Abstract

Insects are extremely successful animals whose odor perception is very prominent due to their sophisticated olfactory system. The main chemosensory organ, antennae play a critical role in detecting odor in ambient environment before initiating appropriate behavioral responses. The antennal chemosensory receptor genes families have been suggested to be involved in olfactory signal transduction pathway as a sensory neuron response. The Macrocentrus cingulum is deployed successfully as a biological control agent for corn pest insects from the Lepidopteran genus Ostrinia. In this research, we assembled antennal transcriptomes of M. cingulum by using next generation sequencing to identify the major chemosensory receptors gene families. In total, 112 olfactory receptors candidates (79 odorant receptors, 20 gustatory receptors, and 13 ionotropic receptors) have been identified from the male and female antennal transcriptome. The sequences of all of these transcripts were confirmed by RT-PCR, and direct DNA sequencing. Expression profiles of gustatory receptors in olfactory and non-olfactory tissues were measured by RT-qPCR. The sex-specific and sex-biased chemoreceptors expression patterns suggested that they may have important functions in sense detection which behaviorally relevant to odor molecules. This reported result provides a comprehensive resource of the foundation in semiochemicals driven behaviors at molecular level in polyembryonic endoparasitoid.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Olfaction is a finely tuned sense of smell. It plays critical role to detect chemicals cues in their environment, essential for insects in foraging, host-seeking, mating choice, oviposition site locating by females, warning and defense1,2,3. Accurate detection of volatile compounds in the surrounding environment is required for their survival.

In almost all of the insects, repertoires of several ones to several hundred highly divergent odorant receptors (ORs) are responsible for detecting a myriad of volatile chemical signals in the environment4. Insect chemoreceptors consist of three major gene families appear to form binding sites for odorant molecules at the membrane surface of olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs)5,6,7, the odorant receptors (ORs)8,9,10,11, gustatory receptors (GRs)12,13,14,15,16,17, and recently discovered variant ionotropic glutamate receptors (IRs)5,18,19, whose environmental chemical signals are converted into electrical signals interpreted by the nervous system – starting with the binding of odor molecules to odorant receptors neuron (ORN) dendrites to the brain20,21.

The ORs of both insects and vertebrates have seven transmembrane domains (TMDs), but insects ORs do not belong to the canonical G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), to which have a reversed membrane topology (intracellular N-terminus)8,22. The first ORs genes, identified in the genomic analysis of Drosophila melanogaster encoded seven transmembrane domains that were largely expressed in morphological and functional types of olfactory sensilla, especially trichoid and basiconic sensilla8,10,11. Multiple ORs have now been identified in species from at least four insect orders, including Diptera, Lepidoptera, Hymenoptera and Coleoptera23,24,25,26,27. These ORs display a high divergence (only 20–40% identities) in their sequences among or within species28. Insect ORs are frequently co-expressed with a nonconventional OR previously referred to as OR83b in D. melanogaster, OR2 in Bombyx mori, and OR7 in mosquitoes, but these nonconventional OR have been universally named as olfactory receptor co-receptor (Orco)29. The ORs detect a variety of odor compounds30,31, including pheromones32 and microbe derivative or plant volatile compounds33. Some of ORs are characterized by their response specificity33, whereas others appear more broadly tuned at high stimulus concentrations30.

GRs are mostly expressed in gustatory receptor neurons in taste organs involving in contact chemoreception34. Insect GRs and ORs are distantly related members of the same superfamily9. The GRs are more conserved in sequence and structure than ORs35,36, probably due to a comparatively smaller search space on associated cues. These GRs typically detect sugars, bitter compounds, and contact pheromones37.

IRs were discovered in D. melanogaster by bioinformatic analyses as another class of receptors involved in chemoreception5. Apparently, IRs are related to ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGlurs), which are involved in synaptic signal transduction in both vertebrates and invertebrates20,34. Unlike ORs, IRs have been identified throughout protostomia (including arthropods, mollusks, annelids and nematodes) and, thus, constitute a far more ancient group of receptors than the ORs19. Due to the IRs have atypical binding domains that are more conserved than ORs, it is possible to identify several paralogous lineages among insects20. IR-induced responses appear to be conferred by assemblies of variable subunits in a heteromeric receptor, as up to five different IRs can be co-expressed in a single OSN5. A functional complex formed by two or more subunits of IRs, including odor-specific receptors and one or two broadly expressed receptors (in D. melanogaster, IR25a and IR8a) that function as co-receptors38. IRs in insects are divided into major two types: the “antennal IRs” are conserved across insect orders with chemosensory function, and the “divergent IRs” is species-specific and assigned a tentative role in taste19.

Except the receptor genes, several multigene protein families have also been discovered to play critical roles in olfaction, including: odorant binding proteins (OBPs)39,40; chemosensory proteins (CSPs)41,42; sensory neuron membrane proteins (SNMPs)43,44; and odorant degrading enzymes (ODEs)45. Several extensive studies have been described the characteristics and potential roles of these genes in insect olfaction5,37,42,43,45,46.

Identification of receptors gene families has largely been possible in insects of which genomic data are available due to their abundance and sequence diversity17,47. With the recent advances in RNA-Seq and computational technologies has been used widely such type identifications in non-model organisms. Usages these technologies, a wide range of insects olfactory genes have identified and reported of which no sequenced genome is available20,34,47,48,49,50,51. Within the Macrocentrus cingulum Brischke (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), very limited number of olfactory genes including co-receptors52 have been identified. However, only one candidate gene from OBP family (McinOBP 1) has been identified with function study1, while others candidate genes remaining to be identified.

The identification of olfactory receptors genes families- ORs, GRs and IRs in polyembryonic endoparasitoid wasps will provide information regarding their chemical communication and it’s crucial for genetic manipulation of their sensitivity to chemical cues using in biocontrol systems. This research investigated the antennal chemosensory gene families of the M. cingulum by antennal transcriptomes from next-generation sequencing. M. cingulum is a polyembryonic endoparasitoid of the Asian corn borer, Ostrinia furnacalis (Guenée) (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) and the European corn borer, O. nubilalis (Hübner)53,54 and is distributed across Europe and throughout Asia, including Japan, Korea and China55. M. cingulum has evolved an efficient olfaction system like other parasitoids use herbivore induced plant volatiles (HIPVs) and green leaf volatiles (GLVs) from infested plants by host insect as chemical cues. Female M. cingulum use host larval frass in stalk tunnels as host-searching cues56. Our previous study with this wasp, only 9 ORs has been identified (accession number KC887063-71), consequently, additional receptors genes to be investigated to permits a better understanding of the molecular basis of polyembryonic endoparasitoid olfaction. Identification of the chemosensory genes can ultimately lead to comprehensive understanding of how to recognize and locate host for oviposition in this wasp. Our present research investigated the antennal chemosensory gene families of the M. cingulum from antennal transcriptomes by next-generation sequencing.

Results

Sequencing and assembly

Through the Illumina HiSeq 2500 RNA-Seq strategy, the male and female M. cingulum antennal transcriptomes generated of 2,73,13,634 and 2,64,69,263 clean reads respectively, and assembled to 57,179 transcripts and 41,254 unigenes with 1,571 bp and 982 bp mean length respectively (Table 1). The sample GC content was 41.22% for female and 39.98% for male, and the average quality value was ≥30 for female 90.49% and 90.41% for male (Table 2). The N50 was 3,787 bp for transcripts and 2,383 for unigenes. Approximately 5,353 unigenes were longer than 2 kb. The total length of the assembled transcriptome was about 40.5 Mbp. The clean reads of the M. cingulum antennal transcriptome were deposited in the NCBI_SRA database, under the accession number of SRR2968845.

Functional annotation

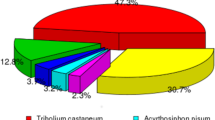

The functional annotations of the unigenes were performed mainly with deposited in diverse protein datasets listed in methods section. In total of 41,254 unigenes, 10,977 (26.6%) unigenes in the Nr database, 4,283 (10.38%) unigenes Nt data base, 5,248 (12.72%) in the KO database, 8,737 (21.17%) unigenes in the SwissPort database, 10,741 (26.03%) unigenes in the Pfam database, 10,781 (26.13%) unigenes in the GO database, 7,110 (17.23%) in the KOG database, 2,197 (5.32%) in the all database and 14,113 (34.21%) unigenes in the at least one database were annotated (Table 3). Using Nr database annotation, 7,114 (64.8%) unigenes matched to known proteins. Among the 10,977 annotated unigenes, 5,313 (48.4%) had a strong match (e-value smaller than1e−45) whereas 1,240 (11.3%) showed poor homology with e-value between 1e−15 and1e−5 (Fig. 1A). From the Nr annotation, 39.8% unigenes showed 60–80% and 37.8% unigenes showed 80–95% similarity with known proteins (Fig. 1B). Nr database queries revealed that 65.5% sequences closely matched to hymenopteran sequence (Microplitis demolitor 51.7%, Nasonia vitripennis 4.0%, Apis dorsata 2.8%, Cerapachys biroi 2.7 and Megachile rotundata 4.3%) (Fig. 1C).

From Gene Ontology (GO) annotation the M. cingulum antennal transcriptome unigenes (10,781 of 41,254 unignes) were associated with GO terms which cover three domains: biological process, cellular component and molecular function (Fig. 2, and supplementary Fig. S1). In the terms of biological process; cellular, metabolic and single organism processes represented most of genes. In the molecular function terms, mostly associated with binding activity (e.g. nucleotide binding, odorant binding, ion binding), and catalytic activity (e.g. hydrolase and oxidoreductase activity). In the cellular category, cell, and cell part were the most abundant (Fig. 2).

GO analysis corresponding to 10,781 contig sequences in M. cingulum, as predicted for their involvement in (A) molecular function (level 2 GO categorization) and (B) biological process (level 2). For results presented as detailed bar diagrams, see supplementary Fig. S1.

In total 5,994 unigene sequences are annotated to 256 pathways using with Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway database to identify the metabolic pathways which are populated by these unigenes. The “metabolic pathway” populated with highest number of unigenes (1,578, 26.33%) followed by Cellular Processes pathways (1,422, 23.72%); and “Organismal Systems pathways” (1,400, 23.35%) (Fig. 3). This annotation information helps to conduct further research on metabolic function and pathways, and biological behaviors of M. cingulum genes.

Identification of olfactory receptor gene families

Odorant receptors

Bioinformatic analysis of the M. cingulum antennal transcriptomes identified 109 sequences including previously described ORs McinOR1-9 and McinOrco52 that encode candidate OR genes. The transcript name, length, best BLASTx hit, identity, and male or female specificity was summarized in Table 4. While the length of 20 other amino acid sequences ≤100 are provided as supplementary material in Table S2. A full-length McinOrco gene coding 479 amino acids was easily identified because it contained the intact open reading frame and seven transmembrane domains, which are typical characteristics of insect ORs. The majority of partial length transcripts possess overlapping regions with low amino acid sequence identity, indicating that they represented separate individual proteins. However, the possibility that the remaining non-overlapping transcripts represented fragments of individual proteins cannot be excluded; therefore, the total number of McinORs reported could be reduced by 20, based on sequence alignments and subsequent fragment location (i.e. C-terminus, internal, or N-terminus). We eventually analyzed 89 OR (including our previous identified ORs/Orco) sequences in our phylogenetic analysis.

With exception of Orco, the predicted ORs shared quite low identity probably due to the high variance among OR gene family. Only three of 79 ORs (McinOR12, McinOR15, and McinOR42) showed more than 50% identity with known ORs in NCBI database (Table 4). The phylogenetic analysis also showed that ORs were extremely divergent between species but formed monophyletic group within same species (Fig. 4). However the highly conserved Orco shared 95–99% amino acid sequence identity and clustered in same branch with orthologous relation among three species (Fig. 4). All of the other McinORs were distributed in different branches of the phylogenetic tree. Eight species specific subgroups were identified consisting of different numbers of McinORs. The highest 14 McinORs (OR11, 24, 36, 52, 55, 56, 67, 68, 74, 78, 80, 81, 85, and 86) and the lowest three McinORs (OR30, 60 and 84) and another three McinORs (OR1, 7 and 59) clustered within the species specific subgroup. Others McinOR are clustered with N. vitripennis or M. mediator ORs.

Gustatory receptors

We identified 20 transcripts encoding candidate GRs in the M. cingulum antennal transcriptome (Table 5). Most of candidate McinGRs were partial transcripts (only six represents full length protein), encoding overlapping but distinct sequences. This shows individual genes though it’s being fragment of protein sequence. A phylogeny was built with these 20 McinGRs, N. vitripennis, A. mellifera and D. melanogaster (Fig. 5). Based on the phylogenetic analysis, McinGRs were also observed to group with their presumed Drosophila orthologues, which have been shown to have roles in carbon dioxide detection (GR21a and GR63a)57,58 and are members of the candidate sugar GR64 receptor subfamily (GR64e)59 or bitter (DmelGR93a)60 Drosophila receptors (Fig. 5).

Ionotropic receptors

We identified 13 transcripts for putative ionotropic receptors in M. cingulum antennal transcriptome according to their similarity to IR sequence of other insects. Comparative analysis revealed that one candidate IR (MmedIR8a) was deemed as IR8a homolog to its high identity (71%). IR25a and IR76b shared 57% and 46% identity with MmedIR25a.1 and MmedIR76b, respectively. It has been reported that, the above three genes (IR8a, IR25a and IR76b) are thought to play function as IR co-receptors5,38. In the phylogenetic tree of IRs, all McinIR candidates clustered with their ionotropic receptor orthologs into separate sub-clades (Fig. 6). Because of the relative high conservation of IRs, all the splits of McinIRs were strongly supported by high support values. The candidate IR unigenes were named according to their similarity to known IRs. The information, including unigene reference, length, and best blastx hit of all IRs were listed in Table 6.

Tissue and sex specific expression profile of candidate M. cingulum chemosensory receptors

We performed reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) analyses in different tissues of adult males and females to explore the expression patterns of M. cingulum OR, GR and IR genes. Most of OR genes were expressed in male and female antennae, the crucial chemosensory organs, suggesting a functional role of these genes in olfaction (Fig. 7). The candidate OR31, 59, 62, 64, and 65 showed a male antenna specific expression, while only one OR25 was expressed only in female antennae. The remaining ORs were expressed in both sexes, by differential expressions in male or female among tissues. Five of them, OR11, 14, 54, 55 and 81 were most highly (>200 M. pixel) expressed in both male and female antennae (Fig. 7). Twenty-one ORs (OR18, 19, 22, 35, 38, 41, 43, 46, 48, 49, 50, 52, 53, 57, 60, 63, 67, 69, 70, 79, and 82) were clearly expressed higher in male compared to female while only two (OR27 and 40) expressed higher level in female than male. GRs and IRs showed a ubiquitous expression pattern except the McinGR12, 14 and 15 which was present predominantly in the male legs; McinIR64a prominent in male and female antennae but IR8a and 25a only in male antennae. McinIR76b dominantly expressed in male leg (Fig. 8).

Comparison of expression profile of olfactory receptor (OR) genes in male and female adult antennae and body as revealed by RT-PCR. In each box, the relative abundance value in (M. pixel) of each receptor gene is indicated. Color scales were established using the conditional formatting option in Excel (color scale shown inside the figure).

Comparison of expression profile of gustatory receptor (GR) and ionotropic receptors (IR) genes in male and female adult antennae and head with mouth parts, leg and body as revealed by RT-PCR. In each box, the relative abundance value in (M. pixel) of each receptor gene is indicated. Color scales were established using the conditional formatting option in Excel (color scale shown inside the figure).

The quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was used to investigate the gustatory receptor transcript abundances in the male antennae, head with mouth parts, legs, body and female antennae, head with mouth parts, legs and body tissues. By comparing expression levels McinGR10, 13, 14, 17, 18 and 19 genes were expressed at similar level in all tested tissues except 14, 18, and 19 in body of both sexes (Fig. 9). McinGR1, 3, 4, 15 and 20 were prominently expressed only male antennae and legs where as McinGR6, 8 and 11 in male antennae, legs and female legs but 16 dominantly expressed only in male legs (Fig. 9). McinGR2, 7, and 9 were highly expressed in female antenna than male. McinGR5 were highly expressed in male antenna than female.

Discussion

This is the first comprehensive analysis of a polyembryonic endoparasitoid antennal transcriptome for the purpose to identify the major chemosensory receptor gene families (ORs, GRs and IRs) for olfaction. The identified gene families represent a valuable genomic resource of molecular basis in M. cingulum due to potential target genes for manipulating parasitoid wasp’s behavior and improving biocontrol techniques.

The GO annotation demonstrated that predicted three categorize functions of M. cingulum transcripts overall similar as those obtained from previous reports34,51,61,62. Identified individual transcripts of olfactory gene families were also comparable with other Dipteran, Coleopteran, Hymenopteran and Lepidopteran species from those of which the antennal transcriptome has been reported20,34,61,63,64,65,66. The comparison of these published data sets suggested a certain level of conservation in gene expression patterns in antennae.

From the M. cingulum antennal transcriptome, a total of 109 OR genes were identified including with our previous studies. The total number of identified ORs in M. cingulum greater than the M. mediator (68 ORs)51 but less than in A. mellifera (170 ORs) or N. vitripennis (301 ORs)67,68. Identified OR genes were only from the antennal transcriptome, ORs from other tissues thus might be difficult to identify in our study. However, the differences of identified OR gene number may result from sequencing methods and depth, and/or sample preparation. The large number of ORs identified in M. cingulum also could result from species difference; so, further research is required for confirmation.

Insect ORs mainly expressed in the antennae69. Present research revealed several ORs have sex specific expression, while others showed ubiquitous expression pattern but their expression level higher in antennae. The differential expression patterns of McinORs have been supported by previous study51,70,71,72. The male antennae specific ORs (31, 59, 62, 64, 65, and 66) or male biased (18, 19, 22, 45, 38, 41, 43, 46, 48, 49, 50, 52, 53, 57, 60, 63, 67, 69, 70, 79, and 82) expression profiles may play crucial roles in the detection of sex pheromone or male specific behaviors. The female specific OR25 or female biased OR27, 40, and 58, may suggest that the female specific behaviors i.e. finding host for ovipositions or others. Additionally, ORs expressed in other organ of wasp may have physiological functions, for example a Orco expressed in the testes of A. gambiae was considered to involve in spermatozoa activation71.

The GR family of insect chemoreceptors includes receptors for sugars and bitter compounds, as well as cuticular hydrocarbons and odorants such as CO2. Antennal GRs of insects used for tasting purpose as well as for olfaction detects73. However, there are no reports of polyembryonic endoparasitoid wasp GRs in antenna. So far we know, it is the first report of GR family in this wasp chemoreceptors, although some studies described the distribution of some gustatory sensilla in wasp antennae51,74. We identified 20 putative GR-encoding transcripts from the M. cingulum antennal transcriptomes. The identified GRs also included potential carbon dioxide receptors, which suggested that M. cingulum might use CO2 detection as a cue for host selection, like in B. mori, T. castaneum and mosquitoes21,75. Orthologue GR64f clusters with sugar receptor of GR1 subfamily in Hymenoptera suggested a function of sugar detection. In addition, identified McinGRs were differentially expressed in sensory and non-sensory organs. However, the recent studies showed a wide range of non-gustatory sensory functions of insect GRs76, that indicated GRs probably have far more divergent functions in antennae.

Generally in insects, IRs are more conserved compared to ORs and GRs19, which can be categorized as divergent species-specific IRs and conserved antennal IRs5. The antennal IR subfamily only constituted a portion of IRs, while others belong to the divergent IRs subfamily, showed species-specific expansions that are particularly large in Diptera19. In D. melanogaster, there are 66 IRs, and 15 were antennal IRs77. In this study, 13 IR candidates including two co-receptors, (IR8a and IR25a) were found in antennal transcriptome. Limited number of IR genes identified in hymenoptera (only 6 in M. mediator, 10 in A. melifera and N. vitripennis) compared to diptera (66 in D. melanogaster)19. However, our identified IR genes close to the number of A. melifera and N. vitripennis but higher than the M. mediator. Sequence alignments showed that the putative McinIR8a and McinIR25a had high similarity with the MmedIR8a and MmedIR25a respectively. These two mostly expressed in female antennae than in male wasp, which probably play a significant roles in host recognition for oviposition51. However, the ubiquitous expression feature of McinIRs revealed that these genes may have other physiological functions in non-olfactory organs.

The M. cingulum transcriptome data indicated that the chemosensory gene repertoire was largely similar between the male and female, only differences in the relative levels of expression of individual ORs (Fig. 7). Therefore, while male and female antennae likely perceive similar odor stimuli, their sensitivities, and hence the odour significance to the male and female, may differ. Female M. cingulum uses host larval frass in combined with different volatile cues for host-searching. The herbivore induced plant volatiles (HIPVs) and green leaf volatiles (GLVs) are consider to be used by female wasps from infested plants by host insect as chemical cues78,79. The female specific or biased ORs in antennae may play important role in recognition of host volatiles, which can provide a key starting to manipulate and developed OR in wasp for finding host and used as a biological tools for pest control.

Conclusion

This study reports the first antennal transcriptome analysis in polyembryonic endoparasitoid M. cingulum. The genes reported here provide valuable insight into the molecular mechanisms of olfaction of this wasp. Ultimately, a large number of ORs, GRs and IRs in M. cingulum are identified, however the additional molecular and functional experiments are required to confirm the expression and roles of these genes. Our results provide a foundational knowledge to explore and understand the chemosensory receptor gene families of this wasp. It is promising to conduct transcriptomic analysis via next generation RNA-Seq for non-model organisms especially for polyembryonic parasitoid.

Methods

Insects

M. cingulum were collected from O. furnacalis larvae, which lived on infested corn plants in Langfang Experimental Station of Institute of Plant Protection, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, China. The parasitoids emerged as mature larvae from the host larvae and pupated inside the silken cocoon. Adult parasitoid wasps were fed with 20% honey solution. A laboratory colony was established and maintained at 25 °C with a 16 hr light: 8 hr dark photoperiod on host larvae of O. furnacalis that were reared on an artificial diet followed published procedures80.

Total RNA extraction

Antennae were cut from 1–2 days old male and female wasps following snap freezing in liquid nitrogen. The collection of head with mouth parts, legs, thoraxes, and abdomen (wingless) collected from same aged wasps were used for the RT-PCR validation of gene sequences. All the tissues were immediately stored at −80 °C for further processes. Total RNA was extracted from the antennae or other tissues using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) as per manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA integrity was verified by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and quantity was assessed with a Nanodrop ND-2000 spectrophotometer (Nano- Drop products, Wilmington, DE, USA). The integrity of the RNA was checked by the Agilent 2100 (Agilent Technologies Inc., CA, USA) before transcriptome sequencing.

Antennal transcriptome generations

Synthesis of cDNA and Illumina library generation was completed at Novogene Co., Ltd. Beijing, China, using Illumina HiSeq2500 sequencing. The FastQC tool was used to obtain read statistics, assess read quality, and to remove the low quality data. The high-quality reads were obtained by removing adaptor sequences, empty reads low-quality sequences (reads with unknown “N” >10% sequences), and the reads with more than 50% Q ≤ 20 base on the raw reads. All the analysis based on the clean reads. The the transcriptome data was combined and de novo assembled using Trinity81,82. Trinity RNA-Seq is highly capable of overcoming quality and polymorphism issues due to bubble popping algorithms in each of the three modules, Inchworm, Chrysalis and Butterfly. In order to get the comprehensive information of the genes, we annotated the genes based on Nr, Nt, Pfam, KOG/COG, Swiss-prot, KEGG, GO databases. Open reading frames were predicted using ESTScan 3.0 project. Gene expression levels were estimated by RSEM software83, and differential expression analysis of two groups was performed using the DESeq R package (1.10.1)84. P-value was adjusted using q-value85 and q-value < 0.005 and log2 (fold_change) >1 was set as the threshold for significantly differential expression.

Gene identification and annotation

For sequence homology assessment of both male and female M. cingulum antennal transcriptomes, gene ontology (GO) annotation was performed using Blast2Go via searches against the NCBI non-redundant protein database (using BLASTp with a 1e−10 threshold)86,87. GO annotated genes or transcripts were described into three domains: to molecular function, biological process, and cellular component, allowing for meta-analyses of gene populations61,88. Identification of putative chemosensory genes families by custom data base nucleotide Blast profile searches using known sequences as queries. M. cingulum chemosensory genes were in turn used as queries to identify additional genes (tBLASTx and BLASTp). Repetitions were completed until no new ones were identified. Identification of candidate genes was verified by additional BLAST searches using the M. cingulum contigs as queries against the NCBI non-redundant protein database (BLASTx). Protein domains (e.g. transmembrane domains, signal peptides, secondary structures, etc.) were predicted by queries against InterPro using the InterProScan Geneious software plugin running a batch analysis (e.g. HMMPanther, SignalPHMM, Gene3D, HMMPfam, TMHMM, HMMSmart, Superfamily, etc.)89. Membrane topology was assessed with Phobius90. In addition, we used KEGG ontology (KO) enrichment analyses to further understand their biological functions. Sequences were classified based on sequence similarity, domain structure predictions, and phylogenetic analysis.

Phylogenetic analysis

Amino acid sequences were aligned using MAFFT91 and BioEdit Sequence Alignment Editor 7.1.3.092 for further edit. Phylogenetic relationship was deduced by the maximum likelihood method using MEGA593 with the GAMMA model for rate heterogeneity and the WAG model for substitution matrix. In addition, the rapid hill-climbing search algorithm (–f d) was used. Model optimization precision in log likelihood units for final optimization of tree topology (–e) was set at 0.0001. The tree image subsequently viewed and graphically edited in Fig Tree v1.4.0 (http://tree.bio.ed. ac.uk/software/figtree/)94. Phylogenetic trees were based on Hymenopteran data sets. The OR data set contained 89 amino acid sequences from M. cingulum, together with N. vitripennis67 M. mediator51 and A. mellifera68. The GR data set contained 20 amino acid sequences from M. cingulum, together with sequences from N. vitripennis, A. mellifera and D. melanogaster67,68,95. The IR data set contained 13 M. cingulum amino acid sequences with M. mediator51, N. vitripennis, A. mellifera and D. melanogaster67,68,95 IR sequences.

RT-PCR analysis

To explore the expression of the ORs identified from the antennal transcriptome and compare the differential expression patterns between the sexes, RT-PCR was conducted with cDNAs prepared from the male antenna, female antenna, male and female body (including head, leg, thoraxes, abdomen) for OR genes and male and female antennae, head with maxillary palp, leg and body for GR and IR genes. Independent triplicate individual samples of total RNA were isolated from the above mentioned tissues and corresponding cDNAs were synthesized using the TranScript® one-step gDNA removal and cDNA synthesis supermix (TRANSGENE Biotech, Beijing, China) following the kit manual. β-actin was used as reference gene (accession number- EU585777.1) and it was used to select the cDNA templates on the PCR equipment. Primers were designed manually or by Primer 5 (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/primer5/), which was listed in supplementary material (Table S1). Individual PCR reactions were repeated three times; controls consisted of no template PCRs. The PCR conditions consisted of an initial 3-min step at 94 °C, 30 cycles of 94 °C for 30-sec, 56, 57 or 59 °C (depending on primers) for 30-sec and 72 °C for 3-min and finally 10-min step at 72 °C. Products were analyzed on a 1% agarose gel and visualized after staining with ethidium bromide. The images were recorded digitally by Dolphin-DOC (Wealtec Corp.) using 1141101 CCD-Camera, 12 V ac/dc and stored on computer. The brightness of each bands were measured from digital images by using Adobe Photoshop version CS3.

Quantitative real-time PCR measurement

Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was conducted to detect the relative expression levels of McinGRs in adult male and female different tissues of M. cingulum. The RNA/cDNA preparation of each tissue was performed in triplicate. The gene specific primer was designed using Primer express 5.0 and listed in Supplementary Material: Table S3. The housekeeping genes β-actin (accession number EU585777) was used in qPCR equipment as a reference gene. The gene specific primer and β-actin were used to measure the Ct values of the cDNA templates to ensure the Ct values were between 22 and 25. qPCR experiments were performed using 96 well plates (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA), ABI Prism 7500 Fast Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) and Brilliant II SYBR Green qPCR master mix (Takara). qPCR was conducted in 20 μL reactions containing 50x SYBR Premix Ex Taq 10 μL, primer (10 mM) 0.4 × 2 μL, ROX reference dye II 0.4 μL (50×), sample cDNA 1 μL, sterilized ultra-pure grade H2O 7.8 μL. Cycling conditions were: 95 °C for 30 sec, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 05 sec and 60 °C for 30 sec. Afterwards, the PCR products were heated to 95 °C for 15 sec, cooled to 60 °C for 1 min and heated to 95 °C for 15 sec to measure the dissociation curves. No-template and no-reverse transcriptase controls were included in each experiment. To check reproducibility, each test sample was done in triplicate technical replicates and three biological replicates. Relative quantification was performed by using the comparative 2−ΔΔCT method96. All data were normalized to endogenous β-actin levels from the same tissue samples and the relative fold change in different tissues was calculated with the transcript level of the abdomen as calibrator. Thus, the relative fold change in different tissues was assessed by comparing the expression level of each GR in other tissues to that in the abdomen.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Ahmed, T. et al. Gene set of chemosensory receptors in the polyembryonic endoparasitoid Macrocentrus cingulum. Sci. Rep. 6, 24078; doi: 10.1038/srep24078 (2016).

References

Ahmed, T., Zhang, T., Wang, Z., He, K. & Bai, S. Three amino acid residues bind corn odorants to McinOBP1 in the polyembryonic endoparasitoid of Macrocentrus cingulum Brischke. Plos ONE 9, e93501, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093501 (2014).

Sato, K. & Touhara, K. Insect olfaction: receptors, signal transduction, and behavior. Results Probl. Cell. Differ. 47, 121–138 (2009).

Hildebrand, J. G. & Shepherd, G. M. Mechanisms of olfactory discrimination:converging evidence for common principles across phyla. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 20, 595–631, doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.20.1.595 (1997).

Su, C.-Y., Menuz, K. & Carlson, J. R. Olfactory perception: receptors, cells, and circuits. Cell 139, 45–59 (2009).

Benton, R., Vannice, K. S., Gomez-Diaz, C. & Vosshall, L. B. Variant ionotropic glutamate receptors as chemosensory receptors in Drosophila . Cell 136, 149–162 (2009).

Touhara, K. & Vosshall, L. B. Sensing odorants and pheromones with chemosensory receptors. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 71, 307–332, doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163209 (2009).

Kaupp, U. Olfactory signalling in vertebrates and insects: differences and commonalities. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 188–200 (2010).

Clyne, P. J. et al. A novel family of divergent seven-transmembrane proteins: candidate odorant receptors in Drosophila . Neuron 22, 327–338 (1999).

Robertson, H., Warr, C. & Carlson, J. Molecular evolution of the insect chemoreceptor gene superfamily in Drosophila melanogaster . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 14537–14542 (2003).

Vosshall, L., Amrein, H., Morozov, P., Rzhetsky, A. & Axel, R. A spatial map of olfactory receptor expression in the Drosophila antenna. Cell 96, 725–736 (1999).

Gao, Q. & Chess, A. Identification of candidate Drosophila olfactory receptors from genomic DNA sequence. Genomics 60, 31–39 (1999).

Jones, W., Cayirlioglu, P., Kadow, I. & Vosshall, L. Two chemosensory receptors together mediate carbon dioxide detection in Drosophila . Nat. 445, 86–90 (2006).

Vosshall, L. & Stocker, R. Molecular architecture of smell and taste in Drosophila . Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 30, 505–533 (2007).

Dunipace, L., Meister, S., McNealy, C. & Amrein, H. Spatially restricted expression of candidate taste receptors in the Drosophila gustatory system. Curr. Biol. 11, 822–835 (2001).

Clyne, P. J., Warr, C. G. & Carlson, J. R. Candidate taste receptors in Drosophila . Sci. 287, 1830–1834, doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1830 (2000).

Scott, K. et al. A chemosensory gene family encoding candidate gustatory and olfactory receptors in Drosophila . Cell 104, 661–673 (2001).

Fox, A., Pitts, R., Robertson, H., Carlson, J. & Zwiebel, L. Candidate odorant receptors from the malaria vector mosquito Anopheles gambiae and evidence of down-regulation in response to blood feeding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 14693–14697 (2001).

Abuin, L. et al. Functional architecture of olfactory ionotropic glutamate receptors. Neuron 69, 44–60 (2011).

Croset, V. et al. Ancient protostome origin of chemosensory ionotropic glutamate receptors and the evolution of insect taste and olfaction. Plos Genet. 6, e1001064, doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001064 (2010).

Bengtsson, J. M. et al. Putative chemosensory receptors of the codling moth, Cydia pomonella identified by antennal transcriptome analysis. Plos ONE 7, e31620, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031620 (2012).

Robertson, H. & Kent, L. Evolution of the gene lineage encoding the carbon dioxide receptor in insects. J. Insect Sci. 9, 1–14 (2009).

Benton, R., Sachse, S., Michnick, S. W. & Vosshall, L. B. Atypical membrane topology and heteromeric function of Drosophila odorant receptors In vivo . Plos Biol. 4, e20, doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040020 (2006).

Hallem, E., Fox, A., Zwiebel, L. & Carlson, J. A mosquito odorant receptor tuned to a component of human sweat. Nat. 427, 212–213 (2004).

Krieger, J., Klink, O., Mohl, C., Raming, K. & Breer, H. A candidate olfactory receptor subtype highly conserved across different insect orders. J. Compar. Physiol. A 189, 519–526, doi: 10.1007/s00359-003-0427-x (2003).

Nakagawa, T., Sakurai, T., Nishioka, T. & Touhara, K. Insect sex-pheromone signals mediated by specific combinations of olfactory receptors. Sci. 307, 1638–1642 (2005).

Robertson, H. & Wanner, K. The chemoreceptor superfamily in the honey bee Apis mellifera: expansion of the odorant, but not gustatory, receptor family. Genome Res. 16, 1395–1403 (2006).

Wanner, K. et al. Female-biased expression of odourant receptor genes in the adult antennae of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Insect Mol. Biol. 16, 107–119 (2007).

Malpel, S., Merlin, C., François, M. C. & Jacquin-Joly, E. Molecular identification and characterization of two new Lepidoptera chemoreceptors belonging to the Drosophila melanogaster OR83b family. Insect Mol. Biol. 17, 587–596, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2008.00830.x (2008).

Vosshall, L. B. & Hansson, B. S. A unified nomenclature system for the insect olfactory coreceptor. Chem. Senses, doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjr022 (2011).

Hallem, E. A., Dahanukar, A. & Carlson, J. R. Insect odorant and taste receptors. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 51, 113–135, doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.51.051705.113646 (2006).

Carey, A., Wang, G., Su, C.-Y., Zwiebel, L. & Carlson, J. Odorant reception in the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae . Nat. 464, 66–71 (2010).

Sakurai, T. et al. Identification and functional characterization of a sex pheromone receptor in the silkmoth Bombyx mori . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 16653–16658 (2004).

Stensmyr, M. et al. A conserved dedicated olfactory circuit for detecting harmful microbes in Drosophila . Cell 151, 1345–1357 (2012).

Andersson, M. et al. Antennal transcriptome analysis of the chemosensory gene families in the tree killing bark beetles, Ips typographus and Dendroctonus ponderosae (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae). BMC Genomics 14, 1–16, doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-198 (2013).

McBride, C. & Arguello, J. Five Drosophila genomes reveal nonneutral evolution and the signature of host specialization in the chemoreceptor super familiy. Genetics 177, 1395–1416 (2007).

Gardiner, A., Barker, D., Butlin, R. K., Jordan, W. C. & Ritchie, M. G. Drosophila chemoreceptor gene evolution: selection, specialization and genome size. Mol. Ecol. 17, 1648–1657, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03713.x (2008).

Vosshall, L. & Stocker, R. Molecular architecture of smell and taste in Drosophila . Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 30, 505–533 (2007).

Abuin, L. et al. Functional architecture of olfactory ionotropic glutamate receptors. Neuron 69, 44–60 (2011).

Kaissling, K.-E. Olfactory perireceptor and receptor rvents in moths: a kinetic model. Chem. Senses 26, 125–150, doi: 10.1093/chemse/26.2.125 (2001).

Leal, W. et al. Kinetics and molecular properties of pheromone binding and release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 5386–5391 (2005).

Bohbot, J., Sobrio, F., Lucas, P. & Nagnan-Le Meillour, P. Functional characterization of a new class of odorant-binding proteins in the moth Mamestra brassicae . Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 253, 489–494 (1998).

Pelosi, P., Zhou, J., Ban, L. & Calvello, M. Soluble proteins in insect chemical communication. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 63, 1658–1676 (2006).

Benton, R., Vannice, K. S. & Vosshall, L. B. An essential role for a CD36-related receptor in pheromone detection in Drosophila . Nat. 450, 289–293 (2007).

Jin, X., Ha, T. & Smith, D. SNMP is a signaling component required for pheromone sensitivity in Drosophila . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 10996–11001 (2008).

Vogt, R. In Insect pheromone biochemistry and molecular biology: Biochemical diversity of odor detection: OBPs, ODEs and SNMPs (ed Blomquist G. Vogt R. ) 391–445 (San Diego Aca. 2003).

Martin, F., Boto, T., Gomez-Diaz, C. & Alcorta, E. Elements of olfactory reception in adult Drosophila melanogaster . Anatomical Rec. 296, 1477–1488, doi: 10.1002/ar.22747 (2013).

Zhou, X. et al. Phylogenetic and transcriptomic analysis of chemosensory receptors in a pair of divergent ant species reveals sex-specific signatures of odor coding. Plos Genet. 8, e1002930, doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002930 (2012).

Legeai, F. et al. An expressed sequence tag collection from the male antennae of the noctuid moth Spodoptera littoralis: a resource for olfactory and pheromone detection research. BMC Genomics 12, 86 (2011).

Yang, B., Ozaki, K., Ishikawa, Y. & Matsuo, T. Identification of candidate odorant receptors in asian corn borer Ostrinia furnacalis . Plos ONE 10, e0121261, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121261 (2015).

Xu, W., Papanicolaou, A., Liu, N. Y., Dong, S. L. & Anderson, A. Chemosensory receptor genes in the oriental tobacco budworm Helicoverpa assulta . Insect Mol. Biol. 24, 253–263, doi: 10.1111/imb.12153 (2015).

Wang, S. et al. Identification and expression analysis of putative chemosensory receptor genes in Microplitis mediator by antennal transcriptome screening. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 11, 737–751, doi: 10.7150/ijbs.11786 (2015).

Ahmed, T., Zhang, T., Wang, Z., He, K. & Bai, S. Olfactory co-receptor identification and expression pattern analysis in polyembryonic endoparasitoid Macrocentrus cingulum . J. Asia-Pacific Entomol. 18, 719–725 (2015).

Edwards, O. R. & Hopper, K. R. Using superparasitism by a stem borer parasitoid to infer a host refuge. Ecol. Entom. 24, 7–12, doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2311.1999.00165.x (1999).

Hu, J., Zhu, X.-X. & Fu, W.-J. Passive evasion of encapsulation in Macrocentrus cingulum Brischke (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), a polyembryonic parasitoid of Ostrinia furnacalis Guenée (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). J. Insect Physiol. 49, 367–375, doi: 10.1016/s0022-1910(03)00021-0 (2003).

Watanabe, C. Further revision of the genus Macrocentrus Curtis in Japan, with descriptions of two new species (Hymenoptera,Braconidae). Insecta Matsum. 30, 1–16 (1967).

Parker, H. L. Macrocentrus gifuensis Ashmead, a polyembrinic braconid parasite in the European corn borer. Tech. bull. 230, 1–61 (1931).

Zhou, D. R., Wang, Y. Y., Liu, B. L. & Ju, Z. L. Research on the reproduction of O. furnacalis in a large quantity: an artificial diet and its improvement Acta Phytophyl. Sin . 7, 113–122 (1980).

Grabherr, M. G. et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat . Biotech. 29, 644–652 d (2011).

Haas, B. J. et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat. Protocols 8, 1494–1512, doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.084 (2013).

Li, B. & Dewey, C. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 323 (2011).

Anders, S. & Huber, W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 11, R106 (2010).

Storey, J. D. & Tibshirani, R. Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 9440–9445, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530509100 (2003).

Conesa, A. et al. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics 21, 3674–3676, doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti610 (2005).

Götz, S. et al. High-throughput functional annotation and data mining with the Blast2GO. Nucl. Acids Res. 36, 3420–3435, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn176 (2008).

Grosse, W. E. et al. Antennal transcriptome of Manduca sexta . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 7449–7454, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017963108 (2011).

Ashburner, M. et al. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet 25, 25–29 (2000).

Quevillon, E. et al. InterProScan: protein domains identifier. Nucl. Acids Res. 33, W116–W120, doi: 10.1093/nar/gki442 (2005).

Käll, L., Krogh, A. & Sonnhammer, E. L. L. A combined transmembrane topology and signal peptide prediction method. J. Mol. Biol. 338, 1027–1036 (2004).

Katoh, K., Misawa, K., Kuma, K. i. & Miyata, T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucl. Acids Res. 30, 3059–3066, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf436 (2002).

Hall, T. A. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucl. Acids. Sym. Series 41, 95–98 (1999).

Tamura, K. et al. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2731–2739, doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121 (2011).

Rambaut, A. FigTree v1.4. 2007. http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk. (2015).

Robertson, H. M., Gadau, J. & Wanner, K. W. The insect chemoreceptor superfamily of the parasitoid jewel wasp Nasonia vitripennis . Insect Mol. Biol. 19, 121–136, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2009.00979.x (2010).

Robertson, H. M. & Wanner, K. W. The chemoreceptor superfamily in the honey bee, Apis mellifera: expansion of the odorant, but not gustatory, receptor family. Genome Res. 16, 1395–1403, doi: 10.1101/gr.5057506 (2006).

Chyb, S. Drosophila gustatory receptors: from gene identification to functional expression. J. Insect Physiol. 50, 469–477 (2004).

Kwon, J., Dahanukar, A., Weiss, L. & Carlson, J. The molecular basis of CO2 reception in Drosophila . PNAS 104, 3574–3578 (2007).

Jones, W. D., Cayirlioglu, P., Grunwald Kadow, I. & Vosshall, L. B. Two chemosensory receptors together mediate carbon dioxide detection in Drosophila . Nat. 445, 86–90 (2007).

Slone, J., Daniels, J. & Amrein, H. Sugar receptors in Drosophila . Curr. Biol. 17, 1809-1816,, doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.09.027.

Leitch, O., Papanicolaou, A., Lennard, C., Kirkbride, K. P. & Anderson, A. Chemosensory genes identified in the antennal transcriptome of the blowfly Calliphora stygia . BMC Genomics 16,, doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1466-8 (2015).

Liu, Y. et al. Identification of candidate olfactory genes in Leptinotarsa decemlineata by antennal transcriptome analysis. Frontiers Ecol. Evol. 3,, doi: 10.3389/fevo.2015.00060 (2015).

Liu, Y., Gu, S., Zhang, Y., Guo, Y. & Wang, G. Candidate olfaction genes identified within the Helicoverpa armigera antennal transcriptome. Plos ONE 7, e48260,, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048260 (2012).

Mitchell, R. F. et al. Sequencing and characterizing odorant receptors of the cerambycid beetle Megacyllene caryae . Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 42, 499–505 (2012).

Pitts, R., Rinker, D., Jones, P., Rokas, A. & Zwiebel, L. Transcriptome profiling of chemosensory appendages in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae reveals tissue- and sex-specific signatures of odor coding. BMC Genomics 12, 271 (2011).

Riveron, J., Boto, T. & Alcorta, E. Transcriptional basis of the acclimation to high environmental temperature at the olfactory receptor organs of Drosophila melanogaster . BMC Genomics 14, 259–259, doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-259 (2013).

Vosshall, L. B., Amrein, H., Morozov, P. S., Rzhetsky, A. & Axel, R. A spatial map of olfactory receptor expression in the Drosophila antenna. Cell 96, 725–736 (1999).

Guo, M. et al. Variant ionotropic receptors are expressed in olfactory sensory neurons of coeloconic sensilla on the antenna of the desert locust (Schistocerca gregaria). Int. J. Biol. Sci. 10, 1–14, doi: 10.7150/ijbs.7624 (2014).

Pitts, R. J., Liu, C., Zhou, X., Malpartida, J. C. & Zwiebel, L. J. Odorant receptor-mediated sperm activation in disease vector mosquitoes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 2566–2571, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322923111 (2014).

Andersson, M. et al. Sex- and tissue-specific profiles of chemosensory gene expression in a herbivorous gall-inducing fly (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae). BMC Genomics 15, 501 (2014).

Briscoe, A. D. et al. Female behaviour drives expression and evolution of gustatory receptors in butterflies. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003620,, doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003620 (2013).

Barbarossa, I. T., Muroni, P., Dardani, M., Casula, P. & Angioy, A. M. New insight into the antennal chemosensory function of Opius concolor (Hymenoptera: Braconidae). Italian J. Zool. 65, 367–370, doi: 10.1080/11250009809386775 (1998).

Lu, T. et al. Odor coding in the maxillary palp of the malaria vector mosquito Anopheles gambiae . Curr. Biol. 17, 1533–1544 (2007).

Montell, C. Gustatory receptors: not just for good taste. Curr. Biol. 23, R929–R932 (2013).

Benton, R., Vannice, K., Gomez-Diaz, C. & Vosshall, L. Variant ionotropic glutamate receptors as chemosensory receptors in Drosophila . Cell 136, 149–162 (2009).

Ochieng, S. A., Park, K. C., Zhu, J. W. & Baker, T. C. Functional morphology of antennal chemoreceptors of the parasitoid Microplitis croceipes (Hymenoptera: Braconidae). Arthropod Str. Dev. 29, 231–240 (2000).

Shiojiri, K., Takabayashi, J., Yano, S. & Takafuji, A. Flight response of parasitoids toward plant-herbivore complexes:A comparative study of two parasitoid-herbivore systems on cabbage plants. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 35, 87–92 (2000).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25, 402–408, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/meth.2001.1262 (2001).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by China Agriculture Research System (CARS-02) and the specific fund for Agro-Scientific Research in the public interest (201303026).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: T.A., T.Z. and Z.W. Performed the experiments: T.A. Analyzed the data: T.A. and T.Z. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: T.A., T.Z., K.H. and S.B. Wrote the paper: T.A., Z.W. and T.Z.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmed, T., Zhang, T., Wang, Z. et al. Gene set of chemosensory receptors in the polyembryonic endoparasitoid Macrocentrus cingulum. Sci Rep 6, 24078 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep24078

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep24078

This article is cited by

-

Antennal transcriptome analysis of olfactory genes and characterizations of odorant binding proteins in two woodwasps, Sirex noctilio and Sirex nitobei (Hymenoptera: Siricidae)

BMC Genomics (2021)

-

Sensory gene identification in the transcriptome of the ectoparasitoid Quadrastichus mendeli

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Identification of putative ingestion-related olfactory receptor genes in the Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir japonica sinensis)

Genes & Genomics (2021)

-

Functional insights from the GC-poor genomes of two aphid parasitoids, Aphidius ervi and Lysiphlebus fabarum

BMC Genomics (2020)

-

Identification and expression analysis of chemosensory receptor genes in an aphid endoparasitoid Aphidius gifuensis

Scientific Reports (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.