Abstract

Several epidemiological studies have investigated the association between dietary flavonoid intake and digestive tract cancers risk; however, the results remain inconclusive. The aim of our study was to evaluate this association. PubMed and the Web of Knowledge were searched for relevant publications from inception to October 2015. The risk ratio (RR) or odds ratio (OR) with the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for the highest versus the lowest categories of flavonoid intake were pooled using a fixed-effects model. A total of 15 articles reporting 23 studies were selected for the meta-analysis. In a comparison of the highest versus the lowest categories of dietary flavonoid intake, we found no significant association between flavonoid intake and oesophageal cancer (OR = 0.91, 95% CI = 0.75–1.10; I2 = 0.0%), colorectal cancer (OR = 1.02, 95% CI = 0.92–1.14, I2 = 36.2%) or gastric cancer (OR = 0.88; 95% CI = 0.74–1.04, I2 = 63.6%). The subgroup analysis indicated an association between higher flavonoid intake and a decreased risk of gastric cancer in the European population (OR = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.62–0.97). In conclusion, the results of this meta-analysis do not strongly support an association between dietary flavonoid intake and oesophageal or colorectal cancer. Furthermore, the subgroup analysis suggested an association between higher dietary flavonoid intake and decreased gastric cancer risk in European population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Digestive tract cancers are very common malignant tumous worldwide and are an important cause of cancer-related death1,2. Globocan 2012 showed that the standardised incidences of colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, and oesophageal cancer placed them in the 4th, 6th, and 10th positions among all tumours, respectively1.

Epidemiological evidence suggests that diet may play an important role in the aetiology of digestive tract cancer risk3,4,5,6. Diets high in fruits and vegetables are inversely associated with the incidence of digestive tract cancers5,6,7,8. Flavonoids are a group of bioactive polyphenols that are abundant in plant-based foods, such as fruits and vegetables3. The biological effects of flavonoids for cancer prevention include the regulation of cell signaling and the cell cycle, antimutagenic and antiproliferative properties, free radical scavenging, and inhibition of angiogenesis9,10.

Several epidemiological studies have investigated the relationship between flavonoid intake and digestive tract cancer risk. However, these results are controversial. A systematic review of the literature to date might be helpful for confirming any such association. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to determine, in a meta-analysis, whether an association exists between dietary flavonoid intake and cancers of the digestive tract.

Materials and Methods

Search strategy

The electronic databases PubMed and Web of Knowledge (through October 2015) were searched to identify eligible studies. The following keywords were used: “flavonoids” OR “flavanones”, OR “flavones”, “anthocyanidins” OR “catechin” combined with “oesophagus cancer” OR “oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma”, “colorectal cancer” OR “colon cancer” OR “rectal cancer”; “gastric cancer” OR “stomach cancer”. Besides, we checked the reference list of all articles of interest to identify additional eligible publications.

Study selection

The articles selected met the following criteria: (1) the studies were designed as cohort or case–control studies; (2) the exposure of interest was total dietary flavonoid intake; (3) the outcome of interest was the incidence of digestive tract cancers, including oesophageal cancer, gastric cancer, and colorectal cancer; (4) the odds ratios (ORs) or relative risk (RR) estimates with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were reported or could be calculated. If data were duplicated in more than one study, the one with the largest number of cases or the longest follow-up period was included in the meta-analysis.

Data extraction

Two authors (Yacong Bo and Jinfeng Sun) independently extracted the following information from each study: the first author’s last name, year of publication, country, study design (case-control or cohort), patient characteristics (including sample size, gender, and mean age), the reported ORs (RRs) with 95% CIs for the highest versus the lowest categories of flavonoid intake, and variables adjusted in the analysis of each study. The ORs (RRs) that reflected the greatest degree of control for potential confounders were adopted in this meta-analysis. Any disagreements were resolved by a third investigator.

Statistical analysis

The pooled ORs with 95% CIs (highest compared to the lowest category of flavonoid intake) were computed from the adjusted ORs and RRs to measure the association between dietary flavonoid intake and the risk of digestive tract cancers.

The extent of heterogeneity across studies was determined using a chi-square test and an I2 test; if P < 0.05 and/or I2 > 50%, indicating significant heterogeneity, a random-effect model was selected. Otherwise, a fixed-effect model was applied11. Meta-regression and subgroup analyses were performed to explore the possible source of heterogeneity, such as geographic region, experimental design, sample size and publication year12,13. Subgroup analyses were also performed to evaluate the potential effect of the modification of variables, including the study design, geographic region, cancer subtype, and dose. Begg’s funnel plots and Egger’s linear regression test were performed to assess the publication bias. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant14,15.

All analyses were conducted using STATA software (version 12.0; StatCorp, College Station, TX, USA) and a value of P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Literature search and study characteristics

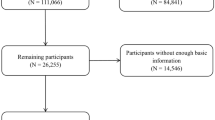

The electronic search of PUBMED and web of knowledge identified a total of 1595 potentially relevant articles. Fifty-one articles were reviewed in full after reviewing the title and abstract. Among them, 7 articles were reviews, 27 articles reported sub-class flavonoids, and 2 articles reported flavonoid supplements. As a result, 15 articles reporting 23 studies, encompassing 312,734 digestive tract cancer cases and 1,142,276 controls were selected for the meta-analysis16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. The detailed steps of our literature search are shown in Fig. 1, and the main characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1.

Flavonoid intake and overall digestive tract cancer risk

We pooled the study-specific ORs using a fixed-effect model. No significant associations were detected between the highest compared with the lowest category of flavonoid intake and digestive tract cancers (overall OR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.89–1.05, I2 = 36.1%) (Fig. 2).

Flavonoid intake and oesophageal cancer risk

Seven studies examined the association between flavonoid intake and oesophageal cancer risk. The pooled OR of oesophageal cancer for the highest versus lowest categories of flavonoid intake was 0.91 (95% CI = 0.75–1.10, I2 = 0.0%), suggesting that flavonoid intake was not significantly associated with the risk of oesophageal cancer (Fig. 2).

As shown in Table 2, a subgroup analysis was conducted by geographic location, study design, and histological type. However, non-significant associations of dietary flavonoid intake with oesophageal cancer were detected among all strata for the between-study subgroup analyses.

Flavonoid intake and colorectal cancer risk

A total of eight studies assessed the association between dietary flavonoid intake and colorectal cancer risk. The pooled OR of colorectal cancer risk for the highest versus the lowest categories of flavonoid intake was 1.02 (95% CI = 0.92–1.14, I2 = 36.2%), indicating that flavonoid intake was not significantly associated with colorectal cancer risk.

The subgroup analysis indicated that dietary flavonoid intake has no significant effect on colorectal cancer risk in the US or European population. For colorectal cancer subtypes, no significant association was found between flavonoid intake and colon cancer (pooled OR = 0.92, 95% CI = 0.80–1.05) or rectal cancer (pooled OR = 0.90, 95% CI = 0.75–1.08), as shown in Table 2.

Flavonoid intake and gastric cancer risk

Six studies investigated flavonoid intake and gastric cancer risk. As shown in Fig. 2, the meta-analyses demonstrated no significant association between gastric cancer risk and flavonoid intake (OR = 0.88; 95% CI = 0.74–1.04, I2 = 63.6%) for a comparison of the highest to the lowest category of intake.

In the subgroup analysis, we found that flavonoid intake was significantly associated with gastric cancer risk in Europe (pooled OR = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.62–0.97), but not in the United States or Asia (Table 2). With respect to study design, we did not find that flavonoid intake was statistically associated with gastric cancer in either the cohort (pooled OR = 0.86, 95% CI = 0.67–1.09) or case-control studies (pooled OR = 0.90, 95% CI = 0.72–1.13).

Heterogeneity analysis

For most of the outcomes of digestive tract cancer, the I2 values of heterogeneity were lower than 50%. Only the levels of heterogeneity for gastric cancer were intermediate (I2 = 63.6%). To explore the sources of heterogeneity, we performed subgroup analyses with stratification by geographic location and study design. We found that flavonoid intake was significantly associated with gastric cancer risk in Europeans (pooled OR = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.62–0.97) but not in Americans or Asians. Therefore, geographic location may partially account for the appreciable heterogeneity. Meta-regression showed that study design, geographic location, source of controls, and publication year had no significant impact on heterogeneity. Moreover, the leave-one-out analysis showed that the key contributor to heterogeneity was the study conducted by Zamora-Ros16. After excluding this study, the heterogeneity was reduced to I2 = 23.4%, and the summary OR for oesophageal cancer was 1.304 (95% CI = 0.807–1.325), which was similar to the main finding.

Publication bias

Egger’s test showed no significant publication bias in this meta-analysis (t = −1.46, P = 0.158 for digestive tract cancers, t = −0.49, P = 0.644 for oesophageal cancer, t = −0.06, P = 0.951 for colorectal cancer, and t = −1.56, P = 0.170 for gastric cancer), and the funnel plots are shown in Fig. 3.

Funnel plot for publication bias of flavonoids intake and digestive tract cancers risk (A) Funnel plot of publication bias for all digestive tract cancers, (B) Funnel plot of publication bias for esophageal cancer, (C) Funnel plot for publication bias of colorectal cancer, (D) Funnel plot for publication bias of gastric cancer.

Discussion

The present meta-analysis first evaluated the association between dietary flavonoid intake and the risk of digestive tract cancers based on the highest versus the lowest categories. We found no significant association between the highest dietary flavonoid intake and oesophageal cancer, colorectal cancer, or gastric cancer. However, studies conducted in European populations indicated an association between higher flavonoid intake and a decreased risk of gastric cancer.

Previous epidemiological studies have suggested that flavonoid intake has no significant effect on breast cancer (RR = 0.98, 95% CI = 0.86–1.12)31 or colorectal neoplasms (RR = 1.03, 95% CI = 0.88–1.20 )32. The meta-analysis also suggested a significant association between the highest category of flavonoid intake and a reduced risk of lung cancer (RR = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.63–0.92)33. The association between dietary flavonoid intake and the risk of digestive cancers identified in our meta-analysis adds new information regarding the relationship between flavonoid intake and cancer risk.

The lack of a strong association between flavonoid intake and oesophageal or colorectal cancer is particularly surprising because numerous in vitro and animal studies have demonstrated an inverse association between flavonoid and oesophageal or colorectal cancer34,35,36,37. However, many flavonoids present in foods cannot be absorbed in their native form, including esters, glycosides, and polymers38. It has been demonstrated that the amount of flavonoids that are bioavailable is only a small proportion of the ingested amount, ranging from 0.2–0.9% for tea catechins to 20% for quercetin and isoflavones39,40. In in vitro and animal studies, the intake of flavonoids is much higher than that in humans, and it remains unclear whether the beneficial antiproliferative and antioxidative effects observed during vitro studies are also present in humans41. Other studies have also suggested that flavonoids have weaker actions in vivo than in vitro42.

In the subgroup analysis by geographic location, we found an inverse association between flavonoid intake and gastric cancer in Europe but not in America or Asia. The reasons for this may include the complexity due to the presence of flavonoids from various food sources, the occurrence of a large amount of flavonoids in nature, and the diversity of dietary culture43. The main dietary sources of flavonoids are fruits, vegetables, tea, and red wine44. However, the flavonoids in vegetables and fruits depend on the type of cultivation, crop variety and location, as well as the specific morphological part of the plant45. Moreover, we could not exclude cultural differences in the storage and preparation of foods, particularly vegetables, which may also lead to this result.

Medium heterogeneity was detected for the association between flavonoid intake and gastric cancer. A meta-regression was used to explore the sources of heterogeneity, which showed that the study design, geographic location, source of controls, and publication year had no significant impact on heterogeneity. Then, we performed subgroup analyses by study design and geographic location and, found that flavonoid intake was significantly associated with gastric cancer risk in Europe, but not in America or Asia, suggesting that the intermediate heterogeneity is partially explained by geographic location. Moreover, the leave-one-out analysis showed that the key contributor to heterogeneity was the study conducted by Zamora-Ros16. After excluding this study, the summary estimate was not materially altered, but the I2 of heterogeneity was reduced from 63.6% to 23.4%.

The role of flavonoids in gastric carcinogenesis has been attributed to several mechanisms. Flavonoids have anticarcinogenic effects by way of their antioxidant properties, which are attributed to their ability to modulate antioxidant pathways46. Moreover, flavonoids can regulate cell proliferation and apoptosis, modulate phase I and II metabolic enzymes, and affect inflammatory pathways47. Another possible explanation for the protective effects of flavonoids m may be their potential anti-Helicobacter pylori effect48, including direct bactericidal activity, the neutralisation of VacA, the reduction of urease secretion, and interference with Toll-like receptor 4 signaling49, which is unique to gastric cancer. Therefore, high dietary flavonoids intakes can possibly reduce the risk of gastric but not esophageal or colorectal cancer.

Several potential limitations of our meta-analyses should be acknowledged. The relatively small number of studies analysed makes it difficult to evaluate heterogeneity. Furthermore, we only compared the risk of cancer for those in the highest category of flavonoid intake with that of those in the lowest category of flavonoid intake, and the definition of these intake categories varied between studies. In addition, only published studies were included in the meta-analysis, which may have biased the results.

Conclusion

In summary, this meta-analysis provides little evidence of an association between the highest category of dietary flavonoid intake and the risk of oesophageal cancer or colorectal cancer. However, a subgroup analysis demonstrated that dietary flavonoids could reduce the risk of gastric cancer in the European population although not the U.S. or Asian populations.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Bo, Y. et al. Dietary flavonoid intake and the risk of digestive tract cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 6, 24836; doi: 10.1038/srep24836 (2016).

References

Torre, L. A. et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 65, 87–108 (2015).

Glade, M. J. Food, nutrition, and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. American Institute for Cancer Research/World Cancer Research Fund, American Institute for Cancer Research, 1997. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif) 15, 523–526 (1999).

Woo, H. D. & Kim, J. Dietary Flavonoid Intake and Smoking-Related Cancer Risk: A Meta-Analysis. Plos One 8, e75604 (2013).

Vial, M., Grande, L. & Pera, M. Epidemiology of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, gastric cardia, and upper gastric third. Recent Results Cancer Res 182, 1–17 (2010).

Li, B. et al. Intake of vegetables and fruit and risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur J Nutr 53, 1511–1521 (2014).

Pericleous, M., Mandair, D. & Caplin, M. E. Diet and supplements and their impact on colorectal cancer. J Gastrointest Oncol 4, 409–423 (2013).

Luo, W.-P. et al. High consumption of vegetable and fruit colour groups is inversely associated with the risk of colorectal cancer: a case-control study. Br J Nutr 113, 1129–1138 (2015).

Vuong, Q. V. et al. Fruit-derived phenolic compounds and pancreatic cancer: Perspectives from Australian native fruits. J Ethnopharmacol 152, 227–242 (2014).

Neuhouser, M. L. Dietary flavonoids and cancer risk: Evidence from human population studies. Nutr Cancer 50, 1–7 (2004).

Moon, Y. J., Wang, X. D. & Morris, M. E. Dietary flavonoids: Effects on xenobiotic and carcinogen metabolism. Toxicol In vitro 20, 187–210 (2006).

Higgins, J. P. T., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J. & Altman, D. G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327, 557–560 (2003).

Higgins, J. P. T. & Thompson, S. G. Controlling the risk of spurious findings from meta-regression. Stat Med 23, 1663–1682 (2004).

Li, P. et al. Association between dietary antioxidant vitamins intake/blood level and risk of gastric cancer. Int J Cancer 135, 1444–1453 (2014).

Begg, C. B. & Mazumdar, M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 50, 1088–1101 (1994).

Egger, M., Davey Smith, G., Schneider, M. & Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315, 629–634 (1997).

Zamora-Ros, R. et al. Dietary flavonoid and lignan intake and gastric adenocarcinoma risk in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study. Am J Clin Nutr 96, 1398–1408 (2012).

Wang, L. et al. Dietary intake of selected flavonols, flavones, and flavonoid-rich foods and risk of cancer in middle-aged and older women. Am J Clin Nutr 89, 905–912 (2009).

Woo, H. D. et al. Dietary Flavonoids and Gastric Cancer Risk in a Korean Population. Nutrients 6, 4961–4973 (2014).

Hirvonen, T., Virtamo, J., Korhonen, P., Albanes, D. & Pietinen, P. Flavonol and flavone intake and the risk of cancer in male smokers (Finland). Cancer Causes Control 12, 789–796 (2001).

Simons, C. C. J. M. et al. Dietary flavonol, flavone and catechin intake and risk of colorectal cancer in the Netherlands Cohort Study. Int J Cancer 125, 2945–2952 (2009).

Mursu, J. et al. Intake of flavonoids and risk of cancer in Finnish men: The Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study. Int J Cancer 123, 660–663 (2008).

Lin, J. et al. Flavonoid intake and colorectal cancer risk in men and women. Am J Epidemiol 164, 644–651 (2006).

Zamora-Ros, R. et al. Association between habitual dietary flavonoid and lignan intake and colorectal cancer in a Spanish case-control study (the Bellvitge Colorectal Cancer Study). Cancer Causes Control 24, 549–557 (2013).

Rossi, M. et al. Flavonoids and colorectal cancer in Italy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 15, 1555–1558 (2006).

Rossi, M. et al. Flavonoids and risk of squamous cell esophageal cancer. Int J Cancer 120, 1560–1564 (2007).

Vermeulen, E. et al. Dietary Flavonoid Intake and Esophageal Cancer Risk in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition Cohort. Am J Epidemiol 178, 570–581 (2013).

Bobe, G. et al. Flavonoid consumption and esophageal cancer among black and white men in the United States. Int J Cancer 125, 1147–1154 (2009).

Petrick, J. L. et al. Dietary intake of flavonoids and oesophageal and gastric cancer: incidence and survival in the United States of America (USA). Br J Cancer 112, 1291–1300 (2015).

Garcia-Closas, R., Gonzalez, C. A., Agudo, A. & Riboli, E. Intake of specific carotenoids and flavonoids and the risk of gastric cancer in Spain. Cancer causes control 10, 71–75 (1999).

Knekt, P. et al. Flavonoid intake and risk of chronic diseases. Am J Clin Nutr 76, 560–568 (2002).

Hui, C. et al. Flavonoids, flavonoid subclasses and breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. PloS one 8, e54318–e54318 (2013).

Jin, H., Leng, Q. & Li, C. Dietary flavonoid for preventing colorectal neoplasms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 8, CD009350–CD009350 (2012).

Tang, N.-P., Zhou, B., Wang, B., Yu, R.-B. & Ma, J. Flavonoids Intake and Risk of Lung Cancer: A Meta-analysis. Jpn J Clin Oncol 39, 352–359 (2009).

He, Y., Jin, H., Gong, W., Zhang, C. & Zhou, A. Effect of onion flavonoids on colorectal cancer with hyperlipidemia: an in vivo study. Onco Targets Ther 7, 101–110 (2014).

Du, W. J. et al. Antitumor Activity of Total Flavonoids from Daphne genkwa in Colorectal Cancer. Phytother Res 30, 323–330 (2015).

Wang, L. S. et al. Anthocyanins in black raspberries prevent esophageal tumors in rats. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2, 84–93 (2009).

Wang, L. et al. The flavonoid Baohuoside-I inhibits cell growth and downregulates survivin and cyclin D1 expression in esophageal carcinoma via beta-catenin-dependent signaling. Oncol Rep 26, 1149–1156 (2011).

Manach, C., Scalbert, A., Morand, C., Remesy, C. & Jimenez, L. Polyphenols: food sources and bioavailability. Am J Clin Nutr 79, 727–747 (2004).

Hollman, P. C., de Vries, J. H., van Leeuwen, S. D., Mengelers, M. J. & Katan, M. B. Absorption of dietary quercetin glycosides and quercetin in healthy ileostomy volunteers. Am J Clin Nutr 62, 1276–1282 (1995).

Lee, M. J. et al. Analysis of plasma and urinary tea polyphenols in human subjects. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 4, 393–399 (1995).

Yang, C. S., Landau, J. M., Huang, M. T. & Newmark, H. L. Inhibition of carcinogenesis by dietary polyphenolic compounds. Annu Rev Nutr 21, 381–406 (2001).

Tan, B.-J., Liu, Y., Chang, K.-L., Lim, B. K. W. & Chiu, G. N. C. Perorally active nanomicellar formulation of quercetin in the treatment of lung cancer. Int J Nanomedicine 7, 651–661 (2012).

Yao, L. H. et al. Flavonoids in food and their health benefits. Plant Foods Hum Nut 59, 113–122 (2004).

Zamora-Ros, R. et al. Estimation of Dietary Sources and Flavonoid Intake in a Spanish Adult Population (EPIC-Spain). J Am Diet Assoc 110, 390–398 (2010).

Kozlowska, A. & Szostak-Wegierek, D. Flavonoids--food sources and health benefits. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig 65, 79–85 (2014).

Hollman PC, C. A. et al. The biological relevance of direct antioxidant effects of polyphenols for cardiovascular health in humans is not established. J Nutr 141, 989S–1009S (2011).

Pierini, R., Gee, J. M., Belshaw, N. J. & Johnson, I. T. Flavonoids and intestinal cancers. Br J Nutr 99, ES53–ES59 (2008).

Fukai, T. et al. Anti-Helicobacter pylori flavonoids from licorice extract. Life Sci 71, 1449–1463 (2002).

Cushnie, T. P. T. & Lamb, A. J. Recent advances in understanding the antibacterial properties of flavonoids. Int J Antimicrob Agents 38, 99–107 (2011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.L. and L.Y. designed the study. Y.B. and J.S. assessed the studies for inclusion, extracted the data, and assessed the validity. Y.B. and M.W. conducted the meta-analyses and tabulated the data. Y.B. and J.D. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Q.L. and L.Y. provided critical review of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Bo, Y., Sun, J., Wang, M. et al. Dietary flavonoid intake and the risk of digestive tract cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 6, 24836 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep24836

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep24836

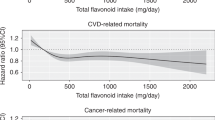

This article is cited by

-

Habitual dietary intake of flavonoids and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: Golestan cohort study

Nutrition Journal (2020)

-

Dietary intake of total polyphenol and polyphenol classes and the risk of colorectal cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort

European Journal of Epidemiology (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.