of wild plant-pathogen associations?– the dynamic interplay of time, space and life-history. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 138, 417–429 (2014).

Cooke, L. R. et al. The Northern Ireland Phytophthora infestans population 1998-2002 characterized by genotypic and phenotypic markers. Plant Pathol. 55, 320–330 (2019).

Alarcon-Rodriguez, N. M., Lozoya-Saldana, H., Valadez-Moctezuma, E., Garcia-Mateos, M. D. & Colinas-Leon, M. T. Genetic diversity of potato late blight [Phytophthora infestans (Mont) de Bary] at Chapingo, Mexico. Agrociencia 47, 593–607 (2013).

Verna, J. & Ballester, R. A novel role for the mating type (MAT) locus in the maintenance of cell wall integrity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Mol. Gen. Genet. 261, 681–689 (1999).

Zhan, J., Torriani, S. F. F. & McDonald, B. A. Significant difference in pathogenicity between MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 isolates in the wheat pathogen Mycosphaerella graminicola . Fungal Genet. Biol. 44, 339–346 (2007).

Qin, C. F. et al. Comparative analyses of fungicide sensitivity and SSR marker variations indicate a low risk of developing azoxystrobin resistance in Phytophthora infestans. Sci. Rep. 6, srep20483 (2016).

Fay, J. C. & Wu, C. I. Hitchhiking under positive Darwinian selection. Genetics 155, 1405–1413 (2000).

Leach, J. E., Vera Cruz, C. M., Bai, J. & Leung, H. Pathogen fitness penalty as a predictor of durability of disease resistance genes. Annu. Rev. phytopathol. 39, 187–224 (2001).

Zhan, J., Yang, L., Zhu, W., Shang, L. & Newton, A. C. Pathogen populations evolve to greater race complexity in agricultural systems-evidence from analysis of Rhynchosporium secalis virulence data. PloS One 7, e0038611 (2012).

Bevan, J. R., Crute, I. R. & Clarke, D. D. Variation for virulence in Erysiphe fischeri from Senecio vulgaris . Plant Pathol. 42, 622–635 (1993).

Thrall, P. H. & Burdon, J. J. Evolution of virulence in a plant host-pathogen metapopulation. Science 299, 1735–1737 (2003).

Fang, Z. G. Mating type and avirulence gene diversity of Phytophthora infestans in China. MSc thesis, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University (2013).

Zhu, S. et al. An updated conventional- and a novel GM potato late blight R gene differential set for virulence monitoring of Phytophthora infestans . Euphytica 202, 219–234 (2015).

Lamari, L. Assess: Image analysis software for plant disease quantification. (APS Press, St. Paul, MN., 2002).

Black, W., Mastenbroek, C., Mills, W. R. & Peterson, L. C. A proposal for an international nomenclature of races of Phytophthora infestans and of genes controlling immunity in Solanum demissum derivates. Euphytica 2, 173–179 (1953).

Everitt, B. S. The analysis of contingency tables. 1–37 (CRC Press, Florida, 1992).

Zhan, J., Stefanato, F. L. & McDonald, B. A. Selection for increased cyproconazole tolerance in Mycosphaerella graminicola through local adaptation and in response to host resistance. Mol. Plant Pathol. 7, 259–268 (2006).

Zhan, J. et al. Variation for neutral markers is correlated with variation for quantitative traits in the plant pathogenic fungus Mycosphaerella graminicola . Mol. Ecol. 14, 2683–2693 (2005).

Yang, L., Gao, F., Shang, L., Zhan, J. & McDonald, B. A. Association between virulence and triazole tolerance in the phytopathogenic fungus Mycosphaerella graminicola . PloS One 8, e0059568 (2013).

Ott, R. L. & Longnecker, M. T. An introduction to statistical methods and data analysis. 1–1273 (Duxbury Press, Belmont, 2008).

Zhan, J. & McDonald, B. A. Thermal adaptation in the fungal pathogen Mycosphaerella graminicola . Mol. Ecol. 20, 1689–1701 (2011).

Lin, L. I. A concordance correlation coefficient to evaluate reproducibility. Biometrics 45, 255–268 (1989).

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Qinghe Chen of the Fujian Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Fuzhou, China for providing two mating type testers for the experiment. This work was supported by China Agriculture Research System (CARS-10), Fujian Technology Plan project (2012N4001), the National Science Foundation of Fujian Province of China (2016J01111), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31371901), the Ministry of Science and Technology of China “973” Initiative grant (2014CB160315) and the Ministry of Agriculture Special Fund for Agro-scientific Research in the Public Interest (201303018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.Z. and L.-L.S. collected the pathogen isolates, generated and analyzed the data and wrote the paper; Z.-G.F., L.-N.Y., J.-F.Z. and D.-L.S. collected pathogen isolates and generated the data; J.Z. conceived and designed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, W., Shen, LL., Fang, ZG. et al. Increased frequency of self-fertile isolates in Phytophthora infestans may attribute to their higher fitness relative to the A1 isolates. Sci Rep 6, 29428 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29428

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29428

This article is cited by

-

First report of molecular identification of Phytophthora infestans causing potato late blight in Yemen

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Characterization of mating type and the diversity of pathotypes of Phytophthora infestans isolates from Southern Brazil

Journal of Plant Diseases and Protection (2020)

-

Enhanced agricultural sustainability through within-species diversification

Nature Sustainability (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.