Abstract

Stingrays commonly cause human envenoming related accidents in populations of the sea, near rivers and lakes. Transcriptomic profiles have been used to elucidate components of animal venom, since they are capable of providing molecular information on the biology of the animal and could have biomedical applications. In this study, we elucidated the transcriptomic profile of the venom glands from two different freshwater stingray species that are endemic to the Paraná-Paraguay basin in Brazil, Potamotrygon amandae and Potamotrygon falkneri. Using RNA-Seq, we identified species-specific transcripts and overlapping proteins in the venom gland of both species. Among the transcripts related with envenoming, high abundance of hyaluronidases was observed in both species. In addition, we built three-dimensional homology models based on several venom transcripts identified. Our study represents a significant improvement in the information about the venoms employed by these two species and their molecular characteristics. Moreover, the information generated by our group helps in a better understanding of the biology of freshwater cartilaginous fishes and offers clues for the development of clinical treatments for stingray envenoming in Brazil and around the world. Finally, our results might have biomedical implications in developing treatments for complex diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Potamotrygonidae family comprises the only group of Elasmobranchii restricted to freshwater environments, with their occurrence limited to some river systems of South America. This group is represented by four genera, among which Potamotrygon comprises the largest number of species with broad geographic distribution1.

The Potamotrygon genus includes benthic freshwater stingrays that are known for their long tail appendage with the presence of one to four serrated bone stings covered by a glandular epithelium whose cells produce venom2,3 (Fig. 1). Injuries caused by stingrays have always been present in riverine communities of inland waters and in South American coasts. Indeed, envenomation by stingrays is quite common in freshwater and marine fishing communities. Although having high morbidity, such injuries are neglected because they have low lethality and usually occur in remote areas, which favor the use of folk remedies2. Moreover, accidents are caused due to a reflex contact between stingrays and humans, yielding an animal tail whiplash and further leading to a sting introduction at the limb during direct contact, causing epithelial lining destruction and subsequent venom release2,4. Clinical manifestations occur by triggering painful processes and injuries, even producing ulcers and necrosis of affected tissues2. Erythema, edema and bleeding of different degrees around the sting site appear in the first poisoning stage following a characteristic cyanosis around the sting with a central necrosis, tissue slackness and the formation of a pink ulcer2.

(A) (a) Stingray spine indicating cross section. (b) Spine cross-sectional view showing mineral region in the center and venom producing glands covering the mineral region. (c) The organization of epithelial cells in the presence of mucus producing glands. (d) Organization of venom producing cells elongated and compressed around the bone of the spine. (e) Distribution of venom producing glands. (B) Potamotrygon falkneri (left) and P. amandae (right) species.

Although several venom-producing animals have been studied across the globe, covering a wide spectrum ranging from aquatic to terrestrial environments, only a few reports have been made on stingrays2,4,5. Although there is currently no work on Potamotrygonidae transcriptomics, some molecules have been isolated in previous works from Potamotrygon orbignyi, such as the vasoconstrictor peptide orpotrin6 and porflan7, a peptide that is able to change vascular and capillary permeability7. Moreover, a single hyaluronidase was isolated from Potamotrygon amandae, which facilitates the absorption and diffusion of venom in the victim’s tissues, increasing systemic poisoning5. Also, recently, the venom gland transcriptome of a marine stingray, Neotrygon kuhlii, was generated8.

Due to the almost complete lack of information about freshwater stingray venoms, a transcriptomic characterization analysis could be a good strategy in order to elucidate components of the stingray venom mixtures, since it provides large amounts of information in a relatively short time9. In fact, venom gland transcriptomic analysis has been developed to study the venoms of organisms10,11. However, the venoms of aquatic animals have been poorly studied.

In this study, the venom gland transcriptome of two different freshwater stingrays, Potamotrygon amandae and Potamotrygon falkneri, was studied. Both species are endemic to the Paraná-Paraguay basin, in Brazil and their specific identity is well corroborated1,12. The metabolic pathways in which venom compounds are produced were then described, providing novel insights into the venom production metabolism in river stingrays, elucidating the relationship between envenomation and the possible molecules associated. Additionally, specific transcripts were selected to do a three-dimensional structural analysis. We believe that our study will shed some light on the transcriptome composition of the venom gland from these animals and it could also have biomedical applications. Furthermore, this study presents the first transcriptomic analysis in freshwater stingrays.

Results

Sequencing and de novo assembly of the P. amandae and P. falkneri transcriptomes

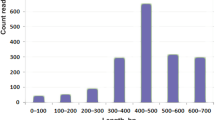

The Illumina MiSeq sequencing of the P. amandae and P. falkneri cDNA libraries generated ~14.5 and ~15.4 million paired-end reads, with average lengths of 231 and 220 bp, respectively. After adapter trimming and quality filtering, we obtained a total of ~13.1 and ~13.7 million high-quality reads, with 92.7 and 92.4% of all bases having Phred (Q) scores above 33, respectively, which indicates good sequencing quality (Table 1). Using the Trinity de novo assembler software13, the high-quality reads were assembled into 147,881 and 105,191 contigs, respectively (Table 1). A length histogram of the P. amandae and P. falkneri assembled contigs shows that for both samples the majority of sequences (68.5 and 63.1%, respectively) ranged from 200 to 599 bp in length and a considerable fraction (18.6 and 23.3%, respectively) were longer than 1 kb (Supplementary Fig. S1).

The assembled contigs of P. amandae and P. falkneri were then subjected to RSEM14 contig abundance analysis, followed by removal of contigs showing low expression (<1 FPKM) and short length (<200 bp). The use of this threshold value of FPKM was based on a RNA-Seq study with Trinity aimed to determine the threshold above which most biologically relevant transcripts are expressed15. Contigs shorter than 200 bp were discarded as likely to be uninformative. Then, the FPKM filtered contigs of P. amandae and P. falkneri were subjected to in silico candidate coding region identification using the TransDecoder software15, resulting in 25,092 and 22,083 contigs, with average lengths of 2,032 and 1,924 bp, respectively (Table 1).

Transcriptome annotation

The P. amandae and P. falkneri filtered contigs were then analyzed for similarities with known sequences against the NCBI non-redundant (nr) peptide database16 using BLASTx17. This resulted in 21,245 (84.7%) and 19,316 (87.5%) significant hits annotated as similar to known proteins or matching known conserved hypothetical proteins, respectively (Table 2). Of these, 81.3 and 83.1% of the BLASTx hits have e-values of at least 1e−40 with the existing proteins at the NCBI nr database and hits with e-value = 0 correspond to 31.8 and 31.6% of the total number of contigs, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S2). Based on the BLASTx hits for the P. amandae and P. falkneri assembled transcripts, the organism names for the top hits were extracted (Fig. 2a), which included matches to the following top four organisms: Callorhinchus milii (50.2 and 51.6%), Latimeria chalumnae (5.9 and 5.8%), Lepisosteus oculatus (1.8 and 1.9%) and Chrysemys picta (1.5 and 1.6%), respectively. In the top 21 organisms shown in Fig. 2a, only seven are fish species that have known genome sequences. This explains the BLASTx hits to more distant species, which is similar to data found in other transcriptomic assemblies of fish species18,19.

(a) Top-hit species distribution after BLASTx similarity search against the NCBI non-redundant (nr) database. (b) Gene Ontology classification of the transcripts separated in three categories: Biological Process, Molecular Function and Cellular Component (c). KEGG Classification of the transcripts separated in six categories: Metabolism, Genetic Information Processing, Environmental Information Processing, Cellular Process, Organismal Systems and Human Diseases. (d) Top 20 most abundant KEGG pathways are shown. Potamotrygon amandae and P. falkneri transcripts are represented in blue and red, respectively.

We further annotated the P. amandae and P. falkneri assembled transcripts with BLASTx against the UniProtKB database. A total of 17,250 (68.8%) and 15,935 (72.2%) transcripts matched to already reported sequences in UniProtKB, respectively (Table 2). Considering the NCBI and UniProtKB BLASTx searches, a total of 3,387 (15.3%) P. amandae and 2,767 (12.5%) P. falkneri transcripts did not result in hits against any of these databases. A closer analysis of these transcripts showed that 3,773 P. amandae and 2,735 P. falkneri harboured an ORF > = 100 amino acids, which suggests that a significant proportion of these could correspond to putative P. amandae and P. falkneri-specific transcripts.

In order to obtain more details about the classification of the proteins, the UniProtKB hits obtained from the BLASTx analysis for both species was crossed against the InterPro database. A total of 16,961 (67.6%) P. amandae and 15,666 (70.9%) P. falkneri assembled transcripts had hits with InterPro entries (Table 2). For P. amandae, the most abundant hits were P-loop containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolase (1168 counts), protein kinase-like domain (746 counts) and zinc finger, C2H2-like (710 counts) (Supplementary Table S1). Similarly, the most abundant hit for P. falkneri was also P-loop containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolase (1076 counts), followed by zinc finger, RING/FYVE/PHD-type (679 counts) and protein kinase-like domain (674 counts) (Supplementary Table S2).

The P. amandae and P. falkneri assembled transcripts which did not result in coding region identification using the TransDecoder software were further analyzed by the PLEK software for the prediction of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs)20. This class of transcripts is involved in important biological processes, such as dosage compensation, regulation of gene expression and cell cycle regulation21. This analysis resulted in the prediction of 1,913 P. amandae and 1,611 P. falkneri putative lncRNAs (Table 2).

Functional and pathway annotations

Gene Ontology (GO) analysis was performed in order to classify the functions of the annotated transcripts. A total of 25,092 P. amandae and 22,083 P. falkneri assembled transcripts were mapped into three categories: biological process, molecular function and cellular components. This analysis resulted in at least one GO term assigned to 64.9 and 69.7% of the transcripts, respectively (Table 2).

Potamotrygon amandae and P. falkneri predicted proteins assigned to biological processes were mainly associated with cellular processes, metabolic processes and biological regulation processes (Fig. 2b). The distribution of the GO terms assigned to molecular functions was reasonably similar to those obtained in the assembled transcriptome of Neotrygon kuhlii8, mainly linked to catalytic activity and binding. Finally, terms assigned to cellular components included cellular locations, cell part and organelles. GO terms for the three categories showed a homogenous distribution between P. amandae and P. falkneri transcripts, with the exception of catalytic activity, which was slightly higher in P. amandae.

The P. amandae and P. falkneri assembled transcriptomes were further annotated by mapping the UniProt accession numbers of the transcripts (obtained from running BLASTx against UniProtKB) onto pathways in KEGG22. A total of 14,131 P. amandae transcripts and 13,147 P. falkneri transcripts were assigned to 269 KEGG pathways corresponding to six categories: “Metabolism”, “Genetic Information Processing”, “Environmental Information Processing”, “Cellular Processes”, “Organismal Systems” and “Human Diseases”. The percentage of assigned transcripts for each of the 37 pathways in these categories is shown in Fig. 2c. It can be seen that the pattern of distribution of the functional categories is similar for the P. amandae and P. falkneri transcriptomes and that the most representative clusters are “Cancers”, “Signal transduction”, “Immune system” and “Infectious diseases”. Interestingly, “Pathways in cancer” were the most abundantly assigned pathways for the P. amandae and P. falkneri transcriptomes, followed by “Endocystosis”, “Focal adhesion”, “MAPK signaling pathway”, “Regulation of actin cytoskeleton” and “Ubiquitin mediated proteolysis” (Fig. 2d).

The metabolism category involves all metabolic pathways present in the stingray spine, including those involved with amino acids, carbohydrate and lipid metabolism, which constitute 51% of all metabolism classes. Within the amino acid metabolism, there were six pathways associated with biosynthetic amino acid pathways in P. amandae and 10 in P. falkneri. Moreover, 113 transcripts from both species were associated to the same amino acid pathways, such as lysine degradation (Supplementary Fig. S3), metabolism of arginine and proline (Supplementary Fig. S4), cysteine and methionine metabolism (Supplementary Fig. S5) and glycine, serine and threonine metabolism (Supplementary Fig. S6). These metabolic pathways clearly show the importance of protein turnover, which could be directly involved in venom protein production.

In the metabolic analysis of carbohydrate pathways, 11 transcripts were exclusive to P. amandae and 14 to P. falkneri and 175 transcripts were shared between both stingrays. Among them, pathways related to the citrate cycle (Supplementary Fig. S7), glycolysis (Supplementary Fig. S8) and pyruvate metabolism (Supplementary Fig. S9) were observed. Among lipid metabolism, 16 transcripts were restricted to P. amandae and 143 were shared between both species, including fatty acid degradation pathways (Supplementary Fig. S10) and metabolism of sphingolipids and glycerophospholipids (Supplementary Figs S11 and S12), being important in cellular degradation.

The SignalP 4.1 software23 was used in order to predict the presence of signal peptide cleavage sites within the assembled transcriptome peptide sequences of both stingrays. A total of 1,441 P. amandae and 1,185 P. falkneri peptide sequences were predicted to contain a signal peptide cleavage site by SignalP (Table 2).

Comparative analysis among four fish species

The UniProtKB database24 currently provides peptide sequences of several fish species which were obtained from transcriptomic studies. Therefore, using BLASTx we compared the assembled transcriptomes of P. amandae and P. falkneri against each other and also against the peptide sequences of two cartilaginous fishes (Callorhincus milii and Latimeria chalumnae) and Danio rerio, the model fish (Fig. 3a,b). A total of 14,033 transcripts expressed in P. amandae were shared among C. milii, L. chalumnae, D. rerio and P. falkneri (Fig. 3a) and 13,021 P. falkneri transcripts were shared among C. milii, L. chalumnae, D. rerio and P. amandae (Fig. 3b). As expected, a significant proportion of transcripts (2,776 in P. amandae and 2,335 in P. falkneri) are shared only between the two stingray species. A search for transcripts that were unique in the stingray species resulted in 3,594 P. amandae unique transcripts and 2,592 P. falkneri unique transcripts. However, only a small proportion of these unique transcripts (208 in P. amandae and 182 in P. falkneri) had BLASTx hits against the UniProtKB database. Most of the unique P. amandae transcripts were mapped to “Translation”, “Transport and Catabolism”, “Infectious diseases” and “Carbohydrate Metabolism” KEGG functional categories, whereas the P. falkneri unique transcripts were mostly mapped to “Translation”, “Cancers”, “Amino Acid Metabolism” and “Folding, Sorting and Degradation” KEGG functional categories.

Venn diagram showing the comparison of the Potamotrygon amandae transcriptome (a) against Callorhincus milii, Latimeria chalumnae, Danio rerio and P. falkneri UniProtKB proteins and the comparison of the P. falkneri transcriptome (b) against C. milii, L. chalumnae, D. rerio and P. amandae UniProtKB proteins. (c) Phylogenetic tree of selected hyaluronidase homologues from various animal species. The tree was constructed by the Maximum Likelihood method in MEGA v.6 with 500 replicates and involved 42 amino acid sequences (UniProtKB accession numbers are shown for each protein). The percentage of bootstrap confidence values is shown at the nodes (only values > 70% are shown). The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. The proteins of P. amandae and P. falkneri are pointed by arrows and black spots indicate the hyaluronidases from venomous organisms.

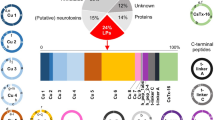

Potamotrygon amandae and P. falkneri transcript hits to UniProtKB Tox-Prot database

In order to evaluate the transcripts related to animal toxin/venoms, a BLASTx analysis was made against the UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot Tox-Prot database25. Several proteins related to the toxins/venoms of many animals were found in this search, such as phospholipase A2, metalloproteinases, c-type lectin, hyaluronidase, serine-proteinases and L-amino acid oxidases, which were ranked in terms of expression abundance in P. amandae and P. falkneri (Tables 3 and 4, respectively).

The identifiable toxin transcripts for P. amandae and P. falkneri represent 111 and 115 PFAM families, respectively. The highest expressed family for both stingray species was glycoside hydrolase, which includes hyaluronidase. This transcript accounted for 63.8 and 44% of the total FPKM for P. amandae and P. falkneri, respectively. The toxin transcript abundances are followed by the CAP protein family (5.7%), EF-hand protein (4.3%), translationally controlled protein (3.5%) and the MANEC domain family in the P. amandae transcriptome and EF-hand protein (5.6%), sea anemone cytotoxic protein family (3.8%), translationally controlled tumour protein (3.4%) and the MANEC domain family (2.9%) in the P. falkneri transcriptome.

In order to better characterize the P. amandae and P. falkneri highly expressed hyaluronidase transcript, a phylogenetic analysis was carried out to discern evolutionary relationships among representative hyaluronidases from a diverse set of organisms. Similarly to the hyaluronidase-like transcript previously identified in the venom gland of the marine stingray N. kuhlii8, the phylogenetic analysis of the P. amandae and P. falkneri hyaluronidase transcripts also revealed that they were non-monophyletic to hyaluronidases previously molecularly characterised from other venomous organisms, such as different fishes and snakes (Fig. 3c).

Theoretical 3D Structural Analysis

In order to assess the three-dimensional theoretical structures of some protein families identified in the stingray transcriptome, as well as to observe the disposition of their catalytic domains, molecular modeling studies were carried out for several predicted toxin transcripts from both stingray species (Fig. 4). BLAST results showed that the selected toxin transcript sequences possessed reliable alignments with template sequences presenting high scores, identity and coverage, as well as low E-values and, for this reason, they were used for further analysis. In this context, a hundred three-dimensional homology models were built for the folowing families: phospholipase A2, serine protease, cysteine-rich secretory protein (CRISP), glycoside hydrolase (hyaluronidase), flavin-containing amine oxidoreductase (L-amino acid oxidase), C-type lectin (CLEC) and vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) for both P. amandae and P. falkneri and disintegrin (snake venom metalloproteinase) only for P. amandae. When evaluated by PROCHECK, these 15 models presented G-factor values, which correspond to the average score for the dihedral angles added to the covalent forces obtained for the main chain, between −0.01 and −0.5. Moreover, Ramachandran’s plot revealed that all structures presented more than 80% of their amino acid residues in the most favorable regions. The ProSa server also confirmed that the Z-scores for these theoretical models are in agreement with Z-scores obtained for proteins structurally resolved by X-ray crystallography or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) techniques available in protein databases. As exceptions, for C-type lectins from both P. amandae and P. falkneri and for VEGFA from P. amandae, it was observed that their theoretical structures were not in agreement with the parameters used for validation procedures. This might be due to an extensive random tail located at their C-terminal region, which did not adopt any stable conformation even after refinement and energy minimization procedures. Due to this, 12 theoretical models with good quality were generated for both stingray species. The physicochemical properties for these models, such as isoelectric point (IP), number of disulfide bonds, solvent-accessible surface area (SASA), as well as α-helix, β-sheet and loop contents, are all summarized in Supplementary Table S3. Among these models, it was also observed that hyaluronidase, CRISP and phospholipase A2 from both P. amandae and P. falkneri, snake venom metalloproteinase from P. amandae and VEGFA from P. falkneri presented conserved residues also reported in the literature and that might play a crucial role in the mechanisms of action of their respective proteins.

(a) Three-dimensional theoretical structures for cysteine-rich secretory protein (CRISP) (green), phospholipase A2 (orange), metalloproteinase (purple), hyaluronidase (cyan) and L-amino acid oxidase (red) from Potamotrygon amandae. The yellow sticks are highlighting the conserved amino acid residues that might display a crucial role in the mechanisms of action of their respective proteins. (b) Three-dimensional theoretical protein structures for cysteine-rich secretory protein (CRISP) (green), phospholipase A2 (orange), vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) (pink), hyaluronidase (cyan) and L-amino acid oxidase (red) from P. falkneri. The yellow sticks are highlighting the conserved amino acid residues that might display a crucial role in the mechanisms of action of their respective proteins.

Taking into account the great importance of some amino acid residues for the correct activity of such proteins, all the reliable theoretical models were superimposed on their template structures, as well as with other members from each enzyme class available in databases, in order to identify conserved residues between them, also highlighting the influence of these residues in the physicochemical properties of the active sites. As observed in Fig. 4, the predicted hyaluronidases, CRISP and phospholipases A2 from both stingray species, as well as VEGFA from P. falkneri and snake venom metalloproteinase from P. amandae, had their activity-related and conserved amino acid residues highlighted, which have been previously described as being crucial elements for the function of these proteins. On the other hand, no residue-related activity was found for L-amino acid oxidase from either stingray species when compared with their template structures or with other similar proteins from databases.

Discussion

The study of stingray transcriptomics is challenging, since there has been little information about this organism published in the literature over the last few years, with freshwater species of the family Potamotrygonidae being completely unexplored. Here, two stingray species were compared according to their transcriptome profiles, showing enormous similarities between them. The single transcriptomic analysis from cartilaginous fish described until now was carried out with the marine blue-spotted stingray, Neotrygon kuhlii8. Notably, the total number of contig sequences obtained for P. amandae and P. falkneri in our work is elevated when compared to the previously assembled N. kuhlii transcriptome, which resulted in only 4,584 contigs8. This is probably due to the higher sequencing coverage done in the present study. Also, our sequence data provides a large number of transcripts for the Potamotrygon genus when compared to publicly available data from the Genbank database where only 255 nucleotide sequences are listed for this genus, mostly from mitochondria.

Furthermore, in the transcriptomic analysis of N. kuhliii, no phospholipase, metalloproteinase or hyaluronidase transcripts were identified. In the freshwater stingrays’ transcriptomic study, the number of transcripts related to venom toxins is much more significant than in N. kuhliii, which might be due to a low sequencing coverage in the N. kuhliii transcriptomics study, or perhaps because freshwater stingray species are in fact richer in venom toxins than marine stingrays.

According to the KEGG analysis from this study, an interesting issue is that metabolic pathways represent a large part of the classes of transcripts found for both stingray species. As mentioned above, the three main pathways associated with metabolism were those related to the metabolism of amino acids, carbohydrates and lipids (Fig. 2c). The main aspect that may be addressed when it comes to amino acid metabolism is protein production. Improvement in protein production leads to venom production, which is used in defense and predation by venomous animals26.

Moreover, polysaccharides were also observed due to their importance in the production of venom by glands, although glycosylation is widely considered a common modification in numerous venom proteins and impacts on their in vivo venomic functions27. Snake venoms, for example, have a large amount of glycoproteins with carbohydrates attached to the N-terminal and these glycosylations are extremely important as they ensure correct folding of the functional domains27.

Several protein families related to envenomation were also observed. The prothrombim activator factors account for the procoagulant nature of the venoms that cause disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC), by activating zymogens in the coagulation cascade28. These proteinases activate the cascade at specific steps because they are analogous to endogenous coagulation factors. Based on their specificity, they could be characterized as factor X activators, prothrombin activators and thrombin-like enzymes29. These enzymes, as well as the others mentioned, represent the great main causes of envenomation with stingrays, since thrombi formed by them may result in more advanced symptoms.

The most highly expressed transcript in both stingray species was hyaluronidase. At the venom composition level, the hyaluronidases are extremely important since they can improve the diffusion of fluids across the skin by hyaluronan degradation, contributing to venom dissemination, potentiating systemic envenomation and demonstrating great potential in local hemorrhage. Similar effects were observed for the Naja naja venom30. Among all toxin transcript families described here, the glycoside hydrolase family, which includes hyaluronidase, is one of the few already previously described in the literature on stingrays5. The symptoms described in P. amandae and P. falkneri envenomations are also conspicuous in hyaluronidase activity5.

Phospholipases A2 play a pivotal role in the biosynthesis of prostaglandin and other inflammation mediators and are abundant in many animal venoms, holding both toxic and digestive characters. They have a vast spectrum of activities, such as neurotoxic, myotoxic, hemolytic, edematogenic, hyperalgesic, pro-inflammatory, hypotensive, platelet-aggregation inhibition, anticoagulant and cytotoxic, being one the most dangerous toxins in animals31. These enzymes have already been described in stingray venom from Dasyatis pastinaca32. Like metalloproteinases, these enzymes are very dangerous in stingray envenoming related accidents and follow the symptomatology that is characterized by hemorrhage and necrosis in the victim’s affected member32.

The proteinases represent the most dangerous venom classes in all venomous organisms because of their characteristic symptoms, which involve severe pain, necrosis and, in some cases, amputation of the affected limbs. Metalloproteinases are normally zinc-dependent enzymes, which play many roles in several venomous animals, such as hemorrhage induction33, inhibition of platelet aggregation33, myonecrosis34 and inflammatory responses34. In addition to hemorrhagic activity, members of the snake venom metalloproteins (SVMP) family also have fibrinogenolytic activity, act as prothrombin activators, activate blood coagulation factor X, possess apoptotic activity, inhibit platelet aggregation and are pro-inflammatory and inactivate blood serine proteinase inhibitors35.

The serine protease and venom prothrombin activator have the same complexity as the cysteine-rich secretory protein/venom allergen factor. Both of these classes have a characteristic trypsin-like serine protease domain36. These serine proteases may act on coagulation cascade components, fibrinolytic and kallikrein–kinin systems and they may cause imbalance of the hemostatic system in cells36. The venom growth nerve factor (VGNF) transcript was also identified for both stingrays. Several VGNF activities have been investigated, including rapid change in phospholipid metabolism, change in ion flux across the plasma membrane and phosphorylation of specific proteins, as well as synthesis induction and release of neurotransmitters, symptoms observed for the pit viper Crotalus adamanteus venom37. This factor also induced weak vascular permeability, suggesting its involvement in the hemorrhagic activity of the venom of Viperaxantina paslestinae38.

Other venom families described here were the cysteine-rich secretory proteins (CRISPs). The CRISPs are glycoproteins found exclusively in vertebrates and have diverse functions39. In mammalian reproduction and reptilian venom, they are hypothesized to disrupt the homeostasis of their prey across several mechanisms, including blockage of cyclic nucleotide-gated and voltage-gated ion channels and inhibition of smooth muscle contraction39.

Two neurotoxins were found in both stingrays’ transcriptomes: ohanin and α-atrotoxin-Lt1a. Neurotoxins may act in neuromuscular transmission where the neurotransmitter is acetylcholine, but on some occasions these toxins may interfere with neurotransmitters such as adrenaline, dopamine, GABA, noradrenaline and γ-aminobutyrate40. Ohanin has been purified from Ophiophagus hannah (king cobra) venom and it was shown to induce hypolocomotion and hyperalgesia in mice, suggesting its action through the central nervous system40. α-Latrotoxin-Lt1a is a neurotoxin from the European black widow spider (Latrodectus tredecimguttatus), which causes massive vesicle exocytosis leading to muscle fasciculation, tremor and muscle paralysis41.

In addition to gathering information about the biology of these organisms, studies generating transcriptome analyses of venom glands have several biomedical applications. For example, understanding the variations in protein components is instrumental in interpreting clinical symptoms during human envenomation and in searching for novel venom proteins with potential therapeutic applications42. In the last decade, transcriptomic analyses of venom glands have helped in understanding the composition of various snake venoms in great detail42. Additionally, proteins from venoms of different organisms have been used to develop drugs specific for complex diseases such as cancer43. In our study, it is noteworthy the fact that we identified in our KEGG analysis (Fig. 2c,d) several transcripts that are classified as “disease related”, especially for cancer, neurodegenerative and infectious diseases. In that regard, it is well recognized that animal venoms have been potentially rich sources of biologically active biomolecules that could be mined for the discovery of drugs, drug leads and/or biosimilars44. A proof of concept is a novel approach to explore venoms for potential biosimilarity to other drugs based on their ability to alter the transcriptomes of test cell lines followed by informatic searches and using the Connectivity Mapping to match the action of the venom on the cell gene expression to that of other drugs in the Connectivity Map database44. Thus, we believe that the transcripts identified in our study could be further evaluated for biomedical applications, especially those related to drug development and new therapies for complex diseases.

Conclusions and Future Prospects

In summary, the transcriptomes of two freshwater stingray venoms were described and several transcripts were presented and their possible relationship with the envenoming and venom of different animals was discussed here. Different types of putative toxins correlate to the symptomatology present in riverine population affected by these accidents. For this reason, the knowledge and study of these species are extremely important, since these populations are completely neglected and literature has just little description on the molecular mechanisms of these accidents. On the other hand, this study also represents significant gains (or improvements) in the information about the Potamotrygon genus, which was described for the first time using transcriptomic analytics’ tools. Our study also helps in a better understanding on the biology of freshwater cartilaginous fishes and could have several biomedical applications for drug development studies.

Materials and Methods

Stingray spine collection and RNA isolation

Spine samples from two species of freshwater stingrays, Potamotrygon amandae (n = 3 specimens) and Potamotrygon falkneri (n = 3 specimens), were collected from the Paraná River, in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, Midwest of Brazil (about 20°47′S 51°37′W). Since the spines regenerate, all specimens captured were released after extraction of the spine. All collection procedures also respected the integrity of the animals and were carried out under consent and in accordance with the approved guidelines of the Brazilian Environmental Agency (License ICMBio n°31241-4).

RNA Extraction

Following tissue extraction, the spines were immediately frozen in dry ice and conserved in RNAlater Stabilization Reagent (QIAGEN). In order to obtain venom gland secretory material, the spines of the three specimens of each species were scraped in pool and 100 mg of both materials were used for RNA extraction with TRIzol Reagent Purification kit (Life Technologies), according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. RNA concentration was measured using Qubit RNA Assay Kit (Life Technologies) and RNA integrity was confirmed by visualization of electrophoresed RNA on an ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel. For greater accuracy, RNA quality was assessed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer machine (Agilent Technologies) before cDNA library construction.

cDNA library construction and sequencing

The cDNA libraries of both samples, each containing pooled RNA from three specimens, were constructed using the TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Kit v2 (Illumina), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Library quantity and quality was assessed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). Finally, both cDNA libraries were sequenced (2 × 250 bp paired-ends) on two separate Illumina MiSeq runs by the sequencing facility at the Catholic University of Brasília. After sequencing, samples were individualized according to their indexes and converted to fastq format using the MiSeq Reports (Illumina) program. Raw data from the sequencing runs were submitted to the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) repository of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under accession number SRR2039259.

Sequence data pre-processing and transcriptome assembly

In order to perform quality trimming of the fastq files obtained from Illumina MiSeq sequencing, pre-processing was carried out using the Trimmomatic tool45 using the following parameters: sliding window:4:20; leading: 10; trailing: 10; minlen: 40. All sequences smaller than 40 bases were eliminated on the assumption that small reads might represent sequencing artifacts. Also, Trimmomatic verified the presence and removed adapter sequences that matched entries in a FASTA file containing all known Illumina adapters. Quality assessment of the Trimmomatic pre-processed data was carried out using the FastQC tool (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk), which confirmed that poor quality bases were removed. The resulting high quality reads were then assembled into contigs using the Trinity de novo assembly software13. In order to reduce redundancy, the program cap346 was used to merge contigs with overlap length cutoff of 200 and overlap identity cutoff of 99 and contigs showing low expression (<1 FPKM) were removed. Parameters used for the Trinity assembly included a maximum memory of 30 Gigabytes, threaded on 60 processors and a fastq sequence type. Trinity assembly, as well as all other analyses that employed high performance computers (HPCs), were done on a SGI uv100 computer system running SUSE Linux located at the Bioinformatics Laboratory of the Catholic University of Brasília.

Transcriptome abundance estimation

In order to compute abundance estimates of the assembled transcriptome, the pre-processed high quality reads were aligned to the Trinity contigs using the Bowtie read aligner47. Then, based on the resulting alignments, the RNA-Seq by Expectation Maximization (RSEM) tool14 was used to estimate transcript abundance in terms of Fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped (FPKM).

Transcriptome, functional and pathway annotations

Transcripts containing coding sequences

In order to filter out likely transcript artifacts and noise, prior to annotation, the assembled transcripts were filtered based on minimum length (> = 200 bp) and expression value (> = 1 FPKM). These transcripts were then analyzed by the TransDecoder software15, contained within the Trinity package13, which identifies candidate coding regions within transcript sequences. To detect transcript similarities with other species, the filtered transcripts were subjected to a BLASTx analysis17 (with e-value threshold of 10−5 and matching to the top hits) against the following databases: NCBI nonredundant (nr) protein sequences16, UniProtKB24 and UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot Tox-Prot25. The Trinotate software15, contained within the Trinity package13, was used for functional annotation, including Gene Ontology (GO) terms48 and presence and location of signal peptide cleavage sites (SignalP)23. The Web Gene Ontology Annotation Plotting (WEGO)49 online tool was then used for visualizing and comparing our GO annotation for both species. Based on BLASTx matches to UniProtKB sequences24, the Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway22 and InterPro50 databases were searched in order to include these annotations to the assembled transcripts.

Transcripts without coding sequences

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) present in the assembled transcriptomes were searched using the PLEK software20, which attempts to distinguish lncRNA from protein-coding sequences in high-throughput sequencing without reference genomes or annotations. This software uses a computational pipeline based on an improved k-mer scheme and a support vector machine algorithm to distinguish lncRNAs from protein-coding sequences20. The summary of the whole transcriptome analysis workflow is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S14.

Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Analysis

The highest expressed hyaluronidase transcript hits obtained from the P. amandae and P. falkneri transcriptomes were selected for alignment with a diverse set of hyaluronidase sequences obtained from other species, including venomous organisms (Bitis arietans, Echis ocellatus, Cerastes cerastes, Echis pyramidum leakeyi, Synanceia horrida, Synanceia verrucosa, Pterois antennata and Pterois volitans). The UniProtKB accession numbers of the 42 protein sequences selected for comparison are listed in Table S4. The selected sequences were aligned with the Clustal Omega Multiple Sequence Alignment software51 (Fig. S13) and a Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic tree based on the JTT matrix-based model52 was created using the Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software, version 653. The JTT matrix-based model52 was selected as the best-fit model by both MEGA53 and ProtTest54 softwares. Confidence values for phylogenetic tree branching were generated by the bootstrap method (500 replicates)55. FigTree 1.4 was used to produce the phylogenetic tree figure.

Molecular Modeling

For molecular modeling studies, 13 toxin transcript sequences obtained from the assembled transcriptomes of P. amandae and P. falkneri were analyzed. The families that were analyzed were the following: phospholipase A2, serine protease, cysteine-rich secretory protein (CRISP), glycoside hydrolase (hyaluronidase), flavin-containing amine oxidoreductase (L-amino acid oxidase), C-type lectin (CLEC) and vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) for both P. amandae and P. falkneri and disintegrin (snake venom metalloproteinase) only for P. amandae. Phobius server56 was used in order to predict signal peptide and intermembrane regions, which were not considered for further analysis. Protein-protein BLAST17 was also carried out in order to find the best template sequences for molecular modeling. By using Modeller v 9.1257, 100 three-dimensional homology models were built and ranked by their free energy values. Those models with lowest free energy were then selected and validated according to their geometry, stereochemistry and energy distributions by using PROCHECK58. ProSA-web server59 was also used to calculate an overall quality score for the selected theoretical models in comparison with those scores for proteins structurally resolved by X-ray crystallography or Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) techniques.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Júnior, N. G. O. et al. Venom gland transcriptome analyses of two freshwater stingrays (Myliobatiformes: Potamotrygonidae) from Brazil. Sci. Rep. 6, 21935; doi: 10.1038/srep21935 (2016).

References

Carvalho, M. R., Lovejoy, N. R. & Rosa, R. S. Check List of the Freshwater Fishes of South and Central America. (EDIPUCRS, 2003).

Haddad, V., Neto, D. G., de Paula Neto, J. B., de Luna Marques, F. P. & Barbaro, K. C. Freshwater stingrays: study of epidemiologic, clinic and therapeutic aspects based on 84 envenomings in humans and some enzymatic activities of the venom. Toxicon 43, 287–94 (2004).

Barbaro, K. C. et al. Comparative study on extracts from the tissue covering the stingers of freshwater (Potamotrygon falkneri) and marine (Dasyatis guttata) stingrays. Toxicon 50, 676–87 (2007).

Pedroso, C. M. et al. Morphological characterization of the venom secretory epidermal cells in the stinger of marine and freshwater stingrays. Toxicon 50, 688–97 (2007).

Magalhães, M. R., da Silva, N. J. & Ulhoa, C. J. A hyaluronidase from Potamotrygon motoro (freshwater stingrays) venom: isolation and characterization. Toxicon 51, 1060–7 (2008).

Conceição, K. et al. Orpotrin: a novel vasoconstrictor peptide from the venom of the Brazilian stingray Potamotrygon gr. orbignyi. Peptides 27, 3039–46 (2006).

Conceição, K. et al. Characterization of a new bioactive peptide from Potamotrygon gr. orbignyi freshwater stingray venom. Peptides 30, 2191–9 (2009).

Baumann, K. et al. A ray of venom: Combined proteomic and transcriptomic investigation of fish venom composition using barb tissue from the blue-spotted stingray (Neotrygon kuhlii). J. Proteomics 109, 188–98 (2014).

Magalhães, G. S. et al. Transcriptome analysis of expressed sequence tags from the venom glands of the fish Thalassophryne nattereri. Biochimie 88, 693–9 (2006).

Margres, M. J., Aronow, K., Loyacano, J. & Rokyta, D. R. The venom-gland transcriptome of the eastern coral snake (Micrurus fulvius) reveals high venom complexity in the intragenomic evolution of venoms. BMC Genomics 14, 531 (2013).

He, Q. et al. The Venom Gland Transcriptome of Latrodectus tredecimguttatus Revealed by Deep Sequencing and cDNA Library Analysis. PLoS One 8, e81357 (2013).

Loboda, T. S. & Carvalho, M. R. de . Systematic revision of the Potamotrygon motoro (Müller & Henle, 1841) species complex in the Paraná-Paraguay basin, with description of two new ocellated species (Chondrichthyes: Myliobatiformes: Potamotrygonidae). Neotrop. Ichthyol. 11, 693–737 (2013).

Grabherr, M. G. et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 644–52 (2011).

Li, B. & Dewey, C. N. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 323 (2011).

Haas, B. J. et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 8, 1494–512 (2013).

Sayers, E. W. et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, D38–51 (2011).

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–10 (1990).

Long, Y. et al. De novo assembly of mud loach (Misgurnus anguillicaudatus) skin transcriptome to identify putative genes involved in immunity and epidermal mucus secretion. PLoS One 8, e56998 (2013).

Huang, L. et al. De Novo assembly of the Japanese flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) spleen transcriptome to identify putative genes involved in immunity. PLoS One 10, e0117642 (2015).

Li, A., Zhang, J. & Zhou, Z. PLEK: a tool for predicting long non-coding RNAs and messenger RNAs based on an improved k-mer scheme. BMC Bioinformatics 15, 311 (2014).

Flintoft, L. Non-coding RNA: Structure and function for lncRNAs. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14, 598 (2013).

Kanehisa, M. et al. Data, information, knowledge and principle: back to metabolism in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D199–205 (2014).

Petersen, T. N., Brunak, S., von Heijne, G. & Nielsen, H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat. Methods 8, 785–6 (2011).

The UniProt Consortium. UniProt: a hub for protein information. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D204–212 (2014).

Jungo, F., Bougueleret, L., Xenarios, I. & Poux, S. The UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot Tox-Prot program: A central hub of integrated venom protein data. Toxicon 60, 551–7 (2012).

Morgenstern, D. & King, G. F. The venom optimization hypothesis revisited. Toxicon 63, 120–8 (2013).

Soares, S. G. & Oliveira, L. L. Venom-sweet-venom: N-linked glycosylation in snake venom toxins. Protein Pept. Lett. 16, 913–9 (2009).

Hutton, R. A. & Warrell, D. A. Action of snake venom components on the haemostatic system. Blood Rev. 7, 176–89 (1993).

Joseph, J. S., Chung, M. C. M., Mirtschin, P. J. & Kini, R. M. Effect of snake venom procoagulants on snake plasma: implications for the coagulation cascade of snakes. Toxicon 40, 175–83 (2002).

Fox, J. W. A brief review of the scientific history of several lesser-known snake venom proteins: l-amino acid oxidases, hyaluronidases and phosphodiesterases. Toxicon 62, 75–82 (2013).

Gutiérrez, J. M. & Lomonte, B. Phospholipases A2: unveiling the secrets of a functionally versatile group of snake venom toxins. Toxicon 62, 27–39 (2013).

Ben Bacha, A., Abid, I., Horchani, H. & Mejdoub, H. Enzymatic properties of stingray Dasyatis pastinaca group V, IIA and IB phospholipases A(2): a comparative study. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 62, 537–42 (2013).

Gutiérrez, J. M., Rucavado, A., Escalante, T. & Díaz, C. Hemorrhage induced by snake venom metalloproteinases: biochemical and biophysical mechanisms involved in microvessel damage. Toxicon 45, 997–1011 (2005).

Fox, J. W. & Serrano, S. M. T. Structural considerations of the snake venom metalloproteinases, key members of the M12 reprolysin family of metalloproteinases. Toxicon 45, 969–85 (2005).

Markland, F. S. & Swenson, S. Snake venom metalloproteinases. Toxicon 62, 3–18 (2013).

Rawlings, N. D. & Barrett, A. J. Families of serine peptidases. Methods Enzymol. 244, 19–61 (1994).

Osipov, A. V. et al. Nerve growth factor from cobra venom inhibits the growth of Ehrlich tumor in mice. Toxins (Basel). 6, 784–95 (2014).

Momic, T. et al. Pharmacological aspects of Vipera xantina palestinae venom. Toxins (Basel). 3, 1420–32 (2011).

Sunagar, K., Johnson, W. E., O’Brien, S. J., Vasconcelos, V. & Antunes, A. Evolution of CRISPs associated with toxicoferan-reptilian venom and mammalian reproduction. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 1807–22 (2012).

Pung, Y. F., Wong, P. T. H., Kumar, P. P., Hodgson, W. C. & Kini, R. M. Ohanin, a novel protein from king cobra venom, induces hypolocomotion and hyperalgesia in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 13137–47 (2005).

Graudins, A. et al. Cloning and activity of a novel α-latrotoxin from red-back spider venom. Biochem. Pharmacol. 83, 170–83 (2012).

Brahma, R. K., McCleary, R. J. R., Kini, R. M. & Doley, R. Venom gland transcriptomics for identifying, cataloging and characterizing venom proteins in snakes. Toxicon 93, 1–10 (2015).

Calderon, L. A. et al. Antitumoral activity of snake venom proteins: new trends in cancer therapy. Biomed Res. Int. 2014, 203639 (2014).

Aramadhaka, L. R., Prorock, A., Dragulev, B., Bao, Y. & Fox, J. W. Connectivity maps for biosimilar drug discovery in venoms: the case of Gila monster venom and the anti-diabetes drug Byetta®. Toxicon 69, 160–7 (2013).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–20 (2014).

Huang, X. & Madan, A. CAP3: A DNA sequence assembly program. Genome Res. 9, 868–77 (1999).

Langmead, B., Trapnell, C., Pop, M. & Salzberg, S. L. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 10, R25 (2009).

Ashburner, M. et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 25, 25–9 (2000).

Ye, J. et al. WEGO: a web tool for plotting GO annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W293–W297 (2006).

Mitchell, A. et al. The InterPro protein families database: the classification resource after 15 years. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D213–21 (2014).

Sievers, F. et al. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7, 539 (2011).

Guindon, S. & Gascuel, O. A simple, fast and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst. Biol. 52, 696–704 (2003).

Tamura, K., Stecher, G., Peterson, D., Filipski, A. & Kumar, S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–9 (2013).

Darriba, D., Taboada, G. L., Doallo, R. & Posada, D. ProtTest 3: fast selection of best-fit models of protein evolution. Bioinformatics 27, 1164–5 (2011).

Felsenstein, J. Confidence Limits on Phylogenies: An Approach Using the Bootstrap. Evolution (N. Y). 39, 783 (1985).

Käll, L., Krogh, A. & Sonnhammer, E. L. L. Advantages of combined transmembrane topology and signal peptide prediction—the Phobius web server. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W429–32 (2007).

Eswar, N. et al. Comparative protein structure modeling using MODELLER. Curr. Protoc. Protein Sci. Chapter 2, Unit 2.9 (2007).

Laskowski, R., Macarthur, M., Moss, D. & Thornton, J. {PROCHECK}: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Cryst. 26, 283–291 (1993).

Wiederstein, M. & Sippl, M. J. ProSA-web: interactive web service for the recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W407–10 (2007).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.A.A., N.O.J. and O.L.F. conceived and designed the experiments, E.S.C., D.G.N., M.R.M. and E.F.S. performed the experiments, S.A.A., N.O.J., G.R.F., F.F.C. and M.H.C. analyzed the data, S.A.A., F.F.C, M.H.C., N.O.J. and O.L.F wrote the paper. All authors have reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Júnior, N., Fernandes, G., Cardoso, M. et al. Venom gland transcriptome analyses of two freshwater stingrays (Myliobatiformes: Potamotrygonidae) from Brazil. Sci Rep 6, 21935 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep21935

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep21935

This article is cited by

-

Health assessment of rice cultivated and harvested from plasma-irradiated seeds

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Detection of NO3− introduced in plasma-irradiated dry lettuce seeds using liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization quantum mass spectrometry (LC-ESI QMS)

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Current status and future perspectives of Neotropical freshwater stingrays (Potamotrygoninae, Myliobatiformes) genetics

Environmental Biology of Fishes (2022)

-

Phylotranscriptomics suggests the jawed vertebrate ancestor could generate diverse helper and regulatory T cell subsets

BMC Evolutionary Biology (2018)

-

De novo characterization of venom apparatus transcriptome of Pardosa pseudoannulata and analysis of its gene expression in response to Bt protein

BMC Biotechnology (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.