Abstract

Freshwater peatlands are carbon accumulating ecosystems where primary production exceeds organic matter decomposition rates in the soil, and therefore perform an important sink function in global carbon cycling. Typical peatland plant and microbial communities are adapted to the waterlogged, often acidic and low nutrient conditions that characterise them. Peatlands in coastal locations receive inputs of oceanic base cations that shift conditions from the environmental optimum of these communities altering the carbon balance. Blanket bogs are one such type of peatlands occurring in hyperoceanic regions. Using a blanket bog to coastal marsh transect in Northwest Scotland we assess the impacts of salt intrusion on carbon accumulation rates. A threshold concentration of salt input, caused by inundation, exists corresponding to rapid acidophilic to halophilic plant community change and a carbon accumulation decline. For the first time, we map areas of blanket bog vulnerable to sea-level rise, estimating that this equates to ~7.4% of the total extent and a 0.22 Tg yr−1 carbon sink. Globally, tropical peatlands face the proportionally greatest risk with ~61,000 km2 (~16.6% of total) lying ≤5 m elevation. In total an estimated 20.2 ± 2.5 GtC is stored in peatlands ≤5 m above sea level, which are potentially vulnerable to inundation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Peatland ecosystems play an important role in the global carbon cycle1,2,3, containing around 600 Gt of carbon sequestered persistently since the Last Glacial Maximum4. They are also biodiverse and help support the livelihoods of communities worldwide5. Accumulation of carbon-rich peat deposits occurs when net primary production (NPP) exceeds the rate of decomposition in the peat matrix, which is supressed by anoxic and often acidic conditions6. Whilst definitions vary contextually7, peatlands can be geographically categorised as either tropical (occurring between 30°S–30°N) or high-latitude (boreal and temperate regions). High latitude peatlands are more extensive; they represent 90% of the total peatland area and contain 562 Gt of carbon compared to 50 Gt in tropical peatlands2.

The continuing existence of peatland ecosystems is endangered by climate change and direct anthropogenic pressures (e.g. drainage, pollution and extraction). Rising global sea levels are also a possible threat8,9 and may drive future releases of stored carbon10,11. Between 1901–2010 global average sea level rose by 0.19 ± 0.02 m12. Projections of 21st century global mean sea level show continuing rise at rates exceeding the observed 1971–2010 average (2.0 ± 0.3 mm yr−1) at all representative concentration pathway scenarios13. As sea levels rise, the frequency and magnitude of salt-transfer to peatlands will increase, threatening those at very low elevation. Palaeoenvironmental evidence indicates that freshwater peatlands have undergone similar changes in the past with records of both marine transgressions under rising Holocene sea levels14, as well as coastward colonisation in areas of relative sea-level fall15.

Blanket bogs are distinctive ecosystems occupying the coastal niches (hyperoceanic regions) of the high-latitude peatland space, which makes them especially vulnerable to sea-level change. Their occurrence in such regions is driven by unique climatic requirements of high year-round rainfall and low summer temperatures16. Sphagnum mosses have low salt tolerance and typically dominate understorey vegetation assemblages. They are important in the accumulation of carbon and thought to hold more organic C than any other plant genus6. As for all peatlands, viable long-term persistence of blanket bog is dependent on the maintenance of a positive carbon balance, i.e. draw-down of atmospheric carbon must exceed the quantity lost through numerous export pathways17. Despite the occurrence of blanket bogs within coastal interface zones, the potential for enhanced oceanic salt inputs to perturb these ecosystems and their carbon balance remains understudied. Indeed no estimates for the areal extent of threatened blanket bog currently exist.

Previous observational studies on the ecological impact of oceanic salinity on peatlands have focused on the lithotrophic-thalassotrophic gradient, encompassing responses to variable deposition of oceanic ions (S2−, Cl−, Mg2+, etc.) at the landscape scale7,18,19. Specifically we investigate, at the local-scale, the impacts of direct salt-water delivery from the ocean to blanket bogs via inundation. We interpret a modern blanket bog salinity gradient as a spatial analogue for the ecosystem response to increased salt inputs in order to forecast the potential effects of future inundation on the ecosystem and carbon balance. We combine this empirical approach with mapping of peatland areas at risk globally in order to consider the future longevity of coastal blanket bogs and their associated carbon sink function.

Study Area

The blanket bog to coastal marsh transition at Kentra Bay, Northwest Scotland (56°45′N, 5°50′W) (Fig. 1; Supplementary material 1) provides several advantages for studying the impact of salinity on the ecosystem and carbon accumulation. The meso-tidal regime of the bay and its high salinity (33%20) waters produce a measurable salinity gradient across the coastal interface. The bay is also sheltered from high-energy waves protecting the blanket bog from erosion and allowing it to exist close to sea level. Additionally, the site permits establishment of a continuous transect focused on a small region with minimal macro-topographic variability thereby controlling against climatic effects on peat development.

(a) Arrangement of the transect belt, and location of cores, divided into three sections based on vegetation. Section A (C1–C4: Red) inundated regularly, Section B (C5–C10: Blue), and Section C (C11–C13: Grey). Filled markers indicate cores used to calculate carbon accumulation and assess peat properties. Hollow markers indicate cores used to assess peat properties only. Spot height markers indicate elevation above sea level. (b) Location of the site at Kentra Bay and Moss, Northwest Scotland within the United Kingdom. Produced using ESRI ArcMap 10.1. (http://www.esri.com/). Contains OS data © Crown copyright (2015).

Peat initiation at the site occurred approximately 8,000 years before present (8 kyr B.P.), within topographic surface depressions of a fluvioglacial outwash fan deposited during the Loch Lomond stadial (11–10 kyr B.P.)21,22. Blanket bog, which now covers the site, expanded continually toward the coast to its present limit as sea levels fell throughout the Holocene23. The bog surface has a well-developed patterning of elongate surface pools and ridges aligned with contours of the underlying outwash fan which drop gently towards the coast21,22, where a narrow strip of salt marsh has established.

Vegetation is characteristic of western blanket bog22, with abundant Sphagnum spp. and distinctive Racomitrium lanuginosum hummocks. Summer water surplus is 500 mm22 with an average yearly total of ~1700 mm distributed evenly24. Rainfall of more than 1 mm occurs on average 192 days per year; mean annual temperature is 7.9 °C, and mean temperature of the warmest month is 13.6 °C24. The site has not been substantially altered by anthropogenic activity, although some peat extraction has occurred in peripheral areas and a road runs across the site. The transect we studied represents a rare uninterrupted succession from salt marsh to ombrotrophic bog habitat, and therefore provides a unique opportunity to directly assess the impacts of salt-flux.

Results

Surface Water Salinity Gradient

Conductivity and pH measurements of surface waters identify a gradient of oceanic base cations along the transect belt at Kentra Bay (Supplementary material 2), which we separate into three sections (A–C) according to dominant vegetation to assess the effect of salinity on: peat properties (Fig. 2) and carbon accumulation rates. High pH and conductivity values between 0–200 m from the coast are due to salt input from either tidal inundation or less frequent storm surges. During high tides salt water infiltrates inland via a dendritic system of channels which drain from the bog at low tide (Section A, salt marsh). Beyond 200 m inland, above the maximum inundation level, a rapid transition to predominantly ombrotrophic conditions occurs (i.e. low conductivity and low pH). Here, limited salt deposition from; sea-spray during storms, fog and precipitation, nourishes the ecosystem due to its close coastal proximity (Section B, coastal bog). At the distal end of the transect (2 km inland, Section C, blanket bog) true ombrotrophic conditions prevail, due to isolation from the coast, although precipitation and fog deposition of salt enhance inputs relative to blanket bog in more isolated upland areas.

Sections A–C correspond to Fig.1 and are divided by dominant vegetation to aid interpretation. Dominant species are; Armeria maritima and Plantago spp. (Section A), Ericaceae, Eriophorum spp. and Molinia caerulea (Section B) and, Racomitrium lanuginosum and Sphagnum spp. (Section C). Vegetation type, refers to percentage surface cover of Sphagnum spp. (black), other bryophytes (dark-grey) and vascular plants (light-grey). Red triangles indicate the positions within the transect of cores analysed for carbon accumulation rate (Fig. 3).

Peat Properties

The thirteen monolith-cores analysed (C1–C13, Fig. 1) provide an insight into patterns of variability in peat composition across the blanket bog to coast interface. Peat formed at the coast (Section A), displays the highest average bulk density and lowest carbon content relative to peat formed where inundation does not occur (Table 1). Down-core variability in bulk density is more pronounced in the inundated peat, and cores taken inland where peat was composed mostly of decaying Sphagnum tissue show only minor variability of bulk density with depth. Maximum average carbon content is 51.47% (C9, Section B) and the lowest is 19.19% (C1, Section A).

We use ash-free bulk density (Fig. 2) as a proxy for level of decomposition25,26. Results indicate that organic matter comprising peat in areas closer to the coast (Section A and B) is generally more decomposed than those isolated from the coast (Section C).

Average moisture content within each core mirrors the gradient of salinity across the site – characterised by an abrupt change from low to high moisture conditions at 200 m from the coast, where water chemistry measurements indicate the transition to ombrotrophic conditions.

Vegetation

Considerable variation of the blanket bog surface was observed along the gradient of salinity (Fig. 2; Supplementary material 3). Frequently inundated areas (Section A) are characterised by a low diversity of small stature halophilic plant species (e.g. Armeria maritima, Glaux maritima, Plantago maritima and Salicornia maritima). Above the inundation level (Section B), vegetation changed rapidly from halophilic to acidophilic species. Here plant stature and diversity increases, with a dense canopy including Agrostis capillaris, Molinia caerulea and woody species (e.g. Calluna vulgaris and Erica tetralix). Sphagnum mosses and other bryophytes (notably Racomitrium lanuginosum as the main hummock species) dominate within Section C, accompanied by species adapted to blanket bog conditions including Narthecium ossifragum, Drosera intermedia as well as Myrica gale. At the distal end of the transect (2,000 m inland), where a complex system of pools have developed, species such as Menyanthes trifoliata are present.

We interpret canopy height as an indicator of NPP, with greater canopy height indicating higher productivity27. Canopy height is very low at the coast, peaks at ~500 m inland, before declining further inland (Fig. 2). Average canopy height also indicates the type of vegetation colonising the bog surface, since bryophytes are slow growing and of small stature compared with vascular plants. The dominance of slow growing bryophytes (including Sphagnum spp.) within Section C results in lesser input of organic carbon to the soil, whereas enhanced inputs occur where faster growing vascular species predominate.

The zonation of Sphagnum spp. along the transect coincides with surface water chemistry variation, with low pH values and conductivity corresponding to areas of Sphagnum spp. presence. Areas where Sphagnum spp. are present are also characterised by high soil moisture contents. Sphagnum spp. are absent between 0–200 m from the coast, with the exception of isolated areas where topography prevents inundation.

Carbon Accumulation

Integration of carbon density and age-depth models from spheroidal carbonaceous particles (SCP) and 210Pb dating provides the rate and total carbon accumulation since 1900. Carbon accumulation results plotted against elevation allow direct assessment of the impact of inundation (Fig. 3). Greatest accumulation since 1900 (8,260 ± 730 gCm−2) was recorded within Section B at 5.4 m above sea level, where low-concentration salt input and no inundation occurs. Carbon accumulation where salt water inundation occurs regularly is substantially lower (4,135 ± 620 gCm−2). From 2–6 m above sea level (~0–500 m inland) total carbon accumulated since 1900 increases abruptly. Greatest peat depth occurs in Section C (Fig. 2) and generally declines toward the coast.

Sections of variable salt input (A–C) correspond with Figs 1 and 2. Dark red indicates the maximum level of tidal inundation. Filled markers represent carbon accumulation calculated using 210Pb dating whilst hollow markers indicate results derived from Spheroidal Carbonaceous Particle dating. Error bars show uncertainty associated with sampling and dating accuracy.

The individual datasets were brought together using a stepwise multivariate regression to understand whether total carbon accumulation since 1900 can be predicted from any of the measured variables. Conductivity first and then elevation were found to be the two statistically significant predictor variables. Conductivity presents a negative linear relationship to carbon accumulation since 1900 (p = 0.0057), while elevation presents a quadratic relationship with accumulation (Fig. 3). Overall the model fit was high (Adjusted R2 = 0.76) and also significant (F(2, 5) = 12.13, p = 0.012), suggesting that increases of salinity are likely to result in lower accumulation. Elevation is less significant (p = 0.013), but also exerts some control over the total carbon accumulated since 1900. The maximum accumulation values occur at mid elevation and we discuss the possible implications of this in the discussion section.

Mapping low elevation peatlands

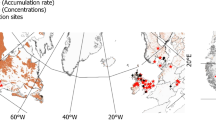

Global assessment of peatland areas vulnerable to sea-level rise revealed a disjunctive pattern (Fig. 4). Our analysis indicates that ca. 145,000 km2 of peatlands are located at or below 5 m elevation, in close agreement with an earlier estimate10.

Insets (A–E) show the locations of low lying blanket bog areas (red shading). Produced using ESRI ArcMap 10.2. (http://www.esri.com/).

Because blanket bogs are constrained climatically to hyperoceanic regions at high-latitude16, our mapping indicates that vulnerable areas occur within all of the major regions in which they are present. In South America, potentially threatened areas exist in western Patagonia and the Falkland Islands; in North America, on the coast of British Columbia and substantial areas in Newfoundland; and in Europe within Scotland, Iceland and Ireland. Vulnerable areas also exist around the coast of Kamchatka in Russia. According to our mapping, blanket bogs cover a total land area of 155,000 km2 of which ~7.4% is below 5 m elevation, equating to approximately 11,500 km2 of blanket bogs at risk.

The spatial investigation of regions at risk identified that approximately 16.6% of tropical peatlands (30°N–30°S of the equator) are situated at or below 5 m elevation and can therefore be considered vulnerable to future sea-level changes (Table 2). This equates to ca. 61,000 km2 and a store of 8.28 ± 1.0 Gt of carbon2. High latitude peatlands are proportionately less vulnerable by percentage with approximately 2% at or below 5 m. However, because the majority of peatlands occur at high latitude this equates to ~83,000 km2 and 12 ± 1.7 Gt of carbon2.

Discussion

Hyperoceanic conditions and the influence of the Gulf Stream provide suitable bioclimatic space for blanket bog development at Kentra Moss, and therefore landscape-scale proximity to the Atlantic Ocean is an important influence on ecosystem functioning and carbon sequestration at the site. The focus of our work has been to investigate the impact of high concentration oceanic salt input on coastal blanket bogs at the sub-kilometre scale.

We attribute the conductivity gradient to the morphology of the site, because it allows oceanic salt deposition from both direct (inundation) and atmospheric (salt-spray, fog and precipitation) sources. When combined, these delivery mechanisms produce the salinity gradient, which we classified into three sections; (A) land inundated directly, (B) areas not inundated but receiving enhanced atmospheric salt input owing to coastal proximity, and (C) inland areas receiving lower concentrations due to increased isolation from the coast. Indeed, surface water pH across Kentra Moss (mean = pH 4.82) is higher than expected (<4) for ombrotrophic blanket bog9,28, indicative of continual oceanic base cation input. Similarly elevated pH values have been reported for coastal blanket bogs nearby in the North of Scotland29 and West Coast of Ireland14.

Surface water conductivity (a proxy for salinity) was identified as the most powerful explanatory variable in predicting carbon accumulation at Kentra Moss, indicating that oceanic salt input exerts control on blanket bog ecosystem functioning. Since carbon accumulation rates reflect the balance of carbon inputs and outputs, the effects of salt on both the ecosystem NPP and decomposition processes are needed to explain our results.

Sphagnum mosses actively create conditions of acidity, low-nutrients and soil anoxia, allowing them to outcompete vascular plants30. Such conditions were found in areas of lower salt input where Sphagnum spp. dominate (Section C). Importantly for carbon accumulation, the release of phenolic compounds from Sphagnum inhibit microbial decomposition31 and recalcitrant tissue slows the decay of its biomass relative to that of vascular plants30, facilitating the net accumulation of carbon. Whilst Sphagnum biomass is generally not the largest component of input NPP32, a greater percentage of its biomass resists decay in the surface aerobic acrotelm and is transmitted to long-term storage in the anaerobic catotelm. The expansion of Sphagnum spp. coastward at Kentra is constrained by high-concentration salt input from inundation, supporting recent work suggesting their low tolerance to salinity33.

Mineral enrichment from atmospheric salt delivery in intermediate areas (Section B) moderate the low nutrient and acidic conditions, favouring the more productive (and faster decomposing) vascular plants which outcompete Sphagnum spp. to colonise the surface. This effect on ecosystem functioning can be considered analogous to the impacts of Nitrogen deposition from industrial and agricultural pollution. Similarly, Nitrogen deposition also leads to vascular plant dominance34 and to a shift in the decomposition pathway from methane to nitrate or sulphate as the final electron acceptor35. We therefore expect higher decomposition rates in areas of strong salt influence, and this is corroborated by our ash-free bulk density measurements, which are lowest inland.

Decomposition processes are also strongly affected by the position of the water table. Lower soil moisture content at the coast represents the hydrological connectivity between tidal and water-table fluctuation within this section of the transect. At low tide the water-table drops switching decomposition of organic matter from the slower anaerobic to the faster aerobic pathway, increasing microbial respiration of input biomass and reducing carbon accumulation. Furthermore, there may be an unquantified amount of carbon loss via particulate organic carbon (POC) and dissolved organic carbon (DOC) transportation during the downward tidal water movement. Through ombrotrophication (blanket bog expansion), sections B and C are isolated from the water table and hence anaerobic conditions persist close to the surface.

We attribute peak carbon accumulation at intermediate elevation and distance from the coast partially to the enhanced rates of biomass input associated with dominant vascular plant colonisation and partially to the age of the deposits and the ecosystem maturity effect36. Although high decomposition has been measured in intermediate areas, the high biomass input increases the carbon accumulation rate. Where Sphagnum dominates, at the inland end of the transect, decomposition is minimal but biomass production is slow resulting in lower carbon accumulation. Carbon accumulation was lowest at the coastal interface because productivity was minimal and decomposition was high.

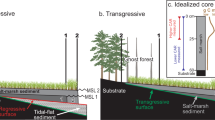

Over long time-scales, succession from saltmarsh to blanket bog requires the vertical growth of peat deposits and subsequent disconnection from the water table (ombrotrophication). Section C at Kentra Moss represents mature blanket bog and Section B represents a prior successional stage modulated by salt input, because coastward expansion has exploited areas exposed by falling Holocene sea levels. Palaeoenvironmental work at the site identified salt-marsh sediments underlying the blanket bog21, indicating that conditions equivalent to section A are the primary successional stage in the development of coastal blanket bog of this type. Indeed our results suggest that an environmental tipping point exists, governed by salt-water inundation, which limits blanket bog expansion coastward by facilitating high decomposition and inhibiting typical plant communities. Under the Holocene sea-level decline at Kentra Moss, blanket bog has expanded coastward, as new areas beyond the inundation level have been exposed, allowing succession of vegetation and increasing suppression of decomposition processes. This interpretation is corroborated by our peat depth measurements, which imply that peat initiation occurred earlier inland and spread toward the present coastline in agreement with previous studies21,22.

Modelling of near-future sea-level rise (Supplementary material 4) indicates that Kentra Moss is not immediately vulnerable, however our results from the salinity transect indicate that other similar coastal bogs that do experience sea intrusion may be under threat in the future. We infer a model of peatland ecosystem decline where increasing sea-level tips the salt concentrations over the tolerance threshold of freshwater peat-forming vegetation (Section B) allowing salt-marsh vegetation (Section A) to colonise the peat substrate left behind. This process is manifest on the West coast of Ireland where salt marshes currently colonise a peat substrate accumulated under freshwater conditions before a rise in sea-level37. If sea-level rise continued such conditions would precede states of total inundation, corresponding to complete loss of vegetation. Under such scenarios the areal extent of currently healthy blanket bog will decline along with their global contribution to the budget of atmospheric carbon sinks.

The decline in carbon sink functioning attributed to salt-water inundation at Kentra Moss highlighted the need for an estimation of the area of low-elevation coastal blanket bogs potentially vulnerable in the future. We then expanded our analysis to incorporate peatlands of all types. Our estimates also address an improvement of using peatland specific mapping suggested in previous work10. To make our estimates comparable we applied the same (Hydro1k) digital elevation model (DEM) to derive land-surface heights and made estimates of peatland loss under the same +5 m sea-level scenario.

Many of the blanket bog areas identified as at risk from rising sea level are also vulnerable to climatic changes in the future16. In total 11,500 km2 (~7.4% of the global total) of blanket bogs are located either at or below 5 m elevation. This equates to ca. 2.1 ± 0.34 Gt of stored carbon and a yearly carbon sink of 0.22 Tg.

Although our analysis was primarily aimed at quantifying blanket bog areas at risk, our global mapping shows that high-latitude peatlands, such as the blanket bog at Kentra Moss, are proportionately less vulnerable to sea-level change. This is attributed to their colonisation of more recently deglaciated land, areas now mostly experiencing isostatic rebound which contributes to low or negative rates of relative sea-level rise. In such areas active carbon accumulation and expansion coastward is likely, offsetting losses to rising sea levels elsewhere. The threat of inundation facing peatlands in the tropics is proportionately greater.

We identified Southeast Asia as the geographical region where the largest areas of peatland are threatened by sea-level change in the future (Supplementary material 5), supporting previous analysis10. Low-lying tropical peatlands are usually wooded (including mangroves) so the impacts of salinity in these areas may be very different from those at Kentra Bay. However, it is likely that in this region the threat of salt-water inundation will be exacerbated by recent land use changes38 (e.g. forest clearance and drainage for oil palm plantations) leading to rapid oxidation and wild-fires that eventually result in land subsidence39. Tropical peats subside rapidly after drainage by ~1.5 m after 5 years with continued loss at rates of ~3–5 cm yr−1, equivalent to surface lowering of 4–5 m over 100 years40. Similarly to the saltmarsh sediments underlying the blanket bog at Kentra Moss, tropical peat domes often originate from mangroves and floodplains either at or below sea level. Due to the depths of these peat deposits (mean >5 m and up to 20 m or more40,41) the subsidence of coastal lowland peatlands is a significant mechanism enhancing the threat of inundation that they face.

The risk of tropical peat collapse following saltwater intrusion has been suggested by research conducted in the Everglades National Park (USA), which is also highlighted as a high-risk region by our mapping (Fig. 4). A positive feedback may result from the intrusion of saltwater, a symptom of rising sea levels or increased storm surge frequency, causing sawgrass dieback and subsequent degradation of freshwater peat. Surface lowering allows water depths to rise inhibiting the establishment of plants, and high salinity means that soil is only stabilised after salt tolerant mangrove colonisation42.

Importantly ocean inundation of the peatlands does not necessarily imply that the carbon they store would be immediately oxidised and released as CO2 to the atmosphere. Oxidation of carbon after inundation is one possibility, but if peat experienced relatively rapid burial under sediment, then carbon stores could be maintained43, converted into lignite and eventually coal. In South-west England, peat substrates buried beneath beach deposits have recently been exposed, indicating that complete loss of carbon is not an inevitable consequence of inundation. Such features are widespread elsewhere in the United Kingdom44. However, whilst a peat substrate may remain intact post-inundation, loss of the peatland as an ecosystem is inevitable. Possible carbon losses, and the changing accumulation rates of inundated coastal peatlands, therefore represent a component of direct carbon flux laterally across the land-ocean aquatic continuum, which is currently uncertain.

Equally, predictions of short-term future sea-level rise do not implicate a global rise of 5 m, however the application of such a scenario is useful in highlighting the global extent and locations of low elevation peatlands. Indeed, the 1 km resolution of the DEM we applied allows the assumption that grid squares of 5 m average elevation include substantial land areas vulnerable to small increases in sea level. Also in the tropics where subsidence of already low lying coastal peatlands equivalent in magnitude to +5 m sea-level rise have been widely reported, the application of such a scenario is relevant for projecting change by 2100.

Unfortunately, a dataset of true peatland cover and distribution remains unavailable for many regions of the world2. Following this, we recognise that both estimations are made with a high degree of uncertainty stemming from a variety of sources (Table 3). Future refinements would benefit substantially from: accounting for global peat accretion and subsidence, modelling spatial variability in sea-level trends, mapping peatland extent with higher accuracy and by using more accurate and locally specific elevation datasets.

Once we take uncertainties into consideration, the impact of future global sea-level rise alone, at policy-relevant timescales, will be comparatively minor against other threats peatlands face. However, anthropogenic perturbation of natural peatlands (notably subsidence), will render some regions substantially more vulnerable to the threat of coastal inundation, even where absolute sea level does not change. Similarly other anthropogenic stresses on peatlands (e.g. shrinking of bioclimatic envelopes16) may increasingly mean that coastal peatlands either cannot keep pace with sea-level rise leading to eventual inundation, or cannot colonise areas exposed by falling sea levels, if these areas are no longer climatically suitable.

Conclusion

Our results linking variable salt-input with changes in peatland ecosystem functioning across the unbroken succession of salt marsh to ombrotrophic blanket bog at Kentra Moss indicate that concentrated salt input has a significant negative effect on the rate of recent carbon accumulation. Therefore, inundation by sea-level rise in the future represents a threat to blanket bog and peatlands more generally.

Through altering both the vegetation assemblages which colonise the bog and also the decomposition processes taking place within the peat matrix, inputs of oceanic base cations alter the carbon balance, and therefore exert control on surface accretion and carbon accumulation rates. The level of inundation (tidally and by storm surges) constrains the coastward colonisation of Sphagnum mosses, key builders of high-latitude peatlands. Blanket bogs are however sufficiently flexible to persist in areas of moderate concentrations of salt-input, and this allows them to expand coastward where sea level and climatic conditions allow. We estimate that the current extent of blanket bogs at very low elevation (≤5 m above sea level) is 11,500 km2 equating to a carbon store of ca. 2.1 ± 0.34 Gt.

Under scenarios of sea-level rise, where blanket bogs are inundated by salt-water, we forecast that an inland shift of all sections (A, B and C) will occur, i.e. saltmarsh (halophilic) plant communities will colonise the peat substrate and decomposition processes will change. This will correspond to a decline in carbon accumulation compared to blanket bogs. Globally, the blanket bog area vulnerable to future salt-water inundation is equivalent to a total sink of 0.22 Tg C yr−1.

We estimate that ~145,000 km2 of global peatlands containing 20.2 ± 2.5 Gt C are located ≤5 m above sea level. Our mapping of these vulnerable areas, the first of its type, may therefore be used to aid higher accuracy and targeted assessments of peatland vulnerability at the regional scale. We provisionally show that tropical peatlands are proportionally at greater risk (~16.6% of total area, 61,000 km2 and 8.3 ± 1 Gt of stored carbon). Following this, the region where peatlands face the greatest risk of inundation is South-east Asia, especially Kalimantan and Sumatra, where recent land-use change is resulting in rapid peatland subsidence. Generally, tropical peatland areas will suffer disproportionately relative to those at high latitude. This is because high-latitude (>40°N) peatlands have colonised land that is more likely to be recently deglaciated and many of these deglaciated areas are experiencing isostatic rebound. Rapid and significant peat subsidence will also amplify the risk of salt-water inundation facing peatlands in the tropics.

The inundation of peat by salt-water does not necessarily mean that all stored carbon would be oxidised however the overall contribution of freshwater peatlands as sinks in the global carbon cycle would inevitably be reduced. The impacts of peatland inundation are likely to be regionally important, especially in the tropics. In such regions the value of peatlands extends beyond their function as carbon sinks but rather as providers for livelihoods, provision of land as well as other essential ecosystem services41,45. Further consideration of the controlling influence of the ocean on sustainable peatland carbon accumulation should focus on the longer-term impacts associated with anthropogenic perturbation of the salt-water inundation risk at time-scales analogous to peatland accretion.

Methods

Field Methodology

We established a 450 m wide transect belt across the blanket bog at Kentra Bay, which stretched 2 km inland from the coastal interface, and avoided areas of historical disturbance (Fig. 1). We avoided sampling in immediate proximity to the various rock intrusions (Supplementary material 1) or the road intersecting the site.

We recorded variability in surface water conductivity (salinity) with distance inland along two transects, using a calibrated Hanna probe (HI 98129) which compensated values to a standard temperature. Conductivity is linearly related to salinity under the measuring conditions at the site and therefore makes a good proxy for salinity46. Two-hundred measurements of conductivity were taken alongside measurements of pH, total dissolved solids and temperature. Sampling of every existing pool enhanced data coverage at the coastal interface (0–200 m inland) where most variability was identified.

Thirteen cores spaced along the transect were sampled using monolith tins to a depth of 30 cm. Cores were taken mid-range between mounds and hollows on the peatland surface to control micro-topographic heterogeneity in accumulation47. Compaction and sampling losses were controlled for both techniques by cutting surface vegetation with a serrated knife before extraction of the cores48. Cores were wrapped in plastic film and refrigerated prior to subsampling.

Peat depth measurements were taken by inserting a metal probe vertically from the surface until the point of obstruction, interpreted as the interface with the underlying fluvioglacial fan (sand and gravel). Three separate transects were used to account for local scale depth variability.

We recorded the percentage cover of vascular plants, Sphagnum and other bryophyte species within metre-square quadrats spaced along the transect belt. Vegetation (canopy) height was recorded by measuring individual species present before calculating a quadrat average based on the percentage cover of each species.

Laboratory Methodology

Each monolith was subsampled at contiguous 1 cm resolution, ensuring constant sample volume (6.25 cm3). Bulk density was calculated by dividing sample mass after freeze-drying by volume49. Change of sample mass after drying determined the moisture content. Organic matter content was calculated from measurements of loss on ignition (550 °C for 4 hours) at 2 cm intervals, and converted to carbon content using a regression for British peat and organic soils50. Carbon density (gCcm−3) was calculated by multiplying bulk density with percentage carbon content4. Ash-free bulk density, a simple proxy for degree of peat decomposition, was derived from multiplying bulk density by organic matter content25,49.

A high-resolution chronology for five of the monolith cores was established using 210Pb dating. Samples were acid digested with concentrated HCl, HNO3, and H2O2, and a spike of 209Po added as a yield tracer. Material was plated onto silver disks and the activity measured by alpha spectrometry using an Ortec Octête Plus Integrated Alpha-Spectrometry System at the University of Exeter (UK) Radiometry Lab. Resulting activities were reported with 1-sigma analytical uncertainty. The ratio 210Po/209Po is calculated to derive the 210Pb activity, which is then corrected for sample size, decay rates and time between preparation and measurement. The date of each sample was derived from the 210Pb inventory using the constant rate of supply model51.

Due to leaching of 210Pb in sediments prone to significant water-table fluctuation52 Spheroidal Carbonaceous Particles (SCPs), a frequently applied technique53,54, were used as alternative dating features for the salt-marsh sediments proximal to the coast. SCP samples were prepared with a sequence of selective acid digestions55,56, and their presence within each sample counted under a microscope. SCP identification followed Rose (2008)57. Relative SCP concentrations per sample were deduced to identify two dating features; peak (1978 ± 4 AD) and initial take-off (1850 ± 25 AD)54. BACON, a flexible Bayesian age–depth modelling approach that uses prior information on likely accumulation rates and their plausible variability over time was used to produce an age-depth model from the results58. For all cores, three priors (the accumulation rate, section thickness and memory) were set to default values, (acc.shape = 1.5, acc.mean = 20, res = 5)58. Total carbon accumulation was calculated by identifying the depth of the year 1900, and totalling quantity of carbon within the core above (Supplementary material 6).

Computational Methodology

Field Site

Individual datasets from Kentra Bay were synthesised using ArcMap 10.2. We used a 5 m grid resolution digital terrain model (Ordnance Survey Terrain 5) to measure elevation above sea level and calculate distance inland for each individual data point. We defined the coast as the boundary between marine sediment and the first salt-marsh plants.

Mapping low elevation peatlands

Global Peatland Cover Map: A map of freshwater peatland areas was obtained from Yu et al.2. The map comprises data obtained from individual regional inventories of soil type (see reference for individual data sources).

Global Blanket Bog Map: We created a map of global blanket bog area by integrating mapped areas of bioclimatic suitability16 with the Global Peatland Cover Map. Data for both peatland and blanket bog cover was converted to a 1 km cell grid to standardise resolution for analysis.

Hydro1k Digital Elevation Model (DEM) is a hydrologically adjusted derivative of the GTOPO30 elevation dataset, with global coverage (excluding Greenland and Antarctica) at 1 km resolution (available from the U.S. Geological Survey). We applied this dataset because; (1) it has harmonized sea levels, (2) it has fixed values for open water, and (3) it makes our estimate of vulnerable peatland area comparable with a previous estimate for organic soils10.

Using ArcMap 10.2, peatlands at 2, 5 and 10 m above sea level were isolated using elevation values derived from the DEM. This provided a numerical vulnerability score for each cell containing peatland and a corresponding total area of at risk peatlands. The same technique was applied for blanket bog areas. A correction factor was employed to equalise the global peatland area indicated by the peat map with accepted values from the literature2,4. Disparity in peatland coverage estimation arises because; (1) the map indicates peatland abundant regions (peat cover ≥5%) rather than true coverage2, (2) there is spatial variability within the inventories used to assemble the dataset, and (3) the differential classification of peatlands between countries.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Whittle, A. and Gallego-Sala, A. V. Vulnerability of the peatland carbon sink to sea level rise. Sci. Rep. 6, 28758; doi: 10.1038/srep28758 (2016).

References

Yu, Z. et al. Peatlands and their role in the global carbon cycle. Eos 92, 97–108 (2011).

Yu, Z., Loisel, J., Brosseau, D. P., Beilman, D. W. & Hunt, S. J. Global peatland dynamics since the last glacial maximum. Geophysical Research Letters 37, L13402 (2010).

Limpens, J. et al. Peatlands and the carbon cycle: from local processes to global implications – a synthesis. Biogeosciences 5, 1475–1491 (2008).

Charman, D. J. et al. Climate-related changes in peatland carbon accumulation during the last millennium. Biogeosciences 10, 929–944 (2013).

Page, S. et al. Restoration ecology of lowland tropical peatlands in Southeast Asia: current knowledge and future research directions. Ecosystems 12, 888–905 (2009).

Rydin, H. & Jeglum, J. K. The Biology of Peatlands 2nd edn. (Oxford University Press, 2013).

Charman, D. J. Peatlands and Environmental Change. (Wiley, 2002).

Tarnocai, C. The effect of climate change on carbon in Canadian peatlands. Global and Planetary Change 53, 222–232 (2006).

Charman, D. J., Laine, J., Minayera, T. & Sime, A. Impacts of future climate change on peatlands In Assessment on Peatlands, Biodiversity and Climate Change: Main Report (eds Parish, F. et al.) Ch. 8, 139–154 (Global Environment Centre and Wetlands International, 2008).

Henman, J. & Poulter, B. Inundation of freshwater peatlands by sea level rise: uncertainty and potential carbon cycle feedbacks. Journal of Geophysical Research 113, G01011 (2008).

Chambers, L. G. et al. Biogeochemical effects of simulated sea level rise on carbon loss in an everglades mangrove peat soil. Hydrobiologia 726, 195–211 (2014).

Rhein, M. et al. Observations: Ocean In Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution to the Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Stocker, T. F. et al.) Ch. 3, 255–316 (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Wong, P. P. et al. Coastal systems and low-lying areas In Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaption and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Field, C. B. et al.) Ch. 5, 361–409 (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

Cott, G. M., Jansen, M. A. K. & Chapman, D. V. Salt-Marshes on peat substrate: where blanket bogs encounter the marine environment. Journal of Coastal Research 28, 700–706 (2012).

Merila, P. et al. Methanogen communities along a primary succession transect of mire ecosystems. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 55, 221–229 (2006).

Gallego-Sala, A. V. & Prentice, C. I. Blanket peat biome endangered by climate change. Nature Climate Change 3, 152–155 (2013).

Billett, M. F. et al. Carbon balance of UK peatlands: current state of knowledge and future research challenges. Climate Research 45, 13–29 (2010).

Kleinebecker, T., Hölzel, N. & Vogel, A. South patagonian ombrotrophic bog vegetation reflects biogeochemical gradients at the landscape level. Journal of Vegetation Science 19, 151–160 (2008).

Vitt, D. H., Horton, D. G., Slack, N. G. & Malmer, N. Sphagnum-dominated peatlands of the hyper oceanic British Columbia coast: patterns in surface water chemistry and vegetation. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 20, 696–711 (1990).

Zong, Y. & Horton, B. P. Diatom-based tidal-level transfer functions as an aid in reconstructing quaternary history of sea-level movements in the UK. J. Quaternary Sci. 14, 153–167 (1999).

Shennan, I., Innes, J. B., Long, A. J. & Zong, Y. Holocene relative sea-level changes and coastal vegetation history at Kentra Moss, Argyll, Northwest Scotland. Marine Geology 124, 43–59 (1995).

Ellis, C. J. & Tallis, J. H. Climatic control of blanket mire development at Kentra moss, North-west Scotland. Journal of Ecology 88, 869–889 (2000).

Shennan, I. & Horton, B. Holocene land- and sea-level changes in Great Britain. J. Quaternary Sci. 17, 511–526 (2002).

Met Office, Regional Climate Data. (2015) Available at: www.metoffice.gov.uk/climate/uk/datasets. (Accessed: 1st January 2016).

Yu, Z. et al. Carbon sequestration in Western Canadian peat highly sensitive to Holocene wet-dry climate cycles at millennial timescales. The Holocene 13, 801–808 (2003).

Magnan, G., Garneau, M. & Payette, S. Holocene development of maritime ombrotrophic peatlands of the St. Lawrence North shore in Eastern Canada. Quaternary Research 82, 96–106 (2014).

Niklas, K. J. & Enquist, B. J. Invariant scaling relationships for interspecific plant biomass production rates and body size. PNAS 98, 2922–2927 (2001).

Clymo, R. S., Kramer, J. R. & Hammerton, D. Sphagnum-dominated peat bog: a naturally acid ecosystem. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 305, 487–499 (1984).

Shotyk, W. Atmospheric deposition and mass balance of major and trace elements in two oceanic peat bog profiles, Northern Scotland and the Shetland Islands. Chemical Geology 138, 55–72 (1997).

Van Breemen, N. How sphagnum bogs down other plants. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 10, 270–275 (1995).

Freeman, C., Ostle, N. & Kang, H. An enzymic ‘latch’ on a global carbon store. Nature 409, 149 (2001).

Loisel, J., Gallego-Sala, A. V. & Yu, Z. Global-scale pattern of peatland sphagnum growth driven by photosynthetically active radiation and growing season length. Biogeosciences 9, 2737–2746 (2012).

Pouliot, R., Rochefort, L. & Graf, M. D. Fen mosses can tolerate some saline conditions found in oil sands process water. Environmental and Experimental Botany 89, 44–50 (2013).

Malmer, N., Svensson, B. M. & Wallén, B. Interactions between Sphagnum mosses and field layer vascular plants in the development of peat-forming systems. Folia Geobotanica and Phytotaxonomica 29, 483–496 (1994).

Gauci, V., Dise, N. & Fowler, D. Controls on suppression of methane flux from a peat bog subjected to simulated acid rain sulfate deposition. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 16, 1004 (2002).

Yu, Z. C., Vitt, D. H., Campbell, I. D. & Apps, M. J. Understanding Holocene peat accumulation pattern of continental fens in Western Canada. Canadian Journal of Botany 81, 267–282 (2003).

Cott, G. M., Chapman, D. V. & Jansen, M. A. K. Salt marshes on substrate enriched in organic matter: the case of ombrogenic Atlantic salt marshes. Estuaries and Coasts 36, 595–609 (2013).

Page, S. E., Rieley, J. O. & Banks, C. J. Global and regional importance of the tropical peatland carbon pool. Global Change Biology 17, 798–818 (2011).

Hooijer, A. et al. Current and future CO2 emissions from drained peatlands in Southeast Asia. Biogeosciences 7, 1505–1514 (2010).

Hooijer, A. et al. Subsidence and carbon loss in drained tropical peatlands. Biogeosciences 9, 1053–1071 (2012).

Yule, C. M. Loss of biodiversity and ecosystem functioning in Indo-Malayan peat swamp forests. Biodiversity and Conservation 19, 393–409 (2010).

Chambers, L. G., Davis, S. E. & Troxler, T. G. Sea level rise in the Everglades: plant-soil-microbial feedbacks in response to changing physical conditions In Microbiology of the Everglades Ecosystem (eds Entry, J. A. et al.) (CRC Press, 2015).

Jordan, J. W. & Mason, O. K. A 5000 year record of intertidal peat stratigraphy and sea level change from Northwest Alaska. Quaternary International 60, 36–47 (1999).

Historic England, Intertidal and Coastal Peat Database. (2015) Available at: www.historicengland.org.uk/research/current-research/heritage-science/intertidal-peat-database. (Accessed: 1st January 2016).

Giam, X. et al. Global extinctions of freshwater fishes follow peatland conversion in Sundaland. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 10, 465–470 (2012).

Wagner, R. J., Boulger, R. W. Jr., Oblinger, C. J. & Smith, B. A. Guidelines and standard procedures for continuous water-quality monitors – station operation, record computation, and data reporting: U.S. Geological survey techniques and methods 1-D3. ( 2006) Available at: http://pubs.water.usgs.gov/tm1d3. (Accessed: 1st January 2016).

De Vleeschouwer, F., Chambers, F. M. & Swindles, G. T. Coring and sub-sampling of peatlands for paleoenvironmental research. Mires and Peat 7, 1–10 (2010).

Parry, L. E., Charman, D. J. & Noades, J. P. W. A method for modelling peat depth in blanket peatlands. Soil Use and Management 28, 614–624 (2012).

Chambers, F. M., Beilman, D. W. & Yu, Z. Methods for determining peat humification and for quantifying peat bulk density, organic matter and carbon content for palaeostudies of climate and peatland carbon dynamics. Mires and Peat 7, 1–10 (2011).

Bol, R. A., Harkness, D. D., Huang, Y. & Howard, D. M. The influence of soil processes on carbon isotope distribution and turnover in the British uplands. European Journal of Soil Science 50, 41–51 (1999).

Appleby, P. G. Chronostratigraphic techniques in recent sediments in Tracking environmental change using lake sediments Vol. 2: Physical and geochemical methods (eds Last, W. M. & Smol, J. P. ) 171–203 (Springer, 2001).

Belyea, L. R. & Warner, B. G. Dating of the near-surface layer of a peatland in Northwestern Ontario. Boreas 23, 259–269 (1994).

Garnett, M. H., Ineson, P. & Stevenson, A. C. Effects of burning and grazing on carbon sequestration in a Pennine blanket bog, UK. The Holocene 10, 729–736 (2000).

Rose, N. L. & Appleby, P. G. Regional applications of lake sediment dating by spheroidal carbonaceous particle analysis I: United Kingdom. Journal of Paleolimnology 34, 349–361 (2005).

Rose, N. L. A note on further refinements to a procedure for the extraction of carbonaceous fly-ash particles from sediments. Journal of Paleolimnology 11, 201–204 (1994).

Swindles, G. T. Dating recent peat profiles using spheroidal carbonaceous particles (SCPs). Mires and Peat 7, 1–5 (2010).

Rose, N. Quality control in the analysis of lake sediments for spheroidal carbonaceous particles. Limnol. Oceanogr.: Methods 6, 172–179 (2008).

Blaauw, M. & Christen, J. A. Flexible paleoclimate age-depth models using an autoregressive gamma process. Bayesian Analysis 6, 457–474 (2011).

Chambers, L., Osborne, T. & Reddy, K. Effect of salinity-altering pulsing events on soil organic carbon loss along an intertidal wetland gradient: A laboratory experiment. Biogeochemistry 115, 363–383 (2013).

Phillips, S., Bustin, R. M. & Lowe, L. E. Earthquake-induced flooding of a tropical coastal peat swamp: a modern analogue for high-sulfur coals? Geology 22, 929–932 (1994).

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Dr. Zicheng Yu at Lehigh University for providing the map of global peatlands, and Dr. Damien Mansell (University of Exeter) who helped with data processing. Our thanks also go to Dr. Lisa Orme and Nicole Sanderson for laboratory support with 210Pb dating, and to Scottish Natural Heritage for arranging access to the site. We thank Howard Bowman for insightful comments on the initial manuscript draft. We are also grateful to the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC grant number NE/I012915/1) for the funding to support the work presented in this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.W. carried out; initial fieldwork, laboratory analysis of samples used in the report, and wrote the first draft. A.V.G.-S. supervised the project, oversaw subsequent fieldwork and contributed to data analysis and the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Whittle, A., Gallego-Sala, A. Vulnerability of the peatland carbon sink to sea-level rise. Sci Rep 6, 28758 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep28758

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep28758

This article is cited by

-

Expert assessment of future vulnerability of the global peatland carbon sink

Nature Climate Change (2021)

-

Widespread subsidence and carbon emissions across Southeast Asian peatlands

Nature Geoscience (2020)

-

Salt-Enrichment Impact on Biomass Production in a Natural Population of Peatland Dwelling Arcellinida and Euglyphida (Testate Amoebae)

Microbial Ecology (2019)

-

Declines in Plant Productivity Drive Carbon Loss from Brackish Coastal Wetland Mesocosms Exposed to Saltwater Intrusion

Estuaries and Coasts (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.