Abstract

Strandings of marine animals are relatively common in marine systems. However, the underlying mechanisms are poorly understood. We observed mass strandings of krill in Antarctica that appeared to be linked to the presence of glacial meltwater. Climate-induced glacial meltwater leads to an increased occurrence of suspended particles in the sea, which is known to affect the physiology of aquatic organisms. Here, we study the effect of suspended inorganic particles on krill in relation to krill mortality events observed in Potter Cove, Antarctica, between 2003 and 2012. The experimental results showed that large quantities of lithogenic particles affected krill feeding, absorption capacity and performance after only 24 h of exposure. Negative effects were related to both the threshold concentrations and the size of the suspended particles. Analysis of the stomach contents of stranded krill showed large quantities of large particles ( > 106μm3), which were most likely mobilized by glacial meltwater. Ongoing climate-induced glacial melting may impact the coastal ecosystems of Antarctica that rely on krill.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the summer of 2002, a massive stranding event of the tunicate Salpa thompsoni, and the euphausiid Euphausia superba (hereafter referred to as ‘krill’), which are key components of the Southern Ocean ecosystem, was observed in front of the Argentinean Antarctic Station Carlini (formerly known as Jubany Station) along the shore of Potter Cove (King George Island/25 de Mayo Island, South Shetland Islands, Fig. 1a)1. We suspected that high concentrations of suspended particulate material, primarily of glacial origin, may have been associated with this stranding event. Since that event, the beaches of Potter Cove have been surveyed, and repeated stranding events have been recorded (Table 1).

(a) Map showing the location of the study area in the vicinities of Potter Cove, King George/25 de Mayo Island, South Shetland Islands, Antarctica during March 2007; maps were created using Inkscape 0.48.5 (URL: https://inkscape.org/). (b) Typical glacier-originated melt-water creek carrying large amounts of particles. Credit photos: V. Fuentes.

Potter Cove is surrounded by the Fourcade Glacier to the North and the East. A detailed description of the area has been published2. The glacier has been receding at an increasing rate (up to 1 km since the 1950s3), a trend that has also been observed for other glaciers on King George Island4. Glacial retreat causes the massive discharge of sediment-laden meltwater. This discharge was observed in Potter Cove during the summer for more than 20 years2. Sediment-laden surface water plumes, called “brown waters”, originate from meltwater creeks as well as from the glacier itself (Fig. 1b). They are a common feature in the area5,6, and the transport of sediments to the sea is a natural process in coastal areas, which occurs each spring. In Maxwell Bay, sediment mass accumulation rates of up to 0.66 g cm−2 yr−1 have been documented during the last 100 years7. Due to the present warming, dramatic increases in glacial melting have resulted in a rising particle discharge via surface and sub-surface drainage. This particle discharge is recognized as a threat to coastal ecosystems8,9.

Large quantities of suspended particles affect the growth and survival of benthic filter feeders10,11 by clogging their filtration systems8. In copepods, inorganic particles affect feeding efficiency, carbon turnover and egg production12 as well as mortality rates13. Deleterious effects such as reduced foraging, growth and changes in physiological condition have also been observed in fish14.

The Antarctic krill is a key species in the Southern Ocean trophic web15 and to the biological CO2 pump in the continental shelf of the Western Antarctic Peninsula (WAP) through the production of faecal pellets and the export of particulate carbon to deeper waters16. A strong decline in krill since the mid-1970 s has been associated with changes in sea ice17.

Potter Cove is a tributary fjord of Maxwell Bay in the southern coast of King George Island, South Shetland Islands, and is 4.7 km long and 1.6 km wide. A high krill abundance is characteristic of the oceanic waters off the South Shetland Islands and of spawning areas such as the Scotia Sea (average density approximately 25–50 and 50–100 ind m−2, respectively18). However, in nearshore waters, such as off Livingston Island, krill biomass densities have been shown to be higher, more stable and less variable than in the Scotia Sea19. To date, specific studies on krill abundance have not been conducted in bays such as Potter Cove and others along the WAP. However, the presence of krill is suggested by the stomach contents of the fish Notothenia coriiceps, the dominant benthic fish in Potter Cove20, which feeds primarily on krill21, and by the presence of whales feeding on krill inside the cove, as described for other coastal bays in the WAP22. Moreover, compared with the shelf and the slope, the coastal WAP showed a higher krill abundance between 1993 and 201323.

In the majority of the stranding events documented at Potter Cove since 2002, krill was the primary species found. Therefore, our aim was to understand the effect of the concentration and size of suspended particles on krill feeding, food absorption efficiency and survival. Here, we provide evidence showing that the quantity and quality of suspended inorganic particles are the cause of the mass krill strandings observed, providing the first insight into a phenomenon that may be crucial to the polar coastal marine food web in a warming world.

Results

Environmental conditions during krill stranding events

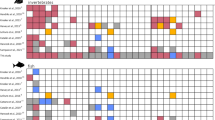

In the austral summer of 2003, four krill stranding events were detected on Potter Cove’s southern shore, but only 3 were quantified (the fourth event was documented after most of the krill had drifted out to sea or had been ingested by birds). The average density of dead krill on the beach in these events was 1,457 ± 740 ind m−2 of beach surface, of which 20% were adult krill, 2% were juveniles and 78% were larval krill; the total number of dead krill on the beach ranged between 130,000 and 413,000 individuals. The largest stranding event was observed in March 2007 (1,042 ± 277 ind m−2, 93% juveniles, 7% adults) along a 400 m coastline (Fig. 2) with a median total of approximately 423 000 individuals (range: 307,000 to 521,000). The environmental conditions during each of the recorded events are summarized in Table 1. Prior to the stranding events, the total amount of suspended particulate matter was similar for all documented events (p = 0.976) and was positively correlated with both the number of positive degree-days (PDDs) (t(23) = 2.604, p < 0.050) and the maximum tide amplitude (t(23) = 2.623, p < 0.050). Generalized linear models (GLMs) indicated that the probability of mass (≥100 ind m−2, category 2, Table 1) strandings increased directly with air temperature and maximum tidal amplitude. When a 24 h time lag was taken into account, total suspended particulate matter (TSPM) and wind speed showed a unimodal response such that high values (of both variables) were positively correlated with the probability of mass strandings. Not only was the maximum wind speed (>25 knots on average) important, but the dominant wind direction 24 h prior to the observed krill stranding events was also important (p < 0.050). Wind direction associated with category 2 events typically originated from the N and NW quadrants. Furthermore, when air temperature was >0 °C, a positive correlation with the strandings was evident.

Impact of the quantity of sediment on krill feeding activity

Krill showed a linear increase in feeding rate in response to increasing concentrations of natural phytoplankton cultures (with no added suspended particulate matter). The maximum feeding rate (14% body C d−1) was obtained at phytoplankton concentrations of 400 μg C L−1. In Potter Cove, the most frequent phytoplankton concentration ranged between 30 and 60 μg C L−1. Krill feeding on phytoplankton within this concentration range (which corresponds to our control treatment) showed an average daily carbon ration of 1.19 ± 0.10% body C d−1. In the feeding experiments with different quantities of added bottom sediment from Potter Cove (10, 40, 60, 80 and 100 mg TSPM L−1), even the lowest sediment concentration significantly decreased (p < 0.050) the daily carbon ration of adult krill to 0.42 ± 0.03% body C d−1 (Fig. 3a). There were no significant differences in the daily carbon ration among the different concentrations of added sediment (p < 0.050). In juveniles, the daily carbon ration was similar to the control for added sediment concentrations up to 40 mg TSPM L−1 and only decreased significantly at concentrations greater than 60 mg TSPM L−1 (p < 0.050, Fig. 3b). Shortly after the sediment was added (particle size <50 μm; see methods) to the phytoplankton, the digestive tract of the krill became a brown colour, indicating that the sediment had been ingested by the krill; this effect was similar to in situ observations of krill feeding in sediment-laden waters of Potter Cove (see supplementary material). When the feeding experiments were performed with in situ ‘brown water’ from Potter Cove (0.9 μg Chl-a L−1 and 17 mg TSPM L−1), the daily carbon ration dropped significantly, by more than 80% (p < 0.001) compared with experiments using clear water (Fig. 3c), suggesting that the quality and the size range of TSPM had an impact on krill feeding.

Absorption efficiency of krill in the presence of sediments

When juvenile krill fed only on natural phytoplankton cultures, in the absence of sediments, the absorption efficiency reached 88.29 ± 3.72%, whereas when fine (<50 μm) bottom-sediment was added (20 and 40 mg TSPM L−1), the absorption efficiency decreased to 21.44 ± 15.27 and 15.75 ± 3.62%, respectively (Fig. 4a). Once the sediment was added to the phytoplankton, faecal pellet production increased with increasing quantities of suspended particulate material (Fig. 4b). The rates of biodeposition (mg faecal pellets ind−1) and mass-specific biodeposition (mg faecal pellets g ind−1) were higher at higher particle concentrations (p < 0.001). Again, it was observed that the entire digestive system of krill exposed to increased quantities of particles was coloured brown. Moreover, at concentrations of 40 mg L−1 TSPM in both sets of experiments, 80% of animals stopped swimming and remained at the bottom of the tanks. Their feeding baskets and guts were brown-coloured (Fig. 4c) with sediments particles adhering to the surface, very probably affecting their capacity for feeding.

(a) Absorption efficiencies and (b) biodeposition rates (in mg fecal pellets ind−1 and mass-specific biodeposition rates (in mg fecal pellets g ind−1) of krill fed with natural seston to which two different amounts of sediments were added. TSPM: Total suspended particulate matter. (c) Pictures of krill after the feeding experiments with high concentrations of suspended particulate material. Red arrows point to the particles in the feeding apparatus of the animals. Credit photos: V. Fuentes.

Analyses of krill from 2008 and 2009 stranding events

The entire digestive system of the stranded krill collected during 2008 and 2009 was filled with brown particles, and the digestive gland was a pale yellow-grey colour. Body and stomach wet weights showed no significant differences between the different mortality events (p = 0.083 and p = 0.490 for body and stomach, respectively, Table 2) and were similar to the body and stomach weights of living krill collected from net tows in clear waters of Potter Cove (Fig. 5a). The digestive glands in living krill had a greenish colour, suggesting ingestion of phytoplankton. Centric pelagic and some benthic, pennate diatoms were the major items in the stomach contents of these animals (Fig. 5b). Diatoms were also present in the digestive tract of dead krill; total diatom volume did not vary among mortality events (p < 0.050) (Table 2) but was significantly lower than in the stomachs of living krill (Mann-Whitney U = 16; p < 0.001). However, highly significant differences were found in the total amount of lithogenic particles between dead and living krill (p < 0.001) in both years. Dead krill had more than two times the volume of lithogenic particles in their digestive tract than living krill. Large irregular lithogenic particles (>1.1 105μm3 volume, equivalent to >75 μm diameter) represented a large fraction of the contents of the digestive tract in dead krill for all three mortality events in the 2008 and 2009 seasons, and no significant difference in the volume of lithogenic particles in dead krill was found between these events (p = 0.840). Very large particles, in the 1.4 106–5.2 106μm3 range (175–275 μm length), were only found in the stomachs of krill from the mass mortality events (Fig. 5c).

(a) Proportion of inorganic particles and diatoms in the gut contents of stranded krill from 2008 to 2009. (b) Size classes of the lithogenic particles found in living krill and during the analysed strandings. (c) Relative contributions of different diatom species. Note the dominance of the planktonic genera Coscinodiscus sp. and Thalassiosira sp. (d) The relatively sharp angles of the particles as seen under the SEM, indicative of local and relatively recent origin. Credit photos: G. Aguirre.

Discussion

Mass mortality events of marine organisms are receiving increasing attention. A comprehensive revision has been recently published24. The presence of particulate matter has been invoked as the cause for salp and copepod deaths in coastal environments1,13.

In light of our findings, we have strong evidence that the quantity and quality of lithogenic material in the water column can be a significant threat for krill in the shallow coastal regions of the Antarctic Peninsula. We postulate that the ingestion of large lithogenic particles (>1.1 105μm3), which are most likely of glacial origin, is the primary cause of the krill mass mortalities studied. This study is the first documentation of the impact of large quantities and large sizes of lithogenic particles on krill.

Krill is a very effective filter feeder25 adapted to food sources of varying size and density15. They have often been observed feeding near sea floor sediments in coastal areas26 and have been recorded feeding in meltwater plumes (see supplementary material). Stomach content analyses suggest that krill are adapted to sporadically cope with a certain level of sediment, as evidenced by the gut content analysis of living krill, both here and in previous studies (e.g., 26). The results from our feeding experiments, in which fine bottom sediments from Potter Cove were added to natural plankton, demonstrate that this type of material, even in low concentrations (10 mg L−1 TSPM), has a strong impact on the performance of adult krill. Juveniles showed a similar response at particle concentrations >60 mg L−1. The difference between these age groups may be due to the mean mesh interval of their filtration apparatus. For juvenile krill, this ranges between 19 and 36 μm27, which is smaller than the maximum size of the bottom sediment particles used in these experiments. It is probable that most particles did not enter their digestive tract. However, at high concentrations, their filtering basket gets clogged (see Fig. 4c). By contrast, the mean mesh interval of adult krill ranges from 68 to 83 μm, such that 50 μm particles were not filtered out and immediately entered their digestive tract, severely affecting their body carbon ration and hence their overall performance, as evidenced by the cessation of movement and their position at the bottom of the tank. However, the feeding experiments with “brown water” from Potter Cove that originated from glacial melting showed that even a low particle concentration (17 mg L−1 TSPM) had a serious negative impact on the daily carbon ration and overall condition of juvenile krill. This impact was similar to the experiment in which 100 mg L−1 TSPM of fine bottom sediment was added. The mean grain size of the sediment transported via glacier meltwater into the cove ranges from 6 to 781 μm6. The size of the bottom sediments used for the experiment was <50 μm. Therefore, according to our experimental results, in addition to the quantity of TSPM, the quality of TSPM is also probably having an impact on the daily carbon ration and performance of krill. Moreover, when particles were added to the food, an immediate increase in faecal pellet production was noted, which diminished the gut residence time.

Due to the morphology and the function of specific organs, the krill’s ability to process lithogenic particles is limited. Before large cells can be ingested, the mandibular pars molaris of krill split diatom chains and cut or fracture hard particles27. Ingested solid food particles are further macerated and crushed by the gastric mill, which is located inside the stomach, and mixed with digestive enzymes28,29. The processed material is then pressed through a fine filter system that allows fine food particles (<0.2 μm) to enter the midgut, where they are further digested. It is probable that the gastric mill of krill is not able to crush and grind lithogenic particles. Although coarse food residues, together with small lithogenic particles, can be transported directly to the hindgut25, large lithogenic particles may not enter the hindgut due to their size. This may represent an interruption of the passage of ingested particles, suggesting that the ingestion of large lithogenic particles (>1.1 105μm3) could also mechanically disrupt the krill intestine. Lithogenic particles were found in the stomach contents of both dead and live krill but represented only a small proportion of the stomach contents of living krill. In addition, no particles >1.3 106μm3 (175 μm length) were found in live krill. The large size and shape of the lithogenic particles found in the stranded krill guts suggest that this is relatively recent material of glacial origin, with sharp angles compared with particles from the bottom. The diatom species composition in dead krill guts showed a dominance of pelagic diatoms (Coscinodiscus spp. and Thalassiosira spp., Fig. 5b), indicating that the lithogenic particles in the water column are of glacial origin rather than resuspended from the bottom of the Cove.

Krill can normally avoid unfavourable environments. At Potter Cove, strong and long-lasting N and NW winds are able to build up significant waves that strike the beach at high frequency, hindering the rapid deposition of glacial particles and increasing resuspension in the wave zone. These winds force the meltwater plumes to the southern shore, further increasing the local particulate material concentration in the water5. Under such conditions, krill may become trapped in the surf zone close to the beach, ingesting whatever material is present there. Therefore, according to our findings, the consequences for krill are twofold: first, krill cannot cope with a large concentration of lithogenic particles and their filter system becomes clogged, and second, the large quantity of large lithogenic particles interrupts the passage of ingested particles, the accumulation of food in the stomach and hence nutrient absorption. The krill become weak and are easily transported by the waves onto the beach or die in the water.

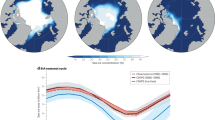

Earlier studies have documented the presence of particle-laden “brown water” in Potter Cove5. During the storms that occur throughout the active glacial melting periods, the concentration of particulate matter can be >100 mg L−1 10. Over the last six decades, 87% of 244 studied glacier fronts have retreated along the WAP30, increasing the discharge of glacial meltwater and particles into the coastal marine ecosystem2. Approximately 90% of King George Island’s surface is covered by glaciers that are undergoing the same process, increasing the runoff of meltwater into the bays and fjords of the island31,3,4. The size and angular shape of the particles recovered from stranded krill guts in this study (Fig. 5d) indicate a relatively short transport time of the particles and therefore a local origin, most likely directly from the Fourcade Glacier and its associated meltwater streams. These glacially derived particles exceed the average grain size of particles deposited on the seafloor in Potter Cove6, suggesting special discharge events. However, the quantity of material discharged by meltwater forms conspicuous sediment plumes that become part of the coastal waters and can be traced for many tens of kilometres32. High diffuse attenuation coefficients (Kd) in coastal polar areas have been correlated with the presence of suspended inorganic particles33. The extension of these highly turbid waters can be clearly seen in summer along the northern WAP, particularly near the coasts such as those around King George Island (Fig. 6). These plumes show the potential extent of the area over which krill survival could be threatened. Indeed, the area around Antarctica that is estimated to be affected by changes in the extension of tidewater glaciers alone and their impacts on the biota is 2.97 × 106 km2 9.

Moderate-resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) Aqua Ocean Color Data; 2014 Reprocessing. NASA OB.DAAC, Greenbelt, MD, USA. doi: 10.5067/AQUA/MODIS_OC.2014.0. (Accessed on 12/10/2015). MODIS satellite images of the northern WAP and King George Island. Land is shown in black and clouds in white, and Kd is grey scaled. (a) January 16, 2013, showing relatively high values of Kd along the coasts of King George Island and lower values along the WAP coast. (b) January 16, 2014, showing a detail of the King George Island area, with relatively high values of Kd. In this image, the WAP is covered by clouds and therefore not visible to the satellite and has therefore been omitted. Different dates are presented to highlight the persistence of the phenomenon. Note the difference in Kd scales between images.

An increase in meltwater runoff will additionally reduce surface water salinity and could trigger osmotic stress, as observed for phytoplankton34 and amphipods in coastal Arctic waters35. However, krill are osmoconformers, and salinities in the range of 25 to 45 psu have little effect on their metabolism36. Surface water warming could be an additional source of stress for krill. However, early experiments with temperatures varying from −1 to 10 °C have shown that krill are able to tolerate some exposure to high temperatures by lowering their metabolic rate37. The mortality observed in this study should therefore not be related to these stressors but to the amount and the size of glacially derived lithogenic particles. A similar impact was observed on copepods and amphipods in Arctic fjords38. Furthermore, krill strandings were correlated with strong N or NW winds in combination with maximum tidal amplitudes. These conditions would lead krill to ingest large quantities and large sizes of lithogenic particles, debilitating the krill. The particle shape further suggests that the lithogenic material is recently derived from the Fourcade Glacier and its associated meltwater streams.

The poor record of krill strandings and the relatively low number of stranded animals would indicate that these are rare events. However, the probability of detecting a stranding event depends on specific physical conditions that push the dead organisms onto the beaches. The number of strandings we observed probably reflects only a small fraction of all the sediment-related krill mortality events, as most coastal areas in Antarctica are not monitored. Most of these dead krill will eventually settle on the sea floor to become part of the benthic food web, thereby remaining undocumented. The importance of dead krill as a source of organic matter for benthic organisms has been previously documented39. In addition, the delay between a stranding and its observation is also crucial for the quantification of dead animals. Not only will tides and waves wash the dead organisms out back to the sea, but also animals such as birds will also profit from this easily available food source.

Environmental conditions around Antarctica are changing; in particular, positive air temperature, related to glacial melting, has increased and westerly winds, which are related to the krill stranding events in Potter Cove, have become more frequent in recent decades40. The Western Antarctic Peninsula (WAP) is one of the most rapidly warming areas on Earth41, and krill is the most abundant species in the coastal areas of this region23; predators such as fish, seabirds, penguins, seals and whales rely on this single resource. The presence of numerous krill-feeding whales in fjords, such as Potter Cove and others along the WAP, as well as the presence of the dominant benthic fish species Notothenia coriiceps, which feeds primarily on krill20, underscore the importance of krill for these regions. Of the total krill stock in the Southern Ocean, the majority live over deep oceanic water42, suggesting that the increasing discharge of glacial meltwater and particles into the coastal zones of the WAP might not affect the entire krill stock. However, summer (when glacier melting and sediment input are highest) is a critical time of the year for krill, particularly in terms of the energetic demand to fuel growth and reproduction43. In summer, cross-shelf gradients result in a higher abundance of krill inshore and over the continental shelf44,45. For example, some inshore regions, such as the Bransfield Strait, experience pulses of increased faecal flux associated with high populations of krill46. Thus, due to the central role of krill in these regions, an increasing loss of krill would have a large impact on the functional biodiversity of coastal systems. If krill in coastal areas are increasingly affected by sediments and mortality removes a proportion of them from the water column, birds and mammals relying on krill will have higher energetic costs associated with fulfilling their nutritional demands; this effect has been observed for species such as the Adélie penguin47, the abundance of which has changed in the area around Potter Cove. In addition, the strong decrease in krill biomass since the mid-1970s has been attributed to the decrease in winter sea ice cover33. Other investigations have demonstrated that krill appear to be sensitive to increasing seawater temperature48 and ocean acidification49. However, the krill’s performance window with regard to stressors related to anthropogenic warming is far from clear. The increasing threat to krill due to increasing glacier melt might be not be significant in the context of the current total stock, but in the long term, it is one additional threat among a number of stressors caused by climate change, which will increase and, in combination with other factors, will most likely impact the stock in the future.

Materials and Methods

Krill mortality events

Mortality events of krill were observed on several occasions on the southern shore of Potter Cove (Table 1). The first event was detected in 2003, and from 2003 to 2012, monitoring of the coastline in the vicinity of Carlini Station was performed when the cove was free of ice. It should be noted that more events may have gone undetected during the years of the study. Quantification of the number of dead animals was not always possible; therefore, a presence-absence matrix was constructed using qualitative categories for abundance as follows: 0 (absence of krill), 1 (abundances from 10 to 102 krill m−2) and 2 (>102 krill m−2). For the strandings, all organisms along a 10 m × 1 m transect (2003) and within a 1 m × 1 m square (2007) were counted and classified as adults, juveniles or larvae. In some of the events, other planktonic organisms were identified but not quantified; those data are not presented here. An absence of krill was recorded for dates during the period in which stranding events were studied when the water column was sampled and no stranded krill were found.

Environmental data

Fifteen krill stranding events were recorded. Environmental information for seventeen samplings during the study period in which no stranding event occurred is included in the analyses. Meteorological data were supplied by the Servicio Meteorológico Nacional (SMN) of the Argentinean Air Force at Carlini Station, and tidal heights were provided by the Servicio de Hidrografía Naval (SHN) of Argentina. The mean and maximum wind speed for the 24 h preceding the sampling date and the predominant direction of the strongest wind were determined. The average air temperature was calculated for the week preceding the sampling events. In addition, the positive degree-days (PDDs) was estimated by adding the positive daily average temperatures for the previous month to the sampling event.

The mean values of the oceanographic parameters were used for the integrated water column. Because meteorological and wind conditions during the stranding events usually prevented oceanographic sampling, the closest date for which information was available was used. When the closest date was more than 10 days before the stranding event, no data were considered available. The oceanographic data are part of a long-term monitoring program that started in 1991, in which the water column in Potter Cove is sampled weekly in the summer and biweekly in the winter, whenever the meteorological conditions allow sampling. A SeaBird SBE Conductivity-Temperature-Depth profiler (CTD; SeaBird Electronics) was used to record seawater temperature and conductivity (transformed to salinity). However, water temperature and salinity were not included in the analyses because insufficient data were available for the studied dates. Water samples were collected at five depths (i.e., 0, 5, 10, 20, and 30 m) with 4.7 L Niskin bottles. For Chl-a analysis, seawater (0.25–2 L) was filtered through 25 mm Whatman GF/F filters under gentle vacuum and dim light. Photosynthetic pigments were extracted in 90% acetone for 24 h at 4 °C in the dark. Extract absorbance was read using a Shimadzu RF-1501 spectrophotometer, and concentrations were calculated and corrected for phaeopigment content following the method of Strickland and Parsons50. The total suspended particulate material (TSPM) concentration was measured gravimetrically after filtering 0.25–2 L of seawater through combusted pre-weighed 25 mm Whatman GF/F filters. After filtration, the filters were rinsed twice with distilled water to remove salts and then dried for 24 h at 60 °C and weighed again. All environmental data are available at http://doi.pangaea.de/10.1594/PANGAEA. The relation between the proposed explanatory variables and the number of stranding events was analysed by means of Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) using a Poisson error distribution family and a log-link to ensure only positive model predictions. To find the optimal model, we followed a backward selection criterion, where the process ended when all the variables retained during the selection were significant. The analysis of the relation between TSPM and the other environmental variables followed the same approach, using a Gaussian error distribution family (generalized linear model). To visualize the effects of environmental variables over the modelled probability of mass strandings (from the GLMs), the visreg function (visreg package) was used51. Partial effects reflect the effect of a particular environmental factor on the response variable (mass stranding category) holding all other variables constant (in this case, the median value of the numerical variables and the most common category were used as factors).

MODIS-Aqua spatially extracted Level-2 files were acquired for the study area from the NASA ocean color web page (http://oceancolor.gsfc.nasa.gov). Two images (January 16, 2013 and January, 16 2014) were chosen because of their relatively low cloud cover over the area of interest.

The standard Kd, the diffuse attenuation coefficient, product derived from Kd2 algorithm52 was obtained. This Kd product was updated using in situ data from NOMAD version 2. The algorithm form describes the polynomial best fit relating the log-transformed geophysical variable to a log-transformed ratio of remote-sensing reflectance (Rrs) as Rrs(490 nm)/Rrs(555 nm). Kd was mapped to a WGS 84 reference system (datum WGS84, ellipsoid WGS84 at 1100 m of spatial resolution at nadir and co-registered with respect to a reference landmask), and used as a proxy for the presence of inorganic particles in the water column33. Land and cloudy pixels were flagged to zero.

Feeding and absorption efficiency experiments

Juveniles and adults of E. superba were collected from the outer part of Potter Cove using a 200 μm mesh Nansen net with a 2 L cod end, towed vertically (100 m below the surface) and obliquely with a winch installed on a Zodiac rubber raft. The cod end was immediately transferred to a 50 L plastic bucket filled with filtered seawater and then immediately transferred to a cold room (0 °C) where the animals were placed in a 100 L container.

A Sartorius MC1 balance (precision = 10−4g) was used to determine wet weight. To estimate dry weight, animals were placed on aluminium foil and dried at 60 °C for 3 days and then weighed again. The organic content was determined by ashing the tissues at 500 °C for 4.5 h and calculating the difference between wet and dry weights. Faecal pellets were processed in the same manner as krill.

Feeding experiments

A natural phytoplankton culture was used as food for the experimental incubations. Phytoplankton were collected using 5 L Niskin bottles. The content of the bottles was transferred to 30 L aquaria (located in the cold room at 0 °C) previously filled with filtered sea water. A series of 5 phytoplankton cultures were established, and the Chl-a concentration was measured every second day to track phytoplankton growth. A series of three experiments were performed to estimate feeding rates. The first experiment was performed on increasing phytoplankton concentrations from the cultures describe above. The phytoplankton were diluted in filtered seawater to attain the various experimental concentrations, without any added sediment. This dilution process allowed determination of the daily ration (see below) for each phytoplankton concentration. The second experiment used a fixed phytoplankton concentration (based on the most typical field Chl-a concentrations for the area2), to which different concentrations of particulate matter (0.1, 10, 40, 80 and 100 mg TSPM L−1) were added, reflecting the range of in situ concentrations recorded in Potter Cove1,10. The added particles were obtained from natural sediments taken from the seafloor of the inner cove with a Van Veen grab sampler at a 20 m depth, near a creek mouth. Sediments were dried at 70 °C and sieved through a 50 μm mesh sediment sieve. This size fraction was chosen because it could be easily resuspended in seawater. The organic fraction of the sediments was determined by ashing the filtered material for 4 h at 400 °C and then re-weighing the sample. The average proportion of organic matter was 2.36 ± 0.07%. Experiments were run on adult (45.22 ± 0.44 mm length, 515.46 ± 159.52 mg DW, 257.73 ± 79.76 C content) and juvenile (26.57 ± 0.71 mm length, 36.81 ± 2.22 DW, 18.40 ± 1.11 C content) krill. The total length of krill (mm) was measured from the front of the eye to the tip of the telson. Four juveniles were placed in each of 3 replicate 2.4 L bottles. The bottles were installed in a plankton wheel to maintain the food and sediments in suspension and ensure an equal concentration in all the bottles. For adult krill, 10 organisms were placed in 60 L containers equipped with a gentle mixing system to ensure that the food and the sediments always remained suspended. The experiment was run for 24 h. Once completed, animals were lyophilized for 24 h, and individuals were weighed and ground to powder in liquid nitrogen. For analysis of C, 0.2–0.5 mg aliquots of each krill homogenate were analysed15,50.

A similar experiment was run with juveniles, comparing two different natural waters from Potter Cove, designated as brown and clear waters. Brown water contained 17 mg L−1 TSPM and 0.9 μg Chl-a L−1, while clear water contained 10 mg L−1 TSPM and 1.3 μg Chl-a L−1. Four juveniles were placed in each of 3 replicate 2.4 L bottles. The experiment was run for 24 h.

All experimental conditions were maintained at a temperature of 0 ± 0.48 ° C and salinity 34 ± 0.3.

Chl-a was analysed on 3 replicate 250 mL samples from each container at the beginning and after 24 h incubation29,53. Feeding was estimated as clearance rate (CR, ml mg−1 body C h−1). No significant changes in Chl-a concentration were detected in the controls (no krill), so that CR was calculated as54:

where Cc and Ck are the initial and final Chl-a concentrations, respectively, V is the volume of the container (ml), mk is the body mass (mg C) of the krill, and t is the duration of the experiment (h). Ingestion rates (IR) were calculated as the product of CR and the initial carbon concentration (mg ml−1) as IR = CR.Ci and then expressed as the daily carbon ration (% body C d−1) under the assumption that krill feeding rates reflect the daily average rate.

The depletion of autotrophic biomass ranged between 1 and 20% in all experiments.

Single factor, one way ANOVA was used to evaluate the effects of TSPM on the daily carbon ration for both, adult and juvenile individuals of E. superba. When significant (p < 0.050) differences were detected post-hoc Tukey HSD tests were run. The daily carbon ration was log (+0.5) transformed to pass homogeneity and normality assumptions55. Analyses were run under the free statistical software R, version 2.15.156.

Absorption efficiency experiments

The effect of the concentration of particles on the absorption of organic matter and the production of faeces was investigated using natural seston as a food and two different concentrations of fine sediments. The organic fraction in the added sediments was 1.87 ± 0.1%. Three experimental conditions were used: 1) no added sediment (TSPM = 2.39 ± 0.5 mg L−1), 2) natural seston + 20 mg L−1 sediment (TSPM = 22.3 ± 1.6 mg L−1), 3) natural seston + 40 mg L−1 sediment (TSPM = 42.8 ± 2.3 mg L−1). Prior to the experiments, animals were starved during 48 h in GF/F filtered seawater to empty their stomachs. Six cylindrical 8 L aquaria with individual recirculation pumps were settled in a running 90 L sea water flow bath to keep water at in situ temperatures (0 ± 1 °C). A 200 μm mesh was fitted 10 cm above the bottom of each aquarium to allow water to flow and avoid the disruption of the faecal pellets in the circulating system. One control (no krill) and five replicates with 12 animals each (size range: 35–46 mm total length) were used for each experiment. Incubations lasted for 24 h, and no dead animals were registered in any of the experiments. There was no significant difference between initial and final TSPM concentrations in the control aquaria among different experimental trials, and therefore a correction for sedimentation of particles was not needed.

The absorption efficiency was estimated using the Conover ratio57, which assumes that only the organic component of the food is significantly affected by the digestive process. Thus, the absorption efficiency was obtained as the difference of the ratio of mass loss after food combustion, and the corresponding percentage of mass loss after combustion of faeces: Absorption efficiency  where F is the organic fraction in the food and E is the organic fraction in the faeces. The absorption efficiency was then reported as percentage. The time elapsed between food delivery and faeces production was recorded. The biodeposition rate was calculated as the dry weight of faeces produced per individual per day. The weight-specific biodeposition rate was referred to animal body mass per day. The faeces were collected every 30 minutes during the first 6 h of incubation and then every hour; the faeces were pooled for absorption efficiency calculations.

where F is the organic fraction in the food and E is the organic fraction in the faeces. The absorption efficiency was then reported as percentage. The time elapsed between food delivery and faeces production was recorded. The biodeposition rate was calculated as the dry weight of faeces produced per individual per day. The weight-specific biodeposition rate was referred to animal body mass per day. The faeces were collected every 30 minutes during the first 6 h of incubation and then every hour; the faeces were pooled for absorption efficiency calculations.

Differences among treatments were analysed using one-way ANOVA, since all data met the assumptions of ANOVA analysis. Normality of residuals was tested by mean of Shapiro-Wilks test58, while homoscedasticity was confirmed by Levene’s test59. When significant differences were encountered, the Tukey–Kramer method60 was used as a post-hoc test to identify significant differences among the means. Statistical analyses were run with the softwares InfoStat v.61 and PAST v. 3.0462.

Krill stomach content analyses

Freshly dead or dying krill (referred in the text as ‘dead krill’) were collected along the coastline and from shallow coastal waters during the mortality events of 2008 and 2009. Samples were blotted dry and stored at −80 °C for stomach content analyses at the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (Bremerhaven, Germany). During those years, zooplankton and water samples were collected from a rubber boat at the inner part of the cove. Healthy krill (referred in the text as ‘living krill’) was caught only once during this period. The stomach content was compared with that from dead krill. Ten adult krill individuals sampled during each of the stranding events and of the catchment were studied (n = 40). Wet body weight was registered before dissection. Then, the exoskeleton was removed and the stomach was taken out and weighed. Stomach contents were analysed29 and an Utermöhl chamber was used to count and identify the particles. Abundant size classes (>100 particles) were counted in two perpendicular transects across the chamber, while for the less abundant size classes the whole chamber was counted at 250×. The dimensions of the different items in the stomachs were measured and their biovolume calculated63,64. The lithogenic particles found in the stomach contents were enumerated and grouped into size intervals according to their length as follows: <3.8, 3.8–7.5, 7.6–18.8, 18.9–37.5, 37.6–56.3, 56.4–75.0 and >75.0 μm. The length of each particle was measured and its volume estimated assuming a rectangular parallelepiped form with width and height half their length.

The wet weights and the composition of the stomach content did not follow a normal distribution, and therefore medians and percentages were calculated to compare the data among the three events in which stomach content was studied by means of Kruskal-Wallis test. When no differences among strandings were found, data were grouped and compared with the results from living krill by means of Mann-Whitney’s test.

For the scanning electron microscope (SEM) analyses, the stomach and the hindgut were removed from the frozen krill, and their contents released separately in Eppendorf tubes. The samples were prepared65, with certain modifications. Briefly, each of the stomach contents was washed 5 times with deionized water to remove salt. Then, the sample was cooked in NaOH 1N at 60 °C during 2 h to remove the rest of stomach and gut tissues, and washed again 5 times with deionized water. The sample was then filtered on 0.1 μm cellulose nitrate membrane filter and air-dried. Filters were mounted on SEM stubs and sputtered with gold-palladium (ca. 20 nm thickness). Images were taken with a FEI Quanta 200 FEG microscope.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Fuentes, V. et al. Glacial melting: an overlooked threat to Antarctic krill. Sci. Rep. 6, 27234; doi: 10.1038/srep27234 (2016).

References

Pakhomov, E. A., Fuentes, V., Schloss, I. R., Atencio, A. & Esnal, G. B. Beaching of the tunicate Salpa thompsoni at high levels of suspended particulate matter in the Southern Ocean. Polar Biol. 26, 427–431 (2003).

Schloss, I. R. et al. Response of phytoplankton dynamics to 19-year (1991–2009) climate trends in Potter Cove (Antarctica). J Mar. Syst. 92, 53–66 (2012).

Rückamp, M., Braun, M., Suckro, S. & Blindow, N. Observed glacial changes on the King George Island ice cap, Antarctica, in the last decade. Global Planet. Change. 79, 99–109 (2011).

Simões, J. C., Dani, N., Bremer, U. F., Aquino, F. E. & Neto, J. A. Small cirque glaciers retreat on Keller Peninsula, Admiralty Bay, King George Island, Antarctica. Pesqui. Antart. Bras. 4, 49–56 (2004).

Klöser, H. et al. Hydrography of Potter Cove, a Small Fjord-like Inlet on King George Island (South Shetlands). Estuar. Coast Shelf S. 38, 523–537 (1994).

Wölfl, A. C. et al. Distribution and characteristics of marine habitats in a subpolar bay based on hydroacoustics and bed shear stress estimates—Potter Cove, King George Island, Antarctica. Geo-Marine Letters. 34, 435–446 (2014).

Monien, P. et al. A geochemical record of late Holocene palaeoenvironmental changes at King George Island (maritime Antarctica). Antarct. Sci. 23, 255–267 (2011).

Thrush, S. F. et al. (2004) Muddy waters: elevating sediment input to coastal and estuarine habitats. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2, 299–306 (2004).

Gutt, J. et al. The Southern Ocean ecosystem under multiple climate change stresses - an integrated circumpolar assessment. Glob. Change Biol. 21: 1434–453 (2015).

Philipps, E. E. R., Husmann, G. & Abele, D. The impact of sediment deposition and iceberg scour on the Antarctic soft shell clam Laternula elliptica at King George Island, Antarctica. Antarct. Sci. 23, 127–138 (2011).

Torre, L. et al. Respiratory responses of three Antarctic ascidians and a sea pen to increased sediment concentrations. Polar Biol. 35, 1743–1748 (2012).

Arendt, K. E. et al. Effects of suspended sediments on copepods feeding in a glacial influenced sub-Arctic fjord. J. Plankton Res. 33, 1526–1537 (2011).

Carrasco, N. K., Perissinotto, R. & Jones, S. Turbidity effects on feeding and mortality of the copepod Acartiella natalensis (Connell and Grindley, 1974) in the St Lucia Estuary, South Africa. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 446, 45–51 (2013).

Wenger, A. S., Johansen, J. L. & Jones, G. P. Increasing suspended sediment reduces foraging, growth and condition of a planktivorous damselfish. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 428, 43–48 (2012).

Meyer, B. The overwintering of Antarctic krill, Euphausia superba, from an ecophysiological perspective. Polar Biol. 35, 15–37 (2012).

Gleiber, M. R., Steinberg, D. K. & Ducklow, H. W. Time series of vertical flux of zooplankton fecal pellets on the continental shelf of the western Antarctic Peninsula. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 471, 23–36. 10.3354/meps10021 (2012).

Atkinson, A., Siegel, V., Pakhomov, E. & Rothery, P. Longterm decline in krill stock and increase in salps within the Southern Ocean. Nature. 432, 100–103 (2004).

Flores, H. et al. Impact of climate change on Antarctic krill. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 458, 1–19, 10.3354/meps0983 (2012).

Warren, J. D. & Demer, D. A. Abundance and distribution of Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba) nearshore of Cape Shirreff, Livingston Island, Antarctica, during six austral summers between 2000 and 2007. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 67, 1159–1170 (2010).

Barrera-Oro, E. R. & Casaux, R. J. Feeding selectivity in Nothotenia neglecta, Nybelin, from Potter Cove, South Shetland Islands, Antarctica. Antarct. Sci. 2, 207–2013 (1990).

Fanta, E., Sant´Anna Rios, F., Donatti, L. & Cardoso,, W. E. Spatial and temporal variation in krill consumption by the Antarctic fish Notothenia coriiceps, in Admiralty Bay, King George Island. Antarct. Sci. 15, 458–462 (2003).

Nowacek, D. P. et al. Super-aggregations of krill and humpback whales in Wilhelmina Bay, Antarctic Peninsula. PLoS One. 10.1371/journal.pone.0019173 (2011).

Steinberg, D. K. et al. Long-term (1993–2013) changes in macrozooplankton off the Western Antarctic Peninsula. Deep-Sea Res. I 101, 54–70 (2015).

Fey, S. B. et al. Recent shifts in the occurrence, cause, and magnitude of animal mass mortality events. Proc. Nac. Acad. Sci. 10.1073/pnas.1414894112 (2015).

Ullrich, B., Storch, V. & Marschall, H. P. Microscopic anatomy, functional morphology, and ultrastructure of the stomach of Euphausia superba Dana (Crustacea, Euphausiacea). Polar Biol. 11, 203–211 (1991).

Schmidt, K. et al. Seabed foraging by Antarctic krill: Implications for stock assessment, bentho-pelagic coupling, and the vertical transfer of iron. Limnol. Oceanogr. 56, 1411–1428 (2011).

McClatchie, S. & Boyd, C. M. Morphological study of sieve efficiencies and mandibular surfaces in the Antarctic krill, Euphausia superba. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 40, 955–967 (1983).

Suh, H. L. The gastric mill of euphausiid crustaceans: a comparison of eleven species. Hydrobiologia. 321, 235–244 (1996).

Suh, H. L. & Toda, T. Morphology of the gastric mill of the genus Euphausia (Crustacea, Euphausiacea). Bull. Plankton Soc. Japan. 39, 17–24 (1992).

Cook, A. J., Fox, A. J., Vaughan, D. G. & Ferrigno, J. G. Retreating Glacier Fronts on the Antarctic Peninsula over the past Half-Century. Science. 308, 541–544 (2005).

Park, B. K., Chang, S. K., Yoon, H. I. & Chung, H. Recent retreat of ice cliffs, King George Island, South Shetland Islands, Antarctic Peninsula. Ann. Glaciol. 27, 633–635 (1998).

Vogt, S. & Braun, M. Influence of glaciers and snow cover on terrestrial and marine ecosystems as revealed by remotely-sensed data. Pesquisa Ant. Brasil. 4, 105–118 (2004).

Lund-Hansen, L. C., Andersen, T. J., Nielsen, M. H. & Pejrup, M. Suspended matter, Chl-a, CDOM, grain sizes, and optical properties in the Arctic fjord-type estuary, Kangerlussuaq, West Greenland during summer. Estuar. Coasts. 33, 1442–1451 (2010).

Hernando, M. et al. Effects of salinity changes on coastal Antarctic phytoplankton physiology and assemblage composition J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 466, 110–119 (2015).

Eiane, K. & Daase, M. Observations of mass mortality of Themisto libellula (Amphipoda, Hyperidae). Polar Biol. 25, 396–398. 10.1007/s00300-002-0361-3 (2002).

Aarset, A. V. & Torres, J. J. Cold resistance and metabolic responses to salinity variations in the amphipod Eusirus antarcticus and the krill Euphausia superba . Polar Biol. 9 (8), 491–497 (1989).

Tremblay, N. & Abele, D. Response of three krill species to hypoxia and warming: an experimental approach to oxygen minimum zones expansion in coastal ecosystems. Mar. Biol. 10.1111/maec.12258. 1–21 (2015).

Węsławski, J. M. & Legeżyńska, J. Glaciers caused zooplankton mortality? J. Plankton Res. 20, 1233–1240 (1998).

Sokolova, M. N. Euphausiid “dead body rain” as a source of food for abyssal benthos. Deep-Sea Res. I 41(4), 41–746 (1994).

Zhang, J. Modeling the impact of wind intensification on Antarctic sea ice volume, J. Clim. 27, 202–214, 10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00139.1 (2013).

Ducklow, H. W. et al. Marine pelagic ecosystems: the West Antarctic Peninsula. Philos. T. Royal Soc. B. 362, 67–94 (2007).

Atkinson, A. et al. Oceanic circumpolar habitats of Antarctic krill. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 362, 1–23 (2008).

Hofmann, E. E. & Lascara, C. M. Modeling the growth dynamics of Antarctic krill Euphausia superba. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 194, 219–231 (2000).

Ross, R. M. et al. Palmer LTER: patterns of distribution of five dominant zooplankton species in the epi-pelagic zone west of the Antarctic Peninsula, 1993−2004. Deep-Sea Res. II 55, 2086–2105 (2008).

Bernard, K. S., Steinberg, D. K. & Schofield, O. M. E. Summertime grazing impact of the dominant macrozooplankton off the western Antarctic Peninsula. Deep-Sea Res. I 62, 111–122 (2012).

Schnack-Schiel, S. B. & Isla, E. The role of zooplankton in the pelagic-benthic coupling of the Southern Ocean. Sci. Mar. 69, 39–55 (2005).

Juáres, M. A. et al. Adélie penguin population changes at Stranger Point: 19 years of monitoring. Antar. Sci. 27, 455–461 (2015).

Atkinson, A. et al. Natural growth rates in Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba): II. Predictive models based on food, temperature, body length, sex, and maturity stage. Limnol. Oceanogr. 51, 973–987 (2006).

Kawaguchi, S. et al. Risk maps for Antarctic krill under projected Southern Ocean acidification. Nat. Clim. Change. 3, 843–847 (2013).

Strickland, J. D. H. & Parsons, D. R. A practical handbook of seawater analysis. Bull. Fish. Res. Board Can. 167, 1–310 (1972).

Breheny, P. & Burchett, W. Visreg: Visualization of Regression Models. R package version 2.2-0. Available from http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=visreg [Accessed on February 25 2016] (2015).

Mueller, J. L. SeaWiFS algorithm for the diffuse attenuation coefficient, K(490), using water-leaving radiances at 490 and 555 nm in SeaWiFS postlaunch calibration and validation analyses: Part 3, NASA Tech. Memo. 2000-206892, vol. 11 (eds Hooker, S. B., Firestone, E. R. ) 24–27 (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland, 2000).

Meyer, B., Atkinson, A., Blume, B. & Bathmann, U. V. Feeding and energy budgets of larval Antarctic krill Euphausia superba in summer. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 267, 167–177 (2003).

Båmstedt, U. et al. In ICES Zooplankton Methodology Manual (eds Harris, R., Wiebe, P., Lenz, J., Skjoldal, H. R., Huntley, M. ) 297–399 (Academic Press, 2000).

Quinn, G. P. & Keough, M. J. Potential effect of enclosure size on field experiments with herbivorous intertidal gastropods. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 98, 199–201 (1993).

R Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL http://www.R-project.org/ (2014).

Conover, R. J. Assimilation of organic matter by zooplankton. Limnol. Oceanogr. 11, 338–354 (1966).

Mahibbur, R. M. & Govindarajulu, Z. A. Modification of the test of Shapiro and Wilks for normality. J. Appl. Statist. 24, 219–235 (1997).

Montgomery, D. C. Diseño y Análisis de Experimentos. Grupo Editorial Iberoamérica. 585 pp. (1991).

Miller, R. G. Jr. Simultaneous Statistical Inference, New York Springer-Verlag (1981).

Di Rienzo, J. A. et al. InfoStat versión 2014. Grupo InfoStat, FCA, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina. Available at http://www.infostat.com.ar (2014).

Hammer, Ø., Harper, D. A. T. & Ryan, P. D. PAST-PAlaeontological STatistics, ver. 1.89. Palaeont. Electr. 4, 1–9 (2001).

Fry, J. C. & Davies, A. R. An assessment of methods for measuring volumes of planktonic bacteria, with particular reference to television image analysis. J. Appl. Microbiol. 58, 105–112 (1985).

Kang, S. H. et al. Antarctic phytoplankton assemblages in the marginal ice zone of the northwestern Weddell Sea. J. Plankton Res. 23, 333–352 (2001).

Von Harbou, L. et al. Salps in the Lazarev Sea, Southern Ocean: I. Feeding dynamics. Mar. Biol. 158, 2009–2026 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This project benefited from the financial support of PICT-Raíces 2011–1320 to IS, the Total Foundation (ECLIPSE Project). It has been additionally supported by the European Commision under the 7th Framework Programme through the Action – IMCONet (FP7 IRSES, action no. 319718). It is a contribution to the Coastal Ecology Monitoring programme of Instituto Antártico Argentino/Dirección Nacional del Antártico in Carlini Station and the research program PACES II (topic 1, workpackage 5) of the Alfred Wegener Institute. We are very thankful to the logistic support and the overwintering personnel in Carlini Station and to G. Ferreyra and G. Winkler (ISMER), K. Schmidt (BAS), E.-M. Nöthig and D. Abele (AWI), G. B. Esnal (University Buenos Aires, Argentina), J. Movilla and A. Olariaga (CSIC-ICM). G.E.A. was financed by the German Academic Exchange Service and the Argentine Ministry of Education. G. Alurralde was financed by the ECLIPSE Project (supported by the Total Foundation) and by IMCONet.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.F. first observed krill stranding events, planned the subsequent fieldwork and analysed the data. Together with G.A., G.E.A. and B.M. they performed the feeding, and absorption experiments and analysed the stomach contents of krill. A.C. analysed the data and performed statistic tests while contributing to the overall discussion. A.C.W. and H.C.H. contributed with the information related to glacier and particle dynamics. G.W. analysed the data and provided satellite images. I.R.S. analysed the environmental data, integrated all the information and wrote the paper. All authors have further contributed in writing the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Fuentes, V., Alurralde, G., Meyer, B. et al. Glacial melting: an overlooked threat to Antarctic krill. Sci Rep 6, 27234 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep27234

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep27234

This article is cited by

-

Keystones of green smart city—framework, e-waste, and their impact on the environment—a review

Ionics (2023)

-

Can heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) serve as biomarkers in Antarctica for future ocean acidification, warming and salinity stress?

Polar Biology (2022)

-

Glacial melt disturbance shifts community metabolism of an Antarctic seafloor ecosystem from net autotrophy to heterotrophy

Communications Biology (2021)

-

Successful ecosystem-based management of Antarctic krill should address uncertainties in krill recruitment, behaviour and ecological adaptation

Communications Earth & Environment (2020)

-

Plankton or benthos: where krill belongs in Spitsbergen fjords? (Svalbard Archipelago, Arctic)

Polar Biology (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.