Abstract

Topological defects (TDs) appear almost unavoidably in continuous symmetry breaking phase transitions. The topological origin makes their key features independent of systems’ microscopic details; therefore TDs display many universalities. Because of their strong impact on numerous material properties and their significant role in several technological applications it is of strong interest to find simple and robust mechanisms controlling the positioning and local number of TDs. We present a numerical study of TDs within effectively two dimensional closed soft films exhibiting in-plane orientational ordering. Popular examples of such class of systems are liquid crystalline shells and various biological membranes. We introduce the Effective Topological Charge Cancellation mechanism controlling localised positional assembling tendency of TDs and the formation of pairs {defect, antidefect} on curved surfaces and/or presence of relevant “impurities” (e.g. nanoparticles). For this purpose, we define an effective topological charge Δmeff consisting of real, virtual and smeared curvature topological charges within a surface patch Δς identified by the typical spatially averaged local Gaussian curvature K. We demonstrate a strong tendency enforcing Δmeff → 0 on surfaces composed of Δς exhibiting significantly different values of spatially averaged K. For Δmeff ≠ 0 we estimate a critical depinning threshold to form pairs {defect, antidefect} using the electrostatic analogy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Continuous symmetry breaking phase transitions are ubiquitous and are the main reason behind the rich diversity of patterns observed in nature. In phase transitions topological defects (TDs)1 unavoidably appear at least temporarily in a relevant field describing the ordering of the broken phase. Due to topological reasons, physics of TDs features several universalities which are of interest for all branches of physics, spanning particle physics, condensed matter and even cosmology. For example, the first theory of coarsening of TDs following a phase transition quench, was developed in cosmology2 to describe TDs in the Higgs field within the early universe. On the other hand, the most experimentally amenable system to study static and dynamic properties of TDs are various liquid crystalline (LC) structures3. In addition to fundamental science, the ability to sensitively control and tame TDs is also of high interest in various technological and biomedical applications4,5,6.

Structures of symmetry broken phases are determined by the gauge field1,7 component of a relevant order parameter pertinent to the phase transition. On the other hand, the degree of established ordering is quantified by its amplitude. If a gauge field is topologically frustrated, topological defects are introduced to intervene between regions imposing competing gauge field structures. The volume enclosing a TD, where the amplitude of the order parameter is substantially suppressed responding to local strong elastic distortions, is referred to as the core7,8 of the TD. In general, in the core’s centre i) the higher symmetry phase ordering is topologically trapped9 and ii) the gauge field is not uniquely defined. The key property of a TD is quantified by the discrete topological charge q, which is an additive and a conserved quantity1. An isolated topological defect bears q ≠ 0 and can not be removed via local continuous transformations. One commonly refers to TDs with a positive and a negative value of q as defect and antidefect, respectively. In general, the presence of TDs is energetically costly and systems tend to avoid them. Consequently, in most cases a nearby pair {defect, antidefect} mutually annihilates into a locally defectless structure. The Goldstone-type excitations in the gauge field component, which are a direct consequence of broken continuous symmetry, potentially enable an effective long range interaction of TDs with their neighbourhood7,10. Therefore, gauge fields determine the “sight” of TDs via which they could efficiently probe nearby conditions. On the other hand, controlled variations of gauge fields could be exploited to manipulate the position, assembling and even the number of TDs.

An experimentally adequate and accessible testing bed to analyse structures of TDs in orientational degrees of freedom are effectively two-dimensional soft films possessing in-plane ordering. Among them are of particularly hot recent interest liquid crystalline shells11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18 and biological membranes19,20,21,22. Henceforth, we refer to them as ordered soft films. The former systems typically consist of a fluid droplet carrier covered by a thin (few molecular lengths) liquid crystalline film. They are promising candidates for various future photonic applications11,23. Furthermore, in biological membranes TDs could serve as nucleating sites for diverse biological mechanisms. For example, they could enable anomalous growth or even facilitate cell fission22.

These ordered soft films could be mathematically treated as an effectively two-dimensional system, where the charge q of a TD is equivalent3 to its winding number m. 2D XY-type minimal models have been commonly used to study TDs in such geometries. Pioneering studies on frozen surfaces24,25,26,27 reveal that the Gaussian curvature K strongly impacts the position and number of TDs. The Poincaré-Hopff and Gauss-Bonnet theorems28 claim that the total topological charge of TDs within a closed surface possessing in-plane order is determined by the total surface integral of K. It has been shown24,25 that electrostatic analogy could be employed to describe the coupling between K and m. In this analogy K and topological charges play the role of an electric field and electric charges24,25, respectively. It has been demonstrated that surfaces exhibiting regions with both positive and negative K could trigger the unbinding24,25 of pairs of TDs bearing opposite topological charges. The majority of these studies23,24,25,26,27 were based on a covariant derivative approach, which takes into account only the so called intrinsic curvature contributions. In case of in-plane orientational order, these terms penalise departures of the ordering field from surface geodesics. However, latter works by Selinger et al.29,30 and Napoli and Vergori31,32 demonstrated that the so-called extrinsic terms should be also considered and their contribution is reminiscent to an external ordering field. In general, extrinsic and intrinsic terms might enforce contradicting tendencies29,31. The extrinsic term is also related to a deviatoric term introduced in the study of anisotropic biological membranes and thin shells20,21,33,34.

In addition, several recent studies in LCs reveal strong interactions between TDs and nanoparticles (NPs)6,35,36,37,38,39. In case that NPs do not interact with the nematic director field (i.e. the gauge field describing the nematic orientational ordering) exhibiting TDs then the NPs often tend to assemble within cores of TDs. However, if a NP strongly interacts with a nematic director field, it could effectively act as a topological charge35,18. In such cases NPs could change the total topological charge of “real” TDs in the system18.

In our contribution we study the impact of K and NPs, effectively acting as TDs, on the number and position of TDs within the ordered soft films exhibiting nematic-type in-plane ordering. We use a Landau-de Gennes-Helfrich type model40,41,42,43 formulated in terms of a 2D nematic order tensor Q and surface curvature tensor C. We introduce the Effective Topological Charge Cancellation mechanism exploiting the electrostatic analogy. It predicts assembling tendencies of TDs on surfaces possessing surface patches with significantly different values of K. Based on it, we estimate the threshold condition for curvature driven formations of pairs {defect, antidefect} on demonstrative geometries.

Results

We study the nematic ordering on closed, smooth, axially symmetric surfaces. Liquid crystal molecules are bound to lie on the local tangent plane on a surface locally described by the outer unit normal v, but are otherwise unconstrained. Local surface curvature is described by the curvature tensor

Its unit eigenvectors {e1, e2} determine the directions of maximal and minimal curvature, eigenvalues {C1, C2} are the corresponding principal curvatures and v = e1 × e2. Key invariants formed by C are the Gaussian curvature K = C1C2 and the mean curvature H = (C1 + C2)/2. Alternatively, the invariant can be also the curvature deviator D = (C1 − C2)/221,33,34, where D2 = H2 − K.

To describe the orientational ordering on a surface, we introduce a surface order tensor Q. In the diagonal form it can be expressed as42,43

where {n, n⊥} are the eigenvectors of Q corresponding to the eigenvalues of {λ, −λ}, λ ∈ [0, 1/2]. The lower bound (λ = 0) corresponds to the isotropic state, where the orientational order is lost, while the upper bound (λ = 1/2) corresponds to the maximal degree of the orientational order. In general, n is classified as a gauge field and is in LC community commonly referred to as the nematic director field. Topological defects are signalled by λ = 0.

The total free energy functional of the ordered soft film surface ζ is expressed as an integral of the sum of the ordered soft film isotropic bending energy density (fb), orientational condensation contribution (fc) and elastic orientational free energy density (fe)42,43:

where d2r is an infinitesimal surface element and the integration is carried out over the whole ordered soft film surface area ζ. The free energy density contributions are expressed as

The isotropic bending energy density of a membrane (Eq. (4)) is described within the isotropic spontaneous curvature membrane model40,41,44,45,46, where κ is the membrane bending constant and C0 is the isotropic membrane spontaneous curvature34.

The condensation term enforces the equilibrium nematic ordering amplitude  , α = (Tc − T)α0, α0 and β stand for positive Landau expansion material dependent coefficients and Tc is the phase transition temperature.

, α = (Tc − T)α0, α0 and β stand for positive Landau expansion material dependent coefficients and Tc is the phase transition temperature.

The orientational (anisotropic) elastic terms are described by positive intrinsic (ki) and extrinsic (ke) elastic constants, weighting relative importance of intrinsic and extrinsic (deviatoric) elastic contributions20,21,29,30,31,32,33,34. The intrinsic elastic component is associated with variations of n living in 2D curved space. On the other hand, the extrinsic elastic component tells how n is embedded in 3D space. The difference between these contributions is well visible in an infinitely long cylinder of radius R. The intrinsic elastic penalty equals to zero for n, pointing either along the symmetry axis or at right angles with it. However, the extrinsic term is non-zero and it favours n to align along the symmetry axis. Details are presented in Supplementary Material. The essential characteristic material dependent length of the model is the order parameter correlation length  , where k is an effective representative nematic elastic constant. In cases dominated by the intrinsic curvature it holds k ~ ki.

, where k is an effective representative nematic elastic constant. In cases dominated by the intrinsic curvature it holds k ~ ki.

In the study we consider either elliptical or dumb-bell shaped closed ordered soft films of surfaces ζ exhibiting spherical topology. We set ζ as surfaces of revolution with rotational symmetry about the z–axis within the Cartesian system (x, y, z) defined by the unit vectors triad (ex, ey, ez). Ellipsoidal shapes are parameterised as42

Here, r is the position vector of a generic point lying on an ellipsoid surface ζ, v ∈ [0, π] and u ∈ [0, 2π] stand for zenith and azimuthal angles; 2a is the height and 2b the width of an ellipsoid. The ellipsoidal films are prolate (oblate) when η = a/b > 1 (η < 1). On the other hand, dumb-bell structures are calculated within the spontaneous curvature model. Calculation details are presented in Methods.

Effective Topological Charge Cancellation mechanism

Let us suppose that a closed surface ζ consists of surface patches Δζ, where each patch is characterised by a significantly different average Gaussian curvature  . Within each patch Δζ we introduce the effective topological charge

. Within each patch Δζ we introduce the effective topological charge

consisting of real (Δm), virtual (Δmv) and smeared curvature (ΔmK) topological charge. They are defined as follows: Δm and Δmv represent sums of topological charges of “real” and “virtual” TDs within a patch, respectively. A “real” topological charge displays a singularity in n in the centre of TD’s core. On the other hand, a “virtual” TD is formed by an “object” (e.g. a μm or a nano-sized particle)35 immersed in a LC film, which at the object-LC interface enforces a nematic director field resembling a “real” TD as illustrated in Figure S4 in Supplementary Material section. Finally, in spirit of the known fact that local positive (negative) Gaussian curvature acts like a smeared negative (positive) topological charge24,25, we define ΔmK as

We claim, that within each patch Δζ there is a “neutralisation” tendency to cancel the effective topological charge within it (i.e. to form a local configuration exhibiting Δmeff (Δζ) = 0), to which we refer as the Effective Topological Charge Cancellation (ETCC) mechanism. We term a structure, in which Δmeff (Δζ) ~ 0 (i.e. Δmeff ≪ m0) is fulfilled in each patch, the ETCC limit structure. Here m0 represents the smallest unit TD charge, which in nematic LCs equals to m0 = 1/2. Note, that the effective topological charge of any whole closed surface ζ equals to zero. Namely, according to the Gauss-Bonnet and Poincaré-Hopff theorems28, the total topological charge of an in-plane orientational field is given by

In terms of our definitions it holds  , yielding Δmeff (ζ) = 0.

, yielding Δmeff (ζ) = 0.

In the following paragraphs, we demonstrate the ETCC mechanism neutralisation tendency within patches Δζ numerically on several examples. In cases Δmeff (Δζ) ≠ 0 the system i) aims either to globally redistribute existing TDs or ii) exhibits the tendency to form additional pairs {defect, antidefect} in order to “neutralise” the effective topological charge. We also show that the mechanism enables estimation of threshold conditions to form pairs {defect, antidefect}.

Defect-antidefect depinning threshold

In general, ETCC limit structures could be formed either via i) redistribution of TDs or ii) formation of additional TDs obeying the conservation of the total topological charge in the system. In the following paragraphs, we represent key features of the latter case. We analytically estimate the threshold condition for a depinning of pairs {defect, antidefect} based on the ETCC mechanism on a relatively simple demonstrative case. In recent reports24,25,47 it has been demonstrated that curvature could trigger depinning for surfaces exhibiting both positive and negative Gaussian curvature. Below, we demonstrate that depinning could be enforced also on surfaces where spatially dependent K does not change the sign.

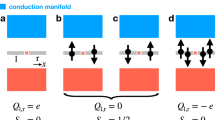

To illustrate the universality of the mechanism we consider i) surfaces composed of regions exhibiting K > 0 and K < 0 and also ii) surfaces exhibiting only  . Schematic sketches of (ellipsoidal and dumb-bell) shapes considered in our simulations and corresponding typical spatial variations of K are depicted in Fig. 1a–c.

. Schematic sketches of (ellipsoidal and dumb-bell) shapes considered in our simulations and corresponding typical spatial variations of K are depicted in Fig. 1a–c.

Schematic representation of closed shells and their electrostatic analogue.

(a) prolate ellipsoid, (b) oblate ellipsoid, (c) dumb-bell shape. Typical spatial variation of the Gaussian curvature is depicted at the right side of these shapes. (d) The electrostatic analogue of structures. The capacitor plates located at ρ1 and ρ2 host effective topological charges Δmeff (Δζ+) > 0 and Δmeff (Δζ−) < 0, respectively, where |Δmeff (Δζ−)| = Δmeff (Δζ+).

For sake of clarity, in presenting the mechanism we henceforth limit our attention only to structures exhibiting inversion symmetry in the absence of the extrinsic field. For symmetry reasons we limit our attention to orientational ordering within upper halves of structures shown in Fig. 1a–c. Within them we introduce two competing surface patches Δζi characterised by significantly different values of Ki = K (Δζi). Here i = {+, −} designates the surface patch bearing a {positive, negative} effective topological charge. Due to the Poincaré-Hopff and Gauss-Bonnet theorems, it holds Δmeff (Δζ+) + Δmeff (Δζ−) = 0, therefore

In Fig. 1a–c these competing patches are separated by thick dash-dotted lines, characterised by K = K0. In structures possessing both signs of Gaussian curvature it is natural to set K0 = 0. For ellipsoids, we set K0 = 〈K〉, where 〈K〉 describes the average value of K on a closed surface ζ. In the latter case, K0 separates the competing surface patches exhibiting K ~ 0 and K ≫ 0.

We consider cases where  and we employ a two-dimensional electrostatic analogy originally suggested by Bowick et al.24. Within this analogy a monopole bearing charge m creates the elastic electric field

and we employ a two-dimensional electrostatic analogy originally suggested by Bowick et al.24. Within this analogy a monopole bearing charge m creates the elastic electric field

representing the elastic analogue of a 2D electric field, where details are given in the Supplementary Material. Here kF is a representative elastic constant and ρ stands for the distance from the monopole.

In this view, the upper parts of configurations shown in Fig. 1a–c are roughly analogous to a 2D cylindrical capacitor schematically sketched in Fig. 1d. The two concentric capacitor plates are located at radii ρ = ρ1 and ρ = ρ2, where the inner and outer plate bear effective charges  and

and  , respectively. Here ρ1 (ρ2) defines the radius of the “mass-point” of positive (negative) effective topological charge spatial distribution.

, respectively. Here ρ1 (ρ2) defines the radius of the “mass-point” of positive (negative) effective topological charge spatial distribution.

To estimate critical conditions for which a stable pair {defect, antidefect} bearing unit topological charges {1/2, −1/2} is created driven by the ETCC mechanism, we calculate the total energy ΔF needed for this process. The critical condition is inferred from the requirement ΔF = 0, where penalties of forming the TDs are compensated by gains due to at least partially cancelled Δmeff. The critical condition reads

where details are given in the Supplementary Material.

Numerical results

In this subsection we illustrate numerically the ETCC mechanism on simple demonstrative closed shapes exhibiting a spherical topology. The mechanism is particularly pronounced for cases where the intrinsic elastic free energy contributions are dominant, corresponding in our modelling to ki ≫ ke. For this purpose we set ke = 0 in the main part of our study.

We first consider the ellipsoidal shapes. Of interest to us is the impact of the spatially dependent K and NP-induced virtual topological charge on the position and number of TDs. We impose the spatially dependent K by varying the ratio η = a/b of the ellipsoids, see Eq. (7). In addition to reference configurations with Δmv = 0 we also analyse structures containing a different number of spatially fixed circular NPs of the radius  , where each nanoparticle effectively acts as a topological defect bearing m = 1. Experimentally, such conditions could be realised by enforcing homeotropic anchoring at the NP’s interface35 (i.e. the molecules tend to be aligned along the NP’s surface normal). In Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Material, we illustrate predetermined positions of NPs used in simulations on the case of spherically shaped ordered soft films. These configurations possess either i) one (Fig. S1b), ii) two (Fig. S1c) or iii) three NPs (Fig. S1d). The centres of NPs are placed at i) (u1 = 0, v1 = π/2), ii) (u1 = 0, v1 = π/2), (u2 = 0, v2 = 0), iii) (u1 = 0, v1 = π/2), (u2 = 0, v2 = 0), (u3 = 0, v3 = π), where (ui, vi) locates the position of the i-th NP, see Eq. (7).

, where each nanoparticle effectively acts as a topological defect bearing m = 1. Experimentally, such conditions could be realised by enforcing homeotropic anchoring at the NP’s interface35 (i.e. the molecules tend to be aligned along the NP’s surface normal). In Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Material, we illustrate predetermined positions of NPs used in simulations on the case of spherically shaped ordered soft films. These configurations possess either i) one (Fig. S1b), ii) two (Fig. S1c) or iii) three NPs (Fig. S1d). The centres of NPs are placed at i) (u1 = 0, v1 = π/2), ii) (u1 = 0, v1 = π/2), (u2 = 0, v2 = 0), iii) (u1 = 0, v1 = π/2), (u2 = 0, v2 = 0), (u3 = 0, v3 = π), where (ui, vi) locates the position of the i-th NP, see Eq. (7).

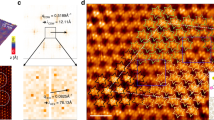

Possible ETCC limit structures enforced by the electrostatic-analogy based ETCC mechanism, which is effective for η ≠ 1, are plotted in the (b) and (c) row of Fig. 2. The Δζ− (Δζ+) surface patches are coloured with white (grey) color. The corresponding representative simulation results are assembled in Figs 3 and 4. In Fig. 3 we plot λ(u, v) dependences, from which we infer the positions of TDs. Namely, in the centre of a TD’s core, the degree of order is melted, i.e λ = 0. In the (a) column of Fig. 3, we plot the reference configurations calculated for spherical ordered soft films, while structures reached for relatively strongly oblate or prolate ellipsoids, for which ETCC limit structures are realised, are shown in the columns (b) and (c), respectively. In Fig. 4 we trace the zenith angular positions vd of TDs on varying η, revealing how ETCC limit structures are formed.

Calculated order parameter profiles in the (u, v) plane of the ellipsoidal shells.

Column (a): spherical shapes, a/b = 1.0; Column (b): oblate shapes, a = R and (I) b/a = 1.5, (II) b/a = 1.5, (III) b/a = 2.0, (IV) b/a = 2.0; Column (c): prolate shells, b = R and (I) a/b = 7.0, (II) a/b = 5.0, (III) a/b = 4.5, (IV) a/b = 3.0. Black circles and ellipses indicate shell shapes. Nanoparticles are labelled NP. Nematic ordering was calculated for: R/ξ = 3.5, ke= 0, R = min{a, b}.

Trajectories of topological defects as the functions of η = a/b.

By vd we denote the v coordinate of the defect origin and by v1/4 the point to which the surface integral of the Gaussian curvature from the equator divided by 2π equals 1/4 mtot. Cases with (a) one, (b) two and (c) three nanoparticles are presented. R/ξ = 3.5, ke = 0, R = min{a, b}.

We first describe the typical patterns of TDs in ellipsoids in the absence of NPs. Note that such configurations have already been studied in detail in13,23,42. Spherical ordered soft films exhibit in equilibrium four m = 1/2 as shown in Fig. 3a, line (i). On the surface of a sphere with radius R the Gaussian curvature is constant and equals K = 1/R2. Therefore, the position of TDs is dominated by their mutual repulsion. In order to maximise their separation they reside in vertices of a hypothetical inscribed tetrahedron23. For η ≠ 1 the Gaussian curvature becomes spatially dependent. In each ellipsoid, two types of different patches {Δζ−, Δζ+} emerge as discussed in the above subsection. Note that the Δζ− (Δζ+) patch attracts TDs bearing m > 0 (m < 0). For oblate (prolate) structures Δζ+ patches are located at the poles (equatorial band) of structures and are characterised by  . Therefore, in the limit of strong oblateness TDs are assembled roughly along the equatorial line in order to compensate for ΔmK (Δζ−) < 0, see Fig. 3b, line (i). The equatorial line K exhibits maximal value and therefore acts as an attractor for TDs. In strongly prolate structures TDs are pushed towards the poles for the same reason. In the case shown in Fig. 3c, line (i), the characteristic Δζ− region is strongly localised at the poles and consequently two m = 1/2 TDs merged into a single TD exhibiting m = 1.

. Therefore, in the limit of strong oblateness TDs are assembled roughly along the equatorial line in order to compensate for ΔmK (Δζ−) < 0, see Fig. 3b, line (i). The equatorial line K exhibits maximal value and therefore acts as an attractor for TDs. In strongly prolate structures TDs are pushed towards the poles for the same reason. In the case shown in Fig. 3c, line (i), the characteristic Δζ− region is strongly localised at the poles and consequently two m = 1/2 TDs merged into a single TD exhibiting m = 1.

Next, we treated cases possessing one NP bearing m = 1 as depicted in Fig. S1b. In a sphere two m = 1/2 TDs are present, yielding mtot = 2, see Fig. 2a, line (i) and Fig. 3a, line (ii). The spatial distribution of TDs is dominated by repulsion among real and virtual topological charges, tending to maximise their mutual separation. On increasing the oblateness the two TDs progressively approach the equatorial line as shown in Fig. 4a, for which an ETCC limit structure is realised (see also Fig. 2b, line (i); Fig. 3b. line (ii)). By contrast, on increasing the prolateness an ETCC limit structure could not be realised via the existing set of virtual and real TDs present in the spherical geometry. In this case, two pairs {defect, antidefect} = {m = 1/2, m = −1/2} must be formed. The two antidefects are needed to screen the central virtual charge enforced by NP. On the other hand, defects are moved toward the poles. The corresponding ETCC limit structure is shown in Fig. 2c. line (i) (schematic sketch) and Fig. 3c, line (ii) (simulation). The spatial evolution of TDs and the triggering of pairs {defect, antidefect} on increasing η are shown in Fig. 4a.

If two NPs bearing m = 1 are present, see Fig. S1c, topological requirements do not necessitate the presence of “real” TDs. However, even in spherical geometry a pair {defect, antidefect} is created as demonstrated in Fig. 3a, line (iii), which can be explained roughly using an electrostatic analogy (Supplementary Material). In the oblate ETCC limit structure an additional pair {defect, antidefect} is formed, which enables the cancellation of effective topological charges in all surface patches as sketched in Fig. 2b, line (ii). The corresponding numerically obtained texture is shown in Fig. 3b, line (iii). One sees that the two antidefects move towards the upper pole to screen the NP’s virtual topological charge. By contrast, the defects assemble in the equatorial region and together with the central NP’s virtual topological charge compensate for the curvature topological charge. To form the prolate ETCC limit structure, a pair {defect, antidefect} also needs to be formed. However, in this case the antidefects assemble in the equatorial region to compensate for the NP’s virtual topological charge, see Fig. 2c, line (ii) and Fig. 3c, line (iii). On the other hand, the two defects assemble (and in the case studied even merge) at the bottom pole of the ellipsoid to cancel the negative curvature charge. The variations of the zenith positions of TDs and the creation of new pairs of TDs on varying η spanning an oblate and prolate ETCC limit structure are shown in Fig. 4b.

We proceed by studying configurations possessing 3 NPs (see Fig. S1d). To obey the Poincaré-Hopff and Gauss-Bonnet theorems, two antidefects are introduced in the spherical geometry. The formed structure is again understood by an electrostatic analogy. Both antidefects assemble close to the central NP and effectively neutralise its charge (see Fig. 2a, line (iii) and Fig. 3a, line (iv)). Therefore, in the resulting structure only the repulsive interaction between positive virtual charges at opposite poles remains. This configuration of TDs also persists in prolate structures (Fig. 2c, line (iii) and Fig. 3c, line (iv)), because it fulfils the ETCC mechanism tendency. By contrast, to realise oblate ETCC limit structures two pairs {defect, antidefect} need to be formed (see Fig. 2b, line (iii) and Fig. 3b, line (iv)) to compensate for the effective topological charge in each characteristic surface patch. Therefore, at each pole the virtual topological charge is compensated by two antidefects. On the other hand, the curvature topological charge of the equatorial region is compensated by two defects and the central NP’s virtual topological charge. The corresponding spatial variations of TDs on varying η are depicted in Fig. 4c.

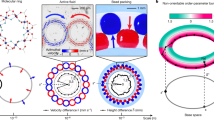

We further demonstrate the curvature driven depinning of a pair {defect, antidefect} on the case of a dumb-bell shaped ordered soft film (see Fig. 5c). Different vesicle shapes were calculated within the spontaneous curvature model (i.e. we neglected the contributions of fc and fe in Eq. (3)) on varying the ratio σ = V/V0 and the membrane spontaneous curvature C0. Here, V determines the vesicle’s volume and V0 stands for the volume of the sphere exhibiting the same surface area. In the simulations, we started from a spherical vesicle, corresponding to σ = 1. In this geometry, the ordered soft film exhibits four TDs bearing m = 1/2 (see Fig. 3a, line (i)). On decreasing σ, a dumb-bell vesicle shape with an increasing ratio μ = ρ2/ρ1 (see Fig. 5c) is gradually formed. Note also that C0 is adequately adjusted in order to obtain shapes with inversion symmetry. The corresponding growth of  (μ) is depicted in the inset of Fig. 5d, where we split the upper part of a vesicle into two surface patches, characterised by K > 0 and K < 0. For a strong enough curvature in the neck area, two pairs {defect, antidefect} are formed due to the ETCC mechanism. In our simulations the transition occurs at the critical value μc = 3.06 ± 0.01, where order parameter profiles in the (u, s) plane just below and above the threshold are plotted in Fig. 5a,b, respectively. Here, s is the arc length of the profile curve characterising axial-symmetric shapes (see Methods). The shape shown in Fig. 5c is calculated at the depinning threshold. In Fig. 5d we analyse our estimate derived based on the electrostatic analogy (see Eq. (13)). We plot the penalty (

(μ) is depicted in the inset of Fig. 5d, where we split the upper part of a vesicle into two surface patches, characterised by K > 0 and K < 0. For a strong enough curvature in the neck area, two pairs {defect, antidefect} are formed due to the ETCC mechanism. In our simulations the transition occurs at the critical value μc = 3.06 ± 0.01, where order parameter profiles in the (u, s) plane just below and above the threshold are plotted in Fig. 5a,b, respectively. Here, s is the arc length of the profile curve characterising axial-symmetric shapes (see Methods). The shape shown in Fig. 5c is calculated at the depinning threshold. In Fig. 5d we analyse our estimate derived based on the electrostatic analogy (see Eq. (13)). We plot the penalty ( , dashed red line (ρ2/ξ = 3.5), dotted dashed blue line (ρ2/ξ = 7)) and gain (

, dashed red line (ρ2/ξ = 3.5), dotted dashed blue line (ρ2/ξ = 7)) and gain ( , full line) contributions on increasing ρ2/ρ1. The crossing of the lines corresponds to the critical condition. In this estimate we set that ρ2 (ρ1) is equal to the maximal (minimal) radius of the structure in the azimuthal plane. Using the calculated

, full line) contributions on increasing ρ2/ρ1. The crossing of the lines corresponds to the critical condition. In this estimate we set that ρ2 (ρ1) is equal to the maximal (minimal) radius of the structure in the azimuthal plane. Using the calculated  , the estimate (Eq. (13)) yields μc = 4 ± 1.5 which is in rough agreement with the numerically obtained result.

, the estimate (Eq. (13)) yields μc = 4 ± 1.5 which is in rough agreement with the numerically obtained result.

Depinning threshold in dumb-bell configurations.

Panels (a,b) show nematic ordering in the (u, s) plane just below and above the threshold calculated for ρ2/ξ = 7, ke = 0. Here, s is the arc length of the profile curve (see Eq. (14)). The shape, calculated at the threshold, is presented in panel (c), where ρ0 determines the value of ρ(s) where K = 0. In panel (d) we plot the penalty Δf (p) (left-hand side of Eq. (13), dashed red line (ρ2/ξ = 3.5), dotted dashed blue line (ρ2/ξ = 7)) and gain Δf (g) (right-hand side of Eq. (13), full line) contributions as the functions of ρ2/ρ1. In the inset we plot  as the function of ρ2/ρ1. Squares reveal points for which

as the function of ρ2/ρ1. Squares reveal points for which  was calculated and the full line is obtained as the corresponding best fit.

was calculated and the full line is obtained as the corresponding best fit.

Conclusions

We studied theoretically and numerically the impact of the Gaussian curvature on the position and number of topological defects in 2D nematic orientational ordering. We introduced the effective topological charge Δmeff in surface patches characterised by a distinctive spatially averaged Gaussian curvature  . We demonstrated the tendency Δmeff (Δζ) → 0 in each patch, to which we refer as the ETCC limit structure. The effectiveness of the Effective Topological Charge Cancellation (ETCC) mechanism increases with the increasing value of |Δmeff| and becomes apparent when |Δmeff| becomes comparable with the unit topological charge m0 of the system (in our case m0 = ±1/2). The mechanism is most evident for systems exhibiting weak extrinsic elasticity. The impact of the latter is demonstrated in Figure S3 in the Supplementary Material.

. We demonstrated the tendency Δmeff (Δζ) → 0 in each patch, to which we refer as the ETCC limit structure. The effectiveness of the Effective Topological Charge Cancellation (ETCC) mechanism increases with the increasing value of |Δmeff| and becomes apparent when |Δmeff| becomes comparable with the unit topological charge m0 of the system (in our case m0 = ±1/2). The mechanism is most evident for systems exhibiting weak extrinsic elasticity. The impact of the latter is demonstrated in Figure S3 in the Supplementary Material.

The ETCC mechanism could be exploited for a controlled positional targeting of TDs to predetermined locations. This property could be exploited in various photonic materials. For example, by changing a local curvature, a local property of such a medium could be dramatically changed by dragging TDs in or out, which could be exploited for local information manipulation. Furthermore, TDs in general efficiently trap various NPs owing to the Defect Core Replacement mechanism4,37. That is to say, if NPs do not strongly locally disrupt the gauge (in our studythe nematic director) field, which exhibits TDs, then NPs tend to assemble within the cores of TDs. In such a way the condensation penalty of a relatively expensive core is reduced. Therefore, via TDs, one could positionally control trapped NPs, which could act as carriers of additional material or a functional property of the system. The manipulation of TDs and NPs could also be exploited for various self-assembling strategies. For example, as suggested by Nelson11, objects studied in our work might be exploited as meta-atoms with a self-assembling ability to form crystal-like structures within isotropic fluids containing nano-binders. In this case, TDs determine the “valence” of meta-atoms because of their potential ability to efficiently locally pin nano-binders. Via them nearby meta-atoms could be physically bonded. Controlling the positions and the number of TDs in such shells is expected to enable a self-assembling of meta-atoms into crystal configurations with almost arbitrary symmetries. Note that symmetry often imposes a dominant impact on the effective physical properties of materials.

Methods

In simulations, we calculated the nematic ordering for a chosen geometry of a closed two-dimensional surface. For demonstrative purposes we considered axial-symmetric shells with inversion symmetry. We assumed that the elastic costs of bending shells are large with respect to elastic costs related to deformations in the orientational degree of order. We considered either ellipsoidal shells using Eq. (7) or dumb-bell shaped shells calculated using the spontaneous curvature model. We first summarised the main ingredients of the spontaneous curvature model. Afterwards, we described the 2D Landau-de Gennes approach by which the orientational ordering was calculated for a given shell geometry.

Calculation of shapes

In generating shell shapes calculated within the spontaneous curvature model, we introduce arc length s of the profile curve and angle ϕ (s), which represents the angle of the tangent to the profile curve with the plane that is perpendicular to the axis of rotation ez. The shell profile curve is calculated by48:

where ρ(s) and z (s) are the coordinates of the profile in the (ρ, z)-plane. The surface of the shell is constructed by the rotation of the profile curve about the ez axis by an angle of u = 2π. For closed and smooth surfaces, we have to apply the following boundary conditions: ϕ(0) = 0, ϕ(Ls) = π and ρ(0) = ρ(Ls) = 0, where Ls is the profile length. The function describing the angle ϕ(s) is approximated by the Fourier series48,

where N is the number of Fourier modes, ai are the Fourier amplitudes and ϕ0 is the angle at the north pole of the shell, ϕ0 = ϕ(Ls) = π. The local principal curvatures C1 and C2 are given as  and

and  , respectively. The bending energy density fb (see Eq. (4)) is therefore a function of the Fourier amplitudes ai and the shape profile length Ls. Equilibrium vesicle shapes are calculated by the numerical minimisation of the function of many variables48. In the minimisation procedure, the vesicle surface area and the volume are kept constant.

, respectively. The bending energy density fb (see Eq. (4)) is therefore a function of the Fourier amplitudes ai and the shape profile length Ls. Equilibrium vesicle shapes are calculated by the numerical minimisation of the function of many variables48. In the minimisation procedure, the vesicle surface area and the volume are kept constant.

Calculation of nematic order

We parameterise the nematic order tensor as42,43:

where q0 and qm are scalar functions. We assume that shell surface ζ is a surface of revolution with rotational symmetry about the z-axis within the Cartesian system (x, y, z). We represent the position vector r of a generic point lying on ζ as:

where u ∈ [0, 2π] stands for the azimuthal angle. Eq. (17) represents a general description of an axi-symmetric surface. In our study, we focused on two types of axi-symmetric surfaces. Ellipsoidal surfaces are parameterised by Eq. (7), while the surfaces defined by the profile curve are described by Eq. (14). The following mathematical description of various surface properties is valid for both types of surfaces, although it is adjusted to the surfaces defined by the profile curve.

The standard functions that represent the first fundamental form on surface ζ in the (u, s) coordinates are given by42,49:

where a comma denotes the differentiation and

is the Jacobian determinant. On a surface of revolution parallels and meridians are lines of principal curvature. We define e1 as a unit vector along meridians (u = const) and e2 as a unit vector along parallels (s = const). The meridians are also geodesics, so their geodesic curvature κg1 = 0. The geodesic curvature of the parallels can be written as42,49:

The Gaussian and mean curvatures of the shell surface ζ are42,49:

K and H are connected to the local principal curvatures C1 and C2 via

The surface gradient of scalar function ψ in the coordinates (u, s) on surface ζ is given by:

The surface gradients of e1 and e2 are given by Eqs (S4) and (S5) (see Supplementary Material), respectively. We express the free energy density in terms of fields q0 and qm for a given ordered soft film geometry. The equilibrium textures were calculated either by using the standard Monte Carlo method or by numerically solving the Euler-Lagrange equations42,49. Both methods yield the same results.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Mesarec, L. et al. Effective Topological Charge Cancelation Mechanism. Sci. Rep. 6, 27117; doi: 10.1038/srep27117 (2016).

References

Mermin, N. D. The topological theory of defects in ordered media. Rev. Mod. Phys. 51, 591 (1979).

Kibble, T. W. Topology of cosmic domains and strings. J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 9, 1387 (1976).

Lavrentovich, O. Topological defects in dispersed words and worlds around liquid crystals, or liquid crystal drops. Liq. Cryst. 24, 117–126 (1998).

Kikuchi, H., Yokota, M., Hisakado, Y., Yang, H. & Kajiyama, T. Polymer-stabilized liquid crystal blue phases. Nat. Mater. 1, 64–68 (2002).

Brake, J. M., Daschner, M. K., Luk, Y. Y. & Abbott, N. L. Biomolecular interactions at phospholipid-decorated surfaces of liquid crystals. Science 302, 2094–2097 (2003).

Campbell, M. G., Tasinkevych, M. & Smalyukh, I. I. Topological polymer dispersed liquid crystals with bulk nematic defect lines pinned to handlebody surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 197801 (2014).

Pleiner, H. Dynamics of a disclination point in smectic-c and -c* liquid-crystal films. Phys. Rev. A 37, 3986 (1988).

Zhang, C. et al. Nanostructure of edge dislocations in a smectic-c* liquid crystal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 087801 (2015).

Kibble, T. Phase-transition dynamics in the lab and the universe. Phys. Today 60, 47 (2007).

Kralj, S. & Virga, E. G. Universal fine structure of nematic hedgehogs. J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 34, 829 (2001).

Nelson, D. R. Toward a tetravalent chemistry of colloids. Nano Lett. 2, 1125–1129 (2002).

Fernández-Nieves, A. et al. Novel defect structures in nematic liquid crystal shells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 157801 (2007).

Skačej, G. & Zannoni, C. Controlling surface defect valence in colloids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 197802 (2008).

Liang, H. L., Schymura, S., Rudquist, P. & Lagerwall, J. Nematic-smectic transition under confinement in liquid crystalline colloidal shells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 247801 (2011).

Lopez-Leon, T., Fernandez-Nieves, A., Nobili, M. & Blanc, C. Nematic-smectic transition in spherical shells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 247802 (2011).

Lopez-Leon, T., Koning, V., Devaiah, K., Vitelli, V. & Fernandez-Nieves, A. Frustrated nematic order in spherical geometries. Nat. Phys. 7, 391–394 (2011).

Seč, D. et al. Defect trajectories in nematic shells: Role of elastic anisotropy and thickness heterogeneity. Phys. Rev. E 86, 020705 (2012).

Gharbi, M. A. et al. Microparticles confined to a nematic liquid crystal shell. Soft Matter 9, 6911–6920 (2013).

MacKintosh, F. & Lubensky, T. Orientational order, topology and vesicle shapes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 67, 1169 (1991).

Kralj-Iglič, V., Iglič, A., Hägerstrand, H. & Peterlin, P. Stable tubular microexovesicles of the erythrocyte membrane induced by dimeric amphiphiles. Phys. Rev. E 61, 4230 (2000).

Kralj-Iglič, V., Babnik, B., Gauger, D. R., May, S. & Iglič, A. Quadrupolar ordering of phospholipid molecules in narrow necks of phospholipid vesicles. J. Stat. Phys 125, 727–752 (2006).

Jesenek, D. et al. Vesiculation of biological membrane driven by curvature induced frustrations in membrane orientational ordering. Int. J. Nanomedicine 8, 677–687 (2013).

Vitelli, V. & Nelson, D. R. Nematic textures in spherical shells. Phys. Rev. E 74, 021711 (2006).

Bowick, M., Nelson, D. R. & Travesset, A. Curvature-induced defect unbinding in toroidal geometries. Phys. Rev. E 69, 041102 (2004).

Vitelli, V. & Turner, A. M. Anomalous coupling between topological defects and curvature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 215301 (2004).

Bowick, M. J. & Giomi, L. Two-dimensional matter: order, curvature and defects. Adv. Phys. 58, 449–563 (2009).

Turner, A. M., Vitelli, V. & Nelson, D. R. Vortices on curved surfaces. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 1301 (2010).

Kamien, R. D. The geometry of soft materials: a primer. Rev. Mod. Phys. 74, 953 (2002).

Selinger, R. L. B., Konya, A., Travesset, A. & Selinger, J. V. Monte carlo studies of the xy model on two-dimensional curved surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. B 115, 13989–13993 (2011).

Nguyen, T. S., Geng, J., Selinger, R. L. & Selinger, J. V. Nematic order on a deformable vesicle: theory and simulation. Soft Matter 9, 8314–8326 (2013).

Napoli, G. & Vergori, L. Surface free energies for nematic shells. Phys. Rev. E 85, 061701 (2012).

Napoli, G. & Vergori, L. Extrinsic curvature effects on nematic shells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 207803 (2012).

Kralj-Iglič, V., Remškar, M., Vidmar, G., Fošnarič, M. & Iglič, A. Deviatoric elasticity as a possible physical mechanism explaining collapse of inorganic micro and nanotubes. Phys. Lett. A 296, 151–155 (2002).

Iglič, A., Babnik, B., Gimsa, U. & Kralj-Iglič, V. On the role of membrane anisotropy in the beading transition of undulated tubular membrane structures. J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 38, 8527 (2005).

Poulin, P., Stark, H., Lubensky, T. & Weitz, D. Novel colloidal interactions in anisotropic fluids. Science 275, 1770–1773 (1997).

Muševič, I., Škarabot, M., Tkalec, U., Ravnik, M. & Žumer, S. Two-dimensional nematic colloidal crystals self-assembled by topological defects. Science 313, 954–958 (2006).

Karatairi, E. et al. Nanoparticle-induced widening of the temperature range of liquid-crystalline blue phases. Phys. Rev. E 81, 041703 (2010).

Coursault, D. et al. Linear self-assembly of nanoparticles within liquid crystal defect arrays. Adv. Mater. 24, 1461–1465 (2012).

Silvestre, N. M., Liu, Q., Senyuk, B., Smalyukh, I. I. & Tasinkevych, M. Towards template-assisted assembly of nematic colloids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 225501 (2014).

Deuling, H. J. & Helfrich, W. Red blood cell shapes as explained on the basis of curvature elasticity. Biophys. J. 16, 861–868 (1976).

Helfrich, W. Elastic properties of lipid bilayers: theory and possible experiments. Z. Naturforsch. C 28, 693–703 (1973).

Kralj, S., Rosso, R. & Virga, E. G. Curvature control of valence on nematic shells. Soft Matter 7, 670–683 (2011).

Rosso, R., Virga, E. G. & Kralj, S. Parallel transport and defects on nematic shells. Continuum Mech. Therm. 24, 643–664 (2012).

Evans, E. A. Bending resistance and chemically induced moments in membrane bilayers. Biophys. J. 14, 923–931 (1974).

Shi, Z. & Baumgart, T. Dynamics and instabilities of lipid bilayer membrane shapes. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 208, 76–88 (2014).

Boulbitch, A. et al. Shape instability of a biomembrane driven by a local softening of the underlying actin cortex. Phys. Rev. E 62, 3974 (2000).

Jesenek, D., Kralj, S., Rosso, R. & Virga, E. Soft Matter 11, 2434–2444 (2015).

Gózdz, W. Spontaneous curvature induced shape transformations of tubular polymersomes. Langmuir 20, 7385–7391 (2004).

Do Carmo, M. P. & Do Carmo, M. P. Differential Geometry of Curves and Surfaces, vol. 2 (Prentice-hall Englewood Cliffs, 1976).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support from NCN grant No 2012/05/B/ST3/03302 and the grant of the Slovenian Research Agency (ARRS) No. P–0232 and P1–0099.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.K. initiated this study and developed the theoretical model. L.M. developed a Monte Carlo program and performed the numerical simulations. W.G. developed the numerical procedure for the calculation of shapes, A.I. amended the numerical procedures, S.K., A.I. and L.M. wrote the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Mesarec, L., Góźdź, W., Iglič, A. et al. Effective Topological Charge Cancelation Mechanism. Sci Rep 6, 27117 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep27117

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep27117

This article is cited by

-

Coupling of nematic in-plane orientational ordering and equilibrium shapes of closed flexible nematic shells

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Cationic vacancies as defects in honeycomb lattices with modular symmetries

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Nanoparticle-Stabilized Lattices of Topological Defects in Liquid Crystals

International Journal of Thermophysics (2020)

-

Normal red blood cells’ shape stabilized by membrane’s in-plane ordering

Scientific Reports (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.