Abstract

Linear plus linear homologous recombination-mediated recombineering (LLHR) is ideal for obtaining natural product biosynthetic gene clusters from pre-digested bacterial genomic DNA in one or two steps of recombineering. The natural product salinomycin has a potent and selective activity against cancer stem cells and is therefore a potential anti-cancer drug. Herein, we separately isolated three fragments of the salinomycin gene cluster (salO-orf18) from Streptomyces albus (S. albus) DSM41398 using LLHR and assembled them into intact gene cluster (106 kb) by Red/ET and expressed it in the heterologous host Streptomyces coelicolor (S. coelicolor) A3(2). We are the first to report a large genomic region from a Gram-positive strain has been cloned using LLHR. The successful reconstitution and heterologous expression of the salinomycin gene cluster offer an attractive system for studying the function of the individual genes and identifying novel and potential analogues of complex natural products in the recipient strain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

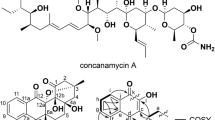

Red/ET recombineering in E. coli1,2, is a powerful technique for the genetic engineering of natural product biosynthetic pathways, especially for large polyketide synthetase (PKS) as well as nonribosomal peptide-synthetase (NRPS)3,4,5,6. Recently, this technique was used to clone large biosynthetic gene clusters from a complex DNA source into a vector by linear plus linear homologous recombination (LLHR)7. LLHR is mediated by the full-length Rac prophage protein RecE, an exonuclease, its partner RecT, a single-strand DNA-binding protein and Redγ, an inhibitor of the major exonuclease. RecA, a repair protein, is also included8. Fu et al., 2012 cloned ten hidden biosynthetic pathways from digested genomic DNA of Gram-negative P. luminescens using LLHR and two of these have been successfully expressed in E. coli7,9. Many gene clusters have also been cloned by this method, including the syringolin, glidobactin and colibactin gene clusters10,11,12 and all are from Gram-negative strains.

An emerging idea in cancer biology is that tumors harbor a group of cells, known as cancer stem cells (CSCs), which have the unique ability to regenerate cancers13,14. In addition to promoting tumor growth, growing evidence indicates that CSCs may be responsible for cancer recurrence, resistance to conventional treatments and metastasis15,16,17,18. Recently, Lander et al., 2009 showed that salinomycin can selectively kill breast CSCs after screening 16,000 compounds19. Further studies revealed that salinomycin has potent and selective activity against other cancer cell lines20,21. In vitro data revealed that salinomycin pre-treatment reduced the tumor-seeding ability of cancer cell lines greater than 100-fold over the chemotherapy drug paclitaxel. Furhtermore, salinomycin reduced mammary tumor size in mice to a greater extent than paclitaxel19.

Salinomycin is produced by Streptomyces albus22 and has been used to prevent Coccidioidomycosis in poultry and alter gut flora to improve nutrient absorption in ruminants23. The compound interferes with potassium transport across mitochondrial membranes, thus reducing intracellular energy production. It may also disrupt Na+/Ca2+ exchange in skeletal and, in some cases, cardiac muscle, allowing a fatal accumulation of intracellular calcium24.

Earlier results revealed that the polyketide chain of salinomycin is synthesized by an assembly line of nine PKS multienzymes (salAI–IX). The nine PKS genes are collinearly arranged in the cluster. Four of these multienzymes (salAIV, salAVI, salAVII and salAIX) each catalyze a single extension module, while the other five (salAI, salAII, salAIII, salAV and salAVIII) encode two extension modules. In addition to the nine PKS genes, some other genes play vital roles in salinomycin biosynthesis25,26. Upstream of the PKS genes, the adjacent orf1, orf2 and orf3 do not belong to the salinomycin cluster, but salN and salO encode putative regulatory proteins. SalP and SalQ are involved in the formation of the butyrate extender unit for salinomycin biosynthesis and inactivation of salP and salQ reduced the yields of salinomycin by 10% and 36%, respectively when compared to wild-type26. Downstream of the PKS genes, orf18 is predicted to encode a peptidyl carrier protein and targeted inactivation of orf18 results in a 50–60% reduction in salinomycin production compared to wild-type25.

Herein, we report the cloning of the 106-kb salinomycin gene cluster (salO-orf18) from the genomic DNA of Streptomyces albus DSM41398 by three rounds of direct cloning followed by assembling. All of the genes are oriented in the same direction and under the original promoters. The gene cluster was introduced into S. coelicolor A3(2) for successful heterologous production of salinomycin.

Results

Constructing a BAC vector for direct cloning of the salinomycin gene cluster by quadruple recombineering

In order to construct a vector for direct cloning of the salinomycin gene cluster, the four fragments (backbone of pBeloBAC11, amp-ccdB, salO and orf18) each had a 50-bp overlapping sequence, as illustrated in Fig. 1 and were co-electroporated into GB05dir-gyrA4625, a CcdB-resistant E. coli strain containing the mutation GyrA R462M27,28 and LLHR-proficient recombinase (RecET, Redγ and RecA), to form the BAC vector by quadruple recombineering.

The BAC vector contained a homology arm to salO (292 bp) and orf18 (238 bp) and a cassette of the counterselection marker CcdB, which can be used to delete the background from the original BAC vector for direct cloning. A CcdB function test was performed as described previously5.

Direct cloning of the salinomycin gene cluster

As mentioned above, salO encodes putative regulatory protein and orf18 is an essential factor for salinomycin production. Additionally, the restriction site (EcoRV), which can be utilized for direct cloning, is located in salO and orf18. Thus, we attempted to directly clone the 106-kb fragment (salO-orf18) using one and two-step recombination reactions7 with the BAC vector but were unsuccessful.

Hence, we divided the gene cluster into three fragments for direct cloning (Fig. 2a). We directly cloned the fragments of salO-salAIV (F1) and salAIX-orf18 (F3) using one step of LLHR7 with an efficiency of 4/24 and 1/24, respectively (Fig. S1a,c). We directly cloned the fragment of salAIV-salAVIII (F2) by a two-step recombination with an efficiency of 8/24 (Fig. S1b). Due to the repeated sequence in salAIV-salAVIII (Fig. S2), we were unable to directly clone this fragment by one step of LLHR. Therefore, this fragment was isolated using a neomycin selection marker flanked by lox71-lox66, which could be utilized to delete the selection marker conveniently in the assembling procedure. The three desired fragments were inserted in plasmids p15A-amp-F1, p15A-amp-F2-lox71-neo-lox66 and p15A-amp-F3, respectively.

Diagram of direct cloning and assembling of the salinomycin gene cluster and engineering for conjugation and integration.

(a) Genomic DNA was digested by restriction enzymes to produced three fragments, which were recombined with p15A-amp after direct cloning. Fragment F2 was isolated using the neomycin selection marker. (b) Three fragments were assembled. Fragments F2 and F3 were assembled by a ligation reaction. F1 and F2&3 were assembled together by triple recombineering to produce pBeloBAC11-sal-lox71-neo-lox66. (c) The neomycin selection marker was deleted by Cre from the pBeloBAC11-sal-lox71-neo-lox66 plasmid and the integrase-attP-oriT-apramycin cassette was inserted into the noncoding sequence to generate the final construct, pBeloBAC-sal-int-attP-oriT-apr. hyg, hygromycin resistance gene; amp, ampicillin resistance gene; neo, neomycin resistance gene.

Assembling of the salinomycin gene cluster and engineering for conjugation and integration

Figure 2b show the assembling procedure to reconstitute the entire cluster. F2 and F3 were ligated using the original restriction site of AsiSI/EcoRV in the gene cluster, which did not cause any open reading frame shift. The neomycin selection marker was deleted by Cre from the plasmid p15A-amp-F2-lox71-neo-lox66 to produce p15A-amp-F2. Modifications were made to p15A-amp-F3 with two steps of recombineering. The neomycin selection marker flanked by lox71-lox66 was inserted into the non-coding sequence of F3 in the first recombineering step. The second recombineering step replaced the ampicillin selection marker with the hyg-ccdB cassette to produce p15A-hyg-ccdB-F3-lox71-neo-lox66. F3 was excised by AsiSI/EcoRV and inserted into the AsiSI/EcoRV site in p15A-amp-F2 by ligation to produce p15A-amp-F2&3-lox71-neo-lox66.

The ampicillin selection marker of the previous ligation product was replaced by the hyg-ccdB cassette to produce the plasmid p15A-hyg-ccdB-F2&3-lox71-neo-lox66. The plasmid p15A-amp-F1 was digested by EcoRV to release the fragment F1 and p15A-hyg-ccdB-F2&3-lox71-neo-lox66 was digested by EcoRV/MseI to excise F2&3-lox71-neo-lox66. The two fragments overlapped by 592 bp and each fragment had a homologous arm with previously constructed BAC vector. The BAC vector was transformed into GB05 cells harboring the plasmid pSC101-ccdA-gbaA. As CcdB is toxic, we induced CcdA, that inactivates the CcdB toxin, by rhamnose in the liquid medium or culture plates. The two previous linearize fragments were co-transformed into GB05 cells containing the BAC vector and the expression plasmid (pSC101-ccdA-gbaA) to produce pBeloBAC11-sal-lox71-neo-lox66. We verified pBeloBAC11-sal-lox71-neo-lox66 using three restriction enzymes, the results (Fig. S3) showed that the pBeloBAC11-sal-lox71-neo-lox66 was correct.

To introduce the gene cluster into a heterologous expression host, few necessary elements were engineered before conjugation. The two step engineering procedure for conjugation and integration is diagrammed in Fig. 2c. Finally, the gene cluster was introduced into S. coelicolor A3(2) by conjugation and integrated into its chromosome.

Heterologous production of salinomycin in S. coelicolor A3(2)

The genetic organization and promoters of the obtained salinomycin gene cluster are identical to those of the original producer S. albus DSM41398. After conjugation, the exconjugant colonies were confirmed by PCR and subsequently analyzed for heterologous salinomycin production. The salinomycin gene cluster was successfully inserted into the attB site of S. coelicolor A3(2) (Fig. S4).

The metabolite profiles of the wild-type S. coelicolor and the mutant strains S. coelicolor::sal were analyzed by HPLC-MS and compared with the salinomycin standard (Fig. 3a (Ref)). Thus, we were able to identify Salinomycin in extracts of the mutant strains S. coelicolor::sal via HPLC-MS (Fig. 3a,b) and heterologous expression could be unambiguously confirmed by comparing MS2 fragmentation pattern (Fig. 3c).

Heterologous salinomycin production.

(a) HPLC-MS analysis (base peak chromatograms (BPC) m/z 200–2000+ All MS) of the salinomycin standard (Ref), the wild-type S. coelicolor A3(2) and mutant S. coelicolor::sal. Salinomycin is indicated by an asterisk. (b) MS2 fragmentation patterns of precursor m/z 733.5 [M–H2O+H]+ in standard salinomycin and in S. coelicolor::sal mutant.

Discussion

Over the past several decades, numerous multifunctional megasynthases have been identified, cloned, sequenced, engineered and heterologously expressed in suitable hosts. Traditionally, natural product biosynthetic gene clusters were retrieved from a single cosmid or reconstructed from several cosmids within a genomic library of the natural producer stain, which was time consuming due to subsequent cloning steps following the screening process from a genomic library4,29.

LLHR-mediated recombineering was ideal for direct cloning of the salinomycin gene cluster from pre-digested genomic DNA after one or two steps of recombineering7. Red/ET recombineering has traditionally been applied for heterologous expression of biosynthetic pathways to modify the biosynthetic pathways30.

The failure to directly clone the 106-kb fragment with the BAC vector may have resulted from several considerations. First, the recombineering efficiency is very low for large fragments. Although the developed method of direct cloning is efficient for cloning up to ~52-kb fragments from a bacterial genome7, it is limited by inefficient co-transformation of two linear molecules, especially for long fragments (106 kb). Moreover, the gene cluster contains GC-rich sequences. We studied the impact of the GC content on the recombineering efficiency and found that it was decreased for sequences with high GC content (data not shown). Second, enrichment of the target DNA is difficult after extracting the genomic DNA. Genomic DNA is susceptible to shearing forces associated with mechanical destruction and degradation by nuclease activity. Therefore, it is difficult to obtain the intact salinomycin biosynthesis gene cluster, especially for S. albus DSM 41398, the gram-positive strain. Third, previous data revealed that the Redβ monomer anneals ~11 bp of DNA and the smallest stable annealing intermediate requires only 20 bp of DNA and two Redβ monomers31. In this study, we found that most of the colonies resulted from self-circularization of the vector used for direct cloning after recombineering although there were no obvious homologous regions in the backbone of the vector. As a result, it is difficult to screen the correct clone from thousands of self-circularized vectors.

In parallel to our LLHR-mediated direct cloning, the other DNA cloning methods for bioprospecting have their distinct merits. LLHR-mediated RecET direct cloning was not accessible to metagenomic DNA. Bioprospecting of metagenomics needs DNA synthesis and assembly method. Streptomyces phage ϕBT1 integrase-mediated in vitro site-specific recombination could assembly the 56 kb epothilone biosynthetic gene cluster using modules as units. The authors didn’t prove that the complete gene cluster with att site scars could be expressed in a heterologous host32. The incorrect linker between modules might affect the biosynthesis33. An intact DNA sequence can be obtained by the Gibson assembly34,35, which is the most efficient ‘chew back and anneal’ method36,37,38. The Gibson assembly was also proved to be capable of direct cloning of a 41 kb conglobatin biosynthetic gene cluster39. Much larger DNA fragment can be directly cloned by transformation-associated recombination (TAR) in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae40,41. However unregulated yeast homologous recombinase might cause rearrangement of repetitive PKS/NRPS biosynthetic DNA sequences. The oriT-directed cloning for Gram-negative bacteria relies on available genetic tools to insert conjugation elements on the genome by two elaborated vectors. Although it is not straight forward, it has a capacity of cloning regions up to 140 kb from the genome of Burkholderia pseudomallei42. The phage ϕBT1 integrase-mediated direct cloning was developed for Gram-positive bacteria Streptomyces. It has the similar logic to oriT-directed cloning, which starts with integration of a capture vector by genome engineering at two spots, but both excision and circularization happen in the original bacteria43. If Bacillus subtilis is justified as a suitable heterologous host for a biosynthetic gene cluster, its genome can be used as a vector for direct cloning of giant DNA, which has the potential to overcome the capacity limit of the BAC vector44.

Compare to above methods our LLHR-mediated direct cloning has a significant feature. It is a genetic tool in E coli, which is simple, convenient and cost-effective. The important improvement in this study is to combine RecET mediated direct cloning and lambda Red mediated plasmids stitching to hierarchically clone the intact 106kb salinomycin gene cluster. The reliability of the cloning method has been proved by subsequently successful heterologous expression in S. coelicolor A3(2). Our results represent a potent approach to mine the function of the individual genes and identify novel and potentially useful analogues of the complex natural products through module exchange in the recipient.

Methods

Strains, plasmids and culture conditions

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are shown in Table S1. All primers were synthesized by Sigma-Genosys (Germany) (Table S2). All restriction enzymes, Taq polymerase and DNA markers were purchased from New England Biolabs (UK).

E. coli cells were cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) liquid media or on LB agar (1.2% agar). Ampicillin (amp, 100 μg mL−1), kanamycin (km, 15 μg mL−1), chloramphenicol (cm, 15 μg mL), hygromycin (hyg, 30 μg mL−1), apramycin (apr, 15 μg mL−1) and tetracycline (tet, 5 μg mL−1) were added to the media as required.

For sporulation and conjugation, S. coelicolor A3(2) was grown on mannitol salt (MS) agar plates for 10 days. If necessary for conjugation, apr (50 μg mL−1) and nalidixic acid (NA, 50 μg mL−1) were added.

S. albus DSM41398, S. coelicolor A3(2) and mutant strains were cultivated in M1 medium (10 g L−1 starch, 4 g L−1 yeast extract, 2 g L−1 peptone) at 30 °C with constant agitation at 180 rpm.

Bacterial genomic DNA isolation

S. albus DSM41398 was cultured in 30 mL medium (4 g L−1 glucose, 4 g L−1 yeast extract, 10 g L−1 malt extract, pH 7.2) at 30 °C for two days. After centrifugation, the cells were resuspended in 5 mL SET buffer (75 mM NaCl, 25 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5). After adding lysozyme to a final concentration of 1 mg mL−1 and incubating at 37 °C for 0.5–1 h, 500 μL 10% SDS and 125 μL 20 mg mL−1 proteinase K were added and the mixture was incubated at 55 °C with occasional inversion for 2 h until the solution became clear. The solution was combined with 2 mL 5 M NaCl and 8 mL phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) and incubated at room temperature for 0.5 h with frequent inversion. After centrifuging at 4500 × g for 15 min, the aqueous phase was transferred to a new tube using a blunt-ended pipette tip and the DNA was precipitated by adding one volume of isopropanol and gently inverting the tube. DNA was transferred to a microfuge tube, rinsed with 75% ethanol, dried under vacuum and dissolved in ddH2O.

Preparation of electrocompetent cells for recombineering

Recombineering and direct cloning were performed as described previously7 with several small modifications. The linear cloning vector p15A-amp, flanked with homology arms to target genes, was amplified by PCR using p15A-amp-ccdB5 as a template. Digested genomic DNA (10 μg) was mixed with 2 μg linear cloning vector and co-transformed into competent cells by electroporation.

Conjugation

Conjugation between E. coli and S. coelicolor A3(2) was performed as described previously with minor modifications45. The plasmid containing the salinomycin gene cluster and elements for conjugation and integration was transformed into the donor strain E. coli ET12567 (pUZ8002). The donor strain was prepared by growth overnight at 37 °C in LB supplemented with antibiotics. The overnight culture was diluted 100-fold in 15 mL fresh LB plus antibiotic and grown at 30 °C to an OD600 of 0.3. The E. coli cells were washed twice with an equal volume of LB and resuspended in 0.1 volume LB. S. coelicolor A3(2) mycelia fragments were harvested from a four-day-old culture in TSB medium and served as the recipient strain. The donor strain and recipient strain were mixed with equal volumes, the mixture was centrifuged and the supernatant was discarded. Finally, the pellet was resuspended in the residual liquid. The mating mixture was spread on MS plates and incubated at 30 °C. After 24 h, the cells were collected and spread on MS plates with NA (50 μg mL−1) and apr (50 μg mL−1) and further incubated at 30 °C until exconjugant colonies appeared.

Extraction and analysis of the compound

S. coelicolor::sal gene cluster cells were cultivated in 300-mL flasks containing 30 mL M1 medium supplemented with apr (25 μg mL−1). The culture was grown at 30 °C with constant agitation at 180 rpm. After 13 days, the biomass was harvested by centrifugation and 2% resin Amberlite XAD-16 was added to the supernatant before the resin was extracted with methanol. The received extracts were evaporated and dissolved in methanol and used for HPLC-MS analysis. The HPLC-MS measurement was performed on a Dionex Ultimate 3000 LC system utilizing a Waters Acquity BEHC-18 column (50 × 2 mm, 1.7-μm particle size). Separation of 2 μL sample was obtained using a linear gradient of A (water and 0.1% formic acid) and B (acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid) at a flow rate of 600 μL min−1 at 45 °C. The gradient was initiated by a 0.5-min isocratic step at 5% B followed by an increase to 95% B over 9 min and a final 1.5-min step at 95% B before reequilibration with initial conditions. UV spectra were recorded by a DAD from 200–600 nm. MS measurement was carried on an amaZon speed mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) using the standard ESI source. Mass spectra were acquired in centroid mode ranging from 200–2000 m/z in positive ionization mode with auto MS2 fragmentation.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Yin, J. et al. Direct cloning and heterologous expression of the salinomycin biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptomyces albus DSM41398 in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Sci. Rep. 5, 15081; doi: 10.1038/srep15081 (2015).

References

Zhang, Y., Buchholz, F., Muyrers, J. P. P. & Stewart, A. F. A new logic for DNA engineering using recombination in Escherichia coli. Nat. Genet. 20, 123–128 (1998).

Zhang, Y., Muyrers, J. P. P., Testa, G. & Stewart, A. F. DNA cloning by homologous recombination in Escherichia coli. Nat. Biotechnol. 18, 1314–1317 (2000).

Gross, F. et al. Metabolic engineering of Pseudomonas putida for methylmalonyl-CoA biosynthesis to enable complex heterologous secondary metabolite formation. Chem. Biol. 13, 1253–1264 (2006).

Fu, J. et al. Efficient transfer of two large secondary metabolite pathway gene clusters into heterologous hosts by transposition. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, e113 (2008).

Wang, H. et al. Improved seamless mutagenesis by recombineering using ccdB for counterselection. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, e37 (2014).

Wenzel, S. C. et al. Heterologous Expression of a Myxobacterial Natural Products Assembly Line in Pseudomonads via Red/ET Recombineering. Chem. Biol. 12, 349–356 (2005).

Fu, J. et al. Full-length RecE enhances linear-linear homologous recombination and facilitates direct cloning for bioprospecting. Nat. Biotechnol. 30, 440–446 (2012).

Wang, J. et al. An improved recombineering approach by adding RecA to lambda Red recombination. Mol. Biotechnol. 32, 43–53 (2006).

Bian, X., Plaza, A., Zhang, Y. & Müller, R. Luminmycins A–C, Cryptic Natural Products from Photorhabdus luminescens Identified by Heterologous Expression in Escherichia coli. J. Nat. Prod. 75, 1652–1655 (2012).

Bian, X. et al. Heterologous Production of Glidobactins/Luminmycins in Escherichia coli Nissle Containing the Glidobactin Biosynthetic Gene Cluster from Burkholderia DSM7029. Chembiochem 15, 2221–2224 (2014).

Bian, X. et al. Direct cloning, genetic engineering and heterologous expression of the syringolin biosynthetic gene cluster in E. coli through Red/ET recombineering. Chembiochem 13, 1946–1952 (2012).

Bian, X. et al. In Vivo Evidence for a Prodrug Activation Mechanism during Colibactin Maturation. Chembiochem 14, 1194–1197 (2013).

Reya, T., Morrison, S. J., Clarke, M. F. & Weissman, I. L. Stem cells, cancer and cancer stem cells. Nature 414, 105–111 (2001).

Al-Hajj, M., Wicha, M. S., Benito-Hernandez, A., Morrison, S. J. & Clarke, M. F. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 100, 3983–3988 (2003).

Noirot, P. & Kolodner, R. D. DNA Strand Invasion Promoted by Escherichia coli RecT Protein. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 12274–12280 (1998).

Dean, M., Fojo, T. & Bates, S. Tumour stem cells and drug resistance. Nat. Rev. Cancer 5, 275–284 (2005).

McIntosh, J. A., Donia, M. S. & Schmidt, E. W. Ribosomal peptide natural products: bridging the ribosomal and nonribosomal worlds. Nat. Prod. Rep. 26, 537–559 (2009).

Lobo, N. A., Shimono, Y., Qian, D. & Clarke, M. F. The biology of cancer stem cells. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 23, 675–699 (2007).

Gupta, P. B. et al. Identification of selective inhibitors of cancer stem cells by high-throughput screening. Cell 138, 645–659 (2009).

Kim, J.-H. et al. Salinomycin sensitizes cancer cells to the effects of doxorubicin and etoposide treatment by increasing DNA damage and reducing p21 protein. Br. J. Pharmacol. 162, 773–784 (2011).

Lu, D. et al. Salinomycin inhibits Wnt signaling and selectively induces apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 108, 13253–13257 (2011).

Mitani, M., Yamanishi, T. & Miyazaki, Y. Salinomycin: A new monovalent cation ionophore. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 66, 1231–1236 (1975).

Miyazaki, Y. et al. Salinomycin, a new polyether antibiotic. J. Antibiot. 27, 814–821 ( 1974).

Story, P. & Doube, A. A case of human poisoning by salinomycin, an agricultural antibiotic. New Zeal. Med. J. 117, U799 (2004).

Jiang, C., Wang, H., Kang, Q., Liu, J. & Baia, L. Cloning and characterization of the polyether salinomycin biosynthesis gene cluster of Streptomyces albus XM211. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 994–1003 (2012).

Yurkovich, M. E. et al. A Late-Stage Intermediate in Salinomycin Biosynthesis Is Revealed by Specific Mutation in the Biosynthetic Gene Cluster. Chembiochem 13, 66–71 (2012).

Bernard, P. Positive selection of recombinant DNA by CcdB. Biotechniques 21, 320–323 (1996).

Bernard, P. & Couturier, M. Cell killing by the F plasmid CcdB protein involves poisoning of DNA-topoisomerase II complexes. J. Mol. Biol. 226, 735–745 (1992).

Ongley, S. E. et al. High-Titer Heterologous Production in E. coli of Lyngbyatoxin, a Protein Kinase C Activator from an Uncultured Marine Cyanobacterium. ACS Chem. Biol. 8, 1888–1893 (2013).

Kolinko, I. et al. Biosynthesis of magnetic nanostructures in a foreign organism by transfer of bacterial magnetosome gene clusters. Nat.Nano. 9, 193–197 (2014).

Erler, A. et al. Conformational adaptability of Redβ during DNA annealing and implications for its structural relationship with Rad52. J. Mol. Biol. 391, 586–598 (2009).

Zhang, L., Zhao, G. & Ding, X. Tandem assembly of the epothilone biosynthetic gene cluster by in vitro site-specific recombination. Sci. Rep. 1 (2011).

Yuzawa, S., Kapur, S., Cane, D. E. & Khosla, C. Role of a Conserved Arginine Residue in Linkers between the Ketosynthase and Acyltransferase Domains of Multimodular Polyketide Synthases. Biochemistry 51, 3708–3710 (2012).

Gibson, D. G. et al. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat. Methods 6, 343–345 (2009).

Shih, S. C. C. et al. A Versatile Microfluidic Device for Automating Synthetic Biology. ACS Synth. Biol. (2015).

Ellis, T., Adie, T. & Baldwin, G. S. DNA assembly for synthetic biology: from parts to pathways and beyond. Integr. Biol. 3, 109–118 (2011).

Zhu, B., Cai, G., Hall, E. O. & Freeman, G. J. In-Fusion™ assembly: seamless engineering of multidomain fusion proteins, modular vectors and mutations. Biotechniques 43, 354–359 (2007).

Sleight, S. C., Bartley, B. A., Lieviant, J. A. & Sauro, H. M. In-Fusion BioBrick assembly and re-engineering. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 2624–2636 (2010).

Zhou, Y. et al. Iterative Mechanism of Macrodiolide Formation in the Anticancer Compound Conglobatin. Chem. Biol. 22, 745–754 (2015).

Larionov, V., Kouprina, N., Gregory Solomon‡, Barrett, J.C. & Resnick, M.A. Direct isolation of human BRCA2 gene by transformation-associated recombination in yeast. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 94, 7384–7387 (1997).

Yamanaka, K. et al. Direct cloning and refactoring of a silent lipopeptide biosynthetic gene cluster yields the antibiotic taromycin A. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 111, 1957–1962 (2014).

Kvitko, B. H., McMillan, I. A. & Schweizer, H. P. An Improved Method for oriT-Directed Cloning and Functionalization of Large Bacterial Genomic Regions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 4869–4878 (2013).

Du, D. et al. Genome engineering and direct cloning of antibiotic gene clusters via phage ϕBT1 integrase-mediated site-specific recombination in Streptomyces. Sci. Rep. 5 (2015).

Itaya, M., Nagata, T., Shiroishi, T., Fujita, K. & Tsuge, K. Efficient Cloning and Engineering of Giant DNAs in a Novel Bacillus subtilis Genome Vector. J. Biochem. 128, 869–875 (2000).

Hou, Y., Li, F., Wang, S., Qin, S. & Wang, Q. Intergeneric conjugation in holomycin-producing marine Streptomyces sp. strain M095. Microbiol. Res. 163, 96–104 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding to Y.Z. from the Recruitment Program of Global Experts, funding to J.Y. from China/Shandong University International Postdoctoral Exchange Program, funding to J.F. from the International S&T Cooperation Program of China (ISTCP 2015DFE32850), funding to A.F. S. from the TUD Elite University Support the Best program. The authors acknowledge Vinothkannan Ravichandran’s help in proofreading this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Y. participated in the design of this study, performed data collection analysis and drafted the manuscript; H.M., X.Y., T.Q., F.Y., L.Q. and X.Z. participated in interpretation data; A.F.S. and R.M. helped with the revision of the final manuscript. J.F. and Y.Z. designed and oversaw the study, performed data interpretation and drafted the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Yin, J., Hoffmann, M., Bian, X. et al. Direct cloning and heterologous expression of the salinomycin biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptomyces albus DSM41398 in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Sci Rep 5, 15081 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep15081

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep15081

This article is cited by

-

An efficient method for targeted cloning of large DNA fragments from Streptomyces

Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology (2023)

-

Use of fusion transcription factors to reprogram cellulase transcription and enable efficient cellulase production in Trichoderma reesei

Biotechnology for Biofuels (2019)

-

Enhancement of neomycin production by engineering the entire biosynthetic gene cluster and feeding key precursors in Streptomyces fradiae CGMCC 4.576

Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology (2019)

-

Identification of a thermostable fungal lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase and evaluation of its effect on lignocellulosic degradation

Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology (2019)

-

Microbial synthesis of the type I polyketide 6-methylsalicylate with Corynebacterium glutamicum

Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.