Abstract

In surface science and model catalysis, cerium oxide (ceria) is mostly grown as an ultra-thin film on a metal substrate in the ultra-high vacuum to understand fundamental mechanisms involved in diverse surface chemistry processes. However, such ultra-thin films do not have the contribution of a bulk ceria underneath, which is currently discussed to have a high impact on in particular surface redox processes. Here, we present a fully oxidized ceria thick film (180 nm) with a perfectly stoichiometric CeO2(111) surface exhibiting exceptionally large, atomically flat terraces. The film is well-suited for ceria model studies as well as a perfect substitute for CeO2 bulk material.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cerium oxide (ceria) is a most important material in heterogeneous catalysis1 due to its high oxygen storage capacity (OSC) based on the oxidation and reduction of cerium ions2. It is used in the water-gas-shift reaction and for the oxidation of hydrocarbons2, with the most prominent application being the three-way-catalyst3,4.

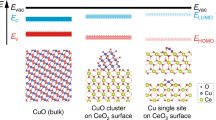

To understand redox processes and related surface chemistry5 at the atomic scale, ultra-thin ceria films have been used as model systems in surface science and heterogeneous model catalysis. In particular, the CeO2(111)6,7,8 and its reduced variant Ce2O3(111)9,10 have been studied and both reduction as well as re-oxidation have been demonstrated10,11,12,13,14. However, such studies are not suitable for understanding surface processes on thick ceria material as oxygen diffusion from the bulk may strongly influence the surface reaction state2. Applications of ceria in catalysis, sensor technology as well as ceria catalysis model studies require materials with a well-defined surface and oxygen storage capacity.

Recently, a method for the growth of 150 to 250 nm thick fully oxidized ceria films on Si(111) by molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) has been proposed15,16 and such films were suggested as an easy-to-prepare material to replace bulk ceria crystals15,17,18 that are most difficult to grow19. We show that a straightforward three step procedure in ultra-high vacuum (UHV) following MBE growth of the film yields a fully oxidized CeO2(111) surface with exceptionally wide, clean and atomically flat terraces. This is substantiated by UHV noncontact atomic force microscopy (NC-AFM) and photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements. Our work demonstrates that even ceria surfaces that are exposed to the ambient air and transferred into the UHV can be cleaned and oxidized by this three step procedure.

Results

In previous work, we found that annealing the ceria film in UHV at temperatures above 1050 K yields the high-temperature surface morphology characterized by large atomically rough terraces18 and a strong (near-)surface reduction17. Step-wise annealing the sample in air yields similar results as demonstrated by the series of AFM images shown in Fig. 1, representing five heating and cooling cycles performed on one sample with maximum temperatures of 1080 and 1100 K, respectively. For the first two annealing steps performed at 1080 K (Fig. 1(a)), remainders of pyramids dominating the low-temperature surface morphology are found as for films annealed in UHV18. After the fourth and in particular the fifth annealing cycle where the temperature is increased to 1100 K to accelerate the surface transformation, the surface is considerably flattened exhibiting mainly layered islands, some of them approaching a hexagonal shape (Fig. 1(d,e)) like on the surface of bulk crystals20.

Development of the surface morphology of a ceria film subjected to consecutive annealing cycles performed at 1080 (a–c) and 1100 K (d,e) as determined by tapping mode AFM measurements in air. The specified times denote the total time of the heating part of each annealing cycle (see Fig. S1 in the Supplemental Material), whereas the specified maximum temperature is kept for at least 1 h. Image size of all images: 1.0 × 1.0 μm2, color coded height scale: 14.0 nm (a–c), 5.0 nm (d) and 6.3 nm (e) correspond to white color.

In the images shown in Fig. 1, terraces appear as rather flat and intersected by steps with a height of integer multiples of the 0.315 nm triple-layer step height. However, when imaging the air-annealed film by NC-AFM in UHV, the terraces do not appear atomically flat, as it can be seen in the topography image of Fig. 2(a,b): apart from the step and terrace structure, a granular structure formed by small features with a height below 0.3 nm covers the terraces (see black profile in Fig. 2(h)). This is similar to granular structures observed on other dielectric crystals like CaF2(111)21 and MgO(001)22, in particular after air exposure.

NC-AFM topography images obtained in UHV on a film annealed in air.

(a,b) Surface after air-annealing. (c,d) Surface after annealing in UHV at 925 K for 1 h. (e,f) Surface after annealing in oxygen  mbar) at 938 K for 1 h. (g) Surface after Ar+ bombardment

mbar) at 938 K for 1 h. (g) Surface after Ar+ bombardment  mbar, 1.5 keV, 5 min) and annealing in oxygen

mbar, 1.5 keV, 5 min) and annealing in oxygen  mbar) at 1008 K for 1 h. Image sizes: 500 × 500 nm2 (a,c,e,g), 100 × 100 nm2 (b,d,f), color coded height scale: 1.5 nm (a), 1.2 nm (b), 1.5 nm (c), 1.5 nm (d), 3.1 nm (e), 3.1 nm (f) and 9.4 nm (g). (h) Height profiles taken along the lines in images (b,d,f,g). Line colors in NC-AFM images correspond to line colors of the profiles.

mbar) at 1008 K for 1 h. Image sizes: 500 × 500 nm2 (a,c,e,g), 100 × 100 nm2 (b,d,f), color coded height scale: 1.5 nm (a), 1.2 nm (b), 1.5 nm (c), 1.5 nm (d), 3.1 nm (e), 3.1 nm (f) and 9.4 nm (g). (h) Height profiles taken along the lines in images (b,d,f,g). Line colors in NC-AFM images correspond to line colors of the profiles.

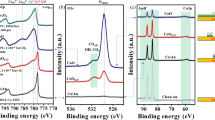

To reveal the oxidation state of the ceria film and surface contaminants, we analyze the Ce3d, O1s and C1s peaks of XPS spectra taken after different preparation steps as shown in Fig. 3. By analyzing survey spectra (not shown), we make sure not to miss any contamination. Details of the quantitative spectral analysis by fitting model curves to spectral features are given in the Supplementary Information. To determine the relative content of Ce3+ in the film, we first analyze the Ce3d spectra by relating the area of the Ce3+ doublet  to the total multiplet area

to the total multiplet area  and determine the reduction state in % by calculating the fraction

and determine the reduction state in % by calculating the fraction  10 as shown in Fig. 3(a). The uncertainties on the fraction is estimated to be around ±5% (see Supplementary Information).

10 as shown in Fig. 3(a). The uncertainties on the fraction is estimated to be around ±5% (see Supplementary Information).

XPS Ce3d (a), O1s (b) and C1s (c) spectra taken on a ceria film in different states of preparation. The sequence of preparation steps is: as-grown, annealing in air, annealing in UHV (923 K, 1 h), two times annealing in oxygen  mbar, 934 and 938 K, each 1 h) and sputtering

mbar, 934 and 938 K, each 1 h) and sputtering  mbar, 1.0 keV, 15 min) followed by annealing in oxygen

mbar, 1.0 keV, 15 min) followed by annealing in oxygen  mbar, 1040 K, 1 h). Circles denote measured points while the solid lines are fit curves. The Ce3+ and O-Ce3+ peaks are in blue, whereas the Ce4+ and O-Ce4+ peaks are in red. The assignment of peaks 1 to 4 in frame (b) is given in the main text.

mbar, 1040 K, 1 h). Circles denote measured points while the solid lines are fit curves. The Ce3+ and O-Ce3+ peaks are in blue, whereas the Ce4+ and O-Ce4+ peaks are in red. The assignment of peaks 1 to 4 in frame (b) is given in the main text.

Next, we analyze the O1s spectra shown in Fig. 3(b) by fitting the spectrum with 4 Gaussian functions at 530.2 eV (peak 1), 531.4 eV (peak 2), 532.6 eV (peak 3) and 533.3 eV (peak 4). Peak 1 and 2 are assigned to oxygen bound to Ce4+ and Ce3+, respectively23,24 whereas peak 3 is assigned to hydroxyls and/or H2O molecules bound to Ce3+ 25,26. From Peaks 1 and 2, we extract the relative content of Ce3+. Note, however, that signals for the O1s peak originate from significantly deeper layers (~1.5 nm) than signals from the Ce3d peak (~1.0 nm) explaining different values for the reduction state27. Peak 4 remains constant during all thermal treatment steps and is associated to SiO228 originating from oxidized silicon particles contaminating the film during cutting the Si wafer. This interpretation is supported by the observation that a 2s and 2p peak of SiO2 at 106 eV and 156 eV, respectively, are observed in related survey spectra (not shown). A segregation of Si from the substrate to the surface can, however, be excluded as this takes place only at temperatures high enough to destroy the film29.

From the Ce3d spectrum it can be concluded that the Ce3+ concentration of the as-grown film is 26% and decreases to 15% during air annealing indicating that the surface of the film is significantly oxidized. This trend of oxidation is weaker in deeper layers since the O-Ce3+ peak becomes only slightly smaller in the O1s spectra (from 23 to 20%). The hydroxyl peak in the O1s spectrum is, however, not affected by annealing in air. As it can be seen in the C1s spectrum (Fig. 3(c)), the as-grown film is, furthermore, contaminated with carbon containing species. However, the C1s peak decreases significantly upon annealing the film in air. We anticipate that oxygen from the air reacts off carbon containing species.

In an attempt to completely remove carbon and hydroxyl containing species, we anneal the sample in UHV for one hour at a temperature of 850 K in the XPS chamber and similarly at 925 K in the AFM chamber. After such annealing, the film is strongly reduced as the surface Ce3+ concentration in the Ce3d spectra increases to 42%, accompanied by a reduction in deeper layers (30%, O1s spectrum). Surface cleaning by this step is immediately evident from the O1s spectra. The hydroxyl peak 3 disappears completely as hydroxyls and water desorb at temperatures higher than 400 K25,26. However, in the highly resolved NC-AFM images of Fig. 2(c,d), the granular structure is still visible, although, reduced to some extent. Interestingly, the C1s XPS peak increases (Fig. 3(c)) what we attribute to residual carbon segregating from subsurface regions to the surface.

After the reduction of the ceria film by UHV annealing, we seek for a re-oxidation and anneal the film for one hour at 938 K (AFM) and 923 K (XPS), in molecular oxygen ( mbar). The NC-AFM topography images in Fig. 2(e,f) clearly show, that the granular structure disappears and that the terraces are almost atomically flat. Surface cleaning is also reflected in the carbon C1s peak almost completely disappearing already after the first oxygen annealing step and being reduced to zero in the second annealing step. However, annealing in oxygen does not only clean the surface but also strongly oxidizes the film what is reflected in the Ce3+ concentration decreasing from 42% first to 26% and then to 9% in the second oxygen annealing step at 934 K.

mbar). The NC-AFM topography images in Fig. 2(e,f) clearly show, that the granular structure disappears and that the terraces are almost atomically flat. Surface cleaning is also reflected in the carbon C1s peak almost completely disappearing already after the first oxygen annealing step and being reduced to zero in the second annealing step. However, annealing in oxygen does not only clean the surface but also strongly oxidizes the film what is reflected in the Ce3+ concentration decreasing from 42% first to 26% and then to 9% in the second oxygen annealing step at 934 K.

Based on the XPS results, we assign the topographic features seen in Fig. 2(a,b) to carbon and hydroxyl containing species where the hydroxyl containing species can be removed by annealing in UHV while carbon contaminants visible in Fig. 2(c,d) can be only removed by annealing in molecular oxygen. Already after the first annealing in oxygen, an almost stoichiometric and almost atomically flat CeO2(111) surface as shown in Fig. 2(e,f) is obtained.

The only surface contaminant that cannot be removed by heat and oxygen treatment are the SiO2 particles. As samples are carefully rinsed with water and wiped after cutting the wafer, we anticipate that residual SiO2 particles are very small and fill some of the many pits left by surface preparation. To remove this contaminant, we sputter-clean the film with Ar+ ions and anneal again for one hour at 1008 K in molecular oxygen. After this final preparation step, we obtain a surface with atomically flat terraces having an extension of up to several 100 nm, intersected by one to three triple-layer high steps as seen in Fig. 2(g) and line profiles compiled in Fig. 2(h). The step edges form angles of 60 and 120 , as expected for the growth of a high-quality CeO2(111) surface. The analysis of XPS spectra reveals that the SiO2 contamination can effectively be removed as evident from the extremely small peak 4 in the respective O1s spectrum shown in Fig. 3(b). Another remarkable result is that the surface is now almost completely oxidized. Note, that the final values of 6% and 7% for the Ce3+ concentration determined from the analysis of the Ce3d and O1s peaks are very close to each other indicating that not only the surface but also near surface layers are finally well oxidized.

Conclusions

In conclusion, a stoichiometric CeO2(111) surface with exceptionally wide atomically flat terraces and a reservoir of oxygen in near surface layers can be prepared on a thick ceria film by a combination of simple procedures comprising annealing in air, sputter-cleaning and annealing in UHV and annealing in UHV back-filled with oxygen. The surface quality and purity of this system is better or at least equal compared to what can be expected from a well-prepared surface of a grown bulk crystal.

Whereas the sputtering-cleaning is a particular preparation step needed for the ceria-silicon system to remove residual SiO2 contaminants from the surface, the annealing in molecular oxygen is needed to fully oxidize the surface but also to remove contaminants like hydroxyls and carbon containing surface species if the film has been exposed before to the ambient air. With respect to the latter, we propose that any air-exposed ceria surface can be cleaned and fully oxidized by a high-temperature annealing in molecular oxygen such that ceria samples can be transported in air between two UHV systems.

In general, due to its simplicity of MBE growth, surface preparation and integration into silicon technology, the thick ceria film we present here is an ideal choice for surface science studies, catalysis research and applications where a well-prepared ceria surface with oxygen storage capacity is required.

Methods

Ceria films with a thickness of 180 nm are grown in one batch with a 3 nm thick hexagonal Pr2O3(0001) buffer layer on Si(111) by MBE as described earlier15, cut from the wafer into pieces of 10 × 10 mm2 by an abrasive wire saw and then stored for several months under ambient laboratory conditions. To reveal the surface morphology and its change during preparation, tapping mode atomic force microscopy (XE 100 AFM, Park Scientific (Suwon, Korea) and Nanoscope Multimode III, Bruker (Billerica MA, USA)) is used for surface imaging under ambient conditions and NC-AFM is accomplished in UHV (RT-AFM/STM, Scienta Omicron GmbH (Taunusstein, Germany)). For studying the development of the surface stoichiometry, samples from the same batch are subjected to the same thermal treatment and analyzed by XPS in a second UHV system (un-monochromatized X-ray source, PSP Vacuum Technology (Macclesfield, UK)). The first preparation step is always annealing the sample in air with a furnace providing temperatures of up to 1100 K. For annealing in UHV, a furnace mounted in the NC-AFM vacuum chamber is used22 while heating in the XPS system is accomplished by electron bombardment of the back of the sample holder plate. Further technical details of sample preparation, AFM and NC-AFM measurements can be found in the Supplementary Information.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Barth, C. et al. A perfectly stoichiometric and flat CeO2(111) surface on a bulk-like ceria film. Sci. Rep. 6, 21165; doi: 10.1038/srep21165 (2016).

References

Trovarelli, A. & Fornasiero, P. Catalysis by ceria and related materials. 2nd edn (Imperial College Press, London, 2013).

Gorte, R. J. Ceria in catalysis: From automotive applications to the water-gas shift reaction. AIChE J. 56, 1126–1135 (2010).

Di Monte, R. & Kašpar, J. On the role of oxygen storage in three-way catalysis. Topics Catal. 28, 47–57 (2004).

Matsumoto, S. Recent advances in automobile exhaust catalysts. Catal. Today 90, 183–190 (2004).

Paier, J., Penschke, Ch. & Sauer, J. Oxygen defects and surface chemistry of ceria: quantum chemical studies compared to experiment. Chem. Rev. 113, 3949–85 (2013).

Eck, S., Castellarin-Cudia, C., Surnev, S., Ramsey, M. G. & Netzer, F. P. Growth and thermal properties of ultrathin cerium oxide layers on Rh (111). Surf. Sci. 520, 173–185 (2002).

Lu, J.-L., Gao, H.-J., Shaikhutdinov, S. & Freund, H.-J. Morphology and defect structure of the CeO2(111) films grown on Ru(0001) as studied by scanning tunneling microscopy. Surf. Sci. 600, 5004–5010 (2006).

Grinter, D. C., Ithnin, R., Pang, Ch. L. & Thornton, G. Defect structure of ultrathin ceria films on Pt(111): Atomic views from scanning tunnelling microscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C 114, 17036–17041 (2010).

Stetsovych, V. et al. Epitaxial cubic Ce2O3 films via Ce–CeO2 interfacial reaction. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 866–871 (2013).

Luches, P., Pagliuca, F. & Valeri, S. Structural and morphological modifications of thermally reduced cerium oxide ultrathin epitaxial films on Pt(111). Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 18848–18857 (2014).

Nie, J. C., Yamasaki, H., Yamada, H., Nakagawa, Y. & Develos-Bagarinao, K. Self-assembled CeO2 buffer layers on R-cut sapphire for high-current-density YBa2Cu3O7−δ films. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 16, 768–772 (2003).

Nie, J. C. & Yamasaki, H. High density of nanodots on atomically flat CeO2 buffer layers for inducing effective vortex-pinning centers in YBa2 Cu3 O7−δ films on sapphire. Thin Solid Films 515, 2577–2581 (2006).

Flege, J.- I. et al. Ultrathin, epitaxial cerium dioxide on silicon. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 131604 (2014).

Allahgholi, A., Flege, J.-I., Thieß, S., Drube, W. & Falta, J. Oxidation-state analysis of ceria by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Chem. Phys. Chem. 16, 1083–1091 (2015).

Zoellner, M. H. et al. Stacking behavior of twin-free type-B oriented CeO2(111) films on hexagonal Pr2O3(0001)/Si(111) systems. Phys. Rev. B 85, 035302 (2012).

Niu, G. et al. Controlling the physics and chemistry of binary and ternary praseodymium and cerium oxide systems. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 4513 (2015).

Pieper, H. H. et al. Morphology and nanostructure of CeO2(111) surfaces of single crystals and Si(111) supported ceria films. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14, 15361–15368 (2012).

Olbrich, R. et al. A well-structured metastable ceria surface. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 081910 (2014).

Tani, E., Yoshimura, M. & Sōmiya, S. In Hydrothermal reactions for materials science and engineering - an overview of research in Japan (ed Sōmiya, S. ) 220–226 (Springer: Netherlands, London,, 1989).

Torbrügge, S., Cranney, M. & Reichling, M. Morphology of step structures on CeO2(111). Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 073112 (2008).

Reichling, M., Huisinga, M., Gogoll, S. & Barth, C. Degradation of the CaF2(111) surface by air exposure. Surf. Sci. 439, 181–190 (1999).

Barth, C., Claeys, C. & Henry, C. R. Surface preparation of hard ionic crystals by ultrahigh vacuum cleavage. Rev. Sci. Instr. 76, 083907 (2005).

Mullins, D. R., Overbury, S. H. & Huntley, D. R. Electron spectroscopy of single crystal and polycrystalline cerium oxide surfaces. Surf. Sci. 409, 307–319 (1998).

Hasegawa, T. et al. Epitaxial growth of CeO2(111) film on Ru(0001): Scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) and x-ray photoemission spectroscopy (XPS) study. J. Chem. Phys. 140, 044711 (2014).

Kundakovic, Lj ., Mullins, D. R. & Overbury, S. H. Adsorption and reaction of H2O and CO on oxidized and reduced Rh/CeOx(111) surfaces. Surf. Sci. 457, 51–62 (2000).

Henderson, M. A., Perkins, C. L., Engelhard, M. H., Thevuthasan, S. & Peden, C. H. F. Redox properties of water on the oxidized and reduced surfaces of CeO2(111). Surf. Sci. 526, 1–18 (2003).

Krawczyk, M., Holdynski, M., Lisowski, W., Sobczak, J. W. & Jablonski, A. Electron inelastic mean free paths in cerium dioxide. Appl. Surf. Sci. 341, 196–202 (2015).

Preisler, E. J., Marsh, O. J., Beach, R. A. & McGill, T. C. Stability of cerium oxide on silicon studied by x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 19, 1611–1618 (2001).

Wilkens, H. et al. Structural transitions of epitaxial ceria films on Si(111). Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 18589–18599 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We express our great appreciation to M. H. Zoellner, G. Niu and T. Schroeder from the institute Innovations for High Performance Microelectronics (Frankfurt/Oder, Germany) for the preparation of the samples. Stimulating discussions on ceria redox properties and XPS data analysis with V. Ganduglia-Pirovano, G. E. Murgida, P. Luches and J.-I. Flege and support from the COST Action CM1104 and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft through grant RE 1186/12-1 are gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.B. and M.R. wrote the article whereas C.B., C.L., R.O., Ph. P. and M.R. contributed to the interpretation of the data and reviewed the article. C.B. conducted the NC-AFM experiments in UHV whereas the tapping mode AFM experiments in air were done by C.B. and A.R. The XPS measurements have been performed by C.L. and Ph.P.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Barth, C., Laffon, C., Olbrich, R. et al. A perfectly stoichiometric and flat CeO2(111) surface on a bulk-like ceria film. Sci Rep 6, 21165 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep21165

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep21165

This article is cited by

-

Nanoarchitectonics of (110) directed polyethylene glycol stabilized cerium nanoparticles for UV filtering applications

Journal of Materials Science (2022)

-

Proton-assisted creation of controllable volumetric oxygen vacancies in ultrathin CeO2−x for pseudocapacitive energy storage applications

Nature Communications (2019)

-

CeO2-based nanoheterostructures with p–n and n–n heterojunction arrangements for enhancing the solar-driven photodegradation of rhodamine 6G dye

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.