Abstract

Freestanding yet flexible membranes of MnO/carbon nanofibers are successfully fabricated through incorporating MnO2 nanowires into polymer solution by a facile electrospinning technique. During the stabilization and carbonization processes of the as-spun membranes, MnO2 nanowires are transformed to MnO nanoparticles coincided with a conversion of the polymer from an amorphous state to a graphitic structure of carbon nanofibers. The hybrids consist of isolated MnO nanoparticles beading in the porous carbon and demonstrate superior performance when being used as a binder-free anode for lithium-ion batteries. With an optimized amount of MnO (34.6 wt%), the anode exhibits a reversible capacity of as high as 987.3 mAh g−1 after 150 discharge/charge cycles at 0.1 A g−1, a good rate capability (406.1 mAh g−1 at 3 A g−1) and an excellent cycling performance (655 mAh g−1 over 280 cycles at 0.5 A g−1). Furthermore, the hybrid anode maintains a good electrochemical performance at bending state as a flexible electrode.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Flexible lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) hold great promise for the next generation energy sources of future electronic devices. They have found a wide variety of promising applications including smart clothes, electronic skins and wearable sensors and so on1,2. As core components of flexible LIBs, flexible electrodes are usually made from various functional organic and/or inorganic materials build on/in film-like carbon based materials from carbon nanotubes (CNTs)3,4,5, graphene6,7,8, carbon cloth/textiles9,10,11,12, etc. Besides, a preferable mass loading of active materials is important to maximum their utilization in hybrids. Due to the low cost and easy processing, carbon nanofibers (CNFs) membrane has advantages for being used as a free-standing and flexible substrate to construct metal or metal oxides/carbon composites13. The electrospinning process followed by stabilization and carbonization has been proved to be a facile and controllable way for fabricating CNFs membranes14. Some CNFs-based systems, such like Ge/CNFs15, Se/CNTs16, Ti/CNFs17, MoS2/CNFs18 have been fabricated and investigated for flexible electrode of LIBs or Sodium-ion batteries (SIBs). Therefore, it is highly desired if a proper form of metal compound is introduced in CNFs in-situ during the fabrication of CNFs membranes.

Recently, Mn-based nanomaterials have been intensively studied for energy storage19,20,21. MnO has attracted much attention because of its high theoretical capacity (756 mAh g−1), low conversion potential (average discharge and charge voltages of 0.5 V and 1.2 V vs. Li/Li+, respectively), environmentally benign features and low cost22,23,24. To tackle its shortcomings of capacity fading and poor rate capability, some MnO-carbon hybrids have been developed, such as MnO/mesoporous carbon25,26, MnO/graphene23,27,28,29,30, MnO/carbon21 nanowires31,32,33 and MnO/CNTs34,35,36, etc. However, in most cases the aforementioned products were in powder. Although Huang’s group fabricated MnO/CNFs composite by an electrospinning technique, a polymeric binder was still used for the fabrication of the electrodes31. Herein, we demonstrated the synthesis of MnO nanoparticles (NPs) beading in CNFs membranes by introducing MnO2 nanowires (NWs) into the polyacrylonitrile (PAN) solution through electrospinning followed by stabilization and carbonization processes. Structural transformation from MnO2 NWs to MnO NPs was accompanied by the simultaneous conversion of amorphous polymer to porous graphitic CNFs. The obtained membranes with MnO NPs uniformly embedded in the porous CNFs could be used directly as binder-free electrode for flexible LIBs. Effects of the loadings of MnO NPs in CNFs on the electrochemical performance of the composites were also investigated. With a preferable loading of MnO (34.6 wt%), the MnO/CNFs (MnC) membrane exhibits a high reversible capacity of 987.3 mAh g−1 after 150 discharge/charge cycles at 0.1 A g−1, a good rate capability (406.1 mAh g−1 at 3 A g−1) and an excellent cycling performance (655 mAh g−1 over 280 cycles at 0.5 A g−1). Besides, the hybrid membrane shows good electrochemical performance at bending state, demonstrating a great potential as a high performance anode material for flexible LIB applications.

Results

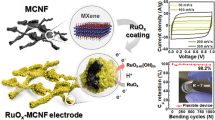

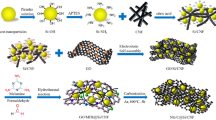

Figure 1 illustrates the fabrication process of the flexible MnC membrane as reported previously37. Typically, a homogeneous blend solution with MnO2 nanostructures dispersed in PAN/ dimethylformamide (DMF) was electrospun into nanofibers, following with stabilization in air and a carbonization process in an inert gas. The fabricated MnO2/PAN nanofiber (MnP) membranes have a dark grey color due to the existence of MnO2 and the color is changed to black after carbonization. Different from our previous work37, in which a rod-like hierarchical core-corona nanostructure was prepared by a hydrothermal method, here we selected MnO2 NWs as Mn source, which are more likely uniaxially aligned along the CNFs. SEM image of pristine MnO2 NWs (Fig. 2(a)) displays monodispersed nanostructures with an average length of 1–2 μm and a diameter of 20–30 nm. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of MnO2 NWs (Fig. 2(b)) shows the typical diffraction peaks which can be indexed to α-MnO2 phase (JCPDS 44-0141). The peaks at 12.8°, 18.1°, 28.8° and 37.5° can be clearly seen from the as-spun MnP membrane, which are attributed to the diffractions from (110), (200), (310) and (211) faces of α-MnO238,39, respectively, suggesting well-maintained crystal nanostructures of MnO2 NWs in MnP membrane. After carbonization, no α-MnO2 diffraction peaks but strong peaks at 35.0°, 40.6°, 58.6° and 70.3° are observed, assigned to the (111), (200), (220) and (311) reflections of cubic MnO (JCPDS 78-0424), respectively. Accompanying with the structural transformation from α-MnO2 to MnO crystals, the PAN has been carbonized to carbons at the high temperature in an inert atmosphere, as evidenced by the diffraction peak appearing at around 26.5° in the XRD spectra of MnC membrane. Comparing with the XRD curve of graphite (Figure S1), which shows a very sharp peak at around 26.5°, the obtained carbon nanofibers here is believed to be composed of amorphous and graphitic carbon.

Raman spectroscopy was further used to confirm the existence of MnO and carbon (Fig. 2(c)). The signals observed at 365 and 645 cm−1 can be ascribed to Mn-O vibrations according to the literatures23. Two peaks at around 1350 and 1587 cm−1 are obtained, corresponding to D and G bonds of graphitic carbon, respectively40. The presence of D band suggests the existence of defects in the sample, which has been well characterized for more Li storage sites than graphitic carbon41. The X-ray photoelectron electroscopy (XPS) spectrum of MnC membrane (Figure S2 (a)) confirmed the presence of Mn, O and C elements and the C 1 s spectrum (Figure S2 (b)) could be decomposed into six components including C(sp2) (286.4 eV), C(sp3) (285.4 eV), C-O (286.1 eV), C = O (287.8 eV), O-C = O(298.5 eV) and π-π*(291.7 eV). The two signals at 641.4 eV and 562.6 eV from the Mn 2p XPS spectrum (Fig. 2(d)) could be attributed to Mn(II)2p3/2 and 2p1/2, respectively, characteristic of Mn in MnO23,42. Besides, a splitting satellite peak was found at 6.1 eV above the 2p1/2 principal peak, further indicating the existence of MnO43,44. Energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) mapping images (Figure S3) also confirm the existence of Mn, O and C elements.

The MnO2 content in MnP membranes were tuned by adjusting the amount of MnO2 NWs in PAN/DMF solutions before electropinning; three samples are denoted here as MnP-1 (10 wt%), MnP-2 (20 wt%) and MnP-3 (30 wt%). The corresponding MnC membranes are designated as MnC-1, MnC-2 and MnC-3, respectively. The mass loading of MnO in the final products was estimated by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA, Figure S4). The mass loss from 150–400 °C is related to the combustion of carbon24 and the weight increase from 700–900 °C is due to the reaction:  41,45. Considering the weight increase from MnO to Mn2O3, the calculated contents of MnO in MnC were 15.8 wt%, 34.6 wt% and 50.6 wt% for MnC-1, MnC-2 and MnC-3, respectively. The lower temperature of carbon combustion for samples with higher MnO contents can be explained by the catalytic function of the Mn species in the composites46.

41,45. Considering the weight increase from MnO to Mn2O3, the calculated contents of MnO in MnC were 15.8 wt%, 34.6 wt% and 50.6 wt% for MnC-1, MnC-2 and MnC-3, respectively. The lower temperature of carbon combustion for samples with higher MnO contents can be explained by the catalytic function of the Mn species in the composites46.

SEM and TEM images for MnP and MnC membranes are shown in Fig. 3. We can see that the as-spun nanofibers in MnP membranes (Fig. 2(a–c)) have uniform diameters of 200–300 nm and lengths of up to several micrometers. Before thermal treatment, MnO2 NWs are embedded in the co-axial nanofibers. Such a morphology has been observed from the samples with various loadings, except for some MnO2 NWs bundles being observed in MnP-2 and MnP-3 (insets of Fig. 3(b,c)). After carbonization, the morphologies and diameters of nanofibers in MnC membranes are well maintained. Interestingly, the MnO2 NWs are broken into MnO NPs with a typical diameter of 20–30 nm, leading to the formation of MnO NPs embedded in the CNFs (insets of Fig. 3(d,e)). Few additional particles were observed on the exterior surface of nanofibers for MnC-1 and MnC-2, but a large addition of MnO2 led to an accumulation of MnO NPs on the external structure for MnC-3 (Fig. 3(d)).

The cross-section view of nanofibers in MnC-2 membrane (Fig. 4(a)) displays a rough and porous structure with a pore diameter of about 20–30 nm. TEM image (Fig. 4(b)) further confirms the existence of the tubular pores inside nanofibers. The formation of such a porous structure could be attributed to the transformation of Mn-oxides especially accompanying the carbonization of PAN fibers, which is in favor of the access of electrolyte ions to active materials and of buffering the volumetric expansion during the Li+ insertion/extraction. N2 adsorption/desorption isotherm and the pore size distribution of MnC-2 (Fig. 4(d)) suggests that numerous mesopores are indeed present with diameters ranging between 20–50 nm. With such a mesoporous structure, the electrodes may provide a continuous network for fast electron/Li+ transportation and for tolerance of volumetric change, leading to a relatively high capacity and good cycling stability. The high resolution TEM image (Fig. 4(c)) shows clear lattice fringes for graphitic structure and Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) of the red square area demonstrates (002) of carbon and (220), (111) diffraction points of MnO, further indicating that the obtained product is dominant by MnO particles.

XRD was employed to investigate the structural evolution of Mn-oxides during the thermal treatment process. Several samples were obtained by stabilization at 280 °C in air for 2 h followed without/with carbonization at different temperatures (500–1000 °C) in N2 for 2 h (Figure S5). The sample obtained by stabilization at 280 °C alone shows the characteristic peak of MnO2. However, diffractions at 35.0o, 40.6o and 58.7o appear after carbonization at 500 °C, indicating the formation of MnO crystals. The MnO signals become stronger and sharper with increase of temperature, suggesting the improved crystallinity of MnO. The diffraction peaks around 26.5o becomes notable after 900 oC, indicating the formation of graphitic carbon. In a control experiment, MnO2 NWs was treated under the same condition without PAN fibers. Large MnO particles with diameters of 200–300 nm were obtained (Figure S6), dramatically different from that of MnC. The structural transformation of MnO2 NWs is significantly different when PAN fibers are present. It is known that stabilization and carbonization are two vital steps taking place during the thermal treatment of PAN-based CNFs: a ladder-like structure could be formed at the early stabilization stage with dehydrogenation and cyclization reactions and then an aromatic growth and polymerization occur to generate a turbostratic structure14. Here, in our work, the resultant MnO NPs embedded in porous CNFs might be related to the strong synergistic effects between the morphological evolution of Mn-oxides and the structural transformation of PAN from an amorphous to graphitic carbons.

Free-standing MnC membranes have been directly used as anodes in coin-type Li half-cells and their electrochemical performance were investigated. The initial cyclic voltammograms (CV) curve of MnC electrode (Fig. 5(a)) shows an irreversible reduction peak at around 0.72 V in the first cycle, corresponding to the irreversible reduction of electrolyte and the formation of a solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) layer47,48. Another obvious cathodic peak close to 0.11 V is attributed to the initial reduction of Mn2+ to metallic Mn0 ( ), which significantly shifts to 0.48 V in the following cycles. The shift is probably due to the enhanced kinetics and enhanced utilization efficiency of MnO NPs in the hybrid electrode, arising from the microstructure alternation after the first lithiation30,49. During the anodic scan, the oxidation peak at about 1.29 V can be ascribed to oxidation of Mn0 to Mn2+ (

), which significantly shifts to 0.48 V in the following cycles. The shift is probably due to the enhanced kinetics and enhanced utilization efficiency of MnO NPs in the hybrid electrode, arising from the microstructure alternation after the first lithiation30,49. During the anodic scan, the oxidation peak at about 1.29 V can be ascribed to oxidation of Mn0 to Mn2+ ( ), which slightly shifts to 1.31 V. The second and onward CV curves indicate a good reversibility and structural stability of MnC during the electrochemical process. On the contrary, those of bare MnO NPs (Fig. 5(b)) display a reducing tendency in capacity for the initial several cycles.

), which slightly shifts to 1.31 V. The second and onward CV curves indicate a good reversibility and structural stability of MnC during the electrochemical process. On the contrary, those of bare MnO NPs (Fig. 5(b)) display a reducing tendency in capacity for the initial several cycles.

The discharge/charge curves of the MnC and MnO electrodes (Fig. 5(c)) demonstrate a higher specific capacity of MnC than that of MnO and a larger value of MnC-3 with a higher content of MnO. As summarized in Table 1, the initial discharge capacities of MnC-1, MnC-2 and MnC-3 in the first cycle are 1114.4, 1220.0 and 1363.6 mAh g−1 respectively, indicating a high accessibility for Li+ insertion/extraction in the MC electrodes. In addition, the initial columbic efficiency (CE) of MnC-1, MnC-2 and MnC-3 is 80.7%, 86.1% and 72.3% respectively, higher than that of MnO (69.1%) and the reported MnO/carbon and MnO/graphene composites27,29,41. The results show that the stable structure of CNFs in our MnC membranes could effectively reduce the pulverization of MnO and etching by electrolyte, thus limiting the production of thicker SEI layer during the initial discharge/charge process50. A lower CE of MnC-3 than that of MnC-1 or MnC-2 could be attributed to the unfavorable formation of SEI layers caused by the aggregation of MnO NPs. The discharge/charge curves (Fig. 5(d)) for MnC in the different cycles at 0.1 A g−1 demonstrate that the hybrids gradually reach a stable status in the second and subsequent cycles.

The rate performance was investigated by increasing the current density stepwise from 0.1 A g−1 to 3 A g−1 and subsequently coming back to 0.1 A g−1 and then the cycling performance were evaluated by the following 100 discharge/charge cycles at 0.1 A g−1 (Fig. 6(a)). It is obvious that MnC electrodes displays much higher capacities than that of MnO (Figure S7) and MnC-2 shows a better rate performance although it processes lower discharge capacities in the first two stages (0.1 and 0.2 A g−1) than that of MnC-3. The average reversible capabilities of MnC-2 are 918.7, 785.4, 610.6 and 532.2 mAh g−1 at 0.1 A g−1, 0.2 A g−1, 0.5 A g−1 and 1 A g−1, respectively. Even at a high rate of 3 A g−1, the discharge capacity of 406.1 mAh g−1 remains about 44.1% of the initial value at 0.1 A g−1. While MnC-3 and MnC-1 sample only retain 39.5% and 38%, respectively. When the current density is switched back to 0.1 A g−1 after 50 cycles at various current densities, a reversible capacity of 927.1 mAh g−1 is recovered for MnC-2, higher than its initial value at the same rate. However, MnC-3 only delivers 911.6 mAh g−1 in the same case. Furthermore, in the following cycling tests at 0.1 A g−1, a reversible capacity of as high as 987.3 mAh g−1 are obtained for MnC-2 but the value of MnC-3 falls to 898.1 mAh g−1. As shown in Fig. 3, the aggregation of MnO NPs protruding out of the external structure for MnC-3 might reduce the conductivity of the electrode and weaken the cushion effects of carbon materials, thus leading to a declined capacity. Moreover, MnC-1 and MnC-2 display reduced charge transfer resistance (Rct) after 10 cycles (smaller than that of MnO, Figure S8), but a large increase of SEI layer (RSEI) and Rct of MnC-3 is obtained from the Nyquist plots after cycling (Fig. 6(b) and Table S1), suggesting MnC-3 possessing continuous formation of SEI layer and a slower charge transfer rate.

(a) rate capacities at different current densities and capacity at different cycles for MnC and MnO; (b) Nyquist curves of MnC samples at 1st and 10th cycle and their respective fittings with an appropriate electric equivalent circuit; (c) cycling performance of MnC-2 with columbic efficiency; (d) a comparison of the discharge capacities of MnC-2 with reported MnO-based materials at various cycles.

The cycling curve of MnC-2 at 0.5 A g−1 and the corresponding CE value (Fig. 6(c)) further demonstrate that it possesses an excellent cycling performance with a columbic efficiency of ~99%. It should be noted that the capacity of MnC-2 firstly drops and then increases upon cycling, which is probably due to the activation process during the discharge/charge process for MnO/C hybrids20,30,39,47. After 280 cycles, the reversible capacity retains a high value of 655 mAh g−1, higher than the reported value for porous MnO/C core/shell hybrids, e.g., 618.3 mAh g−1 after 200 cycles at 0.5 A g−1 51. A comparison of the capacities of MnC-2 with those of reported MnO-based materials after various cycles (Fig. 6(d)) clearly shows that out MnC hybrids display a better cycling performance. Furthermore, SEM and TEM images after cycling turn out to be a direct proof of the structural stability and integrity of the materials (Figure S9). No pulverization or obvious size variation is observed, indicating that such hybrids can indeed relieve the strain and stress caused by volume variation and prevent the aggregation or detachment of inner MnO NPs over cycling process.

Discussion

As discussed, with appropriate contents of MnO NPs, i.e., 34.6 wt% in our work, a favorable porous structure with the active materials being well confined in CNFs are obtained, leading to an improvement of Li reaction kinetics and giving rise to a comprehensively improved electrochemical properties including high specific capacities, rate performance and cycling stability. Several unique characteristics of the MnC membrane could contributed to the high performance anode material in LIBs: (i) the conductive networks arising from CNFs increases the conductivity of the electrode and provide fast transfer paths for electrons and Li ions; (ii) the porous structure of MnC promotes the diffusion of the liquid electrolyte into the bulk of anode materials, thus improving the efficient utilization of the active materials and giving rise to high capacities; (iii) the architecture with MnO NPs well beading in CNFs is in favor of relieving the strain induced by the volume change during the charge/discharge cycles, leading to an enhanced cycle stability. Furthermore, to investigate the potential of as-prepared samples for use as flexible electrodes, a flexible cell was assembled and tested to obtain the effect of bending on the electrochemical performance (Fig. 7). It is obvious that the capacity of the battery being bent have a negligible decrease compared with that of the original flat battery. Moreover, the flexible battery showed a good cyclic stability both under flat and bent states. With respect to the original capacity, it showed a capacity retention of ~93.8% after the first 12 cycles under a flat state and ~84% after another 20 cycles under a bent state. Such a facile and practical fabrication process of MnC membranes might be an efficient route to design and fabricate high performance flexible electrode materials for LIBs.

In summary, we have successfully fabricated MnC membranes through incorporating MnO2 NWs into the electrospun solution by a facile and practical electrospinning technique followed by stabilization and carbonization processes. During the thermal treatment, structural changes from MnO2 NWs to MnO NPs occurred accompanying with the conversion from an amorphous state of polymer to a graphitic structure of CNFs. The resultant MnC architecture with MnO NPs being well embedded in the porous carbon structures not only facilitates the transport of both electrolyte ions and electrons to the electrode surface, but also enhances the utilization of the active materials. With suitable amounts of MnO NPs, the resultant flexible MnC membrane demonstrates excellent electrochemical properties with high specific capacitie of 987.3 mAh g−1 after 150 discharge/charge cycles at 0.1 A g−1, good rate performance (406.1 mAh g−1 at 3 A g−1) and cycling stability (655 mAh g−1 over 280 cycles at 0.5 A g−1). We believe that such low cost, high-performance hybrids fabricated by earth-abundant and environmentally friendly materials and scalable electrospinning techniques can offer a great promise in grid-scale electrode materials for flexible LIBs.

Experimental Section

Materials

Polyacrylonitrile (PAN, Mw = 80000) was made in laboratory52. Potassium permanganate (KMnO4, AR), sulfuric acid (H2SO4, AR) and N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, AR) were purchased from Shanghai Lingfeng Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Manganese sulfate monohydrate (MnSO4·H2O, AR) was purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. All these reagents were used without further purification.

Preparation of MnO2 nanowires (MnO2 NWs)

MnO2 NWs were synthesized by a hydrothermal method. Briefly, aqueous solutions of MnSO4·H2O (1 mmol) and KMnO4, (1.5 mmol) (Mn(II)/Mn(VII) = 3:2) were mixed with vigorously stirring. The PH value of the mixture was adjusted ~2 with 5 M H2SO4 aqueous solution. Then the solution was transferred to an autoclave and reacted in oven at 140 °C for 12 h. After cooling down, the product was collected by filtration and washed repeated with distilled water and absolute ethanol. Then the MnO2 NWs powder was obtained.

Preparation of MnO2 NWs/PAN nanofiber (MnP) membranes

The obtained MnO2 NWs powder was washed three times with DMF, centrifuged and then added into a certain-mass 8 wt% PAN/DMF solution as an electrospinning solution. Intensive stirring was conducted for 12 h in order to get a homogeneously distributed solution. Then the blended solution was electrospun into MnP membranes, with a controlled syringe pump of 25 μL min−1 and an applied voltage of 20 kV with a distance of 20 cm between the electrospinning jet and the collector. The adding amounts of MnO2 NWs based on PAN were 10 wt%, 20 wt% and 30 wt% for MnP-1, MnP-2 and MnP-3, respectively.

Preparation of MnO/carbon nanofiber (MnC) membranes

The as-prepared MnP membranes were firstly performed at 280 °C in air for 2 h for a stabilization process. Next, the temperature increased to 1000 °C with a heating rate of 3 °C/min and stayed for 1 h in N2 atmosphere. Then the MnC membranes were obtained after the furnace cooling down to the room temperature. During both the stabilization and carbonization processes, the membranes were sandwiched between two aluminum oxide (Al2O3) plates to give certain tensions against the planer dimensional shrinkage. For the controlled experiment, MnO2 NWs powder was treated with the similar procedure in a Al2O3 container.

General characterization

The structure of the obtained samples was characterized by X-Ray diffraction (XRD) measurement was conducted on a Rigaku D-max-2500 diffractometer with nickel-filtered Cu- Kα radiation with λ = 1.5406 Å. The morphology and microstructure of the composites were characterized by field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM, Hitachi S-4800) in conjunction with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEOL JEM-2100) at an accelerating voltage of 100 kV. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA, Perkin-Elmer TGA 4000) was measured with a heating rate of 5 °C/min under 20 mL/min of flowing air. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) experiment was carried out on a RBD upgraded PHI-5000C ESCA system (Perkin Elmer) with Mg Kα radiation (hν = 1253.6 eV). The measurement of the nitrogen adsorption isotherms was done with a Quantachrome Nova 2000 at 77. 4 K. Raman spectra were recorded using a LabRam -1B Ramen spectroscope with He-Ne laser excitation at 632.8 nm and scanning for 50 s.

Electrochemical characterization

The obtained MnC membranes were punched into 1 cm diameter electrodes and could be used directly. For MnO electrode, homogeneous slurry composed of MnO powder, poly(vinyl difluoride) (PVDF) and acetylene black in N-methyl-2-pyrrolidinon (NMP) with a weight ratio of 60:10:30 was prepared under magnetic stirring for 12 hours and then was coated onto clean copper foil (∼10 μm) current collector. All the electrodes were firstly dried in a vacuum oven at 60 °C overnight and then assembled into LR 2032 type coin cells in an argon-filled glove box. The electrolyte was 1 M solution of LiPF6 in ethylene carbonate (EC) and dimethyl carbonate (1:1, v/v). Microporous polypropylene sheet (Celgard, 2400) was used as the separator. The galvanostatic discharge/charge cycles of the cells were performed over the potential range between 0.01 and 3.0 V on Land instrument (CT2001A). Cyclic voltammetry (CV) and the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) were performed on Autolab PGSTAT 302N electrochemical workstation with a scan rate of 0.2 mV s−1 from 0.01 V to 3 V and by applying a perturbation voltage of 10 mV in a frequency range of 100 kHz to 10 mHz at the open circuit potential, respectively.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Zhao, X. et al. Membranes of MnO Beading in Carbon Nanofibers as Flexible Anodes for High-Performance Lithium-Ion Batteries. Sci. Rep. 5, 14146; doi: 10.1038/srep14146 (2015).

References

Gwon, H. et al. Recent progress on flexible lithium rechargeable batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 538–551 (2014).

Zhou, G., Li, F. & Cheng, H. M. Progress in flexible lithium batteries and future prospects. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 1307–1338 (2014).

Zhang, Y. et al. Flexible and Stretchable Lithium-Ion Batteries and Supercapacitors Based on Electrically Conducting Carbon Nanotube Fiber Springs. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 53, 14564–14568 (2014).

Jia, X. et al. Building flexible Li4Ti5O12/CNT lithium-ion battery anodes with superior rate performance and ultralong cycling stability. Nano Energy 10, 344–352 (2014).

Weng, W. et al. Flexible and stable lithium ion batteries based on three-dimensional aligned carbon nanotube/silicon hybrid electrodes. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2, 9306–9312 (2014).

Qiu, W., Jiao, J., Xia, J., Zhong, H. & Chen, L. A. Self-Standing and Flexible Electrode of Yolk-Shell CoS2 Spheres Encapsulated with Nitrogen-Doped Graphene for High-Performance Lithium-Ion Batteries. Chem-eur. J. 21, 4359–4367 (2015).

Zeng, G. et al. A general method of fabricating flexible spinel-type oxide/reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite aerogels as advanced anodes for lithium-ion batteries. ACS nano 9, 4227–35 (2015).

Rana, K., Kim, S. D. & Ahn, J. H. Additive-free thick graphene film as an anode material for flexible lithium-ion batteries. Nanoscale 7, 7065–7071 (2015).

Balogun, M. S. et al. Titanium dioxide@titanium nitride nanowires on carbon cloth with remarkable rate capability for flexible lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 272, 946–953 (2014).

Yu, H. et al. Three-dimensional hierarchical MoS2 nanoflake array/carbon cloth as high-performance flexible lithium-ion battery anodes. J. Mater. Chem. A 2, 4551–4557 (2014).

Long, H. et al. Growth of Hierarchal Mesoporous NiO Nanosheets on Carbon Cloth as Binder free Anodes for High-performance Flexible Lithium-ion Batteries. Sci. Rep. 4, 07413–07421 (2014).

Balogun, M. S. et al. Binder-free Fe2N nanoparticles on carbon textile with high power density as novel anode for high-performance flexible lithium ion batteries. Nano Energy 11, 348–355 (2015).

Zhang, L., Aboagye, A., Kelkar, A., Lai, C. & Fong, H. A review: carbon nanofibers from electrospun polyacrylonitrile and their applications. J. Mater. Sci. 49, 463–480 (2014).

Zhang, B. et al. Correlation Between Atomic Structure and Electrochemical Performance of Anodes Made from Electrospun Carbon Nanofiber Films. Advanced Energy Materials 4, 9 (2014).

Li, W. et al. Germanium nanoparticles encapsulated in flexible carbon nanofibers as self-supported electrodes for high performance lithium-ion batteries. Nanoscale 6, 4532–4537 (2014).

Zeng, L. et al. A Flexible Porous Carbon Nanofibers-Selenium Cathode with Superior Electrochemical Performance for Both Li-Se and Na-Se Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 5, 1401377–1401386 (2015).

Zhao, B., Cai, R., Jiang, S., Sha, Y. & Shao, Z. Highly flexible self-standing film electrode composed of mesoporous rutile TiO2/C nanofibers for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 85, 636–643 (2012).

Xiong, X. et al. Flexible Membranes of MoS2/C Nanofibers by Electrospinning as Binder-Free Anodes for High-Performance Sodium-Ion Batteries. Sci. Rep. 5, 09254–09259 (2015).

Zhang, G., Wu, H. B., Hoster, H. E. & Lou, X. W. Strongly coupled carbon nanofiber-metal oxide coaxial nanocables with enhanced lithium storage properties. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 302–305 (2014).

Xiao, W., Chen, J. S., Lu, Q. & Lou, X. W. Porous Spheres Assembled from Polythiophene (PTh)-Coated Ultrathin MnO2 Nanosheets with Enhanced Lithium Storage Capabilities. J. Phys. Chem. C 114, 12048–12051 (2010).

Xiao, W., Chen, J. S. & Lou, X. W. Synthesis of octahedral Mn3O4 crystals and their derived Mn3O4-MnO2 heterostructures via oriented growth. Crystengcomm 13, 5685–5687 (2011).

Xia, Y. et al. Green and Facile Fabrication of Hollow Porous MnO/C Microspheres from Microalgaes for Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Nano 7, 7083–7092 (2013).

Sun, Y. M., Hu, X. L., Luo, W., Xia, F. F. & Huang, Y. H. Reconstruction of Conformal Nanoscale MnO on Graphene as a High-Capacity and Long-Life Anode Material for Lithium Ion Batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 23, 2436–2444 (2013).

Jiang, H. et al. Rational Design of MnO/Carbon Nanopeapods with Internal Void Space for High-Rate and Long-Life Li-Ion Batteries. ACS nano 8, 6038–46 (2014).

Chae, C., Kim, J. H., Kim, J. M., Sun, Y. K. & Lee, J. K. Highly reversible conversion-capacity of MnOx-loaded ordered mesoporous carbon nanorods for lithium-ion battery anodes. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 17870–17877 (2012).

Wang, T. Y., Peng, Z., Wang, Y. H., Tang, J. & Zheng, G. F. MnO Nanoparticle@Mesoporous Carbon Composites Grown on Conducting Substrates Featuring High-performance Lithium-ion Battery, Supercapacitor and Sensor. Sci. Rep. 3, 2693–2701 (2013).

Qiu, D. et al. MnO nanoparticles anchored on graphene nanosheets via in situ carbothermal reduction as high-performance anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Mater. Lett. 84, 9–12 (2012).

Hsieh, C. T., Lin, C. Y. & Lin, J. Y. High reversibility of Li intercalation and de-intercalation in MnO-attached graphene anodes for Li-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 56, 8861–8867 (2011).

Zhang, K. J. et al. Synthesis of Nitrogen-Doped MnO/Graphene Nanosheets Hybrid Material for Lithium Ion Batteries. ACS App. Mater. Inter. 4, 658–664 (2012).

Mai, Y. J. et al. MnO/reduced graphene oxide sheet hybrid as an anode for Li-ion batteries with enhanced lithium storage performance. J. Power Sources 216, 201–207 (2012).

Liu, B. et al. Encapsulation of MnO Nanocrystals in Electrospun Carbon Nanofibers as High-Performance Anode Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Sci. Rep. 4, 04229–04234 (2014).

Li, X. et al. MnO@Carbon Core–Shell Nanowires as Stable High-Performance Anodes for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Chemistry—A European Journal 19, 11310–11319 (2013).

Li, X., Zhu, Y., Zhang, X., Liang, J. & Qian, Y. MnO@1-D carbon composites from the precursor C4H4MnO6 and their high-performance in lithium batteries. RSC Advances 3, 10001–10006 (2013).

Sun, X., Xu, Y., Ding, P., Jia, M. & Ceder, G. The composite rods of MnO and multi-walled carbon nanotubes as anode materials for lithium ion batteries. J. Power Sources 244, 690–694 (2013).

Qin, J. et al. MnOx/SWCNT macro-films as flexible binder-free anodes for high-performance Li-ion batteries. Nano Energy 2, 733–741 (2013).

Xu, S. D., Zhu, Y. B., Zhuang, Q. C. & Wu, C. Hydrothermal synthesis of manganese oxides/carbon nanotubes composites as anode materials for lithium ion batteries. Mater. Res. Bull. 48, 3479–3484 (2013).

Du, Y., Zhao, X., Huang, Z., Li, Y. & Zhang, Q. Freestanding composite electrodes of MnOx embedded carbon nanofibers for high-performance supercapacitors. RSC Advances 4, 39087–39094 (2014).

Huang, M. et al. Merging of Kirkendall Growth and Ostwald Ripening: CuO@MnO2 Core-shell Architectures for Asymmetric Supercapacitors. Sci. Rep. 4, 04518–04525 (2014).

Huang, M. et al. Self-Assembly of Mesoporous Nanotubes Assembled from Interwoven Ultrathin Birnessite-type MnO2 Nanosheets for Asymmetric Supercapacitors. Sci. Rep. 4, 03878–03884 (2014).

Inagaki, M., Yang, Y. & Kang, F. Carbon Nanofibers Prepared via Electrospinning. Adv. Mater. 24, 2547–2566 (2012).

Xiao, Y., Wang, X., Wang, W., Zhao, D. & Cao, M. H. Engineering Hybrid between MnO and N-Doped Carbon to Achieve Exceptionally High Capacity for Lithium-Ion Battery Anode. ACS App. Mater. Inter. 6, 2051–2058 (2014).

Sun, Y., Hu, X., Luo, W. & Huang, Y. Porous carbon-modified MnO disks prepared by a microwave-polyol process and their superior lithium-ion storage properties. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 19190–19195 (2012).

Dicastro, V. & Polzonetti, G. XPS study of MnO oxidation. J. Electron Spectrosc. 48, 117–123 (1989).

Young, V. & Zhao, L. Z. XPS study of the electronic structure of dispersed MnO on carbon foil. Chem. Phys. Lett. 102, 455–8 (1983).

Chen, W. M. et al. Superior lithium storage performance in nanoscaled MnO promoted by N-doped carbon webs. Nano Energy 2, 412–418 (2013).

Zhang, L. L., Zhao, X. S., Wei, T. X. & Wang, W. J. Manganese oxide-carbon composite as supercapacitor electrode materials. Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 123, 260–267 (2009).

Sun, B., Chen, Z. X., Kim, H. S., Ahn, H. & Wang, G. X. MnO/C core-shell nanorods as high capacity anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 196, 3346–3349 (2011).

Mao-Sung, W. & Chiang, P. C. J. Electrochemically deposited nanowires of manganese oxide as an anode material for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochem. Commun. 8, 383–8 (2006).

Yu, X. Q. et al. Nanocrystalline MnO thin film anode for lithium ion batteries with low overpotential. Electrochem. Commun. 11, 791–794 (2009).

Zang, J. et al. Reduced Graphene Oxide Supported MnO Nanoparticles with Excellent Lithium Storage Performance. Electrochim. Acta 118, 112–117 (2014).

Xu, G. L. et al. Facile synthesis of porous MnO/C nanotubes as a high capacity anode material for lithium ion batteries. Chem. Commun. 48, 8502–8504 (2012).

Wu, F., Lu, Y., Shao, G., Zeng, F. & Wu, Q. Preparation of polyacrylonitrile/graphene oxide by in situ polymerization. Polym. Int. 61, 1394–1399 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science foundation of China (51403036, 51322204), Shanghai Education Commission “Yangfan” Program (14YF1405300), Shanghai Education development foundation “Chenguang” Program (14S10656), Specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China (SRFDP 20130075120018), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central University (2232014D3-09, WK2060140014) and the External Cooperation Program of BIC, Chinese Academy of Sciences (211134KYSB20130017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Z., Y.W.Z. and Q.H.Z. conceived and designed the experiments. Y.X.D., L.J., Y.Y., S.L.W. and W.H.L. carried out the experimental work. X.Z. wrote the manuscript. Y.W.Z., Y.Y. and Q.H.Z. revised the manuscript. All of the Figures and Table (including those in the supporting information were drawn by the first author, X. Z. The schemes in Figure 1 and Figure 7 were drawn using Microsoft PowerPoint, saved as TIFF. File format and inserted into the manuscript file. All the other curves were drawn using Origin 8.0 Software.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, X., Du, Y., Jin, L. et al. Membranes of MnO Beading in Carbon Nanofibers as Flexible Anodes for High-Performance Lithium-Ion Batteries. Sci Rep 5, 14146 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep14146

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep14146

This article is cited by

-

Two-Step Rapid Synthesis of MnO@C Nanoparticle as a High-Performance Anode for Lithium-Ion Batteries

JOM (2022)

-

3D Interconnected Binder-Free Electrospun MnO@C Nanofibers for Supercapacitor Devices

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Encapsulated MnO in N-doping carbon nanofibers as efficient ORR electrocatalysts

Science China Materials (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.