Abstract

Emergent extreme events are a key characteristic of complex dynamical systems. The main tool for detailed and deep understanding of their stochastic dynamics is the statistics of time intervals of extreme events. Analyzing extensive experimental data, we demonstrate that for the velocity time series of fully-developed turbulent flows, generated by (i) a regular grid; (ii) a cylinder; (iii) a free jet of helium, and (iv) a free jet of air with the Taylor Reynolds numbers Reλ from 166 to 893, the interoccurrence time distributions P(τ) above a positive threshold Q in the inertial range is described by a universal q- exponential function, P(τ) = β(2 − q)[1 − β(1 − q)τ]1/(1−q), which may be due to the superstatistical nature of the occurrence of extreme events. Our analysis provides a universal description of extreme events in turbulent flows.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dynamical systems in biology, physics, chemistry, computer science, social and other types of networks, and many other fields and phenomena exhibit rich and complex behavior that are not amenable to the classical methods of analysis. Although there is no consensus on what constitutes complex systems, they are usually referred to as such because they typically consist of many subparts that interact with each other over many length and/or time scales, not uniquely but in several ways. Due to their complexity, the difficulty in precisely describing their behavior and properties, and the ubiquity of complex dynamical systems in nature, one approach to the analysis of such systems has been based on trying to identify their universal features. That is, one tries to discover whether there are certain features of complex dynamical systems that are exhibited by a large class of them, regardless of the details of their structure. If such universal features can be identified, then one can utilize them to develop the simplest model of such systems that exhibit the universal properties and utilize it to gain further insights into their dynamics.

One of the main features of experimental data for complex dynamical systems is their small time scale intermittency. Intuitively, intermittency represents the strongly correlated fluctuations that lead to deviations of increments probability distribution functions (PDF) from Gaussian statistics at small scales and is defined by, δxr = x(t + r) − x(t), for a given small r. The stretched exponential like behavior of P(δxr) changes as the scale r increases from the smallest to the largest ones.

A prototype of complex dynamical systems is turbulent flow. As is well understood, any flow field is the result of the competition between two factors, namely, the inertial and viscous forces1. The Taylor Reynolds numbers is defined as Reλ = Urmsλ/ν, where Urms, λ, and ν are, respectively, the root mean-square of the fluctuations in the velocity field, the Taylor length scale of the flow field, and the kinematic viscosity2. In turbulent flows, which correspond to large Reλ, i.e. the dominance of inertial over viscous forces, the fluid particles follow complex trajectories resembling stochastic motion. The flow is characterized by an energy flux cascade from a large integral scale L towards the intermediate and eventually smallest scales in which energy is dissipated by molecular viscosity. The inertial range is defined by the scales λ < l < L.

Traditionally, the universality in fully-developed turbulence is expressed in terms of the multiscaling exponents that describe the multiscaling of the positive ordered structure functions of the velocity increments in the inertial range under the steady state condition. More precisely, the longitudinal velocity increments,  , across a distance r (in the inertial range) is believed to behave as,

, across a distance r (in the inertial range) is believed to behave as,  , where ζ(n) is the scaling exponent. Here, the field v(x) is the velocity at location x. The Kolmogorov’s K41 theory3 predicts that, ζ(n) = n/3, but various experimental as well as numerical studies have indicated significant deviations of ζ(n) from n/3. Such deviations are referred to as anomalous scaling, and are due to the small-scale intermittent nature of fully-developed turbulence1. Many phenomenological models have been proposed4,5,6,7,8,9 to study the anomalous scaling.

, where ζ(n) is the scaling exponent. Here, the field v(x) is the velocity at location x. The Kolmogorov’s K41 theory3 predicts that, ζ(n) = n/3, but various experimental as well as numerical studies have indicated significant deviations of ζ(n) from n/3. Such deviations are referred to as anomalous scaling, and are due to the small-scale intermittent nature of fully-developed turbulence1. Many phenomenological models have been proposed4,5,6,7,8,9 to study the anomalous scaling.

Turbulent flow is also a system in which the motion of the fluid particles manifests complex fluctuations and possesses many universal features10,11,12,13,14,15. For example, the anomalous scaling exponents ζ(n) display16,17,18 universality with respect to the boundary conditions and the large-scale forcing mechanisms of fluid flow. Understanding how the complexity of turbulent flow, as a strongly complex non-equilibrium phenomenon with nonlinear memory, can be described by universal laws has been a great scientific challenge for decades.

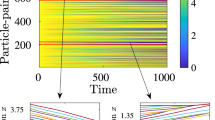

On the other hand to gain deeper understanding of the stochastic dynamics of the velocity time series, one can study the statistics of time intervals of extreme events. It has been shown in recent years19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32 that the analysis of the interoccurrence time (IOT) series is a powerful tool for characterizing temporal properties of extreme events, the main cause of complexity in such systems. Let us introduces a positive/negative threshold Q and search for possible information inherent in the statistics of the time intervals τi between successive events above/below the threshold, as shown in Fig. 1, in order to identify the laws that govern the occurrence of the extreme events. In other words, the IOT series represent the reoccurrence of events that exceed a certain threshold or level Q, such that for larger values of Q the events are rare or extreme28,29,30. For uncorrelated processes, the PDF of τi is exponential,  , where

, where  is the mean IOT for a given threshold Q, and the corresponding IOT sequence is also uncorrelated.

is the mean IOT for a given threshold Q, and the corresponding IOT sequence is also uncorrelated.

An empirical study indicated31,33 that, for a fixed mean time interval  and a negative threshold Q, the distribution P(τ) of the IOT between the losses in a financial market below Q is described, for large ranges of time scales, by a universal q-exponentials given by,

and a negative threshold Q, the distribution P(τ) of the IOT between the losses in a financial market below Q is described, for large ranges of time scales, by a universal q-exponentials given by,

and the IOTs τi are also long-range correlated32. Here, A = β(2 − q) is a normalization factor. The question that arises is whether Eq. (1) is more general, and can describe extreme events in other complex dynamical systems.

In this paper we analyze the statistics of extreme events of fully-developed turbulent flows over a wide range of Reynolds numbers with distinct mechanisms of generation of turbulence, by analyzing the IOTs above a positive threshold Q. We analyze extensive experimental data for the velocity time series of turbulent flows generated by, (i) a regular grid; (ii) a cylinder; (iii) a free jet in helium34, and (iv) a free jet in air with Reynolds numbers Reλ ranging from 166 to 893. We compute the statistics of the IOTs τi of the normalised velocity time series v(t) above a positive threshold Q. For given Q, the IOTs have mean and variance  and σQ, respectively. We demonstrate that the temporal occurrence of the extreme events of turbulent flows is characterized by a universal function over a wide range of τ that belong to the inertial range. We find, for τ values that are longer than the integral scale, that the IOT statistics has nonuniversal exponential type behaviour. We also show that the q-exponential form of the PDF of the IOT statistics may be due to the superstatistical nature of the occurrence of extreme events.

and σQ, respectively. We demonstrate that the temporal occurrence of the extreme events of turbulent flows is characterized by a universal function over a wide range of τ that belong to the inertial range. We find, for τ values that are longer than the integral scale, that the IOT statistics has nonuniversal exponential type behaviour. We also show that the q-exponential form of the PDF of the IOT statistics may be due to the superstatistical nature of the occurrence of extreme events.

Results

In Fig. 2(a) we present the computed IOT distributions P(τ) corresponding to the velocity time series v(t), measured for six Reynolds numbers and calculated for various σQ (or various thresholds Q). The plots are in logarithmic scales and have been shifted for better clarity. All the curves display a universal behavior in the inertial range in which the range increases for large Reλ. The inertial range in terms of τ/σQ, such as for example for σQ = 32, is the interval 0.8–37. To determine the inertial range in each time series we calculate the Taylor and integral time scales. Such a behavior in the inertial range is modeled by the q-exponentials of Eq. (1). The dashed lines in Fig. 2(a) indicate q-exponentials function with the parameters, β ≈ 0.35, q ≈ 1.62, and  . The dependence on the Reynolds number of β and q are shown in Fig. 2(b) for three σQ. Clearly, for large Reynolds numbers q and β approach their universal values.

. The dependence on the Reynolds number of β and q are shown in Fig. 2(b) for three σQ. Clearly, for large Reynolds numbers q and β approach their universal values.

(a) The PDF P(τ/σQ) of the IOTs for the normalized velocity time series for six Reynolds numbers Reλ. (b) Dependence of the parameters q and b on the Reynolds number. For large Reλ they approach β ≈ 0.35 and q ≈ 1.62. The associated q-exponentials, Eq. (1), with the asymptotic values of q and β are shown by dashed lines in (a).

To check the generality of such universal behavior, we analyzed the velocity time series of various high-Reynolds number turbulent flows, generated by various mechanisms, and calculated their corresponding IOT distributions P(τ). Figure 3 demonstrates the IOT distributions of 17 normalized turbulent velocity series for several Reynolds number, all of which collapse onto the same universal curve in the inertial range given by Eq. (1) with the same parameters as in Fig. 2 (dotted line). We, therefore, conclude that the extreme events statistics of turbulent flows are very well characterized by a universal q-exponential function for the τs that belong to the inertial range. Note that, as shown in the inset of Fig. 3, for the τs that are outside of the inertial range, the PDFs of the IOT approach a simple nonuniversal exponential function. For small τ, on the other hand, the structure of the PDFs is caused by Taylor time scale.

Dotted line shows the q-exponential function, Eq. (1), with β ≈ 0.35 and q ≈ 1.62. The inertial range in terms of τ/σQ with σQ = 32 is the interval 0.8–37. The PDFs of the large IOTs, which are outside the inertial range, are shown in a semi-logarithmic plot in the inset in which the linear dashed lines indicate the nonuniversal exponential decay.

It should also be noted that, for each time series, there is a one-to-one correspondence between Q and  or σQ. We present in Fig. 4 the dependence on the threshold Q of

or σQ. We present in Fig. 4 the dependence on the threshold Q of  and σQ for the normalized velocity series in several turbulent flows. All the curves can be represented by, for example, the functional forms

and σQ for the normalized velocity series in several turbulent flows. All the curves can be represented by, for example, the functional forms  and σQ = σ0 exp (0.05Q3 + 1.25Q), where

and σQ = σ0 exp (0.05Q3 + 1.25Q), where  and σ0 = σQ=0.

and σ0 = σQ=0.

The Q dependence of (a)  , and (b) σQ of the normalized velocity time series and several Reynolds numbers. The dashed lines in (a,b) indicate the functional form,

, and (b) σQ of the normalized velocity time series and several Reynolds numbers. The dashed lines in (a,b) indicate the functional form,  and σQ = σ0 exp(0.05Q3 + 1.25Q), respectively. Symbols are the same as in Fig. 3.

and σQ = σ0 exp(0.05Q3 + 1.25Q), respectively. Symbols are the same as in Fig. 3.

To check the effect of the correlation structure of the velocity time series on the IOT statistics, we shuffled the velocity time series and calculated the PDF of the resulting series. The results are shown in Fig. 5(a) for a Reynolds number of 603 and five values of σQ. All the curves collapse onto the same exponential function,  . We note further that, the heavy tails of the PDF have no effect on the IOT statistics, since the time intervals between extreme events are studied, and the IOT statistics depend solely on the positions of such events.

. We note further that, the heavy tails of the PDF have no effect on the IOT statistics, since the time intervals between extreme events are studied, and the IOT statistics depend solely on the positions of such events.

(a) The PDF of the normalized IOTs for the shuffled velocity time series with Reλ = 603, and several standard deviations σQ. All the data collapse onto the same exponential function,  . (b) The rescaled PDFs of the IOTs extracted from the fBm processes with various Hurst exponents, indicating a power-law form,

. (b) The rescaled PDFs of the IOTs extracted from the fBm processes with various Hurst exponents, indicating a power-law form,  . (c) The PDFs of the IOT of the velocity time series with Reλ = 603, and that of a fBm process with H = 0.38, for several standard deviations. (d) The probability density u(b) for the normalized IOT sequences associated with the normalised velocity time series for Reλ = 603 (circles) and its corresponding shuffled series (diamonds). Dashed line indicates the fitted χ2 distribution, Eq. (3), with a degree of freedom k ≃ 12.

. (c) The PDFs of the IOT of the velocity time series with Reλ = 603, and that of a fBm process with H = 0.38, for several standard deviations. (d) The probability density u(b) for the normalized IOT sequences associated with the normalised velocity time series for Reλ = 603 (circles) and its corresponding shuffled series (diamonds). Dashed line indicates the fitted χ2 distribution, Eq. (3), with a degree of freedom k ≃ 12.

To investigate the influence of the nonlinear nature of the velocity time series on PDFs of the IOT, we used the fractional Brownian motion (fBm), a centered self-affine Gaussian process that possesses linear long memory and is characterized by the Hurst exponent35 H ∈ (0, 1). H is defined by, 〈[x(t + l) − x(t)]2〉 = cHl2H, where cH is a H-dependent constant. The fBm was introduced by Kolmogorov36 in connection with his work related to turbulence, and studied extensively later on by Mandelbrot and van Ness37. We note that the velocity time series in turbulence has nonlinear exponents ζ(n) with respect to n, while fBM has linear n-dependent exponents.

Then, we generated several fBM series with various Hurst exponents, and computed the PDFs of the corresponding IOTs. In Fig. 5(b) we present a plot of τ2−HP(τ) versus τ for various Hurst exponents. All the curves collapse onto a straight horizontal line, indicating a power-law behavior of the form,  , for the PDFs of the IOT of the fBM processes. Figure 5(c) presents the PDF of the IOT of the normalized velocity series for a Reynolds number of 603 and its linear corresponding fBM series with Hurst exponent of H ≈ 0.38, computed by detrended fluctuation analysis38. They are compared with synthetic fBM process with several σQ. We can conclude that, the existence of any difference between the PDF of the IOT of the velocity time series and that of the fBM series can be due to the presence of the nonlinear correlation effects and influence of characteristic time scales λ and L in velocity time series.

, for the PDFs of the IOT of the fBM processes. Figure 5(c) presents the PDF of the IOT of the normalized velocity series for a Reynolds number of 603 and its linear corresponding fBM series with Hurst exponent of H ≈ 0.38, computed by detrended fluctuation analysis38. They are compared with synthetic fBM process with several σQ. We can conclude that, the existence of any difference between the PDF of the IOT of the velocity time series and that of the fBM series can be due to the presence of the nonlinear correlation effects and influence of characteristic time scales λ and L in velocity time series.

To connect the parameters of the IOT statistics that we identify in this paper to the Kolmogorov exponent ζ(2), we note that in the limit  the IOT statistics is written as a power law,

the IOT statistics is written as a power law,  . On the other hand, in the linear approximation we also showed that

. On the other hand, in the linear approximation we also showed that  . Thus, equating the two expressions yields, q = (3 − H)/(2 − H). The estimate, q ≈ 1.62 then yields, H ≈ 0.38, in complete agreement with the estimate reported for isotropic and homogeneous turbulence39. Note also that, the Hurst exponent is related to ζ(n) by H = ζ(n = 2)/2, hence establishing a direct relation between the Kolmogorov exponent and parameter q in the q-exponential function.

. Thus, equating the two expressions yields, q = (3 − H)/(2 − H). The estimate, q ≈ 1.62 then yields, H ≈ 0.38, in complete agreement with the estimate reported for isotropic and homogeneous turbulence39. Note also that, the Hurst exponent is related to ζ(n) by H = ζ(n = 2)/2, hence establishing a direct relation between the Kolmogorov exponent and parameter q in the q-exponential function.

Further insight is gained by recognizing, as pointed out earlier, that the IOT distribution associated with an uncorrelated process is a simple exponential function, P(τ) ~ exp(−bτ), with b = 1/σQ. Most IOTs are very sharp for large values of b (σQ), whereas small values of b correspond to frequent occurrence of long IOTs. The existence of correlations in the process makes b a random variable with a probability density u(b). Then40,

where the multiplier b in the integrand is a normalization factor. It is then clear that any deviation of u(b) from a delta function yields a nonexponential P(τ). It has been shown41,42 that if b is χ2-distributed, one obtains the q-exponential form of P(τ). Simply put, if {xi} represents a set of independent Gaussian variables xi, then  is distributed according to the χ2 distribution with k degrees of freedom, and

is distributed according to the χ2 distribution with k degrees of freedom, and

with b0 being a constant. To compute the distribution of b, one divides the normalized IOT sequences into a large number of equal windows with a size larger than the integral scale, estimates b = 1/σQ for each window, and constructs their distribution.

Thus, we constructed u(b) for the velocity times series with Reλ = 603, as well as for its shuffled series. In Fig. 5(d) we present u(b) for the two series, along with their fit to the χ2 distribution. The velocity time series is well-represented by the χ2 distribution with k = 12, whereas its shuffled series tends to a delta function corresponding to k → ∞. Thus, the q-exponential form of the PDF of the IOT statistics may be due to the superstatistical nature of the occurrence of extreme events.

Summary

It is well-known that the dynamics of many complex systems is characterized by the same universal principles, including high affinity for self-organization, pattern formation and synchronization that often generate extreme events. Turbulence is a prototype of such complex systems, as it possesses strong extreme events over small length (time) scales. Through extensive analyzes of the time series for fully-developed turbulent flows over a broad range of the Reynolds number and generated by various mechanisms, we have shown that above a positive threshold Q the probability distributions of the interoccurrence times of the velocity time series in the inertial range are well characterized and represented by the same (universal) q-exponentials function, PQ(τ) = β(2 − q)[1 + β(q − 1)τ]1/(1−q), with β ≈ 0.35 and q ≈ 1.62. We also showed that the q-exponential form of the PDFs of the IOT may be due to the superstatistical nature of the occurrence of extreme events. Due to large relative distances between the sources of generating turbulence and the points of measurements, it was assumed in our analysis that turbulence is isotropic. A study of the role of anisotropy in statistical properties of the IOT series and study the relation between the exponents ζ(n) and the IOT of the velocity increments will be the next step in this research direction.

We believe that our method of analysis is applicable to other complex systems and phenomena in which extreme events occur, and yields valuable information for risk analysis and understanding of such events in complex dynamical systems43.

Experimental Methodology

Large data sets of turbulent flows with Taylor Reynolds number Reλ ranging from 166 to 893 were analyzed. The turbulent flows were generated by various mechanisms. The data correspond to four subclasses of data for which turbulence was generated by, (i) a regular grid44; (ii) a cylinder44; (iii) a free jet of low-temperature helium45, and (iv) a free jet of air46.

In the cases of (i) and (ii), measurements with a regular grid and in a cylinder’s wake were carried in the wind tunnel of the University of Erlangen, Germany44. The regular grid has a mesh width of size M = 0.05 m. The wake data were recorded at a downstream position of x = 32 m. The data generated by the cylinder’s wake were recorded at a downstream position of x = 40D, with the cylinder’s diameters being D = 0.02 m and 0.05 m.

In the (iii) case helium free-jet experiments were performed at CNRS, Grenoble, France45. They were carried out under cryogenic conditions in which the helium has very low viscosity and its free jet reaches high Reynolds numbers. The distance between the nozzle and the position of the measurement was x = 40N, where the nozzle’s diameter was N = 0.002 m.

In the (iv) case, the free-jet data in air were measured with two experimental setups at the University of Oldenburg, Germany. The first setup used was a closed chamber (1 × 1 × 2 m3 corresponding to width × width × downstreamlength) in which air was injected by means of a nozzle with a diameter of N = 0.008 m. The data for the free-jet turbulence were measured at x = 40 N. A second set of experiments was carried out with a freely-injected jet in the laboratory, where the distance between the free jet and the walls was on the order of 2 m. Therefore, the free jet stayed centered downstream and the measurements exhibited no bending of the jet. Measurements were carried out at x = 40 N, 60 N and 80 N, where the nozzle’s outlet was N = 0.1 m.

For all the measurements, the isotropy of turbulence was achieved due to the large relative distances between the points of generating turbulence and the points at which the measurements were carried out. Each dataset contained 1.25 × 106 to 40 × 106 samples of the longitudinal velocity. Almost all the measurements were performed with the hot-wire technique (mostly single wire), except45 those in which a microstructured hot-point probe was used. It is worth pointing out that all the experiments and the corresponding measurements were performed in such a way that the corresponding datasets contained high-quality data in terms of, e.g. the downstream position, the probe size, the length of the data log, and the sampling frequency. More information on the experiments and the datasets are given in the cited references. Table 1 lists the Reynolds numbers for the data sets used in Fig. 3.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Manshour, P. et al. Interoccurrence time statistics in fully-developed turbulence. Sci. Rep. 6, 27452; doi: 10.1038/srep27452 (2016).

Change history

01 September 2016

A correction has been published and is appended to both the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has been fixed in the paper.

References

Frisch, U. Turbulence: The Legacy of AN Kolmogorov (Cambridge University Press, 1995).

Reynolds, O. Collected Papers on Mechanical and Physical Subjects 1881–1900, Vol. 2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Kolmogorov, A. N. The local structure of turbulence in incompressible viscous fluid for very large Reynolds number. C. R. Acad. Sci. URSS 30, 301–305 (1941).

Kolmogorov, A. N. A refinement of previous hypotheses concerning the local structure of turbulence in a viscous incompressible fluid at high Reynolds number. J. Fluid Mech. 13, 82–85 (1962).

Anselmet, F., Gagne, Y., Hopfinger, E. J. & Antonia, R. A. High-order velocity structure functions in turbulent shear flows. J. Fluid Mech. 140, 63–89 (1984).

Vincent, A. & Meneguzzi, M. The spatial structure and statistical properties of homogeneous turbulence. J. Fluid Mech. 225, 1–25 (1991).

Biferale, L. et al. Lagrangian statistics in fully developed turbulence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 064502 (2004).

Nelkin, M. Multifractal scaling of velocity derivatives in turbulence. Phys. Rev. A 42, 7226–7229 (1990).

Friedrich, R., Peinke, J., Sahimi, M. & Rahimi Tabar, M. R. Approaching complexity by stochastic methods: From biological systems to turbulence. Phys. Rep. 506, 87–162 (2011).

Stanley, H. E. Scaling, universality, and renormalization: Three pillars of modern critical phenomena. Rev. Mod. Phys. 71, S358–S364 (1999).

Nelkin, M. Universality and scaling in fully developed turbulence. Adv. Phys. 43, 143–181 (1994).

Grossmann, S. & Lohse, D. Universality in fully developed turbulence. Phys. Rev. E 50, 2784–2789 (1994).

She, Z.-S. & Lévêque, E. Universal scaling laws in fully developed turbulence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 72, 336–339 (1994).

Ishihara, T., Gotoh, T. & Kaneda, Y. Study of high-Reynolds number isotropic turbulence by direct numerical simulation. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 41, 165–180 (2009).

Schumacher, J. et al. Small-scale universality in fluid turbulence. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 10961–10965 (2014).

Arneodo, A. et al. Reynolds number between 30 and 5000, using extended self-similarity. Europhys. lett. 34, 411–416 (1996).

Sreenivasan, K. R. & Antonia, R. A. The phenomenology of small-scale turbulence. Ann. Rev. Fluid Mech. 29, 435–472 (1997).

Arneodo, A. et al. Universal intermittent properties of particle trajectories in highly turbulent flows. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 254504 (2008).

Bunde, A., Eichner, J. F., Kantelhardt, J. W. & Havlin, S.. The effect of long-term correlations on the return periods of rare events. Physica A 330 1–7 (2003).

Santhanam, M. S. & Kantz, H. Long-range correlations and rare events in boundary layer wind fields. Physica A 345 713–721 (2005).

Bak, P., Christensen, K., Danon, L. & Scanlon, T. Unified scaling law for earthquakes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 109901 (2002).

Corral, A. Long-term clustering, scaling, and universality in the temporal occurrence of earthquakes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 108501 (2004).

Scafetta, N. & West, B. J. Multi-scaling comparative analysis of time series and a discussion on earthquake conversations in California. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 138501 (2004).

Davidsen, J. & Goltz, C. Geophys. Are seismic waiting time distributions universal? Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, L21612 (2004).

Boffetta, G., Carbone, V., Giuliani, P., Veltri, P. & Vulpiani, A. Power laws in solar flares: self-organized criticality or turbulence? Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 4662–4665 (1999).

Davidsen, J. & Schuster, H. G. Simple model for 1/f α noise. Phys. Rev. E 65, 026120 (2002).

Bogachev, M. I., Eichner, J. F. & Bunde, A. Effect of nonlinear correlations on the statistics of return intervals in multifractal data sets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 240601 (2007).

Yamasaki, K., Muchnik, L., Havlin, S., Bunde, A. & Stanley, H. E. Scaling and memory in volatility return intervals in financial markets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 9424–9430 (2005).

Bunde, A., Eichner, J. F., Kantelhardt, J. W. & Havlin, S. Long-term memory: A natural mechanism for the clustering of extreme events and anomalous residual times in climate records. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 048701 (2005).

Eichner, J. F., Kantelhardt, J. W., Bunde, A. & Havlin, S. Extreme value statistics in records with long-term persistence. Phys. Rev. E 73, 016130 (2006).

Ludescher, J., Tsallis, C. & Bunde, A. Universal behaviour of interoccurrence times between losses in financial markets: An analytical description. Europhys. Lett. 95, 68002–68006 (2011).

Ludescher, J. & Bunde, A. Universal behavior of the interoccurrence times between losses in financial markets: Independence of the time resolution. Phys. Rev. E 90, 062809 (2014).

Tsallis, C. Possible generalization of Boltzmann-Gibbs entropy. J. Stat. Phys. 52, 479 (1988).

Castaing, B., Chabaud, B., Hébral, B., Naert, A. & Peinke, J. Turbulence at helium temperature: velocity measurements. Physica B 194, 697 (1994).

Hurst, H. E. Long term storage capacity of reservoirs. Trans. Amer. Soc. Civil Eng. 116, 770–799 (1951).

Kolmogorov, A. N. Wienerschen spiralen und einige andere interessante Kurven in hilbertschen raum. Dokl. Acad. Sci. USSR 26, 115–118 (1940).

Mandelbrot, B. B. & van Ness, J. W. Fractional Brownian motions, fractional noises and applications. SIAM Rev. 10, 422–437 (1968).

Kantelhardt, J. W. et al. Multifractal detrended fluctuation analysis of nonstationary time series. Physica A 316, 87–114 (2002).

Yakhot, V. Probability density and scaling exponents of the moments of longitudinal velocity difference in strong turbulence. Phys. Rev. E 57, 1737–1751 (1998).

Beck, C. & Cohen, E. G. D. Superstatistics. Physica A 322, 267–275 (2003).

Touchette, H. & Beck, C. Asymptotics of superstatistics. Phys. Rev. E 71, 016131 (2005).

Briggsa, K. & Beck, C. Modelling train delays with q-exponential functions. Physica A 378, 498–504 (2007).

Anvari, M. et al. Suppressing the non-Gaussian statistics of renewable power from wind and solar. arXiv:1505.01638.

Lück, St. Skalenaufgelöste Experimente und statistische Analysen von turbulenten Nachlaufströmungen, PhD-Thesis, University of Oldenburg, (2002).

Chanal, O., Chabaud, B., Castaing, B. & Hébral, B. Intermittency in a turbulent low temperature gaseous helium jet. Euro. Phys. J. B 17, 309–317 (2000).

Renner, C., Peinke, J. & Friedrich, R. Experimental indications for Markov properties of small-scale turbulence. J. Fluid Mech. 433 383–409 (2001).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to J. Peinke for interesting discussions and critical comments. Work at university of southern California was supported in part by the petroleum research fund, administered by the American chemical society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.R.R.T., P.M. and M.A. designed the project. P.M., M.R.R.T., M.A. and M.S. wrote the paper. All the authors contributed to the analysis of the data and the structure of the paper. N.R. carried out the experiments with the grid turbulence.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Manshour, P., Anvari, M., Reinke, N. et al. Interoccurrence time statistics in fully-developed turbulence. Sci Rep 6, 27452 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep27452

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep27452

This article is cited by

-

Wind Power Persistence Characterized by Superstatistics

Scientific Reports (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

and σQ, respectively.

and σQ, respectively.