Abstract

Both amyloid-β (Aβ) and transition metal ions are shown to be involved in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), though the importance of their interactions remains unclear. Multifunctional molecules, which can target metal-free and metal-bound Aβ and modulate their reactivity (e.g., Aβ aggregation), have been developed as chemical tools to investigate their function in AD pathology; however, these compounds generally lack specificity or have undesirable chemical and biological properties, reducing their functionality. We have evaluated whether multiple polyphenolic glycosides and their esterified derivatives can serve as specific, multifunctional probes to better understand AD. The ability of these compounds to interact with metal ions and metal-free/-associated Aβ and further control both metal-free and metal-induced Aβ aggregation was investigated through gel electrophoresis with Western blotting, transmission electron microscopy, UV-Vis spectroscopy, fluorescence spectroscopy and NMR spectroscopy. We also examined the cytotoxicity of the compounds and their ability to mitigate the toxicity induced by both metal-free and metal-bound Aβ. Of the polyphenols investigated, the natural product (Verbascoside) and its esterified derivative (VPP) regulate the aggregation and cytotoxicity of metal-free and/or metal-associated Aβ to different extents. Our studies indicate Verbascoside represents a promising structure for further multifunctional tool development against both metal-free Aβ and metal-Aβ.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a growing concern for global public health, spurred on, in part, by a lack of effective treatments or cures1. While potential therapeutics have been developed for AD, their clinical success has been hindered by a limited molecular level understanding of the disease’s etiology2,3,4. AD is commonly considered a protein misfolding disease characterized by the presence of protein aggregates, including senile plaques composed primarily of amyloid-β (two main Aβ forms, Aβ40 and Aβ42)4,5,6. Aβ undergoes a progressive aggregation process, advancing from a small, intrinsically disordered peptide to intermediate oligomers of various sizes and structures, finally forming extended fibers; individual aggregates are believed to have varying degrees of toxicity and relevance in AD4,6,7.

The senile plaques in the AD-affected brain have also been shown to contain elevated concentrations of transition metals, specifically Cu, Zn and Fe, which suggests that these metal ions interact with and alter the aggregation of Aβ 4,8,9,10. Understanding the interactions between metal ions and Aβ in vitro could help elucidate potentially toxic mechanisms of both factors in AD10,11,12. These metal ions could accelerate the aggregation of Aβ while simultaneously generating a variety of aggregates which may have biological functions distinct from those formed in the absence of metals9,10. Additionally, the binding of Aβ to redox active metals (i.e., Cu) can facilitate redox cycling and lead to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) resulting in an oxidative stress environment, a known characteristic of the AD-afflicted brain12,13,14. The effects of these interactions in vivo remain unclear, however; in-depth understanding is hindered by the multifactorial nature of the disease which makes it difficult to identify and quantify the influence of any of the potentially causative agents.

The application of chemical probes which can modulate the various factors associated with AD (e.g., Aβ, metal ions) may advance our understanding of the disease and uncover different toxic factors by isolating individual potential culprits. Unfortunately, there remains a lack of understanding about the relationship between small molecules and their subsequent biological functions with regards to the multiple aspects associated with AD. It is believed that hydrophobic interactions drive early stages of Aβ aggregation and that compounds with similarly hydrophobic regions may effectively disrupt these aggregation-promoting forces and act as modulators of amyloid formation; some compounds of this nature have been investigated previously6. It is unclear, though, which chemical moieties on these compounds may be the most potent at altering this process. To increase the specificity of anti-amyloidogenic compounds, multifunctional compounds have been designed to target and modulate additional aspects associated with AD (i.e., metal-associated Aβ (metal–Aβ), ROS) along with metal-free Aβ simultaneously15,16,17. Compounds known to interact with Aβ have been appended with known metal binding moieties to generate molecules capable of targeting both metal-free Aβ and metal–Aβ and these multifunctional compounds have demonstrated an ability to modulate both factors to differing extents15,16. As was the case with Aβ interaction, however, rational design of these metal binding moieties is hindered by a limited understanding of how these chelating agents function in the complex AD environment. Additionally, while it is desirable for compounds to also mediate oxidative stress, both through the modulation of ROS and free radicals, this function is similarly difficult to rationally incorporate into a structural entity. Efforts have previously been made to design multifunctional compounds for investigating the role of metal-free Aβ, metal-Aβ and ROS in AD18, but the advancements in the field are generally slowed by limited information on the structure-function relationships between small molecules and their ability to regulate these disease-related features.

In order to gain better insight to this complex disease and to broaden current understanding of the connection between chemical structure and its function in the presence of factors associated with AD, three naturally occurring polyphenolic glycosides (Phlorizin, Verbascoside and Rutin; Fig. 1) were chosen for a selective reactivity study towards both metal-free Aβ and metal-Aβ. The investigation of naturally occurring compounds gives the substantial advantage of a minimal toxicity profile and a significant amount of background information from traditional medicine. Natural polyphenolic products have been previously shown to possess potential anti-amyloidogenic activity19,20. Both Verbascoside and Rutin have demonstrated the capacity to alter the aggregation and toxicity of metal-free Aβ aggregation towards nontoxic species21,22,23,24 and phloretin, the non-glycosidic version of Phlorizin, has exhibited an ability to prevent membrane-associated aggregation of Aβ25. While these preliminary studies examined aggregation in the absence of metal ions, the presence of known metal interaction moieties, phenol and catechol groups in Phlorizin and Verbascoside/Rutin, respectively, suggests that these compounds may be capable of simultaneously interacting with both Aβ and metal ions26,27,28,29. Furthermore, all three compounds are known antioxidants, indicating that they could also help mitigate oxidative stress associated with the AD-affected brain30,31,32. Finally, these compounds are naturally glycosylated, which has been proposed to improve bioavailability and distribution in the brain33,34,35, as well as redirect the folding of metal-free Aβ species36,37. Combined, these structural and chemical features suggest that Phlorizin, Verbascoside and Rutin possess unique chemical features desirable for a probe to target multiple factors (i.e., metal-free and metal-bound Aβ) and mitigate their toxicity leading to AD.

Chemical structures of glycosylated polyphenols and their derivatives.

Phlorizin, 1-(2,4-dihydroxy-6-(((2S,3R,4S,5S,6R)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)phenyl)-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)propan-1-one; Verbascoside, (2R,3R,4R,5R,6R)-6-(3,4-dihydroxyphenethoxy)-5-hydroxy-2-(hydroxymethyl)-4-(((2S,3R,4R,5R)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-methyltetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3-yl (E)-3-(3,4-dihydroxy phenyl)acrylate; Rutin, 2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-5,7-dihydroxy-3-(((2S,3R,4S,5S,6R)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-((((2R,3R,4R,5R,6S)-3,4,5-trihydroxytetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)methyl)tetra hydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)-4H-chromen-4-one; F2, (2S,3R,4S,5R,6R)-2-(3,5-dihydroxy-2-(3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)propanoyl)phenoxy)-6-((propionyloxy)methyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3,4,5-triyl tripropionate; VPP, (2S,3R,4R,5S,6S)-2-(((2R,3R,4S,5R,6R)-2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenethoxy)-5-(((E)-3-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)acryloyl)oxy)-3-(propionyloxy)-6-((propionyloxy)methyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-4-yl)oxy)-6-methyltetrahydro-2H-pyran-3,4,5-triyl tripropionate; R2, (2R,3R,4R,5S,6S)-2-(((2R,3R,4S,5R,6S)-6-((2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-5,7-dihydroxy-4-oxo-4H-chromen-3-yl)oxy)-3,4,5-tris(propionyloxy)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)methoxy)-6-methyl tetrahydro-2H-pyran-3,4,5-triyl tripropionate.

To provide insight into structure-activity relationships, selectively esterified derivatives, F2, VPP and R2 (Fig. 1), were prepared and investigated alongside their parent compounds30,31,32. Esterification could provide multiple benefits in the quest for an effective multifunctional probe while also acting as a general proof of concept that a prodrug approach is a viable method in the search for molecular tools in AD research. Ester formation may improve trafficking across lipid bilayers and facilitate targeted delivery of unprotected compounds within cells following cleavage by esterases; for these reasons, it is a commonly used modification in prodrug design38. The ester groups may also improve the ability of the compounds to passively diffuse across the blood brain barrier (BBB) due to greater lipophilicity16,33. Finally, the increased hydrophobicity could promote interactions between the compounds and the more aggregation prone regions of the Aβ sequence, which are similarly hydrophobic4. Overall, we believe that esterification may tune the ability of these three compounds to interact with both metal-free Aβ and metal–Aβ species while simultaneously improving the bioavailability, making them more suitable for future in vivo applications than their non-esterified counterparts. Using these six compounds, we aim to further expand the understanding of structure-function relationships between multifunctional probes towards both metal-free Aβ and metal-Aβ through a detailed, molecular level characterization.

Results

Influence of Polyphenols on Metal-Free and Metal-Induced Aggregation In Vitro

Initially, to investigate the effects of the six polyphenols (Fig. 1) on the structure and formation of both metal-free Aβ and metal–Aβ aggregation pathways, disaggregation (Figs 2 and 3 and S1) and inhibition (Fig. S2) experiments were performed. Both the more prevalent Aβ40 and the more aggregation-prone Aβ42 isoforms were employed in both inhibition and disaggregation studies4. For disaggregation experiments, Aβ was allowed to aggregate in either the absence or presence of either CuCl2 or ZnCl2 for 24 h to form aggregated species. The compounds were then added to these aggregates and incubated for either 4 or 24 h to determine their ability to redirect the size and structure of pre-aggregated Aβ species. In inhibition experiments, Aβ (for metal-Aβ samples, Aβ samples were treated with CuCl2 or ZnCl2) and the compounds were incubated for either 4 or 24 h to identify how they are capable of modulating the early steps in aggregation of both metal-free Aβ and metal-Aβ. Gel electrophoresis with Western blot (gel/Western blot) using an anti-Aβ antibody (6E10) and TEM were utilized to visualize the size distribution and morphology, respectively, of the resultant Aβ species upon treatment with polyphenols in the absence and presence of metal ions for both disaggregation and inhibition experiments18,39.

Modulation of preformed, metal-free and metal-induced Aβ40 aggregates by Phlorizin, F2, Verbascoside, VPP, Rutin, or R2.

A scheme of sample preparation for disaggregation experiments with Aβ40 (top). (a) Analysis of the resultant Aβ40 species by gel electrophoresis using Western blotting with an anti-Aβ antibody (6E10). (b) TEM images of the morphologies of the resultant Aβ species from the samples that were incubated for 24 h. Experimental conditions: [Aβ40] = 25 μM; [CuCl2 or ZnCl2] = 25 μM; [compound] = 50 μM; 4 or 24 h incubation; pH 6.6 (for Cu(II) samples) or pH 7.4 (for metal-free and Zn(II) samples); 37 °C; constant agitation.

Influence of Phlorizin, F2, Verbascoside, VPP, Rutin, or R2 on pre-generated metal-free and metal-induced Aβ42 aggregates.

A scheme of sample preparation for disaggregation experiments with Aβ42 (top). (a) Analysis of the resultant Aβ42 species by gel electrophoresis using Western blot with an anti-Aβ antibody (6E10). (b) TEM images of the morphologies of the resultant Aβ species from the samples that were incubated for 24 h. Experimental conditions: [Aβ42] = 25 μM; [CuCl2 or ZnCl2] = 25 μM; [compound] = 50 μM; 4 or 24 h incubation; pH 6.6 (for Cu(II) samples) or pH 7.4 (for metal-free and Zn(II) samples); 37 °C; constant agitation.

Neither Phlorizin nor F2 demonstrated a significant ability to interact with metal-free Aβ or metal–Aβ species in either a disaggregatory or inhibitory manner. In disaggregation experiments, gel/Western blot revealed that neither of these compounds was able to transform preformed Aβ aggregates regardless of Aβ isoforms or metal presence (Figs 2a and 3a, lanes 2 and 3). Phlorizin did appear to slightly change the morphology of species to marginally more disordered than untreated fibrils; however, large and extended Aβ aggregates were observed with and without metal ions (Fig. S1). A similar lack of reactivity was observed in inhibition experiments (Fig. S2, lanes 2 and 3). These two compounds appear unable to influence Aβ40 and Aβ42 aggregation behaviors regardless of the presence or absence of metal ions.

Both Rutin and R2 showed mild reactivity with metal-free Aβ and/or metal–Aβ. Under disaggregation conditions, R2 produced low MW aggregates of Aβ40 (<15 kDa) after 4 h in the absence of metal ions; after 24 h in the absence of metal ions, both Rutin and R2 triggered relatively low MW aggregates (<35 kDa) (Fig. 2a, lanes 6 and 7). The morphology of these species was slightly more compact that that of untreated Aβ40 aggregates (Fig. S1). A relatively similar range of Aβ40 aggregates was generated by both Rutin and R2 when CuCl2 was present, after 24 h (Fig. 2a) and their morphology was even more compact than in the absence of metal ions (Fig. S1). Neither Rutin nor R2 appeared to have any impact on preformed Zn(II)–Aβ40 aggregates. The two compounds displayed a minimal or no effect upon preformed Aβ42 aggregates, regardless of the presence or absence of metal ions (Fig. 3a, lanes 6 and 7). Rutin and R2 presented a modest ability to redirect Cu(II)-induced aggregation of Aβ40 or Aβ42 after 24 h incubation in inhibition studies (Fig. S2, lanes 6 and 7). This suggests that both compounds have mild reactivity towards preformed Aβ aggregates, favoring those formed in the presence of CuCl2.

Unlike the other four compounds, both Verbascoside and VPP were able to control Aβ40 and Aβ42 aggregation, though to different extents. When preformed, metal-free Aβ40 aggregates were treated with VPP for 4 h, a wide MW range (10–260 kDa) of species was formed (Fig. 2a, lane 5). These species were still observed after 24 h incubation. Verbascoside, the non-esterified parent compound of VPP, did not indicate any reactivity against preformed metal-free Aβ40 aggregates. Both compounds did demonstrate an ability to disaggregate Cu(II)–Aβ40 aggregates, however (Fig. 2, lanes 4 and 5). At the early incubation time point (i.e., 4 h) the two compounds mainly generated relatively low MW (<35 kDa) aggregates, evident by gel/Western blot. At the later incubation time point (i.e., 24 h), both compounds were capable of producing much wider MW ranges of Cu(II)–Aβ40 species (Fig. 2a, lanes 4 and 5). In the case of Zn(II)-containing aggregates; the initial disaggregation by Verbascosde and VPP was slower still. The Aβ40 sample treated with Verbascoside for 24 h exhibited smaller-sized species while VPP triggered a wider range of aggregates, similar to that observed in both the absence of metals and the presence of Cu(II) (Fig. 2a). For all aggregates, both Verbascoside and VPP were able to convert large extended fibrils into smaller, generally amorphous structures (Fig. 2b). This same reactivity trend was observed when Verbascoside and VPP were added to metal-free and metal-associated, preformed Aβ42 aggregates (Fig. 3). These compounds were capable of slightly altering Aβ42 aggregates in the absence of metal ions. Additionally, VPP generated various-sized aggregates of Zn(II)–Aβ42 after 4 h only, a process which required 24 h with Aβ40 (Fig. 3a). Similar to Aβ40, unstructured Aβ42 aggregates induced by treatment with the two compounds were shown by TEM (Fig. 3b).

Verbascoside and VPP also displayed reactivity towards Aβ40 and Aβ42 in inhibition experiments (Fig. S2, lanes 4 and 5). Only VPP affected the aggregation of metal-free Aβ40/Aβ42, which was evident just after 4 h with both isoforms. Both Verbascoside and VPP demonstrated inhibitory activity towards metal-Aβ40/Aβ42. In the presence of Cu(II), the two compounds promoted a variety of aggregates to different extents after 4 h incubation; Verbascoside generated a smaller MW range of aggregates than VPP, suggesting that their activity may be size and/or conformation dependent. A similar trend in Aβ aggregate size was observed in the presence of Zn(II) when Verbascoside and VPP were introduced (Fig. S2). Verbascoside and VPP presented the similar time dependence in the presence of Zn(II) for the inhibition of Aβ40 aggregation as they did with Aβ40 disaggregation; their reactivity towards Zn(II)–Aβ40 was noticeable only after 24 h (Fig. S2a). This suggests that the timescale of reactivity may be dependent upon solution conditions, specifically the metal(s) present in solution and the morphology of aggregates, at a given time. Taken together, the results from these disaggregation and inhibition experiments suggest that Verbascoside and VPP have a distinct capacity to modulate the aggregation of metal–Aβ (as well as metal-free Aβ mainly in the case of VPP) which is generally absent for the other four compounds analyzed in this study. It is interesting to observe that among the selected polyphenols the reactive Verbascoside and VPP both feature distinctive double catechol moieties, bearing the two characteristic ortho-hydroxy groups. Meanwhile, Rutin and R2 which only show mild reactivity have a single catechol moiety. Phloririzin and F2 have no catechol moieties while also presenting no noticeable reactivity with Aβ species. This points to a potential role for the catechol moiety in the activity of these compounds. Additionally, from this set of compounds, it appears that structural modification of the sugar moiety (i.e., selective esterification) can drastically alter the function of the parent compound, as was seen for both Verbascoside/VPP and Rutin/R2.

Metal Binding Properties of Polyphenols

In order to elucidate the molecular level interactions responsible for the varied anti-amyloidogenic activity of the polyphenols towards metal–Aβ species (vide supra), it is necessary to understand the potential binding of each compound with the component parts of system: metal ions and Aβ monomers/aggregates. The potential interaction between the polyphenols and metal ions was investigated first. The OH groups found on the aromatic rings of all six compounds could potentially interact with transition metals; the catechol moieties of Verbascoside, VPP, Rutin and R2 are especially likely to bind metal ions in a manner similar to previously reported polyphenols20,28,40,41,42. It has already been suggested that both Verbascoside and Rutin could interact with Cu(II) in solution43,44,45. The Cu(II) binding properties of Phlorizin/F2, Verbascoside/VPP and Rutin/R2 were examined by UV-Vis while the Zn(II) binding of Verbascoside and VPP was monitored by 1H NMR due to a lack of significant optical changes in the spectra when the ligand was treated with Zn(II) (Fig. 4, S3 and S4).

Metal binding studies of Verbascoside and VPP.

(a) Cu(II) binding studies of Verbascoside (Verb) and VPP by UV-Vis. Samples were incubated for 2 h with or without Cu(II) (0.5–10 equiv) at pH 7.4 at room temperature. (b) Zn(II) binding studies of Verbascoside (top) and VPP (bottom) by 1H NMR. The samples of compounds (2 mM) were titrated with ZnCl2 (0, 2 and 10 equiv) in DMSO-d6 at room temperature.

The UV-Vis spectra of the six polyphenols showed different levels of spectral changes following the titration of CuCl2 in buffered aqueous solution (pH 7.4; Fig. 4a and S3). Addition of CuCl2 to both Verbascoside and VPP in solution induced a slight change in the absorption bands at ca. 330 nm and 405 nm, implying potential interaction between the catechol moieties of both ligands and Cu(II) in solution (Fig. 4a)46. The spectral change is more drastic in VPP than in Verbascoside, which suggests that esterification of the OH groups in the sugar ring could reduce their competitive interaction with Cu(II) and promote binding by the catechol moieties. Neither compound presented significantly noticeable spectral shifts indicative of complex formation, however, suggesting that interaction of either Verbascoside or VPP with Cu(II) in solution could be weak. Previous studies on complex formation between Verbascoside and Cu(II) are unclear about the extent of complex formation, which indicates that the complex formation could depend upon experimental conditions (i.e., buffer, salt concentration, pH)43,47. Addition of CuCl2 to solutions of either Phlorizin or F2 induced no significant shift in spectral features, possibly due to the minimal interaction of the phenol moiety in the compounds for Cu(II) in solution (Fig. S3). The presence of Cu(II) did induce modest changes in the spectrum of Rutin, including a decrease in the primary peak at ca. 330 nm and an increase in a shoulder at ca. 425 nm (Fig. S3). This may be caused by the interaction between the catechol moiety and Cu(II). These shifts are similar, though of smaller magnitude, to those previously observed for Rutin-Cu(II) complexes44,45. Finally, R2 exhibited slight spectral changes over the course of the titration, suggesting minimal or no interaction with Cu(II) in solution (Fig. S3), suggesting that esterification of Rutin could change the interaction between the ligand and Cu(II). These results suggest that only Verbascoside, VPP and Rutin have an observable ability to interact with Cu(II) under the conditions of this study.

The interaction of Verbascoside and VPP with Zn(II) was also investigated by 1H NMR in DMSO-d6 (Fig. 4b). When Zn(II) was titrated into Verbascoside up to 2 equiv, all phenolic protons exhibited minor sharpening while titration up to 10 equiv resulted in selective broadening of the resonances associated with the caffeic acid moiety. The hydroxytyrosine phenolic protons showed minimal change upon addition of more Zn(II). Selective broadening suggests that Zn(II) preferentially associates with the catechol moiety in caffeic acid which causes proton exchange with residual water present in the solvent. A similar pattern was observed when Zn(II) was added to VPP. During the titration of VPP, the protons of the catechol group in caffeic acid broadened, suggesting interaction with the metal and subsequent proton exchange with the residual aqueous solvent. No other proton resonances demonstrate any shifts or broadening over the course of the titration for either compound (Fig. S4). This would suggest that in both Verbascoside and VPP, Zn(II) is observed to relatively weakly interact with the phenolic protons of the caffeic acid moiety over all other portions of the compounds, though weakly. Overall, both Verbascoside and VPP are shown to interact with both Cu(II) and Zn(II) with a modest affinity under the conditions employed in this study, implying that direct interaction with the metal ions could be partially responsible for the ability of these compounds to redirect metal–Aβ aggregation (vide supra). This is likely not the direct result of metal chelation, however, given the relatively strong affinity of Aβ for both metal ions10.

Interaction of Polyphenols with Multiple Aβ Forms

Given the ability of both Verbascoside and VPP to redirect the morphology and aggregation of Aβ, the direct interaction of the two, along with both Phlorizin and R2, with monomeric Aβ40 was investigated (Fig. 5 and S5). 2D band-Selective Optimized-Flip-Angle Short-Transient Heteronuclear Multiple Quantum Coherence (SOFAST-HMQC) NMR experiments were performed to identify potential residue-specific interactions between monomeric Aβ peptide and the compounds48. The chemical shift perturbation (CSP) for each resolvable residue was calculated by comparing the spectrum of ligand-free Aβ40 with that of Aβ40 in the presence of excess ligand (10 equiv) and these CSP values were compared to the average CSP values (Figs 5a, 5b and S4) to identify potentially favored interactions20,28. All four compounds induced some mild to moderate (0.02–0.035 ppm) chemical shifts in varying regions of the peptide. Verbascoside (Fig. 5c) triggered a relatively distinct shift in D23 and also weakly perturbed Q15 while VPP (Fig. 5d) caused some shifts in Y10, E11, Q15, or F20. The interactions of Verbascoside seem to favor both polar and charged residues that are centrally located in the sequence, suggesting that both dipole-dipole interactions and hydrogen bonding could direct potential ligand binding. VPP, however, perturbed a mixture of hydrophobic and hydrophilic residues, suggesting that the added acyl groups could encourage some nonpolar contacts during ligand interaction with Aβ. π–π stacking between VPP and the aromatic side chains of Y10 and/or F20 could also be responsible for the observed shifts. Despite causing shifts in unique residue resonances, both compounds alter residues near the purported metal binding site of Aβ (residues 1–16) suggesting that the compounds preferentially interact with the N-terminus and may be oriented in a manner which promotes interaction with metal ions when present in solution or could alter the conformation of the N-terminus of the peptide, disrupting the peptide’s ability to bind metal ions4,8,9,10. Phlorizin (Fig. 5e) caused minor chemical shifts in both the hydrophobic core (F19-A21) and the C-terminus (V36); nonpolar forces may be responsible for any prospective Phlorizin–Aβ40 interaction. Rutin (Fig. 5f) prompted small shifts in regions similar to those altered by Phlorizin (L17 and M35). These small and non-localized chemical shifts could be indicative of weak interaction and/or non-specific binding to the peptide by the two compounds. Both Phlorizin and R2, which show limited or no influence on amyloidogenesis, display potentially weak interactions with more C-terminal residues while the interaction of both Verbascoside and VPP with Aβ appear to be more centrally or N-terminally located. Due to the modest CSP values observed, these data may suggest a general preference for interaction rather than a conventional, structured binding site for all compounds examined. Our NMR studies, therefore, suggest a possible molecular mechanism responsible for their differing activities towards Aβ species in vitro (vide supra). Ligand association with the N-terminus (close to the metal binding site in Aβ) may be favorable in the development of multifunctional compounds to target metal-free and/or metal-associated Aβ species while interacting with the central hydrophobic residues of Aβ may also allow for general inhibition, as has been previously predicted4,6,9,10,15.

Ligand interaction with monomeric Aβ40 by 2D 1H/15N SOFAST-HMQC NMR (600 MHz).

Verbascoside (a) and VPP (b) were titrated into a solution of uniformly 15N-labeled Aβ40 (80 μM in 20 mM PO4, 50 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, 7% D2O (v/v), 10 °C). Blue color represents the spectrum obtained upon addition of 10 equiv of the ligand to Aβ40 (red color: the spectrum of Aβ40 only). All spectra were aligned at G29 due to non-uniform broadening of the water peak as a reference. Chemical shift perturbation (CSP) between the 0 and 10 equiv of all resolved residues was calculated and plotted as a function of the amino acid residue number in Aβ40 for (c) Verbascoside, (d) VPP, (e) Phlorizin and (f) R2. All CSP values are compared to the average (dashed line) and average + standard deviation (dotted line) for each titration. Values which exceed the average + standard deviation line are considered to be significant, suggesting potential interaction.

To gain further molecular level insight into the interactions between these polyphenols and different Aβ structures, saturation transfer difference (STD) NMR was employed to map the regions of both Verbascoside and VPP which bind to preformed Aβ42 fibrils (Fig. 6)18,28,49,50. The intensity of peaks within the STD spectra, relative to the reference spectra, is associated with the proximity of the ligand’s protons to the fibril50. From these values, a group epitope map can be generated, determining which protons of Verbascoside and VPP are in proximity to and binding with the fibrils. Verbascoside (Fig. 6c) only showed STD signals for protons linked to the glucose and rhamose rings. While most of these protons presented modest to weak signals in the STD spectrum, the protons on the C6 of the glucose ring indicated an extremely strong STD effect. For VPP, weak STD effect was observed around all methyl and ethyl protons of the esters appended to the sugar moieties. The stronger STD effect was observed around both the caffeic acid and hydroxytyrosol moieties, localized especially around the two aromatic protons of the catechol groups (Fig. 6d). This suggests that the esterification of the sugar rings of Verbascoside blocks the binding of the compound to the fibrils through the two sugar rings, redirecting their interaction to a different portion of the compound. It may be that the multiple hydroxyl groups of the sugars promote hydrogen bonds with some of the exposed side chains of the fibril; the esterification of the sugar rings could make these interactions sterically unfavorable and direct VPP to interact through hydrogen bonds and π–π interactions through the catechol moieties of the compound instead.

Ligand interaction with fibrillar Aβ42 by saturation transfer difference (STD) NMR (600 MHz).

STD NMR spectra of (a) Verbascoside and (b) VPP at a 250:1 ligand to peptide ratio using pre-assembled Aβ42 fibrils (1 μM). Comparison of the STD signal intensity (red) to the STD reference intensity (black) reflects the relative proximity of the corresponding proton to the Aβ42 fibril. The STD effect calculated from relative intensities was correlated to the structure of Verbascoside (c) and VPP (d) to generate group epitope maps.

The different binding modes identified by STD experiments led us to explore the affinity of these two compounds for fibrillar Aβ. Using a fluorescence blue shift assay, the change in the fluorescence emission wavelength was monitored as fibril was titrated into solution (Fig. S6a and b). Verbascoside and VPP were shown to have an affinity of 7.80 ± 0.75 μM and 6.98 ± 0.80 μM, respectively, under the condition employed in this study. Despite very different modes of binding to the fibril, the compounds have nearly identical affinities. It should be noted that the actual affinity for the fibril in solution is likely stronger than those measured; the concentration of fibrils was calculated based on the monomer equivalent concentration. It is not possible to measure the molar concentration of fibrils in solution given their heterogeneous length and subsequently heterogeneous molecular weight. The fibril concentration is likely much lower than the monomer equivalent which would affect the concentration values used in the fit. Because the exact fibril concentration cannot be measured, however and because the same sample of fibril was used for both titrations, we are confident that these results are internally consistent and suggest that the two compounds have very similar affinities.

The distinct difference in group epitope but similar affinity led us to investigate the binding site on the fibril for these two compounds; it was expected that two compounds with similar affinities but unique binding moieties would likely bind to separate regions of the fibril structure and therefore do not compete for binding. To probe this, we performed a competition titration experiment in which fibrils were first treated with 1 equiv of a compound (either Verbascoside or VPP) and then titrated with the other compound. The intensity of an STD peak associated with each compound (relative to the intensity of the same peak in the reference spectrum) was then used to monitor the binding of each compound to the fibril. As the competing compound is titrated into solution, if the compounds bind in the same site, it is expected that the relative intensity of the first compound’s peak will gradually decrease while the relative intensity of the titrant’s peak will increase as it competes the first compound off of the binding site. Conversely, under non-competitive binding conditions, the initial compound would maintain a constant relative intensity while the relative intensity of the titrant would increase as it binds at higher and higher concentrations. When Verbascoside was titrated into a solution already containing VPP and fibrils (Fig. S6c), it was observed that the relative intensity of the peak associated with Verbascoside increased during the titration while the relative intensity of the peak associated with VPP gradually decreased. This suggests that Verbascoside competes with VPP for a similar binding site on the fibril. The reverse of this experiment was performed (VPP titrated into a solution already containing Verbascoside and fibrils; Fig. S6d) and the same trend was observed. The relative intensity of the VPP peak increased while the relative intensity of the Verbascoside peak decreased slightly. This implies that, while the two compounds bind to the fibril using unique portions of their related structure, they are targeting a similar location on the fibril. Additionally, the blue shift assay suggests that they do so with a nearly identical affinity. This is unexpected and suggests that the esterification changes how the two compounds are able to disaggregate fibrillar species (vide supra) but they bind to the fibril in a relatively similar manner though using unique parts of their structure. It could be that the differing orientation of the sugar and catechol moieties of the two compounds is at least partly responsible for this difference in reactivity as STD group epitope maps reveal that the orientation is unique between compounds.

Antioxidant Properties

Because oxidative stress is believed to play a role in AD, it would be valuable for multifunctional probes to possess antioxidant activity, on top of the ability to interact simultaneously with Aβ species and various transition metal ions9,13,14. The ability of these six compounds to scavenge organic radical cations (i.e., ABTS•+) was determined by the Trolox equivalence antioxidant capacity (TEAC) assay using cell lysates (Fig. 7a)51,52. Both Verbascoside and Rutin, two known antioxidants31,32,52, scavenged ABTS•+ slightly better than Trolox (6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid) (by a factor of ca. 1.4 and 1.2, respectively). VPP, Phlorizin and F2 showed a lower ability to scavenge ABTS•+ relative to Trolox, suggesting limited function as antioxidants relative to the other compounds investigated herein. R2 presented no ability to scavenge ABTS•+. This, again, indicates that esterification of the sugar moiety transforms the function of the polyphenols. In this case, the antioxidant capacity of the all compounds was reduced upon esterification. Verbascoside’s activity was reduced by ca. 65% while Rutin lost all activity. The activity of Phlorizin was reduced by ca. 40%. This reduction in antioxidant capacity is surprising given the conservation of the catechol structures between Verbascoside/VPP and Rutin/R2 which are thought to be potentially responsible for ABTS•+ quenching through semi-quinone and quinone formation28,52.

Biological activities of Verbascoside (Verb), VPP, Rutin, R2, Phlorizin (Phlo) and F2.

(a) Free radical scavenging activity of Verbascoside, VPP, Rutin, R2, Phlorizin and F2 evaluated by a cell lysate-based TEAC assay. The TEAC values are relative to a vitamin E analogue, Trolox (6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid). (b) Influence of Verbascoside, VPP and Rutin on cytotoxicity induced by metal-free Aβ and metal-Aβ species in N2a cells. Cells treated with Aβ40 or Aβ42 (20 μM), a metal chloride salt (CuCl2 or ZnCl2; 20 μM) and a compound [Verbascoside, VPP and Rutin (20 μM)] were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. Cell viability was determined by the MTT assay. Values of cell viability (%) were calculated compared to that of cells treated with DMSO only (0–1%, v/v). Error bars represent the standard errors from three independent experiments.

Regulating Cytotoxicity Related to Metal-Free and Metal-Associated Aβ

Previous studies of Verbascoside and Rutin have suggested the two compounds may alleviate the toxicity of Aβ species in SH-SY5Y and APPswe cells, respectively22,24. We probed this relationship further to examine the effect of these two compounds, as well as VPP, on the cytotoxicity of both metal-free Aβ and metal–Aβ in murine Neuro-2a neuroblastoma (N2a) cells. In the absence of Aβ, Verbascoside was relatively nontoxic with and without metal ions (Fig. S7). VPP, however, reduced cell viability (ca. 70%) at high concentrations in the presence of either Cu(II) or Zn(II), but showed minimal toxicity in the absence of metal ions. Rutin had no significant impact on cell viability under any conditions (Fig. S6).

Cells incubated with Aβ (20 μM) in either the absence or presence of metal ions (Cu(II) or Zn(II), 20 μM) indicated viability of ca. 70–80% under all conditions (Fig. 7b). The addition of Verbascoside (20 μM) improved cell survival (ca. 90–100%) regardless of both Aβ isoforms and the presence or absence of metal ions. VPP (20 μM), however, was generally unable to regulate Aβ-triggered cytotoxicity. Finally, treatment of cells with Rutin (20 μM) yielded slight improvements in cell survival under all conditions. Overall, Verbascoside was capable of attenuating the broad toxicity indicated in the presence of both metal-free Aβ and metal–Aβ. Furthermore, esterification of the compound is shown to limit these protective capabilities.

Discussion

Naturally occurring polyphenolic glycosides (Phlorizin, Verbascoside and Rutin), along with their esterified derivatives (F2, VPP and R2), were investigated for their potential to modulate the aggregation and toxicity of metal-free Aβ and metal–Aβ. Both Verbascoside and VPP, bearing multiple catechol moieties, were capable of distinctly redirecting the aggregation of metal-free Aβ (mainly, VPP) and/or metal–Aβ to different extents, as confirmed by both biochemical and TEM studies. The ability of these two compounds to interact with both metal ions and Aβ was confirmed through physical methods, including UV-Vis and 1D/2D/STD NMR. Verbascoside and VPP are able to interact with both Cu(II) and Zn(II) as well as with multiple forms of Aβ. The esterification of Verbascoside to VPP distinctly alters the interactions between the compounds and the components of the metal–Aβ system studied herein, suggesting that the properties (metal binding and Aβ interaction) can be tunable by synthetic modifications. In addition, Verbascoside is shown to have some promising chemical properties for a potential probe (antioxidant capacity, no toxicity and cytoprotective against both metal-free Aβ and metal–Aβ). Overall, this study points to Verbascoside as a promising starting point for constructing a new multifunctional probe to interrogate the etiology of AD.

This study also lends insight into the efficacy of unique chemical moieties in design of anti-amyloidogenic compounds. Comparing Phlorizin, Verbascoside and Rutin to each other, there is a direct correlation between the number of catechol moieties and the efficacy of each compound against metal-free Aβ and metal-Aβ aggregation. This is further supported by the group epitope map generated from STD NMR for VPP which shows strong STD effect around both catechols. This suggests that the catechol moiety specifically, not just polyphenols as a general class of compounds, may be effective at redirecting the protein misfolding. Previous studies have also indicated that including a catechol-like moiety makes a small molecule more effective;28 two of the most thoroughly investigated anti-amyloidogenic natural products, EGCG and curcumin, contain multiple variations of the catechol moiety (pyrogallol for EGCG, o-methyl-catechol for curcumin), further indicating that the catechol moiety is an effective component of an anti-amyloidogenic probe20,53. It should be noted, however, that catechol-containing compounds have been shown to be promiscuous in their action and functionality so their use and functionalization must be carefully considered in compound design for in vivo applications in order to avoid off-target effects54,55.

We have also highlighted the importance of carefully chosen synthetic alterations to efficacious reagents. In this suite of compounds, it is apparent that esterification of the sugar moieties affected the efficacy of the compounds in the various assays to differing extents; esterification increased the ability of VPP to alter the structure of metal-free Aβ aggregates while simultaneously maintaining its affinity for preformed fibrils relative to that of Verbascoside, its parent compound. Esterification also reduced the ability of all compounds to scavenge organic radicals despite not directly modifying the catechol moiety thought to be responsible for the scavenging activity. Overall, this points to the unpredictability inherent in small molecule design for complex biological systems; with many variables all contributing to the disease phenotype, it is challenging, if not impossible, to accurately predict the effects of small structural changes on a compounds efficacy against the suite of potential targets. Thus, the performance of the compounds evaluated here may serve as a benchmark for which compounds are most worthwhile investigating further in more complex and biologically relevant systems. Furthermore, it indicates the care which must be taken when functionalizing known compounds. Even potentially reversible changes, such as esterification, may drastically alter the compound’s function, in both beneficial and detrimental ways. Importantly, however, it appears from the data presented herein that Verbascoside possesses positive characteristics for a compound in the investigation of the role of Aβ in AD and, furthermore, is structurally amenable to a variety of future derivatization aimed at further improving its function.

Methods

Materials and Procedures

All reagents were purchased from commercial suppliers and used as received unless otherwise noted. The natural products (Phlorizin, Verbascoside and Rutin) and their previously synthesized, esterified derivatives (F2, VPP and R2) were prepared following the previously reported methods30,31,32. Aβ40 and Aβ42 were purchased from Anaspec (Fremont, CA, USA). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were recorded on a Philips CM-100 transmission electron microscope (Microscopy and Image Analysis Laboratory, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Optical spectra for metal binding were recorded on an Agilent 8453 UV–Visible (UV–Vis) spectrophotometer. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra for the characterization of Zn(II) binding studies of Verbascoside and VPP were acquired on an Agilent 400 MHz NMR spectrometer. NMR studies of 15N-labeled Aβ40 with ligands were carried out on a Bruker 600 MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with a cryogenic probe. Absorbance values for biological assays, including the TEAC assay and cell viability assay, were measured on a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Amyloid-β (Aβ) Inhibition and Disaggregation Experiments

Aβ experiments were performed according to previously published methods28,39. Prior to the sample preparation, Aβ40 or Aβ42 was dissolved with ammonium hydroxide (NH4OH, 1% v/v, aq), aliquoted, lyophilized and stored at −80 °C. Stock solutions (ca. 200 μM) of Aβ40 and Aβ42 were prepared by dissolving the lyophilized peptide in 1% NH4OH (10 μL) and diluting with doubly distilled (dd) H2O. The peptide stock solution was diluted to a final concentration of 25 μM in buffered solution containing HEPES [4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid; 20 μM, pH 6.6 for Cu(II) samples; pH 7.4 for metal-free and Zn(II) samples] and NaCl (150 μM). For the inhibition studies28,39, compound (50 μM final concentration, 1% v/v DMSO) was added to the sample of Aβ40 or Aβ42 in the absence and presence of a metal chloride salt (CuCl2 or ZnCl2, 25 μM) followed by incubation for 4 and 24 h at 37 °C with constant agitation. For the disaggregation studies28,39, Aβ40 or Aβ42 with and without metal ions was first incubated for 24 h at 37 °C with continuous agitation prior to the addition of compound (50 μM). The resulting samples were incubated for an additional 4 or 24 h at 37 °C with constant agitation.

Gel Electrophoresis with Western Blotting

The samples from the inhibition and disaggregation experiments were analyzed by gel electrophoresis with Western blot using an anti-Aβ antibody (6E10)20,28. Each sample (10 μL) was separated on a 10–20% Tris-tricine gel (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA). Following separation, the gel was transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane which was blocked with bovine serum albumin (BSA, 3% w/v, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T) for 3 h at room temperature. The membrane was treated with antibody (6E10, Covance, Princeton, NJ, USA; 1:2000) in a solution of BSA (2% w/v) in TBS-T overnight at 4 °C. Following washing, the membrane was treated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat antimouse secondary antibody (1:5000; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) in 2% BSA in TBS-T solution for 1 h at room temperature. Protein bands were visualized using ThermoScientific Supersignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA).

Transmission Electron Microscopy

The samples for TEM were prepared following a previously reported method28,39. Glow-discharged grids (Formar/Carbon 300-mesh, Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA) were treated with the samples from the disaggregation experiments (5 μL, 25 μM Aβ) for 2 min at room temperature. Excess sample was removed with filter paper and washed with ddH2O. Each grid was stained with uranyl acetate (1% w/v, ddH2O, 5 μL, 1 min), blotted to remove excess stain and dried for 15 min at room temperature. TEM images were taken by a Philips CM-100 transmission electron microscope (80 kV, 25,000× magnification).

Metal Binding Studies

The interaction of Phlorizin, F2, Verbascoside, VPP, Rutin and R2 with Cu(II) and Zn(II) was determined by UV-Vis or 1H NMR, respectively, based on previously reported procedures20,56. A solution of ligand (20 μM, pH 7.4) was prepared, treated with 0.5 to 10 equiv of CuCl2 and incubated at room temperature for 2 h (for Phlorizin, F2, Verbascoside, VPP, Rutin and R2). The optical spectra of the resulting solutions were measured by UV-Vis. The interaction of both Verbascoside and VPP with ZnCl2 was observed by 1H NMR (500 MHz). ZnCl2 was titrated into a solution of Verbascoside or VPP (2 mM) in DMSO-d6 and the spectra were recorded.

2D NMR Spectroscopy

The interaction of Aβ40 with Phlorizin, Verbascoside, VPP and R2 was monitored by 2D band-Selective Optimized Flip-Angle Short Transient Heteronuclear Multiple Quantum Coherence (SOFAST-HMQC) at 8 °C48. Uniformly-15N-labeled Aβ40 (rPeptide, Bogart, GA, USA) was first dissolved in 1% NH4OH and lyophilized. The peptide was re-dissolved in 3 μL of DMSO-d6 (Cambridge Isotope, Tewksbury, MA, USA) and diluted with phosphate buffer, NaCl, D2O and ddH2O to a final peptide concentration of 80 μM (20 mM PO4, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 7% v/v D2O). Each spectrum was obtained using 64 complex t1 points and a 0.1 sec recycle delay on a Bruker Avance 600 MHz spectrometer. The 2D data were processed using TOPSPIN 2.1 (from Bruker). Resonance assignment was performed with SPARKY 3.1134 using published assignments for Aβ40 as a guide57,58,59. Chemical shift perturbation (CSP) was calculated using the following equation (Eq. 1):

Saturation Transfer Difference (STD) NMR Spectroscopy

For the STD NMR48 experiments, an 150 μM solution of fibrillar Aβ42 was prepared by incubating Aβ42 for 24 h at 37 °C with constant agitation in 10 mM deuterated Tris–DCl, 95% D2O at pD 7.4 (corrected for the isotope effect). The samples for STD experiments were prepared by diluting fiber to 1 μM (effective monomer concentration) into 10 mM deuterated Tris–DCl to which was added 250 μM of ligand (0.5% DMSO-d6). STD experiments were acquired with a train of 50 dB Gausian-shaped pulses of 0.049 sec with an interval of 0.001 sec at either −1.0 ppm (on resonance) or 40 ppm (off resonance) with a total saturation time of 2 sec on a Bruker 600 MHz NMR spectrometer. A total of 1024 scans were recorded for the STD spectrum and 512 scans were recorded for the reference spectrum at 25 °C. An inter-scan delay of 1 sec was used for both the STD and the reference experiments.

For the competition experiments with Verbascoside and VPP, the above procedure was followed for sample preparation. STD experiments were acquired with a train of 50 dB Gausian-shaped pulses of 0.049 sec with an interval of 0.001 sec at either −1.0 ppm (on resonance) or 40 ppm (off resonance) with a total saturation time of 2 sec on a Bruker 500 MHz NMR spectrometer. A total of 2048 scans were recorded for the STD spectrum and 1024 scans were recorded for the reference spectrum at 25 °C. An inter-scan delay of 1 sec was used for both the STD and the reference experiments. To a solution already containing either Verbascoside or VPP (250 μM), the other compound was titrated to 0.5 equiv (125 μM), 1 equiv (250 μM) and 3 equiv (750 μM). The intensity of peaks unique to Verbascoside (3.85 ppm) and VPP (7.78 ppm) in the STD spectra relative to their intensity in the reference spectra were used to monitor the binding of the compounds to the fiber.

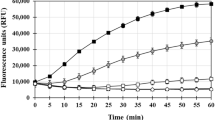

Blue Shift Fluorescence Assay

The change in the fluorescence emission wavelength of Verbascoside or VPP was monitored upon treatment with Aβ42 fibrils on a Fluoromax-4 Spectrofluorimeter (Horiba Scientific, Edison, NJ, USA). A 25 μM solution of either Verbascoside or VPP in buffer (20 mM PO4, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl) was titrated with preformed Aβ42 fibrils, prepared as described above for STD experiments. The fluorescence emission was monitored between 380 and 550 nm following excitation (350 nm for Verbascoside and 330 nm for VPP) with slits setting for 5 nm bandwidths. The blue shift was calculated by the difference between the emission maximum wavelength of the titration point and the emission maximum wavelength of the compound in absence of fibrils. The data was then fit to a hyperbolic curve to calculate the Kd value.

Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity (TEAC) Assay

The antioxidant activity of Phlorizin, F2, Verbascoside, VPP, Rutin and R2 was determined by the TEAC assay employing cell lysate following the protocol of the antioxidant assay kit purchased from Cayman Chemical Company (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) with modifications18. Murine Neuro-2a (N2a) cells were used for this assay. This cell line, purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA), was maintained in media containing 50% Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) and 50% OPTI-MEM (GIBCO), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Sigma), 1% Non-essential Amino Acids (NEAA, GIBCO), 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin (GIBCO). The cells were grown and maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. For the antioxidant assay using cell lysates, cells were seeded in a 6 well plate and grown to approximately 80–90% confluence. Cell lysates were prepared following the previously reported method with modifications60. N2a cells were washed once with cold PBS (pH 7.4, GIBCO) and harvested by gently pipetting off adherent cells with cold PBS. The cell pellet was generated by centrifugation (2,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C). This cell pellet was sonicated on ice (5 sec pulses, 5 times with 20 sec intervals between each pulse) in 2 mL of cold Assay Buffer (5 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, containing 0.9% NaCl and 0.1% glucose). The cell lysates were centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was removed and stored on ice until use. To standard and sample wells in a 96 well plate, cell lysates (10 μL) were delivered; they were followed by addition of compound, metmyoglobin, ABTS and H2O2 in order. After 5 min incubation at room temperature on a shaker, absorbance values at 750 nm were recorded. The final concentrations (0.045, 0.090, 0.135, 0.180, 0.225 and 0.330 mM) of Trolox (Sigma-Aldrich; dissolved in DMSO) and all polyphenolic glycosides were used. The percent inhibition was calculated according to the measured absorbance [% Inhibition = (A0-A)/A0, where A0 is absorbance of the supernatant of cell lysates] and was plotted as a function of compound concentration. The TEAC value of ligands was calculated as a ratio of the slope of the standard curve of the compound to that of Trolox.

Cell Viability Measurements

Cell viability upon treatment with compounds was determined using the MTT assay (Sigma). N2a cells were seeded in a 96 well plate (15,000 cells in 100 μL per well). The cells were treated with Aβ (20 μM) with or without either CuCl2 or ZnCl2 (20 μM), followed by the addition of compound (20 μM, 1% v/v final DMSO concentration for Verbascoside, VPP and Rutin) and incubated for 24 h in the cells. After incubation, 25 μL MTT [5 mg/mL in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, GIBCO, Grand Island, NY, USA] was added to each well and the plate was incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. Formazan produced by the cells was solubilized using an acidic solution of N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, 50% v/v, aq) and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS, 20% w/v) overnight at room temperature in the dark. The absorbance was measured at 600 nm using a microplate reader. Cell viability was calculated relative to cells treated an equivalent volume of DMSO.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Korshavn, K. J. et al. Reactivity of Metal-Free and Metal-Associated Amyloid-β with Glycosylated Polyphenols and Their Esterified Derivatives. Sci. Rep. 5, 17842; doi: 10.1038/srep17842 (2015).

References

Jakob-Roetne, R. & Jacobsen, H. Alzheimer’s disease: from pathology to therapeutic approaches. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 48, 3030–3059 (2009).

Franco, R. & Cedazo-Minguez, A. Successful therapies for Alzheimer’s disease: why so many in animal models and none in humans? Front. Pharmacol. 5, 146 (2014).

Gouras, G. K., Olsson, T. T. & Hansson, O. Beta-amyloid peptides and amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurotherapeutics 12, 3–11 (2014).

Savelieff, M. G., Lee, S., Liu, Y. & Lim, M. H. Untangling amyloid-beta, tau and metals in Alzheimer’s disease. ACS Chem. Biol. 8, 856–865 (2013).

Rauk, A. The chemistry of Alzheimer’s disease. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 2698–2715 (2009).

Hamley, I. W. The amyloid beta peptide: a chemist’s perspective. Role in Alzheimer’s and fibrillization. Chem. Rev. 112, 5147–5192 (2012).

Benilova, I., Karran, E. & De Strooper, B. The toxic Aβ oligomer and Alzheimer’s disease: an emperor in need of clothes. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 349–357 (2012).

Lovell, M. A., Robertson, J. D., Teesdale, W. J., Campbell, J. L. & Markesbery, W. R. Copper, iron and zinc in Alzheimer’s disease senile plaques. J. Neurol. Sci. 158, 47–52 (1998).

Kepp, K. P. Bioinorganic chemistry of Alzheimer’s disease. Chem. Rev. 112, 5193–5239 (2012).

Faller, P., Hureau, C. & Berthoumieu, O. Role of metal ions in the self-assembly of the Alzheimer’s amyloid-beta peptide. Inorg. Chem. 52, 12193–12206 (2013).

Bush, A. I. The metal theory of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 33, S277–281 (2013).

Parthasarathy, S., Yoo, B., McElheny, D., Tay, W. & Ishii, Y. Capturing a reactive state of amyloid aggregates: NMR-based characterization of copper-bound Alzheimer disease amyloid beta-fibrils in a redox cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 9998–10010 (2014).

Faller, P. & Hureau, C. A bioinorganic view of Alzheimer’s disease: when misplaced metal ions (re)direct the electrons to the wrong target. Chemistry 18, 15910–15920 (2012).

Eskici, G. & Axelsen, P. H. Copper and oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochemistry 51, 6289–6311 (2012).

Savelieff, M. G., DeToma, A. S., Derrick, J. S. & Lim, M. H. The ongoing search for small molecules to study metal-associated amyloid-beta species in Alzheimer’s disease. Acc. Chem. Res. 47, 2475–2482 (2014).

Beck, M. W., Pithadia, A. S., DeToma, A. S., Korshavn, K. J. & Lim, M. H. Ligand design to target and modulate metal-protein interactions in neurodegenerative diseases in Ligand Design in Medicinal Inorganic Chemistry (ed. Storr, T. ) Ch. 10, 257–286 (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2014).

Beck, M. W. et al. A rationally designed small molecule for identifying an in vivo link between metal–amyloid-β complexes and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Chem. Sci. 6, 1879–1886 (2015).

Lee, S. et al. Rational design of a structural framework with potential use to develop chemical reagents that target and modulate multiple facets of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 299–310 (2014).

Porat, Y., Abramowitz, A. & Gazit, E. Inhibition of amyloid fibril formation by polyphenols: structural similarity and aromatic interactions as a common inhibition mechanism. Chem. Biol. Drug. Des. 67, 27–37 (2006).

Hyung, S. J. et al. Insights into antiamyloidogenic properties of the green tea extract (–)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate toward metal-associated amyloid-beta species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 3743–3748 (2013).

Kurisu, M. et al. Inhibition of amyloid beta aggregation by acteoside, a phenylethanoid glycoside. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 77, 1329–1332 (2013).

Wang, H. et al. Acteoside protects human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells against beta-amyloid-induced cell injury. Brain. Res. 1283, 139–147 (2009).

Wang, S. W. et al. Rutin inhibits beta-amyloid aggregation and cytotoxicity, attenuates oxidative stress and decreases the production of nitric oxide and proinflammatory cytokines. Neurotoxicology 33, 482–490 (2012).

Jimenez-Aliaga, K., Bermejo-Bescos, P., Benedi, J. & Martin-Aragon, S. Quercetin and rutin exhibit antiamyloidogenic and fibril-disaggregating effects in vitro and potent antioxidant activity in APPswe cells. Life Sci. 89, 939–945 (2011).

Hertel, C. et al. Inhibition of the electrostatic interaction between beta-amyloid peptide and membranes prevents beta-amyloid-induced toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 9412–9416 (1997).

Schweigert, N., Zehnder, A. J. & Eggen, R. I. Chemical properties of catechols and their molecular modes of toxic action in cells, from microorganisms to mammals. Environ. Microbiol. 3, 81–91 (2001).

Severino, J. F., Goodman, B. A., Reichenauer, T. G. & Pirker, K. F. Is there a redox reaction between Cu(II) and gallic acid? Free Radic. Res. 45, 115–124 (2011).

DeToma, A. S. et al. Synthetic flavonoids, aminoisoflavones: interaction and reactivity with metal-free and metal-associated amyloid-beta species. Chem. Sci. 5, 4851–4862 (2014).

Milko, P. et al. The phenoxy/phenol/copper cation: a minimalistic model of bonding relations in active centers of mononuclear copper enzymes. Chemistry 14, 4318–4327 (2008).

Baldisserotto, A. et al. Synthesis, antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of a new phloridzin derivative for dermo-cosmetic applications. Molecules 17, 13275–13289 (2012).

Vertuani, S. et al. Activity and stability studies of verbascoside, a novel antioxidant, in dermo-cosmetic and pharmaceutical topical formulations. Molecules 16, 7068–7080 (2011).

Baldisserotto, A. et al. Design, synthesis and biological activity of a novel Rutin analogue with improved lipid soluble properties. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 23, 264–271 (2015).

Lampronti, I., Borgatti, M., Vertuani, S., Manfredini, S. & Gambari, R. Modulation of the expression of the proinflammatory IL-8 gene in cystic fibrosis cells by extracts deriving from olive mill waste water. Evid. Based. Complement. Alternat. Med. 2013, 960603 (2013).

Egleton, R. D. & Davis, T. P. Development of neuropeptide drugs that cross the blood-brain barrier. NeuroRx 2, 44–53 (2005).

Egleton, R. D. et al. Improved blood-brain barrier penetration and enhanced analgesia of an opioid peptide by glycosylation. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 299, 967–972 (2001).

Yagi-Utsumi, M., Kameda, T., Yamaguchi, Y. & Kato, K. NMR characterization of the interactions between lyso-GM1 aqueous micelles and amyloid beta. FEBS Lett. 584, 831–836 (2010).

McLaurin, J., Golomb, R., Jurewicz, A., Antel, J. P. & Fraser, P. E. Inositol stereoisomers stabilize an oligomeric aggregate of Alzheimer amyloid beta peptide and inhibit abeta -induced toxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 18495–18502 (2000)

Rautio, J. et al. Prodrugs: design and clinical applications. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 255–70

Hindo, S. S. et al. Small molecule modulators of copper-induced Abeta aggregation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 16663–16665 (2009).

DeToma, A. S., Choi, J. S., Braymer, J. J. & Lim, M. H. Myricetin: a naturally occurring regulator of metal-induced amyloid-beta aggregation and neurotoxicity. Chem Bio Chem 12, 1198–1201 (2011).

Hider, R. C., Liu, Z. D. & Khodr, H. H. Metal chelation of polyphenols. Methods Enzymol. 335, 190–203 (2001).

Satterfield, M. & Brodbelt, J. S. Enhanced detection of flavonoids by metal complexation and electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 72, 5898–5906 (2000).

Mmatli, E. E. et al. Identification of major metal complexing compounds in Blepharis aspera. Anal. Chim. Acta. 597, 24–31 (2007).

Afanas’ev, I. B., Ostrakhovitch, E. A., Mikhal’chik, E. V., Ibragimova, G. A. & Korkina, L. G. Enhancement of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of bioflavonoid rutin by complexation with transition metals. Biochem. Pharmacol. 61, 677–684 (2001).

Brown, J. E., Khodr, H., Hider, R. C. & Rice-Evans, C. A. Structural dependence of flavonoid interactions with Cu2+ ions: implications for their antioxidant properties. Biochem. J. 330, 1173–1178 (1998).

Sever, M. J. & Wilker, J. J. Visible absorption spectra of metal-catecholate and metal-tironate complexes. Dalton Trans. 7, 1061–1072 (2004).

Seidel, V. et al. Phenylpropanoids from Ballota nigra L. inhibit in vitro LDL peroxidation. Phytother. Res. 14, 93–98 (2000).

Schanda, P. & Brutscher, B. Very fast two-dimensional NMR spectroscopy for real-time investigation of dynamic events in proteins on the time scale of seconds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 8014–8015 (2005).

Mayer, M. & Meyer, B. Group epitope mapping by saturation transfer difference NMR to identify segments of a ligand in direct contact with a protein receptor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 6108–6117 (2001).

Meyer, B. & Peters, T. NMR spectroscopy techniques for screening and identifying ligand binding to protein receptors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 42, 864–890 (2003).

Re, R. et al. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 26, 1231–1237 (1999).

Rice-Evans, C. A., Miller, N. J. & Paganga, G. Structure-antioxidant activity relationships of flavonoids and phenolic acids. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 20, 933–956 (1996).

Yang, F. et al. Curcumin inhibits formation of amyloid beta oligomers and fibrils, binds plaques and reduces amyloid in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 5892–5901 (2005).

Priyadarsini, K. I. Chemical and structural features influencing the biological activity of curcumin. Curr. Pharm. Des. 19, 2093–2100 (2013).

Ingolfsson, H. I. et al. Phytochemicals perturb membranes and promiscuously alter protein function. ACS Chem. Biol. 9, 1788–1798 (2014).

Pithadia, A. S. et al. Reactivity of diphenylpropynone derivatives toward metal-associated amyloid-beta species. Inorg. Chem. 51, 12959–12967 (2012).

Vivekanandan, S., Brender, J. R., Lee, S. Y. & Ramamoorthy, A. A partially folded structure of amyloid-beta(1-40) in an aqueous environment. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 411, 312–316 (2011).

Yoo, S. I. et al. Inhibition of amyloid peptide fibrillation by inorganic nanoparticles: functional similarities with proteins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 50, 5110–5115 (2011).

Fawzi, N. L., Ying, J., Torchia, D. A. & Clore, G. M. Kinetics of amyloid beta monomer-to-oligomer exchange by NMR relaxation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 9948–9951 (2010).

Spencer, V. A., Sun, J. M., Li, L. & Davie, J. R. Chromatin immunoprecipitation: a tool for studying histone acetylation and transcription factor binding. Methods 31, 67–75 (2003).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) Grant funded by the Korean Government [NRF-2014S1A2A2028270 to M.H.L. and A.R.; (MSIP) NRF-2014R1A2A2A01004877 to M.H.L.]; the 2015 Research Fund (Project Number 1.140101.01) of Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology (UNIST) and the DGIST R&D Program of the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning of Korea (15-BD-0403) (to M.H.L.); the University of Michigan Protein Folding Disease Initiative (to A.R. and M.H.L.); Ministry of Education and Research of Italy (PRIN, Grant 20105YY2HL_006) (to S.M.); the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) and the Center for Women In Science, Engineering and Technology (WISET) Grant funded by the Korean Government [Program for Returners into R&D by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (MSIP)] (KW-2014-PPD-0067) (to Y.J.K.). The authors thank Dr. Russell Senthamarai for help with 2D NMR experiments, as well as Dr. Vivekanandan for assistance with the NMR spectrometer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.H.L., S.M. and A.R. directed the overall research. S.V. prepared the compounds. K.J.K., M.J. and Y.J.K. performed the gel/Western blot analyses. A.K. performed TEM studies. K.J.K. and A.B. conducted 2D and STD NMR studies. M.J. and K.J.K. carried out metal binding investigations. M.J. performed the TEAC assay and toxicity studies in living cells. K.J.K. and M.H.L. wrote the manuscript with collaboration with S.V., S.M. and A.R. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Korshavn, K., Jang, M., Kwak, Y. et al. Reactivity of Metal-Free and Metal-Associated Amyloid-β with Glycosylated Polyphenols and Their Esterified Derivatives. Sci Rep 5, 17842 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep17842

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep17842

This article is cited by

-

Alleviating the unwanted effects of oxidative stress on Aβ clearance: a review of related concepts and strategies for the development of computational modelling

Translational Neurodegeneration (2023)

-

Voltammetric investigation of the complexing effect of Capparis spinosa on heavy metals: Application in the treatment of water

Ionics (2023)

-

The nickel-chelator dimethylglyoxime inhibits human amyloid beta peptide in vitro aggregation

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Interaction of Amyloid Aβ(9–16) Peptide Fragment with Metal Ions: CD, FT-IR, and Fluorescence Spectroscopic Studies

International Journal of Peptide Research and Therapeutics (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.