Abstract

By first-principles calculations we investigate the electronic structure of tetragonal BiCoO3/BiFeO3 bilayers with different terminations. The multiferroic insulator BiCoO3 and BiFeO3 transform into metal in all of three models. Particularly, energetically favored model CoO2-BiO exhibits ferroelectric metallic properties, and external electric field enhances the ferroelectric displacements significantly. The metallic character is mainly associated to eg electrons, while t2g electrons are responsible for ferroelectric properties. Moreover, the strong hybridization between eg and O p electrons around Fermi level provides conditions to the coexistence of ferroelectric and metallic properties. These special behaviors of electrons are influenced by the interfacial electronic reconstruction with formed Bi-O electrovalent bond, which breaks OA-Fe/Co-OB coupling partially. Besides, the external electric field reverses spin polarization of Fe/Co ions efficiently, even reaching 100%.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multiferroics with ferroelectricity, ferromagnetism or ferroelasticity simultaneously have great potential applications in information storage, electronic devices and sensors1,2,3. Particularly, magneto-electric multiferroics, where the spontaneous ferroelectric polarization can be controlled by an external magnetic field or vice versa, are found in perovskite-type transition metal oxides providing bright prospect for novel spintronic devices4,5,6,7,8. Oxide heterostructures exhibit unique properties absent in the corresponding isolated parent compounds, therefore it is an effective means to study emergent physics of correlated electrons, such as, metal-insulator transition9, two-dimensional electron gas and sharp interfaces at LaAlO3/SrTiO3 interfaces10,11,12,13, orientation-dependent magnetism and so on14. Besides, recent technology advances in oxide synthesis at the atomic level make artificially designing heterostructures feasible15. We attempt to combine two perovskite-like multiferroics into bilayers aimed at inducing novel electronic and magnetic states, providing theoretical support for new multifunction devices as well. We pay attention upon Bi-based perovskite materials, whose ferroelectric properties originates from a lone pair of (6s)2 electrons16,17,18, and select tetragonal BiFeO3 (BFO) and BiCoO3 (BCO) as multiferroics candidates.

The perovskite BFO is the only known room-temperature single-phase magneto-electric multiferroic material, which is intensively studied in the last decade, with a high ferroelectric Curie temperature of 1103 K and antiferromagnetic Neel temperature of 643 K19,20,21,22,23, exhibiting weak magnetism at room temperature due to a residual moment from a canted spin structure24. Notablely, tetragonal BFO has much higher spontaneous polarization of 150 μC/cm2 and charge transfer excitations than rhombohedral phase, and gets considerable high resistance changes in ferroelectric tunnel junctions25,26,27,28,29. The resistance changes in ferroelectric tunnel junctions based on tetragonal BFO are considerably high (OFF/ON ratio >10000) among known ferroelectric tunnel junctions30. BCO has been suggested to be a promising multiferroic material, which is predicted to exhibit a giant polarization and extremely high transition temperature31,32. The ferroelectricity of BCO is found to be primarily driven by the lone-pair activity of Bi3+, and magnetism being driven by the high-spin state of Co3+ in a C-type antiferromagnetic structure below a Neel temperature of 420 K33,34. And, BFO and BCO with large spontaneous ferroelectric polarization have great potential application in electrically controllable devices35,36,37,38,39. Besides, compounding BFO with BCO is accessible experimentally in the form of epitaxial thin film40 and the BFO/BCO multiferroic solid solutions are studied theoretically41. Previous studies show that the antiferromagnetic insulator BiFeO3 can exhibit ferromagnetism in BiFeO3/La2/3Sr1/3MnO3 interface42,43 and two-dimensional electron gas in BiFeO3/SrTiO3 interface44, demonstrating that heterointerface is significant in BiFeO3-based bilayers. However, the heterostructures by constructing BiFeO3 with another multiferroic BiCoO3 may present some fantastic properties based on its multiferroic characteristics.

In this paper, we study the electronic structure of BCO/BFO bilayers with different terminations and investigate the external electric field effect on the bilayers by first-principles calculations. We find that energetically favored model CoO2-BiO exhibits ferroelectric metallic properties due to the division of eg and t2g electrons as well as eg-p hybridization. Additional, external electric field enhances the ferroelectric displacements markedly. These special behaviors of electrons are influenced by the interfacial electronic reconstruction with formed Bi-O electrovalent bond, which breaks OA-Fe/Co-OB coupling partially. Our results indicate that interfacial coupling and electric field play key roles on the novel ferroelectric metallic properties of model CoO2-BiO, which provides opportunities for developing functional nanoelectronic devices.

Calculation Details

Our first-principle calculations are performed using density functional theory (DFT) within the local spin-density approximation (LSDA), based on the projector augment wave (PAW) pseudo-potentials. The energy cutoff for plane wave basis set is 500 eV and the Brillouin zone is sampled with Γ-centered 5 × 5 × 5 and 5 × 5 × 1 k point meshes for bulk compounds and bilayers respectively, providing numerical convergence of 10−5eV. All the structures are fully relaxed until the maximum Hellmann-Feynman forces on each atom are less than 0.02 eV/Å. Aimed at getting reasonable results, we include an on-site Coulomb repulsion of U = 6 eV for Co 3d states45, and U = 4.5 eV for Fe 3d states46,47, which are sufficient to describe the related bulk properties.

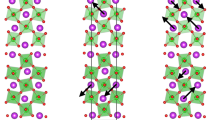

Tetragonal phase of the multiferroic BFO used in this work has a perovskite-type structure with a lattice constant of a = 3.770 Å and c/a = 1.233 in space group P4 mm47. The primitive cell of tetragonal BFO contains one molecule with one Bi atom located at (0.0, 0.0, 0.0), one Fe atom at (0.5, 0.5, 0.439), one axial OA atom at (0.5, 0.5, −0.170) in BiO layer and two equatorial OB atoms at (0.0, 0.5, 0.294) and (0.5, 0.0, 0.294) in FeO2 layer. The magnetic character of BFO is G-type where the Fe atoms are coupled ferromagnetically within the (111) planes and antiferromagnetically between adjacent planes. Bulk BCO is an antiferromagnetic insulator of C-type which is the most stable magnetic order in BCO48, where Co ions are aligned antiferromagnetically in the xy plane and ferromagnetically along the z axis, with a lattice constant of a = 3.729 Å and c/a = 1.267 in space group P4 mm45. The used experiment value of atomic coordinates in BCO are Bi (0.0, 0.0, 0.0), Co (0.5, 0.5, 0.5669), one axial OA (0.5, 0.5, 0.2034) and two equatorial OB (0.5, 0.0, 0.73)33. Bi ions locate in the corner sites, yet Fe (or Co) ions and O ions which ought to occupy the body and face centered sites respectively move from center sites in the z direction owing to ferroelectric spontaneous polarization. In the supercells of BCO/BFO studied here, a 28 Å vacuum space in z direction is used to separate the interaction between periodic images and the supercells are built by placing five BCO atomic layers on the top of five BFO atomic layers within p( ) periodicity giving altering layers of Bi2O2 and Co2O4 (Fe2O4) along the [001] direction. In experiments, the thin films must present one surface that is exposed in the vacuum, even though the sample is a multilayered structure. Hence, the bilayer geometry with vacuum should be calculated. Meanwhile, the difference of optimized geometry and atomic position can affect the multiferroics of the sample. In superlattice structure, there are two interfaces which might influence the relaxation of the atoms, so that each atomic position should be different from the case of bilayer with vacuum. Meanwhile, in order to study the effect of external electric field, the bilayer with vacuum is necessary. We apply external electric field for the bilayers in z direction and switch on the potential correction mode. The calculated in-plane lattice mismatch between BFO(001) and BCO(001) is 1.1%, indicating a good lattice match. We set up three BCO/BFO bilayers with different terminations to investigate the interfacial properties, as shown in Fig. 1(a–c).

) periodicity giving altering layers of Bi2O2 and Co2O4 (Fe2O4) along the [001] direction. In experiments, the thin films must present one surface that is exposed in the vacuum, even though the sample is a multilayered structure. Hence, the bilayer geometry with vacuum should be calculated. Meanwhile, the difference of optimized geometry and atomic position can affect the multiferroics of the sample. In superlattice structure, there are two interfaces which might influence the relaxation of the atoms, so that each atomic position should be different from the case of bilayer with vacuum. Meanwhile, in order to study the effect of external electric field, the bilayer with vacuum is necessary. We apply external electric field for the bilayers in z direction and switch on the potential correction mode. The calculated in-plane lattice mismatch between BFO(001) and BCO(001) is 1.1%, indicating a good lattice match. We set up three BCO/BFO bilayers with different terminations to investigate the interfacial properties, as shown in Fig. 1(a–c).

(a–c) side views of BCO/BFO bilayers for model CoO2-BiO, CoO2-FeO2 and BiO-FeO2 respectively. (d–f) charge density difference of model CoO2-BiO (isosurface value 0.008 e/Å3) in E = 0, 6 and 10 mV/Å respectively, (g–i) for model CoO2-FeO2 (isosurface value 0.003 e/Å3)and (j–l) for model BiO-FeO2 (isosurface value 0.008 e/Å3). The red spheres stand for O, dark yellow for Fe, dark blue for Co and purple for Bi. The yellow and blue isosurfaces represent accumulation and depletion of electrons, respectively.

The stable pattern is determined by calculating the work of separation, i.e., the cohesive energy between BCO and BFO,  , where EBCO/BFO is the total energy of the bilayers, EBCO and EBFO represent the energies of the same supercell containing either the BCO or BFO parts (i.e., we keep the equilibrium structure obtained for the bilayers). For illustrating the nature of the charge transfer at BCO/BFO interface, we calculate the charge density difference by subtracting the charge densities of isolated BFO and BCO parts from the charge density of bilayers as shown in Fig. 1(d–l). The electronic structures of isolated BFO and BCO are calculated by freezing the atoms of the respective component at the supercell positions.

, where EBCO/BFO is the total energy of the bilayers, EBCO and EBFO represent the energies of the same supercell containing either the BCO or BFO parts (i.e., we keep the equilibrium structure obtained for the bilayers). For illustrating the nature of the charge transfer at BCO/BFO interface, we calculate the charge density difference by subtracting the charge densities of isolated BFO and BCO parts from the charge density of bilayers as shown in Fig. 1(d–l). The electronic structures of isolated BFO and BCO are calculated by freezing the atoms of the respective component at the supercell positions.

Results and Discussion

First, we analyze the total and projected densities of states (DOS) of fully relaxed bulk BFO and BCO shown in Fig. 2. For BFO, the charge transfer gap is determined by the filled oxygen 2p band and the unoccupied 3d band of Fe, and the calculated band gap of 1.93 eV is in good agreement with previous calculations49, but inconsistent with the experimental value of 3.10 eV50, as a result of using the LSDA approximation. The Fe spins are antiparallel and the corresponding DOS is symmetrical, so we only show one. The calculated Fe magnetic moments are ±4.107 μB per atom. For BCO, the calculated total DOS is similar with previous calculations45, and the Co ions are in high-spin state which is consistent with the experimental result33, as shown in Fig. 2(a,d). The spin-up and spin-down band structures are completely compatible, so we only show spin-up structure in Fig. 2(e). We find that the strong correlated effect of Co 3d is well described with a band gap of 1.52 eV and the Co magnetic moments are ±3.035 μB per atom, which are in good agreement with the experimental values of 1.7 eV and 3.24 μB33,51. These bulk results reveal that the used parameters in the present work are reasonable.

We carry out the electronic band structures of three models and separate out the BCO’s contribution to demonstrate the changes of the electronic states in BCO by comparing with bulk BCO states in same path, as shown in Fig. 3. Obviously, both BCO and BFO transforms into metal in all of three interfacial models and BCO undergoes a dramatic change, revealing that interfacial compound probably is an efficient method to explore emergent physics as well. The strong interfacial effect is also reflected by the remarkable accumulation and depletion of electrons at interfaces, as shown in Fig. 1(d–l). Bi and O ions combine with each other in the form of electrovalent bond with Bi depleting and O accumulating electrons in the interfacial regions of model CoO2-BiO and BiO-FeO2, see Fig. 2(d,j). For model CoO2-FeO2, apparent accumulation of electrons between Co and Fe occurs at the interfacial regions revealing that Co and Fe ions combine via metallic bond we propose, as shown in Fig. 2(g). The calculated cohesive energies demonstrate that model CoO2-BiO is the most stable structure with a considerably large value of 11.474 eV and model CoO2-FeO2 is very unstable with a negative value, as listed in Table 1, which is reasonable since the interfaces in model CoO2-BiO and BiO-FeO2 are similar with the structures of bulk BCO and BFO, while model CoO2-FeO2 totally not.

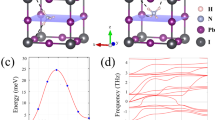

We further analyze the geometric structure of three models and the Bi-O, Fe-O and Co-O polar displacements of three models in one layer along [001] direction are calculated by subtracting the position of O ions. The black lines in Fig. 4 indicate that the displacements of model CoO2-BiO is larger than the other two models and we list the average values in Table 1. It is obvious that the displacements in model CoO2-BiO is almost 50% larger than model CoO2-FeO2 and model BiO-FeO2 and nearly three quarters of correspond bulks. Therefore, model CoO2-BiO exhibit metallic properties with remarkable ferroelectric structures since tetragonal BCO and BFO are typical displacive ferroelectrics originating from relative displacement of positive and negative ions27,48,52,53. To further investigate its ferroelectric properties, we add an electric field to all of three bilayers considering the strong electric field effect on ferroelectrics owing to the spontaneous polarization. Based on the experimental study on bulk52,54, we add the electric field of 6 and 10 mV/Å (i.e., 600 and 1000 kV/cm) respectively and calculated the relative displacements of positive and negative ions in same layer along z axis, as shown in Fig. 4. We find that the polarization displacements in model CoO2-FeO2 and model BiO-FeO2 with electric field (see red and blue lines) are close to the situation without electric field (see black lines) shown in Fig. 4(b,c), but the polarization shifts in model CoO2-BiO are enhanced greatly on the condition of applied electric field, particularly at the interfacial regions as shown in Fig. 4(a). This result further confirms the ferroelectric metallic properties of model CoO2-BiO and demonstrates that external electric field can modulate the ferroelectric polarization. Figure 1(d) reveals the strong interfacial coupling by Bi-O electrovalent bonds in the interfacial regions of model CoO2-BiO, and we further notice that the interfacial Bi-O bonds exist even in applied electric field, as shown in Fig. 1(e,f). This short-range pair interaction makes the ferroelectric polarization properties of bulks preserved in bilayers and lowers the electrostatic energy further stabilize the bilayers structure.

The change of Bi-O and B-O polar displacements in each layer along [001] direction in model (a) CoO2-BiO, (b) CoO2-FeO2 and (c) BiO-FeO2 due to different values of external electric field, B = Co/Fe. Open square symbols represent Bi-O displacements, and solid square symbols represent B-O displacements.

On the other hand, the structure of models CoO2-BiO and BiO-FeO2 contains two asymmetry surfaces and might be as polar as LaAlO3/SrTiO3 interface within a large “internal” electric field9,55, which automatically gives rise to the metallicity of the system. We check the same asymmetry geometry in pure BFO and BCO, which possesses the form (BiO-MO2)n within 15 Å vacuum space in z direction (M = Fe/Co, n = 2, 3, 4). The calculated band structures indicate that such pure BFO is insulating when n = 2/3 but exhibits metallic in n = 4, while the pure BCO is metallic and not affected by n. Hence, the asymmetry structure is important for the metallic characters in CoO2-BiO model. Furthermore, such pure metallic properties in BFO and BCO are distinguished from the metallic characters in model CoO2-BiO. Firstly, both uppermost valence band (UVB) and lowest conduction band (LCB) approach the Fermi level in (BiO-FeO2)4, while the LCB of isolated BFO in model CoO2-BiO is far away from the Fermi level (see Fig. 3a). Secondly, the UVB in pure BCO overlaps with the Fermi level heavily, while the UVB of isolated BiCoO3 in CoO2-BiO model only approach the Fermi level (see Fig. 3a). It is obvious that the strong interfacial couplings have a great effect on the metallic characters in CoO2-BiO model.

Next, we analyze the electronic DOS distribution of ions in the interfacial regions of model CoO2-BiO in detail shown in Fig. 5. We find that, for BCO, I-Co d electrons hybridize with II-O p electrons distinctly but interact weakly with I-O p electrons in the energy range from −3 eV to Fermi level (EF) as indicated in Fig. 5(a). Similarly, for BFO, II-Fe d electrons hybridize obviously with II-O p electrons while lightly with I-O p electrons in the energy window from −1.2 to −0.3 eV as shown in Fig. 5(b). The label “I-Co” represents the Co ions in layer I as shown in Fig. 1(a), and this kind of definition is used in the whole letter. For bulk BCO and BFO, Fe/Co ions hybridize with OA and OB, along with clear O alignment as shown in Fig. 2(b,c). For model CoO2-BiO, the interfacial Bi-O bonds make I-O p electrons in BFO and BCO change dramatically and break the balance of OA-Fe/Co-OB partially, which further influences the metallic properties of bilayers with retained ferroelectric properties. Then, we analyze the Fe/Co DOS in each layer in different on the condition of electric field or not, as shown in Fig. 6. The Fe electronic distribution varies gently as indicated by Fig. 6(a–c), while Co ions change heavily shown in Fig. 6(d–f). We define spin polarization  in terms of the total DOS in the spin-up N↑ and spin-down N↓ channels respectively, and find that the spin polarization of I-Co is reversed from 70% to −89% on the condition of E = 6 mV/Å by comparing Fig. 6(d) with Fig. 6(e). Besides, the spin polarization of III-Co and V-Co are reversed from 49% to −82% and 54% to −62% respectively on the condition of E = 10 mV/Å according to Fig. 6(d,f). The apparent positive-negative spin polarization reverse in Co ions demonstrates that electric field not only can be used to induce magnetic moments via magneto-electric effect as previous report2, but also can reverse spin polarization. The Fe/Co magnetic moments are listed in Table 2, which are influenced heavily by interfacial effect and electric field. The numbers of Fe/Co magnetic moments in same layer are equal but with different signs, so we only list the positive numbers in Table 2. In addition, the Co magnetic moments are changed easily, which is reasonable since the Co ions possess flexible possibilities of high, intermediate and low spin states. The electronic rearrangements of Co caused by interfacial coupling are also reflected by charge density difference since electrons with different orbital contours increase or decrease, shown in Fig. 1(d–l).

in terms of the total DOS in the spin-up N↑ and spin-down N↓ channels respectively, and find that the spin polarization of I-Co is reversed from 70% to −89% on the condition of E = 6 mV/Å by comparing Fig. 6(d) with Fig. 6(e). Besides, the spin polarization of III-Co and V-Co are reversed from 49% to −82% and 54% to −62% respectively on the condition of E = 10 mV/Å according to Fig. 6(d,f). The apparent positive-negative spin polarization reverse in Co ions demonstrates that electric field not only can be used to induce magnetic moments via magneto-electric effect as previous report2, but also can reverse spin polarization. The Fe/Co magnetic moments are listed in Table 2, which are influenced heavily by interfacial effect and electric field. The numbers of Fe/Co magnetic moments in same layer are equal but with different signs, so we only list the positive numbers in Table 2. In addition, the Co magnetic moments are changed easily, which is reasonable since the Co ions possess flexible possibilities of high, intermediate and low spin states. The electronic rearrangements of Co caused by interfacial coupling are also reflected by charge density difference since electrons with different orbital contours increase or decrease, shown in Fig. 1(d–l).

Although it is widely believed that metals cannot exhibit ferroelectricity since the static internal electric fields are screened by conduction electrons56, the ferroelectric metal is theoretically proposed by Anderson and Blount in 196557. Recently LiOsO3 is identified as the first typical example58, and the microscopic mechanism for the ferroelectric-like structural transition in a metal are investigate widely59,60. The Mott multiferroic based on LiOsO3 is predicted by compounding with LiNbO3 as well61. However, in our model CoO2-BiO, the ferroelectrics are transformed into metal from insulator via interfacial coupling, which is opposite the LiOsO3-type metal into ferroelectric transition. The itinerant d electrons can screen the electric fields and inhibit the electrostatic forces, so we analyze the d electron states of Fe/Co ions in each layer of model CoO2-BiO on purpose as shown in Fig. 7. We find that the metallic property is associated to the electrons in eg orbitals (i.e.,  and

and  ), and these electrons hybridize with O p electrons around EF according to Fig. 5. However, the electrons in t2g orbitals (i.e., dxy, dxz, and dyz) have no contribution to the metallic character, which are responsible for the ferroelectric properties as shown in Figs 2(d) and 7. Therefore, although the specific eg electrons exhibit metallic property, they simultaneously hybridize with O p electrons, which makes ferroelectric and metallic features coexist. And we argue that this special electron occupation is tightly associated with the interfacial coupling as mentioned above.

), and these electrons hybridize with O p electrons around EF according to Fig. 5. However, the electrons in t2g orbitals (i.e., dxy, dxz, and dyz) have no contribution to the metallic character, which are responsible for the ferroelectric properties as shown in Figs 2(d) and 7. Therefore, although the specific eg electrons exhibit metallic property, they simultaneously hybridize with O p electrons, which makes ferroelectric and metallic features coexist. And we argue that this special electron occupation is tightly associated with the interfacial coupling as mentioned above.

On the other hand, the ferroelectric displacements are not sensitive to external electric field in model BiO-FeO2 as shown in Fig. 4(c), and we believe that the different behavior of models CoO2-BiO and BiO-FeO2 is a result of termination effect. It is also found in model BiO-FeO2 that the electric field reverses spin polarization of Fe/Co ions. Figure 8(d–f) indicate that the spin polarization of IV-Co are reversed from −73% to 100% upon E = 6 and 10 mV/Å, While V-Fe are reversed from −100% to 53% upon E = 10 mV/Å according to Fig. 8(a,c). These results show that electric field can not only reverse the positive and negative of spin polarization, but also reach a considerable value even 100%. In addition, the synthesis technology of oxides has beem improved significantly, such as MBE MOCVD, etc., which can fabricate high-quality epitaxial films and heterostructures. We take the La0.7Sr0.3MnO3/BiFeO3 structures as an example. For the growth of La0.7Sr0.3O terminated La0.7Sr0.3MnO3 film, Yu et al. modify the SrTiO3 substrate from TiO2 termination to SrO termination62. To achieve this, a very thin layer (2.5 unit cells) of SrRuO3 was grown on SrTiO3, or growing one monolayer of SrO on the TiO2 terminated SrTiO3 substrate. And Kim et al. also fabricated the BiFeO3-MnO2-terminated and BiFeO3-(La,Sr)O-terminated La0.7Sr0.3MnO3 structures in similar method63. Therefore, the energetically unfavored termination can be achieved by inserting specific monolayer in the stable termination. The prediction of ferroelectric metallic characteristics in BiFeO3/BiCoO3 bilayers is meaningful for the expertimental research, which can provide opportunities for developing novel functional electronic devices.

Conclusion

In summary, we investigate the electronic structure of BCO/BFO(001) bilayers with different terminations based on first-principles calculations. The multiferroic insulator BCO and BFO transform into metal in all of three models. Particularly, energetically favored model CoO2-BiO exhibits ferroelectric metallic properties and external electric field enhances the ferroelectric displacements markedly. The metallic character is mainly associated to the eg electrons of Fe/Co ions and these electrons simultaneously hybridize with O p electrons around EF, yet the t2g electrons are responsible for ferroelectric properties. Therefore, the division of eg and t2g electrons as well as eg-p hybridization provide conditions to the coexistence of ferroelectric and metallic properties. These special behaviors of electrons are influenced by the interfacial electronic reconstruction with formed Bi-O electrovalent bond, which breaks OA-Fe/Co-OB coupling partially. Besides, strong interfacial coupling changes the Fe/Co magnetic moments and external electric field reverses spin polarization of Fe/Co ions efficiently, reaching a maximum of 100%. Our results demonstrate that interfacial coupling and electric field play key roles on the novel ferroelectric metallic properties of model CoO2-BiO, which provides opportunities for developing functional nanoelectronic devices. We hope that our theoretical prediction on the ferroelectric metallic properties and corresponding electric field effect can stimulate further experimental study.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Yin, L. et al. Ferroelectric Metal in Tetragonal BiCoO3/BiFeO3 Bilayers and Its Electric Field Effect. Sci. Rep. 6, 20591; doi: 10.1038/srep20591 (2016).

References

Ramesh, R. & Spaldin, N. A. Multiferroics: progress and prospects in thin films. Nat. Mater. 6, 21–9 (2007).

Tokura, Y. Multiferroics as quantum electromagnets. Science 312, 1481–1482 (2006).

Fiebig, M. Revival of the magnetoelectric effect. J. Phys. D 38, R123–R148 (2005).

Gibert, M., Zubko, P., Scherwitzl, R. Iniguez, J. & Triscone, J. M. Exchange bias in LaNiO3-LaMnO3 superlattices. Nat. Mater. 11, 195–198 (2012).

Hur, N. et al. Electric polarization reversal and memory in a multiferroic material induced by magnetic fields. Nature 429, 389–392 (2004).

Eerenstein, W., Mathur, N. D. & Scott, J. F. Multiferroic and magnetoelectric materials. Nature (London) 442, 759–65 (2006).

Spaldin, N. A. & Fiebig, M. The renaissance of magnetoelectric multiferroics. Science 309, 391–392 (2005).

Cheong, S. W. & Mostovoy, M. Multiferroics: a magnetic twist for ferroelectricity. Nat. Mater. 6, 13–20 (2007).

Ohtomo, A. & Hwang, H. Y. A high-mobility electron gas at the LaAlO3/SrTiO3 heterointerface. Nature 427, 423–426 (2004).

Cossu, F., Jilili, J. & Schwingenschlögl, U. 2D electron gas with 100% spin-polarization in the (LaMnO3)2/(SrTiO3)2 superlattice under uniaxial strain. Adv. Mater. 1, 1400057 (2014).

Jeong, H. Y. & Lee, J. H. Critical thickness for the two-dimensional electron gas in LaTiO3/SrTiO3 superlattice. Phys. Rev. B 88, 155111 (2013).

Zhang, Z., Wu, P., Chen, L. & Wang, J. L. First-principles prediction of a two dimensional electron gas at the BiFeO3/SrTiO3 interface. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 062902 (2011).

Nakagawa, N., Hwang, H. Y. & Muller, D. A. Why some interfaces cannot be sharp. Nat. Mater. 5, 204–209 (2006).

Dong, S. & Dagotto, E. Quantum confinement induced magnetism in LaNiO3-LaMnO3 superlattice. Phys. Rev. B 87, 195116 (2013).

Hwang, H. Y. et al. Emergent phenomena at oxide interfaces. Nat. Mater. 11, 103–113 (2012).

Cohen, R. E. Origin of ferroelectricity in perovskite oxides. Nature 358, 136–138 (1992).

Baettig, P., Schelle, C. F., LeSar, R., Waghmare, U. V. & Spaldin, N. A. Theoretical prediction of new high-performance lead-free piezoelectrics. Chem. Mater. 17, 1376–1380 (2005).

Iniguez, J., Vanderbilt, D. & Bellaiche, L. First-principles study of (BiScO3)1−x -(PbTiO3) x piezoelectric alloys. Phys. Rev. B 67, 224107 (2003).

Catalan, G. & Scott, J. F. Physics and applications of bismuth ferrite. Adv. Mater. 21, 2463–2485 (2009).

Kiselev, S. V., Ozerov, R. P. & Zhdanov, G. S. Detection of magnetic order in ferroelectric BiFeO3 by neutron diffraction. Sov. Phys. Dokl. 7, 742–744 (1963).

Neaton, J. B., Ederer, C., Waghmare, U. V., Spaldin, N. A. & Rabe, K. M. First-principles study of spontaneous polarization in multiferroic BiFeO3 . Phys. Rev. B 71, 014113 (2005).

Ederer, C. & Spaldin, N. A. Weak ferromagnetism and magnetoelectric coupling in bismuth ferrit. Phys. Rev. B 71, 060401R (2005).

Lebeugle, D. et al. Electric-field-induced spin flop in BiFeO3 single crystals at room temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 227602 (2008).

Smolenskii, G. A. & Chupis, I. Ferroelectromagnets. Sov. Phys. Usp. 25, 475–493 (1982).

Zeches, R. J. et al. A strain-driven morphotropic phase boundary in BiFeO3 . Science 326, 977–80 (2009).

Damodaran, A. R. et al. Nanoscale structure and mechanism for enhanced electromechanical response of highly strained BiFeO3 thin films. Adv. Mater. 23, 3170–3175 (2011).

Hatt, A. J., Spaldin, N. A. & Ederer, C. Strain-induced isosymmetric phase transition in BiFeO3 . Phys. Rev. B 81, 054109 (2010).

Martin, L. W. et al. Multiferroics and magnetoelectrics: thin films and nanostructures. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 20, 434220 (2008).

Chen, P. et al. Optical properties of quasi-tetragonal BiFeO3 thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 131907 (2010).

Yamada, H. et al. Giant electroresistance of super-tetragonal BiFeO3-based ferroelectric tunnel junctions. ACS Nano 7, 5385–5390 (2013).

Yoshitaka, U., Tatsuya, S., Fumiyuki, I. & Tamio, O. First-principles predictions of giant electric polarization. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 44, 7130–7133 (2005).

Oka, K. et al. Magnetic ground-state of perovskite PbVO3 with large tetragonal distortion. Inorg. Chem. 47, 7355–7359 (2008).

Belik, A. A. et al. Neutron powder diffraction study on the crystal and magnetic structures of BiCoO3 . Chem. Mater. 18, 798–803 (2006).

Das, T. & Saha-Dasgupta, T. Spin-state transition in unstrained and strained ultra-thin BiCoO3 films. Dalton Trans. 44, 10882–10887 (2015).

Wang, J. et al. Epitaxial BiFeO3 multiferroic thin film heterostructures. Science 299, 1719–1722 (2003).

Wang, J. et al. Response to comment on “epitaxial BiFeO3 multiferroic thin film heterostructures”. Science 307, 1203b (2005).

Bea, H. et al. Investigation on the origin of the magnetic moment of BiFeO3 thin films by advanced x-ray characterizations. Phys. Rev. B 74, 020101R (2006).

Bea, H. et al. Influence of parasitic phases on the properties of BiFeO3 epitaxial thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 87, 072508 (2005).

Rana, D. S. et al. Thickness dependence of the structure and magnetization of BiFeO3 thin films on (LaAlO3)0.3(Sr2AlTaO6)0.7 (001) substrate. Phys. Rev. B 75, 060405R (2007).

Shintaro, Y. et al. Crystal structure and electrical properties of {100} oriented epitaxial BiCoO3-BiFeO3 films grown by metalorganic chemical vapor deposition. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 47, 7582 (2008).

Dieguez, O. & Iniguez, J. First-principles investigation of morphotropic transitions and phase-change functional responses in BiFeO3-BiCoO3 multiferroic solid solutions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 057601 (2011).

Yu, P. et al. Interface ferromagnetism and orbital reconstruction in BiFeO3-La0.7Sr0.3MnO3 heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 027201 (2010).

Wu, S. M. et al. Reversible electric control of exchange bias in a multiferroic field-effect device. Nat. Mater. 9, 756–761 (2010).

Chen, C. L. et al. Two-dimensional electron gas at the Ti-diffused BiFeO3/SrTiO3 interface. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 031601 (2015).

Cai, M. Q. et al. First-principles study of structural, electronic, and multiferroic properties in BiCoO3 . J. Chem. Phys. 126, 154708 (2007).

Feng, N., Mi, W. B., Wang, X. C. & Bai, H. L. The magnetism of Fe4N/oxides (MgO, BaTiO3, BiFeO3) interfaces from first-principles calculations. RSC Adv. 4, 48848 (2014).

Ricinschi, D., Yun, K. Y. & Okuyama, M. A mechanism for the 150 μC cm−2 polarization of BiFeO3 films based on first-principles calculations and new structural data. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 18, L97–L105 (2006).

Sudayama, T. et al. Co-O-O-Co superexchange pathways enhanced by small charge-transfer energy in multiferroic BiCoO3 . Phys. Rev. B 83, 235105 (2011).

Yang, H., Jin, C., Mi, W. B., Bai, H. L. & Chen, G. F. Electronic and magnetic structure of Fe3O4/BiFeO3 multiferroic superlattices: first principles calculations. J. Appl. Phys. 112, 063925 (2012).

Himcinschi, C. et al. Optical properties of epitaxial BiFeO3 thin films grown on LaAlO3 . Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 012908 (2015).

McLeod, J. A. et al. Electronic structure of BiMO3 multiferroics and related oxides. Phys. Rev. B 81, 144103 (2010).

Zhang, J. X. et al. Microscopic origin of the giant ferroelectric polarization in tetragonal-like BiFeO3 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 147602 (2011).

Jia, T. et al. Ab initio study of the giant ferroelectric distortion and pressure-induced spin-state transition in BiCoO3 . Phys. Rev. B 83, 174433 (2011).

Yun, K. Y., Ricinschi, D., Kanashima, T., Noda, M. & Okuyama, M. Giant ferroelectric polarization beyond 150 μC/cm2 in BiFeO3 thin film. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 43, L647 (2004).

Weston, L., Cui, X. Y., Ringer, S. P. & Stampfl, C. Density-functional prediction of a surface magnetic phase in SrTiO3/LaAlO3 heterostructures induced by Al vacancies. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 186401 (2014).

Lines, M. E. & Glass, A. M. Principles and applications of ferroelectrics and related materials. Oxford Univ. Press (2001).

Anderson, P. W. & Blount, E. I. Symmetry considerations on martensitic transformations: “ferroelectric” metals? Phys. Rev. Lett. 14, 217–219 (1965).

Shi, Y. et al. A ferroelectric-like structural transition in a metal. Nature Mater. 12, 1024–7 (2013).

Giovannetti, G. & Capone, M. Dual nature of the ferroelectric and metallic state inLiOsO3 . Phys. Rev. B 90, 195113 (2014).

Xiang, H. J. Origin of polar distortion in LiNbO3-type “ferroelectric” metals: role of A-site instability and short-range interactions. Phys. Rev. B 90, 094108 (2014).

Puggioni, D., Giovannetti, G., Capone, M. & Rondinelli, J. M. Design of a Mott multiferroic from a nonmagnetic polar metal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 087202 (2015).

Yu, P. et al. Interface control of bulk ferroelectric polarization. PNAS 109, 9710–9715 (2012).

Kim, Y. M. et al. Interplay of octahedral tilts and polar order in BiFeO3 films. Adv. Mater. 25, 2497–2504 (2013).

Kimura, T. et al. Magnetic control of ferroelectric polarization. Nature 426, 55–58 (2003).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51171126, 11434006), Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (NCET-13-0409). It is also supported by High Performance Computing Center of Tianjin University, China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors designed the outline of the manuscript. L.Y. and W.B.M. wrote the main text; X.C.W. contributed detailed discussions and revisions; All the authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Yin, L., Mi, W. & Wang, X. Ferroelectric Metal in Tetragonal BiCoO3/BiFeO3 Bilayers and Its Electric Field Effect. Sci Rep 6, 20591 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep20591

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep20591

This article is cited by

-

Interfacial effect and strain on the electrical and magnetic properties of SrRuO3/NdNiO3 bilayers with 3D island surface layer

Applied Physics A (2022)

-

Thickness Control of the Spin-Polarized Two-Dimensional Electron Gas in LaAlO3/BaTiO3 Superlattices

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Surface modification and enhanced multiferroic behavior of BiFe0.25Cr0.75O3 films with different thickness over Pt(111)/Ti/SiO2/Si substrate

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.