Abstract

Lactobacillus reuteri is a dominant member of intestinal microbiota of vertebrates and occurs in food fermentations. The stable presence of L. reuteri in sourdough provides the opportunity to study the adaptation of vertebrate symbionts to an extra-intestinal habitat. This study evaluated this adaptation by comparative genomics of 16 strains of L. reuteri. A core genome phylogenetic tree grouped L. reuteri into 5 clusters corresponding to the host-adapted lineages. The topology of a gene content tree, which includes accessory genes, differed from the core genome phylogenetic tree, suggesting that the differentiation of L. reuteri is shaped by gene loss or acquisition. About 10% of the core genome (124 core genes) were under positive selection. In lineage III sourdough isolates, 177 genes were under positive selection, mainly related to energy conversion and carbohydrate metabolism. The analysis of the competitiveness of L. reuteri in sourdough revealed that the competitivess of sourdough isolates was equal or higher when compared to rodent isolates. This study provides new insights into the adaptation of L. reuteri to food and intestinal habitats, suggesting that these two habitats exert different selective pressure related to growth rate and energy (carbohydrate) metabolism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lactobacillus reuteri persist in intestinal microbiota of vertebrate animals as well as in food fermentations1,2,3,4. L. reuteri colonizes humans and animal hosts2,4; the phylogenetic differentiation of strains of L. reuteri originating from different hosts reflects co-evolution of L. reuteri with its vertebrate hosts4. This evolutionary adaptation differentiates the species L. reuteri in host-adapted phylogenetic lineages comprised of isolates from rodents (lineages I and III), humans (lineages II and VI), pigs (lineages IV and V) and poultry (lineage VI)4,5.

L. reuteri also occur in industrial sourdoughs6 and cereal fermentations in tropical climates1,7. Sourdoughs are typically maintained by continuous propagation, a process which rapidly selects for the most competitive microbiota. Major selection criteria for fermentation microbiota in cereal ecosystems are rapid growth in cereal substrates and acid resistance1,8,9,10. Food isolates of L. reuteri match to host-adapted lineages11 and maintain host-specific physiological traits12,13,14, including the ability to colonize the lineage-specific hosts11,15.

The differentiation of L. reuteri into host-adapted lineages implies that an extra-intestinal habitat did not exist for a majority of the evolution of this species14. However, the occurrence of L. reuteri in the human-made habitat sourdough provides the opportunity to study the “reverse adaptation” of vertebrate symbionts to an extra-intestinal habitat. This study employed comparative genomics of L. reuteri to evaluate the genetic determinants of this adaptation or selection process. Genome sequences of intestinal strains of L. reuteri were retrieved from public databases and compared to four genome sequences of rodent-lineage sourdough isolates16. The sourdough isolates L. reuteri LTH2584, TMW1.112 and TMW1.656 originate from SER sourdough, a sourdough that is used industrially for production of a baking improver9. This sourdough has been maintained by continuous propagation since about 1970. L. reuteri LTH2584, TMW1.1112 and TMW1.656 were isolated from this sourdough in 1988, 1994 and 19986,9; all of these strains produce reutericyclin, a tetramic acid derivative with antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive bacteria6,16. L. reuteri LTH5448 was isolated from a different sourdough processed at the same facility in 20008,17; this strains does not produce reutericyclin but maintains the reutericyclin genomic island and reutericyclin resistance16,17. Comparative genomics analyses included analyses of the core genome as well as gene gain and gene loss events that were studied on the basis of the pan-genome. We also performed positive selection analysis for these core genes of the whole species. Finally, the competitiveness of sourdough isolates of L. reuteri in model sourdoughs was compared to the competitiveness of closely related intestinal isolates.

Results

Phylogenetic analysis of 16 sequenced L. reuteri strains including 4 sourdough strains

The phylogenetic analysis was carried out with all available genome sequences of L. reuteri, including 4 genome sequences of sourdough isolates16. A phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the core genome of L. reuteri (Fig. 1A). Strains of L. reuteri were grouped into 5 clusters corresponding to the host-adapted lineages I (rodent), II (human), III (rodent), IV (pig) and VI (poultry and human). Sourdough strains were assigned to the rodent-adapted lineages I and III, in agreement with previous analyses11. L. reuteri LTH5448 clustered with lineage I rodent isolates; L. reuteri LTH2584, TWM1.112 and TWM1.656 were grouped into lineage III together with the rodent isolates L. reuteri 100-23 and mlc3. L. reuteri LTH2584, an SER sourdough isolate obtained in 1988, was more closely related to L. reuteri TWM1.656, which was isolated from SER sourdough in 1998, than to L. reuteri TWM1.112, which was isolated from the same sourdough in 19946.

Phylogenetic analysis of the 16 L. reuteri strains.

(A) Phylogenetic tree based on core genes. Roman numerals designate the host adapted lineages of L. reuteri4,15. Strains isolated from sourdough are marked in red. Only bootstrap values above 90 were shown. Branch lengths are proportional to the number of substitutions per site (see scale bar). (B) Genome tree based on gene content matrix. Scale bar represent the genetic distance as determined by Jaccard distance.

A gene content tree was constructed to study the gain and loss of genes among these strains. Here, strains sharing more genes were clustered together (Fig. 1B). The topology of the gene content tree was different from the core genome phylogenetic tree, indicating gene loss or acquisition of genes by horizontal genetic transfer. Three clusters corresponding to linages II, IV and VI were maintained but the gene content tree highlighted differences between strains in each cluster. For example, the four lineage II L. reuteri MM4-1A, MM2-3, DSM 20016 and JCM 1112 were not separated in the core genome phylogenetic tree but differentiated in two groups by calculating the gene content tree (Fig. 1B). L. reuteri DSM20016 and JCM1112 were derived from the same original isolate, F275 and differences between these two strains may reflect loss of genes during propagation in the laboratory18. The two lineage III strains L. reuteri 100-23 and mlc3 showed a quite different gene content. Remarkably, all four sourdough isolates were grouped together despite their divergent phylogenetic origin. L. reuteri LTH5448 was more closely related to L. reuteri LTH2584 than to L. reuteri TWM1.112 and TWM1.656.

Comparative analysis of sourdough strains

To understand how the intestinal strains adapted to sourdough and to identify genes that are unique to sourdough isolates, the gene content similarity and dissimilarity of these strains was analysed. L. reuteri LTH2584, TWM1.112, TWM1.656 and 100-23 shared 1535 core genes (Fig. 2A); this core genome is higher than the core genome of the whole species5, reflecting that all these strains are grouped in lineage I. L. reuteri LTH2584 and 100-23 had more unique genes than L. reuteri TWM1.112 and TWM1.656 (Fig. 2A), which contributed to the distinct position of the former two strains in the gene content tree. Sourdough isolates shared 1523 core genes (Fig. 2B). Genes that were shared by all sourdough isolates but absent in other strains include the chromosomally encoded reutericyclin genomic island16, a putative aspartate racemase, a LytTr-domain protein with putative regulatory function and components of a putative ABC-transporter (Table 2). Genes that were only present in some of the sourdough isolates include a glycosyltransferases with putative function in protein glycosylation (LTH2584 and TMW1.656) and a putative hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenase (LTH2584 and TMW1.112) which catalyses the use of α-ketoglutarate as electron acceptor19. Of note, distributed genes that are present in sourdough isolates of L. reuteri and other strains include several putative enzymes of the shikimic acid pathway for biosynthesis of aromatic amino acids (Table 2). In summary, only genes coding for reutericyclin biosynthesis are unique to all sourdough isolates of L. reuteri.

Comparative analyses of genes shared between sourdough isolates of L. reuteri and L. reuteri 100-23 and among sourdough isolates.

(A) Venn diagram of core, distributed and unique gene numbers between the lineage III strains L. reuteri LTH2584, TMW1.656, TMW1.112 and 100-23. (B) Venn diagram of core, distributed and unique gene numbers among the Lineage III sourdough isolates L. reuteri LTH2584, TMW1.656, TMW1.112 and the Lineage I sourdough isolate L. reuteri LTH5448.

Positive selection of the core genes contributing to the adaptation of sourdough isolates

Analysis of positive selection aimed to identify the selective pressure on the core genome of L. reuteri and to determine whether sourdough and intestinal strains are subjected to a differential selective pressure. Initially, positive election was analysed in all 16 strains of L. reuteri. A total of 124 core genes were under positive selection (Fig. 3 and Table S2), representing 10.36% of the core genome. Among the genes that are under positive selection, 22% relate to metabolism, including transporters and enzymes for protein, amino acid, carbohydrate and lipid conversion. Several genes under positive selection were listed as “general functional prediction only”, but most of these predicted functions were also related to metabolic functions. Other abundant genes under positive selection relate to DNA replication, recombination and repair. When compared with the composition of the core genes, COG categories “translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis” and “general functional prediction only” were significantly enriched among genes under positive selection in all 16 core genomes of L. reuteri (P = 0.04, 0.03, one-sided binomial test). For the 20 genes in the former category, 8 are tRNA associated genes, 6 are ribosomal protein genes, 3 are 23S RNA-specific pseudouridylate synthases, 2 are translation elongation factor genes and 1 is methylase of polypeptide chain release factor gene (Table S2). For the latter category, most predicted functions relate to metabolism. For example, 6 out 21 were hydrolases and other were some reductases, permeases and esterases.

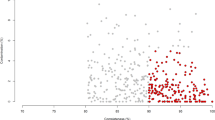

Proportions of positive selection of core genes in each COG category in all L. reuteri strains (gray bars) and the branch of sourdough isolates comprising L. reuteri LTH2584, TWM1.112 and TWM1.656 (white bars).

Site model M2a and its null model M1a were compared to infer genes under positive selection in the whole species. Branch-site mode and its null model were compared to study genes under positive selection across the COG categories. COG categories that were significantly enriched in all strains of the species L. reuteri, or in the Lineage III sourdough isolates are marked by an asterisk.

To identify the selective pressure acting on the sourdough isolates, the branch-site model and its null model were used to compare the function categories under positive selection in the branch comprising L. reuteri LTH2584, TWM1.112 and TWM1.656 to all other strains in the species. A total of 177 core genes were under positive selection in these lineage III sourdough isolates (Fig. 3 and Table S3). Of these, 135 genes were under positive selection only in this branch and the remaining 42 were under positive selection in the sourdough isolates as well as the remainder of the species. Of the core genes under positive selection in the sourdough branch, 33% related to metabolism (Fig. 3 and Table S3). Three COG categories were significant enriched in the lineage III sourdough isolates, “Energy production and conversion” (P = 5.9 * 10−6), “Carbohydrate transport and metabolism” (P = 0.03) and “Defense mechanisms” (P < 2.2 * 10−16) (Fig. 3). Examples of gene in these COG categories that are under positive selection include key metabolic enzymes such as maltose phosphorylase, lactate dehydrogenase, alcohol dehydrogenase and several sugar transport enzymes (Table S3).

Competitiveness of L. reuteri strains in sourdough: experimental design

To determine whether genomic adaptation of L. reuteri to the sourdough environment increases the competitiveness of strains, competition experiments sourdoughs were carried out. Competition experiments in back-slopped sourdoughs are a sensitive tool to determine the competitiveness of strains because even small differences in competitiveness result in predominance of the more competitive strain after few refreshments10,20. Experiments were performed with fermentation cycles of 1, 2, or 3 days. The selection of strains used in the competition experiments included the sourdough isolates L. reuteri LTH5448, LTH2584, TMW1.112 and TMW1.656; and the rodent isolates L. reuteri 100-23, mlc3 and lpuph. Two methods were used to to achieve strain specific quantification of L. reuteri in sourdough. When used in combination, qPCR and differential plate counts ensured that sourdough microbiota in all samples consisted of only of those strains used as inoculum and accurately quantified the strain specific contribution to the fermentation microbiota.

The competition experiments were evaluated by calculation of the relative fitness. An example for the evaluation of competition experiments by qPCR and differential viable cell counts is shown in Fig. 4; all experiments are shown in Figure S3 of the online supplementary material. The cell counts and the pH of sourdough were influenced by the fermentation time and the fermentation microbiota. Three day fermentation cycles results in lower cell counts and higher pH values at the end of the fermentation when the glutamate-decarboxylase positive L. reuteri LTH5448 was part of the fermentation microbiota (Figure S4,S5).

Composition of fermentation microbiota in binary strain competitions of strains of L. reuteri.

Sourdoughs were inoculated with L. reuteri LTH2584 and 100-23 (Panels A and B) or with L. reuteri LTH2584 and LTH5448 (Panels C and D) and maintained by continuous back-slopping with 10% inoculum over 10 fermentation cycles with 1 d incubation times. Sourdough microbiota were analysed by differential plate counts (Panels A and C) and results were expressed as log proportion of the individual strains to the total viable cell counts. Sourdoughs were also analysed by qPCR targeting strain-specific sequences and log DNA copy numbers converted to cell counts using the strain-specific calibration curves (Panels B and D). Results were expressed as proportion of the individual strains to the total cell counts. Symbols represent L. reuteri strains LTH2584 (◼), LTH5448 (□) and 100-23 (◯).

Competitiveness of L. reuteri strains in sourdough

The competitiveness of the sourdough isolates L. reuteri LTH2584 and LTH5448 was substantially higher when compared to the rodent isolate L. reuteri 100-23 (Fig. 5). This difference in competitiveness to the reutericyclin-sensitive L. reuteri 100-23 was equivalent for the reutericyclin-producing L. reuteri LTH2584 and the reutericyclin-negative L. reuteri LTH5448. To determine whether this increased competitiveness was influenced by reutericyclin-production, a competition experiment was carried out between the reutericyclin-producing L. reuteri TMW1.656 and the isogenic reutericyclin-negative and -sensitive L. reuteri TMW1.656ΔrtcNΔrtcT16. L. reuteri TMW1.656 and TMW1.656ΔrtcNΔrtcT exhibited a comparable competitiveness and were maintained in approximately equal cell counts over 6 fermentation cycles (Fig. 6). This result demonstrates that reutericyclin production does not substantially influence the competitiveness of L. reuteri strains in sourdough.

Relative fitness of strains of L. reuteri in sourdoughs backslopped with 1d, 2d, or 3d fermentation cycles.

The relative fitness of strains was calculated from differential cell counts (Panel A) and from qPCR with strain specific primers (Panel B) by using the equation  , where x, y denote the strains used in binary strain combinations, xF and yF denote the cell counts or gene copy numbers at the end of each fermentation cycle and x0 and y0 denote the cell counts or gene copy numbers at the beginning of each fermentation cycle. The relative fitness was calculated for the following strain combinations: L. reuteri LTH2584 versus 100-23 (white bars); L. reuteri LTH5448 versus 100-23 (grey bars); L. reuteri LTH2584 versus LTH5448 (white hatched); and lineage I strains consisting of L. reuteri LTH2584, TMW1.112 and TMW1.656 versus lineage III strain L. reuteri LTH5448 (grey hatched). Differential enumeration was not possible for the strain combination L. reuteri LTH5448 and 100-23, therefore, only qPCR data is shown for this strain combination. Each competition was performed in doughs with 10 fermentation cycles that were back-slopped every 1, 2 and 3 days per fermentation cycle, respectively. The data was expressed as mean ± standard deviation from experiments performed in duplicate with two technical replicates.

, where x, y denote the strains used in binary strain combinations, xF and yF denote the cell counts or gene copy numbers at the end of each fermentation cycle and x0 and y0 denote the cell counts or gene copy numbers at the beginning of each fermentation cycle. The relative fitness was calculated for the following strain combinations: L. reuteri LTH2584 versus 100-23 (white bars); L. reuteri LTH5448 versus 100-23 (grey bars); L. reuteri LTH2584 versus LTH5448 (white hatched); and lineage I strains consisting of L. reuteri LTH2584, TMW1.112 and TMW1.656 versus lineage III strain L. reuteri LTH5448 (grey hatched). Differential enumeration was not possible for the strain combination L. reuteri LTH5448 and 100-23, therefore, only qPCR data is shown for this strain combination. Each competition was performed in doughs with 10 fermentation cycles that were back-slopped every 1, 2 and 3 days per fermentation cycle, respectively. The data was expressed as mean ± standard deviation from experiments performed in duplicate with two technical replicates.

Composition of fermentation microbiota in sourdoughs inoculated with the reutericyclin producing wild type strain L. reuteri TMW1.656 and the isogenic reutericyclin-negative and reutericyclin-sensitive L. reuteri TMW1.656ΔrtcNΔrtcT16.

The ratio of wild type strain to mutant strain was determined by qPCR analysis with strain-specific primers. Results are shown as means ± standard deviation of triplicate independent experiments.

Competition experiments between sourdough isolates of L. reuteri revealed that all strains that were used as inoculum were maintained over 10 fermentation cycles (Figure S3 of the online supplemental material). The competitiveness of the sourdough strains reflected the effects of lineage-specific metabolic traits on competitiveness in sourdough10,20. Glutamate decarboxylase mediates acid resistance; presence of this enzyme also increases competitiveness in sourdoughs with a long fermentation time10. Accordingly, the glutamate-decarboxylase-negative lineage I strains were more competitive in sourdoughs that were maintained by short fermentation cycles while the glutamate-decarboxylase positive lineage III strain L. reuteri LTH5448 was more competitive in sourdoughs that were maintained with 2 and 3 d cycles (Fig. 5).

Discussion

This study employed comparative genomics to demonstrate that the evolution of L. reuteri is shaped by positive selection of the core genome in addition to the gain and loss of accessory genes. Moreover, the identification of core genes under positive selection and the analysis of competitiveness in sourdough demonstrate that sourdough isolates of L. reuteri have adapted to the new habitat, or have been selected from a distinct subset of rodent lineage strains. This study provides new insights into the adaptation of L. reuteri to food and intestinal habitats, suggesting that these two habitats exert different selective pressure related to growth rate and metabolism.

Core genome phylogenetic analysis confirms host-specific lineages

Core genome phylogenetic analysis of the 16 strains of L. reuteri confirmed differentiation into host-specific lineages11. The rodent lineage III strains L. reuteri LTH2584, TWM1.112 and TWM1.656 were isolated form the same sourdough in 1988, 1994 and 1998, respectively. The phylogenetic relatedness of these strains suggested that the later isolates may be isolates of the same organism after 10 years of adaptation to sourdough fermentation6. However, successive contamination of the same sourdough with different strains of rodent origin is an alternative explanation for the isolation of highly related strains from the same sourdough.

Role of reutericyclin production for competitiveness in sourdoughs

Reutericyclin production may contribute to competitiveness of L. reuteri in sourdough3,6. This study demonstrated that a reutericyclin sensitive derivative of L. reuteri TMW1.656 and the reutericyclin producing wild type strain exhibited comparable competitiveness in sourdough, indicating that the ecological advantage of reutericyclin is about equivalent to the cost of reutericyclin production16,21. The reutericyclin gene cluster was acquired by horizontal gene transfer by few Lineage I and Lineage III sourdough isolates of L. reuteri6,16 and is thus unlikely to represent a sourdough-specific metabolic trait.

Evolution of the intestinal symbiont L. reuteri by horizontal gene transfer and positive selection

The evolution of pathogens is driven by gene loss, acquisition of genes by horizontal gene transfer and by positive selection of the core genome22,23,24. The relative contribution of recombination and positive selection are highly dependent on the species and the ecosystem. Only few genes were reported to be under positive selective pressure in the pathogenic Listeria monocytogenes24 while up to 34% and 92%, respectively, of the core genome were positively selected in specific lineages of the host-adapted genera Streptococcus and Campylobacter22,23. The evolution of the host adapted gut symbiont L. reuteri was previously attributed to gene loss and acquisition of lineage-specific accessory genes15. The congruent clustering of L. reuteri strains in the phylogenetic tree and the gene content tree confirms a major role of the gain or loss of host-specific metabolic and genetic traits in the evolution of the species14,15. This study additionally demonstrates that positive selection of the core genome shapes the evolution of L. reuteri. The expression of ribosomal proteins, rRNA and other transcription factors is regulated by the bacterial growth rate25 and a high density of ribosomal genes relates to rapid growth of L. sanfranciscensis in sourdough26. Positive selection in the functional category translation indicates that the intestinal ecological niches harbouring L. reuteri exert selective pressure for rapid growth. The proportion of the core genome that was under positive selection in L. reuteri matches the corresponding proportion in S. mutans23. S. mutans and L. reuteri are phylogenetically related host-adapted organisms colonizing the upper intestinal tract but contrast with respect to their impact on the hosts. S. mutant is a pathogen and L. reuteri is considered as probiotic but both species apparently use comparable ecological strategies for colonization and persistence16,27.

Reverse evolution or selection of L. reuteri in an extra-intestinal habitat?

The persistence of L. reuteri over 10 years in sourdough fermentation provides a unique opportunity to study the adaptation or selection of a host-specific gut symbiont to an extra-intestinal environment. Several lines of evidence suggest that SER sourdough isolates are distinct from intestinal strains. First, sourdough isolates cluster separately in the gene content tree, indicating that horizontal gene transfer and the loss of genes relates to the transition to sourdough16. Second, the functional categories “energy production and conversion” and “carbohydrate metabolism”, which are key elements for competitiveness in sourdough28,29, were significantly enriched among the positively selected genes in SER isolates. Third, sourdough isolates of L. reuteri displayed a higher relative fitness in sourdough when compared to rodent isolates. L. reuteri LTH5448 also achieved a high proportion of cell counts in competition with rodent isolates L. reuteri mlc3 and lpuph in experiments with 2 d fermentation time (data not shown). The differences in competitiveness of rodent and sourdough isolates, however, are smaller than differences between individual strains, reflecting the relatedness of the rodent forestomach and sourdough environments30. Because the time between sourdough contamination with L. reuteri and the isolation of the specific strains is unknown, it is not possible to discriminate whether the specific differences of the sourdough isolates reflect selection for a specific subset of rodent isolates, or “reverse evolution” of a gut symbiont to food fermentations.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that gene loss and gene gain as well as selective pressure on the core genome drive the evolution of L. reuteri. Remarkably, the gene content of sourdough isolates of L. reuteri differed from intestinal isolates and genes under positive selection in sourdough strains included maltose phosphorylase, alcohol dehydrogenase and lactate dehydrogenase, genes which are known to contribute to competitiveness in cereal fermentations. The study improves our understanding of the adaptation of bacteria to food fermentations as an evolutionary recent man-made habitat. It will also improve our ability to use food fermentations as model systems for more complex, intestinal ecosystems31.

Methods

Strains, media and growth conditions

The sourdough isolates L. reuteri LTH2584, TMW1.112, TMW1.656 and LTH54486,9,17 and the rodent isolates L. reuteri 100-23, mlc3 and lpuph32 were grown anaerobically at 37 °C in mMRS8. Sugars were autoclaved separately. Solid media contained additional 20 g agar per liter.

Whole-genome alignment and phylogenetics

Genome sequences of the 12 L. reuteri were retrieved from Genbank (Table S1). Genome sequences of sourdough isolates16 were re-annotated on the RAST server33 after gap closing by PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing. Primers binding to up- and down- stream locus of the target gap were selected after alignment of the genomes with Mauve34 and are shown in Table S1. Sequencing was performed by service of Macrogen Co. (Rockville, Maryland, USA).

All 16 genomes were aligned with Mugsy35. Homologous blocks present in each genome were concatenated with an in-house perl script. The most disordered regions were eliminated using Gblocks36. The disordered regions includes sites containing at least one gap and sites that are too divergent as they may not be homologous or may be saturated by multiple substitutions. The core genome size of L. reuteri was about 1.2 Mbp. A maximum-likelihood core genome tree was constructed using RaxML37. The tree was inferred under the general time-reversible nucleotide substitution model (GTR), with gamma-distributed rate heterogeneity of four rate categories (+Γ4) (Γ4). Bootstrap support values were calculated from 1000 replicates.

Gene clustering and construction of a gene content tree

Protein sequences longer than 50 amino acids from all genomes were combined and searched using BLAST with an all-against-all style with default parameters. The protein sequences with identities and coverage above 70% were clustered into families using the program orthoMCL38. The inflation value of 2 was used for the MCL clustering. Core genes were defined as those shared by all of the 16 strains; distributed genes as those shared by 2 to 15 strains and unique genes as those only contained in one strain.

A matrix of the presence or absence of each gene for each genome was created. A dissimilarity distance between genomes based on gene content (binary data for presence or absence of each protein family) measured by one minus the Jaccard coefficient (Jaccard distance) was calculated from this matrix39. A gene content tree was constructed using the hierarchical clustering (UPGMA) method based on these distances by MEGA40.

Analysis of positive selection

For each cluster of the single-copy core genes, protein sequences were aligned with MUSCLE41. These alignments were reverse-translated to codon-based nucleotide alignments by PAL2NAL42. Positive selection analysis based on each of these alignments was performed by CODEML implemented in PAML43. Nonsynonymous (amino acid altering) synonymous (silent) substitution ratios (ω), with ω = 1, < 1, or >1 indicate neutral, purifying, or positive selection, respectively. Positive selection was analysed on each family of core genes shared by all the 16 L. reuteri isolates using the site models M1a and M2a44,45. The model M1a (nearly neutral) allows all sites to be purifying selection (ω0 < 1) or neutral selection (ω0 = 1); the model M2a allows all sites to be positive selection (ω0 > 1). A likelihood ratio test (LRT) was carried out to infer the occurrence of sites subject to positive selective pressure through comparing M1a against M2a. Branch-site model and the one-ratio null model were used to analyze positive selection across the L. reuteri LTH2584/TWM1.112/TWM1.656 branch. Branch-site model allows ω to vary both among sites in the protein and across branches on the tree and aim to detect positive selection affecting a few sites along particular lineages (called foreground branches)46. Two models were used, the null model does not allow positive selection for the foreground branch and the alternative model assumes that the foreground branch may have some sites under positive selection. For the alternative model, three classes of ω (dN/dS) were defined: ω0 < 1, ω1 = 1 and ω2 ≥ 1, while in the null model, ω2 was fixed to 1. A likelihood ratio test (LRT) was carried out to infer positive selective pressure across the L. reuteri LTH2584/TWM1.112/TWM1.656 branch through comparing the results from these two models. The LRT statistic (twice the log-likelihood difference between the null and the alternative models) was compared with the chi-square distribution with 2 degrees of freedom for M2a vs. M1a and one degree of freedom for branch-site model vs. the null model.

For Clusters of Orthologous Groups of proteins (COG) analysis, we constructed a local COG database47 and then ran rpsblast using the sequence sets mentioned above as queries. We focused on the top three hits of each alignment and counted each category for comparison using in-house Perl script.

Competitiveness of L. reuteri in sourdough: experimental design

The persistence of strains was analyzed in back-slopped rye sourdough fermentations; experiments were carried out with fermentation times of 1, 2 and 3 days. Competition experiments were carried out with six strain combinations; sourdoughs were inoculated with L. reuteri LTH2584 and 100-23; L. reuteri LTH5448 and 100-23; L. reuteri LTH5448 and mlc3; L. reuteri LTH5448 and lpuph; L. reuteri LTH2584 and LTH5448; or L. reuteri LTH2584, TMW1.112, TMW1.656 and LTH5448.

Sourdough preparation and differential enumeration of cell counts

Competition experiments in sourdough were performed essentially as described10. In brief, sourdough was prepared by mixing 10 g rye flour with 10 ml of autoclaved tap water and 1 ml of bacterial inoculum. For binary and quaternary strain combinations, 0.5 and 0.25 mL, respectively, of the cell suspensions of individual strains were mixed to obtain 1 mL of bacterial cocktail as inoculum. Dough was fermented at 37 °C for 1, 2, or 3 days and back-slopped over 10 fermentation cycles. At each back-slopping step, 1 g of ripe sourdough from the previous cycle was mixed with 9.5 g of fresh rye flour and 9.5 ml of autoclaved tap water. The competition experiments were performed in duplicate and analyses were carried out with two technical replicates.

At each fermentation cycle, sourdoughs were analysed with respect to the pH, differential cell counts and qPCR with strain specific primers. Viable cell counts were enumerated by surface-plating of appropriate dilutions on mMRS agar. Individual strains were differentiated on the basis of the colony morphology. Differential enumeration was possible for the binary strain combinations L. reuteri LTH2584 vs. 100-23, L. reuteri LTH2584 vs. LTH5448, L. reuteri LTH5448 vs. mlc3 and L. reuteri LTH5448 vs. lpuph, but not for L. reuteri LTH5448 vs. 100-23. In the quaternary strain combination, the combined total of L. reuteri LTH2584, TMW1.112 and TMW1.656 was differentiated from L. reuteri LTH5448.

Analysis of sourdough microbiota by qPCR

Total DNA was isolated from sourdough48 and gene copy numbers of L. reuteri were quantified by strain-specific qPCR. Strain-specific primers are listed in Table 1. Standard curves to convert detection threshold cycles to gene copy numbers were established by analysis of 10-fold serial dilutions of target DNA of known concentration. The strain-specific primers to for strain specific quantification are shown in Table 1.

Calibration curves to convert gene copy numbers to cell counts in sourdough were Calibration curves to convert gene copy numbers to cell counts in sourdough were established with sourdoughs that were fermented with single strains. Samples were mixed with 2 volumes of sterile saline and serially diluted with saline. From each of the dilutions, cell counts were determined by further dilution and surface plating and the gene copy numbers were quantified by qPCR as described above. Calibration curves were established in duplicate after 1 and 3 d of fermentation (Figure S2).

Quantitative PCR analyses were carried out in duplicate in MicroAmp Fast Optical 96-well reaction plates capped with MicroAmp Optical Adhesive Film (Applied Biosystems, Burlington, ON, Canada). The PCR reaction mixture consisted of 12.5 μl Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), 0.4 μM of each primer (Table S1), 2 μl of template DNA and sterile Milli-Q water to final volume of 25 μl. Melting curves were obtained by a stepwise increase of the temperature from 60 to 95 °C at 0.05 °C/s) and melting-curve data were analyzed to verify amplification of the correct targeted PCR products. The detection limit was 102 copy numbers/g sourdough for the strain-specific primers.

Competitiveness of isogenic reutericyclin-positive and reutericyclin-negative and reutericyclin-sensitive isogenic strains of L. reuteri

Competition experiment between reutericyclin-positive wild type strain L. reuteri TMW1.656 and its reutericyclin-susceptible mutant L. reuteri TMW1.656ΔrtcNΔrtcT16 were performed using white wheat flour with a dough yield of 200. Sourdough was propagated every 24h with 1% inoculum for 5 days. The ratio of wild type to mutant strains at the end of each fermentation cycle was determined by qPCR with primers listed in Table 1.

Calculation of the relative fitness of strains of L. reuteri in sourdough

The differential cell counts and the strain-specific gene copy numbers were used to calculate the relative fitness of the respective strains of L. reuteri. The fitness (w) of strain x relative to that of strain y was calculated based an equation derived from49:

where x0 and y0 denote the strain specific cell densities or gene copy numbers at the beginning of each fermentation cycle and xF and yF are cell densities at the end of each of fermentation cycle. For each competition experiment, the relative fitness was plotted as average of 20 replicates (replicate experiments with 10 fermentation cycles each).

Additional Information

Accession numbers: The re-annotated genomes of L. reuteri TMW1.112 and TMW1.656 are deposited with the Genebank accession number.

How to cite this article: Zheng, J. et al. Comparative genomics Lactobacillus reuteri from sourdough reveals adaptation of an intestinal symbiont to food fermentations. Sci. Rep. 5, 18234; doi: 10.1038/srep18234 (2015).

References

Gänzle, M. G. Lactic metabolism revisited: Metabolism of lactic acid bacteria in food fermentations and food biotechnology. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2, 106–117 (2015).

Walter, J. Ecological role of lactobacilli in the gastrointestinal tract: implications for fundamental and biomedical research. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 4985–4996 (2008).

Vogel, R. F. et al. Non-dairy lactic fermentations: The cereal world. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 76, 403–411 (1999).

Oh, P. L. et al. Diversification of the gut symbiont Lactobacillus reuteri as a result of host-driven evolution. ISME J. 4, 377–387 (2010).

Spinler, J. K. et al. From prediction to function using evolutionary genomics: human-specific ecotypes of Lactobacillus reuteri have diverse probiotic functions. Genome Biol. Evol. 6, 1772–1789 (2014).

Gänzle, M. G. & Vogel, R. F. Contribution of reutericyclin production to the stable persistence of Lactobacillus reuteri in an industrial sourdough fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 80, 31–45 (2002).

Sekwati-Monang, B. & Gänzle, M. G. Microbiological and chemical characterisation of ting, a sorghum-based sourdough product from Botswana. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 150, 115–121 (2011).

Meroth, C. B., Walter, J., Hertel, C., Brandt, M. J. & Hammes, W. P. Monitoring the bacterial population dynamics in sourdough fermentation processes by using PCR-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 475–482 (2003).

Böcker, G., Stolz, P. & Hammes, W. P. Neue Erkenntnisse zum Ökosystem Sauerteig und zur Physiologie der sauerteigtypischen Stämme Lactobacillus sanfrancisco und Lactobacillus pontis. Getreide Mehl Brot 49, 370–374 (1995).

Lin, X. B. & Gänzle, M. G. Effect of lineage-specific metabolic traits of Lactobacillus reuteri on sourdough microbial ecology. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 5782–5789 (2014).

Su, M. S. W., Oh, P. L., Walter, J. & Gänzle, M. G. Intestinal origin of sourdough Lactobacillus reuteri isolates as revealed by phylogenetic, genetic and physiological analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 6777–6780 (2012).

Wilson, C. M. et al. Lactobacillus reuteri 100-23 modulates urea hydrolysis in the murine stomach. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 6104–6113 (2014).

Su, M. S. & Gänzle, M. G. Novel two-component regulatory systems play a role in biofilm formation of Lactobacillus reuteri rodent isolate 100-23. Microbiology 160, 795–806 (2014).

Frese, S. A. et al. Molecular characterization of host-specific biofilm formation in a vertebrate gut symbiont. PLoS Genet. 9:e1004057 (2013).

Frese, S. A. et al. The evolution of host specialization in the vertebrate gut symbiont Lactobacillus reuteri. PLoS Genet. 7, e1001314 (2011).

Lin, X. B. et al. Genetic determinants of reutericyclin biosynthesis in Lactobacillus reuteri. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 2032–2041 (2015).

Schwab, C. & Gänzle, M. G. Effect of membrane lateral pressure on the expression of fructosyltransferases in Lactobacillus reuteri. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 29, 89–99 (2006).

Morita, H. et al. Comparative genome analysis of Lactobacillus reuteri and Lactobacillus fermentum reveal a genomic island for reuterin and cobalamin production. DNA Res. 15, 151–161 (2008).

Zhang, C. & Gänzle, M. G. Metabolic pathway of α-ketoglutarate in Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis and Lactobacillus reuteri during sourdough fermentation. J. Appl. Microbiol. 109, 1301–1310 (2010).

Su, M. S. W., Schlicht, S. & Gänzle, M. G. Contribution of glutamate decarboxylase in Lactobacillus reuteri to acid resistance and persistence in sourdough fermentation. Microb. Cell Factories 10 (Suppl 1), S8 (2011).

Abrudan, M. I., Brown, S. & Rozen, D. E. Killing as means of promoting biodiversity. Biochem Soc. Trans. 40, 1512–1516 (2012).

Lefébure, T. & Stanhope, M. J. Pervasive, genome-wide positive selection leading to functional divergence in the bacterial genus Campylobacter. Genome Res. 19, 1224–1232 (2009).

Lefébure, T. & Stanhope, M. J. Evolution of the core and pan-genome of Streptococcus: positive selection, recombination and genome composition. Genome Biol. 8, R71 (2007).

Orsi, R. H., Sun, Q. & Wiedmann, M. Genome-wide analyses reveal lineage specific contributions of positive selection and recombination to the evolution of Listeria monocytogenes. BMC Evol. Biol. 8, 233 (2008).

Klumpp, S., Zhang, Z. & Hwa, T. Growth rate-dependent global effects on gene expression in bacteria. Cell 139, 1366 1375

Vogel, R. F. et al. Genomic analysis reveals Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis as stable element in traditional sourdoughs. Microb Cell Fact. 10 Suppl 1, S6 (2011).

Gänzle, M. G. & Schwab, C. [Ecology of exopolysaccharide formation by lactic acid bacteria: Sucrose utilization, stress tolerance and biofilm formation] Bacterial polysaccharides. Current innovations and future trends. [ Ullrich, M. (Ed.)][263–278](Caister Academic Press: Norfolk,, 2009).

Gänzle, M. G., Vermeulen, N. & Vogel, R. F. Carbohydrate, peptide and lipid metabolism of lactobacilli in sourdough. Food Microbiol. 24, 128–138 (2007).

Passerini, D. et al. The carbohydrate metabolism signature of Lactococcus lactis strain A12 reveals its sourdough ecosystem origin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 5844–5852 (2013).

Schwab, C., Tweit, A. T., Schleper, C. & Urich, T. Gene expression of lactobacilli in murine forestomach biofilms. Microb. Biotechnol. 7, 347–359 (2014).

Wolfe, B. E. & Dutton, R. J. Fermented foods as experimentally tractable microbial ecosystems. Cell 161, 49–55 (2015).

Wesney, E. & Tannock, G. W. Association of rat, pig and fowl biotypes of lactobacilli with the stomach of gnotobiotic mice. Microb. Ecol. 5, 35–42 (1979).

Aziz, R. K. et al. The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics 9, 75 (2009).

Darling, A. C., Mau, B., Blattner, F. R. & Perna, N. T. Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 14, 1394–1403 (2004).

Angiuoli, S. V. & Salzberg, S. L. Mugsy: fast multiple alignment of closely related whole genomes. Bioinformatics 27, 334–342 (2010).

Talavera, G. & Castresana, J. Improvement of phylogenies after removing divergent and ambiguously aligned blocks from protein sequence alignments. Syst. Biol. 56, 564–577 (2007).

Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30, 1312–1313 (2014).

Li, L., Stoeckert, C. J. Jr. & Roos, D. S. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 13, 2178–2189 (2003).

Wolf, Y. I., Rogozin, I. B., Grishin, N. V. & Koonin, E. V. Genome trees and the tree of life. Trends Genet. 18, 472–479 (2002).

Tamura, K., Stecher, G., Peterson, D., Filipski, A. & Kumar, S. MEGA6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–2729 (2013).

Edgar, R. C. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797 (2004).

Suyama, M., Torrents, D. & Bork, P. PAL2NAL: robust conversion of protein sequence alignments into the corresponding codon alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 34 (Web Server issue), W609–612 (2006).

Yang, Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1586–1591 (2007).

Wong, W. S., Yang, Z., Goldman, N. & Nielsen, R. Accuracy and power of statistical methods for detecting adaptive evolution in protein coding sequences and for identifying positively selected sites. Genetics 168, 1041–1051 (2004).

Yang, Z., Wong, W. S. & Nielsen, R. Bayes empirical bayes inference of amino acid sites under positive selection. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22, 1107–1118 (2005).

Zhang, J., Nielsen, R. & Yang, Z. Evaluation of an improved branch-site likelihood method for detecting positive selection at the molecular level. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22, 2472–2479 (2005).

Tatusov, R. L. et al. The COG database: an updated version includes eukaryotes. BMC Bioinformatics 4, 41 (2003).

Lin, X. B. & Gänzle, M. G. Quantitative high-resolution melting PCR analysis for monitoring of fermentation microbiota in sourdough. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 186, 42–48 (2014).

Kerr, B., Riley, M. A., Feldman, M. W. & Bohannan, B. J. M. Local dispersal promotes biodiversity in a real-life game of rock–paper–scissors. Nature 418, 171–174 (2002).

Acknowledgements

Xin Zhao acknowledges support from the China Scholarship Council; Michael Gänzle acknowledges support from the Canada Research Chairs Program. The Alberta Livestock and Meat Agency is acknowledged for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.S.Z., X.Z. and X.B.L. performed and analysed experiments; M.G.G. and J.S.Z. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, J., Zhao, X., Lin, X. et al. Comparative genomics Lactobacillus reuteri from sourdough reveals adaptation of an intestinal symbiont to food fermentations. Sci Rep 5, 18234 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep18234

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep18234

This article is cited by

-

Galacto-oligosaccharide preconditioning improves metabolic activity and engraftment of Limosilactobacillus reuteri and stimulates osteoblastogenesis ex vivo

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Bioinformatics and its role in the study of the evolution and probiotic potential of lactic acid bacteria

Food Science and Biotechnology (2023)

-

The periodic table of fermented foods: limitations and opportunities

Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology (2022)

-

Genomic analysis of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157:H7 from cattle and pork-production related environments

npj Science of Food (2021)

-

Characterization of γ-glutamyl cysteine ligases from Limosilactobacillus reuteri producing kokumi-active γ-glutamyl dipeptides

Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.