Abstract

It is well documented that maternal exposure to second-hand smoke (SHS) during pregnancy causes low birth weight (LBW), but its mechanism remains unknown. This study explored the potential pathways. We enrolled 195 pregnant women who delivered full-term LBW newborns and 195 who delivered full-term normal birth weight newborns as the controls. After controlling for maternal age, education level, family income, pre-pregnant body mass index, newborn gender and gestational age, logistic regression analysis revealed that LBW was significantly and positively associated with maternal exposure to SHS during pregnancy, lower placental weight, TNF-α and IL-1β and that SHS exposure was significantly associated with lower placental weight, TNF-α and IL-1β. Structural equation modelling identified two plausible pathways by which maternal exposure to SHS during pregnancy might cause LBW. First, SHS exposure induced the elevation of TNF-α, which might directly increase the risk of LBW by transmission across the placenta. Second, SHS exposure first increased maternal secretion of IL-1β and TNF-α, which then triggered the secretion of VCAM-1; both TNF-α and VCAM-1 were significantly associated with lower placental weight, thus increasing the risk of LBW. In conclusion, maternal exposure to SHS during pregnancy may lead to LBW through the potential pathways of maternal inflammation and lower placental weight.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Low birth weight (LBW, birth weight <2500 g) may result from preterm birth or intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), which can occur simultaneously in pregnancy1. There is accumulating evidence that LBW is not only the strongest single risk factor for perinatal, neonatal and infant mortality2, but is also related to neurological and behavioural problems in childhood3,4 and chronic diseases in adulthood5,6. Therefore, researchers have started paying attention to studies on the etiological factors associated with LBW and the potential pathophysiological mechanisms.

It is well documented that maternal exposure to second-hand smoke (SHS) is an important risk factor for LBW. A recent meta-analysis estimated that maternal exposure to SHS during pregnancy reduces mean birth weight by 31–60 grams and may increase the risk of LBW by 1.16–1.60 times7. However, the biological mechanisms by which maternal exposure to SHS during pregnancy causes LBW have not been established. A potential pathway may be that maternal exposure to SHS during pregnancy causes maternal inflammation, which disrupts the placenta’s ability to transfer sufficient nutrients and oxygen to the foetus and finally results in LBW.

The aforementioned hypothesis is suggested by the following strands of evidence. First, SHS exposure leads to abnormal levels of inflammatory markers in different populations8,9. Second, the elevated maternal inflammatory markers are independently related to LBW10 and mediate the associations between periodontal disease11, maternal sleep disturbances during pregnancy12, maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI)13 and LBW. Third, the placenta is associated with birth weight and IUGR14,15,16. Fourth, maternal smoking during pregnancy impairs the structure and functioning of the placenta17. Fifth, placental weight partially mediates the effects of prenatal factors such as pre-pregnancy obesity, gestational diabetes mellitus and excessive gestational weight gain on foetal growth18. Sixth, abnormal inflammatory markers have been found in the placentas of LBW cases19.

To the best of our knowledge, there is no research that links the above evidence together to explore the plausible mechanisms. As such, this study aimed to explore the potential pathways that integrate maternal inflammation and the placenta, which might explain the mechanism by which maternal exposure to SHS during pregnancy leads to LBW.

Results

Social-demographic and obstetric characteristics of participants

Table 1 compares the socio-demographic and obstetric characteristics of the full-term LBW and control participants. Apart from their significantly lower birth weight (2343.87 g vs 3300.99 g), full-term LBW infants had a shorter gestational age (38.03 weeks vs 39.08 weeks) and were more likely to be female (59.8% vs 48.2%). Other characteristics, including maternal age, ethnicity, marital status, education level, pre-pregnancy BMI and parity were quite comparable between the full-term LBW cases and the controls.

Associations between maternal exposure to SHS, lower placental weight, maternal serum inflammatory markers and full-term LBW

Table 2 presents the results of the associations between maternal exposure to SHS exposure, lower placental weight, maternal serum inflammatory markers and full-term LBW. After controlling for potential confounders, maternal SHS exposure was significantly and positively associated with lower placental weight (adjusted OR = 2.30; 95% CI = 1.10–4.81), increased maternal TNF-α (adjusted OR = 1.55; 95% CI = 1.06–2.27) and IL-1β (adjusted OR = 1.72; 95% CI = 1.11~2.66). There were also significant and positive associations between lower placental weight and increased maternal TNF-α (adjusted OR = 1.28; 95% CI = 1.01–1.63) and IL-1β (adjusted OR = 1.35, 95% CI = 1.00–1.80).

After controlling for potential confounders, significant positive correlations were observed between MCP-1 and IL-6 (partial relationship, pr = 0.19), IL-6 and CRP (pr = 0.11), TNF-α and IL-1β (pr = 0.25), TNF-α and CRP (pr = 0.12), TNF-α and VCAM-1 (pr = 0.14), IL-1β and CRP (pr = 0.11) and CRP and VCAM-1 (pr = 0.12), whereas significant negative correlations were obtained between IL-6 and TNF-α (pr = −0.14), IL-6 and VCAM-1 (pr = −0.14).

Furthermore, after controlling for potential confounders, full-term LBW was significantly and positively associated with maternal SHS exposure during pregnancy (adjusted OR = 2.14; 95% CI = 1.06–4.32), lower placental weight (adjusted OR = 3.60; 95% CI = 2.09–6.19) and increased maternal serum levels of TNF-α (adjusted OR = 1.92; 95% CI = 1.47–2.50) and IL-1β (adjusted OR = 1.53; 95% CI = 1.14–2.05)

Potential pathways by which maternal SHS exposure during pregnancy causes full-term LBW

The SEM results indicated a good fit to the model (GFI = 0.981, AGFI = 0.947, CFI = 0.988, IFI = 0.989, RMSEA = 0.029). The coefficients in the pathway diagrams indicated that maternal SHS exposure during pregnancy might induce full-term LBW indirectly (Fig. 1). First, maternal SHS exposure during pregnancy led to maternal inflammation by increasing the secretion of TNF-α and IL-1β, which further triggered the secretion of IL-6, CRP and VCAM-1. Second, TNF-α and VCAM-1 in turn affected placental weight. Third, TNF-α and lower placental weight directly affected the full-term LBW.

The potential pathways of maternal secondhand smoke exposure during pregnancy, maternal serum inflammatory markers, placental weight and low birthweight at term.

Note: A one-way arrow linked from influential factor to the response factor. Double headed arrow indicated a correlation between TNF-α and IL-1β Parameters on the path represented direct effects. Only significant effects were kept in this figure and were marked with an asterisk.

The effect of maternal SHS exposure on full-term LBW via each pathway was calculated, as shown in Table 3. There were two indirect pathways, one from IL-β to the placenta (path 2, effect = 0.031, proportion to total effect = 24.2%) and the second from IL-1β to TNF-α (path 3, effect = 0.031, proportion to total effect = 24.2%). Thus, the combined mediation effect of the two pathways was 0.128 and the proportion of the total effect was 48.4% (24.2% + 24.2%).

Discussion

This study tested the hypothesis that maternal SHS exposure during pregnancy leads to full-term LBW through maternal inflammation and lower placental weight. The SEM results showed that maternal exposure to SHS during pregnancy initially induced maternal inflammation by increasing the secretion of IL-1β and TNF-α, which then triggered the secretion of IL-6, CRP and VCAM-1; both TNF-α and VCAM-1 caused a decrease in placental weight; and eventually, TNF-α and the damaged placenta increased the risk of full-term LBW.

Previous studies have reported inconsistent associations between SHS exposure and the six measured inflammatory markers in our study. For example, two studies of male workers reported that SHS exposure was significantly associated with elevated serum CRP9,20, while two further studies in adults8,21 and one in adolescents22 found a non-significant relationship between SHS exposure and serum CRP. Our study showed an insignificant association between maternal SHS exposure during pregnancy and maternal serum CRP levels. Regarding the associations between SHS exposure and three pro-inflammatory markers, IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α, Wilson et al. found that healthy children exposed to SHS had lower serum concentrations of IL-1β than those without SHS exposure23, but an inverse association was observed in adults24 and an insignificant association in adolescents was reported by Matsunaga et al.22. Five studies found that SHS exposure had no significant effect on serum IL-6 in adolescents22,23 and adults9,21,24, while a study in the elderly reported a significant association between SHS and elevated serum IL-6 levels25. An insignificant association between SHS exposure and serum TNF-α was reported by four studies, two in adolescents22,23 and two in adults9,24 and a positive association was reported by another study in adults24. Our study found that maternal exposure to SHS during pregnancy was significantly associated with elevated serum levels of TNF-α and IL-1β but not IL-6. There is little information on the relationship between SHS exposure and serum VCAM-1. Only one study, by Matsunaga et al., has reported an insignificant association between them in adolescents22 and a similar result was observed in our study. To the best of our knowledge, there has been no report on the effect of SHS exposure on serum MCP-1 levels. Nevertheless, two studies in aged persons25 and healthy adults26 reported that active smokers had higher serum MCP-1 concentrations than never smokers and Garliches et al. found that young healthy male smokers had slightly decreased serum MCP-1 levels27. However, there was no significant difference between the serum MCP-1 levels of pregnant women with and without SHS exposure in our study. Taken as a whole, the previous discrepant results on inflammatory markers may be explained by differences in the duration and extent of SHS exposure and the age, gender, biological status and ethnicity of the subjects in different studies22. Therefore, further studies are needed to clarify the effects of SHS exposure on inflammatory markers in pregnant women.

There is abundant evidence showing that maternal active smoking during pregnancy profoundly alters placental weight, morphology and function17,28,29,30. However, there is little research on how maternal exposure to SHS during pregnancy affects the placenta. A study by Rath et al. indicated that maternal exposure to SHS in pregnancy could produce similar ultra-structural changes as maternal active smoking30, while another study by Ramesh et al. observed no significant differences in placental surface area, volume and weight between pregnant women with and without SHS exposure31. However, our study found that pregnant women exposed to SHS had a lower placental weight than those not exposed to SHS. These discrepancies may due to differences in the duration and extent of maternal exposure to SHS during pregnancy and the ethnicity of subjects.

Although the association between LBW and inflammation has been explored, the results varied for the different kinds of inflammatory markers and with the period of pregnancy in which the specimens were collected. With regards to the association between maternal serum TNF-α level and LBW, three studies reported that pregnant women with LBW had significantly higher serum TNF-α levels before delivery than those with normal birth weight32,33,34. Similarly, our study showed that a high maternal serum TNF-α level before delivery significantly increased the risk of full-term LBW. A study by Amu et al. found significantly elevated serum IL-1β levels in women who delivered with IUGR35. Kalinderis et al. reported the same result in women with LBW and complications with pre-eclampsia36. Elfayomy et al. found that women with full-term IUGR had significantly higher serum IL-6 levels than women with babies appropriately grown for gestational age (AGA)31 and Steenwinkel et al. reported that maternal serum IL-6 levels during the first trimester were significantly associated with poor foetal growth in pregnant women with rheumatoid arthritis37. In line with the findings of two other studies32,34, we discovered a non-significant association between maternal serum IL-6 and full-term LBW. To date, there are no consistent reports on the association between maternal serum CRP level and LBW. For instance, Tjoa et al. reported that an elevated maternal serum CRP level during the first trimester of pregnancy significantly increased the risk of delivering a growth-restricted baby38. In contrast, maternal serum CRP level in the second trimester was not significantly associated with IUGR39 and a non-significant difference in maternal serum CRP before delivery was observed between pregnant women with IUGR and AGA40. Similarly, our study showed no significant differences between the maternal serum CRP levels of women with LBW and normal birth weight. There are limited reports on the associations between LBW and maternal serum levels of MCP-1 and VCAM-1. To the best of our knowledge, only two studies have found maternal serum MCP-1 levels to be lower in women with IUGR than control groups41,42 and one study found an insignificant difference between the maternal serum VCAM-1 levels of SGA cases and controls43. However, our study did not find significant associations between full-term LBW and maternal serum levels of MCP-1 and VCAM-1. To the best of our knowledge, there are no published studies on the relationship between maternal serum IL-1β and LBW. Interestingly, we found a significant positive association between them. We assumed that the discrepancies in the results of these studies might be caused by differences in the period of pregnancy in which samples were taken and the ethnicity of subjects.

The association between placental weight and birth weight is well established. Previous studies provide consistent evidence that placental weight is much lower in LBW cases than in control groups with normal birth weight14,15,16. Another study found that other placental gross indicators, such as the minor axis of the placenta surface, were sensitive to the mother’s nutritional state and foetal nutritional demands44. In accordance with these findings, our study found that lower placental weight was significantly associated with the risk of full-term LBW.

In line with previous findings7, our study also found that SHS exposure during pregnancy significantly increased the risk of full-term LBW after controlling for potential confounding factors. Our study indicated two potential pathways by which maternal SHS exposure during pregnancy might cause full-term LBW. First, maternal exposure to SHS increased maternal systemic IL-1β and TNF-α, which then triggered the secretion of IL-6, CRP and VCAM-1. Subsequently, both TNF-α andVCAM-1 caused a decrease in placental weight, which had a direct effect on foetal weight. Second, maternal SHS exposure induced maternal secretion of TNF-α, which could cross the placenta and directly increase the risk of full-term LBW. Similarly, Ouyang et al. found that placental weight mediated the effects of prenatal factors on foetal growth18 and several other studies have indicated that increased maternal systematic inflammation mediated the association of periodontal disease11, maternal sleep disturbances during pregnancy12 and pre-pregnancy BMI13 with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Taken together, these findings imply that maternal inflammation and its effect on the placenta may serve as mediators in the process by which maternal prenatal exposure to SHS and other factors affect foetal growth and lead to full-term LBW.

As a critical maternal inflammatory marker in our study, TNF-α is a pleiotropic pro-inflammatory cytokine, which may have direct effects on the placenta. Previous studies have suggested that an excessive level of TNF-α may damage the placenta by inhibiting the growth of the trophoblast, causing apoptosis of trophoblast cells, interfering with the development and invasion of placental spiral arteries and damaging the endothelium and decidual vasculature45,46. Elevated maternal serum levels of TNF-α were found in IUGR cases with placental insufficiency but not in normal pregnancy46,47, which could explain our finding that TNF-α indirectly affected full-term LBW by decreasing placental weight. In addition, a study found that TNF-α can transfer through the placenta and infiltrate the foetal circulation48. TNF-α may be involved in the metabolic regulation of glucose, lipids and insulin resistance by down-regulating insulin-stimulated glucose uptake and affecting the glucose transporter, the insulin receptor autophosphorylation and the insulin receptor substrate-1, all of which tend to reduce lipid accumulation within adipose tissue49,50. This may explain the other potential pathway through which TNF-α can cause full-term LBW without any decrease in placental weight in this study.

Our results revealed a noteworthy role of VCAM-1. As a marker of endothelial cell activation, VCAM-1 is a crucial adhesion molecule in both efficient placentation and adequate placental vasculature development51. A previous study found that low levels of VCAM-1 could be partly responsible for defects in trophoblastic cells, poor endovascular invasion and a lack of epithelial-endothelial transformation52, all of which contribute to the pathological basis of LBW. Utero-placental deficiency has also been attributed to decreased VCAM-1 expression in cases of foetal growth restriction53. Moreover, TNF-α and IL-1β can stimulate human endothelial cells to express VCAM-154,55. All of these findings may explain our finding that maternal VCAM-1 level was directly associated with maternal serum TNF-α, IL-6 and CRP levels and indirectly with IL-1β via TNF-α. Taken together, these results indicate that VCAM-1 may play a crucial mediation role in the associations between maternal serum inflammatory cytokines and placental functioning and indirectly affect full-term LBW by influencing placental weight.

We explain the biological mechanisms of maternal exposure to SHS during pregnancy resulting in full-term LBW as follows. First, some of the components (such as carbon monoxide, nicotine, cadmium, etc.) in SHS may cause a maternal inflammatory response. Then, some inflammatory cytokines (such as TNF-α, IL-1β and VCAM-1) may damage the placenta or affect placental development resulting in deficiencies in its size, structure and function; finally, the damaged or insufficiently developed placenta is unable to transfer sufficient nutrients and oxygen from the maternal body to the foetus, which may eventually lead to full-term LBW.

Several limitations should be addressed. First, all of the subjects were sampled from women and children’s hospitals in this study, which might have caused a selection bias that would limit the generalisability of our findings. Second, maternal SHS exposure was retrospectively assessed using a questionnaire that might have introduced information bias and confused the association between maternal SHS exposure during pregnancy and full-term LBW. Third, we only measured placental weight, while other physical parameters of the placenta, such as the placental width and length and the cord placement, may also predict outcomes. Fourth, inflammation is an active process involving the release of an extensive array of inflammatory markers, yet this study only included six markers. Therefore, further research should take a ‘systematic biology’ approach to explore how disturbances in inflammatory networks may lead to full-term LBW. Fifth, we only obtained maternal serum at one time point, near parturition, which limited our ability to define the temporal changes in these cytokine profiles and weakened the clinical application value when attempting to predict adverse pregnancy outcomes early in gestation. Parturition may also increase the level of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and thus the association between inflammatory markers and full-term LBW may be more complicated than our simplified explanation. Although we controlled for gestational age as a potential confounder in this study, an elaborately designed study with measurement at different gestational weeks would be better able to explain the association between inflammatory markers and full-term LBW. Sixth, despite the indirect effect explaining 48.4% of the total effect, the mediating effect of placental weight and maternal inflammatory markers on the associations between maternal SHS exposure during pregnancy and full-term LBW is only partial, rather than complete. Moreover, in contradiction with the previous finding that TNF-α may not cross the placenta56, our study found that TNF-α had a direct effect on full-term LBW without decreasing placental weight. Thus, other pathways, such as placental inflammation and vascular pathology, may lead to more substantial mediation of the effect of maternal SHS exposure during pregnancy on full-term LBW. Seventh, we estimated gestational age using the last menstrual period; however, as this measure may be inaccurate, more precise methods should be used to measure gestational age in future studies. Finally, we made the simplified assumption that the direction of the maternal-placenta-foetal effect was one way. As foetal growth can influence placental growth, this may also account for the partial mediation found in this study.

In summary, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the pathways through which maternal exposure to SHS during pregnancy causes full-term LBW via maternal inflammatory mediators and damage to the placenta. Our findings support the above hypothesis and thus extend our understanding of the mechanisms of full-term LBW and provide necessary insights for the development of novel, effective and targeted immunomodulatory therapies to improve pregnancy outcomes.

Methods

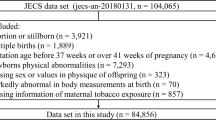

Participants

The study population consisted of 390 pregnant women who gave birth to full-term (≥37 weeks) infants at the Maternity and Child Health Care Hospitals of Shenzhen and Foshan in Guangdong, China, from September 2009 to March 2010. Birth weight was measured on an electronic balance scale immediately after birth. Mothers whose infants weighed less than 2500 grams were categorised as full-term LBW cases. When a full-term LBW case was enrolled, a control was randomly selected from the mothers with newborns with a normal birth weight (2,500–4,000 grams) and gestational age of ≥37 weeks who went into labour on an adjacent date (+/−3 days) in the same hospital. Overall, 195 LBW cases and 195 controls were recruited in this case-control study. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, China and it was carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines. All of the participants understood the study and gave their written informed consent.

Mothers who had an infectious disease in the last trimester were excluded from the study to avoid bias in the measures of inflammation due to their infectious status. Women with the following characteristics or behaviour were not included: 1) actively smoked cigarettes during pregnancy; 2) had one or more pre-existing chronic renal diseases, lung disease, diabetes, hypertension, hyperthyroidism or anaemia; 3) had an induced or accidental abortion; 4) had multiple births or newborns with birth defects; 5) had one or more obstetric complications, such as pre-eclampsia, antepartum haemorrhage, placenta previa etc.; and 6) placenta calcification.

Data collection

In the postnatal face-to-face interview, each selected mother was asked to complete a structured questionnaire on her social-demographic information, medical history, reproductive history, health behaviour and pre-pregnancy weight and height.

The medical records were reviewed to collect detailed gestational medical and obstetrical information including medication, last menstrual date, early ultrasound assessment, birth weight, infant gender, parity and placental weight.

Measurement and definition of maternal SHS exposure

The information about maternal exposure to SHS during pregnancy was collected at the postpartum interview, as reported previously57. Briefly, a set of questions were asked: ‘Have you ever smoked even one cigarette?’, ‘Were you ever exposed to passive smoking during pregnancy?’, ‘If yes, how many minutes per day, on average, were you exposed to passive smoke during each of the first, second and last trimesters?’. The average maternal exposure to SHS during pregnancy was calculated as the arithmetic mean of the number of minutes per day in the three trimesters of pregnancy. Maternal exposure to SHS during pregnancy was defined as an average maternal exposure time of more than 0 minutes per day.

Measurement of placental weight

The placenta, with membranes and large clots but with the cord trimmed, was weighed immediately after birth on an electronic balance scale in decagrams to the nearest 10 g. A lower placental weight was defined as below the median (500 g).

Measurement of inflammation

Maternal blood samples were collected within 12 hours after the eligible mothers were admitted to the hospital for parturition and they were not in active labour or membrane rupture. Two millilitres of maternal peripheral venous blood were collected in a serum separator tube and centrifuged at 3000 rounds/minute to obtain the serum. The serum specimens were immediately stored in a freezer at −80 °C until all of the samples were collected. Freezing and thawing cycles were avoided during the sample collection process.

The maternal serum levels of six inflammatory markers, MCP-1 (monocyte chemotactic protein-1), IL-6 (interleukin-6), TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor-α), IL-1β (interleukin-1β), CRP (C-reactive protein) and VCAM-1 (soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1), were measured using flow cytometric (bead-based) multiplex assays with the Human Basic Kit Flow Cytomix (a basic kit used in combination with BMS simplex kits to perform the quantitative detection of soluble human analytes by Flow Cytometry, Code: BMS8420FF, eBioscience, USA) and Flow Cytomix (CRP: BMS8288FF; VCAM-1: BMS8232/2FF; MCP-1: BMS8281FF; IL-1β: BMS8224FF; IL-6: BMS8213FF; TNF-α: BMS8223FF, eBioscience, USA) on a BD FACS Calibur instrument (BD Biosciences, USA), in strict accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Data were obtained using Cell Quest software (BD Bioscience) and calculated using the Flow Cytomix program (eBioscience, USA).

Potential confounders

According to the literature58,59,60,61, we defined maternal age, education level, family income, pre-pregnant BMI, parity, newborn gender and gestational age as potential confounders in this study.

Data analysis

Means and standard deviations (SD) were used to describe continuous variables. Levels of serum inflammatory markers were logarithmically transformed and described as geometric means with 95 per cent confidence intervals (95% CIs). Proportions were used to describe the distributions of categorical variables.

First, Chi-square tests were used to examine the associations between full-term LBW and maternal social-demographic and clinical characteristics and Student’s t tests or Satterthwaite t-tests were performed to test the differences in maternal age, gestational age, placental weight and log-transformed maternal serum levels of inflammatory markers between the full-term LBW group and the normal control group.

Second, logistic regression analysis was performed to test the associations between full-term LBW and maternal exposure to SHS during pregnancy, lower placental weight and maternal serum levels of inflammatory markers, with adjustment for potential confounders. Partial correlation analyses were conducted to examine the correlations between any two of the maternal inflammatory markers while controlling for the potential confounders.

Third, SEM was conducted to explore the potential pathways of maternal inflammation and lower placental weight in the association between maternal exposure to SHS during pregnancy and full-term LBW, on the basis of the fit between our data and the hypothesised pathways54,55. The model fit was evaluated by the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) ≤ 0.10, goodness of fit index (GFI), incremental fit index (IFI) and comparative fit index (CFI) ≥ 0.9062,63.

All P values were two-sided and statistical significance was set at P = 0.05. The structural equation model was calculated using AMOS version 17 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, Illinois, USA) and all of the other statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Niu, Z. et al. Potential pathways by which maternal second-hand smoke exposure during pregnancy causes full-term low birth weight. Sci. Rep. 6, 24987; doi: 10.1038/srep24987 (2016).

References

Valero De Bernabé, J. et al. Risk factors for low birth weight: a review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 116, 3–15 (2004).

Divon, M. Y., Haglund, B., Nisell, H., Otterblad, P. O. & Westgren, M. Fetal and neonatal mortality in the post term pregnancy: the impact of gestational age and fetal growth restriction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 178, 726–31 (1998).

Wiles, N. J. et al. Fetal growth and childhood behavioral problems: results from the ALSPAC cohort. Am J Epidemiol 163, 829–37 (2006).

van Deutekom, A. W., Chinapaw, M. J., Vrijkotte, T. G. & Gemke, R. J. Study protocol: the relation of birth weight and infant growth trajectories with physical fitness, physical activity and sedentary behavior at 8–9 years of age - the ABCD study. BMC Pediatr 13, 102. 10.1186/1471-2431-13-102 (2013).

Leunissen, R. W. J. et al. Timing and tempo of first-year rapid growth in relation to cardiovascular and metabolic risk profile in early adulthood. JAMA 301, 2234–2242 (2009).

Wadsworth, M. et al. Early growth and type 2 diabetes: evidence from the 1946 British birth cohort. Diabetologia 48, 2505–2510 (2005).

Salmasi, G., Grady, R., Jones, J. & McDonald, S. D. Knowledge Synthesis Group. Environmental tobacco smoke exposure and perinatal outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 89, 423–41 (2010).

Clark, J. D. et al. Inflammatory markers and secondhand tobacco smoke exposure among US workers. Am J Ind Med 51, 626–32 (2008).

Chiu, Y. H. et al. Secondhand smoke exposure and inflammatory markers in nonsmokers in the trucking industry. Environ Health Perspect 119, 1294–300 (2011).

Mullins, E. et al. Changes in the maternal cytokine profile in pregnancies complicated by fetal growth restriction. Am J Reprod Immunol 68, 1–7 (2012).

Cetin, I. et al. Pathogenic mechanisms linking periodontal diseases with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Reprod Sci 19, 633–41 (2012).

Okun, M. L., Roberts, J. M., Marsland, A. L. & Hall, M. How Disturbed sleep may be a risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes A hypothesis. Obstet Gynecol Surv 64, 273–80 (2009).

Friis, C. M. et al. The interleukins IL-6 and IL-1Ra: a mediating role in the associations between BMI and birth weight? J Dev Orig Heal Dis 1, 310–8 (2010).

Salafia, C. M., Charles, A. K. & Maas, E. M. Placenta and fetal growth restriction. Clin Obstet Gynecol 49, 236–56 (2006).

Vedmedovska, N. et al. Placental pathology in fetal growth restriction. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 155, 36–40 (2011).

Roland, M. C. et al. Fetal growth versus birthweight: the role of placenta versus other determinants. Plos One 7, e39324 (2012).

Zdravkovic, T. et al. The adverse effects of maternal smoking on the human placenta: a review. Placenta ; 26 Suppl A, S81–6 (2005).

Ouyang, F. et al. Placental weight mediates the effects of prenatal factors on fetal growth: the extent differs by preterm status. Obesity 21, 609–20 (2013).

Holcberg, G. et al. Increased production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha TNF-alpha by IUGR human placentae. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 94, 69–72 (2001).

Zhang, J., Fang, S. C., Mittleman, M. A., Christiani, D. C. & Cavallari, J. M. Secondhand tobacco smoke exposure and heart rate variability and inflammation among non-smoking construction workers: a repeated measures study. Environ Health 12, 83 (2013).

Bonetti, P. O. et al. Effect of brief secondhand smoke exposure on endothelial function and circulating markers of inflammation. Atherosclerosis 215, 218–22 (2011).

Matsunaga, Y. et al. The relationship between cotinine concentrations and inflammatory markers among highly secondhand smoke exposed non-smoking adolescents. Cytokine 66, 17–22 (2014).

Wilson, K. M. et al. Secondhand smoke exposure and serum cytokine levels in healthy children. Cytokine 60, 34–7 (2012).

Flouris, A. D., Metsios, G. S., Jamurtas, A. Z. & Koutedakis, Y. Sexual dimorphism in the acute effects of secondhand smoke on thyroid hormone secretion, inflammatory markers and vascular function. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 294, E456–62 (2008).

Levitzky, Y. S. et al. Relation of smoking status to a panel of inflammatory markers: the Framingham offspring. Atherosclerosis 201, 217–24 (2008).

Kuschner, W. G., D’Alessandro, A., Wong, H. & Blanc, P. D. Dose-dependent cigarette smoking-related inflammatory responses in healthy adults. Eur Respir J 9, 1989–94 (1996).

Garlichs, C. D. et al. CD40/CD154 system and pro-inflammatory cytokines in young healthy male smokers without additional risk factors for atherosclerosis. Inflamm Res 58, 306–11 (2009).

Ashfaq, M., Janjua, M. Z. & Nawaz, M. Effects of maternal smoking on placentalmorphology. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 15, 12–5 (2003).

Jauniaux, E. & Burton, G. J. Morphological and biological effects of maternal exposure to tobacco smoke on the feto-placental unit. Early Hum Dev 83, 699–706 (2007).

Rath, G., Dhuria, R., Salhan, S. & Jain, A. K. Morphology and morphometric analysis of stromal capillaries in full term human placental villi of smoking mothers: anelectron microscopic study. Clin Ter 162, 301–5 (2011).

Ramesh, K. N. et al. Maternal passive smoking and its effect on maternal, neonatal and placentalparameters. Med J Malays 60, 305e10 (2005).

Bartha, J. L., Romero-Carmona, R. & Comino-Delgado, R. Inflammatory cytokines in intrauterine growth retardation. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 82, 1099–102 (2003).

Elfayomy, A. K. et al. Serum levels of adrenomedullin and inflammatory cytokines in women with term idiopathic intrauterine growth restriction. J Obstet Gynaecol 33, 135–9 (2013).

Raghupathy, R., Al-Azemi, M. & Azizieh, F. Intrauterine growth restriction: cytokine profiles of trophoblast antigen-stimulated maternal lymphocytes. Clin Dev Immunol 2012, 734865 (2012).

Amu, S. et al. Cytokines in the placenta of Pakistani newborns with and without intrauterine growth retardation. Pediatr Res 59, 254–8 (2006).

Kalinderis, M. et al. Elevated serum levels of interleukin-6, interleukin-1beta and human chorionic gonadotropin in pre-eclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol 66, 468–75 (2011).

de Steenwinkel, F. D. et al. Circulating maternal cytokines influence fetal growth in pregnant women with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 72, 1995–2001 (2013).

Tjoa, M. L. et al. Elevated C-reactive protein levels during first trimester of pregnancy are indicative of preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction. J Reprod Immunol 59, 29–37 (2003).

Haedersdal, S. et al. Inflammatory markers in the second trimester prior to clinical onset of preeclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction and spontaneous preterm birth. Inflammation 36, 907–13 (2013).

Boutsikou, T. et al. Circulating levels of inflammatory markers in intrauterine growth restriction. Mediators Inflamm 2010, 790605 (2010).

Briana, D. D. et al. Perinatal plasma monocyte chemotactic protein-1 concentrations in intrauterine growth restriction. Mediators Inflamm 2007, 65032 (2007).

Georgiou, H. M. et al. Association between maternal serum cytokine profiles at 7-10 weeks’ gestation and birthweight in small for gestational age infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol 204, 415.e1–e12 (2011).

Bretelle, F. et al. Maternal endothelial soluble cell adhesion molecules with isolated small for gestational age fetuses: comparison with pre-eclampsia. BJOG 108, 1277–82 (2001).

Alwasel, S. H. et al. The breadth of the placental surface but not the length is associated with body size at birth. Placenta 33, 619–22 (2012).

Haider S. & Knofler M. Human tumour necrosis factor: physiological and pathological roles in placenta and endometrium. Placenta 30, 111–123 (2009).

Raghupathy, R., Al-Azemi, M. & Azizieh, F. Intrauterine growth restriction: cytokine profiles of trophoblast antigen-stimulated maternal lymphocytes. Clin Dev Immunol 2012, 734865. 10.1155/2012/734865 (2012).

Bartha, J. L., Romero-Carmona, R. & Comino-Delgado, R. Inflammatory cytokines in intrauterine growth retardation. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 82, 1099–102 (2003).

Zaretsky, M. V., Alexander, J. M., Byrd, M. & Bawdon, R. F. Transfer of inflammatory cytokines across the placenta. Obstet Gynecol 103, 546–50 (2004).

Nieto-Vazquez, I. et al. Insulin resistance associated to obesity: the link TNF-alpha. Arch Physiol Biochem 114, 183–194 (2008).

Coppack, S. W. Pro-inflammatory cytokines and adipose tissue. P Nutr Soc 60, 349–56 (2001).

Luppi, P. & Deloia, J. A. Monocytes of preeclamptic women spontaneously synthesize pro-inflammatory cytokines. Clin Immunol 118, 268–75 (2006).

Zhou, Y., Damsky, C. H. & Fisher, S. J. Preeclampsia is associated with failure of human cytotrophoblasts to minic a vascular adhesion phenotype. One cause of defective endovascular invasion in the syndrome? J Clin Invest 99, 2152–64 (1997).

Rajashekhar, G. et al. Expression and secretion of the vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 in human placenta and its decrease in fetal growth restriction. J Soc Gynecol Investig 10, 352–60 (2003).

Medzhitov, R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature 24, 428–35 (2008).

Jabbour, H. N., Sales, K. J., Catalano, R. D. & Norman, J. E. Inflammatory pathways in female reproductive health and disease. Reproduction 138, 903–19 (2009).

Aaltonen, R., Heikkinen, T., Hakala, K., Laine, K. & Alanen, A. Transfer of proinflammatory cytokines across term placenta. Obstet Gynecol 106, 802–807 (2005).

Xie, C. et al. Comparsion of secondhand smoke exposure measures during pregnancy in the development of a clinical prediction model for small-for-gestational-age among non-smoking Chinese pregnant women. Tob Control 24, e179–e187 (2014).

van den Berg, G. et al. Suboptimal maternal vitamin D status and low education level as determinants of small-for-gestational-age birth weight. Eur J Nutr 52, 273–279 (2013).

Shah, P. S. Parity and low birth weight and preterm birth: a systematic review and meta‐analyses. Acta Obstet Gyn Scan 89, 862–875 (2010).

Shah, P. S., Jamie Z. & Samana A. Maternal marital status and birth outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Matern Child Health J 15, 1097–1109 (2011).

Blumenshine, P. et al. Socioeconomic disparities in adverse birth outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 39, 263–272 (2010).

Kline, R. B. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford, New York (1998).

Bentler, P. M. On the fit of models to covariances and methodology to the Bulletin. Psychol B 112, 400 (1992).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 30872164 & 81172758). The authors acknowledge the support of the Shenzhen Women and Children’s Hospital and Foshan Women and Children’s Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.N. contributed to hypothesis generation, study design, data collection, data analysis, result interpretation and drafting manuscript. W.-Q.C. contributed to hypothesis generation, study design, data analysis plan, result interpretation and revising the manuscript. C.X., X.W., F.T., S.Y. and D.J. contributed to field survey, blood sample collection and laboratory tests.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Niu, Z., Xie, C., Wen, X. et al. Potential pathways by which maternal second-hand smoke exposure during pregnancy causes full-term low birth weight. Sci Rep 6, 24987 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep24987

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep24987

This article is cited by

-

Low birthweight of children is positively associated with mother’s prenatal tobacco smoke exposure in Shanghai: a cross-sectional study

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2020)

-

Early exposure to thirdhand cigarette smoke affects body mass and the development of immunity in mice

Scientific Reports (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.