Abstract

To date, the proposed mechanisms of nitrogenase-driven photosynthetic H2 production by the diazotrophic unicellular cyanobacterium Cyanothece sp. ATCC 51142 have assumed that reductant and ATP requirements are derived solely from glycogen oxidation and cyclic-electron flow around photosystem I. Through genome-scale transcript and protein profiling, this study presents and tests a new hypothesis on the metabolic relationship between oxygenic photosynthesis and nitrogenase-mediated H2 production in Cyanothece 51142. Our results show that net-positive rates of oxygenic photosynthesis and increased expression of photosystem II reaction centers correspond and are synchronized with nitrogenase expression and H2 production. These findings provide a new and more complete view on the metabolic processes contributing to the energy budget of photosynthetic H2 production and highlight the role of concurrent photocatalytic H2O oxidation as a participating process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Photobiological H2 production is still a nascent technology with long-term potential for sustainable energy production with a low environmental impact. Although direct biophotolytic H2 production has been documented and studied for decades1, significant challenges remain for the development of microbial strains and conditions that can directly and efficiently use sunlight and water to produce H2. Chief among them is the low production rate, which is largely due to feedback inhibition of the H2 producing enzymes by O2, an obligate byproduct of oxygenic photosynthesis. Limitations imposed by O2 sensitivity of the native hydrogenase and nitrogenase enzymes have motivated significant efforts to identify and even engineer O2 tolerant variants2 and multi-stage processes that temporally separate O2 and H2 evolution3. However, to date, the kinetic rates and sustainability of hydrogenase-mediated H2 production are low in comparison to those reported for some diazotrophic organisms that produce H2 in oxic-environments as a byproduct of nitrogenase catalyzed N2 fixation4,5,6.

Nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria have been recognized as one of the most promising photolytic platforms for sustainable H2 production7,8,9,10,11. A unicellular marine strain Cyanothece sp. ATCC 51142 (hereafter Cyanothece 51142) has emerged as a model system because of its ability to produce H2 at rates > 100 μmol-H2 hr−1 mg-Chl−1 under photosynthetic conditions associated with continuous illumination7,12. Although recent genome-enabled studies have provided systems-level insights into the mechanisms governing diurnal growth and metabolism of Cyanothece 511427,13,14,15,16,17, the processes that support H2 production in this organism have yet to be fully resolved. The current and prevailing view assumes that H2 production mediated by energetically expensive nitrogenase activity in Cyanothece 51142 and other closely related strains, is exclusively supported by ATP and reductant derived from oxidation of intracellular glycogen and/or cyclic-electron flow around photosystem (PS) I7,13,18. Here we present evidence to support a new model whereby energy derived directly from oxygenic photosynthesis (i.e., linear electron flow through PS II) is an important process in funding the energy budget required for nitrogenase activity under illuminated, nitrogen-deplete conditions. These conclusions are supported by a combined analysis of detailed process and integrated transcriptome and proteome profiles across a photosynthetically driven H2 production process.

Results

H2 production kinetics

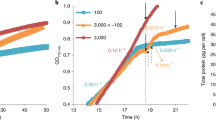

High levels of H2 production were achieved by interrupting medium flow to an ammonium-limited chemostat of Cyanothece 51142, grown in an Ar/CO2 atmosphere under continuous illumination (Fig. 1). The resulting N-depletion yielded metabolically active but non-growing cells, as confirmed by constant cell dry weight (CDW) concentrations (0.086 0.005 gCDW L−1) (Fig. S1). The maximum specific rate of H2 production (qH2) by Cyanothece 51142 was reached after 14.5 hours of N-depletion and measured to be 3.12 mmol-H2 hr−1 g−1CDW (279 μmol-H2 mg-Chl a−1 hr−1) which, to our knowledge, is the highest reported rate of H2 production per unit biomass under photoautotrophic conditions7. H2 production persisted throughout the experiment and is known to be sustainable through this method for more than 100 hours12. The average specific rates were 2.24 and 1.70 mmol-H2 hr−1 g−1CDW over 20 and 40 hours, respectively. Notably, the Cyanothece 51142 cells were maintained under continuous irradiance under all culturing steps; hence, H2 production was not dependent on diel cycling as reported in previous studies7,14.

(A) Specific rates of net H2 and O2 production. Time zero indicates onset of nitrogen-depletion and absence of media addition (dilution rate = 0). (B) Variable chlorophyll fluorescence originating from PS II: the maximum relative electron transfer rate (rETRmax) and the optimal quantum yield (Fv/Fm). Data plotted at times prior to t = 0 represent measurements taken during the ammonia limited chemostat (i.e., steady-state precondition).

Concurrent oxygenic photosynthesis

In this study, H2 production was only measured under aerobic conditions maintained by active oxygenic photosynthesis (i.e., PS II activity) in the bioreactor environment. Dissolved O2 concentrations ranged from steady-state values of 10 μM to 2.4 μM, observed during H2 production. As this specific rate of O2 production (qO2) is non-zero and represents the net rate of photosynthesis, whereby the gross rate of O2 evolution is greater than the rate of respiration19; concurrent observations of O2 and H2 production provide direct evidence of energy acquisition from photocatalytic H2O oxidation via linear electron flow through PS II. Electrons originating from H2O are available for photosynthetic electron transport, which can result in proton reduction and generation of the proton motive force. The qO2 values ranged from 7.5 ± 0.2 mmol-O2 hr−1 g−1CDW to 1.4 mmol-O2 hr−1 g−1CDW for steady-state and N-deplete conditions, respectively (Fig. 1). Net photosynthesis rates decreased immediately upon initiation of N-depletion but then increased inversely with qH2. The capacity for linear electron flow through PS II was also confirmed via measurements of variable Chl a fluorescence (Fig. 1B). The maximum relative rates for electron transport (rETRmax) increased throughout the H2 production profile and at their lowest levels were near the values measured from the steady-state precondition. The optimal photochemical quantum yield of PS II (Fv/Fm) decreased initially with the onset of N-depletion but then increased beyond the steady-state value for the remainder of the H2 production period. Evidence for cyclic electron flow, as inferred from rises in post-illumination Chl a fluorescence (Fig. S2) was only observed during the ammonium-limited chemostat precondition.

Global transcriptional and translational dynamics

Absolute and relative expression of key metabolic processes varied temporally across eight time-resolved sample points within the H2 production profile. Dynamic expression patterns of energy (catabolic and photosynthetic) and nitrogen metabolism genes were observed within the global transcriptome (Fig. 2). The transcriptome was directly compared to and showed general agreement with the global proteome patterns (Fig. S3), which was not entirely unexpected in pre-synchronized, non-growing cells. Enrichment of key functional roles identified correlations between photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation processes (Table S1 and S2): transcripts specific for the main subunits for PS I were enriched (p < 0.004) in a separate group (Fig. 2; blue) and distinct from the main subunits of PS II, which co-clustered (p < 0.05) with the nitrogen fixation machinery (Fig. 2; black).

Hierarchical clustering of the relative mRNA abundances given in reads per kilobase per million reads (RPKM) normalized by steady-state.

3319 unfiltered genes (of 5303) categorized into six main cluster groups: 1-red (181 genes), 2-blue (872 genes; enriched for PS I and electron transport, p < 0.05), 3-yellow (580 genes), 4-magenta (516 genes), 5-green (146 genes) and 6-black (1024 genes; enriched for PS II and N-fixation, p < 0.05).

Nitrogenase and hydrogenase expression

Transcriptional and translational expression patterns of nif genes, as compared to those displayed by the bi-directional hydrogenase (Hox), implicated nitrogenase as the key catalytic process for H2 production in this study. This result is consistent with other studies reporting the physiology of Cyanothece 51142 functioning within N-limited (or deplete) environments7,20. The relative transcript and protein abundance profiles containing all of the nif transcripts, were positively correlated (R2 > 0.71) with the multi-modal (damped oscillatory) pattern of H2 production (Fig. 3C and S4). In general, Nif protein expression corresponded with the transcriptional dynamics and was significantly increased during H2 production (Fig. 4C). The abundances (RPKM) for the encoding transcripts and NifHDK proteins were very high (compared within the global expressome) during chemostat growth as well as throughout H2 production (see supplementary data file). At the same time, the relative abundances of transcripts for the uptake hydrogenase (hupLS) varied during H2 production (Fig. S5), displaying no distinctive patterning with respect to H2 or O2 production. The bidirectional hydrogenase (hox) genes exhibited significantly lower RPKM values than nif (e.g., hoxH was only 0.15% of nifH at max qH2) and the relative abundances did not cluster uniformly or share common profile patterning with H2 production or photosynthesis. Unique peptides were not detected for either the Hup or Hox proteins; hence they were not represented within the global proteome.

Relative abundance profiles of functionally categorized gene transcripts.

Solid black lines indicate the mean profile taken from each collection of genes. Edges of each shaded region represent the respective maximum and minimum relative abundances of transcripts measured at each sampling point. (A) PS I (11 psa genes); (B) PS II (31 psb genes); (C) Nitrogenase (20 nif genes); (D) Glycogen metabolism (8 glg genes); (E) Catabolic energy metabolism (18 genes involved in glycolysis, TCA and oxidative phosphorylation).

Relative abundance profiles of functionally categorized proteins.

Solid black lines indicate the mean profile taken from each collection of proteins. Edges of each shaded region represent the respective maximum and minimum relative abundances of proteins measured at each sampling point. (A) PS I (6 Psa proteins); (B) PS II (15 Psb proteins); (C) Nitrogenase (12 Nif proteins); (D) Glycogen metabolism (7 Glg proteins); (E) Catabolic energy metabolism (13 proteins involved in glycolysis, TCA and oxidative phosphorylation).

Photosynthetic units

The relative abundances of the PS II reaction center transcripts and proteins (PsbA and PsbD) increased with H2 production (Figs 3B and 4B), while relative abundances of PS I reaction centers (PsaA and PsaB) were generally decreased (Figs 3A and 4A). Accordingly, the relative transcript abundances of genes encoding PS II and PS I components displayed positive and negative correlation (R2 > 0.6) with nitrogenase expression, respectively (Fig. S6). Transcript and protein levels of PS II genes correlated with each other and increased with H2 production. In contrast, relative abundance profiles for all PS I transcripts showed multi-modal (oscillatory) patterning (Fig. 3A). The dynamics of PS I proteins differed from the transcripts and displayed mono-modal behavior which was inversely correlated with the net O2 production at ~21 hr (Figs 1 and 4A). Taken together with the net photosynthesis rates and Chl a fluorescence kinetics (Fig. S2), expression dynamics of PS II and PS I machinery provides key evidence linking the H2 production in Cyanothece 51142 with increase in linear electron flow through and concurs with decreased capacity for cyclic electron flow as the dominant ATP generating process.

Energy and glycogen metabolism

The dynamic patterns of key glycogen metabolism pathways were variable and did not correlate with the nitrogenase expression at either the transcriptional or translational levels (Fig. 3D and S6). Evidence for glycogen degradation was observed in the expression profiles of the glycogen debranching enzyme (glgX; cce_3465) and glycogen phosphorylase (glgP, cce_1629), which showed increased abundances relative to the ammonium limited precondition and positive correlation with nitrogenase expression at the translational level (Fig. 4D and S6). However, relative abundance patterns of these glycogen degradation genes were decreased at the transcriptional level. Glycogen syntheses genes revealed opposite expression dynamics as compared to degradation and the relative protein abundance of glycogen synthase (GlgA; cce_3396) was significantly decreased during peak H2 production (Fig. 4D).

The principal processes involved in catabolic energy metabolism, downstream of glycogen degradation, generally showed decreased relative abundances during H2 production and negative correlation with nitrogenase expression (Fig. S6). The relative protein abundance profiles of the two ATP generating steps of glycolysis (phosphoglycerate kinase and pyruvate kinase; cce_4219 and cce_3420, respectively) were significantly decreased (p < 0.05; Fig. 4E). Expression at the transcriptional level (pgk and pyk) was more varied but generally demonstrated a decrease across the H2 production profile (Figs 3E and 4E). The relative transcript and protein abundance profiles for the key reductant generating reactions of the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA), such as isocitrate dehydrogenase (Icd; cce_3202) and succinate dehydrogenase (SdhA; cce_0663), were generally decreased (Figs 3E and 4E); although some variability was observed in the Icd protein profile during the early time points of the H2 production profile. A principal gene in respiration and oxidative phosphorylation for Cyanothece 51142 is cytochrome c oxidase (coxB; cce_1977). The relative abundance profiles of CoxB proteins generally increased with H2 production (Fig. 4E) but showed very weak correlation with nitrogenase expression (Fig. S6). The transcriptional profiles for coxB did not correlate with nitrogenase expression and showed relative decreases during the local net-photosynthesis minima corresponding to peak H2 production (Figs 1 and 3E).

Discussion

The results of this study yield kinetic and genome-scale evidence that supports a new level of insight into the metabolic processes that supply the energy requirements for nitrogenase-mediated H2 production in Cyanothece 51142. These results frame the concept of active reductant and ATP generation originating from a combination of energy metabolism processes including linear electron flow through PS II. The H2 production profiles measured under these experimental conditions correlate positively with nitrogenase and PS II expression but negatively with these of PS I and some of the key catabolic processes required to harvest energy from intercellular glycogen stores. In addition, expression of the principal downstream ATP and reductant generating steps of glycolysis and the TCA cycle were generally decreased relative to the nitrogen limited steady-state precondition. Taken together, these results suggest that the high levels of ATP and reductant required to continuously support nitrogenase catalyzed H2 production do not originate solely from glycogen catabolism but also from linear electron flow through PS II. This is an exciting development, since it has been previously reported and generally assumed that H2 production, via nitrogenase activity in Cyanothece 51142 and highly related strains, is exclusively supported by ATP and reductant derived from glycogen degradation and/or cyclic-electron flow7,13,18,21.

The importance of linear electron flow through PS II, as it relates to supporting nitrogenase driven H2 production in Cyanothece 51142, has been a topic of scientific ambiguity. Multiple studies have investigated the effect of PS II inhibition with 3-(3,4-dichlorphenl)-1,1-dimethylurea (DCMU) during N-depleted H2 production. It has been reported that the addition of DCMU to Ar-flushed Cyanothece 51142 suspensions had no effect on H2 production7. However, another study (that supports the current hypothesis) reported that the addition of DCMU to cells had delayed but dramatic inhibitory effect of H2 production and a similar effect was observed after addition of the electron transport inhibitor p-benzoquinone (BQ), a plastoquinone analog12. The inference from these studies was that cyclic electron flow around PS I was the key mechanism supplying ATP for nitrogenase activity. However, the comprehensive gene and protein profiles presented here show that expression of critical subunits for energy acquisition in PS I (PsaA and PsaB) are decreased compared to the reaction centers of PS II (PsbA and PsbD). Additionally, peak PS II performance, as inferred from variable Chl a fluorecence parameters rETRmax and Fv/Fm, was observed when the relative abundance PS I reaction center proteins were lowest (~20 hr). Hence, reduced expression of PS I did not restrict linear electron flow. This strongly suggests the involvement of PS II in nitrogenase-mediated H2 production. In contrast to prior belief, it is likely that ATP generation is primarily facilitated by linear electron flow through each photosystem accounting for the full potential for proton translocation, ATPase activity and generation of reducing equivalents.

Although changes in expression patterns do not directly represent enzymatic activity, the H2 production and photosynthesis kinetics are in strong agreement with the global transcript and protein measurements. The current results are in agreement with previously reported Chl a fluorescence kinetics, across similar H2 production profiles, which also revealed that the maximum electron transfer rates (ETRmax) increased substantially along the H2 production profiles under different carbon availability regimes12. This evidence complements the in situ reaction measurements that show the gross rate of oxygenic photosynthesis exceeding the rate of respiration which confirms that linear electron flow through PS II is active during nitrogenase mediated H2 production. This result is in contrast to observations made in cyanobacterium Trichodesmium which has been observed to facilitate nitrogen fixation concurrently with oxygenic photosynthesis by scavenging O2 via the PS I mediated Mehler reaction, resulting in negative net-O2 production rates22. We note that results from the current study only represent the physiology and metabolic potential of Cyanothece 51142 under a specific photobioreactor-facilitated H2 production process, which is not directly comparable to any natural cyanobacterial ecosystem.

Nitrogenase-mediated H2 production under aerobic conditions has been observed for Cyanothece 51142 in a number of reported studies7,12. However, previous reports assumed that glycogen acts as the electron donor for oxidative phosphorylation and cyclic-electron flow7. The expression patterns for enzymes required for catabolic energy acquisition within glycolysis (phosphoglycerate kinase and pyruvate kinase) and the TCA cycle (isocitrate dehydrogenase and succinate dehydrogenase) do not support this previously proposed scheme. It is unlikely that glycogen serves as the sole electron donor to nitrogenase while there is a net-positive oxygenic photosynthesis rate; as observed under the conditions reported in this study. Supporting evidence for this realization has previously been presented in a similar study reporting that intracellular carbohydrates levels (glucose equivalents) and glycogen levels are dynamic during H2 production. In fact, the previous report showed evidence for both glycogen synthesis and degradation during the H2 production and demonstrated that the maximum theoretical reductant derived from glycogen oxidation alone could not account for the rate of H2 production measured12.

The current study did not directly investigate nitrogen fixation or diel-regulated cell cycling. Hence, the presented results are not assumed to be ubiquitous and there is no precedent to infer that these extend toward nitrogen fixation in natural ecosystems or N2-replete conditions. Also, it has been proposed that Cyanothece 51142 possesses temporal gene regulation processes which operate as circadian clocks15,16,17,23,24. This study does not refute that concept; in fact, the experiments here avoided external temporal cues by incubating Cyanothece 51142 cells exclusively under constant light through a period of weeks.

In summary, photolytic hydrogen production by autotrophic cyanobacteria represents a promising source of clean, renewable energy. This has been the focus of many fundamental and applied research investments made by both private enterprises and government funding agencies. However, significant developments still need to be made on the basic physiological understanding of these processes before bioprocess optimization may take full effect. This study enables an advance in the field though high resolution multi-omics analyses coupled with detailed kinetics which present a direct relationship between photosynthetic energy acquisition and nitrogenase enzyme activity. These insights bring us closer to resolving the mechanistic underpinnings of energy metabolism used to drive the complex nitrogenase machine for biotechnology that may ultimately enable robust and efficient biophotolytic conversion processes for the production of fuel from H2O, atmospheric CO2 and sunlight.

Methods

Media and culturing conditions

Cyanothece 51142 was cultured in modified ASP-2 medium27, supplemented with 0.75 mM NH4CL, 0.03 mM FeCl3 and 0.75 mM K2HPO4. Photobioreactor (PBR) cultures were operated by a previously described method12. Briefly, di-chromatic (680 and 630 nm LEDs) PBRs were operated as nitrogen limited chemostats with a 5.5 L working volume diluted at a 0.05 hr−1, 30 °C, pH 7.5 and controlled for constant incident and transmitted irradiance (250 and 10 μmol photons m−2 sec−1, respectively). Cells were never exposed to dark conditions during these experiments. The PBR cultures were sparged at 4.08 L min−1 with 1.3% CO2 in argon. H2 production profiles were initiated by arresting flow to the PBR while maintaining sparging with 1.3% CO2 in argon. Steady-state biomass concentrations were measured directly as ash-free cell dry weight (gCDW L−1) as previously reported25.

Transcriptomics

Global RNA sequencing was performed by a previously reported method utilizing SOLiDTM sequencing technology26. RNA was extracted from Cyanothece 51142 cells collected at different time points from the bioreactor using TRIzol® Reagent (Invitrogen), followed by genomic DNA removal and cleaning using RNase-Free DNase kit and Mini RNeasy™ kit (Qiagen). The 50-base short read sequences produced by the 5500XL SOLiDTM sequencer were mapped in color space using SOLiDTM LifeScopeTM software version 2.5 using the default parameters against the genome of Cyanothece sp. ATCC 51142 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome). Resulting BAM files were then analyzed with the Rockhopper program as described previously27 to determine gene expression levels (RPKM).

Proteomics

Global samples were measured via previously reported LC-MS methods28. Briefly, an accurate mass and time (AMT) tag approach was used that utilized tandem mass spectrometry to generate a reference peptide database of observed peptides. Samples were analyzed using an LTQ-Orbitrap VelosTM (Thermo Fisher Scientific) MS interfaced with a reverse phase HPLC system for peptide separation (LC-MS). Only peptides unique in identifying a single protein were used; however, the uniqueness criteria was dropped for analysis of the subset of PS II (PsbA and PsbD) proteins to accommodate for the high degree of similarity between isoforms. Only proteins represented by >2 unique peptides were considered. All AMT values are represented as the mean from duplicate samples.

Clustering and expression profiling

All filtering, clustering and profile analyses were performed with custom scripts (available upon request) written in Matlab and the Bioinformatics Tool Box (Mathworks). The steps used to filter expression profiles are detailed in a supplementary file. Hierarchical clustering was performed on the filtered mRNA data and grouped into six distinguished clusters. Matching protein and mRNA expression profiles synchronized by using K-means clustering to identify six distinct clusters (both protein and mRNA abundances) containing identical genes. The detailed algorithm for synchronized K-means clustering is described in the supplementary file. Eigen-gene and protein profiles are represented as the centroid of all profiles contained in a cluster.

Statistics

Statistical significance (p < 0.05) in the proteomic data sets was determined by the Dunnett Test used to compare expression to the steady-state preconditions. Enrichment, within the transcriptomic and proteomic data sets, is defined as the percentage of genes within the profile for which a function has been assigned being significantly higher than the percentage of genes of the same function in the entire genome with a p-value of <0.05 according to Fisher’s exact test.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Bernstein, H. C. et al. Multi-Omic Dynamics Associate Oxygenic Photosynthesis with Nitrogenase-Mediated H2 Production in Cyanothece sp. ATCC 51142. Sci. Rep. 5, 16004; doi: 10.1038/srep16004 (2015).

References

Gaffron, H. & Rubin, J. Fermentative and photochemical production of hydrogen in algae. J. Gen. Physiol. 26, 219–240 (1942).

Ghirardi, M. L., Togasaki, R. K. & Seibert, M. in Biotechnology for Fuels and Chemicals 141–151 (Springer, 1997).

Melis, A., Zhang, L., Forestier, M., Ghirardi, M. L. & Seibert, M. Sustained photobiological hydrogen gas production upon reversible inactivation of oxygen evolution in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant. Physiol. 122, 127–136 (2000).

Levin, D. B., Pitt, L. & Love, M. Biohydrogen production: prospects and limitations to practical application. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energ. 29, 173–185 (2004).

Reddy, K., Haskell, J. B., Sherman, D. & Sherman, L. Unicellular, aerobic nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria of the genus Cyanothece. J. Bacteriol. 175, 1284–1292 (1993).

Tsygankov, A., Fedorov, A., Kosourov, S. & Rao, K. Hydrogen production by cyanobacteria in an automated outdoor photobioreactor under aerobic conditions. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 80, 777–783 (2002).

Bandyopadhyay, A., Stöckel, J., Min, H., Sherman, L. A. & Pakrasi, H. B. High rates of photobiological H2 production by a cyanobacterium under aerobic conditions. Nat. Comm. 1, 139 (2010).

Bothe, H. & Newton, W. E. in Microbial BioEnergy: Hydrogen Production 137–153 (Springer, 2014).

Kosourov, S. et al. Hydrogen photoproduction by immobilized N2-fixing cyanobacteria: understanding the role of the uptake hydrogenase in the long-term process. Appl. Enviro. Microbiol. 80, 5807–5817 (2014).

Masukawa, H., Sakurai, H., Hausinger, R. P. & Inoue, K. Sustained photobiological hydrogen production in the presence of N 2 by nitrogenase mutants of the heterocyst-forming cyanobacterium Anabaena. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energ. 39, 19444–19451 (2014).

Park, J.-W., Nam, S. W., Kim, H. S., Youn, S.-H. & Yih, W. Enhanced photobiological H2 production by the addition of carbon monoxide and hydrogen cyanide in two unicellular N2-fixing cyanobacterial strains isolated from Korean coasts. Ocean. Sci. J. 49, 11–18 (2014).

Melnicki, M. R. et al. Sustained H2 production driven by photosynthetic water splitting in a unicellular cyanobacterium. MBio 3, e00197–00112 (2012).

Aryal, U. K. et al. Proteome analyses of strains ATCC 51142 and PCC 7822 of the diazotrophic cyanobacterium Cyanothece sp. under culture conditions resulting in enhanced H2 production. Appl. Enviro. Microbiol. 79, 1070–1077 (2013).

Bandyopadhyay, A., Elvitigala, T., Liberton, M. & Pakrasi, H. B. Variations in the rhythms of respiration and nitrogen fixation in members of the unicellular diazotrophic cyanobacterial genus Cyanothece. Plant. Physiol. 161, 1334–1346 (2013).

Colon-Lopez, M. S., Sherman, D. M. & Sherman, L. A. Transcriptional and translational regulation of nitrogenase in light-dark-and continuous-light-grown cultures of the unicellular cyanobacterium Cyanothece sp. strain ATCC 51142. J. Bacteriol. 179, 4319–4327 (1997).

Colón-López, M. S. & Sherman, L. A. Transcriptional and translational regulation of photosystem I and II genes in light-dark-and continuous-light-grown cultures of the unicellular cyanobacterium Cyanothece sp. strain ATCC 51142. J. Bacteriol. 180, 519–526 (1998).

Welsh, E. A. et al. The genome of Cyanothece 51142, a unicellular diazotrophic cyanobacterium important in the marine nitrogen cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105, 15094–15099 (2008).

Skizim, N. J., Ananyev, G. M., Krishnan, A. & Dismukes, G. C. Metabolic pathways for photobiological hydrogen production by nitrogenase-and hydrogenase-containing unicellular cyanobacteria Cyanothece. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 2777–2786 (2012).

Bernstein, H. C. et al. Direct measurement and characterization of active photosynthesis zones inside wastewater remediating and biofuel producing microalgal biofilms. Bioresource. Technol. 156, 206–215 (2014).

Vu, T. T. et al. Genome-scale modeling of light-driven reductant partitioning and carbon fluxes in diazotrophic unicellular cyanobacterium Cyanothece sp. ATCC 51142. PLoS Comput. Biol. (2012).

Min, H. & Sherman, L. A. Hydrogen production by the unicellular, diazotrophic cyanobacterium Cyanothece sp. strain ATCC 51142 under conditions of continuous light. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 4293–4301 (2010).

Berman-Frank, I. et al. Segregation of nitrogen fixation and oxygenic photosynthesis in the marine cyanobacterium Trichodesmium. Science 294, 1534–1537 (2001).

Červený, J. & Nedbal, L. Metabolic rhythms of the cyanobacterium Cyanothece sp. ATCC 51142 correlate with modeled dynamics of circadian clock. J. Biol. Rhythm. 24, 295–303 (2009).

Schneegurt, M. A., Sherman, D. M., Nayar, S. & Sherman, L. A. Oscillating behavior of carbohydrate granule formation and dinitrogen fixation in the cyanobacterium Cyanothece sp. strain ATCC 51142. J. Bacteriol. 176, 1586–1597 (1994).

Pinchuk, G. E. et al. Constraint-based model of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 metabolism: a tool for data analysis and hypothesis generation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 6, e1000822 (2010).

Beliaev, A. S. et al. Inference of interactions in cyanobacterial–heterotrophic co-cultures via transcriptome sequencing. ISME J. (2014).

McClure, R. et al. Computational analysis of bacterial RNA-Seq data. Nucleic. Acids Res. 41, e140–e140 (2013).

Sadler, N. C. et al. Live cell chemical profiling of temporal redox dynamics in a photoautotrophic cyanobacterium. ACS Chem. Biol. 9, 291–300 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Allan Konopka, Jim Fredrickson, Lindsey Anderson and Bobbi-Jo Webb-Robertson for helpful discussions and technical assistance. Author HCB is grateful for support given by the Linus Pauling Distinguished Postdoctoral Fellowship, a Laboratory Directed Research and Development Program of PNNL. This research was supported by the Genomic Science Program (GSP), Office of Biological and Environmental Research (BER), U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and is a contribution of the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) Biofuels Scientific Focus Area (BSFA). The genome annotation efforts used customized processes and resources developed and supported by the Foundational Scientific Focus Area at PNNL. MS-based proteomic measurements used capabilities developed partially under the GSP Panomics project. A significant portion of the research was performed using the Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory (EMSL), a national scientific user facility sponsored by DOE BER and located at PNNL. PNNL is operated for the DOE by Battelle Memorial Institute under Contract DE-AC05-76RLO 1830.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ASB designed the experiment. M.A.C., E.A.H., N.C.S., M.R.M., L.M.M., C.D.N. and H.C.B. performed the experiment. M.F.B., R.S.M., N.C.S., A.T.W. and H.C.B. analyzed the data. H.C.B., A.S.B. and R.S.M. interpreted the data and wrote the paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Bernstein, H., Charania, M., McClure, R. et al. Multi-Omic Dynamics Associate Oxygenic Photosynthesis with Nitrogenase-Mediated H2 Production in Cyanothece sp. ATCC 51142. Sci Rep 5, 16004 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep16004

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep16004

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.