Abstract

We first report a simple nanoplasmonic sensor for both universal and slow-light sensing in a Fano resonance-based waveguide system. A theoretical model based on the coupling of resonant modes is provided for the inside physics mechanism, which is supported by the numerical FDTD results. The revealed evolution of the sensing property shows that the Fano asymmetric factor p plays an important role in adjusting the FOM of sensor and a maximum of ~4800 is obtained when p = 1. Finally, the slow-light sensing in such nanoplasmonic sensor is also investigated. It is found that the contradiction between the sensing width with slow-light (SWS) and the relevant sensitivity can be resolved by tuning the Fano asymmetric factor p and the quality factor of the superradiant mode. The presented theoretical model and the pronounced features of this simple nanoplasmonic sensor, such as the tunable sensing and convenient integration, have significant applications in integrated plasmonic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the surface plasmons (SPs) can overcome the diffraction limit and manipulate light in nanoscale domain, they provide possibility for nanodevices with extraordinary properties, high miniaturization and integration1. Plasmonic sensor is a kind of nanoscale device by utilizing the extreme sensitivity of SPs to the surrounding dielectric environment2. The Fano resonance results from the coupling effect between a wide continent state and a narrow distinct state, leading to the sharp and asymmetric spectral line shape and small perturbations can induce dramatic intensity variation or spectrum shifts3. Thus it can be used in the areas of nonlinearities, lasing, modulators and biosensors4,5. Large amount of researches have been devoted to generating the Fano resonances and studied the related sensing properties in various plasmonic structures6,7,8,9,10, such as nanoparticle clusters6, metamaterials7 and non-concentric cavity8 in the past several years. As another special property of the Fano resonance, the light speed in a Fano system can be significantly slowed down due to the steep phase dispersion11,12, which can enhance the light intensity by reason of the pulse compression. This unique characteristic can improve the sensing due to the increased light-mater interaction13. Huang et al. reported an enhanced sensor in a plasmonic waveguide14 and Wen et al. also studied the sensing with slow light in a fiber Bragg grating15. Here for clarity, we consider the former sensing in6,7,8 as universal sensing. Thus the Fano system possesses both the universal and the slow light sensing. However, those structures were either too bulky, complicated, or lossy, which are adverse to the compact and integrated device research.

Recently, plasmonic metal-dielectric-metal (MDM) waveguide have attracted people’s tremendous attention due to its remarkable advantages of long propagation distance, easy fabrication and wide available frequency range16,17, it can also be used for sensor applications18,19,20,21. For example, Lu et al. studied the plasmonic sensor in a MDM waveguide coupling with stubs19. Zafar et al. reported the enhanced figure of merit in a Fano resonance-based plasmonic sensor21. Nevertheless, these works mainly focused on the sensing performance numerically, no further discussion on regulating the figure of merit (FOM) of sensor19. In order to find out the effective factors those relate to the FOM and achieve the optimization of sensing properties, we need to establish theoretical models. However, still little attention is paid to the theoretical research on tuning both the universal and the slow light sensing properties in cavity coupled MDM waveguide system.

In this paper, we show a nanoplasmonic sensor based on the Fano resonance in a MDM waveguide systematically, it can be applied for both the universal and the slow-light sensing. The sensor is accurately tunable and the Fano asymmetric factor p is crucial to adjust the FOM of sensor. The contradiction in the slow-light sensing is discussed in details and can be solved by tuning the quality factor of the superradiant mode and the Fano asymmetric factor p. The presented theoretical model and the pronounced features of this simple plasmonic sensor, such as the tunable sensing and convenient integration, have significant applications in integrated compact plasmonic devices.

Structure and analytic theory

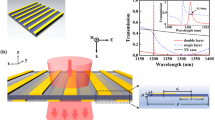

The schematic of the nanoplasmonic sensor is shown in Fig. 1(a). In this plasmonic system, the lower cavity with length L2 couples efficiently to the input wave in the bus waveguide thus be strongly excited, forming a wide continent spectrum. However, the upper cavity with length L1 couples weakly to the input wave and leads to a narrow discrete one. They can be analogously regarded as the superradiant mode and subradiant mode in forming the Fano resonance19. The superradiant cavity couples with the subradiant cavity through the evanescent field of SPs.

(a) The schematic of the plasmonic sensor. (b) Theoretical transmission spectra for single cavity coupled system and combined system. Parameters for the Fano type curve (blue solid) are: ω0 = 2.29 × 1015 rad/s, Qc = 520, Qw = 13.5, Qi = 303, C = 0.998 and ψ = 3.9 rad. For the green dash curve are: ω0 = 2.33 × 1015 rad/s, Qw = 753.6, Qc = ∞. For the blue dash curve are: ω0 = 2.29 × 1015 rad/s, Qw = 13.5, Qc = ∞.

When the dielectric environment with refractive index n is filled in the entire system, the transmission coefficient at frequency ω can be derived by the coupled mode theory22,23 as

where ω0 is the resonant frequency of cavity 2, φ = 2πRe(neff)L1/λ + ψ is the phase shift for a half roundtrip in cavity 1, C is the related attenuation coefficient and ψ is the additional end-reflection phase shift in cavity 1. The effective refractive index neff in a MDM waveguide with width w can be obtained by solving the dispersion relation24. Qi, Qw, Qc are the quality factors those represent the internal decay ki, the coupling decay to the waveguide kw and to cavity 1 kc, respectively.

Figure 1(b) is the typical spectrum of a Fano resonance from equation (1). The wide blue dash curve is the transmission spectrum of the single lower cavity coupled system, while the narrow green dash curve is for the coupling waveguide system with a single upper cavity. Their coherent superposition leads to the asymmetric Fano lineshape, which is plotted as the solid blue curve. Figure 2(a) shows the 2D FDTD25 simulation results for structure with L1 = 546 nm, L2 = 530 nm, w = d = 50 nm, s = 20 nm and h = 60 nm. Two dips at 802.4 nm and 827.3 nm and the peak at 807.6 nm are marked as λ1, λ2 and λ3, respectively.

The optical features in Fig. 2(a) agree well with those in Fig. 1(b), which indicates that the physics mechanism of the Fano resonance can be best described by equation (1). For further investigation, here we define the asymmetry degree factor p of Fano line shape as p = (λ3 − λ1)/(λ2 − λ3). Figure 2(b) shows the transmission spectra for different p. Here p = 1 means a symmetric line shape as a special case, also known as the PIT effect24. As p increases from 0.36 to 2.76, the peak shifts to longer wavelength. Figure 2(c–e) are the related magnetic field distributions of transmission dips and peak wavelength in Fig. 2(a). We can see that at the Fano peak of 807.6 nm, the supperradiant mode is suppressed while excited for 802.4 and 827.3 nm.

Based on equation (1), when the system is surrounded by tested material with refractive index n + Δn, the transmission coefficient then can be derived as

where ω1 = ω0/(n + Δn), Qi′ and Qw′ are the resonance frequency and quality factors when the environment refractive index increases from n to n + Δn, while φ′ is the half roundtrip phase shift in cavity 1. Those values are obtained due to the approximation that the line shape of the optical response spectrum nearly maintains the same, only leading to a red-shift18,19.

It’s known that there are two common ways in describing the Figure of merit (FOM) of a sensor18,19,26,27. One is related to the intensity variation at a certain wavelength18,19 and the other relates to the shift and width of resonance peak26,27. By considering that the detection used in some sensors, plasmonic biosensor, for example, is usually made by measuring the light intensity variation for one particular wavelength, here we give a precise analytical expression for FOM at frequency ω for the proposed nanoplasmonic sensor as

where T(ω, n) and T(ω, n + Δn) have been obtained in equation (1) and (2), ΔT is the intensity variation at frequency ω caused by environment refractive index change Δn.

Discussions and Results

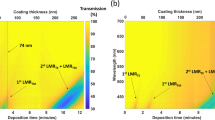

According to the standing wave condition of a Fabry-Perot cavity28, the resonance wavelength can be adjusted by the length and the width of the cavity, which finally determine the asymmetry degree factor p of a Fano system. Figure 3(a) is the dispersion relation between the neff and the wavelength in a MDM waveguide with various w. We can see that the neff for narrower w is larger than that for the wider one. Figure 3(b) shows the resonance wavelength as functions of cavity length L1 with different coupling distance s for single cavity coupled MDM waveguide system. It’s found that the numerical wavelengths are consistent with the theoretical ones, which ensures the precise adjustment of Fano resonance.

Since the Fano line shape can be precisely controlled, we now discuss the sensing performance of the proposed nanosensor. Here the parameters are those used in Fig. 2(a). In the following discussion, we only modify L1 while the others maintain the same. A typical sensing response can be found when the refractive index n of the environment increases from 1.000 to 1.015, shown as Fig. 4(a). By using equation (3), we get a FOM of ~2040 for dip 2 at 827.3 nm and 760 for dip 1 at 802.4 nm, which are much higher than that in18,19,29 and a sensitivity of 780 nm/RIU is also achieved. Those features can be beneficial for the sensing applications. The Fano spectrum in Fig. 4(a) is with an asymmetric factor p < 1, what will happen to the FOM if p gets enlarged? We first display the theoretical relations between the FOM and L1, shown in Fig. 4(b). It can be seen that as L1 increases from 532 nm to 580 nm, indicating an enlarging p, the FOM for dip 1 increases from 340 to 1948 accordingly. This is because the initial dip transmission T becomes smaller when L1 increases, seen in Fig. 2(b). In fact, the ΔT for dip 1 is also decreased due to the variational asymmetric degree of the line shape. Nevertheless, the total FOM for dip 1 still increases. Thus we can infer that the FOM for dip 1 is much more sensitive to the initial T rather than to the ΔT. For the sensing performance of dip 2, the FOM shows a nonmonotonic change. The FOM starts from 1978 and reaches a maximum of 2569 when L1 = 562 nm. But then drops down as L1 keeps on increasing. This interesting phenomenon can be explained by T and ΔT from the FOM definition. As L1 increases, the Fano peak shifts to longer wavelength. That will make both the ΔT and the initial T at dip 2 increase. Thus there seems to be a competition between those two factors and the numerator ΔT plays the dominant role in tuning the FOM at the beginning. As L1 keeps increasing, this competition reaches a balance at L1 = 562 nm, leading to a maximum FOM of 2569. When L1 gets larger, the situation reversed. The denominator T turns to play the key role in adjusting the FOM. We conclude that for adjusting the FOM at dip 2, the competition between ΔT and T determines the FOM. For small L1, the intensity variation ΔT plays the key role, while for large L1, the initial T takes charge of it. Another interesting finding is that there is a cross point when L1 = 568 nm, this means two equal sensing peaks can be obtained by suitably choosing the cavity length. Thus this simple nanosensor also has potential applications as a double functional sensor, which is extremely sensitive to more than one wavelength (or frequency). To support those theoretical analysis and prediction, we provide the corresponding numerical results by FDTD simulations. The numerical relation between the FOM and L1 is shown in Fig. 4(c) and a highest FOM of ~4800 is achieved for L1 = 556 nm. We find that the tendency and law revealed in the numerical results agree well with those in the theoretical ones, which means the adjustment and evolution of FOM can be appropriately depicted by equation (3). The only difference between these two groups of result is the magnitude. The overall numerical FOMs are larger than the theoretical ones due to the relatively lower initial intensity T from the simulation. The relation between the wavelength where the FOM reaches its maximum and cavity length L1 is also discussed theoretically and numerically, shown in Fig. 4(d,e), respectively. The consistency of these two figures reveals that the location of the sensing peaks can be accurately predicted, which is beneficial for the sensor design. Here the solid curves in Fig. 4(b–e) are the B-spline fit to the data points. As we know, for subwavelength plasmonic sensing application, the very small volume that can be interrogated is also quite important. In the above discussion, we mainly focus on the dielectric environment change of the whole structure, including both the bus waveguide and the cavities. We now investigate the situation that the dielectric change only happens to some of the components (waveguide and cavities) of the nanoplasmonic sensor. Here we still consider the sensor in Fig. 2(a) and the cases of changing dielectric in cavity1 only, cavity 2 only and the waveguide only are briefly discussed, respectively. The corresponding FOM for the left (right) sensing peak are obtained as 695(634), 541(1770) and 5(35) for the above three types, which are smaller than 1676(2946) for the regular case, observed in Fig. 4(c). It is worth to note that, the extremely low FOM for the third group results from the fact that the spectrum showing relatively low sensitivity to the dielectric change in the bus waveguide. In addition, we also study the refractive index change in more than one component, such as cavity 1 and 2, cavity 1 and the waveguide, cavity 2 and the waveguide, respectively. And the corresponding FOM for the left (right) sensing peak are obtained as 1826(3263), 587(520) and 453(1522). Here the FOM for the first situation of 1826(3263) is close to 1676(2946) for the regular case and the slight improvement may attribute to the decreased loss in the bus waveguide. These findings indicate that the sensing property can also be regulated by properly choosing the area where the sensing is actually taking place.

In the above section, we discuss the universal sensing based on Fano resonance in a cavity coupled MDM waveguide system and find the way to accurately adjust the sensing property. Since the Fano resonance is the interference effect between the superadiant mode and the subradiant mode, the phase dispersion can be formed in a certain wavelength range and leads to a slow-light effect, shown in Fig. 5(a). The blue dots in the phase shift curve represent the locations of the maximum group index. The decrease of group velocity can enhance the light intensity by the pulse compression13, which will give rise to good sensing performance. Now we study the slow-light sensing in our Fano based sensor15. First we give the group index of this sensor system as Ng = c/vg = (c/H) · τg = (c/H) · (dθ(ω)/dω)30, where vg is the group velocity, τg is delay time and the phase shift θ(ω) is the function of angular frequency ω, H = 1000 nm is the length of the plasmonic system. Figure 5(b) depicts the group index of a sensor with L1 = 556 nm for various n. For n = 1, dielectric as air, the group index reaches its maximum of ~20 at 822.4 nm for the transmission peak. Due to the fact that the maximum FOM of a sensor appears at the dip wavelength, we pay more attention to the group index variation at the two dips 811.8 and 832.8 nm. When n = 1.005, the group index of pulse at 832.8 nm reaches to 2, seen as the green crosspoint between the red curve and the black horizontal dash line, which means the group velocity can be halved and results in an enhanced intensity. When n = 1.012, the group index reaches the maximum. The inset of Fig. 5(b) is the group index for pulse at 832.8 nm with different n, which increases first and then drops.

While for wavelength of 811.8 nm, the group index nearly maintains the same when n increase. Briefly, the group index for wavelength at dip 1 is not sensitive to the environment, which means only a universal sensing here, just like the discussion in the former section. However, for wavelength at 832.8 nm, its group velocity is quite sensitive to the surrounding dielectric. If we consider Ng ≥ 2 as slow-light region, an optical pulse with specific wavelength will be slowed down in the sensor within a certain range of n. We define a sensing width with slow-light (SWS) as:  to characterize this certain range.

to characterize this certain range.  and

and  represent to the refractive index of dielectric environment for Ng reaching its maximum and 2, respectively.

represent to the refractive index of dielectric environment for Ng reaching its maximum and 2, respectively.

For some particular wavelength, its pulse intensity can be enhanced during the sensing process. We also give this slow-light sensing an analytical expression based on the discussion in31. By utilizing the condition that Ng = c/vg, it can be further derived as

Here FOMS(ω) is the sensitivity of slow-light sensing, Δn is chosen to be the SWS. Thus Ng(ω, n + Δn) is the maximum group index and Ng(ω, n) equals 2. We show the relation between the FOMS and the SWS for different Fano asymmetric degree factor p. In Fig. 5(c), for p < 1, a tradeoff exists and a maximum FOMS of ~1131 is achieved when L1 = 556 nm, while the SWS reaches its highest value of 0.031 when L1 = 536 nm. This contradictory relation can be explained from equation (4). As L1 getting closer to 556 nm, the Fano line shape becomes more symmetric and the group index of the work wavelength increases and reaches its maximum of 20 when L1 = 556 nm. At the meantime, the SWS gets smaller since the slow-light band for dip 2 gets narrower. Thus for L1 = 556 nm, the highest group index while the narrowest SWS are obtained, which lead to a maximum FOMS. So the asymmetric degree factor p can also affect the slow light sensing and we can get high slow-light sensitivity by making a symmetric line shape. Will the value of 1131 be the highest? And is the tendency reveals in Fig. 5(c) still suitable for larger p? The FOMS and the SWS as functions for L1 > 556 nm (p > 1) are shown in Fig. 5(d). At the beginning, the FOMS increases rather than decreases. Because both the Ng and the SWS become small, but the decreasing rate of SWS is faster than that of Ng, thus leading to the increased slow-light sensitivity by equation (4). However, this increase trend stops and reaches a maximum of 3750 at L1 = 572 nm, this is probably a balance that the decreasing rate of the SWS is equal to that of the Ng. After that, the SWS decreases slowly while the Ng decreases relatively fast, thus the FOMS finally goes down. We can conclude that there is a tradeoff between the FOMS and the SWS. Higher FOMS usually results in lower SWS, which is also revealed in23. However, for real application, we need to make both of them large enough. Now we devote to make the SWS (FOMS) large enough without sacrificing the FOMS (SWS). Fortunately, this contradiction can be overcome. Based on the qualitative analysis from equation (4), in order to make the SWS large enough without sacrificing the FOMS, this problem can be resolved by appropriately increase the Ng and the SWS of the Fano-based plasmonic sensor. These can be realized by adjusting the quality factor Qt of the superradiant mode and the asymmetric degree p of the Fano line shape, which can increase the Ng and the SWS, respectively. Figure 6(a) shows the SWS and the FOMS as functions of L1 for various quality factors Qt. Here the parameter Qts are chosen as 6, 7, 8.5, 10 and 13.5 from left to right in the horizontal axis. As we properly decrease Qt and L1, the SWS can be enlarged from 0.008 to 0.013 with a nearly unchanged FOMS of 1127, which verifies the assumption in the former discussion. For the second problem, the solution can be simpler. We only need to decrease the quality factor Qt, which almost keeps the width of the slow-light band but increases the group index. By doing this we get an increasing FOMS but nearly constant SWS. Here we deduce that the contradiction may also be resolved by approximately choosing the coupling distance h and consumption in system due to the fact that these two factors can also affect the SWS and the Ng. The revealed contradiction relation between SWS and the FOMS and the solutions may have potential applications in fundamental research and design of slow-light sensor.

Conclusions

In conclusion, both the universal and the slow-light sensing can be achieved in a plasmonic MDM waveguide sensor based on Fano resonance. The consistency between the theoretical prediction and the numerical results in sensing property adjustment can be helpful in the sensor design and application. The Fano asymmetric factor p plays important role in adjusting both the universal and the slow-light sensing characteristic. The contradiction in slow-light sensing can be overcome by suitably tuning the loss of the superradiant mode and the Fano asymmetric factor p. The presented analysis and features of this simple plasmonic sensor can be useful in integrated compact plasmonic devices.

Methods

The optical property of the silver nanostructure is approximated by the Drude model: ε(ω) = ε∞ − ωp2/(ω2 + iωγp), with ωp = 1.38 × 1016 s−1 is the bulk plasmon frequency, ε∞ = 3.7 and γp = 2.73 × 1013 s−1 represents the damping rate. The characteristic spectral responses of the structures are found by using the two-dimensional FDTD method with grid size Δx = Δy = 2.5 nm, S and P represent the incident and the detected plane, respectively. The calculation domain is surrounded by perfectly matched layer absorbing boundary. We choose FDTD solutions as our simulation software. And the simulation parameters have been given in our paper.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Zhan, S. et al. Tunable nanoplasmonic sensor based on the asymmetric degree of Fano resonance in MDM waveguide. Sci. Rep. 6, 22428; doi: 10.1038/srep22428 (2016).

References

Gramotnev, D. & Bozhevolnyi, S. Plasmonics beyond the diffraction limit. Nat. Photonics 4, 83–91 (2010).

Ozbay, E. Plasmonics: Merging photonics and electronics at nanoscale dimensions. Science 311, 189–193 (2006).

Miroshnichenko, E., Flach, S. & Kivshar, S. Fano resonances in nanoscale structures. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 2257 (2010).

Anker, J. et al. Biosensing with plasmonic nanosensors”, Nat. Mater. 7, 442–453 (2008).

Piao, X., Yu, S. & Park, N. Control of Fano asymmetry in plasmon induced transparency and its application to plasmonic waveguide modulator. Opt. Express 20, 18994–18999 (2012).

Bao, K., Mirin, N. & Nordlander, P. Fano resonances in planar silver nanosphere clusters. Appl. Phys. A 100, 333 (2010).

Liu, N. et al. Planar metamaterial analogue of Electromagnetically Induced Transparency for plasmonic sensing. Nano Lett. 10, 1103–1107 (2010).

Hao, F. et al. Symmetry breaking in plasmonic nanocavities: Subradiant LSPR sensing and a tunable Fano resonance. Nano Lett. 8, 3983–3988 (2008).

Lee, K. et al. Enhancing surface plasmon detection using template-stripped gold nanoslit arrays on plastic films. ACS Nano 6(4), 2931–2939 (2012).

Fu, Y., Zhang, J., Yu, Y. & Luk’yanchuk, B. Generating and manipulating higher order Fano resonances in dual-disk ring plasmonic nanostructures. ACS Nano 6(6), 5130–5137 (2012).

Luk’yanchuk, B. et al. The Fano resonance in plasmonic nanostructures and metamaterials. Nat. Mater. 9, 707–715 (2010).

Li, Z. et al. Fano resonances in THz metamaterials composed of continuous metallic wires and split ring resonators”, Opt. Express 22, 26572–26584(2014).

Krauss, T. Slow light in photonic crystal waveguides. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 40, 2666 (2007).

Huang, Y., Min, C., Dastmalchi, P. & Veronis, G. Slow-light enhanced subwavelength plasmonic waveguide refractive index sensors. Opt. Express 23, 14922–14936 (2015).

Wen, H., Terrel, M., Fan, S. & Digonnet, M. Sensing with slow light in fiber Bragg gratings. IEEE Sens. J. 12, 156–163 (2012).

He, Z. et al. Tunable multi-switching in plasmonic waveguide with Kerr nonlinear resonator. Sci. Rep. 5, 15837 (2015).

He, Z. et al. Oscillator Model Analysis for Slow Light in Bright-Dark-Dark Waveguide Systems. IEEE Photonic. Tech. L. 27, 2371–2374. (2015).

Qi, J. et al. Independently tunable double Fano resonances in asymmetric MIM waveguide structure. Opt. Express 22, 14688–14695 (2014).

Lu, H., Liu, X., Mao, D. & Wang, G. Plasmonic nanosensor based on Fano resonance in waveguide-coupled resonators. Opt. Lett. 37, 3780–3782 (2012).

Wu, T. et al. The sensing characteristics of plasmonic waveguide with a ring resonator. Opt. Express 22, 7669–7677 (2014).

Zafar, R. & Salim, M. Enhanced figure of merit in Fano resonance-based plasmonic refractive index sensor. IEEE Sens. J. 15, 6313–6317 (2015).

Yariv, A. Coupled-mode theory for guided-wave optics. IEEE J. Quantum Elect. QE-9, 919 (1973).

Zhan, S. et al. Sensing analysis based on plasmon induced transparency in nanocavity-coupled waveguide. Opt. Express 23, 20313–20320 (2015).

Lu, H., Liu, X. & Mao, D. Plasmonic analog of electromagnetically induced transparency in multi-nanoresonator-coupled waveguide systems. Phys. Rev. A 85, 053803 (2012).

Taflove, A. & Hagness, S. Computational Electrodynamics: The Finite-Difference Time-Domain Method, 3rd ed, Artech, House, Boston, (2005).

Ameling, R. et al. Cavity-enhanced localized plasmon resonance sensing. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 253116 (2010).

Wang, J. et al. Double Fano resonances due to interplay of electric and magnetic plasmon modes in planar plasmonic structure with high sensing sensitivity. Opt. Express 21, 2236–2244 (2013).

Zhang, Q., Huang, X., Lin, X., Tao, J. & Jin, X. A subwavelength coupler-type MIM optical filter. Opt. Express 17, 7549 (2009).

Liu, N., Mesch, M., Weiss, T., Hentschel, M. & Giessen, H. Infrared perfect absorber and its application as plasmonic sensor. Nano Lett. 10, 2342–2348 (2010).

Zhan, S. et al. Slow light based on plasmon-induced transparency in dual-ring resonator-coupled MDM waveguide system. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 47, 205101 (2014).

Povinelli, M., Johnson, S. & Joannopoulos, J. Slow-light, band-edge waveguides for tunable time delays. Opt. Express 13, 7145–7159 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China under Grant No. 20100162110068 and the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 61275174.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This research was planned by S.Z., Y.P. and H.L. S.Z. developed the analytic theory. Numberical simulation was performed by S.Z., Z.H. and B.L. The authors S.Z., Y.P., Z.H., B.L., Z.C. and H.L. discussed the results. S.Z. and H.X. wrote the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Zhan, S., Peng, Y., He, Z. et al. Tunable nanoplasmonic sensor based on the asymmetric degree of Fano resonance in MDM waveguide. Sci Rep 6, 22428 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep22428

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep22428

This article is cited by

-

Realizing multiple Fano resonance in an end-coupled semi-ring resonator-coupled waveguide structure

Journal of Optics (2023)

-

A Voyage from Plasmonic to Hybrid Waveguide Refractive Index Sensors Based on Wavelength Interrogation Technique: a Review

Brazilian Journal of Physics (2022)

-

Optical properties of MIM plasmonic waveguide with an elliptical cavity resonator

Applied Physics A (2020)

-

Review on plasmon induced transparency based on metal-dielectric-metal waveguides

Journal of Central South University (2020)

-

Dynamically tunable switch and filter in single slot cavity structure

Scientific Reports (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.