Abstract

Anisotropic metamaterials with hyperbolic dispersion can be used to design waveguides with unusual properties. We show that, in contrast to planar waveguides, geometric confinement leads to coupling of ordinary (forward) and extraordinary (backward) modes and formation of hybrid waveguided modes, which near the crossing point may exhibit slow, stopped or superluminal behavior accompanied by very strong group velocity dispersion. These modes can be used for designing stopped-light nanolasers for nanophotonic applications and dispersion-facilitated signal reshaping in telecom applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metamaterials are media with optical properties dependent on the architecture of their subwavelength-structure. Their geometry and, thus, optical properties can be tuned to enable unusual optical phenomena such as negative refraction, cloaking and many others1. Among various metamaterial designs, uniaxial anisotropic metamaterials with an elliptic or hyperbolic dispersion of the electromagnetic waves attract especial interest due to their simple realization and advantageous optical properties for sensing, nonlinear optical applications and spontaneous emission control2,3,4,5. These metamaterials can be described within an effective medium description by a diagonal permittivity tensor with components εxx = εyy and εzz. This description is accurate if the size and distance between the nanostructures forming the metamaterial is much smaller than the wavelength and if the values of the effective permittivity components are not vanishing, where nonlocal effects occur6. Such metamaterials support two types of propagating waves, called ordinary and extraordinary waves. Ordinary waves have an electric field normal to the z axis. Therefore, for these waves the metamaterial has an effective permittivity εxx with a typical spheroid isofrequency surfaces. Extraordinary waves have a component of the electric field along the anisotropy axis (z-axis) and, therefore, they can have either a conventional elliptic dispersion for frequencies where both εxx and εzz have the same sign or a hyperbolic dispersion in the frequency range where εxx and εzz have opposite signs5. Such anisotropic metamaterials can be realized as plasmonic-dielectric multilayers with hyperbolic regime occurring for εxx = εyy < 0 and εzz > 0 or plasmonic nanorod arrays in a dielectric matrix with hyperbolic dispersion condition εxx = εyy > 0 and εzz < 0.

Such anisotropic metamaterials have recently been proposed to realise deep-subwavelength planar waveguides utilizing their peculiar hyperbolic dispersion7,8,9, providing a unique opportunity to guide bulk plasmon polaritons in the metamaterial slab7. These metamaterial-based waveguides exhibit unusual properties particularly in the case of hyperbolic dispersion where the propagating modes can be left-handed (backward waves) and highly confined8,9,10,11. While planar hyperbolic metamaterial waveguides (MWs) preserve the nature of ordinary and extraordinary modes of the infinite anisotropic metamaterial, in three-dimensional waveguides, mode confinement in 2 dimensions (2D) significantly modifies the behavior of waveguided modes of different polarizations.

In this paper, we analyze the properties of waveguided modes supported by anisotropic metamaterial waveguides with 2D confinement in both elliptic and hyperbolic regimes. It will be shown that although in some particular cases (e.g., planar waveguides) modes can be divided into extraordinary and ordinary modes5,7, in general, for arbitrary boundary conditions, eigenmodes have a mixed nature leading to hybrid modes (HMs) having properties of both extraordinary and ordinary modes. Due to the different nature of the interacting modes (conventional ordinary and backward extraordinary), hybrid modes exhibit unusual optical properties, such as anomalous dispersion leading to superluminal and stopped light, which can be used in the development of new integrated photonic devices and active metamaterial functionalities.

We consider a waveguide made of an anisotropic hyperbolic metamaterial with confinement in the direction of the extraordinary z-axis and one of the ordinary x-axis, so that modes are guided along the ordinary y-axis. In the complementary case, the confinement may be imposed in the ordinary x- and y- directions with guiding occurring along the extraordinary z-axis. The effective permittivity tensor of the metamaterial is considered the same as in the case of an infinite metamaterial: εxx = εyy > 0 and εzz < 0, corresponding to the metamaterial realization as an array of nanorods aligned along z-direction (Fig. 1(a)).

(a) Schematic of an anisotropic metamaterial waveguide. (b) (from left to right) The simulated intensity distributions for (1, 1) ordinary, (1, 4) extraordinary and hybrid modes. (1, 1) and (1, 4) modes are calculated using PEC boundary conditions, while the HM mode is calculated for a realistic MW in air. (c) Isofrequency surfaces for the elliptic regime (εxx = 9 and εzz = 20): (blue) ordinary and (green) extraordinary modes and (red) extraordinary hyperbolic modes (εxx = 9 and εzz = −20). (d) Mode dispersions from (c). The colors of the lines in (d) corresponds to the isofrequency surfaces in (c) for each case.

Before presenting numerical simulations of the waveguide properties, we first consider an intuitive model of an anisotropic waveguide. The coupled wave equations governing the behavior of propagating modes E(x, y, z) = E(x, z)exp(iβy) within the waveguide can be written as12

where β is the propagation constant of a given mode, k0 = 2π/λ0 and λ0 is the wavelength of light in vacuum, with

where Eqs (2) and (3) correspond to the ordinary and extraordinary waves, respectively and W describes a coupling between modes, which takes into account boundary effects and shape and dimensions of the waveguide.

In both the planar waveguides and rectangular waveguides with perfect electric conductor (PEC) boundary conditions13,14 or with planar metamaterial waveguides7,8,9, W = 0. Consequently, modes with polarization along ordinary and extraordinary directions are decoupled (Fig. 1(b), first two mode profiles) and the values for the propagation constant for ordinary (βo) and extraordinary (βe) modes in Eq. (1) can be determined from

where knx = nπ/a and kmz = mπ/b with (n, m) and (n’, m’) are the integers corresponding to the mode order of the ordinary and extraordinary modes, respectively and a and b are the height and width of the rectangular metamaterial waveguide, respectively (Fig. 1(b)). Thus, when admitting the PEC boundary conditions, ordinary waveguided modes βo can be decomposed choosing a basis of ordinary plane-waves, while extraordinary modes βe choosing an extraordinary plane-wave basis.

In order to analyze the mode structure in different dispersion regimes, we considered the anisotropic permittivity tensor components εxx = 9 and εzz = 20 for the elliptic dispersion and εzz = −20 for the hyperbolic dispersion. These values are typical for hyperbolic metamaterials based on plasmonic nanorod arrays15. Figure 1(c) shows the cross-section at a given kx of the isofrequency surfaces mapped by Eqs (5,6) in k-space (kx, β, kz) for both ordinary and extraordinary directions. For extraordinary modes in the elliptic regime (εzz > 0 and εxx > 0), this surface is an ellipsoid, while in the hyperbolic regime (εzz < 0 and εxx > 0), it represents a hyperboloid. Figure 1(d) shows the dispersion of ordinary and extraordinary waveguided modes in both elliptical and hyperbolic cases. While a similar behavior is observed for the ordinary (blue curve) and extraordinary elliptic (green) mode, the extraordinary hyperbolic (red) mode has a completely different behavior. In the hyperbolic case, the mode dispersion has a negative slope and, thus its group velocity is negative. Therefore, extraordinary hyperbolic modes are backward modes5,16. Ordinary and hyperbolic modes can, thus, be degenerated at frequency ωd at which the propagation constants of both extraordinary and ordinary modes (in this case, the (1, 1) ordinary mode with the (1, 4) hyperbolic mode) are equal. As one can see from Eqs (5,6), the value of ωd can be designed at will by changing waveguide dimensions (a, b) and metamaterial properties (εxx, εzz). For example, to achieve the degenerated modes at the telecom wavelength of λd = 1.55 μm, the dimensions of the waveguide should be b = 80 nm and a = 300 nm for the metamaterial parameters discussed here.

In a realistic waveguide geometry (no PEC boundary conditions), the coupling W is generally different from zero. Defining the eigenvalue equations  ,

,  and

and  , where γ and αeo are the anisotropic coupling constant and the coupling constant between extraordinary and ordinary modes, respectively. The latter coupling arises from the geometrical confinement of fields in the waveguide and have magnitude governed by modal overlap between ordinary and extraordinary modes resulting from scattering at the edges of the waveguide. In this framework, the mode propagation constants in Eq. (1) take the form

, where γ and αeo are the anisotropic coupling constant and the coupling constant between extraordinary and ordinary modes, respectively. The latter coupling arises from the geometrical confinement of fields in the waveguide and have magnitude governed by modal overlap between ordinary and extraordinary modes resulting from scattering at the edges of the waveguide. In this framework, the mode propagation constants in Eq. (1) take the form

Thus, since both coupling constants are typically small, when βe is significantly different than βo, ordinary and extraordinary waveguided modes are relatively independent with βeo+ ≈ βo and βeo− ≈ βe. However, when extraordinary and ordinary modes are degenerate (βe ≈ βo), the effect of mode coupling is important and the resulting hybrid modes βeo have properties from both ordinary and extraordinary modes (e.g., in the HM mode profile in Fig. 1(b)), a situation similar to that of modes composed of skew rays propagating in circular optical fibres13.

It should be noted that, as can be observed from Fig. 1(c), for waveguided mode propagating along the extraordinary z-axis, it is not possible to achieve ordinary and extraordinary modes (defined by the blue and red dispersions, respectively) with the same value of β in the case of hyperbolic dispersion. Therefore, in this case there is no degeneracy between ordinary and extraordinary modes and the mode hybridisation does not occur.

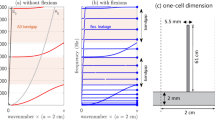

The coupling between ordinary and extraordinary modes in the waveguide was analyzed through the numerical simulations of the behavior of the propagation constant in a MW surrounded by air (ε = 1). The behavior of uncoupled βe and βo follows approximately that of the MW analyzed above using Eqs (5,6) for PEC boundary conditions (cf. Figs 1(d) and 2). In the case of elliptical dispersion (Fig. 2(a)), the degeneracy of the (1, 2) extraordinary mode and the (1, 1) ordinary mode leads to strong coupling resulting in the modification of the mode dispersions in the shape of avoided crossing. The mode profiles simulated for different frequencies show that waveguides with heights for which there is no mode degeneracy, support well-defined extraordinary and ordinary modes, while in the vicinity of the degeneracy point, HM profile is a linear combination of the two (Fig. 2(a)).

Dispersion of the waveguided modes in MW near the degeneracy points in the case of (a) elliptic and (b) hyperbolic dispersions. Solid lines are the full-vectorial numerical simulations: (red) βeo+ and (blue) βeo–. Dashed lines are the model with PEC boundary conditions where coupling is absent: (red) extraordinary and (blue) ordinary modes. The mode profiles are also shown. The metamaterial parameters are as in Fig 1.

A similar analysis in the case of hyperbolic dispersion reveals very different behavior (Fig. 2(b)). For example, strong coupling between (1, 4) extraordinary mode and (1, 1) ordinary mode does not exhibit avoided crossing of the degenerate modes, leading nevertheless to strong interaction between them. The resulting shape of the dispersion curve obtained numerically can also be obtained for the coupling between the ordinary and hyperbolic extraordinary modes using equations Eqs (5, 6, 7) with the coupling constants αeo = γ = 0.01. This peculiar shape is due to the interplay between positive and negative direction of the energy flow in the interacting modes. In this case, the propagation constant of the hybrid modes may have a non-zero imaginary part even in the case of lossless material constants.

This “effective” attenuation, determined by the value of εzz/εxx is a consequence of the competition between the forward waves (ordinary wave components) and the backward waves (extraordinary wave components) in the hybrid waveguided mode. Thus, the mode is allowed to take a backward path through its extraordinary component, leading to a limit in its total propagation length and to its effective attenuation even if, for the sake of the argument, lossless materials are considered.

In a multimode waveguide, multiple degeneracies of ordinary and extraordinary modes exist at different wavelengths, depending on the waveguide dimensions. The coupling strength between the modes depends on the overlap of their fields and is different for different modes. This can be observed in the variations of the effective refractive index neff = β/k0 of the hybrid modes with the height of the waveguide in both the elliptic and hyperbolic case (Fig. 3). For example, in Fig. 3(b), the coupling of 4 hyperbolic extraordinary modes and the ordinary mode is seen with different strength. In turn, a variation of the MW’s width will only lead to a shift of the degeneracy frequency (Eqs (5, 6, 7)). Furthermore, increasing material losses result in the decrease of the coupling strength between extraordinary and ordinary modes (Figs 3(a,b) and 4(a)). As losses increase, βeo+ tends to βo and βeo− to βe.

The dependence of the effective mode index on the height of the waveguide for ordinary, extraordinary and hybrid modes in the case of (a) elliptic and (b) hyperbolic dispersion regime. The modes profiles are also shown. The mode identification is shown in (b). The modes for the metamaterial are simulated with Im(εzz) = 0.1 typical for Au-based nanorod metamaterials and with the loss increased 50 times (Im(εzz) = 5). The waveguide width is fixed at a/λ = 0.3.

(a) Dispersion, (b) group velocity and (c) group velocity dispersion of the hybrid hyperbolic modes (βeo+) for different material losses. The same dependences can be obtained by varying the imaginary part of only εxx or εzz or of both εxx and εzz at the same time. The other waveguide parameters are the same as in Fig. 1.

Since the hybrid modes obtained through the coupling between the extraordinary hyperbolic mode and ordinary elliptic mode exhibit a complex dispersion (Fig. 4(a)), their group velocity and group velocity dispersion have interesting properties. First, in the low loss case, we observe that the hybrid mode βeo+, corresponding to the forward hybrid mode, has two points of low group velocity (Fig. 4(b)). In the lossless case, the amplitudes of the peaks become infinite and the group velocity is zero, corresponding to the so-called stopped-light regime17,18. The reduction of the group velocity is strongly dependent on the losses in the hyperbolic media (red and blue curves in Fig. 4(b) but is present even for unrealistically increased losses. For the artificial hyperbolic metamaterials based on Au nanorod arrays, relevant for the consideration above, the losses can be controlled through the annealing of the electrodeposited gold19 and Im(εzz) is of the order of 0.1 or lower. Smaller values are possible with silver nanorod arrays20. Furthermore, several natural hyperbolic materials, such as hexagonal boron nitride, can provide low-loss hyperbolic behavior21,22, suitable for the observation slow waveguided modes described above.

The stopped-light behavior can be intuitively understood from the competition between ordinary and extraordinary modes with opposite group velocities. Therefore, these metamaterial waveguides can be used for the design of stopped-light lasers23, enhancement of nonlinear effects, optical switching, quantum optics and optical data storage18,24. In particular, in the case of stopped-light lasers, a MW can be designed to achieve stopped light (or slow light considering losses) with large tuneability since the properties of the metamaterial can be designed from its geometry and composing materials, thus allowing the lasing enhancement at any chosen wavelength. Interestingly, low group velocity can also be achieved in planar hyperbolic metamaterial waveguides for pure TM modes7,8,9,10, where the phenomenon has a different nature and related purely to metamaterial dispersion. Similarly, group velocity can be engineered and controlled with loss using interplay between material and waveguide-geometry dependent dispersion in the confined waveguides with the PEC cladding, where the mode coupling is also absent25.

Furthermore, the spectral range of a very high group velocity is also present in the HM dispersion, corresponding to the creation of “superluminal waves”26. These hybrid modes have regions of very strong negative and positive group velocity dispersion (GVD) as is seen in Fig. 4(c). The largest GVD is obtained around the stopped light points, since in this regime, one of the spectral components is stopped while the others are still propagating (i.e., the spectral components of a light pulse). Such strong GVD is suitable for implementing microscale metamaterial inserts in optical fibres to achieve dispersion control for pulse reshaping in optical communications27.

In conclusion, the strong coupling between extraordinary and ordinary modes induced by geometrical confinement in the waveguides made of an anisotropic metamaterial has been studied analytically using first-order perturbation theory and numerical simulations. Such coupling is absent in planar hyperbolic waveguides based on layered or nanorod composites, where TE and TM modes are independent7,8,9. The results show a typical strong coupling behavior in the case of the metamaterial with a conventional elliptic dispersion, whereas in the case of the metamaterial with a hyperbolic dispersion, the strong coupling results in the hybrid modes with anomalous dispersion. This anomalous dispersion exhibits features such as stopped and superluminal regimes, both depending on modal losses. The related GVD shows both positive and negative regimes with large GVD value, several orders of magnitude larger than typical GVD used in, e.g., pulse compression applications. It was also found that strength of the modal coupling can be controlled through the material losses thus, opening perspectives for all-optical control of the coupling, mode dispersion, group velocity and GVD of these hybrid modes via the nonlinear response of metamaterial’s metal component3,28,29. Such metamaterial waveguides can be incorporated in silicon-based photonic circuitry or in optical fibres for all-optical modulation, stopped-light lasing or dispersion compensation applications for on-chip ultrashort pulse generation.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Neira, A. D. et al. Superluminal and stopped light due to mode coupling in confined hyperbolic metamaterial waveguides. Sci. Rep. 5, 17678; doi: 10.1038/srep17678 (2015).

References

Soukoulis, C. M. & Wegener, M. Past achievements and future challenges in the development of three-dimensional photonic metamaterials. Nat. Phot. 5, 523–530 (2011).

Krishnamoorthy, H. N. S., Jacob, Z., Narimanov, E., Kretzschmar, I. & Menon, V. M. Topological transitions in metamaterials. Science 336, 205–209 (2012).

Wurtz, G. A. et al. Designed ultrafast optical nonlinearity in a plasmonic nanorod metamaterial enhanced by nonlocality. Nat. Nanotech. 6, 107–111 (2011).

Pendry, J. B. Negative refraction makes a perfect lens. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 3966–3969 (2000).

Poddubny, A., Iorsh, I., Belov, P. & Kivshar, Y. Hyperbolic metamaterials. Nat. Phot. 7, 948–957 (2013).

Wells, B. M., Zayats, A. V. & Podolskiy, V. A. Nonlocal optics of plasmonic nanowire metamaterials. Phys. Rev. B 89, 035111 (2014).

Vasilantonakis, N., Nasir, M. E., Dickson, W., Wurtz, G. A. & Zayats, A. V. Bulk plasmon-polaritons in hyperbolic nanorod metamaterial waveguides. Laser Phot. Rev. 9, 345–353 (2015).

Hu, H., Ji, D., Zeng, X., Liu, K. & Gan, Q. Rainbow trapping in hyperbolic metamaterial eaveguide. Sci. Rep. 3, 1249 (2013).

Alekseyev, L. V. & Narimanov, E. Slow light and 3D imaging with non-magnetic negative index systems. Opt. Exp. 14, 11184–11193 (2006).

Cortes, C. L. & Jacob, Z. Photonic analog of a van Hove singularity in metamaterials. Phys. Rev. B 88, 045407 (2013).

Dickson, W. et al. Hyperbolic polaritonic crystals based on nanostructured nanorod metamaterials. Adv. Mat. 27, 5974–5980 (2015).

Fleck, J. J. A. & Feit, M. D. Beam propagation in uniaxial anisotropic media. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 73, 920–926 (1983).

Collin, R. E. Field Theory of Guided Waves (Wiley, 1990).

Jackson, J. D. Classical electrodynamics (Wiley, 1975).

Zayats, A. V. & Maier, S. Active Plasmonics and Tuneable Plasmonic Metamaterials (Wiley, 2013).

Engheta, N. & Ziolkowski, R. W. Metamaterials: Physics and Engineering Explorations (Wiley, 2006).

Tsakmakidis, K. L., Pickering, T. W., Hamm, J. M., Page, A. F. & Hess, O. Completely stopped and dispersionless light in plasmonic waveguides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 167401 (2014).

Khurgin, J. B. & Tucker, R. S. Slow Light: Science and Applications (CRC Press, 2008).

Pollard, R. J. et al. Optical nonlocalities and additional waves in epsilon-near-zero metamaterials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 127405 (2009).

Tsai, K.-T. et al. Looking into meta-atoms of plasmonic nanowire metamaterial. Nano Lett. 14, 4971–4976 (2014).

Dai, S. et al. Graphene on hexagonal boron nitride as a tunable hyperbolic metamaterial. Nat. Nanotech. 10, 682–686 (2015).

Yoxall, E. et al. Direct observation of ultraslow hyperbolic polariton propagation with negative phase velocity. Nat. Photon. 9, 674–678 (2015).

Pickering, T., Hamm, J. M., Page, A. F., Wuestner, S. & Hess, O. Cavity-free plasmonic nanolasing enabled by dispersionless stopped light. Nat. Comm. 5, 4972 (2014).

Krauss, T. F. Why do we need slow light? Nat. Phot. 2, 448–450 (2008).

Govyadinov, A. A. & Podolskiy, V. A. Enhancement of dispersion modulation in nanoscale waveguides. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B. 25, C127–C135 (2008).

Wang, L. J., Kuzmich, A. & Dogariu, A. Gain-assisted superluminal light propagation. Nature 406, 277–279 (2000).

Turitsyn, S., Sorokina, M. & Derevyanko, S. Dispersion-dominated nonlinear fiber-optic channel. Opt. Lett. 37, 2931–2933 (2012).

Kauranen, M. & Zayats, A. V. Nonlinear plasmonics. Nat. Phot. 6, 737–748 (2012).

Neira, A. D., Wurtz, G. A., Ginzburg, P. & Zayats, A. V. Ultrafast all-optical modulation with hyperbolic metamaterial integrated in Si photonic circuitry. Opt. Exp. 22, 10987–10994 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported, in part, by EPSRC (UK), the ERC iPLASMM project (321268) and US Army Research Office (W911NF-12-1-0533). A.Z. acknowledges support from the Royal Society and the Wolfson Foundation. G.W. acknowledges support from the EC FP7 project 304179 (Marie Curie Actions). The data access statement: all data supporting this research are provided in full in the results section.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors developed the idea, A.D.N. performed modeling, all the authors analyzed data and prepared the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Neira, A., Wurtz, G. & Zayats, A. Superluminal and stopped light due to mode coupling in confined hyperbolic metamaterial waveguides. Sci Rep 5, 17678 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep17678

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep17678

This article is cited by

-

Experimental investigation of optically controlled topological transition in bismuth-mica structure

Scientific Reports (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.