Abstract

Leaf wax δDn-alkane values have shown to differ significantly among plant life forms (e.g., among grasses, shrubs and trees) in higher plants. However, the underlying causes for the differences in leaf wax δDn-alkane values among different plant life forms remain poorly understood. In this study, we observed that leaf wax δDn-alkane values between major high plant lineages (eudicots versus monocots) differed significantly under the same environmental conditions. Such a difference primarily inherited from different hydrogen biosynthetic fractionations (εwax-lw). Based upon a reanalysis of the available leaf wax δDn-alkane dataset from modern plants in the Northern Hemisphere, we discovered that the apparent hydrogen fractionation factor (εwax-p) between leaf wax δDn-alkane values of major angiosperm lineages and precipitation δD values exhibited distinguishable distribution patterns at a global scale, with an average of −140‰ for monocotyledonous species, −107‰ for dicotyledonous species. Additionally, variations of leaf wax δDn-alkane values and the εwax-p values in gymnosperms are similar to those of dicotyledonous species. Therefore, the data let us believe that biological factors inherited from plant taxonomies have a significant effect on controlling leaf wax δDn-alkane values in higher plants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Analytical advances in compound-specific stable hydrogen isotopic analysis have facilitated the use of n-alkyl lipids as the biomolecule of choice for the reconstruction of paleoenvironment. Long chain n-alkanes, major components of terrestrial plant leaf waxes1, are resistant to microbial degradation2, thus their molecular integrity and original isotopic compositions are well preserved over the geological timescale3. Leaf wax n-alkanes are also widely distributed in both terrestrial and marine sediments4,5, making them common biomarkers for the reconstruction of paleoclimate and paleohydrology6,7,8,9,10,11.

Previous studies have shown that leaf wax δDn-alkane values in modern plants or sediments are closely correlated to precipitation δD12,13,14,15,16,17. However, grown under the same environmental condition with the use of the same precipitation water, different plants exhibit various δDn-alkane values in their leaf wax n-alkanes. Liu et al.15 explained the difference as an effect of plant ecology and proposed that plant life forms (e.g., grasses, shrubs and trees) have a major influence on leaf wax δDn-alkane values. They reported a global database (n = 233) of modern leaf wax δDn-alkane values that displayed distinguished distribution patterns between woody plants (shrubs and trees) and herbaceous plants (including grasses, herbs, forbs etc.), with herbaceous plants having D-depleted by 30–50‰ relative to woody plants16. Subsequently, similar results among a variety of plant life forms such as trees, shrubs, grasses, herbs, forbs, vines, ferns and aquatic plants, were observed in specific sites in middle latitudes in North America18, at high latitudes19, as well as at the global scale based upon a larger database (n = 300)10.

However, a critical question remains unanswered: Why the differences in leaf wax δDn-alkane values among plant life forms occurred and more specifically, what is the underlying cause for the observed differences in leaf wax δDn-alkane values among different plant life forms? Liu et al.15 considered that the different source water utilized by plants might result in a greater D-enrichment in woody plants, which have more extensive root systems to tap into deeper D-enriched soil water. Hou et al.18 suggested that different abilities of evapotranspiration might be an important factor leading to less negative leaf wax δDn-alkane values in woody plants relative to grasses. Other studies attributed the difference to other environment factors such as temperature, relative humidity and light etc.14,18,20,21. Nevertheless, it has been proposed that the variability in lipid δD values is controlled by both environmental and biological factors22. Yakir and DeNiro23 implied that biosynthetic fractionation during the lipid formation remained to be constant for specific species and similar conclusion was also reached across different plant groups24,25,26. However, Kahmen et al.27,28 recently found that biosynthetic fractionation may vary up to 60‰ among different species.

Therefore, to date it is not clear whether leaf wax δDn-alkane values from modern plants were really related to plant taxonomy or simply affected by different environmental factors surrounding these individual plants. Answers to these above questions are not only critical to better understanding hydrogen fractionations in higher plants, but also have broader implications for the applications of leaf wax δDn-alkane values as a proxy for studies of paleoclimate and paleohydrology.

The majority of previous studies have demonstrated that leaf water δ18O values exhibited spatial isotopic gradients inside leaf blades29,30,31,32,33,34, although few study observed spatial gradients of leaf water δD values. Moreover, previous studies on δDn-alkane of leaf waxes have all been conducted on whole leaf samples10,15,16,18, with only one exception to focus on spatial variation of leaf wax δDn-alkane values of Miscanthus sinensis, a monocotyledonous species35. Here we sampled modern higher plants in Northwestern China to further investigate the effect of different plant taxonomies on leaf wax δDn-alkane values. In order to explore the difference in leaf wax δDn-alkane values among different plant taxonomic lineages, we analyzed the relationship between leaf water δD values and corresponding leaf wax δDn-alkane values both at the whole leaf and the segmented leaf scales.

Various plants including different major plant taxonomic lineages (e.g., eudicots, monocots, gymnosperms etc.) were sampled at each site under the same environmental condition, thus with the same hydrogen source. We investigated dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous leaf blades based on their veinal structures, with monocotyledonous leaves having parallel veins whereas dicotyledonous leaves primarily having reticulate veins29. We also recompiled and reanalyzed published modern leaf wax δDn-alkane data to date from various geographic locations in the Northern Hemisphere to investigate different patterns of hydrogen isotope fractionations during leaf wax biosynthesis among plant taxonomic lineages in higher plants.

Results

In general, leaf wax δDn-alkane values in woody plants were more D-enriched than those in herbaceous plants (e.g., grasses, herbs, forbs, etc.), consistent with previous results15,16. There were relatively significant differences in leaf wax δDn-alkane values between woody plants (shrubs and trees) and herbaceous plants (e.g., grasses, herbs, forbs, etc.) in Lantian and Xi’an36. However, some herbs and forbs obviously possessed higher δDn-alkane values in leaf wax, reaching values similar to those of woody plants in the Heshui County (Supplementary Fig. S2). If we regrouped these plants according to two major plant taxonomic lineages, eudicots and monocots, we discovered that there were more distinct differences in leaf wax δDn-alkane values between dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous species, with monocotyledonous D-depleted relative to dicotyledonous species in above three sites (Fig. 1). Leaf wax δDn-alkane values of monocotyledonous species ranged from −171‰ to −239‰ with an average of −198‰, whereas those of dicotyledonous species exhibited a range from −133‰ to −197‰, with an average of −164% in the Heshui County (Supplementary Table S1), similar results of an average of −195‰ (monocots) and −163% (eudicots) in Xi’an and Lantian36.

Previous studies have implied non-woody plants (grasses, herbs, forbs, vines and some aquatic plants etc.) as grasses10,15,16. In this study, based on our expanded database (n = 503), we regrouped the available modern leaf wax δDn-alkane data based upon dicotyledonous (including all woody plants of both shrubs and trees, as well as some herbs and forbs) and monocotyledonous species (grasses). Interestingly, dicotyledonous species apparently possessed more positive δDn-alkane values than monocotyledonous grasses. One-way ANOVA test showed that the average δDn-alkane values of leaf wax differed significantly between these two groups (P < 0.001) and that the average δDn-alkane values of monocotyledonous grasses differ significantly from those of eudicot woody plants (P < 0.001; Table 1). However, we found no significant difference in leaf wax δDn-alkane values between dicotyledonous species and woody plants (P = 0.317; Table 1) nor between shrubs and trees (P = 0.897)15. Moreover, leaf wax δDn-alkane values of monocotyledonous species ranged from −148‰ to −301‰, with an average of −202‰, whereas leaf wax δDn−alkane values of dicotyledonous species varied from −94‰ to −251‰, with an average of −165‰ (Table 1). Furthermore, leaf wax δDn−alkane values in gymnosperms varied from −103‰ to −201‰, with an average of −152‰. Importantly, the εwax-p values ranged from −39‰ to −158‰ (mean value of −107‰) for dicotyledonous species and from −80‰ to −200‰ (mean value of −140‰) for monocotyledonous species. The mean εwax-p value for gymnosperms is −106‰.

Discussion

Plant taxonomy and the alternative hypothesis

Liu et al.15 proposed that leaf wax δDn-alkane values were correlated with plant life forms (i.e., trees, shrubs and grasses). Subsequently, Liu and Yang16 compiled and analyzed leaf wax δDn-alkane values from modern plants across the Northern Hemisphere and observed distinguishable distribution patterns of δDn-alkane between woody plants and herbaceous plants (grasses, herbs, forbs, etc.), with the herbaceous plants D-depleted by ca. 40‰. Surprisingly, based on their database we observed that the captured range of leaf wax δDn-alkane values in the herbaceous plants was obviously larger than that in woody plants, with some herbaceous plants (forbs and herbs) obviously possessing higher δDn-alkane values of leaf wax, reaching δD values similar to those of woody plants despite the fact that they grew under the same environmental condition in the same region and utilized the same hydrogen source (Supplementary Table S2). When we regrouped these plants according to their major taxonomic lineages (e.g., eudicots, monocots and gymnosperms), we discovered that the plant taxonomy underpins such correlations at a global scale. Therefore, plant taxonomic lineages have a significant effect on leaf wax δDn-alkane values.

In order to further explore the difference in leaf wax δDn-alkane values between dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous species, we analyzed leaf water δD values and corresponding leaf wax δDn-alkane values both at the whole-leaf scale and at the segmented-leaf scale from representatives of these two major plant groups (Fig. 2a,b). At the whole leaf scale, no significant difference in leaf water δD values was observed between dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous species, while the corresponding leaf wax δDn-alkane values differed up to 43‰ (Binxian, Supplementary Table S4) and 32‰ (Xi’an and Lantian, Supplementary Table S5) (Fig. 2a), similar to the result obtained by Liu et al15. Therefore, the data indicate that the difference in leaf wax δDn-alkane values between dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous species dose not result from the D-enriched leaf water by evapotranspiration or other environmental factors (temperature, relative humidity, light, etc.). Grieu et al.37 observed that soil water δD values increased with depths whereas Kahmen et al.28 found the opposite results, suggesting that the difference of soil water utilized by plants may not be the main cause for the observed difference in leaf wax δDn-alkane values among different plant species.

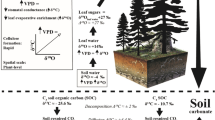

Variations in leaf water and corresponding leaf wax δDn-alkane values.

Variations of leaf water and corresponding leaf wax δDn-alkane values on whole leaves from Xi’an, Lantian and Binxian (a). Treatment on segmented leaf sections conducted from base to tip in monocotyledonous leaves and in base-to-tip and center-to-margin directions in dicotyledonous leaves, resulting difference in εwax-lw between dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous species. The difference in εwax-lw values derived from the quality-weighted mean εwax-lw values from segmented leaves was responsible for the difference in leaf wax δDn-alkane values of whole leaf (b). Conceptual diagram illustrating a model of hydrogen isotope transformation in terrestrial plants. The transformation comprises two processes: D-enrichment by evapotranspiration and D-depletion by biosynthetic processes10. The veinal structures inside the leaves (veinal water pathways, green box) control the isotopic gradients of leaf water and corresponding leaf wax (c).

Hydrogen transformation processes from soil water to leaf wax for modern plants were presented in Fig. 2c. It is commonly accepted that little isotopic fractionation during the uptake of soil water via plant roots occurs38. Transpiration drives leaf water toward D-enrichment relative to soil water39, resulting leaf water to be utilized for biosynthesis of leaf wax n-alkanes with a discrimination of D during the biosynthetic fractionation (Fig. 2c)40. Deuterium enrichment in leaf water is a cornerstone to determine leaf wax δDn-alkane values because isotope tracer experiments have shown that leaf wax δDn-alkane values are directly inherited from that in leaf water pools41. Moreover, many studies have demonstrated that leaf water exhibited spatial isotopic gradients inside leaf blades29,30,31,32. Therefore, the underlying explanation for the interspecies δDn-alkane variation may be correlated with veinal water pathways or biosynthetic processes (biological factors) (Fig. 2c).

At the segmented-leaf scale, leaf wax δDn-alkane values in Hierochloe glabra (a monocot) showed an increasing trend from base to the tip along the blade by 30‰ (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Table S3), similar to a previous result obtained from three tall grasses (Miscanthus sinensis, a monocot)35. In contrast, dicotyledonous blades of Rheum palmatum L. showed a progressively increase in leaf wax δDn-alkane values from base to tip and from center to margins (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Table S3). Compared with spatial variations in leaf wax δDn-alkane values, leaf water D-enrichment patterns inside leaf blades are similar to leaf wax spatial variations between dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous species (Fig. 2b). There was a progressive enrichment of leaf water δD values in the base-to-tip direction in monocotyledonous species and base-to-tip and center-to-margin directions in dicotyledonous species (Fig. 2b). Previous studies have established that the isotope enrichment in 18O from the base to tip along the blades in monocotyledonous species29,30. Likewise, the progressively increasing enrichments in 18O or D in both longitudinal (along the leaf midrib) and transversal (perpendicular to the midrib) directions were also observed in dicotyledonous species31,33. Therefore, the consistent variations in leaf wax δDn-alkane values and corresponding leaf water δD values indicate that veinal water pathways are unlikely to be the main cause for the observed difference in leaf wax δDn-alkane values between dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous species.

Moreover, leaf wax δDn-alkane value of whole leaves Hierochloe glabra (a monocot) was −201‰ and that of the whole leaf in Rheum palmatum L. (a dicot) was −184‰ (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Table S3), with 17‰ difference in leaf wax δDn-alkane values, consistent with observed patterns between the two major taxonomic groups with our above analysis of monocotyledonous species being D-depleted. The quality-weighted mean εwax-lw values inside the leaf blades between leaf water and corresponding leaf wax in dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous species were showed in Table S3. The biosynthetic fractionation between leaf water and leaf wax (εwax-lw) in monocotyledonous blades were from −205‰ to −208‰ with a quality-weighted average of −206‰, while the εwax-lw value from base to the tip along the margin of a dicotyledonous leaf was quality-weighted average of −189‰ and that along the center was quality-weighted average of −187‰, with an overall quality-weighted average of −188‰ in dicotyledonous blade (Supplementary Table S3). The difference in average biosynthetic fractionation εwax-lw values between dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous species was 18‰, consistent with the difference in leaf wax δDn-alkane values of whole leaves (Fig. 2b). Therefore, we believe that the different εwax-lw values between dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous species is the primary cause for the difference in leaf wax δDn-alkane values between the two major angiosperm divisions.

The different biosynthetic fractionation factors (εwax-lw) between the major plant lineages (eudicots versus monocots) may derive from different hydrogen sources during lipid synthesis. Three potential sources of isotopic variability in lipid hydrogen have been identified: (1) isotope effects of water (including exchange of organic H with H2O) associated with biosynthetic reactions, (2) the isotopic composition of biosynthetic precursors (acetate and acetyl-CoA) and (3) the isotopic composition of added agents such as NADPH during biosynthesis24. About 25% of the total hydrogen in n-alkanes is obtained directly from water, 25% of that from biosynthetic precursors and one-half supplied by NADPH42. A detailed analysis on the mean δD values of the hydrogen sources was ca. +30‰ for water, ca. −70‰ for carbohydrate and ca. −250‰ for NADPH43. Biosynthetic fractionation εwax-lw integrates a suite of biochemical fractionations during the biosynthesis of leaf wax n-alkanes; in particular, NADPH-derived hydrogen additions seem to be an important process because NADPH-derived hydrogen is strongly depleted relative to biosynthetic water. However, the isotope compositions of water and biosynthetic precursors should be the same when various plants grow at the same site. Therefore, NADPH-derived hydrogen additions may determine biosynthetic fractionation factor, εwax-lw27, which lead to different leaf wax δDn-alkane distribution patterns between dicotyledonous/gymnosperms and monocotyledonous species. Sternberg et al.44,45 concluded that biological factors appeared to be as important as environmental factors in determining hydrogen isotope ratios of plant cellulose among plants with different photosynthetic pathways (C3, C4 and CAM).

Furthermore, the different biosynthetic fractionations (εwax-lw) between dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous species may also be due to their different leaf morphologies and different growth strategies27,28,46. In dicotyledonous species, leaf waxes form during the brief period of leaf expansion, with the majority of leaf-wax formation subsiding after leaf expansion47. Monocotyledonous leaves, in contrast, grow from a basal intercalary meristem and wax development throughout the day and lifetime of the leaf47. Our data at the segmented-leaf scale have shown that spatial variations in leaf water and leaf wax δD values, with monocotyledonous leaf having base-to-tip D-enrichment, whereas dicotyledonous leaf having base-to-tip and center-to-margin D-enrichment. Monocotyledonous leaf develops using a D-depleted source pool from a basal intercalary meristem at the base of the leaf. Nevertheless, in dicots the evaporative D-enrichment of leaf water in developing leaves can be in the same range as in fully matured leves46. So the two separate mechanisms for growth strategies may also produce the different biosynthetic fractionations (εwax-lw) between dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous species.

Additionally, the leaf wax δDn-alkane distribution pattern in gymnosperms is similar to that in dicotyledonous species (Supplementary Fig. S3). Moreover, the εwax-p values between leaf wax δDn-alkane values and precipitation δD values in gymnosperm are also similar to those of dicotyledonous species. The fact that dicotyledonous species and gymnosperms have different leaf architectures and different vein structures (veinal water pathways) but have similar εwax-p values would also support the notion that evaporation due to different leaf physiognomy is unlikely the cause for the differences in leaf wax δDn-alkane values. Therefore, we hypothesized that the biosynthetic hydrogen isotope fractionation during lipid synthesis in gymnosperm is similar to dicotyledonous species.

Global plant taxonomic lineages (eudicots versus monocots)

Liu and Yang16 analyzed leaf wax δDn-alkane values from modern plants across the Northern Hemisphere and observed different distribution patterns between woody plants and herbaceous plants, with herbaceous plants being D-depleted by ca. 40‰ (Fig. 3a). Applying our expanded database, we regrouped plant taxa based upon major angiosperm divisions (eudicots and monocots) and observed distinguishable distribution patterns in leaf wax δDn-alkane values between the two groups, with monocotyledonous species having lower δDn-alkane values (Fig. 3b). We found that most of the herbaceous plants (mainly forbs and herbs) with higher δDn-alkane values in Liu and Yang16 database in fact belong to eudicot species. When we regroup these previous outliers based on plant taxonomy rather than plant life forms, the division of leaf wax δDn-alkane values between the two major plant groups become more distinguished (Fig. 3a,b; Supplementary Fig. S4). In general, leaf wax δDn-alkane values of both dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous species decreased with the increase of latitudes, responding to the latitudinal effect of precipitation δD in the Northern Hemisphere. Interestingly, the rates of decreased variations in leaf wax δDn-alkane values of both monocotyledonous and dicotyledonous species followed approximate similar slopes (Fig. 3b). The parallel variation lines would suggest that region-specific environmental factors are not the cause for the observed difference in leaf wax δDn-alkane values between the two major taxonomic lineages, the inherent biosynthetic isotope fractionations of plant taxonomy may act as the force driving the differences.

Leaf wax δDn-alkane values in living angiosperms along a latitudinal gradient in the North Hemisphere.

Comparisons of leaf wax δDn-alkane values (n = 233) between herbaceous plants and woody plants and the precipitation average δD were presented as δD = −0.037 × (latitude)2 + 1.1674 × (latitude) −35.423 from Liu and Yang (2008) (a). Comparisons between monocotyledonous and dicotyledonous species based on our expanded database (n = 503). Notice, the observed higher δDn-alkane values in Stiffkey saltmarsh (Eley et al., 2014) may be due to the fact that samples were obtained from a salt marsh (b). The parallel εwax-p values in dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous species are insensitive to variations of precipitation δD values, suggesting different biosynthetic processes between eudicots and monocots (c).

Recently, Kahmen et al.27 observed that the full extent of leaf water evaporative D-enrichment was recorded in leaf wax δDn-alkane values for dicotyledonous species, whereas only 18–68‰ of the D-enrichment in leaf water was recorded in leaf wax δDn-alkane values for monocotyledonous species. While Kahmen et al.27 attributed the difference in evaporative D-enrichment of leaf water as being recorded in leaf wax δDn-alkane values, the different biological behaviors between dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous species can also be explained by the underlying different biosynthetic processes. Therefore, our data suggest that the difference in leaf wax δDn-alkane values between eudicot and monocot species is primarily driven by different εwax-lw values correlated with biological factors of the two major plant groups.

Implications for the reconstruction of global precipitation

Previous studies have demonstrated a strong correlation between leaf wax δDn-alkane values in modern plants (or sediments) and precipitation δD values both at regional and global scales13,15,16,17. Precipitation δD value is a dominating factor that exercises the first order of control for plant leaf wax δDn-alkane values along the latitudes16. Our new data confirm that the εwax-p values between leaf wax δDn-alkane values of major plant lineages (eudicots versus monocots) and precipitation δD values exhibited distinguishable distribution patterns at a global scale, with monocotyledonous species having larger εwax-p values than dicotyledonous species (Fig. 3c). The εwax-p values vary ranging from −39‰ to −158‰ for dicotyledonous species and from −80‰ to −200‰ for monocotyledonous species. The mean εwax-p value is −107‰ for dicotyledonous species (−106‰ for gymnosperms) and −140‰ for monocotyledonous species, similar to the results of −113‰ for C3 eudicots and −149‰ for C3 monocots13. However, the parallel εwax-p patterns along with the latitudes suggest that different biosynthetic processes between dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous species are insensitive to regional variations of precipitation δD values (Fig. 3c), further supporting the notion that the underlying difference in leaf wax δDn-alkane values between dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous species is due to different hydrogen fractionations during biosynthetic processes.

As different mean εwax-p values (−107‰ for eudicots/ gymnosperms; −140‰ for monocots) corresponds to different biosynthetic processes with different biosynthetic fractionation εwax-lw values in different major plant lineages, plant taxonomy does play an important role in controlling leaf wax δDn-alkane values in higher plants. Our data imply that (1) we must distinguish vegetation change signals form environmental variation signals during the reconstruction of paleoenvironment, (2) the previous practice of using a taxonomic blind average εwax-p value to reconstruct paleo-precipitation δD values without considering the composition of vegetation may lead to large errors.

Conclusions

Our reanalysis of an expanded database of available leaf wax δDn-alkane records from modern higher plants revealed that the differences in leaf wax δDn-alkane values among different plant life forms (e.g., grasses, shrubs, trees, herbs, forbs, veins, ferns and aquatic plants etc.) are in fact underpinned by the plant taxonomic division of major systematic lineages, with monocotyledonous species being D-depleted relative to dicotyledonous species. This alternative interpretation explains the previous observed D-enrichment δDn-alkane values of leaf wax from some outlier eudicot herbaceous samples in a given site and improved global correlations between leaf wax δDn-alkane values and precipitation δD. Our data further suggest that biological factors, such as different hydrogen additions (NADPH-derived) for lipid synthesis, play key roles in determining different hydrogen isotope fractionations under different plant lineages. Additionally, the different growth strategies between dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous leaves may also produce different biosynthetic fractionation factors (εwax-lw). Future studies may focus on detailed biochemical process and molecular mechanism that lead to distinguished hydrogen biosynthetic fractionations among major taxonomic lineages in higher plants. The recognition of various εwax-p values between different plant taxonomic lineages imply that using average εwax-p values without the knowledge of vegetation may lead to large errors for the reconstruction of ancient precipitation δD values. Our findings further confirm that it is imperative to take this “plant taxonomy effect” into account when employing δDn-alkane values of leaf wax as a paleo-hydrology proxy in areas where vegetation change has been pronounced.

Materials and Methods

Modern higher plants were sampled in Northwestern China and a larger dataset of available δDn-alkane data that was previously published from various regions in the Northern Hemisphere were compiled (Fig. 4; Supplementary Table S1). For the whole leaf studies, we sampled 68 plants from Heshui County in May and September of 2013 and some published δDn-alkane data from Xi’an and Lantian were used in this analysis36. To ensure a complete representation of the whole leaf signal, we collected intact leaves on the account of likely leaf water isotopic gradients along the leaf blade29.

Geographic map showing sample sites in Heshui, Lantian and Xi’an and the distribution of compiled modern leaf wax δDn-alkane values of higher plants across the North hemisphere.

Black rectangles are data based upon Liu and Yang, (2008); red dots are additional data points. (Fig. 4 was created by CorelDRAW 12; My co-authors and I grant NPG to publish the image under an Open Acess license; We grant NPG to publish the image in all formats i.e. print and digital).

In order to investigate isotopic gradients inside leaf blades, we sampled Rhleum palmatum L. (an eudicot) and Hierochloe glabra (a monocot) at the same site from Binxian on 19 May, 2014. About 5–7 leaves with similar sizes were collected for each species for experimental analysis. Analyses were conducted for whole leaves as well as for leaf segments. Whole leaves of both species were treated to obtain leaf water δD values and leaf wax δDn-alkane values. The dicotyledonous blade of Rheum palmatum L. was cut into segments along the main veins and margins of a leaf and the leaves of species Hierochloe glabra were segmented from base to the tip in order to obtain variations of leaf water δD and leaf wax δDn-alkane values for various sections of the leaf blade (Supplementary Fig. S1). These plants grew on the Chinese Loess Plateau where they received full sun and natural rainfall without human disturbance. We collected these plant samples between 12 pm to 15 pm to capture the maximum diurnal enrichment in leaf water isotopic composition48. Leaf samples were immediately enclosed in 100-ml screw-cap plastic vials with Parafilm® and kept in a dry cooler (ca. 4 °C) in the field until transferred to the laboratory.

Leaf water was extracted using a cryogenic vacuum distillation49 and leaf water δD values were determined using a L2130-I isotope water analyzer (Picarro, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) with the Micro-Combustion ModuleTM (MCM) to remove organic compounds contaminating water samples50,51. The measurement precision for water δD analysis was 1%. After the extraction of leaf water, the leaf remains were used for leaf wax n-alkane extraction and hydrogen isotope measurement as described in Liu et al.15. The H3+ factor was determined daily and remained at 2.325 ± 0.008 (n = 6) during sample analysis, ensuring stable ion source conditions. A mixed laboratory standard consisting of six n-alkanes (C21, C25, C27, C29, C31 and C33) was analyzed between every four measurements to evaluate the reproducibility and accuracy of the instrument. The standard deviation for the n-alkane working standard was 3‰ and each sample was analyzed in duplicate or more, with the standard deviation usually less than 3‰. The accuracy from co-injected primary standards (n-alkanes available from A. Schimmelmann, Biogeochemical Laboratories, Indiana University) was ± 3‰ (n = 6). The δD values are reported relative to the Vienna mean standard ocean water (VSMOW).

In order to test the hypothesis at the global scale, we compiled the available modern leaf wax δDn-alkane data from various locations in the Northern Hemisphere to form an expanded database (n = 503) for statistical analysis. The database included published δDn-alkane data from China15,16, Japan and Thailand20, North America14,18,39,47,52 and European regions53,54,55,56 and some regions in the high latitudes of the Arctic19, spanning from 16°06′N to 79°5′N in latitude and from 0°55′E to 142°11′E and from 148°56′W to 71°58′W in longitude, including various plant life forms (Fig. 4; Supplementary Table S2).

Pearson correlations were conducted to investigate various correlations between δDn-alkane values of plant taxonomies and various geographic and environmental factors. One-way ANOVA tests were used to identify differences among factors at P = 0.001. Student’s t-tests were used to identify differences between two factors. The hydrogen isotopic fractionation factor (εwax-lw) between leaf wax n-alkane (δDwax) and corresponding leaf water (δDlw) is calculated as:

To quantify the influence of precipitation δD values on leaf wax δDn-alkane values, the apparent hydrogen fractionation factor (εwax-p) between leaf wax and precipitation is determined as the following:

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Liu, J. et al. Different hydrogen isotope fractionations during lipid formation in higher plants: Implications for paleohydrology reconstruction at a global scale. Sci. Rep. 6, 19711; doi: 10.1038/srep19711 (2016).

References

Eglinton, G. & Hamilton, R. J. Leaf epicuticular waxes. Science 156, 1322–1335 (1967).

Bush, R. T. & McInerney, F. A. Leaf wax n-alkane distributions in and across modern plants: Implications for paleoecology and chemotaxonomy. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 117, 161–179 (2013).

Yang, H. & Huang, Y. S. Preservation of lipid hydrogen isotope ratios in Miocene lacustrine sediments and plant fossils at Clarkia, northern Idaho, USA. Org. Geochem. 34, 413–423 (2003).

Smith, F. A., Wing, S. L. & Freeman, K. H. Magnitude of carbon isotope excursion at the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum: the role of plant community change. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 262, 50–65 (2007).

Hou, J. Z., William, J. D. & Huang, Y. S. Can sedimentary leaf waxes record D/H ratio of continental precipitation ? Field, model and experimental assessments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 72, 3503–3517 (2008).

Cranwell, P. A. Chain-length distribution of n-alkanes from lake sediments in relation to post-glacial environmental change. Freshwater Biol. 3, 259–265 (1973).

Sternberg L. S. L. D/H ratios of environmental water recorded by D/H ratios of plant lipids. Nature 333, 59–61 (1988).

Meyers, P. A. Applications of organic geochemistry to paleolimnological reconstructions: a summary of examples from the Laurentian Great Lakes. Org. Geochem. 34, 261–289 (2003).

Liu, W. G. & Huang, Y. S. Compound specific D/H ratios and molecular distributions of higher plant leaf waxes as novel paleoenvironmental indicators in the Chinese Loess Plateau. Org. Geochem. 36, 851–860 (2005).

Sachse, D. et al. Molecular paleohydrology: Interpreting the hydrogen-isotope biomarkers from photosynthesizing organisms. Ann. Rev. Earth Planetary Sci. 40, 221–249 (2012).

Wang, Z. et al. 1700 -year n-alkanes hydrogen isotope record of moisture changes in sediments from Lake Sugan in the Qaidam Basin northeastern Tibetan Plateau. Holocene 23, 1350–1354 (2013).

Huang, Y. S., Shuman, B., Wang, Y. & Webb, T. I. Hydrogen isotope ratios of palmitic acid in lacustrine sediments record late Quaternary climate variations. Geology 30, 1103–1106 (2002).

Sachse, D., Radke, J. & Gleixner, G. Hydrogen isotope ratios of recent lacustrine sedimentary n-alkanes record modern climate variability. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 68, 4877–4889 (2004).

Smith, F. A. & Freeman, K. H. Influence of physiology and climate on δD of leaf wax n-alkanes from C3 and C4 grasses. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 70, 1172–1187 (2006).

Liu, W. G. & Yang, H. & Li, L. Hydrogen isotopic compositions of n-alkanes from terrestrial plants correlate with their ecological life forms. Oecologia 150, 330–338 (2006).

Liu, W. G. & Yang, H. Multiple controls for the variability of hydrogen isotopic compositions in higher plant n-alkane from modern ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 14, 2166–2177 (2008).

Collins, J. A. et al. Estimating the hydrogen isotopic composition of past precipitation using leaf-waxes from western Africa. Quat. Sci. Rev. 65, 88–101 (2013).

Hou, J. Z., Andrea, W. J. D., MacDonald, D. & Huang, Y. S. Hydrogen isotopic variability in leaf waxes among terrestrial and aquatic plants around Blood Pond, Massachusetts (USA). Org. Geochem. 38, 977–984 (2007).

Yang, H., Liu, W. G., Leng, Q., Hren, M. T. & Pagani, M. Varation in n-alkane δD values from terrestrial plants at high latitude: Implications for paleoclimate reconstruction. Org. Geochem. 42, 283–288 (2011).

Chikaraishi, Y. & Naraoka, H. Compound-specific δD-δ13C analysis of n-alkane extracted from terrestrial and aquatic plants. Phytochemistry 63, 361–371 (2003).

Polissar, P. J. & Freeman, K. H. Effects of aridity and vegetation on plant-wax δD in modern lake sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 5785–5797 (2010).

Terwilliger, V. J. & DeNiro, M. J. Hydrogen isotope fractionation in wood-producing avocado seedlings: biological constraints to paleoclimatic interpretations of δD values in tree ring cellulose nitrate. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 59, 5199–5207 (1995).

Yakir, D. & DeNiro, M. J. Oxygen and hydrogen isotope fractionation during cellulose metabolism in Lemna gibba L. Plant Physiol. 93, 325–332 (1990).

Sessions, A. L., Burgoyne, T. W., Schimmelmann, A. & Hayes, J. M. Fractionation of hydrogen isotope in lipid biosynthesis. Org. Geochem. 30, 1193–1200 (1999).

Chikaraishi, Y., Naraoka, H. & Poulson, S. R. Hydrogen and carbon isotope fractionations of lipid biosynthesis among terrestrial (C3, C4 and CAM) and aquatic plants. Phytochemistry 65, 1369–1381 (2004).

Zhou, Y. P. et al. Temperature effect on leaf water deuterium enrichment and isotopic fractionation during leaf lipid biosynthesis: result from controlled growth of C3 and C4 land plants. Phytochemistry 72, 207–213 (2011).

Kahmen, A., Schefuss, E. & Sachse, D. Leaf water deuterium enrichment shapes leaf wax n-alkane δD values of angiosperm plants I: Experimental evidence and mechanistic insights. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 111, 39–49 (2013a).

Kahmen, A. et al. Leaf water deuterium enrichment shapes leaf wax n-alkane δD values of angiosperm plants II: Observational evidence and global implications. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 111, 50–63 (2013b).

Helliker, B. R. & Ehleringer, J. R. Establishing a grassland signature in veins: 18O in the leaf water of C3 and C4 grasses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97, 7894–7898 (2000).

Helliker, B. R. & Ehleringer, J. R. Differential 18O enrichment of leaf cellulose in C3 versus C4 grasses. Funct. Plant Biol. 29, 435–442 (2002).

Gan, K. S., Wong, S. C., Yong, J. W. H. & Farquhar, G. D. 18O spatial patterns of vein xylem water, leaf water and dry matter in cotton leaves. Plant Physiol. 130, 1008–1021 (2002).

Gan, K. S., Wong, S. C., Yong, J. W. H. & Farquhar, G. D. Evaluation of models of leaf water 18O enrichments of spatial patterns of vein xylem, leaf water and dry matter in maize leaves. Plant Cell Environ. 26, 1479–1495 (2003).

Shu, Y. et al. Isotopic studies of leaf water. Part 1: A physically based two-dimensional model for pine needles. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 72, 5175–5188 (2008).

Song, X., Barbour, M. M., Farquhar, G. D., Vann, D. R. & Helliker, B. R. Transpiration rate relates to within- and across-species variations in effective path length in a leaf water model of oxygen isotope enrichment. Plant Cell Environ. 36, 1338–1351 (2013).

Gao, L. & Huang, Y. S. Inverse gradients in leaf wax δD and δ13C values along grass blades of Miscanthus sinensis: Implications for leaf wax reproduction and plant physiology. Oecologia 172, 347–357 (2013).

Liu, J. Z., Liu, W. G. & An, Z. S. Insight into the reasons of leaf wax δDn-alkane values between grasses and woods. Sci. Bull. 60, 549–555 (2015).

Grieu, P., Lucero, D. W., Ardiani, R. & Ehleringer, J. R. The mean depth of soil water uptake by two temperate grassland species over time subjected to mild soil water deficit and competitive association. Plant Soil 230, 197–209 (2001).

Ehleringer, J. R., Phillips, S. L., Schuster, W. S. F. & Sandquist, D. R. Differential utilization of summer rains by desert plants. Oecologia 88, 430–434 (1991).

Feakins, S. J. & Sessions, A. L. Control on the D/H ratios of plant leaf waxes in an arid ecosystem. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 2128–2141 (2010).

Sessions, A. L. Seasonal changes in D/H fractionation accompanying lipid biosynthesis in Spartina alterniflora. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 70, 2153–2162 (2006).

Kahmen, A., Dawson, T. E., Vieth, A. & Sachse, D. Leaf wax n-alkane δD values are determined early in the ontogeny of Populus trichocarpa leaves when grown under controlled environmental conditions. Plant Cell Environ. 34, 1639–1651 (2011).

Sessions, A. L., Jahnke, L. L., Schimmelmann, A. & Hayes, J. M. Hydrogen isotope fractionation in lipids of the methane-oxideizing bacterium Methylococcus capsulatus. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 66, 3955–3969 (2002).

Schmidt, H.-L., Werner, R. A. & Eisenreich, W. W. Systematics of 2H patterns in natural compounds and its importance for the elucidation of biosynthetic pathways. Phytochemi. Rev. 2, 61–85 (2003).

Sternberg, L. & DeNiro, M. J. Isotopic composition of cellulose from C3, C4 and CAM plants growing near one another. Science 220, 947–949 (1983).

Sternberg, L., DeNiro, M. J. & Ting, I. P. Carbon, hydrogen and oxygen isotope ratios of cellulose from plants having intermediary photosynthetic modes. Plant Physiol. 74, 104–107 (1984).

McInerney, F. A., Helliker, B. R. & Freeman K. H. Hydrogen isotope ratios of leaf wax n-alkanes in grasses are insensitive to transpiration. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 75, 541–554 (2011).

Tipple, B. J., Berke, M. A., Doman, C. E., Khachaturyan, S. & Ehleringer, J. R. Leaf-wax n-alkanes record the plant-water environment at leaf flush. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, 2659–2664 (2013a).

Romero, I. C. & Feakins, S. I. Spatial gradients in plant leaf wax D/H across a coastal salt marsh in southern California. Org. Geochem. 42, 618–629 (2011).

West, A. G., Patrickson, S. J. & Ehleringer, J. R. Water extraction times for plant and soil materials used in stable isotope analysis. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 20, 1317–1321 (2006).

Picarro. Micro-Combustion ModuleTM (MCM): elimination of organics datasheet. (2012) http://www.picarro.com/site/default/files/Micro-Combustion%20Module20Datasheet.pdf [accessed: 13th February 2015].

Martín-Gómez, P., Barbeta, A., Voltas, J., Peñuelas, J., Dennis, K., Palacio, S., Dawson, T. E. & Ferrio J. P. Isotope-ratio infrared spectroscopy: a reliable tool for the investigation of plant-water sources? New Phytol. doi: 10. 1111/nph.13376 (2015).

Tipple, B. & Pagania, M. Environmental control on eastern broadleaf forest species’ leaf wax distribution and D/H ratios. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 111, 64–77 (2013b).

Sachse, D., Radke, J. & Gleixner, G. δD values of individual n-alkanes from terrestrial plants along a climatic gradient – Implications for the sedimentary biomarker record. Org. Geochem. 37, 469–483 (2006).

Sachse, D., Kahmen, A. & Glexiner, G. Significant seasonal variation in the hydrogen isotopic composiion of leaf-wax lipids for two deciduous tree ecosystems (Fagus sylvativa and Acer pseudoplatanus). Org. Geochem. 40, 732–742 (2009).

Sachse, D., Gleixner, G., Wilkes, H. & Kahmen, A. Leaf wax n-alkane δD values of field-grown barley reflect leaf water δD values at the time of leaf formation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 6741–6750 (2010).

Eley, Y., Dawson, L., Black, S., Andrews, J. & Pedentchouk, N. Understanding 2H/1H systematics of leaf wax n-alkanes in coastal plants at Stiffkey saltmarsh, Norfolk, UK. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 128, 13–28 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Drs. Hao Wan and Huanye Wang, who helped with field sampling and Yunning Cao, Meng Xing and Zheng Wang who provided laboratory assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.J.Z. conceived and conducted the experiments, performed research, analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. L.W.G. conceived and designed the experiments, analyzed and discussed the results. H.Y. discussed the results, analyzed the data and provided assistance in manuscript writing. A.Z.S. conceived the project and discussed results.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Liu, W., An, Z. et al. Different hydrogen isotope fractionations during lipid formation in higher plants: Implications for paleohydrology reconstruction at a global scale. Sci Rep 6, 19711 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep19711

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep19711

This article is cited by

-

Insights into the provenance implication of leaf wax n-alkanes along the lower Yellow River

Science China Earth Sciences (2024)

-

Seasonal variations of leaf wax n-alkane distributions and δ2H values in peat-forming vascular plants from the Dajiuhu peatland, central China

Frontiers of Earth Science (2022)

-

Global-scale altitude effect on leaf wax n-alkane δD values in terrestrial higher plants

Science China Earth Sciences (2021)

-

Comparison of different chain n-fatty acids in modern plants on the Loess Plateau of China

Frontiers of Earth Science (2020)

-

Altitudinal effect of soil n-alkane δD values on the eastern Tibetan Plateau and their increasing isotopic fractionation with altitude

Science China Earth Sciences (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.