Abstract

We clarify the nature of dynamic coupling in plasmonic resonators and determine the dynamic coupling coefficient using a simple analytic model. We show that plasmonic resonators, such as subwavelength holes in a metal film which can be treated as bound charge oscillators, couple to each other through the retarded interaction of oscillating screened charges. Our dynamic coupling model offers, for the first time, a quantitative analytic description of the fundamental symmetric and anti-symmetric modes of coupled resonators which agrees with experimental results. Our model also reveals that plasmonic electromagnetically induced transparency arises in any coupled resonators of slightly unequal lengths, as confirmed by a rigorous numerical calculation and experiments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plasmonic nano resonators formed by various metallic nanostructures are at the core of plasmonics and metamaterial researches. Novel features arise when resonators are coupled to each other, including cases such as plasmonic dimers1,2,3, plasmon induced transparency4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11, directional optical antenna12,13,14 and high refractive index metamaterials15,16. The interaction of localized plasmons in nanoparticle dimers has been explained in terms of a simple dipolar interaction17 or plasmon hybridization1,18, the more general method. Though these approaches provide a reasonable description of coupled nanoparticles, they fail to accommodate the dynamical behaviour of coupled plasmonic resonators with accurate quantitative predictions, one of the most important open questions in plasmonics and metamaterial research. Recently, a single plasmonic resonator has been rigorously identified as a radiating dipole oscillator19,20. A plasmonic resonator, for instance a half-wavelength rectangular hole in a metal film, can be identified as a bound charge oscillator, and, accordingly, the scattering of light by a resonator can be quantitatively described in terms of the scattering spectrum of a bound charge oscillator20,21. This realisation raises the possibility of rigorously describing the interaction between plasmonic resonators in terms of bound charge oscillators.

In this Letter, we clarify the nature of dynamic coupling in plasmonic resonators by showing that plasmonic resonators couple to each other through the retarded interaction of bound charge oscillators. We determine the dynamic coupling of resonators explicitly from their retarded interaction and screened charges, allowing us to develop quantitative descriptions of the fundamental symmetric and anti-symmetric modes of coupled resonators in good agreement with actual experiments and exact numerical results. Importantly, our dynamically coupled oscillator model predicts the presence of the plasmonic electromagnetically induced transparency (EIT) in any coupled resonators of unequal lengths. Our model provides an analytic and for the first time quantitative description of EIT in plasmonic resonators. We show that the EIT of coupled oscillators arises from the destructive interference of two fundamental modes with distinct phase properties and that, as we confirm experimentally, the same feature arises in coupled plasmonic resonators. Our dynamic coupling approach is not restricted to the rectangular hole-type resonators considered in this paper. It can be readily applied to interacting plasmonic resonators in general and various building blocks of metamaterials.

Results

Oscillator picture of coupled resonators

We first recall that a single plasmonic resonator can be identified as a radiating bound charge dipole oscillator20. Consider for example a narrow rectangular hole of size a × b in a thin metal film. When light is incident upon the rectangular hole with a polarization perpendicular to its long side, the total cross section of the free standing rectangular hole is given by the normalized energy flow through it,

where c is the speed of light,  is the angular frequency of the incident wave and

is the angular frequency of the incident wave and  . T is the dispersive time parameter,

. T is the dispersive time parameter,

with the Euler’s constant  . It was noted that a similar scattering property arises in a bound charge oscillator obeying the equation of motion,

. It was noted that a similar scattering property arises in a bound charge oscillator obeying the equation of motion,

where x(t) is the displacement from the equilibrium position of a particle of mass m and charge q. Terms in the right side of Eq. (3) represent the restoring force, the radiative reaction force and the external force, respectively. The radiative reaction force, also known as the Abraham-Lorentz force, is responsible for the radiative energy loss characterized by the time constant  . The total cross section of a bound charge oscillator

. The total cross section of a bound charge oscillator  is defined as the ratio of the time-averaged radiated power to the incident intensity. Using the Larmor formula,

is defined as the ratio of the time-averaged radiated power to the incident intensity. Using the Larmor formula,  , we find

, we find

Comparing Eqs. (1) and (4) reveals that the scattering cross section is identical, after allowing for the 50% reduction in intensity for the slot case which represents only forward scattering. If we choose  , or equivalently introduce a dispersive oscillator mass,

, or equivalently introduce a dispersive oscillator mass,

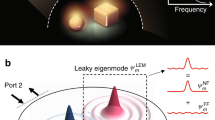

Now, we consider two interacting plasmonic resonators, two rectangular holes of dimensions  and

and  separated by distance d as shown in Fig. 1a. Light is incident upon the holes with a polarization perpendicular to the long sides of the rectangles. The oscillator model of a plasmonic resonator suggests that an interaction between resonators can be treated as if it were an interaction between oscillating bound charges and we show that this is indeed the case. Since rectangular holes are complementary structures to rod type resonators, Babinet’s principle indicates that the corresponding charged oscillators can be restricted to movement along the x-direction with displacements

separated by distance d as shown in Fig. 1a. Light is incident upon the holes with a polarization perpendicular to the long sides of the rectangles. The oscillator model of a plasmonic resonator suggests that an interaction between resonators can be treated as if it were an interaction between oscillating bound charges and we show that this is indeed the case. Since rectangular holes are complementary structures to rod type resonators, Babinet’s principle indicates that the corresponding charged oscillators can be restricted to movement along the x-direction with displacements  and

and  as shown in Fig. 1b. The equations of motion for coupled oscillators are

as shown in Fig. 1b. The equations of motion for coupled oscillators are

(a) Coupled slot resonators made of two rectangular holes of dimensions  and

and  separated by distance

separated by distance  in a perfect electric conductor (PEC) of negligible thickness. Light is incident normally upon the rectangular hole with a polarization perpendicular to its long side. (b) Bound charge oscillator model corresponding to coupled slot resonators. Bound charges, separated by distance

in a perfect electric conductor (PEC) of negligible thickness. Light is incident normally upon the rectangular hole with a polarization perpendicular to its long side. (b) Bound charge oscillator model corresponding to coupled slot resonators. Bound charges, separated by distance  at rest, oscillate along the x-direction only. (c) Dynamic coupling constant

at rest, oscillate along the x-direction only. (c) Dynamic coupling constant  against charge separation.

against charge separation.

where  and a phase difference

and a phase difference  is allowed between the externally applied forces. The term

is allowed between the externally applied forces. The term  is the x-component of the Lorentz force F21 acting on q1 and likewise for

is the x-component of the Lorentz force F21 acting on q1 and likewise for  with 1↔2,

with 1↔2,

We include the effect of charge screening on the interaction of plasmonic resonators using a screened charge  with a screening factor S which will be determined later. E21 and B21 are the electric and magnetic fields due to charge q2 measured at the retarded time t–r/c,

with a screening factor S which will be determined later. E21 and B21 are the electric and magnetic fields due to charge q2 measured at the retarded time t–r/c,

where  with unit vector

with unit vector  and r1 and r2 are the position vectors of the charges q1 and q2 respectively. We assume that displacements x1(t) and x2(t) are much smaller than separation d so that

and r1 and r2 are the position vectors of the charges q1 and q2 respectively. We assume that displacements x1(t) and x2(t) are much smaller than separation d so that  . This, together with the harmonic time dependence of x2 with a factor

. This, together with the harmonic time dependence of x2 with a factor  , simplifies

, simplifies  to yield

to yield

with the dynamic coupling coefficient

The time-averaged power provided by the external field to charge  is

is

with the equivalent expression for power P2 and charge q2 also holding. Then the total cross section  of the coupled oscillator, defined as the ratio of the total power P1 + P2 to the incident intensity, becomes

of the coupled oscillator, defined as the ratio of the total power P1 + P2 to the incident intensity, becomes

Determination of dynamic coupling

For a better understanding of coupling and charge screening, we consider the case of two identical oscillators with  and

and  . Coupled identical oscillators admit two fundamental modes, symmetric and anti-symmetric. The symmetric mode is driven by external fields without a phase difference (

. Coupled identical oscillators admit two fundamental modes, symmetric and anti-symmetric. The symmetric mode is driven by external fields without a phase difference ( ) and is characterized by the steady state solution (see Supplementary Information for detailed derivation of Eq (13)–(17))

) and is characterized by the steady state solution (see Supplementary Information for detailed derivation of Eq (13)–(17))

The corresponding total cross section becomes

Similarly, the anti-symmetric mode is driven by external fields of phase difference  and given by

and given by

so that the corresponding total cross section becomes

Here,  are the real(imaginary) part of the coupling coefficient

are the real(imaginary) part of the coupling coefficient  in Eq. (10) which without the factor S2 becomes singular as the separation r0 between the two charges becomes zero. In the case of coupled plasmonic resonators of identical dimensions a × b, as the separation between the two rectangular holes becomes zero, they merge into a single rectangular hole of size a × 2b. Since the scattering cross section in (4), evaluated near the resonance

in Eq. (10) which without the factor S2 becomes singular as the separation r0 between the two charges becomes zero. In the case of coupled plasmonic resonators of identical dimensions a × b, as the separation between the two rectangular holes becomes zero, they merge into a single rectangular hole of size a × 2b. Since the scattering cross section in (4), evaluated near the resonance  , is independent of the short side b, at the limit of zero separation we would expect the total scattering cross section of coupled identical resonators to reduce to that of a single resonator. It can be readily shown that this requirement is fulfilled with the choice of the screening factor S = S0 where

, is independent of the short side b, at the limit of zero separation we would expect the total scattering cross section of coupled identical resonators to reduce to that of a single resonator. It can be readily shown that this requirement is fulfilled with the choice of the screening factor S = S0 where

Finally, fixing the dynamic coupling coefficient in (10) with S = S0 as shown in Fig. 1c, we establish the oscillator model for dynamically coupled resonators.

To confirm the validity of our model, we compare the total cross sections of coupled oscillators with numerically-calculated and experimentally-measured cross sections of corresponding coupled resonators. The results are shown in Fig. 2 in which the spectrum of the scattering cross section in symmetric mode given by (14) is plotted against resonator separation (the antisymmetric case is given in Supplementary Fig.S1). The scattering cross section is normalized by maximum value of the cross section from single resonator shown in Eq.(4). In Fig. 2b, the vertical breaks in the oscillator scattering cross section represent scattering spectra at the maximum scattering separation. The horizontal break shown in Fig. 2c at λ = λ0 = 2a (the black solid line) indicates that the cross section varies from 1 to 3 and converges to 2 in an oscillatory manner as the separation distance increases. This is in accordance with the expectation that the effect of coupling diminishes with larger separations. The positions of the spectral peaks in Fig. 2d show both blue and red shifts from the single resonator resonance, λ = λ0 = 2a, depending on the degree of separation of the coupled resonators. Remarkably, all these properties predicted by the oscillator model turn out to be in excellent agreement with not only the scattering behaviour of coupled resonators calculated using a rigorous FDTD numerical method but also the experimental data from microwave measurement.

(a) Scattering cross section of the oscillator model in symmetric mode plotted against incident wavelength and charge separation. Scattering cross section is normalized by that of single resonator at the resonance, and wavelength and separation are in the unit of the long side of the rectangle  . (b) Vertical breaks of (a) from the oscillator model (thick line) in comparison with the experiment (thin line), and the FDTD calculation (square dot). Separations between oscillators are 1.3a. (c) Horizontal break of (a) at resonance wavelength (black line) in comparison with the experiment (red dot), and the FDTD calculation (square dot). (d) Resonance peak shifts of the cross section in symmetric mode.

. (b) Vertical breaks of (a) from the oscillator model (thick line) in comparison with the experiment (thin line), and the FDTD calculation (square dot). Separations between oscillators are 1.3a. (c) Horizontal break of (a) at resonance wavelength (black line) in comparison with the experiment (red dot), and the FDTD calculation (square dot). (d) Resonance peak shifts of the cross section in symmetric mode.

Plasmonic EIT in asymmetric resonators

One of the most intensively studied properties of coupled resonators is the plasmonic analogue of electromagnetically induced transparency (EIT) which arises from the interference between bright (symmetric) and dark (anti-symmetric) modes. Various coupled resonator systems such as the dipole-quadrupole antenna pair10,11 have been employed to demonstrate EIT but without analytic quantitative predictions. Here, we show that a simple system of two parallel rectangular holes of unequal size indeed leads to EIT by opening a dip in the scattering cross section. Our oscillator model approach presents an analytic expression for the scattering cross section which also shows reasonable quantitative agreement with experimental results. Consider the two non-identical rectangular holes specified in Fig. 1 where the aspect ratio  is close to one. The steady state solution of the corresponding oscillator equation is given by (see Supplementary Information for derivation)

is close to one. The steady state solution of the corresponding oscillator equation is given by (see Supplementary Information for derivation)

The total scattering cross section is readily obtained from Eq. (12). In order to see the EIT behaviour explicitly, we note that the coupling constant can be approximated to  if the separation of the rectangular holes is small. Then, the total scattering cross section simplifies to

if the separation of the rectangular holes is small. Then, the total scattering cross section simplifies to

Note that  possesses zero,

possesses zero,  , at

, at

where we approximated  as

as  . This causes a dip in the broad resonance peak as shown in Fig. 3. Figure 3a shows the cross section spectrum in (19) while Fig. 3b,c show respectively the experimental and the FDTD numerical results for the scattering cross section of two rectangular holes corresponding to four different aspect ratios. Despite the simplicity, our oscillator model prediction manifesting EIT behaviour shows remarkable agreement with both the experimental and rigorous numerical results. Figure 3d compares the dip position predictions of the oscillator model with numerical and experimental results and once again the agreement is good since it is within 2 percent. Figure 4 describes the distinct spectral phase properties of EIT. We compared the phase differences between two oscillators with those between coupled resonators. To show phase difference between slots, we measure near-field of each slot using hairpin antenna. The

. This causes a dip in the broad resonance peak as shown in Fig. 3. Figure 3a shows the cross section spectrum in (19) while Fig. 3b,c show respectively the experimental and the FDTD numerical results for the scattering cross section of two rectangular holes corresponding to four different aspect ratios. Despite the simplicity, our oscillator model prediction manifesting EIT behaviour shows remarkable agreement with both the experimental and rigorous numerical results. Figure 3d compares the dip position predictions of the oscillator model with numerical and experimental results and once again the agreement is good since it is within 2 percent. Figure 4 describes the distinct spectral phase properties of EIT. We compared the phase differences between two oscillators with those between coupled resonators. To show phase difference between slots, we measure near-field of each slot using hairpin antenna. The  -field component has been measured near the edge of slots. The fields resonantly excited inside each of the rectangular holes correspond to the first and the second peaks in Fig. 4b,d. Around the transmission dip, both holes are excited and a

-field component has been measured near the edge of slots. The fields resonantly excited inside each of the rectangular holes correspond to the first and the second peaks in Fig. 4b,d. Around the transmission dip, both holes are excited and a  -phase difference is expected to arise due to the resonant excitation of a dark mode as shown in Fig 4c,a confirms that this is indeed the case.

-phase difference is expected to arise due to the resonant excitation of a dark mode as shown in Fig 4c,a confirms that this is indeed the case.

Systems consist of two non-identical rectangular holes of dimensions  and

and  where the aspect ratio

where the aspect ratio  is chosen specifically with values

is chosen specifically with values  =1.1 (black), 1.2 (red), 1.3 (blue), and 1.4 (green) and

=1.1 (black), 1.2 (red), 1.3 (blue), and 1.4 (green) and  . (a) Scattering cross section spectra of corresponding oscillator models obtained from Eq. (19). (b) Microwave measurement of scattering cross sections of coupled resonators and (c) the FDTD numerical results. Scattering cross section is normalized by the cross section of resonant (

. (a) Scattering cross section spectra of corresponding oscillator models obtained from Eq. (19). (b) Microwave measurement of scattering cross sections of coupled resonators and (c) the FDTD numerical results. Scattering cross section is normalized by the cross section of resonant ( ) single oscillator of dimension

) single oscillator of dimension  at the resonance, and wavelength is in the unit of

at the resonance, and wavelength is in the unit of  . (d) Spectral dip positions against the aspect ratio obtained from the oscillator model (black line), the experiment (red circle), and the FDTD calculation (blue square).

. (d) Spectral dip positions against the aspect ratio obtained from the oscillator model (black line), the experiment (red circle), and the FDTD calculation (blue square).

(a) Spectral phase differences in coupled resonators possessing the aspect ratio  and in the corresponding oscillator. The phase difference of the

and in the corresponding oscillator. The phase difference of the  -field component has been measured at the center of the two slots separated by distance

-field component has been measured at the center of the two slots separated by distance  using a hairpin antenna (thin curve). This is compared with the FDTD result (square dot) and the phase difference in two bound charge oscillators (thick curve). (b–d)

using a hairpin antenna (thin curve). This is compared with the FDTD result (square dot) and the phase difference in two bound charge oscillators (thick curve). (b–d)  field maps obtained by the FDTD calculation showing the excitation of the dark mode of EIT. Modes at (b) the first peak, (c) the dip and (d) the second peak of EIT spectrum.

field maps obtained by the FDTD calculation showing the excitation of the dark mode of EIT. Modes at (b) the first peak, (c) the dip and (d) the second peak of EIT spectrum.

Discussion

In conclusion, we have successfully described the behaviour of interacting plasmonic resonators with a coupled oscillator model which has been derived analytically from the full diffraction theory. The dynamic coupling coefficient of the oscillator model has been determined by the retarded interaction between oscillating screened charges. The oscillator model allowed quantitative predictions about interacting resonators, particularly their EIT behaviour, which agreed with both numerical and experimental results. Our oscillator model approach is not restricted to rectangular-holed plasmonic resonators but can be readily applied to other types of plasmonic resonator such as rod-type nano antennae. Features of the bound charge oscillator model such as radiative damping, retarded interaction, and screening effects are also shared by coupled plasmonic resonators. This suggests that the dynamic coupling approach presented in this paper provides a general analytic framework for coupled resonators.

Methods

Microwave measurements have been performed using the experimental setup in Fig. 5. Slots are perforated on a stainless steel, which exhibits a nearly ideal metal behavior at micro-frequency of 2.6–3.9 GHz. A Hewlett-Packard 8719C network analyzer and a SGH260 standard gain horn antenna were used to generate the y-polarized electric field. To reduce the background noise, we surrounded the experimental setup using KSS-12 pyramidal absorbers. To measure the far and near components of electric field, we used a rod antenna made of a LMR-400 coaxial cable, and a hairpin antenna made of a RG-405 coaxial cable. Since the forward scattering amplitude is proportional to the total cross section according to the optical theorem, we have measured the forward scattering amplitude from a double slot and normalized it by the maximum value of the forward scattering amplitude from a single slot. To measure the phase difference between slots, we measured the near field component, using the hairpin antenna, near the edge of a slot in order not to disturb the field distribution.

We made numerical calculations using the FDTD (finite-difference time-domain) method where metal is assumed to be a perfect conductor which is valid in the microwave region. The grid size of the FDTD calculation was  .

.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Lee, S. and Park, Q.-H. Dynamic coupling of plasmonic resonators. Sci. Rep. 6, 21989; doi: 10.1038/srep21989 (2016).

References

Nordlander, P., Oubre, C., Prodan, E., Li, K. & Stockman, M. I. Plasmon Hybridization in Nanoparticle Dimers. Nano Lett. 4, 899–903 (2004).

Aćimović, S. S., Kreuzer, M. P., González, M. U. & Quidant, R. Plasmon near-field coupling in metal dimers as a step toward single-molecule sensing. ACS Nano 3, 1231–1237 (2009).

Olk, P., Renger, J., Wenzel, M. T. & Eng, L. M. Distance dependent spectral tuning of two coupled metal nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 8, 1174–8 (2008).

Liu, N. et al. Planar Metamaterial Analogue of Electromagnetically Induced Transparency for Plasmonic Sensing. Nano Lett. 10, 1103–7 (2010).

Artar, A., Yanik, A. a. & Altug, H. Multispectral plasmon induced transparency in coupled meta-atoms. Nano Lett. 11, 1685–9 (2011).

Papasimakis, N. et al. Metamaterial with polarization and direction insensitive resonant transmission response mimicking electromagnetically induced transparency. Appl. Phys. Lett. 94, 211902 (2009).

Duan, X. et al. Polarization-insensitive and wide-angle plasmonically induced transparency by planar metamaterials. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 143105 (2012).

Ye, Z. et al. Mapping the near-field dynamics in plasmon-induced transparency. Phys. Rev. B 86, 155148 (2012).

Taubert, R., Hentschel, M., Kästel, J. & Giessen, H. Classical analog of electromagnetically induced absorption in plasmonics. Nano Lett. 12, 1367–71 (2012).

Liu, N. et al. Plasmonic analogue of electromagnetically induced transparency at the Drude damping limit. Nat. Mater. 8, 758–62 (2009).

Zhang, S., Genov, D. a., Wang, Y., Liu, M. & Zhang, X. Plasmon-Induced Transparency in Metamaterials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 047401 (2008).

Simba, A. Y., Yamamoto, M., Nojima, T. & Itoh, K. Planar-type sectored antenna based on slot Yagi–Uda array. IEE Proc. - Microwaves, Antennas Propag. 152, 347 (2005).

Kosako, T., Kadoya, Y. & Hofmann, H. Directional control of light by a nano-optical Yagi–Uda antenna. Nat. Photonics 4, 312–315 (2010).

Kim, J. et al. Babinet-inverted optical Yagi-Uda antenna for unidirectional radiation to free space. Nano Lett. 14, 3072–8 (2014).

Choi, M. et al. A terahertz metamaterial with unnaturally high refractive index. Nature 470, 369–373 (2011).

Teguh Yudistira, H. et al. Fabrication of terahertz metamaterial with high refractive index using high-resolution electrohydrodynamic jet printing. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 21106 (2013).

Rechberger, W. et al. Optical properties of two interacting gold nanoparticles. Opt. Commun. 220, 137–141 (2003).

Prodan, E., Radloff, C., Halas, N. J. & Nordlander, P. A hybridization model for the plasmon response of complex nanostructures. Science 302, 419–22 (2003).

Kats, M. a., Yu, N., Genevet, P., Gaburro, Z. & Capasso, F. Effect of radiation damping on the spectral response of plasmonic components. Opt. Express 19, 21748–53 (2011).

Choe, J., Kang, J., Kim, D. & Park, Q. Slot antenna as a bound charge oscillator. Opt. Express 20, 6521–6526 (2012).

Kang, J., Choe, J., Kim, D. & Park, Q. Substrate effect on aperture resonances in a thin metal film. Opt. Express 17, 15652–15658 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We thank Kyoung-Ho Kim for his help. This work was supported by Nano Material Technology Development Program (No. 2011-0020205) through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), and the Center for Advanced Meta-Materials (CAMM-2014M3A6B3063710). Center for Advanced Meta-Materials was funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning as Global Frontier Project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.H.P. wrote the main manuscript text and S.Y.L. prepared Figures 1–5. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, S., Park, QH. Dynamic coupling of plasmonic resonators. Sci Rep 6, 21989 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep21989

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep21989

This article is cited by

-

Polarization-sensitive and active controllable electromagnetically induced transparency in U-shaped terahertz metamaterials

Frontiers of Optoelectronics (2021)

-

Meta-Optical Chirality and Emergent Eigen-polarization Modes via Plasmon Interactions

Scientific Reports (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.