Abstract

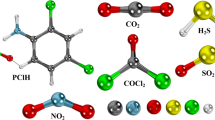

In this research, we investigated the sorptive behavior of a mixture of 14 volatile and semi-volatile organic compounds (four aromatic hydrocarbons (benzene, toluene, p-xylene, and styrene), six C2-C5 volatile fatty acids (VFAs), two phenols, and two indoles) against three metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), i.e., MOF-5, Eu-MOF, and MOF-199 at 5 to 10 mPa VOC partial pressures (25 °C). The selected MOFs exhibited the strongest affinity for semi-volatile (polar) VOC molecules (skatole), whereas the weakest affinity toward was volatile (non-polar) VOC molecules (i.e., benzene). Our experimental results were also supported through simulation analysis in which polar molecules were bound most strongly to MOF-199, reflecting the presence of strong interactions of Cu2+ with polar VOCs. In addition, the performance of selected MOFs was compared to three well-known commercial sorbents (Tenax TA, Carbopack X, and Carboxen 1000) under the same conditions. The estimated equilibrium adsorption capacity (mg.g−1) for the all target VOCs was in the order of; MOF-199 (71.7) >Carboxen-1000 (68.4) >Eu-MOF (27.9) >Carbopack X (24.3) >MOF-5 (12.7) >Tenax TA (10.6). Hopefully, outcome of this study are expected to open a new corridor to expand the practical application of MOFs for the treatment diverse VOC mixtures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Emissions of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and semi-volatile organic compounds (SVOCs: volatile fatty acids (VFAs), phenolic, and indolic compounds) and their resulting impact on human health are a major environmental concern1,2,3. Exposure of many of these pollutants has indeed been identified as the causes of diverse (both acute and chronic) health problems4. To date, many types of conventional technologies employing diverse classes of materials (e.g., activated carbon, zeolites, and hybrid materials) have been tested for their feasibility toward chemical and physical sorption applications5. These technologies have a number of shortcomings or limitations including limited adsorption capacity, toxic end products, and high energy costs for regeneration6. In pursuit of a viable means to resolve such problems, the potent role of metal organic frameworks (MOFs) has been recognized due to many advantageous features including high surface area, enhanced gas/vapor adsorption, high catalytic activity, thermal/chemical stability, and tailorable pore sizes. As such, MOFs can be used as excellent adsorbent materials to treat diverse VOCs and VFAs7,8.

In recent years, the use of pendant and incorporated functional groups (e.g., carboxyl) during post and pre-synthesis has been demonstrated as a simple methodology for increasing adsorption/removal capacity and selectivity toward various gaseous and aqueous phase pollutants9,10,11,12,13. For example, MOF-199 exhibited good adsorption capacity for benzene as 511 mg g−1 at 308 K (1.5 mbar partial pressure and 34% relative humidity (RH))14. Likewise, NENU-511 was estimated to have adsorption capacity for benzene as 1.56 g.g−1 (or 0.61 g.mL−1) at its saturated vapor pressure15. The adsorption capacity (mg g−1) of toluene and p-xylene on MIL-101 was also measured as 48.8 (at 298 K and 101 kPa)16 and 1155 (at 288 K and 5.98 mbar)17, respectively. Likewise, some studies were carried out to assess the adsorption behavior of SVOCs on MOFs. The zirconium-based isorecticular MOFs (namely UiO-66 and UiO-66-NH2) recorded adsorption of indole at 298 K up to 213 and 312 mg g−1, respectively in an aqueous phase based on the strong hydrogen bonding mechanism18. The adsorption of phenol on NH2-MIL-101(Al) was also measured as 37.6 mg g−1 in the aqueous phase at 303 K19.

To date, numerous reports have been made to describe the adsorption capacity (and characteristics) of MOFs against common VOCs like aromatic hydrocarbons (e.g., benzene, toluene, and xylene)14,20,21,22,23,24. There is yet a paucity of quantitative data on their capacity toward semi-volatile organic species such as C2–C5 VFAs, phenolic, and indolic compounds. In fact, the presence of excessive SVOC levels have been recognized as one of the major concerns in: natural gas treatment25,26,27,28, animal housing facilities29,30,31, and sewage treatment plants32,33. Nonetheless, information regarding their treatment approaches is scanty due to their complex physiochemical properties (relative to common VOCs).

In order to fill up our knowledge gaps and to help construct a quality MOF performance database, we investigated the sorption behavior of three well-known MOFs (namely MOF-5, Eu-MOF, and MOF-199) toward a mixture of 14 VOCs (consisting of both volatile and semi-volatile species with varying polarities) at 5 to 10 mPa partial pressures (25 °C). The selection of these three MOFs was made based on their –COOH terminating nature along with easy accessibility (such as preparation methods, storage, and structural characteristics). Because of the commercial availability of these MOFs, our study will help open a route for further investigations for their large-scale applications. As MOFs are also employed as sorbents for analytical purpose (e.g., thermal desorption analysis of gaseous pollutants)34,35, the performance of these selected MOFs was investigated in reference to three well-known commercial adsorbents (i.e., Tenax TA, Carbopack X, and Carboxen 1000). Hence, our report will also help extend their feasibility as media for gas sampling. In addition, the adsorption mechanism of selected MOFs was also evaluated based on the density functional theory (DFT) and spectroscopic measurements.

Results and Discussion

Assessment of conversion efficiency of liquid working standard (LWS) to gaseous working standard (GWS) between different target volatiles

In this study, the adsorptive removal of a mixture of 14 VOCs (i.e., four volatile aromatic hydrocarbons (benzene (B), toluene (T), p-xylene (p-X), and styrene (S)), and ten semi-volatile organic compounds (acetic acid (ACA), propionic acid (PPA), isobutyric acid (IBA), butyric acid (BTA), isovaleric acid (IVA), valeric acid (VLA), phenol (PHN), p-cresol (p-C), indole (IN), and skatole (SK)) was assessed using three types of MOFs (MOF-5, Eu-MOF, and MOF-199) at ambient conditions (Tables 1 and 2). Their performance was also compared against three well-known commercial adsorbents, namely: Tenax TA, Carbopack X, and Carboxen-1000. As shown in Fig. 1, three types of experiments were designed and conducted to test the removal efficiency of the MOFs and commercial adsorbents.

In general, the preparation and/or storage of vapor-phase SVOCs (e.g., in the ppb range) are very problematic due to sorptive losses occurring on the surface of materials employed for such purposes (including storage medium, sample tubing, and valves)36. Note that the occurrences of such losses depend on the combined effects of several key controlling factors such as volatility (increased losses for semi-volatile species) and storage time. Consequently, primary gas standards for semi-volatile species are generally not available. Thus, the assessment of gas-phase recoveries (prepared by the vaporization of liquid standard) is important due to the complex physiochemical properties of the selected VOCs (Tables S1 and S2)37. Table S3 shows the calibration response factor (RF) values (ng−1) of the GWSs obtained based on fixed standard concentration (FSC) approaches (FSC-1 to FSC-4)38. The RF values of phenolic compounds in the GWS were lower than those of LWS by about 50% (PHN = 6,289 ± 1309 and p-C = 4,694 ± 753 ng−1). The maximum loss (about 90%) was observed for indoles (IN = 2,649 ± 573 and SK = 3,137 ± 372 ng−1) due to their high adsorption on the polyester aluminum (PEA) bag surface33. The relative standard error (RSE (%)) of the VFAs was below 5% in most cases (except ACA), while the phenols and indoles had values below 10%. The rise in RSE (%) for the semi-volatile species is likely due to their physiochemical properties.

The relative recovery (RR) of each target compound in the GWS was calculated by computing the ratio of their RF values between two standard types (Table S4). The VFAs had a mean RR of 52.0 ± 2.01% (n = 6 compounds), while phenols (n = 2) and indoles (n = 2) were 25.0 ± 3.0 and 8.9 ± 0.3%, respectively. This pattern of significant losses is comparable to what was found previously in many studies on various bag types33,36,39,40,41,42. The actual concentrations in each GWS were thus estimated using the RR data (Table S4). For Experiments 1 and 2, 20 L of the GWS in a 20 L PEA bag were used. Tables S5 and S6 provide the RR data for 20 L GWS. The VFAs had a mean recovery of 46.1 ± 2.7% (n = 6 compounds), while those of phenols and indoles (n = 2, 2) were 34.2 ± 16.8 and 18.6 ± 5.3%, respectively.

Characterization of synthesized MOFs

The basic properties (e.g., degree of crystallinity, the chemical functionality, the morphology, and the surface area) were examined using powder X-ray diffraction studies (PXRD), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and N2 adsorption and desorption studies, respectively (Fig. 2). The two MOF-5 FTIR peaks at 1385 and 1579 cm−1 indicated the attachment of the carboxylate ligand to the Zn4O center43. Likewise, the peaks located near 816, 746, and 653 cm−1 confirmed Zn-O stretching modes. IR bands at 1502, 1294, and 653 cm−1 indicated a random dimethyl formamide (DMF) distribution in the MOF-5 framework structure44. The band located at 3607 cm−1 indicated adsorbed water molecules. The Eu-MOF showed peaks at 1530 and 1582 cm−1, which were attributed to the symmetric and asymmetric C = O stretching vibrations, respectively. Compared with the free carboxyl groups (~1700 cm−1), the presence of a low wavenumber peak indicates the possible coordination between carboxyl groups of the ligand with Eu5+ (Ref. 45). The strong peaks around 665 and 779 cm−1 were attributed to the Eu-O stretching vibrations resulting from successful coordination between Eu3+ and the carboxylic group46. The FTIR spectra of the synthesized MOF-199 showed a narrow band around 2931 cm−1 indicating the presence of –CH3 groups in DMF. The peaks at 760.2 and 727.9 cm−1 were due to Cu coordination to BTC, while those located at 1106.9 and 939.7 cm−1 were due to C-O-Cu stretching vibrations47. The asymmetric stretching vibrations of the carboxylate group were observed at 1641.9 cm−1, whereas symmetric modes were observed at 1442.3 and 1372.9 cm−148.

The observed PXRD peaks of Eu-MOF were in good agreement with the reported data46. The main MOF-199 diffraction peaks (at 2θ = 6.7, 9.4, 11.6, 13.4, 17.4, 19.0, and 29.4) confirmed its structure49,50. Likewise, the MOF-5 peaks are also in excellent agreement with the literature using a similar synthesis procedure3. As seen in Fig. 2, SEM images of MOF-5 showed cubic crystals3, while MOF-199 crystals have an octahedral morphology in agreement with Zhao et al.14. In contrast, Eu-MOF exhibited a grass-like structure (~20 μm) in agreement with its reported morphologies46.

The Langmuir surface area of the synthesized MOF-5 (535 m2 g−1 ) was lower than that reported previously (895 m2 g−1)3; this could be due to solvent molecules being trapped in the MOF-5 cages3 with the estimated total pore volume of 0.22 cm3 g−1. In the case of Eu-MOF and MOF-199, the Langmuir surface area values were 281 and 1591 m2 g−1, respectively, while the corresponding total pore volume was 0.95 and 0.46 cm3 g−1, respectively; these results are also in good agreement with previous work51,52. The corresponding N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms are shown in Fig. S1.

Adsorption capacity

The equilibrium adsorption capacities (q) were calculated according to

where q (mg g−1) is the adsorption capacity, Cin and Cout are inlet and outlet concentrations of gaseous compounds, respectively, ΔV is sample volume (1 L) (Table 3). It should be noted that sorbent saturation for some tested MOFs was not attained within 15 L sample loading, e.g., skatole on MOF-199 (Fig. 3). To allow comparative analysis of performance between MOFs and commercial sorbents, breakthrough was also determined. The estimated equilibrium adsorption capacities of MOFs are only applicable to partial pressures of ~0.01 Pa; it should thus be noted that such estimates are unlikely to directly correspond to the maximum MOF adsorption capacities measured at higher VOC partial pressures (e.g., 10,000 Pa).

Although quartz wool (QW) is used to support and hold the sorbent media in the sorbent bed, it can also act as a very weak sorbent53. Moreover, in many studies carried out with sorbent tube sampler, QW is generally used as a supporting medium for analytical purposes. Their affinity is minimal for aromatic hydrocarbons but found to be maximum for SVOCs and PAHs54. Hence, in this study we tried to evaluate the sorptive losses of SVOCs due to the quartz wool by measuring its sorptive capacity like other sorbent materials.

The results showed contrasting patterns between different compounds for both empty and QW filled sorbent beds. Analyte loss was negligible or the smallest for aromatic hydrocarbons, while it was rather moderate to large for other targets like VFAs, phenolics and indolic species. For ACA, the detected mass (mD) exiting the sorbent bed packed with ~50 mg QW can be expressed as: slope (0.398)*(mass loaded (mL) + intercept). The intercept of −12.8 ng corresponds to a detection threshold (DT) of 32 ng55. DT is the minimum mass loaded at which breakthrough (BT) can occur. DT ranged from ~0 (aromatic hydrocarbons) to ~400 ng (p-cresol). As such, the slopes calculated for mD vs. mL (if mL > DT) varied from 0.398 (ACA) to ~1 (aromatic hydrocarbons). As such, it is important to employ an exact analytical method to estimate the errors associated with the sampling devices and the sorbent medium when measuring ambient indoor air quality. Hence, to adjust the effect of all unknown factors contributing to the analyte losses (silicone rubber and other components), the loss fraction (LF) of analyte mass needs to be subtracted from the total mass sorbed (qtot) to obtain the mass of each VOC sorbed (qs) only on a tested sorbent (Eqn. 2),

As there was some variability in assembling the apparatus, the LF will vary from experiment to experiment. The determination of the LF was done graphically as shown in Fig. S2 for three reference sorbents (Tenax TA, Eu-MOF, and Carbopack X). LF values were adjusted to obtain near horizontal plots for both qs and the Henry’s law constant (HLC, mol kg.−1 Pa−1) (Fig. S2); e.g., valeric acid/Carbopack X (Fig. S2 (a)). Here,

where MW is the molecular weight of a given VOC (g mol−1). The detection threshold was not considered in Eqn. (2), and it was set to 0; the obtained HLC adsorption, capacity, and LF data are summarized in Table S7. The LF values varied from 0.05 (benzene) to 0.62 (indole).

The mean equilibrium adsorption capacities (after QW correction) for the four aromatic (C6–C8) hydrocarbons were noticeably lower (MOF-199: >13.8 and Eu-MOF: 3.56 mg g−1) than those of the VFAs (MOF-199: 18.6 and Eu-MOF: 15.3 mg g−1). However, MOF-199 demonstrated maximum equilibrium adsorption capacities for phenols (27.9 mg g−1) and indoles (12.2 mg g−1) (Table 3). If expressed as Henry’s constants (mol kg−1 Pa−1) (Table S7), the MOF-199 values for benzene, toluene, and p-xylene in the present work (at 298 K) are comparable to those of MOF-1, MIL-47, and IRMOF-1 extrapolated to 298 from 448 K using the van’t Hoff equation and reported isosteric ΔHab56. For instance, in the case of toluene, the Henry’s constant of MOF-199 (>5.3), in this work is comparable to that of MOF-1 (14.2)56. However, for the benzene/MOF-199 system at 298 K, our Henry’s constant (>2.1) at a benzene pressure of 0.0081 Pa is significantly larger than the 5.08 × 10−2 (at a benzene pressure of 44 Pa) calculated from the data given by Yang et al.57. Qualitatively, our Henry’s constants for the aromatic hydrocarbons are in fair agreement with the literature, after appropriate adjustment for low partial pressures58.

Although open electron deficient metal sites are reactive species in MOFs, some of the electron rich species (i.e., Lewis bases like benzene) had very low affinity. Indeed, the square 4-coordinated open copper metal sites may be responsible for the high adsorption of MOF-199. These sites may also act as a Lewis acid/base depending on the functionality of the framework. This mechanism illustrates the heterogeneity and guest size dependency (size selectivity effect) of MOF-199 toward the target compounds. In addition, the adsorption mechanism of the Eu-MOF can be accounted for by defect-free nano sized (~2 nm) coordination sites in the framework and a comparatively low adsorption energy of the partially filled 4f electrons during adsorption51.

The MOF-5 exhibited remarkably reduced equilibrium capture capacities for all target analytes (Table S7) (aromatic hydrocarbons: ~0 mg.g−1, VFAs: 7.33 mg.g−1, phenols: >1.50 mg.g−1, and indoles: 3.90 mg.g−1). Consequently, the measured concentrations in the outlet were in some occasions higher than those of the inlet (Cout/Cin = ~1.2) (Fig. 3). This is because in a multicomponent analysis, compounds with a weaker MOF interaction can be challenged and displaced by a more strongly adsorbing species during dynamic adsorption. This phenomenon was evident for aromatic compounds (B, T, and p-X) and some VFAs (IVA and VLA). We suspected that this observation indicates the occurrence of “roll-up”. This poor performance of MOF-5 may be attributable to the highly cubic pore structure, which is reported to diminish the framework functionality during dynamic adsorption7.

To the best of our knowledge, there have been virtually no efforts to address the relative adsorption behavior of MOFs for different components with various volatilities as used in this study. Hence, to establish some comparative reference data, the performances of three well-known commercial adsorbents were also analyzed. Among those, Carboxen-1000 showed the highest mean equilibrium adsorption capacity for all target VOCs (aromatics: >22.2 mg g−1, VFAs: >23.4 mg g−1, phenols: >20.0 mg g−1, and indoles: 2.80 mg g−1). In contrast, such values were considerably reduced in the case of Carbopack X (aromatics: 3.74 mg g−1, VFAs: 10.2 mg g−1, phenols: 5.20 mg g−1, and indoles: 4.10 mg g−1) and Tenax TA (aromatic hydrocarbons: 0.96 mg g−1, VFAs: 3.85 mg g−1, phenols: 2.50 mg g−1, and indoles: 3.30 mg g−1). The increased equilibrium sorption capacity of the Carboxen-1000 may be due to its high surface area (1200 m2 g−1) compared to the other two commercial adsorbents (e.g., Tenax TA (36 m2 g−1) and Carbopack X (240 m2 g−1)).

Estimation based on DFT calculations

The interactions between MOFs and target compounds can be evaluated more meaningfully by considering the structure of the target species. For instance, toluene, phenol, and indole contain six-member aromatic rings. However, phenol (and butyric acid) has a polar –OH group, while indole has a polar N-H group in a five-member ring. Results of DFT calculations (Fig. 4a–c) demonstrate a number of bonding modes for the same compound with different MOFs. In the case of MOF-5 (with small pores), its interaction with the six-membered ring compounds is similar to AA stacking in graphite when both rings were placed one above the other. In contrast, the less dense MOF-199 showed more energetically favorable coupling (similar to the AB-stacking in graphite) when the rings of both phenol and toluene were shifted by the host MOF rings (Fig. 4a,b). This stacking information allowed us to assess different energies of π-π interactions between molecules and the benzene-ring structure of MOF-199. In addition, it may also be ascribable to the favorable interactions between the polar parts of the guest molecules and the Cu-ions of the MOF-199. In the case of MOF-5, no such interactions between the polar parts of the guest molecules and the Zn-ions were clearly seen based on the orientation of -OH groups (Fig. 4c). This contrasts to that of MOF-199 in which interactions occur despite the larger H-Cu distance orientation of -OH groups.

Atomic structure of MOF before and after adsorption of VOCs: Top (a) and side (b,c) views of optimized atomic structures of MOF-199 (a,b) and MOF-5 (c) with adsorbed toluene (left) and phenol (right) molecules. Interatomic distances indicated on the figure are in Å. Parts of the atomic structure of both MOFs are omitted for clarity.

We are able to explain the differences in the calculated change in Gibb’s free energy (ΔGad) values between MOF-5 and MOF-199 (Table S8) based on the observed differences in adsorption. The polarity of the guest molecule influenced the MOF-5 ΔGad,; i.e., toluene was −4.0 kJ mol−1 while phenol was −10.2 kJ mol−1. This result suggests that the replacement of a nonpolar –CH3 group with a polar –OH can enhance the adsorption efficiency. This is even more effective for MOF-199 due to the presence of an additional bond between the guest molecule and Cu-ion, while the influence of polarity almost doubled the binding energies (Table S8) (e.g., ΔGad value for toluene was −39.9 kJ mol−1, while those of phenols and indoles were −53.9 and 56.8 kJ mol−1, respectively). Our estimated 298 K ΔGad value for toluene/MOF-199 of −39.9 kJ mol−1 is comparable to 298 K ΔGad values for MOF-1, MOF-47, and IRMOF of −46.1, −44.2, and −25.3 kJ mol−1, respectively56. To this end, the selection of the MOFs for the adsorption process can be highly dependent on the availability of the π-orbitals for guest interaction as well as favorable host-guest interactions based on the framework polarity.

The microscopic mechanism of the host-guest interaction was also investigated in terms of changes in the chemical structural properties before and after the adsorption of guest molecules on MOFs by infrared spectroscopy (Fig. S3). The framework structure of all three MOFs remained intact before and after adsorption. In addition, the FTIR results suggest favorable π-π interactions of the guest molecules with COO− and C = C regions in the MOFs. The detailed description was given in the supplementary information.

Conclusions

The adsorption capacities of three MOFs (MOF-5, Eu-MOF, and MOF-199) toward a mixture of 14 gaseous volatile and semi-volatile organic species (partial pressures ~0.01 Pa) were analyzed and compared against three conventional sorbents (namely Tenax TA, Carbopack-X, and Carboxen-1000) at ambient conditions. In conclusion, MOF-199 showed the highest equilibrium adsorption capacity for all 14 VOCs of ~72 mg.g−1 followed by Eu-MOF (28 mg.g−1) and MOF-5 (13 mg.g−1) when 15 L of a ~100 ppb (~0.01 Pa) gaseous standard was loaded at ~25 °C. Our experimental results suggest that adsorption mechanism for MOF-199 was most favorable due to the presence of open metal sites in the framework. In addition, our DFT simulation analysis showed that presence of strong π-π interactions (MOF-199 >Eu-MOF (27.9) >MOF-5) and polarity of the guest molecule were the key factors influencing the sorption. Furthermore, the irreversibility of the MOF adsorption needs to be validated further (despite the fact that the adsorption Gibbs free energies provide an indication) and should be compared to conventional sorbents such as Carboxen-1000 and Tenax-TA. Most importantly, our study results are expected to provide valuable insights into the sorptive capacity of MOFs against many important hazardous and/or odorous volatile pollutants in indoor environment.

Materials and Methods

Experimental design

The synthesis of MOF-5 followed previous work with some modifications3. Likewise, nano-sized Eu-MOF was synthesized according to the procedure of Choi et al.51, while the blue uniform crystals of the MOF-199 were synthesized by following the procedure of Millward et al.52.

The synthesized MOF products were characterized and verified by using PXRD (Bruker D8 Focus diffractometer), SEM (Mini-SEMSNE-4000M), and Attenuated reflectance method (ATR)-FTIR spectroscopy (PerkinElmer L1600400–IR spectrometer). A diffraction analysis was performed on a standard glass slide for background correction. The data were recorded over a 2θ range of 5–35°. Specific surface area and pore parameters were estimated from N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms at 77 K using a Micrometrics ASAP 2010. Prior to experiments, MOF samples were heated at 423 K for 8 h under a reduced pressure of 133.3 Pa to remove adsorbed water and gases. A detailed description of the synthesis of the MOFs is provided in the supporting information.

Relative recovery from bags

As a part of the pre-experiment, we assessed the reliability of GWS containing the 10 semi-volatile target analytes (including VFAs (n = 6), phenols (n = 2), and indoles (n = 2)) by comparing changes in their sensitivity, i.e., their calibration response factors (RF) (ng−1) derived from both liquid (LWS) and gaseous (GWS) standards (Fig. 1A). The gas phase recoveries of LWS were calculated as follows:

where relative recovery from bags, RF is the response factor (ng−1). Detailed experimental procedures and derived RR analysis results are summarized in the supplementary information in Tables S1 to S6. BT experiments were performed to assess the competitive adsorption capacity of the three synthesized MOFs for the mixture of 14 target analytes (Fig. 1B).

Prior to the breakthrough experiments, the MOFs were treated at 100 °C for 1 h under a nitrogen purge at 100 mL min−1 to remove the possible contaminants. A gaseous mixture containing low-ppb target compounds at 1 atm was pulled through the sorbent bed (89 mm length, 4 mm id, and 6 mm in od) packed with 0.4 mg of a given MOF using a purge flow rate of 200 mL min−1. The inlet concentration of the VOC (Cin) was ~100 ppb (Table S9). The effluent gas stream was sampled using a three-bed (Carbopack C, B, and X) sorbent tube (ST) at 5 min intervals for ST/thermal desorption/gas chromatography/mass spectrometric (ST/TD/GC/MS) analysis to determine the outlet VOC concentration (Cout).

Comparison of sorptive capacity between MOFs and commercial adsorbents

To date, there is a dearth of data on MOF sorption performance for various gaseous species, especially SVOCs. To learn more about the adsorption behavior of VOCs on MOF, we conducted a series of comparative sorptive removal experiments using three MOFs (Experiment 1) and three well known commercial adsorbents as a reference (Experiment 2, Fig. 1B). The mass of all six sorbents used in the experiments was kept constant (0.4 mg) to facilitate comparisons of breakthrough concentrations, breakthrough volumes, and equilibrium adsorption capacity. Detailed descriptions of the experimental setup (Experiment 1 and 2) are provided in the supplementary information.

Density functional theory (DFT)

The interactions between the MOF and the guest molecules were studied using DFT calculations. The pseudo-potential code SIESTA59 model was applied for this purpose. All calculations were conducted using the generalized gradient approximation (GGA-PBE) with spin-polarization60 by taking into account the +vdw correction61 which is required for describing weak interactions. Full optimization of atomic positions was performed. During the optimization, the ion cores are described by norm-conserving non-relativistic pseudo-potentials62 with cut-off radii of 2.43, 2.25, 1.15, 1.14, 1.45, and 1.25 au for Zn, Cu, O, C, N and H, respectively. The wave functions were expanded with a double-ζ plus polarization basis of localized orbitals for all species excluding hydrogen. Optimization of the force and total energy was performed with an accuracy of 0.04 eV/Å and 1 meV, respectively. All calculations were carried out with an energy mesh cut-off of 300 Ry and a k-point mesh of 4 × 4 × 4 in the Mokhorst-Park scheme63. The calculation was conducted for realistic atomic structures of MOF-5 and MOF-199 taken from the Cambridge Database (CCDC). The DFT-based 0 K change in adsorption enthalpy (ΔHad) was calculated by

Here, Ehost+guest is the total energy of MOF with adsorbed guest molecules, Ehost is the total energy of the pure MOF, and Eguest is the energy of the guest molecule in the gas-phase. The adsorption Gibbs free energy (ΔGad at 298 K) was calculated using the 0 K ΔHad (with no thermal and zero-point energy corrections) and the estimated adsorption entropy change (ΔSad) by following the empirical procedure of Campbell and Sellers64,

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Vellingiri, K. et al. Metal organic frameworks as sorption media for volatile and semi-volatile organic compounds at ambient conditions. Sci. Rep. 6, 27813; doi: 10.1038/srep27813 (2016).

References

Barea, E., Montoro, C. & Navarro, J. A. Toxic gas removal–metal–organic frameworks for the capture and degradation of toxic gases and vapours. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 5419–5430 (2014).

DeCoste, J. B. & Peterson, G. W. Metal–organic frameworks for air purification of toxic chemicals. Chem. Rev. 114, 5695–5727 (2014).

Kumar, P., Paul, A. & Deep, A. Sensitive chemosensing of nitro group containing organophosphate pesticides with MOF-5. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 195, 60–66 (2014).

Kim, K.-H., Jahan, S. A. & Kabir, E. A review on human health perspective of air pollution with respect to allergies and asthma. Environ. Int. 59, 41–52 (2013).

Ni, J.-Q. Research and demonstration to improve air quality for the US animal feeding operations in the 21st century–A critical review. Environ. Pollut. 200, 105–119 (2015).

Lim, T.-T., Jin, Y., Ni, J.-Q. & Heber, A. J. Field evaluation of biofilters in reducing aerial pollutant emissions from a commercial pig finishing building. Biosyst. Eng. 112, 192–201 (2012).

Britt, D., Tranchemontagne, D. & Yaghi, O. M. Metal-organic frameworks with high capacity and selectivity for harmful gases. P. Natl. A. Sci. 105, 11623–11627 (2008).

Falcaro, P. et al. MOF positioning technology and device fabrication. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 5513–5560 (2014).

Demessence, A., D’Alessandro, D. M., Foo, M. L. & Long, J. R. Strong CO2 binding in a water-stable, triazolate-bridged metal–organic framework functionalized with ethylenediamine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 8784–8786 (2009).

Lee, W. R. et al. Diamine-functionalized metal–organic framework: Exceptionally high CO2 capacities from ambient air and flue gas, ultrafast CO2 uptake rate, and adsorption mechanism. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 744–751 (2014).

McDonald, T. M., D’Alessandro, D. M., Krishna, R. & Long, J. R. Enhanced carbon dioxide capture upon incorporation of N, N′-dimethylethylenediamine in the metal–organic framework CuBTTri. Chem. Sci. 2, 2022–2028 (2011).

McDonald, T. M. et al. Capture of carbon dioxide from air and flue gas in the alkylamine-appended metal–organic framework mmen-Mg2 (dobpdc). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 7056–7065 (2012).

McDonald, T. M. et al. Cooperative insertion of CO2 in diamine-appended metal-organic frameworks. Nature 519, 303–308 (2015).

Zhao, Z. et al. Competitive adsorption and selectivity of benzene and water vapor on the microporous metal organic frameworks (HKUST-1). Chem. Eng. J. 259, 79–89 (2015).

He, W. W. et al. Phenyl groups result in the highest benzene storage and most efficient desulfurization in a series of isostructural metal–organic frameworks. Chem. A. Euro. J. 21, 9784–9789 (2015).

Huang, C.-Y., Song, M., Gu, Z.-Y., Wang, H.-F. & Yan, X.-P. Probing the adsorption characteristic of metal–organic framework MIL-101 for volatile organic compounds by quartz crystal microbalance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 4490–4496 (2011).

Zhao, Z., Li, X. & Li, Z. Adsorption equilibrium and kinetics of p-xylene on chromium-based metal organic framework MIL-101. Chem. Eng. J. 173, 150–157 (2011).

Ahmed, I. & Jhung, S. H. Effective adsorptive removal of indole from model fuel using a metal-organic framework functionalized with amino groups. J. Hazard. Mater. 283, 544–550 (2015).

Liu, B., Yang, F., Zou, Y. & Peng, Y. Adsorption of phenol and p-nitrophenol from aqueous solutions on metal–organic frameworks: Effect of hydrogen bonding. J. Chem. Eng. Data 59, 1476–1482 (2014).

Yang, K., Xue, F., Sun, Q., Yue, R. & Lin, D. Adsorption of volatile organic compounds by metal-organic frameworks MOF-177. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 1, 713–718 (2013).

Qin, W., Silvestre, M. E., Kirschhöfer, F., Brenner-Weiss, G. & Franzreb, M. Insights into chromatographic separation using core–shell metal–organic frameworks: Size exclusion and polarity effects. J. Chromatogr. A 1411, 77–83 (2015).

Qin, W., Cao, W., Liu, H., Li, Z. & Li, Y. Metal–organic framework MIL-101 doped with palladium for toluene adsorption and hydrogen storage. RSC Adv. 4, 2414–2420 (2014).

Trens, P. et al. Adsorption and separation of xylene isomers vapors onto the chromium terephthalate-based porous material MIL-101 (Cr): An experimental and computational study. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 183, 17–22 (2014).

Sun, X., Xia, Q., Zhao, Z., Li, Y. & Li, Z. Synthesis and adsorption performance of MIL-101 (Cr)/graphite oxide composites with high capacities of n-hexane. Chem. Eng. J. 239, 226–232 (2014).

Van de Voorde, B. et al. N/S-heterocyclic contaminant removal from fuels by the mesoporous metal–organic framework MIL-100: The role of the metal ion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 9849–9856 (2013).

Ahmed, I. & Jhung, S. H. Adsorptive denitrogenation of model fuel with CuCl-loaded metal–organic frameworks (MOFs). Chem. Eng. J. 251, 35–42 (2014).

Ahmed, I., Khan, N. A., Hasan, Z. & Jhung, S. H. Adsorptive denitrogenation of model fuels with porous metal-organic framework (MOF) MIL-101 impregnated with phosphotungstic acid: Effect of acid site inclusion. J. Hazard. Mater. 250, 37–44 (2013).

Ahmed, I., Hasan, Z., Khan, N. A. & Jhung, S. H. Adsorptive denitrogenation of model fuels with porous metal-organic frameworks (MOFs): Effect of acidity and basicity of MOFs. Appl. Catal., B 129, 123–129 (2013).

Stavert, J. R., Drayton, B. A., Beggs, J. R. & Gaskett, A. C. The volatile organic compounds of introduced and native dung and carrion and their role in dung beetle foraging behaviour. Ecol. Entomol. 39, 556–565 (2014).

Sharma, N., Doerner, K., Alok, P. & Choudhary, M. Skatole remediation potential of Rhodopseudomonas palustris WKU‐KDNS3 isolated from an animal waste lagoon. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 60, 298–306 (2015).

Jo, S.-H. et al. Odor characterization from barns and slurry treatment facilities at a commercial swine facility in South Korea. Atmos. Environ. 119, 339–347 (2015).

Lin, J. et al. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of volatile constituents from latrines. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 7876–7882 (2013).

Iqbal, M. A., Kim, K.-H., Szulejko, J. E. & Cho, J. An assessment of the liquid–gas partitioning behavior of major wastewater odorants using two comparative experimental approaches: Liquid sample-based vaporization vs. impinger-based dynamic headspace extraction into sorbent tubes. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 406, 643–655 (2014).

Gu, Z.-Y., Yang, C.-X., Chang, N. & Yan, X.-P. Metal–organic frameworks for analytical chemistry: From sample collection to chromatographic separation. Acc. Chem. Res. 45, 734–745 (2012).

Gu, Z.-Y., Wang, G. & Yan, X.-P. MOF-5 metal–organic framework as sorbent for in-field sampling and preconcentration in combination with thermal desorption GC/MS for determination of atmospheric formaldehyde. Anal. Chem. 82, 1365–1370 (2010).

Kim, Y.-H. & Kim, K.-H. Test on the reliability of gastight syringes as transfer/storage media for gaseous VOC analysis: The extent of VOC sorption between the inner needle and a glass wall surface. Anal. Chem. 87, 3056–3063 (2015).

Kim, K.-H., Kim, Y.-H. & Brown, R. J. Conditions for the optimal analysis of volatile organic compounds in air with sorbent tube sampling and liquid standard calibration: Demonstration of solvent effect. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 405, 8397–8408 (2013).

Kim, K. H. & Nguyen, H. T. Effects of injection volume change on gas chromatographic sensitivity determined with two contrasting calibration approaches for volatile organic compounds. J. Sep. Sci. 30, 367–374 (2007).

Kim, Y.-H. & Kim, K.-H. Extent of sample loss on the sampling device and the resulting experimental biases when collecting volatile fatty acids (VFAs) in air using sorbent tubes. Anal. Chem. 85, 7818–7825 (2013).

Koziel, J. A. et al. Evaluation of sample recovery of malodorous livestock gases from air sampling bags, solid-phase microextraction fibers, Tenax TA sorbent tubes, and sampling canisters. J. Air Waste Manage. Assoc. 55, 1147–1157 (2005).

Szulejko, J. E., Kim, Y. H. & Kim, K. H. Method to predict gas chromatographic response factors for the trace‐level analysis of volatile organic compounds based on the effective carbon number concept. J. Sep. Sci. 36, 3356–3365 (2013).

Trabue, S. L., Anhalt, J. C. & Zahn, J. A. Bias of Tedlar bags in the measurement of agricultural odorants. J. Environ. Qual. 35, 1668–1677 (2006).

Wu, C.-M., Rathi, M., Ahrenkiel, S. P., Koodali, R. T. & Wang, Z. Facile synthesis of MOF-5 confined in SBA-15 hybrid material with enhanced hydrostability. Chem. Commun. 49, 1223–1225 (2013).

Sharma, A., Kaur, S., Mahajan, C., Tripathi, S. & Saini, G. Fourier transform infrared spectral study of N, N′-dimethylformamide-water-rhodamine 6G mixture. Mol. Phys. 105, 117–123 (2007).

Hao, J.-N. & Yan, B. Amino-decorated lanthanide (III) organic extended frameworks for multi-color luminescence and fluorescence sensing. J. Mater. Chem. C 2, 6758–6764 (2014).

Xu, B. et al. Solvothermal synthesis of luminescent Eu(BTC) (H2O) DMF hierarchical architectures. Cryst. Eng. Comm. 14, 2914–2919 (2012).

Li, Y. et al. Removal of sulfur compounds by a copper-based metal organic framework under ambient conditions. Energy Fuels 29, 298–304 (2014).

Zhang, Q. et al. A porous metal–organic framework with –COOH groups for highly efficient pollutant removal. Chem. Commun. 50, 14455–14458 (2014).

Raoof, J.-B., Hosseini, S. R., Ojani, R. & Mandegarzad, S. MOF-derived Cu/nanoporous carbon composite and its application for electro-catalysis of hydrogen evolution reaction. Energy (2015).

Xiang, Z. et al. Facile preparation of high-capacity hydrogen storage metal-organic frameworks: A combination of microwave-assisted solvothermal synthesis and supercritical activation. Chem. Eng. Sci. 65, 3140–3146 (2010).

Choi, J. R., Tachikawa, T., Fujitsuka, M. & Majima, T. Europium-based metal–organic framework as a photocatalyst for the one-electron oxidation of organic compounds. Langmuir 26, 10437–10443 (2010).

Millward, A. R. & Yaghi, O. M. Metal-organic frameworks with exceptionally high capacity for storage of carbon dioxide at room temperature. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 17998–17999 (2005).

Woolfenden, E. Sorbent-based sampling methods for volatile and semi-volatile organic compounds in air: Part 1: Sorbent-based air monitoring options. J. Chromatogr. A 1217, 2674–2684 (2010).

Kim, Y.-H. & Kim, K.-H. A simple methodological validation of the gas/particle fractionation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in ambient air. Sci. Rep. 5 (2015).

Kim, Y.-H., Kim, K.-H., Szulejko, J. E. & Parker, D. Development of the detection threshold concept from a close look at sorption occurrence inside a glass vial based on the in-vial vaporization of semivolatile fatty acids. Anal. Chem. 86, 6640–6647 (2014).

Lahoz-Martín, F. D., Martín-Calvo, A. & Calero, S. Selective separation of BTEX mixtures using metal–organic frameworks. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 13126–13136 (2014).

Yang, K., Sun, Q., Xue, F. & Lin, D. Adsorption of volatile organic compounds by metal–organic frameworks MIL-101: Influence of molecular size and shape. J. Hazard. Mater. 195, 124–131 (2011).

Ferreira, A. F. P. et al. Suitability of Cu-BTC extrudates for propane–propylene separation by adsorption processes. Chem. Eng. J. 167, 1–12 (2011).

Soler, J. M. et al. The SIESTA method for ab initio order-N materials simulation. J. Phy. Cond. Mat. 14, 2745 (2002).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Román-Pérez, G. & Soler, J. M. Efficient implementation of a van der Waals density functional: Application to double-wall carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 096102 (2009).

Troullier, N. & Martins, J. L. Efficient pseudopotentials for plane-wave calculations. Phys. Rev. B 43, 1993 (1991).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188 (1976).

Campbell, C. T. & Sellers, J. R. The entropies of adsorbed molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 18109–18115 (2012).

Nagata, Y. & Takeuchi, N. Measurement of odor threshold by triangle odor bag method. Odor Measurement Review, Office of Odor, Noise and Vibration Environmental Management Bureau, Ministry of the Environment, Government of Japan, Tokyo, Japan, 118–127 (2003).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (MEST) (No. 2009-0093848). E Kwon also acknowledges the support made by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) Grant funded by the Korean Government (MSIP) (No. 2914RA1A004893). The third author thanks SERB-DST, New Delhi for ‘Young Scientist-Start up Research Grant (YSS/2015/001440).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.V., J.E.S., P.K., E.E.K., K.-H.K., A.D. and R.J.C.B. participated in preparing the main manuscript text and all tables and figures. K.V. carried out all major experimental tasks. D.W.B. conducted the DFT computation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Vellingiri, K., Szulejko, J., Kumar, P. et al. Metal organic frameworks as sorption media for volatile and semi-volatile organic compounds at ambient conditions. Sci Rep 6, 27813 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep27813

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep27813

This article is cited by

-

A review on metal-organic framework hybrid-based flexible electrodes for solid-state supercapacitors

Ionics (2023)

-

Adsorption Behavior of Multi-Component BTEX on the Synthesized Green Adsorbents Derived from Abelmoschus esculentus L. Waste Residue

Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology (2023)

-

Transition metal-based metal–organic frameworks for environmental applications: a review

Environmental Chemistry Letters (2021)

-

Influence of the porous structure and functionality of the MIL type metal-organic frameworks and carbon matrices on the adsorption of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid

Russian Chemical Bulletin (2021)

-

Insight into Fluorocarbon Adsorption in Metal-Organic Frameworks via Experiments and Molecular Simulations

Scientific Reports (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.