Abstract

As mesial temporal lobe epilepsy (mTLE) has been recognized as a network disorder, a longitudinal connectome investigation may shed new light on the understanding of the underlying pathophysiology related to distinct surgical outcomes. Resting-state functional MRI data was acquired from mTLE patients before (n = 37) and after (n = 24) anterior temporal lobectomy. According to surgical outcome, patients were classified as seizure-free (SF, n = 14) or non-seizure-free (NSF, n = 10). First, we found higher network resilience to targeted attack on topologically central nodes in the SF group compared to the NSF group, preoperatively. Next, a two-way mixed analysis of variance with between-subject factor ‘outcome’ (SF vs. NSF) and within-subject factor ‘treatment’ (pre-operation vs. post-operation) revealed divergent dynamic reorganization in nodal topological characteristics between groups, in the temporoparietal junction and its connection with the ventral prefrontal cortex. We also correlated the network damage score (caused by surgical resection) with postsurgical brain function and found that the damage score negatively correlated with postoperative global and local parallel information processing. Taken together, dynamic connectomic architecture provides vital information for selecting surgical candidates and for understanding brain recovery mechanisms following epilepsy surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mesial temporal lobe epilepsy (mTLE) is the most common type of epilepsy in adults1. Although epilepsy surgery is a highly effective treatment for drug-resistant mTLE patients, roughly 30% of surgically treated patients experience seizure recurrence2,3. Potential reasons for seizure relapse after surgery are complex, such as insufficient resection of epileptogenic tissue and widespread ipsilateral and bilateral temporal lobe functional and structural abnormalities4,5,6.

The risk factors associated with seizure recurrence are unknown, even the underpinning pathology is relatively clear in mTLE7. Certain features of the epileptogenic lesion, bilateral atrophy and remote lesions predict outcome: hippocampal volume asymmetry is a strong predictor of outcome8; ipsilateral diffuse hippocampal atrophy and contralateral regional hippocampal atrophy predict poor outcome9,10. Certain clinical features of the patient predict outcome: older age at surgery, longer epilepsy duration, secondary generalized seizures – all predict poor outcome11. But no features predict outcome with strong predictive value, therefore there must be further factors not yet identified.

As widespread structural and functional abnormalities are observed in mTLE12,13, it has been suggested that mTLE may be better characterized as a network disorder14,15. A recent anatomical study suggested that large-scale brain network organization may be a predictive factor for outcome16. Functional connectivity studies found abnormal topological organization in TLE17,18, suggesting that brain connectome is an effective way for understanding the functional alteration. Consequentially, assessing the global disturbances of brain function19,20, rather than evaluating the planned resection area in isolation, may shed new light on estimating probability of seizure freedom after surgery.

To characterize the brain recovery mechanism after surgery, a recent voxel-based morphometric study of seizure-outcome groups21 reported significant gray matter recovery in the seizure control group but little in the recurrence group21, suggesting that divergent postsurgical alterations in brain structure determine long-term recovery. However, the functional neural network reorganizations leading to seizure freedom or recurrence remain poorly understood22.

We aimed to describe the underlying explanation for distinct surgical outcomes using resting-state functional connectivity and graph theoretical analyses. Based on the previous demonstration that pre-surgical brain connections are related to postsurgical outcome16, we hypothesized that the successfulness of surgical resection (or attack) could be associated with the pre-surgical brain resilience. The resilience of the brain network, characterized by the degree to tolerance against targeted attacks, is usually associated with the stability of complex brain network23. It provides a quantitative insight into relevant network robustness against pathological attacks by disease24,25. Furthermore, we tracked the dynamic alteration of functional network after surgery and hypothesized that regions showing divergent reorganization in seizure-free and non-seizure-free groups may provide vital information for understanding distinct surgical outcomes.

Methods

Participants

A total of 37 patients with drug-resistant unilateral mTLE participated in this study. Mesial TLE was diagnosed according to International League Against Epilepsy 2001 criteria and based on a comprehensive preoperative evaluation, including seizure history and semiology, neurologic examination, diagnostic MR imaging and (video) electroencephalography. Detail of these clinical information for each patient was summarized in Table 1. All patients underwent standard anterior temporal lobectomy at Jinling Hospital from June 2009 to December 2013. All patients had hippocampal sclerosis ipsilateral to the seizure focus as revealed by MRI and confirmed by postoperative histopathology. We classified surgical outcome at least 1 year after surgery for all patients according to the Engel category. Patients were separated into two groups: seizure-free (Engel’s: I) with 23 patients (11 left-sided and 12 right-sided) and non-seizure-free (Engel’s: II, III and IV) with 14 patients (7 left-sided and 7 right-sided). Group demographic and clinical information are detailed in Table 2.

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was approved by the local medical ethics committee at Jinling Hospital, Nanjing University School of Medicine. All the methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Data acquisition

We acquired functional and structural images using a Siemens Trio 3T scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) at Jinling Hospital. Resting-state functional images were acquired using a single-shot, gradient-recalled echo planar imaging sequence (255 volumes, repetition time = 2000 ms, echo time = 30 ms, flip angle = 90°, field of view = 240 × 240 mm2, inter-slice gap = 0.4 mm, voxel size = 3.75 × 3.75 × 4 mm3, 30 transverse slices aligned along the anterior–posterior commissure). We instructed subjects simply to rest with their eyes closed, not to think of anything in particular and not to fall asleep. Foam padding was used to minimize head motion. Subsequently, we acquired high-resolution 3D T1-weighted anatomical images in the sagittal orientation using a magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo sequence (repetition time = 2300 ms, echo time = 2.98 ms, flip angle = 9°, field of view = 256 × 256 mm2, voxel size = 0.5 × 0.5 × 1 mm3, 176 slices without inter-slice gap). After scanning, subjects were asked whether they had fallen asleep during the scan.

Lesion mapping

Two investigators (J.G. J. and W. W.) independently traced the surgical lacuna manually on postoperative 3D T1-weighted anatomical images, creating an individual volume of interest (VOI) for each patient that was used to quantify the volume of resection. The degree of VOI overlap between investigators was estimated by the Dice coefficient (mean ± SD: 0.89 ± 0.04). The union of all the VOIs were finally used for further analysis (Fig. 1).

Data preprocessing

Functional image preprocessing was carried out using the DPARSF, REST (www.restfmri.net) and the SPM8 (www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) toolkits. We first flipped (left-to-right flipping) the images of right mTLE patients to allow analysis of both right and left mTLE patients as a homogeneous group, thereby improving statistical power and facilitating investigation of common pathophysiological mechanisms21. After exclusion of the first 5 dummy images, functional images were first corrected for temporal differences by slice-timing and for head motion by realignment. No translation or rotation parameters in any given data set exceeded ±1.5 mm or ±1.5°. Moreover, the mean frame-wise displacement (FD) was computed by averaging FD from every time point for each subject26. There was no difference in mean FD between the two patient groups (t = 0.32, P = 0.75). Spatial normalization of preoperative functional images was accomplished by 3D T1-based transformation. We coregistered the individual 3D T1 images to functional images. The 3D T1 images were segmented and normalized to Montreal Neurologic Institute (MNI) space by a 12-parameter nonlinear transformation. These transformation parameters were applied to preoperative functional images. For normalization of postoperative images, we additionally used a cost-function modification to exclude the area of the lacuna during the process and avoid bias during the transformations. The implementation of this processing is available in SPM8 and has been adopted in a number of studies on brain images with lesions21,27. After spatial normalization, pre- and postoperative functional images were resampled at 3 × 3 × 3 mm3 voxel size. To avoid introducing artificial correlations, no spatial smoothing was applied as previously suggested23,28,29.

To remove spurious sources of variance, functional images were preprocessed as follows: first, linear trends were removed from time series and temporal band-pass filtering (0.01–0.08 Hz) was performed; second, 24 head motion parameters30, averaged signals from cerebrospinal fluid, white matter and global brain signals were removed by regression31,32,33.

Reconstruction of functional brain networks

Anatomical parcellation

To determine the nodes of the functional network, we used the Harvard-Oxford Atlas (HOA) (112 non-cerebellar anatomical regions of interest [ROIs])34. Here we excluded the brainstem, resulting in 55 ROIs for each hemisphere. This coarse parcellation scheme is referred to as HOA-110 (Fig. 1, Table S1). Considering that the range of nodal scales may result in considerable variation of graph theoretical parameters of the functional network29,35, we also used a high-resolution parcellation network with 512 ROIs of approximately equal size across both hemispheres (http://andrewzalesky.com)36. This fine-grained parcellation scheme is referred to as HOA-512. These two parcellation schemes were applied in parallel to the following network analyses for cross-validation of our results.

Network construction

We obtained a temporal correlation matrix (of elements rij) for each subject by computing Pearson correlation coefficients between the processed time series of every pair of ROIs. To construct weighted functional connectivity networks, weighted edges (w) were incorporated, representing absolute functional connectivity strength values between connected ROIs, e.g. wij = |Zij|, where Zij is the transformed correlation coefficient for node i and j by Fisher’s Z transformation.

Network topology analysis

We evaluated the following global network measures: total connection strength (Snet), overall clustering coefficient (Cnet), global efficiency (Enet) and small-worldness (Sigma). Nodal topological characteristics were also calculated for each node, including nodal efficiency (Ei), nodal clustering coefficient (Ci) and betweenness centrality (BCi). The definition and interpretation of these metrics are described in the Supplementary Material.

Statistical Analyses

To examine whether functional network architecture is distinct in seizure-free and non-seizure-free groups before surgery and how functional network architecture reorganized after surgery, we performed two types of analyses including the following steps (Fig. 2). To examine the effect of surgical lacuna on postsurgical brain function, we also correlated the surgical damage score (DS)37,38 and small-worldness of the postsurgical networks.

Overview of the analytic strategy.

First, cortical and subcortical brain regions were parcellated according to the Harvard-Oxford atlas. Next, a weighted connectivity matrix was constructed from preprocessed functional data. Then, we compared the preoperative functional connectome of seizure-free and non-seizure-free groups (Analysis I); and performed two-way mixed ANOVA for the pre- and postoperative functional connectomes of the two patient groups (Analysis II).

Network resilience analysis (analysis I)

We evaluated the resilience of the networks by random failure and targeted attack analysis23,39 for both HOA-110 and HOA-512 schemes. The network cost is defined as the total number of connections divided by the number of all possible connections. We selected a fixed cost (=0.14) that ensured the largest connected component of each functional connectivity network (>95%) with a minimum number of spurious edges40.

In random failure analysis, we successively removed randomly chosen nodes until complete network dissolution. This step was repeated 1000 times23,39. In targeted attack analysis, we first computed the node BCi for all nodes in the network. Then we removed the node with the highest BCi. All BCi values were then re-computed and again the node with the highest BCi was removed until one last node remained23,39. For both random failure and targeted attack analysis, the number of nodes removed per step was set to one for the HOA-110 network and four for the HOA-512 network. At each step after random or targeted node removal, we calculated network measures, including the size of the largest connected component, overall clustering coefficient (Cnet) and global efficiency (Enet) of the remaining network.

Network resilience was compared between patient groups using two-sample t-test. We corrected the statistical significance for multiple comparisons using a false-positive adjustment. Specifically, we set p < (1/n), where n corresponds to the number of network node removal steps as described in our previous study41. This implies accepting less than one false-positive per analysis35,42. Further, we also calculated the area under the curve (AUC) for network resilience, providing an overall resilience estimate independent of the number of steps (node removals) required for network dissolution during random failure or targeted attack analysis.

Dynamical functional network reorganization (analysis II)

To examine how functional architecture reorganized according to surgical outcome (seizure-free or non-seizure-free), we performed a two-way mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) (http://mrtools.mgh.harvard.edu/index.php/GLM_Flex) for network measures. The between-subject ‘random’ factor was ‘outcome’ (seizure-freedom vs. non-seizure-freedom) and the within-subject ‘fixed’ factor was ‘treatment’ (pre-operation vs. post-operation). To compare brain networks between groups, they must have the same number of nodes (ROIs)43. For both pre- and postoperative data, we excluded ROIs that overlapped with the surgical lacuna, resulting in 96 non-damaged ROIs for the HOA-110 network and 474 non-damaged ROIs for the HOA-512 network.

For connectivity-based (edge) statistics, the significant edges in the correlation matrix (present at least in one of the four group datasets) were entered into a two-way mixed ANOVA. The statistical significance for an interaction effect was corrected using a false-positive adjustment35,42. Specifically, we set p < (1/n), where n is the number of edges.

For global and nodal topological characteristics statistics, we selected a range of cost threshold (0.10 ≤ cos t ≤ 0.35, step = 0.01) for functional connectivity networks in both the HOA-110 and HOA-512 schemes since there is currently no formal consensus regarding selection of thresholds43. Further, we calculated the AUC for the global and nodal network metrics, providing an overall estimate for the topological characterization of brain networks independent of cost threshold. Finally, the AUC of global and nodal topological characteristics were entered into a two-way mixed ANOVA. The statistical significance for an interaction effect was corrected using a false-positive adjustment35,42. Specifically, we set p < (1/n), where n corresponds to the number of nodes.

Surgical damage associated with postoperative small-worldness

We correlated the surgical DS and the AUC for small-worldness (0.10 ≤ cos t ≤ 0.35, step = 0.01) of the postoperative networks. The DS was computed as in previous studies37,38 with some modifications. First, the extent of the surgical lacuna for each individual was quantified by counting the percentage of voxels in each network ROI that overlapped with the lacuna. Second, each percentage was then multiplied by the preoperative nodal topological characteristics (Ei and Ci) of the corresponding ROI, resulting in one value for each damaged ROI. The processes can be expressed as follows:

where N is the number of ROIs damaged by surgery and i is one of these ROIs. C.E. represents the preoperative node feature (Ci or Ei) of the given ROI. We calculated two DS values, Ci-based and Ei-based, depending on the nodal feature and correlated Ci- and Ei-based DS values with postoperative small-worldness using Pearson’s correlation (P < 0.05).

Results

Clinical data

There were no significant differences in preoperative or postoperative values between groups, including mean age, gender proportion, seizure onset age and duration of epilepsy. Importantly, the volume of the surgical lacuna in the seizure-free group did not differ from that in the non-seizure-free group (t = 0.39, P = 0.70) (Table 2).

Network resilience before surgery

The two surgical outcome groups showed similar network resilience to random failure but differential resilience to targeted attack. Using the HOA-110 parcellation scheme, we found that the seizure-free group exhibited a higher resilience of the largest component and greater Enet across a large range of steps (node removals) compared to the non-seizure-free group (P < 0.05 corrected for multiple comparisons) (Fig. 3). Comparison of the AUC also showed higher resilience of the largest component and greater Enet in the seizure-free group. No significant difference was found for the resilience of Cnet. Using the HOA-512 parcellation scheme, all these findings were well reproduced (Fig. S1).

Network resilience analysis.

Graphs display the network features as a function of removed nodes. All the features (largest component, clustering coefficient and global efficiency) were normalized to the measures obtained from the intact network. “Asterisks” illustrate measures that were statistically significant between seizure-free and non-seizure-free groups for each level network attack (P < 0.05 corrected). Shaded bands denote SEM across subjects. Bar graphs represent the resilience of the area under the curve of patient groups.

Network reorganization after surgery

In analysis II, we investigated how brain functional architecture reorganized in patients achieving seizure freedom compared to those who did not. With the HOA-110 parcellation scheme, we observed a significant ‘outcome’ × ‘treatment’ interaction for edges (Fig. 4). The two patient groups showed divergent alterations after surgery in two edges (all interaction effect, P < 0.05 corrected for multiple comparisons across all edges) connecting left parietal operculum cortex (POC) and left frontal medial cortex (FMC) (F = 15.75, P = 0.0007), right POC and right FMC (F = 17.68, P = 0.0004). Significant ‘outcome’ main effect of connectivity was found between right subcallosal cortex and anterior division of left supramarginal gyrus (with higher strength in seizure-free patients; t = 3.80, P = 4.5 × 10−4). ‘Treatment’ main effect indicated connections increased after surgery between: right frontal operculum cortex and left Heschls gyrus (t = 4.09, P = 2.4 × 10−4), posterior division of right superior temporal gyrus and left Heschls gyrus (t = 4.48, P = 9.3 × 10−5), posterior division of left cingulate gyrus and bilateral cuneal cortex (left, t = 4.21, P = 1.8 × 10−4; right, t = 3.99, P = 3.1 × 10−4), left supracalcarine cortex and right precuneus cortex (t = 3.95, P = 3.4 × 10−4) (Fig. S2).

Interaction effect (treatment by outcome) for network edges.

(A,B) The pre- (lower diagonal) and postoperative (upper diagonal) correlation matrix for seizure-free (A) and non-seizure-free groups (B). (C) Two connections (edges) with significant interaction effects are shown in a 3D brain template (P < 0.05 corrected) by line segment in red. Line graphs show how these connections were altered by surgery in each group. (D) Matrix showing connections with significant interaction effect, both corrected (in red) and uncorrected (colored blue to yellow). Columns and rows (nodes) of the matrices are ordered and colored according to six distinct functional modules (Fig. 1, Table S1). The nodes damaged by surgery are shown in gray. PO.L = left parietal operculum cortex, FMC.L= left frontal medial cortex, PO.R = right parietal operculum cortex, SC.R = right subcallosal cortex, PO.L = left parietal operculum cortex.

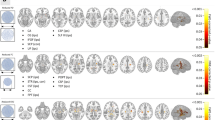

The AUC of nodal topological characteristics (efficiency, clustering coefficient and betweenness centrality) were entered separately into a two-way mixed ANOVA. With the HOA-110 parcellation scheme, we observed significant ‘outcome’ × ‘treatment’ interaction (P < 0.05 corrected for multiple comparisons across all ROIs) of BCi (in left occipital pole [OP] [F = 9.26, P = 0.006]) and Ci (in left angular gyrus [F = 8.06, P = 0.01]) (Fig. 5). Ei did not show a significant ‘outcome’ × ‘treatment’ interaction. The HOA-512 parcellation scheme yielded similar interaction effect in bilateral temporal nodes (Fig. S3). No significant group main effect was found. Significant time main effect was found in left precuneus cortex (with decreased BCi after surgery; t = −3.04, P = 0.003) (Fig. S4).

Interaction effect (treatment by outcome) for network nodes.

Two nodes show a significant interaction effect. Line graphs show how the two nodes are altered by surgery in each group. The spheres are classified into six modules and colored as in Fig. 1.

For global topological characteristics, only Snet showed significant interaction effect in both the HOA-110 (F = 4.84, P = 0.04) and the HOA-512 (F = 4.12, P = 0.05) parcellation scheme. Post-hoc analysis indicated NSF patients showed higher Snet than SF patients (t = 2.65, P = 0.01 for HOA-110; t = 2.47, P = 0.02 for HOA-512). No significant interaction and main effect was observed for all the other global characteristics.

Surgical damage and postoperative network properties

There was no significant group difference in Ei-based damage score (t = 0.17, P = 0.87), consistent with the approximately equal mean lacuna volumes. In contrast, Ci-based damage score (t = 2.17, P = 0.04) was higher in NSF patients. In addition, we found that the small-worldness of the postoperative brain functional network negatively correlated with both Ei-based (r = −0.51, P = 0.01) and Ci-based (r = −0.45, P = 0.03) damage score (Fig. 6).

Clinical damage and postsurgical small-worldness.

(A) The matrix shows the percentage of each node damaged in each subject. To illustrate how this was percentage computed, the resected volumes of one subject are overlapped on a flat surface with red circles showing the border of the damaged ROIs. (B) Both Ei- and Ci-based damage scores are significantly and negatively correlated with the postsurgical small-worldness (sigma). STGant. = anterior part of superior temporal gyrus, STGpost. = posterior part of superior temporal gyrus, ITGant. = anterior part of inferior temporal gyrus, ITGpost. = posterior part of inferior temporal gyrus, TFant. = anterior part of temporal fusiform cortex, TFpost. = posterior part of temporal fusiform cortex, PP. = planum polare, MTGant. = anterior part of middle temporal gyrus, TP. = temporal pole, PHant. = anterior part of parahippcampal gyrus, PHpost. Posterior part of parahippcampal gyrus, Hip. = hippocampus, Amy. = amygdala, L = left hemisphere. Ei and Ci represent the global efficiency and clustering coefficient respectively.

Discussion

A core characteristic of epilepsy is the excessively spontaneous neuronal activity. Resting-state fMRI, particularly focusing on the spontaneous brain activity, has particular advantage to illustrate functional alteration in epileptic brain. Using resting-state fMRI, a number of studies discussed the epileptic network, trying to characterize the pathophysiology mechanism44,45,46,47,48,49, uncover the neuronal mechanism of cognitive deficit50, or discriminate epilepsy patients from heathy subjects51. In the current study, we focused on the brain functional feature in patients with distinct surgical outcomes. Using resting-state fMRI and graph-based network analysis, we revealed the functional connectomic features in mTLE patients with distinct surgical outcomes. Preoperatively, the seizure-free group showed higher network resilience than the non-seizure-free group, underscoring the potential predictive value of this global network measurement. Furthermore, the two surgical outcome groups exhibited divergent postsurgical reorganization of nodal topological characteristics, mainly in the temporoparietal junction (TPJ), as well in its connection with ventral prefrontal cortex, suggesting that changes in extratemporal circuits associating with recovery and relapse. Finally, postoperative network property was negatively associated with surgical damage. These findings extend our understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the distinct outcomes of mTLE surgery.

Presurgical resilience to network perturbation

A comprehensive presurgical assessment of mTLE patients is crucial to weigh the possible benefits (e.g., seizure control) against the risks (e.g., postsurgical complications or cognitive deficits)52. Many neuroimaging studies have sought to predict the extent of seizure control and cognitive damage after surgery21,39,53,54,55,56. Bonilha and colleagues reported a relationship between the small-worldness of the presurgical structural network in mTLE patients and surgical outcome16. In the current study, we found that the largest component and global efficiency of seizure-free patients showed higher resilience to targeted attack than non-seizure-free patients, regardless of the parcellation scheme (HOA-110 or HOA-512). Targeted attack measures the brain resilience to simulated sequential elimination of topologically central nodes23, suggesting that pathological attack on the network hub will have a disproportionately larger impact on network information processing57. Targeted attack analysis has been applied to a number of clinical disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease24 and autism25. Previous network studies found that mTLE patients showed abnormal resilience to targeted attack for both structural39 and functional networks58. We found a significant association between brain network resilience and surgical outcome, suggesting that there are more or stronger connections in seizure-free patients25, allowing enduring network integrity even after attack. These abundant connections could be a long-term result of recurrent seizures. In contrast, clustering coefficient resilience was not significantly different between patient groups, suggesting that the extent of local network cliquishness or efficiency of information transfer59 is as robust in non-seizure-free patients as in seizure-free patients and further that the predictive value of clustering coefficient resilience is limited.

Dynamic alterations of regional/connectivity characteristics

To elucidate brain functional network reorganization patterns leading to seizure freedom or recurrence, we compared the dynamic alterations of seizure-free patients to those of non-seizure-free patients. The results are in accordance with previous studies demonstrating that the ventral PFC is a vital part of the epileptogenic network60,61,62. Using depth electrodes to record seizure propagation in mTLE patients, Lieb et al.60 observed a common pattern, with the seizure initially invading the ipsilateral ventral PFC and then spreading to the contralateral side60. A neuroimaging study adopting diffusion tensor imaging tractography found decreased structural connectivity between ipsilateral frontal and temporal cortices in mTLE patients61. In line with this result, we found that increased functional connectivity between ventral medial PFC and TPJ following surgery was associated with seizure freedom. A PET study found that the metabolic activities of the ventral PFC and temporal lobe were abnormal in mTLE patients62. In addition, we found a divergent alteration in ipsilateral TPJ (the Ci of the angular gyrus) between the two patient groups. Using the finer HOA-512 parcellation scheme, we confirmed the findings in the TPJ area. Both ventral medial PFC and TPJ are belong to the default mode network (DMN). The abnormal function of DMN in mTLE patients has been reported in local activity47, within-network connectivity63 and causal connectivity with mesial temporal lobe44. Our findings further suggested the postoperative functional alteration of DMN may be an important biomarker for surgical outcome. Although anterior temporal lobectomy can ameliorate drug-resistant mTLE, 60–100% of patients will suffer a postoperative visual field defect64. Left occipital pole, a central pivot of the visual system, showed divergent alterations, implicating the disruption of visual system may be different between SF and NSF patients.

Clinical damage and postsurgical small-worldness

To examine whether postoperative brain function was related to surgical damage, we computed a damage score for each patient and analyzed the correlation with the postoperative network small-worldness (sigma) value across patients. As in the study of Gratton et al.37, this damage score not only reflected the size of the surgical lacuna but also the function importance of the damaged cortical regions. In our study, postoperative small-worldness decreased as the damage score increased, implying that surgeons may be able to predict postsurgical function if they can precisely outline the resection area before surgery. The small-worldness of human brain networks has been related to a number of cognitive processes, such as intelligence65, memory66 and attention67. Future studies should examine the association of the damage score with more specific cognitive functions using behavioral measures.

Methodological considerations

Large-scale brain connectome modeling and analysis is a rapidly developing research field, but there are still controversies concerning optimal analytic strategies68. Thus, the present brain functional network analysis employed several parallel schemes. First, two resolution parcellation schemes were used to cross-validate our findings. However, analysis still produced some inconsistent results. Such divergence may result from the different node scales36,69. Second, in this study we used weighted networks, reflecting heterogeneity in capacity and strength of connectivity, but binary networks are simpler to use for statistical comparisons70. Finally, we used multiple cost thresholds to evaluate the stability of the topological organization in brain functional networks because there is currently no formal consensus regarding cost threshold selection.

Limitations

The present results should be interpreted in the context of the study limitations. First, due to the small sample size, we grouped left and right mTLE patients into one group, although previous studies suggested that the side of seizure onset influences the abnormal connectivity features of mTLE58,71. Thus, our findings should be understood as revealing pathophysiology changes common to left and right mTLE rather than mechanisms specific for left or right mTLE patients. Second, the interval between operation and follow-up MRI examination was relatively short. As the outcome may change even after 10 years72, a longer-term longitudinal study is necessary. Third, although we balanced the major demographic and clinical factors between groups (age, gender proportion, volume of surgical lacuna and follow-up interval), preoperative cognitive functions, such as memory and language ability, were not examined53,73. Finally, all the findings were derived from group-level statistical results. To what extent these findings can be applied for individual preoperative estimates requires further investigation.

Conclusions

In current study, we combined resting-state functional connectivity and graph theoretical approaches to investigate the pathophysiology of mTLE patients with different surgical outcomes. Relatively high preoperative network resilience could provide complementary information to screen for patients most likely to achieve seizure freedom after surgery. Re-wiring of the ventral prefrontal cortex and temporoparietal junction area appears to be the predominant postsurgical functional reorganization mechanism influencing outcome. In summary, these findings may help to establish better surgical referral criteria and contribute to our understanding of brain recovery following surgery for mTLE.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Liao, W. et al. Functional Connectome before and following Temporal Lobectomy in Mesial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Sci. Rep. 6, 23153; doi: 10.1038/srep23153 (2016).

References

Kwan, P., Schachter, S. C. & Brodie, M. J. Drug-resistant epilepsy. N Engl J Med 365, 919–926 (2011).

Wiebe, S., Blume, W. T., Girvin, J. P. & Eliasziw, M. A randomized, controlled trial of surgery for temporal-lobe epilepsy. N Engl J Med 345, 311–318 (2001).

de Tisi, J. et al. The long-term outcome of adult epilepsy surgery, patterns of seizure remission and relapse: a cohort study. Lancet 378, 1388–1395 (2011).

Spencer, S. & Huh, L. Outcomes of epilepsy surgery in adults and children. Lancet Neurol 7, 525–537 (2008).

Bonilha, L. et al. Does resection of the medial temporal lobe improve the outcome of temporal lobe epilepsy surgery? Epilepsia 48, 571–578 (2007).

Keller, S. S. et al. Persistent seizures following left temporal lobe surgery are associated with posterior and bilateral structural and functional brain abnormalities. Epilepsy Res 74, 131–139 (2007).

Wang, Z. I. et al. The pathology of magnetic-resonance-imaging-negative epilepsy. Mod Pathol 26, 1051–1058 (2013).

Jack, C. R. Jr. et al. Magnetic resonance image-based hippocampal volumetry: correlation with outcome after temporal lobectomy. Ann Neurol 31, 138–146 (1992).

Lin, J. J. et al. Three-dimensional preoperative maps of hippocampal atrophy predict surgical outcomes in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology 65, 1094–1097 (2005).

Li, L. M. et al. Surgical outcome in patients with epilepsy and dual pathology. Brain 122 (Pt 5), 799–805 (1999).

Janszky, J. et al. Temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal sclerosis: predictors for long-term surgical outcome. Brain 128, 395–404 (2005).

Keller, S. S. & Roberts, N. Voxel-based morphometry of temporal lobe epilepsy: an introduction and review of the literature. Epilepsia 49, 741–757 (2008).

Nelissen, N. et al. Correlations of interictal FDG-PET metabolism and ictal SPECT perfusion changes in human temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal sclerosis. Neuroimage 32, 684–695 (2006).

Engel, J. Jr. et al. Connectomics and epilepsy. Curr Opin Neurol 26, 186–194 (2013).

Richardson, M. P. Large scale brain models of epilepsy: dynamics meets connectomics. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 83, 1238–1248 (2012).

Bonilha, L. et al. Presurgical connectome and postsurgical seizure control in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology 81, 1704–1710 (2013).

Liao, W. et al. Altered functional connectivity and small-world in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. PLoS One 5, e8525 (2010).

Vlooswijk, M. C. et al. Loss of network efficiency associated with cognitive decline in chronic epilepsy. Neurology 77, 938–944 (2011).

Park, H. J. & Friston, K. Structural and functional brain networks: from connections to cognition. Science 342, 1238411 (2013).

Craddock, R. C. et al. Imaging human connectomes at the macroscale. Nature methods 10, 524–539 (2013).

Yasuda, C. L. et al. Dynamic changes in white and gray matter volume are associated with outcome of surgical treatment in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuroimage 49, 71–79 (2010).

Gleissner, U., Sassen, R., Schramm, J., Elger, C. E. & Helmstaedter, C. Greater functional recovery after temporal lobe epilepsy surgery in children. Brain 128, 2822–2829 (2005).

Achard, S., Salvador, R., Whitcher, B., Suckling, J. & Bullmore, E. A resilient, low-frequency, small-world human brain functional network with highly connected association cortical hubs. J Neurosci 26, 63–72 (2006).

He, Y., Chen, Z. & Evans, A. Structural insights into aberrant topological patterns of large-scale cortical networks in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci 28, 4756–4766 (2008).

Peters, J. M. et al. Brain functional networks in syndromic and non-syndromic autism: a graph theoretical study of EEG connectivity. BMC medicine 11, 54 (2013).

Power, J. D., Barnes, K. A., Snyder, A. Z., Schlaggar, B. L. & Petersen, S. E. Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks arise from subject motion. Neuroimage 59, 2142–2154 (2012).

Stebbins, G. T. et al. Gray matter atrophy in patients with ischemic stroke with cognitive impairment. Strok e 39, 785–793 (2008).

Salvador, R., Suckling, J., Schwarzbauer, C. & Bullmore, E. Undirected graphs of frequency-dependent functional connectivity in whole brain networks. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 360, 937–946 (2005).

Wang, J. et al. Parcellation-dependent small-world brain functional networks: a resting-state fMRI study. Hum Brain Mapp 30, 1511–1523 (2009).

Friston, K. J., Williams, S., Howard, R., Frackowiak, R. S. & Turner, R. Movement-related effects in fMRI time-series. Magn Reson Med 35, 346–355 (1996).

Fox, M. D. et al. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102, 9673–9678 (2005).

Fox, M. D., Zhang, D., Snyder, A. Z. & Raichle, M. E. The global signal and observed anticorrelated resting state brain networks. J Neurophysiol 101, 3270–3283 (2009).

Zhang, Z. et al. Altered functional-structural coupling of large-scale brain networks in idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Brain 134, 2912–2928 (2011).

Smith, S. M. et al. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage 23 Suppl 1, S208–219 (2004).

Fornito, A., Yoon, J., Zalesky, A., Bullmore, E. T. & Carter, C. S. General and specific functional connectivity disturbances in first-episode schizophrenia during cognitive control performance. Biol Psychiatry 70, 64–72 (2011).

Zalesky, A. et al. Whole-brain anatomical networks: does the choice of nodes matter? Neuroimage 50, 970–983 (2010).

Gratton, C., Nomura, E. M., Perez, F. & D’Esposito, M. Focal brain lesions to critical locations cause widespread disruption of the modular organization of the brain. J Cogn Neurosci 24, 1275–1285 (2012).

Nomura, E. M. et al. Double dissociation of two cognitive control networks in patients with focal brain lesions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107, 12017–12022 (2010).

Bernhardt, B. C., Chen, Z., He, Y., Evans, A. C. & Bernasconi, N. Graph-theoretical analysis reveals disrupted small-world organization of cortical thickness correlation networks in temporal lobe epilepsy. Cereb Cortex 21, 2147–2157 (2011).

Achard, S. & Bullmore, E. Efficiency and cost of economical brain functional networks. PLoS Comput Biol 3, e17 (2007).

Liao, W. et al. Relationship between Large-scale Functional and Structural Covariance Networks in Idiopathic Generalized Epilepsy. Brain Connect 3, 240–254 (2013).

Lynall, M. E. et al. Functional connectivity and brain networks in schizophrenia. J Neurosci 30, 9477–9487 (2010).

Bullmore, E. T. & Bassett, D. S. Brain graphs: graphical models of the human brain connectome. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 7, 113–140 (2011).

Ji, G. J. et al. Disrupted causal connectivity in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. PLoS One 8, e63183 (2013).

Ji, G. J. et al. Connectome Reorganization Associated With Surgical Outcome in Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Medicine (Baltimore) 94, e1737 (2015).

Ji, G. J. et al. Generalized tonic-clonic seizures: aberrant interhemispheric functional and anatomical connectivity. Radiology 271, 839–847 (2014).

Zhang, Z. et al. fMRI study of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy using amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation analysis. Hum Brain Mapp 31, 1851–1861 (2010).

Wu, Y. et al. Local Activity and Causal Connectivity in Children with Benign Epilepsy with Centrotemporal Spikes. PLoS One 10, e0134361 (2015).

Luo, C. et al. Disrupted functional brain connectivity in partial epilepsy: a resting-state fMRI study. PLoS One 7, e28196 (2011).

Wu, Y. et al. Interhemispheric Connectivity in Drug-Naive Benign Childhood Epilepsy With Centrotemporal Spikes: Combining Function and Diffusion MRI. Medicine (Baltimore) 94, e1550 (2015).

Zhang, Z. et al. Pathological uncoupling between amplitude and connectivity of brain fluctuations in epilepsy. Hum Brain Mapp 36, 2756–2766 (2015).

Spencer, S. S. Long-term outcome after epilepsy surgery. Epilepsia 37, 807–813 (1996).

Bonelli, S. B. et al. Memory reorganization following anterior temporal lobe resection: a longitudinal functional MRI study. Brain 136, 1889–1900 (2013).

Cheung, M. C., Chan, A. S., Lam, J. M. & Chan, Y. L. Pre- and postoperative fMRI and clinical memory performance in temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 80, 1099–1106 (2009).

Negishi, M., Martuzzi, R., Novotny, E. J., Spencer, D. D. & Constable, R. T. Functional MRI connectivity as a predictor of the surgical outcome of epilepsy. Epilepsia 52, 1733–1740 (2011).

Xu, Q. et al. Time-Shift Homotopic Connectivity in Mesial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 35, 1746–1752 (2014).

Crossley, N. A. et al. The hubs of the human connectome are generally implicated in the anatomy of brain disorders. Brain 137, 2382–2395 (2014).

Wang, J. et al. Graph theoretical analysis reveals disrupted topological properties of whole brain functional networks in temporal lobe epilepsy. Clin Neurophysiol 125, 1744–1756 (2014).

He, Y. & Evans, A. Graph theoretical modeling of brain connectivity. Curr Opin Neurol 23, 341–350 (2010).

Lieb, J. P., Dasheiff, R. M. & Engel, J. Jr. Role of the frontal lobes in the propagation of mesial temporal lobe seizures. Epilepsia 32, 822–837 (1991).

Lin, J. J., Riley, J. D., Juranek, J. & Cramer, S. C. Vulnerability of the frontal-temporal connections in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 82, 162–170 (2008).

Chassoux, F. et al. Metabolic changes and electro-clinical patterns in mesio-temporal lobe epilepsy: a correlative study. Brain 127, 164–174 (2004).

Hsiao, F. J. et al. Increased Intrinsic Connectivity of the Default Mode Network in Temporal Lobe Epilepsy: Evidence from Resting-State MEG Recordings. PLoS One 10, e0128787 (2015).

Barton, J. J., Hefter, R., Chang, B., Schomer, D. & Drislane, F. The field defects of anterior temporal lobectomy: a quantitative reassessment of Meyer’s loop. Brain 128, 2123–2133 (2005).

Wu, K. et al. Topological organization of functional brain networks in healthy children: differences in relation to age, sex and intelligence. PLoS One 8, e55347 (2013).

Langer, N., von Bastian, C. C., Wirz, H., Oberauer, K. & Jancke, L. The effects of working memory training on functional brain network efficiency. Cortex 49, 2424–2438 (2013).

Cao, M., Shu, N., Cao, Q., Wang, Y. & He, Y. Imaging Functional and Structural Brain Connectomics in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Mol Neurobiol 50, 1111–1123 (2014).

Wig, G. S., Schlaggar, B. L. & Petersen, S. E. Concepts and principles in the analysis of brain networks. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1224, 126–146 (2011).

Fornito, A., Zalesky, A. & Bullmore, E. T. Network scaling effects in graph analytic studies of human resting-state FMRI data. Front Syst Neurosci 4, 22 (2010).

Rubinov, M. & Sporns, O. Complex network measures of brain connectivity: Uses and interpretations. Neuroimage 52, 1059–1069 (2010).

Besson, P. et al. Structural connectivity differences in left and right temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuroimage 100, 135–144 (2014).

Sadek, A. R. & Gray, W. P. Chopping and changing: long-term results of epilepsy surgery. Lancet 378, 1360–1362 (2011).

Stretton, J. et al. Working memory network plasticity after anterior temporal lobe resection: a longitudinal functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Brain 137, 1439–1453 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the participants in this study. We thank the generous funding from the Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 81401400 to G.J.J., 81401402 to Q.X., 81201155 and 81471653 to W.L., 81271553 and 81422022 to Z.Z., 81301198 to Z.W., 81201078 to F.Y. and 81020108022 and 31471084 to Y.F.Z), the UK Medical Research Council Programme grant (grant number MR/K013998/1 to MP.R), the Grants for Young Scholar in Jinling Hospital (grant numbers. Q2008063, 2011060 to Z.Z), the 863 Project (grant number 2015AA020505 to Z.Z); the Qian Jiang Distinguished Professor program to Y.F.Z. and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant numbers. 2013M532229 to W.L.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.L., G.-J.J. and Z.Z.: manuscript drafting; Y.-F.Z., K.S., W.L. and G.L.: study design; G.-J.J. and W.L.: data analyses and interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; M.P.R.: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; Q.X., W.W., J.W., Z.W., F.Y. and Q.J.: data collection and preliminary analyses of clinical data; W.L., Z.Z. and G.L.: study supervision, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Liao, W., Ji, GJ., Xu, Q. et al. Functional Connectome before and following Temporal Lobectomy in Mesial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Sci Rep 6, 23153 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep23153

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep23153

This article is cited by

-

Dynamic functional connectivity in temporal lobe epilepsy: a graph theoretical and machine learning approach

Neurological Sciences (2021)

-

Recent Advances in Neuroimaging of Epilepsy

Neurotherapeutics (2021)

-

Large-scale resculpting of cortical circuits in children after surgical resection

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Identification of neural networks preferentially engaged by epileptogenic mass lesions through lesion network mapping analysis

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Recent developments in cognitive fMRI for temporal lobe epilepsy

Zeitschrift für Epileptologie (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.