Abstract

Indole is widely spread in various environmental matrices. Indole degradation by bacteria has been reported previously, whereas its degradation processes driven by aerobic microbial community were as-yet unexplored. Herein, eight sequencing batch bioreactors fed with municipal and coking activated sludges were constructed for aerobic treatment of indole. The whole operation processes contained three stages, i.e. stage I, glucose and indole as carbon sources; stage II, indole as carbon source; and stage III, indole as carbon and nitrogen source. Indole could be completely removed in both systems. Illumina sequencing revealed that alpha diversity was reduced after indole treatment and microbial communities were significantly distinct among the three stages. At genus level, Azorcus and Thauera were dominant species in stage I in both systems, while Alcaligenes, Comamonas and Pseudomonas were the core genera in stage II and III in municipal sludge system, Alcaligenes and Burkholderia in coking sludge system. In addition, four strains belonged to genera Comamonas, Burkholderia and Xenophilus were isolated using indole as sole carbon source. Burkholderia sp. IDO3 could remove 100 mg/L indole completely within 14 h, the highest degradation rate to date. These findings provide novel information and enrich our understanding of indole aerobic degradation processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Research of indole has been drawing increasing concerns recently. It not only acts as the intercellular signal molecule in bacterial systems, but also a plant-growth modulator as well as an interkingdom signal between microbiota and mammalian hosts1,2,3,4. Indole plays diverse signaling roles in controlling virulence, biofilm formation, plasmid stability and stress responses, thus affecting the phenotypes and physiological behaviors of microbes1,5. Studies have shown that indole can directly and rapidly cross bacterial membrane without Mtr, AcrEF-TolC or other transporter proteins, facilitating its microbial and interkingdom signaling functions6. It has been proven that over 85 bacterial species can produce indole from tryptophan due to the existence of tryptophanase1. Furthermore, indole is a genotoxic and recalcitrant N-heterocyclic aromatic pollutant which can be generated in large quantity from coal mining and oil shale operations7,8. Therefore, microbes will inevitably encounter and interact with indole in various matrices, such as wastewater.

Bacteria can produce indole from tryptophan and also harbor the ability to degrade indole. For this regard, initial attempts could be dated back to 1920s, when Raistrick and Clark found that Bacillus spp. could attack indole nucleus and release ammonia9. Afterwards, Sakamoto et al., Fujioka and Wada and Claus and Kutzner further enriched indole degradation pathways using different aerobic bacterial strains10,11,12. In recent years, Pseudomonas and Cupriavidus spp. have also been isolated and characterized for indole degradation13,14,15,16,17. Under aerobic conditions, indole degradation was initiated via hydroxylation at C3 or C2/C3 positions resulting in indoxyl or 2,3-dihydroxyindole formation. Anthranilic acid was the typical intermediate and indigoids were also frequently formed10,11,12,15. Under anaerobic conditions, indole was usually attacked at C2 position with 2-oxindole generation under denitrifying, methanogenic and sulfate-reducing conditions18,19,20. Denitrifying microbial communities could effectively convert the intermediate 2-oxindole leading to a higher indole degradation efficiency20. It is interesting that very limited anaerobic pure microorganisms have been isolated and characterized21. The structures of bacterial communities under denitrifying and sulfate-reducing conditions have been identified using 16S rRNA gene clone libraries22. However, the bacterial community for indole aerobic degradation, which existed ubiquitously, has not been referred yet to the best of our knowledge. With the ongoing development of sequencing technology, it is possible to explore the entire profile of microbial community previously unattainable using high-throughput sequencing technologies. Especially, Illumina sequencing has been widely used due to its low cost and high sequencing depth merits23. Therefore, application of Illumina sequencing will provide huge amounts of useful information to enhance our understanding of indole degradation microbial communities.

Investigations on wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) sludges revealed that core populations existed in either municipal activated sludge or certain type of industrial sludge despite of different geographical locations24,25. Indeed, the microbial community composition and structure are resulted from various factors classified as deterministic and stochastic processes26. Deterministic factors play key roles in community assembly of wastewater treatment systems. Among them, original microbial community structures play a role in community formation processes due to the different interspecies interactions (e.g., commensalism, competition, predation, synergism and tradeoffs) and species traits. From this point, two different types of original sludges from the secondary sedimentation tanks of a local municipal WWTP and a coking WWTP were used in the present study. Since microbes could utilize indole as the sole carbon source or co-metabolize indole in the presence of other carbon sources, three different cases were investigated using sequencing batch reactor systems: (i) co-metabolism with glucose and nitrogen supplementation, (ii) indole as the sole carbon source with nitrogen supplementation and (iii) indole as the sole carbon and nitrogen source. Meanwhile, isolation of pure cultures in each operation stage was also conducted to obtain available indole-degrading resources, which could be a supplement for the metagenomic sequencing. The main goal of present study was to comprehensively and systematically reveal indole aerobic degradation microbial communities, enriching our understanding of indole-degrading processes.

Results

Performance of the indole-degrading bioreactors

The construction and operation processes of the reactors were shown in Fig. 1. Two types of activated sludges, i.e. municipal sludge (system A) and industrial sludge (system B), were gathered and operated in quadruplicate. Overall, indole and chemical oxygen demand were removed completely within every operation cycle. The sludge samples at each final stage were centrifuged and the pellets were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide. Apparently, the product colors differed between the two sludge systems (Figure S1). System A displayed dark brown while system B was blue, similar with our previous study27. The products were further analyzed using high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS) and HPLC analyses (Figure S2). Indigo (retention time 17.9 min) with m/z of 261.067 (M-H–) was the major product in both systems at any stage. Indirubin (retention time 22.5 min), an isomer of indigo, was also formed although in low production. It was found that at least three substances with m/z 261.067 (M-H–) were detected in both systems at any stage, indicating that some other indigoids were also produced besides indigo and indirubin. These findings indicated that the distinct colors of system A and B should be resulted from different proportions of these products.

Experimental design of indole aerobic degrading processes.

Two kinds of activated sludge were adopted and each sludge was operated in quadruplicate. The whole operation processes contained three stages and each stage lasted for two months. Stage I, indole and glucose were the carbon source and NH4Cl was the nitrogen source. Stage II, indole was the sole carbon source and NH4Cl was the nitrogen source. Stage III, indole was the sole carbon and nitrogen source. The influent indole concentration was 200 mg/L throughout the experiment. MS medium stands for mineral salt medium.

Overview of the 16S rRNA high-throughput sequencing results

After sequence treatment, 10,833–56,298 clean reads were obtained for each sample which were then set a resample at 10,000 for following analysis. Richness and alpha diversity of the microbial community indicated by Chao1 value, OTU number, Shannon and Simpson indexes were calculated as shown in Table 1. For system A, the total OTU numbers and Chao1 values of the original sludge, 629 ± 8 and 800 ± 56, were much higher than those of other stages. Shannon index and Simpson index data demonstrated that indole could significantly reduce sludge diversity with the diversity order of original sludge > Stage I > Stage II > Stage III, the same as the OTU and Chao1 numbers. As the case of system B, a similar trend was exhibited with system A except that the diversity in stage I was higher than original one. Overall, richness and diversity of both systems in stage II and stage III were very low with Chao1 183–324, OTU 108–188, Shannon index 1.73–2.54 and Simpson index 0.16–0.31.

The non-metric dimensional scaling (NMDS) ordination plot which depicted microbial community differences at OTU level was shown in Fig. 2. Microbial communities with indole dosing were clearly different from that of original sludge and the communities changed with operation stages from left to right in Axis 1 direction. At stage I, microbial communities of A and B were clearly separated. The points for stage II and stage III were mixed with each other, implying that microbial communities at these stages might be similar to a certain degree. Heat map plot at OTU level (Figure S3) showed that microbial community clearly shifted from the original ones. Meanwhile, the quadruplicate samples of any group clustered together, suggesting the results were credible. Three significance tests, i.e. MRPP, ANOSIM and Adonis, were conducted to analyze the differences of sludge communities at each stage (Table 2). P value less than 0.05 meant a significant difference between the communities. Although microbial communities of system A and B exhibited similar variation tendency according to NMDS plot, dissimilarity analyses declared that sludge communities were significantly distinct from each other of each stage (All P < 0.05). The communities of system A and B at same stage were also notably different.

Bacterial communities of original sludge

The microbial compositions and structures of the two sludge systems at phylum, class and genus level were analyzed in detail (Fig. 3, Figure S4). Obviously, the original community of system A and B were quite different. Proteobacteria (51.66%) and Bacteroidetes (24.64%) were the dominating phyla in system A, while Proteobacteria (71.96%) and Acidobacteria (11.08%) dominated in system B. Typical genera in municipal sludge, such as Zoogloea (2.57%), Dechloromonas/Ferribacterium (9.85%), Gp4 (2.65%) and Prosthecobacter (2.73%), were detected as the main components in system A as well.Genus Thiobacillus (35.80%) was the foremost component in system B, which was responsible for denitrification and thiocyanate biodegradation processes ubiquitously appeared in coking WWTPs. This result was consistent with previous studies on WWTP sludges using high-throughput sequencing24,25.

Major genera of all groups.

Major means sequence percentage is above 1% in any group. A0, A1, A2, A3 stand for the samples of original, stage I, stage II and stage III of system A. B0, B1, B2, B3 stand for the samples of original, stage I, stage II and stage III of system B. The redder the color, the higher the percentages and the bluer the color, the lower the percentages.

Bacterial communities using glucose-indole as co-substrate

After a course of two-month operation feeding glucose-indole and NH4Cl as the carbon and nitrogen sources, both sludge communities significantly shifted. Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes and Acidobacteria were the major phyla in both sludges. At genus level, Azoarcus was the primary component in system A, accounting for 37.81% of the total sequences. Other major genera included TM7_genera_incertae_sedis (6.29%), Terrimonas (4.99%), Nakamurella (4.07%), Lysobacter (4.61%), Sphigopyxis (3.62%) and Comamonas (3.20%). Genera such as Zoogloea, Dechloromonas/Ferribacterium, Gp4 and Prosthecobacter which were dominating in original sludge were absent in this stage. In system B, Thauera and Azoarcus were the two primary genera with sequence percentages of 12.73% and 11.61%, respectively. Thiobacillus decreased dramatically from 35.80% (original sludge) to 0.01% (stage I). Alcaligenes and Burkholderia were hardly detected in both systems in stage I and Comamonas was in a modest proportion with percentage of 3.31%.

Bacterial communities using indole as the sole carbon source

After continuous dosing of indole and NH4Cl as the carbon and nitrogen sources for another two months, bacterial community experienced a great change in both systems compared with those of stage I. The two systems harbored similar components at high taxonomic level. Both systems contained four major classes, i.e. Betaproteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria and Sphingobacteria, among which Betaproteobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria were extraordinary dominant (over 87%). However, community structures differed from each other at low taxonomic level. Comamonas increased to be the foremost genus in system A, accounting for 25.71% of the total sequences, followed by Pseudomonas (8.89%), Sphingopyxis (6.01%), Azoarcus (4.83%), Pusillimonas (4.68%), Lysobacter (3.76%), Rhodanobacter (1.47%), Sphingomonas (1.42%) and Dokdonella (1.29%). It was worth noting that Azoarcus decreased from 37.81% to 4.83%. For system B, the two hardly detected genera in stage I, Alcaligenes and Burkholderia, became the core genera accounting for 29.44% and 28.65%, respectively. Other major genera contained Comamonas (4.74%), Sphingopyxis (2.22%) and Rhodanobacter (1.13%). Thauera, the predominate genus in stage I (12.73%), occupied only 0.44% in this stage.

Bacterial community using indole as the sole carbon and nitrogen source

At the final stage, bacterial composition and structure were similar with those of stage II at phylum and class levels in both systems. Alcaligenes increased continuously reaching 20.02% and 49.41% in system A and B, respectively, while Azozrcus decreased continuously to be the minor genus in both systems (0.36% in A and 0.01% in B). Comamonas also decreased to some extent with percentages of 8.93% and 2.56% in sludge A and B, respectively. Burkholderia was still scarce in system A (0.21%) but dominating in system B (20.38%). Other major genera in system A contained Pseudomonas (4.98%), Cupriavidus (4.71%), Lysobacter (3.17%), Variovorax (2.85%), Ferruginibacter (2.10%), Rhodanbacter (1.82%), Sphingopyxis (1.31%) and Sphingonmonas (1.04%). Cupriavidus was increasing as the major genus for the first time in system A, but absent in system B. Pseudomonas was still acting as a major component in system A which was also sporadic in system B. In system B, Alcaligens, Burkholderia and Comamonas were the only three major genera.

Degradation of indole by isolated pure cultures from the reactors

To further explore microbial resources for indole degradation, we have tried to isolate pure indole degraders from these systems. Totally four strains, designated as IDO1, IDO2, IDO3 and IDO4 were obtained. Nearly the complete 16S rRNA gene sequences were obtained and they were identified as Comamonas sp., Comamonas sp., Burkholderia sp. and Xenophilus sp., respectively. According to the 16S rRNA gene sequences, a phylogenetic tree was constructed with the sequences of other indole degrading bacteria (Fig. 4A). Comamonas could be isolated at each stage of the operation, Burkholderia was obtained at stage II and stage III and Xenophilus was only isolated in stage III (Table S1). This was in accordance with the Illumina sequencing data that Comamonas was abundant throughout the stages and Burkholderia was emerging at stage II. However, other reported indole degrading bacteria, such as Alcaligenes spp., Pseudomonas spp. and Cupriavidus spp., were not obtained, which might be due to the restriction of present isolation method.

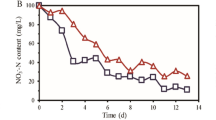

Phylogenetic tree (a) and indole degradation curves (b) of the four isolated indole bacteria.

Phylogenetic tree was constructed using neighbor-joining method and numbers indicated the bootstrap values derived from 1000 replicates. Except for E. coli, all strains are reported indole degrading bacteria. Sequences were aligned using Clustal X 1.8 and MEGA 5.0 was used to construct phylogenetic tree.

The indole-degrading characteristics of the four strains were investigated. All four strains could use indole as the sole carbon and nitrogen source, although the isolation medium contained NH4Cl as the nitrogen source. Commonas sp. IDO1 and IDO2 could transform indole and yield yellow substances, but bacterial density was quite low with hardly increased OD600 values. Xenophilus sp. IDO4 also produced yellowish products. The degradation efficiencies of these three strains were not comparable and almost one week was required to remove 100 mg/L indole. Burkholderia sp. IDO3 could utilize indole efficiently and remove 100 mg/L indole within 14 h, whose efficiency was the highest to date (Fig. 4B).

Discussion

Concerns on indole have been exponentially increasing in recent years for its important roles in pharmaceutical industry and signaling functions1,3,28. However, indole transformation is actually an unrevealed and complicated process yet to be fully understood. For instance, many unidentified metabolites catalyzed by P450 hydroxylase and phenol hydroxylase were observed29,30, indole-degrading functional genes or gene clusters have never been acquired11,31 and indole aerobic degrading microbial communities have not been fully explored yet27. In this study, it was proven that indole could be effectively degraded in SBR activated sludge systems. Degradation efficiency (200 mg/L indole completely removed within two days) was much higher than that of anaerobic sludge systems18,19,20. HPLC-MS analysis verified that indigoids were produced and accumulated, which was in accordance with our previous study27. Production of indigo and its isomers suggested indole should be oxidized at C3 position leading to indoxyl generation, the precursor of indigo32. C3 position is more vulnerable and active than C2 thus easier attacked by oxygen catalyzed by aromatic oxygenases. Under anaerobic conditions, C2 was generally hydroxylated with 2-oxindole production which could be accumulated under methanogenic and sulfate-reducing but not under denitrifying conditions20,33. In both cases, the functional oxygenases for indole-degrading microbes have not been acquired to date.

Indole is toxic to organisms including microbes. It can cause membrane derangement and high concentration of indole may inhibit energy production and protein folding by a transcriptomic and in vitro protein-refolding assay34,35. Meanwhile, studies have shown that indole is a proton ionophore which can arrest bacterial growth and cell division36. Therefore, indole as an exogenous stress would negatively affect some bacterial species. The diversity and richness of both system A and B decreased significantly, while it was not the case for stage I of system B whose diversity and richness were higher than original sludge. Sludge B was adopted from coking WWTP, where the wastewater contained large amount of inorganic and organic pollutants, such as phenol, naphthalene, indole, quinolone and pyridine24,37. In stage I, the influent was mineral salt medium, glucose and indole, which was less complicated than real coking wastewater. Hence, the influent might be less toxic than real coking wastewater leading to the higher alpha diversity and richness in reactor sludge.

Dominant species for indole degradation under the three investigated conditions were notably different, particularly for stage I with glucose and indole as the carbon sources (Fig. 5). Azoarcus (37.81%) was the most abundant genus in system A and Azoarcus (11.61%) and Thauera (12.73%) were the top two genera in system B. Thauera and Azoarus were two functionally important and closely related species often occurred together responsible for denitrifying in activated sludge38. They also exhibited versatile degradation capacities towards a variety of aromatics24. Previous studies indicated that Thauera spp. could utilize indole as the sole carbon source under anaerobic conditions39,40. Hong et al. constructed a denitrifying reactor fed with indole and glucose as carbon sources and Thauera was among the abundant genera revealed by 16S rRNA gene clone library analysis22. Afterwards, they isolated three Thauera spp. from a coking WWTP, all of which could degrade indole under aerobic conditions41. Taken together, these results suggested Thauera spp. were the common indole degraders in microbial community especially in the presence of other carbon sources. Azoarus was also identified as a frequent aromatic (e.g. quinoline) degrader in activate sludge42. Although reports on the degradation of indole by Azoarus were limited, the high proportion of this genus in stage I might be an evidence of its indole degradation potential.

The bacterial community compositions and core genera of stage II and III were similar to some extent. Alcaligenes was the key species in both sludge and increased to be the foremost genus in stage III. Indole degradation by Alcaligens has been documented previously and it was also dominant in the indole denitrifying sludge conducted by Hong et al.12,22. We have also conducted another bioaugmented indole degrading systems and found that Alcaligenes was increasing continuously and even reaching over 50% finally43. Thus Alcaligenes might be the functionally important indole degrading bacterial species in activated sludge systems. Comamonas was major in both systems throughout the operations with proportions 2.74–25.71%. Although it is an amazing aromatic degrading genus widespread in nature, it has never reported to be able to degrade indole yet24,25,27,44. Pseudomonas, the most studied species for indole degradation13,14,45, was dominant in system A (8.89% stage II and 4.98% stage III) but almost negligible in system B. On the contrary, Burkholderia, another well-known aromatic-degrading genus, was the main component in system B (28.65% stage II and 20.38% stage III) but negligible in system A. The research of Burkholderia on indole degradation has also been reported, which, however, could only co-metabize indole46. Since the operational and environmental conditions of these two systems were identical throughout the experiment, it could be concluded that original sludge composition and structure, accompanied by different interspecies interactions and species traits, would affect the community assemble processes. It was clearly shown that the microbial community composition and structure in stage II & III were significantly distinct from stage I. When indole was co-metabolized, Thauera and Azoarus were the major bacteria, while the typical aromatic degraders such as Alcaligenes, Burkholderia and Pseudomonas dominated the community when indole was utilized as sole carbon source. Understanding of indole degradation genetic mechanisms using metaproteomic and metatranscriptomic analyses is a valuable topic that has not been explored yet and the corresponding indole oxygenases in the sludges should have a potential application in industrial field.

Four bacterial strains that could use indole as sole carbon and nitrogen source were isolated. 16S rRNA gene analysis indicated that they belonged to Comamonas, Burkholderia and Xenophilus, all of which have not been reported to assimilate indole as sole carbon source. Comamonas and Burkholderia were the major genera in the microbial communities and their capacity for indole degradation further proved their functions in SBR systems. Through indole degradation curves, it was clearly shown that Burkholderia sp. IDO3 could degrade indole very efficiently. It could completely remove 100 mg/L indole within 14 h, the highest indole degradation rate to date16,17,47. Alcaligenes and Pseudomonas, two typical genera capable for indole degradation, were not obtained in the present study. The possible reason might be that the screening medium was not suitable for strain growth. Another genus, i.e. Cupriavidus, was also not obtained though its proportion in stage III of system A reached 4.71%. At the same time of present work, we also tried to isolate more indole degrading resources from other soil and sludge samples. Two strains named Cupriavidus sp. SHE and Cupriavidus sp. IDO were gained with superior indole degrading performance16,17. Indole degradation by these pure-culture strains displayed two different phenomena. Some strains transformed indole into yellowish products with limited strain growth (e.g., Comamonas sp. IDO1, Comamonas sp. IDO2 and Cupriavidus sp. SHE), while others could utilize indole more effectively and grow very well with production of indigoids (e.g., Cupriavidus sp. IDO and Burkholderia sp. IDO3). The different degradation performances might be due to the genetic differences of these strains. However, studies on indole degradation are just focused on strain isolation and metabolite identification and attempts to identify the functional indole hydroxylase or dioxygenase have not been successful. To in-depth explore the underlying genetic mechanism of indole degradation, a combination of genomic and proteomic experiment was in progress.

In summary, culture-independent high throughput sequencing and culture-dependent methods were utilized to reveal the microbial composition and structure of two indole aerobic degradation sludge communities, i.e. municipal sludge system and coking sludge system, for the first time. Azoarcus and Thauera were the major genera when indole was co-metabolized with glucose as additional carbon source. When indole was added as the sole carbon source, Alcaligenes, Comamonas and Pseudomonas were the core species in municipal sludge system, while Alcaligenes, Burkholderia and Comamonas were the major genera in coking sludge systems. Four strains belonged to Comamonas, Burkholderia and Xenophilus were also isolated from the sludge systems and exhibited excellent efficiency for aerobic indole degradation, especially for Burkholderia.

Materials and Methods

Reactor design and operation

Municipal and industrial activated sludges were gathered from the secondary sedimentation tanks of Chunliu River WWTP (Dalian, China) and Benxi steel coking WWTP (Benxi, China). The sludges were stored at −4 °C immediately after sampling. Eight sequencing batch reactors (SBRs) with working volume of 1.0 L were constructed, among which four replicates were set for each kind of sludge. Mineral salt (MS) medium in the present study composed of (mg/L) 40 KH2PO4, 180 NH4Cl, 5 NaCl, 25 MgSO4·7H2O, 24 CaCl2, 20 FeSO4·7H2O. The SBRs were operated for six months, which were divided into three stages (2 months per stage). Stage I, influent was MS medium, 400 mg/L indole and 1000 mg/L glucose; stage II, influent was MS medium and 400 mg/L indole; stage III, influent was NH4Cl-free MS medium and 400 mg/L indole. Before operation, the sludges were acclimated for two weeks using stage I influent. Each cycle of the SBRs was 48 h, containing 43 h aeration, 4 h settling, 0.5 h decant and 0.5 h fill. In each cycle, half of the sewage was discharged manually and equal volume of fresh medium was replenished, thus the final indole concentration was 200 mg/L. All SBRs were operated under identical conditions.

DNA extraction and pyrosequencing

Original activated sludge and sludge samples at the final cycle of each stage were collected and stored at −80 °C before use. The genomic DNA was extracted using PowerSoil® DNA Isolation Kit (MO BIO laboratories, CA USA). Concentration of DNA was determined by Nano drop. Primers 515F (5′-GTG CCA GCM GCC GCG GTA A-3′) and 806R (5′-GGA CTA CHV GGG TWT CTA AT-3′) with different barcodes for the V4 region of 16S rRNA gene were used for sequencing48. DNA library was constructed and run on the Miseq Illumina.

Pyrosequencing result analysis

The raw sequences were joined and treated as previous described24. Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were generated by UPARSE program. The taxonomic assignment was conducted using RDP classifier with a confidence cutoff of 0.5. The figures were drawn using SigmaPlot 11.0 and Excel. For statistical analysis, the data for each group were the average of its quadruplicate values.

Strain isolation, identification and degradation analysis

Indole-degrading strains were isolated from the activated sludge samples of each stage. Isolation medium consisted of (g/L) 2.0 (NH4)2SO4, 2.0 KH2PO4, 3.28 Na2HPO4·12H2O and 0.00025 FeCl3 was used for strain screening. The activated sludges from each stage were utilized to screen pure cultures using serial dilution method. Finally, four stains were obtained which could use indole as the sole carbon and energy source. 16S rRNA genes of the isolated strains were amplified using universal primers and sequenced in Sangon Biotech Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The sequences were aligned by Clustal X 1.8 and phylogenetic tree was obtained by MEGA 5.0. The strain growth and indole degradation experiments were conducted in 100 mL reaction systems under the condition of 30 °C and 150 r/min. The degradation medium consisted of (g/L) 0.1 MgSO4, 2.0 KH2PO4, 3.28 Na2HPO4·12H2O and 0.00025 FeCl3, which did not contain extra nitrogen source. The original inoculum size was 5% and samples were taken at certain intervals for strain growth and indole concentration determination.

Analytical methods

Indole concentration was measured by HPLC analysis (Hitachi Primaide, Japan)27. Strain growth was characterized by optical density at 660 nm (OD660) using UV-vis spectrophotometer (Metash UV-9000, China). The indole transformation products at the final cycle of each stage were analyzed using HPLC-MS analysis on a quadrupole ion trap instrument (Agilent HP 1100 LC/MSD, USA) equipped with an atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI) source.

Additional Information

Accession codes: The 16S rRNA gene sequences of IDO1, IDO2, IDO3 and IDO4 were deposited in GenBank under accession number of KP895478, KP895479, KP895480 and KP895481 respectively. The raw sequencing data of the present study have been submitted to NCBI Sequence Read Archive (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/) with the project accession number of SRP2052567.

How to cite this article: Ma, Q. et al. Systematic investigation and microbial community profile of indole degradation processes in two aerobic activated sludge systems. Sci. Rep. 5, 17674; doi: 10.1038/srep17674 (2015).

References

Lee, J. H. & Lee, J. Indole as an intercellular signal in microbial communities. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 34, 426–444 (2010).

Wang, D., Ding, X. & Rather, P. N. Indole can act as an extracellular signal in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183, 4210–4216 (2001).

Erb, M. et al. Indole is an essential herbivore-induced volatile priming signal in maize. Nat. Commun. 10.1038/ncomms7273 (2015).

Bansal, T., Alaniz, R. C., Wood, T. K. & Jayaraman, A. The bacterial signal indole increases epithelial-cell tight-junction resistance and attenuates indicators of inflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 228–233 (2010).

Wood, T. K. Insights on Escherichia coli biofilm formation and inhibition from whole-transcriptome profiling. Environ. Microbiol. 11, 1–15 (2009).

Piñero-Fernandez, S., Chimerel, C., Keyser, U. F. & Summers, D. K. Indole transport across Escherichia coli membranes. J. Bacteriol. 193, 1793–1798 (2011).

Fetzner, S. Bacterial degradation of pyridine, indole, quinoline and their derivatives under different redox conditions. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 49, 237–250 (1998).

Kamath, A. V. & Vaidyanathan, C. S. Biodegradation of indoles. Indian Inst. Sci. 71, 1–24 (1991).

Raistrick, H. & Clark, A. B. Studies on the cycloclastic power of bacteria: Part II. A quantitative study of the aerobic decomposition of tryptophan and tyrosine by bacteria. Biochem. J. 15, 76–82 (1921).

Sakamoto, Y., Uchida, M. & Ichihara, K. The bacterial decomposition of indole. I. Studies on its metabolic pathway by successive adaptation. Med. J. Osaka Univ. 3, 477–486 (1953).

Fujioka, M. & Wada, H. The bacterial oxidation of indole. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 158, 70–78 (1968).

Claus, G. & Kutzner, H. J. Degradation of indole by Alcaligenes spec. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 4, 169–180 (1983).

Doukyu, N., Arai, T. & Aono, R. Effects of organic solvents on indigo formation by Pseudomonas sp. strain ST-200 grown with high levels of indole. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 62, 1075–1080 (1998).

Yin, B., Gu, J. D. & Wan, N. Degradation of indole by enrichment culture and Pseudomonas aeruginosa Gs isolated from mangrove sediment. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 56, 243–248 (2005).

Fukuoka, K., Tanaka, K., Ozeki, Y. & Kanaly, R. A. Biotransformation of indole by Cupriavidus sp. strain KK10 proceeds through N-heterocyclic- and carbocyclic-aromatic ring cleavage and production of indigoids. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 97, 13–24 (2015).

Ma, Q., Qu, Y., Zhang, Z., Li, P. & Tang, H. Genome sequence of an efficient indole-degrading bacterium, Cupriavidus sp. strain IDO, with potential polyhydroxyalkanoate production applications. Genome Announc. 3, e00102–15 (2015).

Qu, Y. et al. Biodegradation of indole by a newly isolated Cupriavidus sp. SHE. J. Environ. Sci. 34, 126–132 (2015).

Wang, Y. T., Suidan, M. T. & Pfeffer, J. T. Anaerobic biodegradation of indole to methane. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 48, 1058–1060 (1984).

Madsen, E. L. & Bollag, J. M. Pathway of indole metabolism by a denitrifying microbial community. Arch. Microbiol. 151, 71–76 (1988).

Shanker, R. & Bollag, J. M. Transformation of indole by methanogenic and sulfate-reducing microorganisms isolated from digested sludge. Microb. Ecol. 20, 171–183 (1990).

Johansen, S. S., Licht, D., Arvin, E., Mosbak, H. & Hansen, A. B. Metabolic pathways of quinoline, indole and their methylated analogs by Desulfobacterium indolicum (DSM 3383). Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 47, 292–300 (1997).

Hong, X. et al. Structural differentiation of bacterial communities in indole-degrading bioreactors under denitrifying and sulfate-reducing conditions. Res. Microbiol. 161, 687–693 (2010).

Qu, Y. et al. Responses of microbial communities to single-walled carbon nanotubes in phenol wastewater treatment systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 4627–4635 (2015).

Ma, Q. et al. Bacterial community compositions of coking wastewater treatment plants in steel industry revealed by Illumina high-throughput sequencing. Bioresour. Technol. 179, 436–443 (2015).

Wang, X., Hu, M., Xia, Y., Wen, X. & Ding, K. Pyrosequencing analysis of bacterial diversity in 14 wastewater treatment systems in China. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 7042–7047 (2012).

Zhou, J. et al. Stochasticity, succession and environmental perturbations in a fluidic ecosystem. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 111, E836–E845 (2014).

Zhang, X. et al. Illumina MiSeq sequencing reveals diverse microbial communities of activated sludge systems stimulated by different aromatics for indigo biosynthesis from indole. PLoS ONE 10, e0125732 (2015).

de Sá Alves, F. R., Barreiro, E. J. & Fraga, C. A. From nature to drug discovery: the indole scaffold as a ‘privileged structure’. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 9, 782–793 (2009).

Gillam, E. M., Notley, L. M., Cai, H., De Voss, J. J. & Guengerich, F. P. Oxidation of indole by cytochrome P450 enzymes. Biochemistry 39, 13817–13824 (2000).

Qu, Y. et al. Optimization of indigo production by a newly isolated Pseudomonas sp. QM. J. Basic Microbiol. 52, 687–694 (2012).

Kamath, A. V. & Vaidyanathan, C. S. New pathway for the biodegradation of indole in Aspergillus niger. Appl. Environ.Microbiol. 56, 275–280 (1990).

Ensley, B. D. et al. Expression of naphthalene oxidation genes in Escherichia coli results in the biosynthesis of indigo. Science 222, 167–169 (1983).

Gu, J. D. & Berry, D. F. Degradation of substituted indoles by an indole-degrading methanogenic consortium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57, 2622–2627 (1991).

Garbe, T. R., Kobayashi, M. & Yukawa, H. Indole-inducible proteins in bacteria suggest membrane and oxidant toxicity. Arch. Microbiol. 173, 78–82 (2000).

Kim, J., Hong, H., Heo, A. & Park, W. Indole toxicity involves the inhibition of adenosine triphosphate production and protein folding in Pseudomonas putida. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 343, 89–99 (2013).

Chimerel, C., Field, C. M., Pinero-Fernandez, S., Keyser, U. F. & Summers, D. K. Indole prevents Escherichia coli cell division by modulating membrane potential. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1818, 1590–1594 (2012).

Sun, W. L., Qu, Y. Z., Yu, Q. & Ni, J. R. Adsorption of organic pollutants from coking and papermaking wastewaters by bottom ash. J. Hazard. Mater. 154, 595–601 (2008).

Thomsen, T. R., Kong, Y. & Nielsen, P. H. Ecophysiology of abundant denitrifying bacteria in activated sludge. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 60, 370–382 (2007).

Anders, H. J., Kaetzke, A., Kämpfer, P., Ludwig, W. & Fuchs, G. Taxonomic position of aromatic-degrading denitrifying pseudomonad strains K 172 and KB 740 and their description as new members of the genera Thauera, as Thauera aromatica sp. nov. and Azoarcus, as Azoarcus evansii sp. nov., respectively, members of the beta subclass of the Proteobacteria. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45, 327–333 (1995).

Mechichi, T., Stackebrandt, E., Ga d’on, N. & Fuchs, G. Phylogenetic and metabolic diversity of bacteria degrading aromatic compounds under denitrifying conditions and description of Thauera phenylacetica sp. nov., Thauera aminoaromatica sp. nov. and Azoarcus buckelii sp. nov. Arch.Microbiol. 178, 26–35 (2002).

Mao, Y., Zhang, X., Xia, X., Zhong, H. & Zhao, L. Versatile aromatic compound-degrading capacity and microdiversity of Thauera strains isolated from a coking wastewater treatment bioreactor. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 37, 927–934 (2010).

Liu, B. et al. Thauera and Azoarcus as functionally important genera in a denitrifying quinoline-removal bioreactor as revealed by microbial community structure comparison. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 55, 274–286 (2006).

Qu, Y. et al. Microbial community dynamics and activity link to indigo production from indole in bioaugmented activated sludge systems. PloS ONE 10, e0138455 (2015).

Qu, Y. et al. Indigo biosynthesis by Comamonas sp. MQ. Biotechnol. Lett. 34, 353–357 (2012).

Li, P., Tong, L., Liu, K., Wang, Y. & Wang, Y. Indole degrading of ammonia oxidizing bacteria isolated from swine wastewater treatment system. Water Sci. Technol. 59, 2405–2410 (2009).

Kim, D., Sitepu, I. R. & Hashidoko, Y. Induction of biofilm formation in the betaproteobacterium Burkholderia unamae CK43B exposed to exogenous indole and gallic acid. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 4845–4852 (2013).

Chen, Y., Xie, X. G., Ren, C. G. & Dai, C. C. Degradation of N-heterocyclic indole by a novel endophytic fungus Phomopsis liquidambari. Bioresour. Technol 129, 568–574 (2013).

Bates, S. T. et al. Examining the global distribution of dominant archaeal populations in soil. ISME J. 5, 908–917 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21176040 and 51508068), the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (No. NCET-13-0077), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. DUT14YQ107) and the Open Project of State Key Laboratory of Urban Water Resource and Environment, Harbin Institute of Technology (No. ESK201529). We acknowledge Longchao Cong (DUT) for sample collection and measurement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Q. and Q.M. conceived and designed the project and experiments. Q.M., X.Z., Z.L. and H.L. performed the experiments of reactor construction and operation. Z.Z., J.W. and W.S. participated in sample and data collection. Q.M. analyzed the data. Y.Q. and J.Z. contributed to discussion. The manuscript was written by Q.M. and reviewed by all co-authors.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, Q., Qu, Y., Zhang, X. et al. Systematic investigation and microbial community profile of indole degradation processes in two aerobic activated sludge systems. Sci Rep 5, 17674 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep17674

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep17674

This article is cited by

-

Performance and Microbial Community Analysis of Bioaugmented Activated Sludge System for Indigo Production from Indole

Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology (2019)

-

Performance and microbial community dynamics of electricity-assisted sequencing batch reactor (SBR) for treatment of saline petrochemical wastewater

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2017)

-

Performance and microbial community composition in a long-term sequential anaerobic-aerobic bioreactor operation treating coking wastewater

Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.