Abstract

In this study, the electrodeposition (ED) of ultrathin, compact TiO2 blocking layers (BLs) on fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) glass for perovskite solar cells (PSCs) is evaluated. This bottom-up method allows for controlling the morphology and thickness of TiO2 films by simply manipulating deposition conditions. Compared with BLs produced using the spin-coating (SC) method, BLs produced using ED exhibit satisfactory surface coverage, even with a film thickness of 29 nm. Evidence from cyclic voltammetry shows that an ED BL suppresses interfacial recombination more profoundly than an SC BL does, consequently improving the photovoltaic properties of the PSC significantly. A PSC equipped with an ED TiO2 BL having a 13.6% power conversion efficiency is demonstrated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the organo-lead halide perovskite light absorber was reported in 20091, the perovskite solar cell (PSC) has developed into a promising category in the photovoltaic territory. Since the first PSC with a double-digit power conversion efficiency (PCE) having an analogous structure to solid-state dye-sensitised solar cells was reported in 20122, the device architecture of the PSC has been broadened to include several format, such as extremely thin absorber cells2, meso-superstructured solar cells3 and planar heterojunction cells4,5. Planar junction PSCs with an extremely high PCE (over 20%) have been demonstrated and certificated by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, USA (http://www.nrel.gov/). Within only five years, PSCs have become a viable competitor to conventional silicon-based photovoltaics. In a typical PSC, when incident light is absorbed by organo-lead halide perovskite, photo-generated electron-hole pairs are separated and then injected into n-type and p-type semiconductors, respectively. Since carriers are transported via different routes and collected at two terminals, careful control of the various materials and interfaces, including the blocking layer (BL)5,6,7, the perovskite layer8,9,10 and the hole transport layer11,12,13, is critical to achieving a high PCE.

Among the various materials and interfaces, the BL refers to the individual layer between the transparent conductive substrate and the light absorbing layer. The BL plays a crucial part in the PSC because it prevents carriers from directly contacting the conductive substrate and thereby shunting the device. Such a charge recombination has been proven to lower charge collection efficiency and leads to lowering the short circuit current (JSC) as well as the fill factor (FF) on the current–voltage (IV) characteristic curve of a PSC6. TiO2 is the most frequent BL material used14, although zinc oxide15 and cesium carbonate16 are also high-performing materials. Spin coating (SC) and spray pyrolysis (SP) are two representative solution processes used to form BLs4,17,18,19, although atomic layer deposition (ALD)6, thermal oxidation20 and TiCl4 chemical bath deposition21 have also been reported in the literature. SC involves dipping a few solution containing a dilute titanium precursor onto a vacuum-suctioned fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) substrate, then spinning the shaft and baking the substrate sequentially to form the film. SP involves using an atomiser to spray a titanium precursor onto a heated substrate; the precursor droplets thermally decompose simultaneously to form the film. It is generally acknowledged that the quality of BLs produced through either SC or SP is highly sensitive to process parameters and thus the PCE can vary substantially even when applying the same BL process. Ideally, a BL should be pinhole-free and compact at very thin thicknesses to avoid additional resistive losses. In practice, producing perfectly covered films on such a small scale continues to be challenging22. Both SC and SP are top–down strategies: the TiO2 precursor is randomly driven by auxiliary forces from the bulk area to the substrate surface; these methods thus lack the controllability to form a naturally continuous film. Satisfactory coverage is usually accomplished by increasing the film thickness, which simultaneously increases the internal resistance of the device.

ED is a bottom-up methodology that provides a contour-chasing capability because the electrochemical reaction occurs on the electrode surface. In contrast to other bottom-up methods such as ALD, ED is a simple, cost-effective and scalable method to obtain a continuous and uniform surface coating without the need for a high temperature treatment or vacuum environment. More important, compared with ALD, the deposition rate of ED is one order of magnitude higher than ALD, which is advantageous when considering mass production of PSC in the future. Moreover, by manipulating the parameters of ED, both film thickness and morphology can be easily controlled. Kavan et al. reported that TiO2 can be formed through the fast hydrolysis of Ti3+ in an acid solution followed by a galvanic reaction, resulting in a perfectly covered TiO2 layer23. Wu et al. applied this method not only to deposit a TiO2 BL on the FTO surface24,25 but also to modify the connection of TiO2 nanoparticles26 for dye-sensitised solar cells. In this article, we apply ED from an aqueous TiCl3 solution to prepare a BL on an FTO glass for TiO2-scaffold type PSCs for the first time. Characterisations from field-emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM), secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) and cyclic voltammetry (CV) show that the ED BL is thinner and denser; it thus exhibits an enhanced blocking performance compared with an SC BL. As a result, PSCs equipped with ED BLs outperform those equipped with SC BLs by more than 3% in PCE.

Results & Discussion

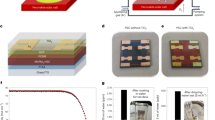

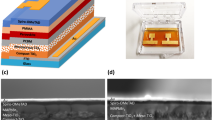

First, the identity of ED TiO2 film was confirmed by X-ray diffractometer. To enhance the diffraction signal, we purposely electrodeposited a thick TiO2 film by extending deposition time to 4000 seconds. As shown in Fig. S1, diffraction peaks assigned for the anatase TiO2 (JCPDS card no.86-1155) appeared after annealing ED TiO2 at 450 °C for 30 minutes, confirming the chemical identity of ED TiO2 film. Figure 1 shows SEM topographies of FTO substrates with and without different BL coatings. As shown in Fig. 1a, bare FTO grains with irregular shapes ranging from tens to hundreds of nanometres in size were observed, leading to a rough surface. For SC BLs, Fig. 1b shows that the FTO grains were overlaid by a film composed of many visually observable nano-pinholes. The thickness of the SC BL on FTO glass is approximately 60 nm and thus the FTO grains are blurred. Figure 1c is an image of the ED BL produced with a current density of 20 μA/cm2 for 500 seconds (denoted as ED-BL-20-500); FTO grains remain visually recognisable, but the sharpness of grain edges is slightly vague, implying that the ED BL film is extremely thin. Magnified images of Fig. 1c are provided in Fig. S2, in which a scale-like ED TiO2 film was grown on the FTO surface with no visually observable defects, indicating a satisfactory surface coverage. It has been reported that the structure of the BL may change because of the internal stress of the deposited film after the annealing process in subsequent scaffold layer preparations27. Consequently the ED-BL-20-500 sample was subjected to annealing at 500 °C for 30 minutes; Fig. 1d shows the resulting SEM image. As shown in Fig. 1d, the coverage of the ED BL remains unchanged and is visually well covered.

Figure S3 shows the cross-sectional view of SEM of ED BL. It revealed that the ED BL is very thin and continuous. However, as mentioned previously, the ED BL is too thin to identify its thickness by SEM. Commercial profile meters cannot be used because the roughness of the FTO is substantially larger than the thickness of the ED BL. We therefore applied SIMS to determine the thickness of the ED BL. Figure 2a is the SIMS depth profile of ED-BL-20-500. The thickness is determined as the signal of secondary tin ion is saturated, which means the ion beam has reached the valley of the FTO surface. From this, the ED BL thickness is estimated to be approximately 29.0 nm, which is approximately half the thickness of the SC BL. The relationship between film thickness and ED time shows that the deposition rate is approximately 0.061 nm/s, as depicted in Fig. 2b.

CV was used to probe the blocking effect of the ED BL because it is an easy and efficient method27. An aqueous Fe(CN)63−/4− solution is typically used as the model redox system in a one-compartment, three-electrode electrochemical cell, in which FTO glass with or without a BL acts as the working electrode. By scanning CV on the working electrode in the aqueous Fe(CN)63−/4− electrolyte, the voltammogram representing the redox reaction between Fe(CN)63− and Fe(CN)64− is interpreted and used as the index of the blocking effect for a BL. Figure 3 shows the CV waves of bare and BL-coated FTO glass. The CV wave of bare FTO glass (black line in Fig. 3a) shows a Nernstian response in which the cathodic peak potential (EPC) and the anodic peak potential (EPA) are separated by 60.90 mV. This peak-to-peak separation (ΔEP) is reasonably deviated from the theoretical value of 56.00 mV for a one-electron reversible reaction because the uncompensated resistances of the solution, wiring and electric contacts were not calculated. This result indicates that the redox reaction of Fe(CN)63−/4− ions is electrochemically reversible on bare FTO glass and thus no blocking effect exists. To further proof this electrochemical reversibility, multiple scan rates were also carried out and shown in Fig. S4. In addition, the peak current density, IP, is given by the Randles-Servcik equation:

where k is a constant, n is the number of electrons transferred in the redox couple, A is the electrode area, D is the diffusion coefficient and ν is the scan rate. The reaction of interest is the cathodic peak in the CV scan and its peak current density is proportional to the electrode area, A, when other parameters in reaction (1) remain unchanged. Because the FTO surface is coated with a BL, the electrode area available for reaction is reduced, leading IP to decrease accordingly. Therefore, the ratio of cathodic IP can be used as an index to express the surface coverage for a BL coating. In the case of an SC BL (red line in Fig. 3a), the ΔEP and IP(BL)/IP(FTO) are 110 mV and 0.795, respectively, indicating a blocking effect of only 20% peak current inhibition. As evidenced by SEM morphology (Fig. 1b), pinholes on the SC BL account for the result. The dependence of the blocking effect and ED BL thickness was evaluated using three ED BL samples prepared with an identical current density of 20 μA/cm2 but at different durations: 250, 500 and 750 seconds, respectively (denoted as ED-BL-20-250, ED-BL-20-500 and ED-BL-20-750, respectively). Shown in Fig. 3b and Table 1, the ΔEP of ED-BL-20-250, ED-BL-20-500 and ED-BL-20-750 are 360.2, 598.4 and 465.4 mV, respectively. This indicates that the redox reaction between Fe(CN)63−/4− ions retards significantly and becomes semi reversible; moreover, the cathodic waves of the ED BL are deformed to a broad peak, implying that the ED BL is densely compact and that the electrons are hopping through the layer instead of having direct contact28,29. The IP(BL)/IP(FTO) of ED-BL-20-500 (blue line) is 0.303, which is lowest among the three ED BLs; 500 seconds therefore appears to be an optimal depositing time in this preliminary study. ED-BL-20-250 (yellow line) may be too thin, allowing electrons to hop easily, rendering an IP(BL)/IP(FTO) of 0.453. The IP(BL)/IP(FTO) of ED-BL-20-750 is 0.451, a higher value than that of ED-BL-20-500; we speculate that because the ED film is sufficiently thick, it undergoes a structural deformation and recombination at the crevice of the thick ED BL. As indirect evidence, the CV peaks of ED-BL-20-750 (green line) appear Nernstian-like rather than sigmoidal with a steady-state current (as shown with ED-BL-20-500), implying the existence of small pinholes or defects in the ED-BL-20-750 sample.

When the ED-BL-20-500 sample was sintered, the CV wave (dotted blue line in Fig. 3c) changed significantly and two sharp, Nernstian-like peaks reappeared. This means structural defects were generated and thus more of the FTO surface area was naked during sintering, rendering an enlarged IP(BL)/IP(FTO) of 0.518, as shown in Table 1. This phenomenon is attributable to volume shrinkage during the crystallisation of TiO2. Since sintering is a necessary step to forming TiO2 scaffolds on FTO glass, it is reasonable to conclude that the ED BL does not currently work under optimal conditions. This warrants further study. Nevertheless, compared with the SC BL, the sintered ED-BL-20-500 significantly outperforms in blocking the charge transfer between Fe(CN)63−/4− ions. Not only the recombination reaction become semi reversible because the ΔEP of the CV wave in ED-BL-20-500 is significantly larger than that in the SC BL but also the surface coverage of the BL on the FTO is improved because the IP(BL)/IP(FTO) of ED-BL-20-500 is 2.62 times smaller than that of the SC BL. Our CV analysis provides a prospective application of ED BLs in PSCs fabricated on a plastic substrate, in which high temperature sintering is prohibited; a room-temperature ED process seems favourable and promising.

The photovoltaic performance of PSCs equipped with different BLs is demonstrated in Fig. 4. Figure 4a shows the IV characteristics of the best performing PSCs and Table 2 summarises their IV parameters. The PSC using an SC BL shows a JSC of 17.11 mA/cm2, VOC of 1015 mV and FF of 0.60, yielding a PCE of 10.42%. The PSC using an ED-BL-20-500 delivers a JSC of 20.01 mA/cm2, VOC of 1000 mV, FF of 0.68 and an improved PCE of 13.60%. Fig. 4b is a statistical chart of IV parameters among six SC-BL-employed PSCs and ten ED-BL-employed PSCs; their averaged IV parameters are listed in Table 2. In both the best performing and average data, PCE improvements for ED BLs are attributable to JSC and FF. The increase in JSC is attributable to a suppressed recombination at the FTO surface, improving charge collection efficiency. The increase in FF is a combined result of thin and compact coatings on the FTO for ED BL, considerably minimising the impact of ohmic resistance.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that ED of TiO2 from an aqueous TiCl3 solution is an efficient method to fabricate ultrathin and compact BLs for PSCs. In this preliminary study, the film thickness growth rate was approximately 0.061 nm/s and the optimal ED condition was 20 μA/cm2 for 500 seconds. Our data revealed that sintering the as-prepared ED BL tended to induce structural defects that could not be examined in SEM but was detectable in CV scans, thereby reducing the blocking effect. Despite this, ED BLs still outperformed commonly used SC BLs in both the blocking effect and series resistance, leading to an improvement of JSC and FF. Future investigations should optimise ED parameters such as the current density, coulomb density and current profile (for instance, pulse current) to understand the relation between film morphology and the blocking effect and to further improve the photovoltaic performance of PSCs.

Methods

Fabrication of TiO2 blocking layer

FTO substrate (2.2 mm, 8 Ω/sq, NSG, Japan) was cleaned by commercial detergent (PK-LCG46, USA) and DI-water in sequence under ultrasonic bath for 20 minutes. TiO2 layer was anodically electrodeposited onto clean FTO substrate, which serves as the working electrode in a three-electrode compartment cell in a bath containing 0.25 M TiCl3 in water (20% in 3% HCl, Alfa Aesar) at room temperature. In this three-electrode system, an Ag/AgCl electrode filled with 3M NaCl solution and a 1 cm2 platinum foil were used as reference electrode and counter electrode, respectively. During entire deposition, the bath was kept at pH 2.5 by Na2CO3 and purged with nitrogen to prevent Ti3+ from oxidation. The experimental factors in this study are current density and depositing time (total passing coulomb density). The as-deposited ED-BL was rinsed by deionized water and dry in air. For comparison, SC-BL was also prepared by spin-coating an ethanol solution containing 0.2 M titanium isopropoxide (TTIP, 97%, Sigma-Aldrich) precursor and 0.2 M HCl 2000 rpm for 30 seconds, followed by a annealing treatment at 500 °C for 30 minutes in air.

Fabrication of perovskite solar cell

Commercial TiO2 paste (30 nm, Dyesol, 30NRT) was diluted with pure ethanol at a ratio of 1/3.5 (w/w) and spin-coated at 4000 rpm for 30 seconds onto afore-prepared BL as mesoporous scaffold, followed by drying at 120 °C for 5 minutes and annealing at 500 °C for 30 minutes in sequence. The resultant film is then immersed into a chemical bath containing 40 mM TiCl4 under 70 °C for 30 minutes and followed by annealing again at 450 °C for 30 minutes. The fabrication of perovskite layer on BL-contained TiO2 scaffold was basically followed by published sequential deposition9. In brief, PbI2 (99.999%, Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) at a concentration of 1 M under stirring at 70 °C. The TiO2 scaffold was infiltrated by PbI2 by spin-coating (6000 rpm for 5 seconds) and followed by drying at 70 °C for 30 minutes. After cooling to room temperature, the substrates were immerged into a solution containing 0.1 M methylamine iodide (MAI, home-made) in 2-propanolfor 50 seconds, then rinsed with 2-propanol, dried by nitrogen flow and baked on 70 °C for 20 minutes. Hole transport material (HTM) was deposited by spin-coating a chlorobenzene solution containing 7.5wt% 2,2′,7,7′- tetrakis(N,N-di-p-methoxyphenylamine) -9,9-spirobifluorene (spiro-OMeTAD, Lumtec, Taiwan) at 3000 rpm for 30 seconds. In order to increase hole mobility of HTM layer, 20 mM bis(trifluoromethane)-sulfonimide lithium salt (Li-TFSI, Sigma-Aldrich) and 120 mM 4-tert- butylpyridine (TBP, 96%, Sigma-Aldrich) were added in above-mentioned spiro-OMeTAD solution. After storing the device at dry atmosphere overnight, a gold electrode was thermally evaporated onto HTM layer as the contact electrode. The entire fabrication process was carried out in a humidity-controlled room.

Characterization and measurement

The topography of BL was scrutinized by FE-SEM (Hitachi SU-8010, Japan). The blocking effect of BL was investigated by CV provided by a computer-controlled potentialstat (Solartron SI 1286, UK) in a three-electrode system with Ag/AgCl reference electrode and 1 cm2 platinum counter electrode, respectively. In CV scan, the aqueous electrolyte containing 0.5 mM potassium hexacyanoferrate(II) trihydrate and 0.5 mM potassium hexacyano- ferrate(III) was utilized with 0.5M KCl as supporting electrolyte. All scan rate of CV measurements were performed at 50mV/s. The I-V characteristic of PSC was measured by a digital source meter (Keithley 2400, USA) under 1 Sun, AM1.5G illumination (Peccell Technologies, PEC-L15, Japan). A KG3 monocrystalline silicon photodiode (Oriel, USA) was used to calibrate the light intensity for better accuracy. A 0.088 cm2 photo-mask was attached to the front side of the PSC to precisely control the illuminating area.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Su, T.-S. et al. Electrodeposited Ultrathin TiO2 Blocking Layers for Efficient Perovskite Solar Cells. Sci. Rep. 5, 16098; doi: 10.1038/srep16098 (2015).

References

Kojima, A., Teshima, K., Shirai, Y. & Miyasaka, T. Organometal halide perovskites as visible-light sensitizers for photovoltaic cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 6050–6051 (2009).

Kim, H.-S. et al. Lead iodide perovskite sensitized all-solid-state submicron thin film mesoscopic solar cell with efficiency exceeding 9%. Sci. Rep. 2, 1–7 (2012).

Lee, M. M., Teuscher, J., Miyasaka, T., Murakami, T. N. & Snaith, H. J. Efficient hybrid solar cells based on meso-superstructured organometal halide perovskites. Science 338, 643–647 (2012).

Liu, M., Johnston, M. B. & Snaith, H. J. Efficient planar heterojunction perovskite solar cells by vapour deposition. Nature 501, 395–398 (2013).

Zhou, H. et al. Interface engineering of highly efficient perovskite solar cells. Science 345, 542–546 (2014).

Wu, Y. et al. Highly compact TiO2 layer for efficient hole-blocking in perovskite solar cells. Appl. Phys. Express 7, 052301 (2014).

Wojciechowski, K., Saliba, M., Leijtens, T., Abate, A. & Snaith, H. J. Sub-150 °C processed meso-superstructured perovskite solar cells with enhanced efficiency. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 1142–1147 (2014).

Jeon, N. J. et al. Solvent engineering for high-performance inorganic–organic hybrid perovskite solar cells. Nat. Mater. 13, 897–903 (2014).

Burschka, J. et al. Sequential deposition as a route to high-performance perovskite-sensitized solar cells. Nature 499, 316–319 (2013).

Im, J.-H., Jang, I.-H., Pellet, N., Grätzel, M. & Park, N.-G. Growth of CH3NH3PbI3 cuboids with controlled size for high-efficiency perovskite solar cells. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 927–932 (2014).

Qin, P. et al. Perovskite solar cells with 12.8% efficiency by using conjugated quinolizino acridine based hole transporting material. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 8516–8519 (2014).

Malinkiewicz, O. et al. Perovskite solar cells employing organic charge-transport layers. Nature Photon. 8, 128–132 (2014).

Ryu, S. et al. Voltage output of efficient perovskite solar cells with high open-circuit voltage and fill factor. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 2614–2618 (2014).

Hong, S. et al. A facile and low-cost fabrication of TiO2 compact layer for efficient perovskite solar cells. Curr. Appl. Phys. 15, 574–579 (2015).

Liu, D. & Kelly, T. L. Perovskite solar cells with a planar heterojunction structure prepared using room-temperature solution processing techniques. Nature Photon. 8, 133–138 (2014).

Hu, Q. et al. Engineering of Electron-Selective Contact for Perovskite Solar Cells with Efficiency Exceeding 15%. ACS Nano 8, 10161–10167 (2014).

Im, J.-H., Lee, C.-R., Lee, J.-W., Park, S.-W. & Park, N.-G. 6.5% efficient perovskite quantum-dot-sensitized solar cell. Nanoscale 3, 4088–4093 (2011).

Noh, J. H., Im, S. H., Heo, J. H., Mandal, T. N. & Seok, S. I. Chemical management for colorful, efficient and stable inorganic–organic hybrid nanostructured solar cells. Nano Lett. 13, 1764–1769 (2013).

Gao, P., Grätzel, M. & Nazeeruddin, M. K. Organohalide lead perovskites for photovoltaic applications. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 2448–2463 (2014).

Ke, W. et al. Perovskite solar cell with an efficient TiO2 compact film. ACS Appl. Mat. Interfaces 6, 15959–15965 (2014).

Yella, A., Heiniger, L.-P., Gao, P., Nazeeruddin, M. K. & Grätzel, M. Nanocrystalline rutile electron extraction layer enables low-temperature solution processed perovskite photovoltaics with 13.7% efficiency. Nano Lett. 14, 2591–2596 (2014).

Moehl, T. et al. Strong photocurrent amplification in perovskite solar cells with a porous TiO2 blocking layer under reverse bias. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 5, 3931–3936 (2014).

Kavan, L., O’Regan, B., Kay, A. & Grätzel, M. Preparation of TiO2 (anatase) films on electrodes by anodic oxidative hydrolysis of TiCl3. J. Electroanal. Chem. 346, 291–307 (1993).

Wu, M.-S., Tsai, C.-H. & Wei, T.-C. Anodic deposition of ultrathin TiO2 film with blocking layer and anchoring layer for dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 159, B80–B85 (2011).

Wu, M.-S., Tsai, C.-H. & Wei, T.-C. Electrochemical formation of transparent nanostructured TiO2 film as an effective bifunctional layer for dye-sensitized solar cells. Chem. Commun. 47, 2871–2873 (2011).

Wu, M.-S. & Lee, R.-H. Electrochemical growth of iron Oxide thin films with nanorods and nanosheets for capacitors. J. Electrochem. Soc. 156, A737–A743 (2009).

Kavan, L., Tétreault, N., Moehl, T. & Grätzel, M . Electrochemical characterization of TiO2 blocking layers for dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 16408–16418 (2014).

Snaith, H. J. & Grätzel, M. The role of a “Schottky Barrier” at an electron‐collection electrode in solid‐state dye‐sensitized solar cells. Adv. Mater. 18, 1910–1914 (2006).

Edri, E., Kedem, N., Cohen, H., Barnes, P. & Hodes, G. Higher open circuit voltage and reduced UV-induced reverse current in zno-based solar cells by a chemically modified blocking layer. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 16884–16891 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST103-2221-E-007-121-MY2) and by a grant from the National Tsing-Hua University (104N2023E1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.C.W. and T.S.S. developed the concept. T.S.S. carried out major experiments including electrodeposition, electrochemical characterizations and device fabrication. T.Y.H. took the microscopic images and C.Y.H. assisted on the raw data processing and repeated the device fabrication. T.C.W. is supervisor of other three authors. T.S.S. and T.Y.H. drafted the article and T.C.W. polished the content to present form. All authors reviewed the paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Su, TS., Hsieh, TY., Hong, CY. et al. Electrodeposited Ultrathin TiO2 Blocking Layers for Efficient Perovskite Solar Cells. Sci Rep 5, 16098 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep16098

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep16098

This article is cited by

-

Self-assembled TiO2 hole-blocking layers for efficient perovskite solar cells

International Journal of Minerals, Metallurgy and Materials (2022)

-

Low-temperature-processed metal oxide electron transport layers for efficient planar perovskite solar cells

Rare Metals (2021)

-

Oblique Electrostatic Inkjet-Deposited TiO2 Electron Transport Layers for Efficient Planar Perovskite Solar Cells

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Silver halide-based composite photocatalysts: an updated account

Rendiconti Lincei. Scienze Fisiche e Naturali (2019)

-

Scalable fabrication of perovskite solar cells

Nature Reviews Materials (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.