Abstract

Cinnabar is a natural mercury sulfide (HgS) mineral of volcanic or hydrothermal origin that is found worldwide. It has been mined prehistorically and historically in China, Japan, Europe and the Americas to extract metallic mercury (Hg0) for use in metallurgy, as a medicinal, a preservative and as a red pigment for body paint and ceramics. Processing cinnabar via combustion releases Hg0 vapor that can be toxic if inhaled. Mercury from cinnabar can also be absorbed through the gut and skin, where it can accumulate in organs and bone. Here, we report moderate to high levels of total mercury (THg) in human bone from three Late Neolithic/Chalcolithic (5400–4100 B.P.) sites in southern Portugal that were likely caused by cultural use of cinnabar. We use light stable isotope and Hg stable isotope tracking to test three hypotheses on the origin of mercury in this prehistoric human bone. We traced Hg in two individuals to cinnabar deposits near Almadén, Spain and conclude that use of this mineral likely caused mild to severe mercury poisoning in the prehistoric population. Our methods have applications to bioarchaeological investigations worldwide and for tracking trade routes and mobility of prehistoric populations where cinnabar use is documented.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Perdigões is a Neolithic/Chalcolithic ditched enclosure site near Évora, south-central Portugal (Fig. 1) that was an important gathering place for over 1000 years (3400–2100 B.C.). The site functioned for ceremonial gatherings and for deposition of human and animal remains and offerings, often with ochre and/or cinnabar in association1,2; it also served as a celestial calendar3,4. Ongoing investigations at this site since 1997 have resulted in a multinational research program, the Global Program of Archaeological Research of Perdigões, to test hypotheses on the use and function of this site. One of the main hypotheses under investigation, referred to as the ‘mobility’ hypothesis, is that Perdigões was used by diverse groups from distant as well as local populations in Iberia. Preliminary analysis of strontium isotopes from human teeth supports this hypothesis2. Our initial objective was to determine if variation in light stable isotopes values (δ15N and δ13C) in human bone, which reflect diet (trophic level, plus marine versus terrestrial diets5,6) and latitude, as well as photosynthetic pathways of plant food7,8,9,10,11,12, would also support this ‘mobility’ hypothesis. Total mercury (THg) analysis of the bone was included as part of this study as significant variation in mercury exposure among individuals, presumably caused by differences in primary diets13, could also provide suitable data to test this hypothesis.

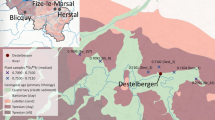

Map of Iberia with locations of major sites discussed in the text.

Modified from an outline map available online (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Iberian_Peninsula_location_map.svg) that is licensed under the Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license. The license terms can be found on the following link: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/.

While initially it was expected that mercury exposure would be minimal in the Perdigões population, our results on bone from 45 individuals from three Neolithic/Chalcolithic sites with group burial features were surprising. Most individuals had moderate to high levels of THg in their bone (range 0.06–188.9 μg/g with >10 μg/g in 31 individuals). As no previous study had analyzed THg in Neolithic/Chalcolithic human remains, the unexpectedly high level of exposure we observed became the main focus of our research. Here, we use a combination of light stable isotope (δ15N and δ13C), THg analyses of additional bone and soil and Hg isotope analysis to test three hypotheses on the source of this mercury and its potential impact on the health of this prehistoric population.

Results

We analyzed a total of 37 samples of human bone, five animal bones and eight soil samples from Perdigões. We also analyzed 11 human bone samples from two other Neolithic/Chalcolithic sites in southern Portugal: Sobreira de Cima (n = 5)14 where cinnabar also was identified with human burials15 and Monte Canelas I (n = 6 from three individuals) where no cinnabar was found associated with the burials16. Sobreira de Cima is a necropolis where five tombs containing hundreds of individuals in various states of preservation and articulation were excavated; ochre and cinnabar were found in all of these features and, in Tombs 2 and 3, these minerals were in sufficient quantities to form ‘red beds’ in the deposits14. Radiocarbon dates from four tombs range from 4080–4670 B.P. We choose five femora from five different stratigraphic units (UE11–15; Table S1) from Tomb I for analysis; cinnabar was identified with the burials from this tomb15, though no soil samples remain from the excavations for analysis.

Monte Canelas I is a hypogeum that contained over 6000 human bones from at least 150 individuals and dates to approximately 4400 B.P16. While most of these remains were scattered fragments, five primary burials were uncovered from the lower burial level of the hypogeum16. Of these, three were from adults: a middle-aged male (270), an old female (337) and a young adult female (342). Two bones from each of these individuals, a humerus and tibia, were analyzed for THg to help understand intra-skeletal variation. In all three individuals, the humerus had consistently higher mean ± SD THg (4.9 ± 1.9) than in the tibia (2.8 ± 1.0; Table S1).

The 37 human bones from Perdigões date from 3840 to 4430 B.P4. and include juveniles and adults of both sexes (Table S1). These remains were recovered from five burial features: Pits 7, 11 and 16 and Tombs I and II (Table S1). These features and the context of the burials within them are described by Valera et al.2 and Valera3; only Tombs I and II had ochre and cinnabar in association with the burials. The mean ± SD THg concentrations in known adult males (n = 7) and females (n = 8), respectively, were 67.1 ± 34.5 μg/g and 70.4 ± 69.0 μg/g with no significant difference between the two groups (t test, t = −0.117, p = 0.909; Table S1). Five juveniles, however, had a significantly lower mean THg concentration at 10.2 ± 17.3 μg/g than male and female adults combined (t < −3.53, p < 0.045). This latter result was expected as juveniles would have had less exposure time in life to accumulate mercury in their tissues, either through diet or other pathways. However, one juvenile from Sobreira de Cima had a very high THg value at 133.1 μg/g, indicating considerable exposure by this individual early in life.

We have identified three potential sources of the prehistoric mercury exposure in the human bone at Perdigões: diagenetic processes in the soil, dietary ingestion and cultural use of cinnabar. Here, we provide data that test each of these hypotheses to fully understand how mercury was impacting the prehistoric populations.

Diagenetic Hypothesis

When first encountering high levels of THg in the human bone from Perdigões, our initial reaction was that soil contamination was the primary cause. Mercury could be absorbed or intrude into the bone after burial by contact with contaminated soil. We investigated this possibility first as cinnabar, a natural mercury sulfide (HgS) that was used prehistorically in Iberia17,18 and ochre were found sprinkled over some of the human remains at Perdigões and was therefore an obvious source of contamination. Although cinnabar has very low solubility in soil water19, dissolution of HgS can occur in oxidized fluvial environments20,21 and in rare circumstances may then penetrate into bone pores and/or dentinal tubules in teeth22,23. In addition, tiny particles of cinnabar may have become embedded within the bone matrix, also causing the high THg concentrations. Thus, we chose to investigate these possibilities to further verify whether the mercury in the human bone was deposited there in vivo versus after burial.

Because all human remains recovered from Perdigões to date were excavated prior to our research, no in situ soil could be analyzed from the tombs. However, we were able to extract a small amount (<1 g) of soil still attached to the interior shaft of two of the 37 human bones from Tomb II atrium and chamber, respectively and from one pig (Sus sp.) bone recovered at the site (Table S1). Results on the human bone indicated that the soil contained either much higher (>50 μg/g) or lower (13.5 μg/g) THg than the bone from which it was extracted (Table 1 and Table S1). The soil attached to the pig bone also had a higher THg concentration (5.8 μg/g) than the bone itself (0.01 μg/g; Table 1). Thus, there are no emerging patterns in soil versus associated bone THg concentrations that might indicate diagenetic contamination. In addition, our analysis of the soil taken from the surface at the location of Tombs I and II and additional animal bones chosen at random across the site indicate lower levels of mercury in most of the soil and very low levels in animal bone compared to the human bones (Table 1), providing evidence that diagenetic processes were not responsible for deposition of mercury in human bone. The consistently different levels of THg in the humerus versus the tibia in three individuals at Monte Canelas I also are in accordance with in vivo deposition of mercury, with variation in skeletal elements and bone tissue types (trabecular versus cortical bone) based on blood flow and bone remodeling rates24. These results are similar to findings by Rasmussen et al.25,26,27 and Ávila et al.28 who also examined mercury contamination in bone from soil.

Scanning Electron Microscopy and Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) were performed on three human bones from Perdigões to examine the inner lattice structure and pore spaces of the compact bone and to quantify the elemental composition of the bone for any indication of cinnabar and/or intrusion of soil particles. We selected bone samples that had moderate to high THg for this analysis (40.0–137.4 μg/g; Table S1). The image for one of these samples (Fig. 2) indicate no apparent incursion of soil into the inner bone and is representative of all three samples in displaying a clean and well-preserved lattice. Further, the elemental analysis produced no detectable levels of Hg in the pore space or on the lattice in all three samples. These results support our conclusion that soil contamination is not the primary source of the high levels of THg in the human bone at Perdigões, though additional testing of human and animal bone and soil from future burial pits or tombs at Perdigões and other Neolithic/Chalcolithic sites where cinnabar was known to have been used is warranted.

Dietary Hypothesis

Our second hypothesis posits that mercury exposure in the prehistoric population was the result of dietary consumption of piscivorous marine and freshwater fish with elevated concentrations of methylmercury (CH3Hg), the most common means of mercury exposure in humans today13,29. As CH3Hg levels in consumer tissues usually correlate with trophic level of diet reflected by δ15N, we subsequently extracted collagen from all 45 bone samples for δ15N analysis (Table S1, but using only one bone from each of the burials from Monte Canelas I). Of these, ten samples were preserved well enough to produce an atomic C:N ratio between 2.9–3.6 that indicates reliable results30 (Table S2). These ten samples showed a weak negative relationship between δ15N and THg (Fig. 3; R2 = 0.0384), opposite of what is expected if dietary CH3Hg was the source of the THg in the bone.

To further investigate the effect of diet on THg concentrations, we analyzed CH3Hg concentrations in three bone samples (Perdigões, n = 2 and Sobreira de Cima, n = 1) to determine the proportion of THg that was CH3Hg. Methylmercury concentrations in these three samples ranged from 0.00137 to 0.00243 μg/g (all <0.05% of THg; Table S3), indicating that nearly all of the mercury in the bone is in the inorganic form. It should be noted that the proportion of CH3Hg may have been higher in vivo as it can demethylate via microbial processes in the soil environment. Thus, the concentration of CH3Hg in bone presented here represents only the organic mercury remaining in the bone at the time of analysis. These results, however, indicate that the high THg in the human bone from Perdigões and in two cases Sobreira de Cima, are not the result of ingestion of methylmercury in food.

Cultural Use of Cinnabar Hypothesis

Our third hypothesis regarding the source of mercury exposure is from the cultural use of cinnabar that resulted in accidental ingestion, inhalation, or absorption through the skin. Physiological pathways for mercury poisoning from cinnabar are reviewed by Liu et al.19 While raw cinnabar is much less toxic than CH3Hg, long term exposure, accidental ingestion and absorption through the skin and gut can lead to chronic effects with deposition of mercury occurring primarily in the kidney, liver and brain. Use of cinnabar as a pigment for pottery, for burial offerings, body paint or tattoos, could result in repeated exposure and accidental ingestion. If used as a medicinal, additional exposure would occur. Burning cinnabar releases highly toxic mercury vapor that can cause immediate effects, including death19. Moreover, all of these pathways were probably more limited in juveniles, with less exposure time in life and may account for the low levels of mercury found in most of their bones here.

One of the largest natural sources of mercury in the world is located at cinnabar mines near Almadén, Spain31,32,33, approximately 300 km ENE of Perdigões (Fig. 1). This mine was used by the Romans to extract mercury from the ores; laborers here often suffered high mortality as a result of these extraction processes34. Previous research on Pb isotope tracking has demonstrated that cinnabar was being mined here by the early Neolithic (6th millennium B.C. or ~7300 B.P.)18, supporting archaeological evidence for its use in the Neolithic of Spain17. Similarly, Hg isotopes have been used to successfully track mercury sources in ecological contexts as well as in one archaeological study where cinnabar mining in Peru caused high levels of Hg to be deposited in lake sediment35,36. Accordingly, we analyzed the same three samples of human bone used for CH3Hg analysis to characterize their Hg isotopic composition (δ202Hg and Δ199Hg). Results from the three bone samples indicate significant isotopic variation, with δ202Hg values ranging from −2.83%0 to −0.38%0 and Δ199Hg values ranging from −0.15%0 to +0.10%0 (Fig. 4; Tables S4–S5). These values demonstrate both mass dependent and mass independent fractionation of Hg isotopes relative to the NIST3133 standard. Significantly, the two Perdigões bone samples fall within the range of values previously determined for cinnabar ore from the Almadén region33 while the bone sample from Sobreira de Cima falls outside of this range (Fig. 4). The Hg isotopic compositions recorded at Perdigões are consistent with inheritance of high levels of inorganic Hg from Almadén cinnabar during the lifetimes of these individuals. The variation in the bone sample from Sobreira de Cima may reflect inheritance from another inorganic Hg source, possibly cinnabar, which has not yet been characterized for Hg isotopes.

Hg isotopic compositions.

Values (δ202Hg versus Δ199Hg) plotted include three Neolithic human bone samples (two from Perdigões, one from Sobreira de Cima) compared to cinnabar values from the Almadén mine, Spain. Note the isotopic similarity of the Perdigões samples to Almadén cinnabar, while the Sobreira de Cima sample has a much lower δ202Hg value (−2.83%0), outside the range of known values for cinnabar Hg.

Discussion

Only a few studies have previously investigated THg in archaeological human bone. Yamada et al.36 found high levels of THg (>100 μg/g) in 6–7th and 12–17th century burials in Japan that were equivalent and in some cases much greater, than levels found here. The authors attributed these high levels not to Hg in soil, where levels were low or undetectable, but to use of body paints containing Hg. Research by Rasmussen et al.24 on medieval human remains also documented Hg levels in bone ranging from <0.02 to 2.16 μg/g, attributed to the use of red ink and medicines containing mercury by monks. Cervini-Silva et al.22 and Ávila et al.28 applied high-resolution microdiffraction and x-ray diffraction analyses, respectively, to assess mercury presence in archaeological human bone in Mesoamerica where cinnabar was used as a preservative. While extensive use of cinnabar applied over bone can result in adsorption via fungal growth22 and a red stain on the bone surface23, Ávila et al.28 found that Hg in bone hydroxyapatite was likely caused by inhalation of Hg0 vapor and cinnabar dust in life or absorption through the skin.

Given that cinnabar was the likely source of most of the THg in human bone at Perdigões, the question remains as to whether this exposure was high enough to have caused mercury poisoning. Studies of bone as a biomarker for mercury exposure are rare and suggest that deposition of mercury into bone is minimal compared to other tissues25,38,39,40. One post-mortem study of workers at a smelter in Sweden who were exposed to inorganic Hg for more than ten years had <0.1 μg/g of THg in their bone40. An autopsy analysis of human subjects in Spain revealed detectable levels of mercury in liver and kidney tissue (0.14 and 0.25 μg/g, respectively) but <0.05 μg/g in bone39. Two studies on non-human mammalian subjects had similar results with bone having the lowest THg levels compared to other tissues41,42. It follows then that inorganic Hg inhaled, ingested or absorbed through the skin or gut from cinnabar will be deposited in bone in lesser amounts than in other tissues such as the kidney. If so, the levels of THg we observed in archaeological human bone would correspond with levels at least 5–10 times higher in the corresponding soft tissues. Thus, human bone with >10 μg/g THg likely represents a severe and chronic exposure that affected health and mortality. For comparison, THg in hair of 10 μg/g is considered to be the tolerance level for mercury exposure today, impacting motor function and vision13. However, no such guidelines exist for bone. Numerous other adverse effects to health are known to occur with both inhalation of Hg0 vapor and ingestion of Hg0 or Hg(II)43 and both of these pathways were probably occurring with prehistoric humans using cinnabar28.

Because cinnabar occurs in natural mineral deposits worldwide, with major sources in Spain, Europe and the Americas20, prehistoric use of these deposits would have increased Hg availability both locally and with trade or transport to other regions. The impact this may have had on the prehistoric population at Perdigões and at other Neolithic/Chalcolithic sites in Iberia regarding their health, social structure and cultural behavior is unknown, but likely was significant and is worthy of additional investigation. Our application of Hg isotope tracking in archaeological human bone also provides a new tool for investigating prehistoric mobility and the trade and transport of cinnabar from specific geological deposits where it was mined.

Methods

Total mercury analyses

Human bone samples were prepared by removing a small section of compact bone (2–3 cm wide) from the shaft of each sampled long bone. Though none of our samples had obvious cinnabar or red staining on the surface, each sample was thoroughly washed under running distilled water. After drying, the outer surface of each bone was removed using a 3/32 inch carbide bur and an NSK Ultimate XL micromotor. The drill operator wore latex gloves and a dust mask to prevent contamination. The tools and surface area were cleaned with ethanol after each sample was processed. Exposed inner bone was sampled with the drill and the powdered bone captured on a clean piece of aluminum foil, then transferred to a clean vial prior to analysis. For Hg isotope analysis of larger bone samples, 3–5 g of compact bone was prepared as described above, with all exposed surfaces (interior and exterior) removed using the drill. The bone was then rewashed in distilled water and pulverized to powder using a ceramic mortar and pestle. The mortar and pestle were cleaned after each use with ethanol and then rinsed with distilled water.

Soil samples were collected and stored in sterile plastic bags. Samples were freeze-dried to remove all moisture and then sieved through a 500 μm screen onto a clean piece of aluminum foil to remove coarse grains and rock; the sieve was washed with distilled water and ethanol after each sample. THg was measured with a Tri-Cell Direct Mercury Analyzer (DMA-80). Each set of 20 samples was preceded and followed by two method blanks, a sample blank and two samples each of standard reference material (DORM-4 and DOLT-5 from fish protein and dogfish liver, respectively and certified by the National Research Council, Canada).

SEM-EDS analysis

Three samples of inner compact bone, cleaned and prepared for THg analysis as described above, were mounted on aluminum stubs with carbon tape and coated with 10 nm of platinum-palladium (80:20) with a Cressington 208 HR sputter coater. The samples were imaged with the Philips XL30S FEG scanning electron microscope in secondary electron mode to choose areas for analysis. Once the areas of interests were chosen, each sample was examined utilizing the Phoenix EDAX non-dispersive x-ray microanalysis mode operated at 25 kV accelerating voltage. The minimum effective detection limit for Hg was 0.1%.

Light stable isotope analyses

Collagen was extracted from the powdered bone following published procedures44. First, the sample was demineralized in 10% HCl at room temperature until the reaction was complete. Residues were neutralized with deionized water by centrifugation. Next, humic acid was removed by treating the samples with 0.125 M NaOH for 20 hrs at room temperature. Samples were rinsed again with deionized water to neutral pH, dried overnight at 60 °C and homogenized. Samples were loaded into tin cups and processed using a Thermo Finnigan Flash 1112 EA coupled to a Thermo Finnigan Delta Plus XL via a Conflo III. Resulting carbon isotope ratios were corrected for 17O contribution using the Craig correction and reported in per mil notation relative to the VPDB scale. Nitrogen isotope ratios are reported in per mil notation relative to AIR. Carbon data were calibrated against the international standards L-SVEC (δ13C = −46.6%0 VPDB) and IAEA-CH6 (δ13C = −10.45%0 VPDB). Results with C:N ratios outside of a reliable range for well-preserved collagen (2.9–3.6)30 were disregarded.

Hg stable isotope analysis

Hg in three bone samples was extracted by using a 2-stage furnace combustion system. Ceramic boats containing approximately 0.02 g of bone were loaded into the first combustion oven which was heated to 750 °C over the course of six hours to release the Hg in the samples as Hg0. Hg0 released from the bone was transported through the second furnace (1000 °C) using Hg-free oxygen as a carrier gas and trapped in a highly oxidizing solution of 1% KMnO4 in 10% trace metal grade H2SO4. The Hg2+ in this solution was then neutralized using 5% hydroxylamine and reduced back to Hg0 using SnCl2 during a purge and trap separation process to concentrate the sample and remove any remaining combustion product matrix from the solution. Recoveries from the combustions and purge and trap for the three samples ranged from 83–116%; recovery was 95% for the standard reference material (DORM4, n = 1).

High precision isotope ratios were obtained with a multi-collector ICP-MS at the University of Michigan by continuous flow cold vapor generation using a Tl internal standard combined with standard-sample-standard bracketing to correct for instrumental mass bias45. Reported Hg isotope ratios use standard delta notation (in per mil units or %0), relative to the NIST SRM-3133 Hg internal standard46. 202Hg/198Hg ratios are reported as δ202Hg, which describes mass dependent fractionation (MDF). Capital delta notation (∆199Hg and ∆201Hg) is employed to express the deviation from mass dependence, or mass independent fractionation (MIF), of the odd isotopes 199Hg and 201Hg. The ability to distinguish small isotopic differences between samples is illustrated by the long-term precision obtained on the UM-Almadén Hg secondary standard, which is employed as an external standard for all experiments and has a long-term average (±2 SD) of −0.57 ± 0.08%0 (δ202Hg) and −0.02 ± 0.05%0 (∆199Hg).

Statistical analysis

Mean THg values for samples grouped by age and/or sex were compared with a two-tailed t test using JMP 11.0 with p < 0.05. Linear regression analysis was completed in Excel 2013.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Emslie, S. D. et al. Chronic mercury exposure in Late Neolithic/Chalcolithic populations in Portugal from the cultural use of cinnabar. Sci. Rep. 5, 14679; doi: 10.1038/srep14679 (2015).

References

Valera, A. C. [Mind the gap: Neolithic and Chalcolithic enclosures of south Portugal] Enclosing the Neolithic [ Gibson, A. (ed.)] [165–183] (Information Press, Oxford, 2012).

Valera, A. C., Silva, A. M., Cunha, C. & Evangelista, L. S. [Funerary practices and body manipulation at Neolithic and Chalcolithic Perdigões ditched enclosures (south Portugal)] Recent Prehistoric Enclosures and Funerary Practices in Europe [ Valera, A. C. (ed.)] [37–57] (BAR International Series 2676, Archaeopress, Oxford, 2014).

Valera, A. C. [Ditches, pits and hypogea: new data and new problems in south Portugal late Neolithic and Chalcolithic practices]. Funerary Practices in the Iberian Peninsula form the Mesolithic to the Chalcolithic [ Gibaja, J. F., Carvalho, A. F. & Chambon, P. (eds.)][103–112] (BAR International Series 2417, Archaeopress, Oxford, 2012).

Valera, A. C., Silva, A. M. & Romero, J. E. M. The temporality of Perdigões enclosures: absolute chronology of the structures and social practices. SPAL 23, 11–26 (2014).

Richards, M. P., Schulting, R. J. & Hedges, R. E. M. Sharp shift in diet at onset of Neolithic. Nature 425, 366 (2003).

Hedges, R. E. M. & Reynard, L. M. Nitrogen isotopes and the trophic level of humans in archaeology, J. Archaeolog. Sci. 34, 1240–1251 (2007).

Ogrinc, N. & Budja, M. Paleodietary reconstruction of a Neolithic population in Slovenia: a stable isotope approach. Chem. Geol. 218, 103–116 (2005).

Tykot, R. H. [Isotope analyses and the histories of maize] Histories of Maize: Multidisciplinary Approaches to the Prehistory, Biogeography, Domestication and Evolution of Maize [ Staller, J. E., Tykot, R. H. & Benz, B. F. (eds.)] [131–142] (Elsevier, 2006).

Oelze, V. M. et al. Early Neolithic diet and animal husbandry: stable isotope evidence from three Linearbandkeramik (LBK) sites in central Germany, J. Archaeolog. Sci. 38, 270–279 (2011).

Mays, S. & Beavan, N. An investigation of diet in early Anglo-Saxon England using carbon and nitrogen stable isotope analysis of human bone collagen, J. Archaeolog. Sci. 39, 867–874 (2012).

Waterman, A. J., Peate, D. W., Silva, A. M. & Thomas, J. T. In search of homelands: using strontium isotopes to identify biological markers of mobility in late prehistoric Portugal, J. Archaeolog. Sci. 42, 119–127 (2014).

Waterman, A. J., Silva, A. M. & Tykot, R. Stable isotopic indicators of diet from two late prehistoric burial sites in Portugal: an investigation of dietary evidence of social differentiation, Open J. Archaeom. 2:5258, 22–27 (2014b).

Driscoll, C. T., Mason, R. P., Chan, H. M., Jacob, D. J. & Pirrone, N. Mercury as a global pollutant: sources, pathways and effects, Environ. Sci. Tech. 47, 4967–4983 (2013).

Valera, A. C. Sobreira de Cima. Necrópole de hipogeus do Neolítico (Vidigueira, Beja), ERA Monográfica 1 (2013), Lisboa, Nia-Era.

Dias, C. & Mirão, J. [Identificação de pigentos vermelhos recolhidos no hipogeu da Sobreira de Cima por microscopia de Raman e micrscopia electrónica de varrimento acoplada com espectroscopia de dispersão de energias de Raios-X (MEV-EDX)] Sobreira de Cima. Necrópole de hipogeus do Neolítico (Vidigueira, Beja) [ Valera, A. C. (ed.) [101–108] (ERA Monográfica 1, Lisboa, 2013).

Silva, A. M. Paleobiology of the population inhumated in the hypogeum of Monte Canelas I (Alcalar – Portugal), XIII U.I.S.P.P. Congress Proceedings, Forlì, Italia, pp. 437–446 (1996).

Martín-Gil, J., Martín-Gil, F. J., Delibes-de-Castro, G., Zapatero-Magdaleno, P. & Sarabia-Herrero, F. J. The first known use of vermillion. Experientia 51, 759–761 (1995).

Hunt-Ortiz, M. A., Consuegra-Rodríguez, S., Díaz del Río-Español, P., Hurtado-Pérez, V. M. & Montero-Ruiz, I. [Neolithic and Chalcolithic –VI to III millennia BC-use of cinnabar (HgS) in the Iberian Peninsula: analytical identification and lead isotope data for an early mineral exploitation of the Almadén (Ciudad Real, Spain) mining district] History of Research in Mineral Resources. Cuadernos del Museo Geominero 13 [ Ortiz, J. E., Puche, O., Rábano, I. & Mazadiego, L. F. (eds.)] [3–13] (Instituto Geologico y Minero de Espana, Madrid, 2011).

Liu, J., Shi, J-Z., Yu, L-M., Goyer, R. A. & Waalkes, M. P. Mercury in traditional medicines: is cinnabar toxicologically similar to common mercurial? Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 233, 810–817 (2008).

Rytuba, J. J. Mercury from mineral deposits and potential environmental impact. Environ. Geol. 43, 326–338 (2003).

Holley, E. A., McQuillan, A. J., Craw, D., Kim, J. P. & Sander, S. G. Mercury mobilization by oxidative dissolution of cinnabar (α-HgS) and metacinnabar (β-HgS), Chem. Geol. 240, 313–325 (2007).

Cervini-Silva, J. et al. Cinnabar-preserved bone structures from primary osteogenesis and fungal signatures in ancient human remains, Geomicrobiol. J. 30, 566–577 (2013).

García-Alix, A., Minwer-Barakat, R., Suárez, E. M., Freudenthal, M. & Huertas, A. D. Cinnabar mineralization in fossil small mammal remains as a consequence of diagenetic processes, Lethaia 46, 1–6 (2012).

Rasmussen, K. L. et al. The distribution of mercury and other trace elements in the bones of two human individuals from medieval Denmark – the chemical life history hypothesis, Heritage Sci. 1, 1–13 (2013).

Rasmussen, K. L. et al. Mercury levels in Danish Medieval human bones, J. Archaeolog. Sci. 35, 2295–2306 (2008).

Rasmussen, K. L., Skytte, L., Ramseyer, N. & Boldsen, J. L. Mercury in soil surrounding medieval human skeletons, Heritage Sci. 1, 1–10 (2013b).

Rasmussen, K. L., Skytte, L., Jensen, A. J. & Boldsen, J. L. Comparison of mercury and lead levels in the bones of rural and urban populations in Southern Denmark and Northern Germany during the Middle Ages, J. Archaeolog. Sci.: Reports 3, 358–370 (2015).

Ávila, A., Mansilla, J., Bosch, P. & Pijoan, C. Cinnabar in Mesoamerica: poisoning or mortuary ritual? J. Archaeolog. Sci. 49, 48–56 (2014).

Sunderland, E. M. Mercury exposure from domestic and imported estuarine and marine fish in the US seafood market, Environ. Health Perspect. 115, 235–242 (2007).

DeNiro, M. J. Post-mortem preservation and alteration of in vivo bone collagen isotope ratios in relation to paleodietary reconstruction, Nature 317, 806–809 (1985).

Saupé, F. Geology of the Almadén mercury deposit, province of Ciudad Real, Spain. Econ. Geol. 85, 482–510 (1990).

Rytuba, J. J. & Klein, D. P. [Almaden Hg deposits] Preliminary compilation of descriptive geoenvironmental mineral deposit models [ Du Bray, E. A. (ed.)] [193–198] (U.S. Geological Survey, Open-File Report 95-831, Denver, 1995).

Gray, J. E., Pribil, M. J. & Higueras, P. L. Mercury isotope fractionation during ore retorting in the Almadén mining district, Spain. Chem. Geol. 357, 150–157 (2013).

Lane, R. W. [The Wissenschaften of toxicology] Hayes’ Principles and Methods of Toxicology 6thEd. [ Hayes, A. W. & Kruger, C. L. (eds.) [3–33] (CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, 2014).

Cooke, C. A. et al. Use and legacy of mercury in the Andes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 4181–4188 (2013).

Cooke, C. A., Balcom, P. H., Biester, H. & Wolfe, A. P. Over three millennia of mercury pollution in the Peruvian Andes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 8830–8834 (2009).

Yamada, M. et al. Accumulation of mercury in excavated bones of two natives in Japan. Sci. Total Environ. 162, 253–256 (1995).

Bush, V. J., Moyer, T. P., Batts, K. P., & Parisi, K. E. Essential and toxic element concentrations in fresh and formalin-fixed human autopsy tissues. Clin. Chem. 41, 284–294 (1995).

Garcia, F., Ortega, A., Domingo, J. L. & Corbella, J. Accumulation of metals in autopsy tissues of subjects living in Tarragona County, Spain. Environ. Sci. Health A36, 1767–1786 (2001).

Lindh, U., Brune, D., Nordberg, G. & Wester, P.-O. Levels of antimony, arsenic, cadmium, copper, lead, mercury, selenium, silver, tin and zinz in bone tissue of industrially exposed workers. Sci. Total Environ. 16, 109–116 (1980).

Brookens, T. J., O’Hara, T. M., Taylor, R. J., Bratton, G. R. & Harvey, J. T. Total mercury body burden in Pacific harbor seal, Phoca vitulina richardii, pups from central California. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 56, 27–41 (2008).

Halffman, C. M. Bone as a biomarker of mercury exposure in prehistoric Arctic human populations: initial method validation using animal models. PhD thesis, Univ. of Alaska, Fairbanks (2009).

Tchounwou, P. B., Ayensu, W. K., Ninashvili, N. & Sutton, D. Environmental exposure to mercury and its toxicopathologic implications for public health. Environ. Toxicol. 18, 149–175 (2003).

Leyden, J. J., Wassenaar, L. I., Hobson, K. A. & Walker, E. G. Stable hydrogen isotopes of bison bone collagen as a proxy for Holocene climate on the Northern Great Plains. Palaeogeogr., Palaeoclimatol., Palaeoecol. 239, 87–99 (2006).

Bergquist, B. A. & Blum, J. D. Mass-dependent and mass-independent fractionation of Hg isotopes by photo-reduction in aquatic systems. Science 318, 417–420 (2007).

Blum, J. D. & Bergquist, B. A. Reporting the variations in the natural isotopic composition of mercury. Ann. Bioanal. Chem. 388, 353–359 (2007).

Acknowledgements

Funds for travel to conduct field work were provided by UNCW Department of Biology and Marine Biology and the Office of International Programs. We thank Kim Duernberger and Dinka Besic for help with stable isotope facilities and sample preparation at UNCW and University of Saskatchewan, respectively. We also thank M. Tsui for analytical support needed for Hg isotope sample preparation and Mark Gay for assistance with the operation of the scanning electron microscope. Marcus Johnson assisted with Hg isotope mass spectrometry. Special thanks are given to the owners of Herdade do Esporão, where Perdigões is located, for their support of the excavations there since 1997.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.D.E. designed the study, coordinated sample analysis and wrote the initial paper. R.B. and A.M. performed laboratory analyses and contributed to the manuscript. W.P.P. conducted stable isotope analyses and added to interpretations. J.B. and J.G. performed Hg stable isotope analyses and helped refine interpretations and discussion. A.V. and A.M.S. provided archaeological human bone samples and contributed to the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Emslie, S., Brasso, R., Patterson, W. et al. Chronic mercury exposure in Late Neolithic/Chalcolithic populations in Portugal from the cultural use of cinnabar. Sci Rep 5, 14679 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep14679

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep14679

This article is cited by

-

An archaeometric approach to biocontamination with manganese pigments in ancient marine hunter-gatherers of the Atacama Desert: health, ideological, and socioecononic considerations

Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences (2023)

-

Beautiful, Magic, Lethal: a Social Perspective of Cinnabar Use and Mercury Exposure at the Valencina Copper Age Mega-site (Spain)

Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory (2023)

-

Pigments for the dead: megalithic scenarios in southern Europe

Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences (2023)

-

Using multi-technology to characterize transboundary Hg pollution in the largest presently active Hg deposit in China

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2023)

-

Geochemical analysis of multi-element in archaeological soils from Tappe Rivi in Northeast Iran

Acta Geochimica (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.