Abstract

A critical link between amyloid-beta (Aβ) and hypoxia has been demonstrated in in vitro and animal studies but has not yet been proven in humans. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) is a common disorder that is characterized by nocturnal intermittent hypoxaemia. This study sought to examine the association between the chronic intermittent hypoxia and Aβ in OSAS patients. Forty-five cognitively normal OSAS patients and forty-nine age- and gender-matched subjects diagnosed with simple snoring and not OSAS were included in the present study. Serum Aβ40, Aβ42, total tau and phosphorylated tau 181 (P-tau 181) levels were measured using ELISA kits. All subjects were evaluated with nighttime polysomnography and cognitive tests. Compared with the controls, the OSAS patients exhibited significantly higher serum Aβ40, Aβ42 and total Aβ levels and each of these levels was positively correlated with the apnea-hypopnea index, the oxygen desaturation index and the mean and lowest oxyhaemoglobin saturations in the OSAS patients. Moreover, the OSAS patients exhibited strikingly higher serum P-tau 181 levels and these levels were positively correlated with serum Aβ levels. This study suggests that there is an association between chronic intermittent hypoxia and increased Aβ levels, implying that hypoxia may contribute to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common age-related neurodegenerative disorder and is characterized by progressive memory loss and cognitive decline. Senile plaques consisting of abnormally aggregated amyloid-beta (Aβ) peptide are a major pathological hallmark of AD. Aβ has been suggested to play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of this devastating disease1. Many environmental factors are involved in the aetiology of AD and hypoxia is increasingly recognized as being associated with an increased risk of AD2. Recent data have shown that hypoxia is involved in the metabolism of Aβ in animal and cellular models3,4,5. However, the effect of hypoxia on Aβ metabolism in humans remains unknown. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) is a prevalent disorder that is characterized by nocturnal intermittent hypoxaemia that results from episodes of partial or complete upper airway obstruction during sleep6. Thus, OSAS can be viewed as a chronic intermittent hypoxia model in humans. In the present study, we aimed to investigate whether Aβ and phosphorylated tau (P-tau) levels are associated with hypoxia in OSAS patients.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

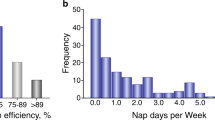

As shown in Table 1, 45 OSAS patients (14 patients with mild, 13 with moderate and 18 with severe OSAS) and 49 age- and gender-matched subjects with simple snoring were included in this study. The controls and OSAS patients were similar regarding educational level (p = 0.595), smoking history (p = 0.834) and body mass index (BMI) (p = 0.146). There were no significant differences in the comorbidities of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease or hyperlipidaemia between the controls and the OSAS group. By definition, the OSAS patients exhibited higher apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) (p < 0.001), arousal index (ArI) (p < 0.001) and oxygen desaturation index (ODI) (p < 0.001) than the controls and the mean oxyhaemoglobin saturation (MSaO2) (p < 0.001) and the lowest oxyhaemoglobin saturation (LSaO2) (p < 0.001) were dramatically lower in the OSAS group. Neither total sleep time (TST) nor sleep efficiency was significantly different between the two groups. The OSAS patients exhibited greater proportions of stages 1 and 2 sleep (p = 0.003) and stage 3 sleep (p = 0.03) and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep (p = 0.006) occupied lower proportions of the sleep time of the OSAS patients.

Serum Aβ levels in the controls and OSAS patients

As presented in Fig. 1, the serum Aβ40 (107.54 ± 65.77 pg/ml vs. 71.58 ± 34.70 pg/ml, p = 0.003), Aβ42 (86.37 ± 61.14 pg/ml vs. 50.91 ± 26.93 pg/ml, p = 0.006) and total Aβ (193.91 ± 122.41 pg/ml vs. 125.35 ± 66.67 pg/ml, p = 0.002) levels were significant higher in the OSAS patients than in the controls.

Correlations of serum Aβ levels with AHI, MSaO2, LSaO2 and ODI in the OSAS patients

Partial correlation analyses were used to investigate the correlations of serum Aβ levels with AHI with adjustments for age, gender, educational level, smoking history, BMI and comorbidities. In the model that included all of the participants, the serum Aβ levels were positively correlated with AHI (Supplementary Table 1). In the model that included only the OSAS patients, the serum Aβ40 (r = 0.333, p = 0.029), Aβ42 (r = 0.313, p = 0.041) and total Aβ (r = 0.336, p = 0.027) levels were also positively correlated with the AHI (Fig. 2). Next, we analysed the associations of the serum Aβ levels with the extent of hypoxia while adjusting for age, gender, educational level, smoking history, BMI, comorbidities and sleep quality. We found that the serum Aβ level was negatively correlated with MSaO2 and LSaO2 and positively correlated with ODI in the model that included all of the subjects (Supplementary Table 1). In the model that included only the OSAS patients, the serum Aβ40 (r = 0.507, p = 0.003), Aβ42 (r = 0.517, p = 0.002) and total Aβ(r = 0.529, p = 0.002) levels were all positively correlated with ODI (Fig. 3A–C). Additionally, the serum Aβ40 (r = −0.429, p = 0.011), Aβ42 (r = −0.358, p = 0.038) and total Aβ levels (r = −0.408, p = 0.017) were all negatively correlated with MSaO2 (Fig. 3D–F) and there was no significant correlation between the serum Aβ level and LSaO2 (Aβ40: r = −0.339, p = 0.050; Aβ42: r = −0.303, p = 0.082; Total Aβ: r = −0.332, p = 0.055; Fig. 3G–I). These data indicated that the Aβ levels were closely related to the extent of hypoxia.

Correlations of the serum Aβ levels with the ODI, mean SaO2 and lowest SaO2 in the patients with OSAS.

(A–C) show the positive correlations of the Aβ40 (r = 0.507, p = 0.003), Aβ42 (r = 0.517, p = 0.002) and total Aβ (r = 0.529, p = 0.002) levels with the ODI. (D–F) show the negative correlations of the Aβ40 (r = −0.429, p = 0.011), Aβ42 (r = −0.358, p = 0.038) and total Aβ (r = −0.408, p = 0.017) levels with the mean SaO2. (G–I) show the negative correlations of the Aβ40 (r = −0.339, p = 0.050), Aβ42 (r = −0.303, p = 0.082) and total Aβ (r = −0.332, p = 0.055) levels with the lowest SaO2.

Serum tau protein levels in the controls and OSAS patients

To investigate whether neuronal injury is induced in the brains of the OSAS patients, we examined the serum total tau and P-tau 181 levels, both of which are biochemical markers of neuronal injury in the brain7,8. No differences in the serum total tau levels between the groups was found (45.40 ± 34.24 pg/ml vs. 40.49 ± 24.61 pg/ml, p = 0.753), but the serum P-tau 181 levels were strikingly increased in the OSAS patients (42.03 ± 21.58 pg/ml vs. 30.56 ± 17.30 pg/ml, p = 0.003; Fig. 4), suggesting that neuronal injuries occurred in the brains of the patients with OSAS. Next, we found that the serum P-tau 181 level was positively correlated with the serum Aβ40 (r = 0.537, p < 0.001), Aβ42 (r = 0.446, p < 0.01) as well as total Aβ (r = 0.511, p < 0.001) levels in the OSAS patients (Fig. 5), suggesting that the OSAS patients with higher Aβ levels may have experienced severe neuronal brain injuries.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to address the serum Aβ and P-tau levels of patients with OSAS. In the present study, we found that compared with the control group, the cognitively normal OSAS patients exhibited significantly higher serum Aβ40, Aβ42 and total Aβ levels and each of these levels was positively correlated with the severity of OSAS and the extent of hypoxia. Moreover, in the OSAS patients, the serum P-tau 181 levels were higher and correlated with the Aβ levels. These findings suggest that hypoxia might facilitate AD-type pathogenesis in humans.

The causal relationship between OSAS and Aβ levels requires further investigation. Previous studies have indicated that OSAS is associated with increased risks of dementia and AD9,10. However, patients with Down syndrome, which is associated with an overproduction of Aβ in the brain, exhibited a high prevalence of OSAS11, suggesting that higher levels of Aβ might cause OSAS. On the other hand, patients with Down syndrome also exhibit unique upper airway anatomic features and increased risks of obesity, gastroesophageal reflux disease, hypothyroidism and generalized physical hypotonia11. These factors might account for the high prevalence of OSAS among patients with Down syndrome. In OSAS, in addition to nocturnal intermittent hypoxia, poor sleep quality is also an aspect of the pathophysiology of the disease that can impair cerebral metabolism, glucose transport and blood-brain barrier functions and even influence Aβ metabolism in the brain12,13,14. The correlations of serum Aβ and P-tau 181 levels with the severity of OSAS and the extent of nocturnal hypoxia remained after adjusting for the confounders of total sleep time, sleep efficiency and sleep stages, suggesting that hypoxia might increase the levels of Aβ and P-tau in OSAS patients.

Aβ is generated through the sequential proteolysis of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) by the enzymes β-secretase (BACE-1) and γ-secretase, whereas Aβ generation can be avoided via a non-amyloidogenic APP processing pathway that is mediated by α-secretase and γ-secretase15. Under conditions of chronic hypoxia, the expression of ADAM10, which is a candidate protein for α-secretase, is decreased in neuronal cells3. Additionally, hypoxia increases the BACE-1 level and the enzymatic activity of this protein by enhancing hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1-α) expression16,17,18, which results in increased Aβ generation in a mouse model of hypoxia5. On the other hand, hypoxia down-regulates the zinc metalloproteinase neprilysin (NEP), one of the most prominent Aβ degrading enzymes19. These studies support the perspective that hypoxia may increase Aβ levels by up-regulating its production and down-regulating its degradation in the brain. Aβ levels in the brain and serum form a dynamic equilibrium. The transport of Aβ from the brain into the peripheral blood has been demonstrated in both animal models and humans20,21 and higher serum Aβ levels might represent higher Aβ burden in the brain. In this regard, our results are consistent with those of previous animal studies that have found that hypoxia is associated with increased Aβ production in the brain5,16. On another hand, increased serum Aβ levels might also originate from the peripheral organs and tissues that express APP and BACE-122, in response to hypoxia in patients with OSAS. It has been suggested that Aβ originating from the periphery can enter the brain and accelerate AD pathogenesis23,24. Moreover, elevated Aβ levels in the serum can reduce its clearance from the brain25.

Tau is a soluble microtubule-associated protein that is localized in the axons of neuron cells in the brain26. Serum phosphorylated tau protein has been suggested to be a biochemical marker of neuronal injury in the brain. In the present study, we found that serum P-tau 181 levels were increased and correlated with the Aβ levels in the OSAS patients. Exposure to hypoxia can induce the hyperphosphorylation of tau in the brains of animals and this hyperphosphorylation is attributable to the activation of kinases that phosphorylate tau (i.e., glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta, cyclin-dependent kinase 5 and mitogen-activated protein kinase) and the inactivation of kinase that dephosphorylate tau (i.e., phosphorylated protein phosphatase 2A)27,28. The increased serum levels of phosphorylated tau observed in OSAS patients may result directly from chronic intermittent hypoxia. Moreover, hypoxia can also promote Aβ-induced tau phosphorylation by calpain29.

The cerebral blood-oxygen content is essential for neural biosynthetic processes. Hypoxia might induce cerebral hypoperfusion and decrease glucose metabolism, which would disrupt neuronal function and accelerate tau hyperphosphorylation10,30. Obviously neuronal loss in the hippocampus has been observed in hypoxia-exposed animals31. Following hypoxia, reoxygenation could affect blood brain barrier (BBB) function and damage small vessels10. Excessive Aβ levels in OSAS could also induce a neurotoxic cascade that leads to neuronal death. Thus, chronic intermittent hypoxia might contribute to neuronal damage and degeneration in the brains of OSAS patients. The increased tau levels observed in the OSAS patients in our study further suggest that repetitive nocturnal hypoxaemia might lead to neuronal degeneration, axonal dysfunction and synaptic loss.

OSAS has been shown to occur more frequently in AD subjects than in cognitively normal older subjects and its severity correlates with cognitive impairment32. Furthermore, OSAS is associated with an increased risk of dementia9,10. These findings imply that OSAS may promote the development of AD. AD occurs more frequently after the age of sixty, while our OSAS patients were relatively young. Giving that AD-type pathology begins 15–20 years before the onset of dementia in sporadic AD33, the elevated Aβ and P-tau levels observed in our patients suggest that OSAS may contribute to the initiation of AD pathogenesis in young patients.

Notably, this study was observational and we were therefore unable to determine the causal relationship between hypoxia and Aβ. Recent studies have shown that the treatment of severe OSAS with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) can slow cognitive decline in patients with AD, which may be due to the correction of intermittent hypoxia34,35,36. However, whether this benefit is associated with decreased Aβ and P-tau levels due to CPAP remains to be investigated. Although we used partial correlations to control for cofounders that included sleep quality, sleep disruption due to chronic fragmentation and restriction may also have affected the results.

In conclusion, this study revealed that increased Aβ levels in the serum are correlated with the severity of chronic intermittent hypoxia in patients with OSAS and the results thus support the link between the detrimental effects of hypoxia and neurodegeneration, suggesting that OSAS may contribute to the pathogenesis of AD. Because OSAS is a prevalent disease that affects a substantial proportion of the elderly, the treatment of OSAS may have potential to prevent the occurrence and progression of AD.

Methods

Study population

A total of 94 subjects with possible OSAS were recruited from the sleep center of the Daping Hospital from September to December of 2014. Among these patients, 45 were ultimately diagnosed with OSAS. Forty-nine age- and gender-matched subjects diagnosed with simple snoring and not OSAS were included as the control group. Subjects were excluded for the following reasons: (1) a family history of dementia; (2) a concomitant neurologic disorder that could potentially affect cognitive function (e.g., severe Parkinson’s disease); (3) severe cardiac, pulmonary, hepatic, or renal diseases or any type of tumour; (4) enduring mental illness (e.g., schizophrenia). Additionally, participants with abnormal cognition according to the Chinese version of the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) were excluded according to protocols have previously been described37. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and International Conference on Harmonisation Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and was approved by Institutional Review Board of Daping Hospital.

OSAS diagnosis and blood sampling

The diagnosis of OSAS was based on the daytime and nocturnal symptoms and nighttime polysomnography (PSG)38, which included records of electroencephalography (EEG), electrooculography (EOG), submental and bilateral tibial muscle electromyography (EMG), electrocardiography (ECG), oxygen saturation, oral and nasal airflow and respiratory effort. TST refers to the time from sleep onset to the end of the final sleep epoch minus the time awake. Sleep efficiency was defined as the ratio of the TST to the time in bed. AHI was defined as the total number of complete cessations (apnea) and partial obstructions (hypopnea) of breathing that occurred by per hour of sleep. Arousal was defined as an interruption of sleep lasting more than 3 seconds. The ArI referred to the total number of arousals divided by the number of hours of sleep. ODI was defined as the number of times per hour of sleep that the blood oxygen level dropped by 3 per cent or more relative to baseline. Based on the AHI, the severity of OSAS was classified as follows: mild OSAS (5 ≤ AHI < 15), moderate OSAS (15 ≤ AHI ≤ 30), or severe OSAS (AHI > 30)38. Demographic data including age, gender, height, weight and educational level, were collected upon admission. BMI was calculated by dividing the weight (kg) by the square of the height (m). Medical histories were collected as per our previous study from the medical records and a formal questionnaire that included current medications37. The data included prior head trauma and surgery, prior gas poisoning, schizophrenia, hypothyroidism, coronary heart diseases, atrial fibrillation, cerebrovascular diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic hepatitis, chronic renal insufficiency, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, Parkinson’s disease and regular use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory and prescription drugs. Fasting blood was sampled between 06:00 and 07:00 to avoid the variation related to possible circadian rhythm effects. The blood samples were centrifuged immediately after drawn and then stored at −80 °C until use. Informed consent was obtained from each participant before the acquisition of the blood sample.

Measurements of serum Aβ and tau levels

Serum Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels were determined using human Aβ enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Covance, Princeton, NJ, USA). Serum total tau and P-tau 181 levels were detected using human tau ELISA kits (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). All of the ELISA measurements were performed according to the manufacturers’ instructions. The samples and standards were measured in duplicate and the means of the duplicates were used for the statistical analyses.

Statistical analysis

The differences in demographic characteristics and serum Aβ levels between the groups were assessed with two-tailed independent t-tests, Mann-Whitney U tests or Chi-squared tests as appropriate. Partial correlation analyses were used to investigate the associations of serum Aβ levels with the AHI, ODI, MSaO2 and LSaO2 values. Spearman correlation analyses were used to examine the correlations between the serum Aβ levels and P-tau 181 levels. The data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). All hypothesis testing was two-sided and p < 0.05 was defined as statistically significant. The computations were performed with SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Bu, X.-L. et al. Serum amyloid-beta levels are increased in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sci. Rep. 5, 13917; doi: 10.1038/srep13917 (2015).

References

Cavallucci, V., D’Amelio, M. & Cecconi, F. Abeta toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurobiol 45, 366–378, 10.1007/s12035-012-8251-3 (2012).

Peers, C. et al. Hypoxia and neurodegeneration. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1177, 169–177, 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05026.x (2009).

Webster, N. J., Green, K. N., Peers, C. & Vaughan, P. F. Altered processing of amyloid precursor protein in the human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y by chronic hypoxia. Journal of neurochemistry 83, 1262–1271 (2002).

Guglielmotto, M. et al. The up-regulation of BACE1 mediated by hypoxia and ischemic injury: role of oxidative stress and HIF1alpha. Journal of neurochemistry 108, 1045–1056, 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05858.x (2009).

Shiota, S. et al. Chronic intermittent hypoxia/reoxygenation facilitate amyloid-beta generation in mice. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease: JAD 37, 325–333, 10.3233/JAD-130419 (2013).

Andreou, G. & Vlachos, F. Effects of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and obstructive sleep apnea on cognitive functions: evidence for a common nature. 2014, 768210, 10.1155/2014/768210 (2014).

Kavalci, C. et al. The value of serum tau protein for the diagnosis of intracranial injury in minor head trauma. The American journal of emergency medicine 25, 391–395, 10.1016/j.ajem.2006.10.008 (2007).

Bitsch, A. et al. Serum tau protein level as a marker of axonal damage in acute ischemic stroke. European neurology 47, 45–51 (2002).

Chang, W. P. et al. Sleep apnea and the risk of dementia: a population-based 5-year follow-up study in Taiwan. PloS one 8, e78655, 10.1371/journal.pone.0078655 (2013).

Pan, W. & Kastin, A. J. Can sleep apnea cause Alzheimer’s disease? Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews 47, 656–669, 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.10.019 (2014).

Lal, C., White, D. R., Joseph, J. E., van Bakergem, K. & LaRosa, A. Sleep-disordered breathing in Down syndrome. Chest 147, 570–579, 10.1378/chest.14-0266 (2015).

Ju, Y. E. et al. Sleep quality and preclinical Alzheimer disease. JAMA neurology 70, 587–593, 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.2334 (2013).

He, J. et al. Sleep restriction impairs blood-brain barrier function. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 34, 14697–14706, 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2111-14.2014 (2014).

Ju, Y. E., Lucey, B. P. & Holtzman, D. M. Sleep and Alzheimer disease pathology–a bidirectional relationship. Nature reviews. Neurology 10, 115–119, 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.269 (2014).

Rajendran, L. & Annaert, W. Membrane trafficking pathways in Alzheimer’s disease. Traffic (Copenhagen, Denmark) 13, 759–770, 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2012.01332.x (2012).

Sun, X. et al. Hypoxia facilitates Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis by up-regulating BACE1 gene expression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103, 18727–18732, 10.1073/pnas.0606298103 (2006).

Li, L. et al. Hypoxia increases Abeta generation by altering beta- and gamma-cleavage of APP. Neurobiology of aging 30, 1091–1098, 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.10.011 (2009).

Zhang, X. et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha (HIF-1alpha)-mediated hypoxia increases BACE1 expression and beta-amyloid generation. The Journal of biological chemistry 282, 10873–10880, 10.1074/jbc.M608856200 (2007).

Fisk, L., Nalivaeva, N. N., Boyle, J. P., Peers, C. S. & Turner, A. J. Effects of hypoxia and oxidative stress on expression of neprilysin in human neuroblastoma cells and rat cortical neurones and astrocytes. Neurochemical research 32, 1741–1748, 10.1007/s11064-007-9349-2 (2007).

Roberts, K. F. et al. Amyloid-beta efflux from the central nervous system into the plasma. Annals of neurology 76, 837–844, 10.1002/ana.24270 (2014).

Ghersi-Egea, J. F. et al. Fate of cerebrospinal fluid-borne amyloid beta-peptide: rapid clearance into blood and appreciable accumulation by cerebral arteries. Journal of neurochemistry 67, 880–883 (1996).

Nalivaeva, N. N. & Turner, A. J. The amyloid precursor protein: a biochemical enigma in brain development, function and disease. FEBS letters 587, 2046–2054, 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.05.010 (2013).

Eisele, Y. S. et al. Peripherally applied Abeta-containing inoculates induce cerebral beta-amyloidosis. Science 330, 980–982, 10.1126/science.1194516 (2010).

Sutcliffe, J. G., Hedlund, P. B., Thomas, E. A., Bloom, F. E. & Hilbush, B. S. Peripheral reduction of beta-amyloid is sufficient to reduce brain beta-amyloid: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of neuroscience research 89, 808–814, 10.1002/jnr.22603 (2011).

Marques, M. A. et al. Peripheral amyloid-beta levels regulate amyloid-beta clearance from the central nervous system. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease: JAD 16, 325–329, 10.3233/JAD-2009-0964 (2009).

Binder, L. I., Frankfurter, A. & Rebhun, L. I. The distribution of tau in the mammalian central nervous system. The Journal of cell biology 101, 1371–1378 (1985).

Chen, G. J., Xu, J., Lahousse, S. A., Caggiano, N. L. & de la Monte, S. M. Transient hypoxia causes Alzheimer-type molecular and biochemical abnormalities in cortical neurons: potential strategies for neuroprotection. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease: JAD 5, 209–228 (2003).

Zhang, C. E. et al. Hypoxia-induced tau phosphorylation and memory deficit in rats. Neuro-degenerative diseases 14, 107–116, 10.1159/000362239 (2014).

Gao, L., Tian, S., Gao, H. & Xu, Y. Hypoxia increases Abeta-induced tau phosphorylation by calpain and promotes behavioral consequences in AD transgenic mice. Journal of molecular neuroscience: MN 51, 138–147, 10.1007/s12031-013-9966-y (2013).

Daulatzai, M. A. Death by a thousand cuts in Alzheimer’s disease: hypoxia–the prodrome. Neurotoxicity research 24, 216–243, 10.1007/s12640-013-9379-2 (2013).

Maiti, P., Singh, S. B., Mallick, B., Muthuraju, S. & Ilavazhagan, G. High altitude memory impairment is due to neuronal apoptosis in hippocampus, cortex and striatum. J Chem Neuroanat 36, 227–238, 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2008.07.003 (2008).

Janssens, J. P., Pautex, S., Hilleret, H. & Michel, J. P. Sleep disordered breathing in the elderly. Aging (Milan, Italy) 12, 417–429 (2000).

Jack, C. R. Jr. & Holtzman, D. M. Biomarker modeling of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 80, 1347–1358, 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.12.003 (2013).

Ancoli-Israel, S. et al. Cognitive effects of treating obstructive sleep apnea in Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized controlled study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 56, 2076–2081, 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01934.x (2008).

Troussiere, A. C. et al. Treatment of sleep apnea syndrome decreases cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery and psychiatry 85, 1405–1408, 10.1136/jnnp-2013-307544 (2014).

Osorio, R. S. et al. Sleep-disordered breathing advances cognitive decline in the elderly. Neurology, 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001566 (2015).

Li, J. et al. Vascular risk factors promote conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer disease. Neurology 76, 1485–1491, 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318217e7a4 (2011).

Qureshi, A. & Ballard, R. D. Obstructive sleep apnea. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 112, 643–651; quiz 652, 10.1016/s0091 (2003).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81270423 and 81471296).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.B. and Y.W. conceived and designed the study; X.B., Y.L., Q.W., S.J. and F.Z. performed the study; X.B., Y.L., X.Y., D.G. and J.C. analyzed the data; all the authors (X.B., Y.L., Q.W., S.J., F.Z., X.Y., D.G., J.C. and Y.W.) wrote the article. All authors (X.B., Y.L., Q.W., S.J., F.Z., X.Y., D.G., J.C. and Y.W.) have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Bu, XL., Liu, YH., Wang, QH. et al. Serum amyloid-beta levels are increased in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sci Rep 5, 13917 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep13917

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep13917

This article is cited by

-

Chronic Sustained Hypoxia Leads to Brainstem Tauopathy and Declines the Power of Rhythms in the Ventrolateral Medulla: Shedding Light on a Possible Mechanism

Molecular Neurobiology (2023)

-

Evidence of plasma biomarkers indicating high risk of dementia in cognitively normal subjects

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Letter to the editor regarding “Biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease in severe obstructive sleep apnea–hypopnea syndrome in the Chinese population”

European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology (2022)

-

Cognitive impairment caused by hypoxia: from clinical evidences to molecular mechanisms

Metabolic Brain Disease (2022)

-

Critical thinking on amyloid-beta-targeted therapy: challenges and perspectives

Science China Life Sciences (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.