Abstract

Despite a high similarity with homologous protein families, only few proteins trigger an allergic immune response with characteristic TH2 polarization. This puzzling observation is illustrated by the major birch pollen allergen Bet v 1a and its hypoallergenic protein isoforms, e.g., Bet v 1d. Given the key role of proteolytic processing in antigen presentation and T cell polarization, we investigated the recognition of Bet v 1 isoforms by the relevant protease cathepsin S. We found that at moderately acidic pH values Bet v 1a bound to cathepsin S with significantly lower affinity and was more slowly cleaved than its hypoallergenic isoform Bet v 1d. Only at pH values ≤4.5 the known proteolytic cleavage sites in Bet v 1a became accessible, resulting in a strong increase in affinity towards cathepsin S. Antigen processing and class II MHC loading occurs at moderately acidic compartments where processing of Bet v 1a and Bet v 1d differs distinctly. This difference translates into low and high density class II MHC loading and subsequently in TH2 and TH1 polarization, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Allergic reactions to proteins of the pathogenesis-related protein family number 10 (PR-10) are mainly related to birch pollen. Additionally more than 70% of patients have pollen-related food allergy1. The cross-reactive plant proteins have up to 75% sequence similarity and all known structures of these cross-reactive proteins share a highly conserved fold2. Nevertheless only Bet v 1, the major allergen from birch pollen, is considered to have the capacity to trigger the initial allergic response3,4. The comparison between isolated and recombinant Bet v 1 led to the discovery of thirteen different isoforms (1.0101 to 1.3001, formerly a-n) with more than 95% sequence identity. Mass spectrometry revealed that Bet v 1a (1.0101) represents at least 50% of the total mass of pollen Bet v 15 while Bet v 1d (1.0401) is present with approximately 10%6. Despite the high sequential and structural identity, allergen isoforms can differ drastically in their allergenic potential. Only Bet v 1a induces high IgE antibody production, while Bet v 1d triggers IgG4 expression. Consequently Bet v 1a acts as the sensitizing allergen whereas the hypoallergenic Bet v 1d mainly induces a protective immune response7. This might be a general feature of allergens, as hypoallergenic variants were identified in several species8. The prerequisite for IgE production is the polarization of naïve T cells to TH2 cells, which subsequently release cytokines to stimulate IgE production in B cells. It was shown that antigen density on the surface of antigen presenting cells (APCs) is one of the important factors that influence the fate of a naïve CD4+ T cell. High concentrations of class II MHC loaded with antigen-derived peptides promote TH1-like responses, whereas a lower density supports TH2 cell differentiation9. Antigenic peptides are generated by endolysosomal proteases, mostly papain-like cysteine cathepsins S, L, B and V, but also by aspartate cathepsins D and E10. Cathepsin L is mostly found in the thymus where it plays important roles in the antigen processing and presentation with relevance to tolerance induction, but to a lesser extent in dendritic cells (DCs). In contrast, cathepsin S is predominantly expressed in professional APCs, namely DCs and B cells11. Using activity based probes it was shown that antigens are selectively targeted to cathepsin S in DCs and are only poorly recognized by other cathepsins12. Moreover, in a comparative study of cathepsin B, C, L and S cathepsin L was found to be most effective under lysosomal conditions, albeit also active under endosomal conditions13. By contrast, cathepsin S activity was shown to be much stronger in the endosome than in the lysosome14. This suggests that cathepsin S is the major protease in early recognition and relevant for the cleavage of antigens. Indeed, the majority of Bet v 1 antigenic peptides, which were produced by extracts of endolysosomal proteases, could be generated by cathepsin S alone15.

We therefore used Bet v 1a and Bet v 1d as sensitizing and hypoallergenic model allergens to study differences in the recognition by cathepsin S. The major aim of this study was to find out why hypoallergenic isoforms differ drastically in their immune response, although they have almost identical sequences. Structural dynamics and flexibility can be different between highly similar isoforms, which cannot be derived from crystal structures16. In this work we wanted to analyze if structural flexibility is a key difference between hypoallergenic and sensitizing allergens.

Results

Early Bet v 1 cleavage sites are not accessible to proteases

The early endosomal cleavage sites in Bet v 1a have been identified and replicated in an in vitro cathepsin S cleavage assay15. Surprisingly, detailed analysis of the Bet v 1a structure revealed that none of them is easily accessible to the active site of proteases, as they are mostly located in secondary structure elements (Fig. 1a). Additionally, crystal structures of hypoallergenic and sensitizing Bet v 1 isoforms are remarkably similar (Fig. 1b). This counterintuitive observation prompted us to investigate whether and to which extent cathepsin S could recognize Bet v 1a and whether the comparison of the cathepsin S—Bet v 1d recognition could reveal a molecular link to their different allergenic properties.

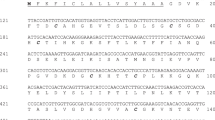

Bet v 1 cleavage sites are cryptic and require reordering for protease access.

(a) Initial recognition sites are harboured within secondary structures. The initial recognition sites15 were mapped into the crystal structure of Bet v 1a (PDB: 4A88). Cleavage sites are indicated with black arrows. The sites are embedded within α-helices (sites I, IV), a 1–4 tight turn (site II), or a β-sheet (site III) (b) Crystal structures of sensitizing Bet v 1a (PDB 4A88, dark grey) and hypoallergenic Bet v 1l (PDB 1FM432, green) share a highly conserved fold. Cathepsin S recognition sites are located in stabilized regions. The structure-based alignment was performed with topmatch33 (c) Differences in sequence between Bet v 1a and Bet v 1d (red letters) do not coincide with cathepsin S cleavage sites. The secondary structure is indicated below each row. Coloured backgrounds represent the protease recognition sites from the non-primed site P3 to the primed site P3’. The scissile bond is marked by a black arrow. The alignment was created with ClustralW34 and modified with Aline35.

Binding of Bet v 1 isoforms to immobilized cathepsin S revealed low affinity sites in Bet v 1a, but high affinity sites in Bet v 1d

To study the binding of allergen isoforms to cathepsin S, the C25A inactivated protease was immobilized on a sam5 chip. Its structural integrity was confirmed by high affinity cystatin C binding, an endogenous inhibitor of cathepsin S (Fig. S1). The overall affinity of the hypoallergenic isoform Bet v 1d to cathepsin S was approximately four times higher compared to the sensitizing allergen Bet v 1a (Fig. 2). This finding suggested to us that the substrate recognition sites are hardly accessible in Bet v 1a, consistent with our structural analysis (Fig. 1a). By contrast, the recognition sites must be dynamically more accessible in Bet v 1d.

Binding affinity of cathepsin S is four times higher towards Bet v 1d than Bet v 1a.

In trans activated C25A-cathepsin S was immobilized on a sam®5BLUE biosensor chip. Its binding to Bet v 1a and Bet v 1d was measured at pH 6.7 in a concentration range from 10 to 100 μM. The 4–5 fold increased phase shift in Bet v 1d as compared to Bet v 1a reflects their differences in binding. KD app for Bet v 1a and Bet v 1d were calculated to be 21.5 ± 9.3 μM and 5.4 ± 0.8 μM respectively. The sensograms of 2 independent measurements are shown for Bet v 1a (top) and Bet v 1d (bottom) binding. The calculated dissociation constant KD app represents an average affinity of initial Bet v 1 recognition sites (I to IV). Correspondingly, the enlarged view shows biphasic binding for Bet v 1a at low concentrations.

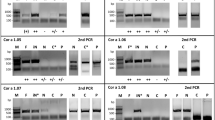

To test this interpretation, we compared the degradation kinetics of Bet v 1a and Bet v 1d by active wild type cathepsin S. We found that the Bet v 1a degradation was significantly retarded as compared to more rapidly digested Bet v 1d (Fig. 3), reflecting their differences in binding to cathepsin S.

Degradation of Bet v 1a by active wild type cathepsin S was significantly slower as compared to more rapidly digested Bet v 1d. A ratio of 1:10 protease to substrate was incubated at 37 °C at pH 5.

Samples were taken after 0, 0.5, 1, 3, 5 and 24 h. In a control experiment Bet v 1 was incubated for 24 h at 37 °C at pH 5 without addition of cathepsin S. Bet v 1d degradation after 1h corresponded to Bet v 1a degradation after 24 h.

As illustrated in Fig. 1, Bet v 1 is processed by cathepsin S at several distinct sites. Therefore the here measured affinities should represent an average of the initial recognition sites. Consistent herewith, the binding sensograms typically feature a biphasic association curve with a relatively sharp initial increase in binding followed by a shallow secondary phase. This observation is suggesting that different Bet v 1 recognition sites differ in their affinity towards cathepsin S.

Bet v 1a and Bet v 1d share a high sequence identity of ~95%, i.e. their amino acid sequences differ only at 7 positions. Notably, these point mutations do not overlap with the initial cathepsin S recognition sites, implying that they are at structurally different positions on Bet v 1 (Fig. 1c). Also the crystal structures of hypoallergenic and sensitizing isoforms are virtually identical (Fig. 1b). Therefore, the observed differences in binding affinities and cleavage kinetics of the two Bet v 1 isoforms cannot be explained by the comparison of their sequence or crystal structures.

We therefore postulated that both Bet v 1 isoforms undergo conformational transitions preceding or upon complex formation with cathepsin S, rendering the cleavage sites accessible for proteolysis. The observed differences in cathepsin S binding and processing could then be explained by the higher or lower energetic barrier that needs to be overcome by Bet v 1a or Bet v 1d, respectively. Indeed, minimal changes in the amino acid sequence can have a significant impact on fold stability and flexibility17.

Differences in the fold flexibility of Bet v 1 isoforms relate to their different affinities towards cathepsin S

To test the relevance of the substrates’ fold stability and flexibility for cathepsin S binding, we compared the binding affinities of native and thermally destabilized Bet v 1 molecules. To obtain structurally destabilized Bet v 1, the protein was shortly incubated at 60 °C, close to its melting point of Tm = 64 °C18. Only soluble, monodisperse fractions of thermally destabilized Bet v 1 were used for cathepsin S binding experiments. We found that the affinities of the Bet v 1 isoforms to cathepsin S converged under destabilizing conditions (Fig. 4). This convergence is due to a five-fold reduction in affinity of Bet v 1d. This change in affinities indicates that the substrate’s fold is indeed important for recognition by the enzyme cathepsin S. The fold encodes an isoform-specific protein dynamics that is critical for the higher affinity of Bet v 1d than that of Bet v 1a.

Convergence of binding affinities upon structural destabilization.

Whereas Bet v 1a maintained its binding affinity towards cathepsin S, the affinity of Bet v 1d significantly decreased upon thermal destabilization, resulting in an effective convergence of the binding affinities of both isoforms. Binding affinities to immobilized cathepsin S were measured at pH 6.7. Affinities of heat-treated Bet v 1a and Bet v 1d were measured after spin filtration with the same concentrations. Bars represent the mean affinity of 5 measurements; errors show standard deviations.

Acidic pH is necessary for Bet v 1a, but not Bet v 1d recognition

Since the fold stability of a protein is dependent on several factors such as pH we next analyzed the effect of different pH values on cathepsin S–Bet v 1 complex formation. This factor was especially interesting, since pH is important in the maturation of the endosome. Interestingly, we found that Bet v 1a binding to cathepsin S is pH dependent: pH ≤ 4.5 resulted in a significant increase in binding as compared to neutral pH. Importantly, the recognition of Bet v 1a by cathepsin S at neutral and slightly acidic pH was very low (Fig. 5a). As shown previously, the Bet v 1a affinity towards cathepsin S depended on its fold and the encoded dynamics. Therefore, we conclude that the fold encoded dynamics of Bet v 1a is similarly pH dependent. In contrast, Bet v 1d was bound already at neutral pH, with steadily, but less pronounced increase in binding with lowering pH (Fig. 5b). Furthermore, the binding curves of Bet v 1a and Bet v 1d converge at acidic pH values, indicating a comparable dynamics of both isoforms.

Binding to cathepsin S is pH-dependent and differs significantly between Bet v 1 isoforms.

(a) Binding of Bet v 1a (10 μM) to immobilized cathepsin S was weak at near neutral pH values (8.5, 7.4 and 6.7). Only at acidic pH (pH ≤ 5.5) binding affinity increased significantly. (b) By contrast, binding affinity of Bet v 1d (10 μM) to cathepsin S increased continuously with decreasing pH, except for pH 7.4 where weakest binding was observed. Results for 2 independent measurements are shown.

Discussion

Hyperallergenic and hypoallergenic isoforms of the birch pollen allergen Bet v 1 spotlight a key problem in allergology, namely the causal linkage of molecular properties with their sensitizing potential. In the current study we found low affinity binding of Bet v 1a, but high affinity binding of Bet v 1d, to cathepsin S; the latter protease is critical in its antigen processing15. In line with these findings, cathepsin S processed Bet v 1a significantly more slowly than Bet v 1d. Given their high sequential and structural similarity, these findings are intriguing and could be explained by differences in the dynamics of the Bet v 1 isoforms. Importantly, acidic pH ≤ 4.5 triggered the conformational changes that resulted in significantly faster binding to cathepsin S, which was then comparable to Bet v 1d. The underlying molecular mechanism most likely is a better accessibility of the Bet v 1a recognition sites due to increased structural flexibility at low pH.

The pH value is a key factor in endosomal processing and endocytosed proteins experience an increased acidification from pH 7 to pH 4 during endosomal maturation. APCs have developed strategies to prevent the rapid acidification of endosomal compartments. This allows proteins to remain intact for a longer period of time, which is a prerequisite for the presentation pathway of antigens19,20 (Fig. 6). Consequently a continuous supply of intact protein allows persistent generation of peptides suitable for presentation (>12 aa). Our results show that the non-sensitizing Bet v 1d will be preferentially processed in the late endosome (LE) at slightly acidic pH (≥5.521), resulting in antigenic peptides for class II MHC presentation; by contrast, only few antigenic peptides will result from Bet v 1a at this milieu. Cathepsin S is, unlike many other lysosomal cysteine proteases, stable and active under a broad pH range, including the class II MHC presentation compartment22. Indeed relatively high levels of cathepsin S activity were detected in the early endosomes (EEs) of antigen presenting cells, especially of dendritic cells, less in macrophages23. Class II MHC is synthesized and assembled in the endoplasmatic reticulum (ER), directed via the invariant chain li either directly to EEs or more commonly to the plasma membrane, from where it is internalized again by endocytosis24. Newly synthesized class II MHC-li complexes are processed mainly by cathepsin S, before peptide loading (reviewed in25). Of similar importance, class II MHC loaded complexes reside primarily in late endosomes (LEs)26. By contrast, mature lysosomes at more acidic pH values contain only little class II MHC and are unlikely to generate any functional peptide loaded complex27.

pH-dependent proteolytic resistance of Bet v 1a and 1d selects for the protein degradation and antigen presentation pathway, respectively.

Bet v 1a mostly escapes the antigen presentation pathway, because its cleavage sites are cryptic at pH ≥ 5.5; therefore the majority of Bet v 1a ends up in the degradation pathway. By contrast, Bet v 1d is readily processed in the antigen presentation pathway with pH ≥ 5.5. Consequently, large amounts of Bet v 1d-derived peptides will be loaded and presented on class II MHC, explaining the protective TH1 response. The large amounts of endocytosed Bet v 1a allergen together with its low proteolytic processing at pH ≥ 5.5 warrant a continuous supply of Bet v 1a peptides for presentation albeit at low concentration, thus explaining its allergic TH2 response. pH values for the early endosome (EE, pH 6.8-5.5), the late endosome (LE, pH 5.5-5) and the lysosome (pH 5-4) are approximate values as reported in the literature21,36,37.

In conclusion, hypoallergenic variants such as Bet v 1d are largely processed within the LE by cathepsin S, with a preferential class II MHC loading with Bet v 1d-derived peptides. The resulting high density of Bet v 1d-mediated synapses of APCs with naïve T-cells induces their polarization to TH1 cells with a protective immune response. In contrast, the Bet v 1a-mediated APC—T cell synapses are sparse and consequently induce the polarization of T cells into TH2 with an allergic immune response. Large amounts of endocytosed Bet v 1a are necessary to maintain the continuous supply of loaded class II MHC complexes at low dose, critical for TH2 polarization28. The majority of Bet v 1a protein will be completely recycled along the degradation pathway in the LE and the lysosome at acidic conditions (pH ≤ 4.5; Fig. 6). Finally, the here provided concept of pH-dependent proteolytic resistance of allergen offers new treatment options for allergic patients. The in vitro screening for and identification of orally available low molecular weight compounds that expose the cryptic proteolytic recognition sites in allergens have the potential to induce an immune protection, similar like specific immune therapy.

Methods

Cloning, expression and purification of cathepsin S

Human procathepsin S cDNA clone BC002642 was obtained from GeneCopoeia (Rockville, US). For subcloning of expression constructs Escherichia coli strain XL2 Blue (Stratagene, La Jolla, USA) was used. To obtain glycosylated protein, procathepsin S was expressed in the Leishmania tarentolae system (LEXSY; Jena Bioscience, Germany). The encoding DNA was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (Eppendorf Mastercycler ep gradient thermal cycler) with human cathepsin S full-length cDNA clone BC002642 as template and primers containing an XbaI restriction site and six codons for histidine (CCTCTCTAGAGCACCACCATCACCACCACGTGGCACAGTTGCATAAAGATCCTA CCCTG) and a NotI restriction site (GAGGGCGGCCGCTCACTAGATTTCTGGGTAAG). The PCR product was cloned into the pLEXSY-sat2 vector using the XbaI and NotI restriction sites. Point mutations C25A and S21C were introduced with ‘Round-the-horn’ site-directed mutagenesis29. All expression constructs contain an N-terminal signal sequence for secretory expression, followed by an N-terminal His6-tag for purification, which remains with the propeptide after autoactivation. The identity of expression constructs was confirmed by DNA sequencing. Stable transfection of expression constructs into the LEXSY P10 host strain was achieved by electroporation and subsequent selection of positive clones was performed via addition of nourseothricin (Jena Bioscience). Cells were grown at 26 °C in BHI medium (Jena Bioscience) supplemented with 5 μg/ml hemin, 50 units/ml penicillin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin (Carl Roth). Large-scale expression was carried out in 500 ml shaking flasks at 26 °C until OD600≈3 was reached. Recombinant procathepsin S was purified from the LEXSY supernatant via Ni–NTA superflow resin (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Eluates in 400 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 300–500 mM imidazole were concentrated using Amicon Ultra centrifugal filter units (3 kDa molecular-weight cutoff, Millipore). For long-term storage of procathepsin S the buffer was changed to 20 mM Tris pH 8, 20 mM NaCl, 5 mM DTT using NAP-5 desalting columns (GE Healthcare). For autoactivation wild-type procathepsin S was incubated in a buffer composed of 5 mM EDTA 2.5 mM DTT and 100 mM sodium acetate pH 4.0 for up to 24 h at 37 °C. To activate the C25A active site dead mutant, the buffer was set to 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM sodium acetate pH 5 and human legumain produced as described in30 was added at a ratio of ≈1:500 and incubated at 30 °C for at least 2 h. To remove uncleaved procathepsin S and the non-covalently bound prodomain, the pH of the buffer was raised to pH 8 and the samples were again applied to Ni-NTA columns. The flow through contained mature cathepsin S.

Expression and purification of Bet v 1a and 1d

Recombinant Bet v 1a and Bet v 1d were expressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3) as non-classical inclusion bodies. The expression construct was cloned into a modified pET-28b vector, lacking the N-terminal His6-tag. Cells were grown in 600 ml LB medium supplemented with 20 μg/ml kanamycin at 37 °C to an OD600 of 1.0. Expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG and cells were harvested after 4 h. Purification of the non-tagged Bet v 1 was performed with acidic salt precipitation, hydrophobic interaction (phenyl-sepharose) and anion exchange (diethylaminoethano–sepharose) chromatography as previously published31. Additionally size exclusion chromatography was applied as a final purification step, using a Superdex75 column (GE Healthcare). Purified Bet v 1 was stored in 20 mM imidazole, pH 7.4 and 50 mM NaCl at −80 °C.

Proteolytic processing assay

Bet v 1a and Bet v 1d (c = 0.25 mg/ml) were dialyzed against a buffer composed of 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT and 10 mM sodium acetate pH 5 and spin-filtrated before protease digestion. 120 μl of Bet v 1 were mixed with 25 μl activated cathepsin S (0.1 mg/ml in 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT and 10 mM sodium acetate pH 5) and incubated at 37 °C. This corresponds to a ratio of 1:10 protease to substrate. 20 μl samples were taken after 0, 0.5, 1, 3, 5 and 24 h. In a control experiment Bet v 1 supplemented with 25 μl buffer without addition of cathepsin S was incubated for 24 h at 37 °C.

Interaction studies using SAW-technology (Surface Acoustic Waves)

The sam®5BLUE biosensor instrument (nanotemper, Munich, Germany) was used to test the interaction of different Bet v 1 isoforms with cathepsin S. In trans activated C25A-cathepsin S was coupled to the surface of a sam short-chain COOH sensor chip. The protein was incubated in a buffer composed of 20 mM sodium acetate pH 5.0, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA and 0.5 mM DTT. 240 μl of a 500 nM cathepsin S solution were injected to the chip, which was activated with a 1:1 mixture of 400 mM 1-[3-(dimethylamino)propyl]-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) and 100 mM N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS). Sequential injection of increasing ligand concentrations (Bet v 1 isoforms) were performed to calculate the affinity constant KD. Freshly spin-filtered Bet v 1 samples were applied at concentrations of 5 μM to 100 μM in a buffer composed of 20 mM imidazole pH 6.7, 50 mM NaCl. For the measurement of heat-destabilized Bet v 1a and 1d samples, protein concentrations of 10 to 100 μM and 2.5 to 40 μM were used, respectively. The coated chip was equilibrated in the same buffer. Between each injection residual ligand was removed with regeneration buffer (10 mM citric acid pH 3.0). Experiments were repeated with two individually coated chips. SAW phase changes were recorded and used to calculate the affinities based on pseudo-first order kinetics (kobs), from which the apparent dissociation constants KD app were determined by linear regression. Fitmaster, a customized add-on for Origin (OriginLab, Northampton, MA) was used to fit the raw data. Best fitting was obtained when an incomplete regeneration (uncoupled kdiss) was chosen as mathematical model. To test the effect of pH on Bet v 1 binding 10 μl of each isoform (a and d) were dialyzed against five different buffers (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.5, 20 mM PBS pH 7.4, 20 mM imidazole pH 6.7, 20 mM acetic acid pH 5.5, 20 mM acetic acid pH 4.5, all except PBS were supplemented with 50 mM NaCl). The chip was equilibrated with the respective buffer prior to injection of Bet v 1.

Induction and control of destabilized Bet v 1

To destabilize the fold, a 100 μM stock solution of Bet v 1 was incubated for 10 min at 60 °C, close to, but lower than the melting point (Tm = 64 °C; quantitative precipitation occurred after 15 to 20 min). Potential high molecular weight aggregates were removed by spin filtration. The concentration before and after filtration was controlled by measuring the absorption at 280 nm wavelength. To test monodispersity of heat-treated Bet v 1, 70 μL of a 100 μM stock solution were compared with untreated Bet v 1 samples by dynamic light scattering (Fig. S2). Only monomeric Bet v 1 was used to study the binding to cathepsin S.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Freier, R. et al. Protease recognition sites in Bet v 1a are cryptic, explaining its slow processing relevant to its allergenicity. Sci. Rep. 5, 12707; doi: 10.1038/srep12707 (2015).

References

Bohle, B. The impact of pollen-related food allergens on pollen allergy. Allergy 62, 3–10, 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01258.x (2007).

Neudecker, P. et al. Mutational epitope analysis of Pru av 1 and Api g 1, the major allergens of cherry (Prunus avium) and celery (Apium graveolens): correlating IgE reactivity with three-dimensional structure. The Biochemical journal 376, 97–107, 10.1042/BJ20031057 (2003).

Mari, A., Wallner, M. & Ferreira, F. Fagales pollen sensitization in a birch-free area: a respiratory cohort survey using Fagales pollen extracts and birch recombinant allergens (rBet v 1, rBet v 2, rBet v 4). Clinical & Experimental Allergy 33, 1419–1428, 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2003.01773.x (2003).

Hauser, M. et al. Bet v 1-like pollen allergens of multiple Fagales species can sensitize atopic individuals. Clinical and experimental allergy : journal of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology 41, 1804–1814, 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03866.x (2011).

Swoboda, I. et al. Isoforms of Bet v 1, the Major Birch Pollen Allergen, Analyzed by Liquid Chromatography, Mass Spectrometry and cDNA Cloning. Journal of Biological Chemistry 270, 2607–2613, 10.1074/jbc.270.6.2607 (1995).

Ferreira, F. et al. Dissection of immunoglobulin E and T lymphocyte reactivity of isoforms of the major birch pollen allergen Bet v 1: potential use of hypoallergenic isoforms for immunotherapy. The Journal of Experimental Medicine 183, 599–609, 10.1084/jem.183.2.599 (1996).

Wagner, S. et al. Naturally occurring hypoallergenic Bet v 1 isoforms fail to induce IgE responses in individuals with birch pollen allergy. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 121, 246–252, 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.08.006 (2008).

Reuter, A. et al. Novel isoforms of Pru av 1 with diverging immunoglobulin E binding properties identified by a synergistic combination of molecular biology and proteomics. Proteomics 5, 282–289, 10.1002/pmic.200400874 (2005).

Constant, S., Pfeiffer, C., Woodard, A., Pasqualini, T. & Bottomly, K. Extent of T-Cell Receptor Ligation Can Determine the Functional-Differentiation of Naive Cd4(+) T-Cells. Journal of Experimental Medicine 182, 1591–1596, 10.1084/jem.182.5.1591 (1995).

Conus, S. & Simon, H. U. Cathepsins and their involvement in immune responses. Swiss medical weekly 140, w13042, 10.4414/smw.2010.13042 (2010).

Hsing, L. C. & Rudensky, A. Y. The lysosomal cysteine proteases in MHC class II antigen presentation. Immunological reviews 207, 229–241, 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00310.x (2005).

Reich, M. et al. Endocytosis targets exogenous material selectively to cathepsin S in live human dendritic cells, while cell-penetrating peptides mediate nonselective transport to cysteine cathepsins. Journal of leukocyte biology 81, 990–1001, 10.1189/jlb.1006600 (2007).

Jordans, S. et al. Monitoring compartment-specific substrate cleavage by cathepsins B, K, L and S at physiological pH and redox conditions. BMC biochemistry 10, 23, 10.1186/1471-2091-10-23 (2009).

Lutzner, N. & Kalbacher, H. Quantifying Cathepsin S Activity in Antigen Presenting Cells Using a Novel Specific Substrate. Journal of Biological Chemistry 283, 36185–36194, 10.1074/jbc.M806500200 (2008).

Egger, M. et al. Assessing protein immunogenicity with a dendritic cell line-derived endolysosomal degradome. PLoS One 6, e17278, 10.1371/journal.pone.0017278 (2011).

Magler, I., Nüss, D., Hauser, M., Ferreira, F. & Brandstetter, H. Molecular metamorphosis in polcalcin allergens by EF-hand rearrangements and domain swapping. FEBS Journal 277, 2598–2610, 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07671.x (2010).

Cooper, D. R. et al. Protein crystallization by surface entropy reduction: optimization of the SER strategy. Acta Crystallogr D 63, 636–645, 10.1107/S0907444907010931 (2007).

Asam, C. et al. Bet v 1—a Trojan horse for small ligands boosting allergic sensitization? Clin Exp Allergy 44, 1083–1093, 10.1111/cea.12361 (2014).

Delamarre, L., Pack, M., Chang, H., Mellman, I. & Trombetta, E. S. Differential lysosomal proteolysis in antigen-presenting cells determines antigen fate. Science (New York, N.Y.) 307, 1630–1634, 10.1126/science.1108003 (2005).

Savina, A. et al. NOX2 Controls Phagosomal pH to Regulate Antigen Processing during Crosspresentation by Dendritic Cells. Cell 126, 205–218, 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.035 (2006).

Compeer, E. B., Flinsenberg, T. W. H., van der Grein, S. G. & Boes, M. Antigen processing and remodeling of the endosomal pathway: requirements for antigen cross-presentation. Frontiers in immunology 3, 37, 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00037 (2012).

Brömme, D. et al. Functional expression of human cathepsin S in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Purification and characterization of the recombinant enzyme. Journal of Biological Chemistry 268, 4832–4838 (1993).

Lennon-Dumenil, A. M. et al. Analysis of Protease Activity in Live Antigen-presenting Cells Shows Regulation of the Phagosomal Proteolytic Contents During Dendritic Cell Activation. Journal of Experimental Medicine 196, 529–540, 10.1084/jem.20020327 (2002).

McCormick, P. J., Martina, J. A. & Bonifacino, J. S. Involvement of clathrin and AP-2 in the trafficking of MHC class II molecules to antigen-processing compartments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102, 7910–7915, 10.1073/pnas.0502206102 (2005).

van Niel, G., Wubbolts, R. & Stoorvogel, W. Endosomal sorting of MHC class II determines antigen presentation by dendritic cells. Current opinion in cell biology 20, 437–444, 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.05.011 (2008).

Boes, M. et al. T Cells Induce Extended Class II MHC Compartments in Dendritic Cells in a Toll-Like Receptor-Dependent Manner. The Journal of Immunology 171, 4081–4088, 10.4049/jimmunol.171.8.4081 (2003).

Harding, C. V. & Geuze, H. J. Immunogenic peptides bind to class II MHC molecules in an early lysosomal compartment. The Journal of Immunology 151, 3988–3998 (1993).

Abbas, A. K., Lichtman, A. H. & Pillai, S. Cellular and molecular immunology. 7th edn, (Elsevier/Saunders, 2012).

Moore, S., ‘Round-the-horn site-directed mutagenesis, <http://openwetware.org/wiki/%27Round-the-horn_site-directed_mutagenesis> (2005) Date of access: 24/05/2015.

Dall, E. & Brandstetter, H. Activation of legumain involves proteolytic and conformational events, resulting in a context- and substrate-dependent activity profile. Acta Crystallographica Section F Structural Biology and Crystallization Communications 68, 24–31, 10.1107/S1744309111048020 (2012).

Hoffmann-Sommergruber, K. et al. High-level expression and purification of the major birch pollen allergen, Bet v 1. Protein Expr Purif 9, 33–39, 10.1006/prep.1996.0671 (1997).

Marković-Housley, Z. et al. Crystal Structure of a Hypoallergenic Isoform of the Major Birch Pollen Allergen Bet v 1 and its Likely Biological Function as a Plant Steroid Carrier. Journal of Molecular Biology 325, 123–133, 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)01197-X (2003).

Weichenberger, C. X., Byzia, P. & Sippl, M. J. Visualization of unfavorable interactions in protein folds. Bioinformatics 24, 1206–1207, 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn108 (2008).

Thompson, J. D., Higgins, D. G. & Gibson, T. J. Clustal-W - Improving the Sensitivity of Progressive Multiple Sequence Alignment through Sequence Weighting, Position-Specific Gap Penalties and Weight Matrix Choice. Nucleic acids research 22, 4673–4680, 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673 (1994).

Bond, C. S. & Schuttelkopf, A. W. ALINE: a WYSIWYG protein-sequence alignment editor for publication-quality alignments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 65, 510–512, 10.1107/S0907444909007835 (2009).

Stoorvogel, W., Strous, G. J., Geuze, H. J., Oorschot, V. & Schwartzt, A. L. Late endosomes derive from early endosomes by maturation. Cell 65, 417–427, 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90459-C (1991).

Muller, S., Dennemarker, J. & Reinheckel, T. Specific functions of lysosomal proteases in endocytic and autophagic pathways. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1824, 34–43, 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.07.003 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank Martina Wiesbauer, Arthur Hinterholzer, Esther Schönauer, Line Hyltoft Kristensen and Stefan Kofler for technical help. We appreciate the support by the Austrian Science Funds (FWF) for funding (project W_01213).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.D. produced cystatin C and human legumain, R.F. performed all other experiments, all authors analyzed data. R.F. and H.B. prepared the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Freier, R., Dall, E. & Brandstetter, H. Protease recognition sites in Bet v 1a are cryptic, explaining its slow processing relevant to its allergenicity. Sci Rep 5, 12707 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep12707

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep12707

This article is cited by

-

Formaldehyde treatment of proteins enhances proteolytic degradation by the endo-lysosomal protease cathepsin S

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Ligand Binding of PR-10 Proteins with a Particular Focus on the Bet v 1 Allergen Family

Current Allergy and Asthma Reports (2020)

-

Hydrophobic ligands influence the structure, stability, and processing of the major cockroach allergen Bla g 1

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

α-Gal on the protein surface affects uptake and degradation in immature monocyte derived dendritic cells

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Retinoic acid prevents immunogenicity of milk lipocalin Bos d 5 through binding to its immunodominant T-cell epitope

Scientific Reports (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.