Abstract

Little information is available regarding the adverse effects of pesticides on natural honey bee populations. This study highlights the detrimental effects of pesticides on honey bee olfaction through behavioural studies, scanning electron microscopic imaging of antennal sensillae and confocal microscopic studies of honey bee brains for calcium ions on Apis cerana, a native Indian honey bee species. There was a significant decrease in proboscis extension response and biologically active free calcium ions and adverse changes in antennal sensillae in pesticide exposed field honey bee populations compared to morphometrically similar honey bees sampled from low/no pesticide sites. Controlled laboratory experiments corroborated these findings. This study reports for the first time the changes in antennal sensillae, expression of Calpain 1(an important calcium binding protein) and resting state free calcium in brains of honey bees exposed to pesticide stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pesticide exposure can have direct effects on individual bees as well as indirect effects on entire colonies1 and has been cited as one of the potential causes for global honey bee loss through colony collapse disorder2,3. Loss of pollinators especially honey bees, may have adverse bearing on agricultural economy and may also affect wild crop diversity, crop production, food security and overall ecosystem stability4,5. Apart from population loss6,7, other adverse effects include induced oxidative stress8 and behavioral deformities e.g. learning and communication, homing, foraging success and neurophysiology6,9,10. However, critical information gap exists on the response of natural populations of native honey bee to multiple pesticide exposures in field conditions8,11.

Olfaction plays a crucial and determining role in nectar and pollen search, mating, alarm, defense, orientation, self-colony recognition and incorporation of all conducts within the honey bee hive12,13,14. Measurement of proboscis extension response/reflex (PER) has been used to identify the extent of memory acquisition and retention in honey bees and has also been greatly used to assess the effects of pesticides on honey bees10,15. Odor detection is facilitated by olfactory receptor neurons (ORNs) located below various sensillae16. Sensillae types and distribution in honey bee species are well described through Scanning Electron Microscopic (SEM) studies17,18,19. In order to comprehend the neuronal processes fundamental to olfactory learning, biophysical properties such as ion channel activity and calcium ion (Ca2+) in particular have also been reported within the neurons of the olfactory pathway in the honey bee brain20,21,22. Long term memory (LTM) formation and its role in effective olfaction is an important survival strategy of the honey bees. It has been reported that most of the molecules shown to be involved in LTM formation depend directly or indirectly on Ca2+ 22 and several studies consequently suggest that Ca2+ may be the preliminary trigger for LTM development22. Many studies have established a link between Ca2+ concentrations and memory formation and processing21,22,23,24 with the argument that Ca2+ crucially helps in the establishment of “long-term potentiation” (cellular phenomenon underlying LTM)22,25,26. Calcium imaging studies have helped to establish how olfactory information is initially coded in the antennal lobe27,28, the primary olfaction centre16 and lateral horn and the mushroom bodies called the higher-order olfactory centers16. Reports have shown that Calpain, an important calcium handling protein, also plays a significant role in memory formation in the honey bee brains29,30,31.

In the present paper we attempt to assess the impact of pesticides on olfaction of natural populations of Apis cerana, a native Indian honey bee, sampled across pesticide intensive agricultural landscapes in an Eastern Indian state of Odisha8. We compared the field samples of A. cerana from a high pesticide intensive cropping site with a low or no pesticide intensity site for PER, morphometry, sensilla number and distribution and availability of resting state free calcium (Ca2+). We also corroborated the findings with controlled laboratory experiments. As per the previous study8, the chosen field sites in Odisha are Panchalingeshwar (Lat. 21.43 oN; Long. 86.75 oE), the low intensity cropping site (LIC) and Jaleshwar (Lat. 21.82 oN; Long. 87.22 oE), the high intensity cropping site (HIC).

Results

Intensification sites

The field sites were chosen based on the study by Chakrabarti et al. 20148. The high intensity cropping site (HIC) – the high pesticide use site – recorded higher pesticide residues in the soil samples as well as higher pesticide use by the farmers compared to the low intensity cropping site (LIC) – the site of low pesticide use (Supplementary Figure 1).

Morphometry measurements

All the honey bee samples were found to be morphometrically similar.

No significant difference was observed between the honey bees sampled from LIC and HIC with respect to wet weight (p = 0.498, df = 298, t = 0.678), antennal length (p = 0.522, df = 298, t = 0.641) and total body length (p = 0.92, df = 298, t = 0.097). Mean total body length (8 X magnification), mean wet weight and mean antennal length (25 X magnification) of honey bees sampled from LIC were observed to be 11.32 mm ± 0.03, 0.085 gm ± 0.001 and 3.297 mm ± 0.01 respectively. Mean total body length (8 X magnification), mean wet weight and mean antennal length (25 X magnification) of honey bees sampled from HIC were observed to be 11.32 mm ± 0.04, 0.0846 gm ± 0.001 and 3.287 mm ± 0.011 respectively (Fig. 1a).

(a) Figure showing no significant difference in the honey bees with respect to the three morphometrical characters – antennal length, total length of body and wet weights – in all the groups of honey bees. Mean wet weight is plotted on the secondary axis. LIC is low intensity cropping site, HIC is high intensity cropping site, Lab control is the control group of honey bees in laboratory and Lab pesticide are the pesticide treated honey bees in the laboratory. (b) Figure showing significant decrease in proboscis extension response (PER) of honey bees treated with pesticides in laboratory and exposed to pesticides in field. There was no significant difference observed in PER of the honey bee groups prior to treatment in the laboratory.

Similarly, no significant difference was also observed between the control and treatment groups of honey bee samples in the laboratory with respect to wet weight (p = 0.198, df = 298, t = −1.29), antennal length (p = 0.93, df = 298, t = 0.08) and total length of body (p = 0.09, df = 298, t = −1.68). The mean values of wet weight, antennal length (25 X magnification) and total body length (8 X magnification) in control groups were observed to be 0.0872 gm ± 0.0005, 3.3043 mm ± 0.009 and 11.438 mm ± 0.023 respectively and in treatment groups were found to be 0.086 gm ± 0.0009, 3.305 mm ± 0.008 and 11.365 mm ± 0.0371 respectively in the laboratory (Fig. 1a).

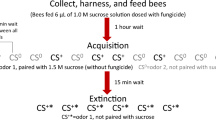

Proboscis extension reflex (PER)

Proboscis extension reflex or response (PER) was checked in honey bees prior to testing in the laboratory. No significant difference was observed in PER across the six time cohorts between the two groups of honey bees – one group was then considered as control and the other was treated with pesticides (Table 1a). The positively responding honey bees were chosen for treatment experiments in the laboratory. The field samples were directly tested for PER. A significant decrease in PER in the honey bees sampled from HIC compared to LIC across all six time cohorts (1 minute, 3 minutes, 5 minutes, 10 minutes, 30 minutes and 60 minutes) (Table 1b) was observed. Similarly, a significant decrease was also observed in the treatment groups of honey bees in laboratory compared to their respective control groups across six time cohorts (Table 1b). This indicates that PER, being a direct behavioural response of olfactory learning and memory retention in honey bees, was affected in those honey bees which were exposed to/treated with pesticides in field and laboratory respectively (Fig. 1b).

Scanning electron microscopic studies (SEM) of the honey bee antenna

Having observed a direct behavioural response to pesticide, the anatomical changes in the honey bee antennae were then verified. The antennal sensillae of the honey bees, responsible for olfaction, were checked for abnormalities. A total of 14 sensillae types were identified across 10 antennal segments of the randomly collected foragers by SEM. Repeated measure ANOVA revealed a significantly higher number of different sensillae types, except one, in LIC (Supplementary Table 1). A significantly higher number in HIC was observed only with respect to sensory placodea shallow (Supplementary Table 1). However, no significant difference was observed in the populations exposed to pesticides in the laboratory after twenty four hours of pesticide exposure compared to the control groups (Supplementary Table 1). Tukey – Post Hoc test values with significance have been provided in Supplementary Table 2. The average number of sensillae in field and laboratory populations of honey bees for all the sensillae types is furnished in Fig. 2.

Figure showing mean number of antennal sensillae in all the honey bee experimental groups.

1: Sensory placodea, deep, 2: Sensory placodea, shallow, 3: Sensory ampullacea, 4: Sensory coeloconica, 5: Sensory basiconica, 6: Sensory campaniforme, 7: Sensory trichodea A, 8: Sensory trichodea B1, 9: Sensory trichodea B2, 10: Sensory trichodea C, 11: Sensory trichodea D, 12: Setae A1 & A2, 13: Seta A3, 14: Seta B. * = p < 0.05.

A marked deformation was observed in the sensillae of the pesticide affected populations and in extreme cases, crack like marks were found on the sensory placodea deep, sensory placodea shallow (Fig. 3a,b) and sensory campaniforme (Supplementary Figure 2b) across various segments of the antennae. Sensory coeloconica seemed considerably deformed as well (Fig. 3c). A significant reduction in the diameter (p = 0.002, df = 58, t = 3.33) was observed in sensory campaniforme in HIC (16.18 μm ± 0.1) compared to LIC (16.72 μm ± 0.13). A significantly larger diameter (p = 0.0001, df = 58, t = 9.47) was observed in sensory placodea deep in LIC samples along the long axis (18.07 μm ± 0.12) compared to HIC samples (16.08 μm ± 0.18). The sensory trichodea B2 seemed considerably longer having more curvature in the control (LIC) populations of honey bees compared to HIC populations (Fig. 3d).

Figure showing representative scanning electron microscopic images of various antennal sensillae of honey bees across LIC (control) and HIC (pesticide) field sites.

(a) Sensory placodea deep; (b) Sensory placodea shallow; (c) Sensory coeloconica; (d) Sensory trichodea B2. LIC is low intensity cropping site and HIC is high intensity cropping site.

Resting state free calcium availability in honey bee brains

The live honey bee brains were exposed by removing the cuticle and were stained with fura – 2 – dextran and tetramethylrhodamine dextran at the same time as the honey bee was stimulated with odour (linalool). The live brain cells had taken up the stain and the fluorescence observed was directly proportional to the resting state free Ca+2 of the stimulated live brain.

A marked higher intensity of green fluorescence indicating free Ca2+ was observed in the brain (encompassing parts of mushroom body and the antennal lobe region of representative honey bee brains, stained with tetramethylrhodamine dextran and fura – 2 - dextran) of honey bees sampled from the LIC field sites compared to the HIC samples (Fig. 4). Similarly in the laboratory experiments, a lower fluorescence was observed in the mushroom body and antennal lobe regions of the brains of pesticide treated honey bees compared to the untreated control populations (Fig. 5a) indicating less free Ca2+ in the former group of honey bees.

Figure showing olfactory regions of representative stained honey bee brain sampled from LIC (control) and HIC (pesticide) field sites.

Magnification 20 X. Scale = 300 μm. Tetramethylrhodamine dextran stains whole brain red, Fura – 2 - dextran imparts green fluorescence and merged images show both stains together. (a) Part of mushroom body in LIC populations of honey bees; (b) Part of mushroom body in HIC populations of honey bees; (c) Antennal lobe region in LIC populations of honey bees; (d) Antennal lobe region in HIC populations of honey bees. LIC is low intensity cropping site and HIC is high intensity cropping site; (e) Line diagram of honey bee whole brain showing locations of mushroom body and antennal lobes.

(a) Figure showing olfactory regions of representative stained honey bee brain sampled from control and pesticide groups in laboratory. Magnification 20 X. Scale = 300 μm. Tetramethylrhodamine dextran stains whole brain red, Fura – 2 - dextran imparts green fluorescence and merged images show both stains together. (i) Part of mushroom body in control groups of honey bees; (ii) Part of mushroom body in pesticide treatment groups of honey bees; (iii) Antennal lobe region in control groups of honey bees; (iv) Antennal lobe region in brains of pesticide treatment groups of honey bees. (b) Figure showing bound to free calcium ratios of honey bee populations across two field sites HIC and LIC and across laboratory groups of control and pesticide treated honey bees. LIC is low intensity cropping site and HIC is high intensity cropping site. * = p < 0.01.

Fluorimetry studies of the stained honey bee brains also revealed a significantly higher bound-to-free calcium ratio (z = −3.00227, p = 0.002680) for the HIC honey bees (1.81 ± 0.4) compared to the LIC samples (1.30 ± 0.1) (Fig. 5b). Similarly, a significantly higher bound-to-free calcium ratio (z = −3.26718, p = 0.001086) was observed in honey bees treated with pesticides in laboratory (2.02 ± 0.16) compared to untreated control group (1.26 ± 0.05) (Fig. 5b). A higher bound to free calcium ratio indicates less free Ca2+ in the brains of pesticide exposed/treated groups of honey bees and this corroborates with the fluorescence data from the confocal microscopic studies.

This was further corroborated by plotting the average intensities of both stains where a distinct down regulation was observed in fura – 2 – dextran absorbance in the field pesticide exposed honey bees (HIC) compared to LIC whereas tetramethylrhodamine dextran showed a similar trend between HIC and LIC (Fig. 6a,b). Figure 6a,b indicate the average intensities of both stains across the mushroom body and antennal lobe regions respectively in two representative field samples of honey bees (LIC and HIC) at every frame i.e. 4 μm optical sections up to 256 frames. Similarly, among laboratory samples, tetramethylrhodamine dextran also showed a similar trend between control and pesticide treatment groups whereas, a distinct down regulation was observed in the fura – 2 - dextran absorbance in pesticide treated samples compared to the control groups (Fig. 6c,d).

Figure showing the average intensities of two stains (fura – 2 – dextran and tetramethylrhodamine dextran) across the mushroom body and antennal lobe regions at every frame i.e. 4 μm optical sections up to 256 frames in two representative field samples of honey bees in (a) Mushroom body region and (b) Antennal lobe region. LIC: low intensity cropping or control site; HIC: high intensity cropping or pesticide site. Two representative laboratory samples of honey bees across the mushroom body and antennal lobe regions at every frame i.e. 4 μm optical sections up to 256 frames are shown in (c) Mushroom body region and (d) Antennal lobe region.

Calpain 1 expression in honey bee brains

Western blot analyses revealed a significant difference in the expression of Calpain 1 in the brains of honey bees sampled across both LIC and HIC (1 tail Mann Whitney U test; n = 5) as well as in the laboratory. A significant increase of 1.87 ± 0.04 fold (1 tail Mann Whitney U test; n = 5; p < 0.01) was observed in Calpain 1 expression in LIC honey bee brain samples compared to HIC samples (Fig. 7). A similar response pattern was observed in the laboratory samples where, a significant increase in Calpain 1 expression (2.14 ± 0.07 fold), was observed in the brains of control honey bees compared to the pesticide treated individuals (1 tail Mann Whitney U test; n = 5; p < 0.01) (Fig. 7).

(a) Representative blots showing Calpain 1expression levels among honey bee brains from both field and laboratory populations; (b) respective SDS-PAGE gels stained with Coomassie blue confirming equal loading; (c) Graph indicates the change in expression of Calpain 1 normalized by Coomassie blue stained gel. C: Laboratory control and P: Laboratory pesticide treatment groups. LIC: Low intensity cropping site and HIC: High intensity cropping site. The marker lane shows the relative positioning of the bands. *p < 0.01 for field populations; #p < 0.01 for laboratory populations.

Discussion

Multiple pesticide exposure for pollinators is a common phenomenon in intensive agricultural landscapes8,32. The increasing use of pesticides in developing countries33 has hence alarmingly raised the impacts of such pesticides on non target organisms. Although a number of laboratory studies have measured the impacts, it has been argued that laboratory studies of shorter durations are only a partial evaluation of the field realistic impacts10. Therefore, for a comprehensive assessment of the impact, field, semi – field and laboratory – all trials would be important in assessing such impacts8,11. In this context, our study holds added importance as we have not only verified that multiple pesticides induce impacts on the olfaction capacities of honeybees through laboratory trials, but also explored such impacts on wild populations of native honey bees.

The proboscis extension reflex (PER) is frequently used in a classical conditioning (Pavlovian) milieu for evaluating learning and memory in a variety of insect species including honey bees34. The ecological consequences of PER have been already reported34,35,36. It has also been reported through PER estimation that odour discrimination is frequently comparable between honeybees trained under controlled (honey bees in laboratory cages) and free-flying conditions (as in field populations of wild bees)34,37,38,39 and olfactory memories remain unchanged to variations in circumstances34,40,41,42,43, e.g., reallocation from natural to simulated environments34,36,40. Hence it can be assumed that in our study the significant changes in the observed PER between field samples is for differential pesticide exposure which is further corroborated by the laboratory experiments.

Since no significant difference was observed between the samples with respect to wet weight, antennal length and over all body length, we argue that difference in antennal sensillae in the randomly sampled foragers across two pesticide use sites was not because of any morphometric changes in the antennal characteristics across the gradient but because of pesticide exposure. The treatment and control samples from laboratory showed no significant difference in antennal sensillae after twenty four hours of exposure. We argue that the changes in sensillae in the honey bees exposed to pesticides happen over longer pesticide exposure in natural condition and can be attributed to developmental impairments leading to deformed/reduced number of sensillae. Pesticide exposure happens as contaminated food is brought back to the hive by the foragers and the subsequent honey bee generations are reared on it. Honey bees can be easily exposed to pesticides over long durations of time by transfer of such pesticide residues to the hives44. Our observed significant difference in the field populations’ sensillae and not in the shorter duration laboratory trials is due to the former’s much longer exposure to pesticides spanning several generations.

Even though a significant difference was observed in the sensillae numbers between LIC and HIC samples of field populations of honey bees, the average number of only sensory placodea shallow was higher in HIC populations compared to LIC populations unlike rest of the other sensillae. We assume that there may have been a gradual transformation of sensory placodea deep to sensory placodea shallow in the pesticide exposed populations. The observed affected sensillae in our study have been reported earlier to play an important role in olfaction45,46,47. Hence, their deformation, damage, size and number reduction in the antennae of pesticide exposed wild honey bees can be assumed to interfere with olfaction. To our knowledge, this is the first report of any change in the antennal sensillae in the pesticide exposed natural honey bee populations.

It was observed that the control populations in laboratory and the LIC field samples showed higher fluorescence in the honey bee brain, particularly around the antennal lobe and the mushroom body regions and lower bound to free calcium ratio compared to their respective pesticide treatment groups and HIC samples. This is indicative of less free Ca+2 in pesticide exposed/treated honey bee brains and may affect the processes underlying olfaction which are dependent on availability of free Ca+2. The laboratory results have helped to validate our field results. A lower bound to free Ca2+ ratio indicates higher free Ca+2 and hence a higher fluorescence as evident from our results. It has been reported that only free Ca2+ is biologically active48. It is also known that Ca2+ indicators bind and interact only with freely diffusible Ca2+ ions49 and that free Ca2+ - fura-2 emits greater than bound Ca2+ - fura-2 when excitation wavelength is longer than 370 nm50. It was also observed that between HIC samples and pesticide treated laboratory samples, the HIC samples showed a higher fluorescence. We assume that this could be because in laboratory, the honey bees are only allowed to feed from the pesticide mixture. However in field, they still have an additional option – even though very limited in HIC as evident from our previous report of field surveys8 – to feed from less pesticide sprayed or pesticide free natural vegetation.

Calpain is an important calcium handling protein30. It cleaves protein kinase C (PKC) to its activated form protein kinase M (PKM) which in turn is responsible for memory formation30. Calpain has also been previously reported in the honey bees29 and is known to play an important role in memory formation30,31. Our study indicates a higher expression of Calpain 1 in brains of control populations of honey bees, from both field and laboratory. This may trigger a more efficient handling of free calcium which in turn might benefit the olfactory learning and memory in the honey bee population that are not exposed to pesticides. Changes in Calpain 1 expression level corroborated our findings of confocal microscopy and fluorimetric analyses for resting state free calcium during pesticide stress.

To our knowledge, this is also the first report of change in resting state free Ca2+ across honey bee populations due to pesticide exposure, as studied by confocal microscopy and fluorimetric analysis. These findings also show a decrease in resting state free Ca+2 and Calpain 1 expression in honey bee brains exposed to pesticides and to our knowledge, this is the first report of such phenomenon in natural honey bee populations in the intensive agricultural sites with high pesticide load.

Pollen odour cues help bees to locate food resources51. Enhanced olfactory learning performance helps to improve foraging success in bees, as evident from reports in bumble bees52 and honey bees53. Also, daily tasks of honey bees are set by pheromonal instructions14 in which olfaction, once more, is a crucial factor. Therefore, impaired olfaction would have strong influence on the population health. Pesticide treatment may lead to impairment in olfaction, memory or both. However the effects of pesticides on memory impairment alone will require further investigation. However, further investigation is necessary to check the dynamics of calcium flux in the honey bee brains exposed to pesticide load.

Our studies hence not only show the adverse effects of pesticide exposure on an important behaviour such as PER of the honey bees but also delve into the underlying micro structural and neuro-physiological processes contributing to such changes. Damaged olfaction thus might have critical consequences for the very survival of honey bees and such assessment requires to be undertaken for other non – target insect groups too especially for other beneficial pollinator groups.

Materials and Methods

Detailed methods have been incorporated in supplementary information (supplementary methods).

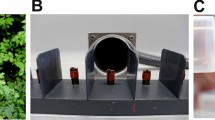

Agricultural intensification landscapes

The agricultural landscape was chosen in the Eastern Indian state of Odisha based on the work by Chakrabarti et al. (2014)8. Two locations chosen were marked as high intensity cropping (HIC) and low intensity cropping (LIC).

Sampling honey bees

The individual foragers of Apis cerana were randomly sampled at the nest entrance. A total of three colonies in each site were chosen for all experiments.

Exposure of honey bees to pesticides in laboratory and pesticide treatments

The honey bees were acclimatized and reared in laboratory cages based on the methods by Chakrabarti et al. 20148. Three pesticides in combination were used as was reported in a previous study8 - an organophosphorus (OP) pesticide, a synthetic pyrethroid (SP) - and an endosulfan pesticide (ES) – in combination as 12.5% OP + 4% SP + 15% ES (as comparable to the doses used by farmers in field).

Morphometric measurements

Randomly sampled forager honey bees from field sites were used for morphometric measurements of total body length, antennal length and wet body weights.

Proboscis extension reflex (PER) studies

The protocol is based on the methods described by Bitterman et al. (1983)54, Sandoz et al. (2000)41, Decourtye et al. (2004)55, Decourtye et al. (2005)9, Frost et al. (2012)34 and Kirkerud et al. (2013)56. The source of odour was a small piece of filter paper (40 × 30 mm2) soaked in 10 μl of linalool (95–97% purity, Sigma, U.S.A.). Positive PER were recorded as “Yes” or “1” and negative responses were recorded as “No” or “0” during the test trials where only odour was delivered to the honey bees across 6 time cohorts.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

A total of 14 sensilla types were identified across 10 antennal segments of the randomly collected foragers17,18 by SEM.

Calcium imaging using confocal microscopy

Live honey bees were mounted on a glass holder after anesthetizing them over ice. Low melting point hard wax was used to fix the eyes and thorax to the glass holder. The cuticle was gently removed from the head region and the stain concoction (fura – 2 – dextan and tetramethylrhodamine dextran) was injected in to the soma region of the mushroom body. The staining method was based on the modified protocol of Haehnel et al. (2009)57. The brains were removed and prepared for confocal microscopy57. Whole brains were mounted for confocal imaging58,59,60.

Bound to free calcium ratio using fluorimetry

The absorbance or optical density (OD) values of bound to free calcium was calculated for the pesticide and control groups of honey bees from both field and laboratory treatment experiments by the formula49 ΔCa2+ = FCaB ÷ FCaF. Here ΔCa2+ is the ratio of bound to free calcium; FCa B and FCa F are the absorbance values of bound and free calcium respectively.

Western blot and quantification of Calpain 1

Protein preparation, western blotting and band quantification were done based on previous studies8. Calpain 1 bands were obtained from thirty microgram of total protein extract from honey bee brains through western blotting technique. Equal loading of protein samples was confirmed by Coomassie blue staining of the gel. The blots were scanned; bands were normalized by Coomassie and quantitated using GelDoc XR system and Quantity One® software version 4.6.3 (Bio-Rad, California, USA).

Data Analyses

Data was analyzed using Statistica software (version 10).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Chakrabarti, P. et al. Field populations of native Indian honey bees from pesticide intensive agricultural landscape show signs of impaired olfaction. Sci. Rep. 5, 12504; doi: 10.1038/srep12504 (2015).

References

Heylen, K., Gobin, B., Arckens, L., Huybrechts, R. & Billen, J. The effects of four crop protection products on the morphology and ultrastructure of the hypopharyngeal gland of the European honeybee. Apis mellifera. Apidologie. 10.1051/apido/2010043 (2010).

Frazier, M., Mullin, C., Frazier, J. & Ashcraft, S. What have pesticides got to do with it? Am. Bee J. 148, 521–524 (2008).

Pettis, J. S., vanEngelsdorp, D., Johnson, J. & Galen, D. Pesticide exposure in honey bees results in increased levels of the gut pathogen Nosema. Naturwissenschaften 99, 153–158 (2012).

Gallai, N., Salles, J.-M., Settel, J. & Vaissière, B. E. Economic valuation of the vulnerability of world agriculture confronted with pollinator decline. Ecol. Econ. 68, 810–821 (2009).

Potts, S. G. et al. Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25, 345–53 (2010).

Henry, N. et al. A common pesticide decreases foraging success and survival in honey bees. Science 336, 348–350 (2012).

Whitehorn, P. R., O’Connor, S., Wackers, F. L. & Goulson, D. Neonicotinoid pesticide reduces bumble bee colony growth and queen production. Science 336, 351–352 (2012).

Chakrabarti, P., Rana, S., Smith, B., Sarkar, S. & Basu, P. Pesticide induced oxidative stress in laboratory and field populations of native honey bees along intensive agricultural landscapes in two Eastern Indian states. Apidologie 10.1007/s13592-014-0308-z (2014).

Decourtye, A., Armengaud, C., Renou, M., Devillers, J. & Cluzeau, S. Comparative sublethal toxicity of nine pesticides on olfactory learning performances of the honeybee Apis mellifera. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 48, 242–250 (2005).

Desneux, N., Decourtye, A. & Delpuech, J. M. The sublethal effects of pesticides on beneficial arthropods. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 52, 81–106 (2007).

Osborne, J. L. Bumble bees and pesticides. Nature 491, 43–45 (2012).

Blum, M. S. in The hive and the honey bee Revised edn. (ed. Graham, J. M. ) Honey bee pheromones, 373–400 (Dadant and sons, 1992).

Vadas, R. L. Jr. The Anatomy of an Ecological Controversy: Honey-Bee Searching Behavior. Oikos 69, 158–166 (1994).

Katzav-Gozansky, T., Soroker, V. & Hefetz, A. Honeybees Dufour’s gland – idiosyncrasy of a new queen signal. Apidologie 33, 525–537 (2002).

Han, P., Niu, C.-Y., Lei, C.-L., Cui, J.-J. & Desneux, N. Use of an innovative T-tube maze assay and the proboscis extension response assay to assess sublethal effects of GM products and pesticides on learning capacity of the honey bee Apis mellifera L. Ecotoxicology 19, 1612–1619 (2010).

Sandoz, J.-C. in Honeybee Neurobiology and Behavior (eds Giovanni, C. G. et al.) Ch. 4, 234–321 (Springer, 2012).

Naik, D. G. et al. Antennal sensilla of adult worker Apis cerana. J. Apicult. Res. 34, 205–208 (1995).

Suwannapong, G., Seanbualuang, P. & Benbow, M. E. Using sensillum potential analysis to quantify pheromone sensing of the antennal sensilla of Apis florae Fabricius (1787), foragers and guards. Journal of Asia-Pacific Entomology 14, 7–10 (2011).

Jung, J. W., Park, K. W., Oh, H.-W. & Kwon, H. W. Structural and functional differences in the antennal olfactory system of worker honey bees of Apis mellifera and Apis cerana, Journal of Asia-Pacific Entomology 10.1016/j.aspen.2014.01.012 (2014).

Grünewald, B. Differential expression of voltage-sensitive K+ and Ca2+ currents in neurons of the honeybee olfactory pathway. J. Exp. Biol. 206, 117–129 (2003).

Woodside, B. L., Borroni, A. M., Hammonds, M. D. & Teyler, T. J. NMDA receptors and voltage-dependent calcium channels mediate different aspects of acquisition and retention of a spatial memory task. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 81, 105–114 (2004).

Perisse, E. Early calcium increase triggers the formation of olfactory long-term memory in honeybees. BMC Biology 10.1186/1741 7007-7-30 (2009).

Quevedo, J. et al. L-type voltage-dependent calcium channel blocker nifedipine enhances memory retention when infused into the hippocampus. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 69, 320–325 (1998).

Bauer, E. P., Schafe, G. E. & LeDoux, J. E. NMDA receptors and L-type voltage-gated calcium channels contribute to long-term potentiation and different components of fear memory formation in the lateral amygdala. J. Neurosci. 22, 5239–5249 (2002).

Lisman, J. E. Three Ca2+ levels affect plasticity differently: the LTP zone, the LTD zone and no man’s land. J. Physiol. 532, 285 (2001).

Reymann, K. G. & Frey, J. U. The late maintenance of hippocampal LTP: requirements, phases, “synaptic tagging”, “late-associativity” and implications. Neuropharmacology 52, 24–40 (2007).

Galizia, C. G., Küttner, A., Joerges, J. & Menzel, R. Odour representation in honeybee olfactory glomeruli shows slow temporal dynamics: an optical recording study using a voltage sensitive dye. J. Insect Physiol. 46, 877–886 (2000).

Sachse, S. & Galizia, C. G. Role of inhibition for temporal and spatial odor representation in olfactory output neurons: A calcium imaging study. J. Neurophysiol. 87, 1106–1117 (2002).

Grünbaum, L. & Müller, U. Induction of a Specific Olfactory Memory Leads to a Long-Lasting Activation of Protein Kinase C in the Antennal Lobe of the Honeybee. J. Neurosci. 18, 4384–4392 (1998).

Müller, U. in Invertebrate Learning and Memory: Memory phases and signaling cascades in honey bees (eds Menzel, R. & Benjamin, P. R. ) 435–449 (Academic Press, 2013).

Baudry, M., Chou, M. M. & Bi, X. Targeting calpain in synaptic plasticity. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 17, 579–592 (2013).

Krupke, C. H., Hunt, G. J., Eitzer, B. D., Andino, G. & Given, K. Multiple routes of pesticide exposure for honey bees living near agricultural fields. PLoS One 7, e29268 (2012).

Schreinemachers, P. & Tipraqsa, P. Agricultural pesticides and land use intensification in high, middle and low income countries. Food Policy 37, 616–626 (2012).

Frost, E. H., Shutler, D. & Hillier, N. K. The proboscis extension reflex to evaluate learning and memory in honeybees (Apis mellifera): some caveats. Naturwissenschaften 10.1007/s00114-012-0955-8 (2012).

Sandoz, J. C., Roger, B. & Pham-Delègue, M. H. Olfactory learning and memory in the honeybee: comparison of different classical conditioning procedures of the proboscis extension response. C. R. Acad. Sci. 318, 749–755 (1995).

Farina, W. M., Grüter, C. & Díaz, P. C. Social learning of floral odours inside the honeybee hive. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 272, 1923–1928 (2005).

Mauelshagen, J. & Greggers, U. Experimental access to associative learning in honeybees. Apidologie 24, 249–266 (1993).

Pham-Delègue et al. Behavioural discrimination of oilseed rape volatiles by the honeybee Apis mellifera L. Chem. Senses 18, 483–494 (1993).

Laloi et al. Recognition of complex odors by restrained and freeflying honeybees (Apis mellifera). J. Chem. Ecol. 26, 2307–2319 (2000).

Gerber et al. Honey bees transfer olfactory memories established during flower visits to a proboscis extension paradigm in the laboratory. Anim. Behav. 52, 1079–1085 (1996).

Sandoz, J. C., Laloi, D., Odoux, J. F. & Pham-Delègue, M. H. Olfactory information transfer in the honeybee: compared efficiency of classical conditioning and early exposure. Anim. Behav. 59, 1025–1034 (2000).

Chaffiol, A., Laloi, D. & Pham-Delègue, M. H. Prior classical olfactory conditioning improves odour-cued flight orientation of honey bees in a wind tunnel. J. Exp. Biol. 208, 3731–3737 (2005).

Carcaud, J., Roussel, E., Giurfa, M. & Sandoz, J. C. Odour aversion after olfactory conditioning of the sting extension reflex in honeybees. J. Exp. Biol. 212, 620–626 (2009).

Villa, S., Vighi, M., Finizio, A. & Serini, G. B. Risk assessment for honeybees from pesticide exposed pollen. Ecotoxicology 9, 287–297 (2000).

Gupta, M. Scanning electron microscopic studies of antennal sensilla of adult worker Apis florea F (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Apidologie 23, 47–56 (1992).

Pophof, B. Olfactory responses recorded from sensilla coeloconica of the silkmoth Bombyx mori. Physiol. Entomol. 22, 239–248 (1997).

Suwannapong, G., Eiri, D. M. & Benbow, M. E. Honeybee Communication and Pollination. New Perspectives in Plant Protection ISBN: 978-953-51-0490-2 (2012).

Grienberger, C. & Konnerth, A. Imaging Calcium in Neurons. Neuron 73, 862–885 (2012).

Paredes, R. M., Etzler, J. C., Watts, L. T. & Lechleiter, J. D. Chemical Calcium Indicators. Methods 46, 143–151 (2008).

Takahashi, A., Camacho, P., Lechleiter, J. D. & Herman, B. Measurement of Intracellular Calcium. Physiol. Rev. 79, 1089–1125 (1999).

Cook et al. Could learning of pollen odours by honey bees (Apis mellifera) play a role in their foraging behaviour? Physiol.Entomol. 30, 164–174 (2005).

Raine, N. E. & Chittka, L. The correlation of learning speed and natural foraging success in bumblebees, Proc. R. Soc. London B 275, 803–808 (2008).

Dukas, R. & Visscher, P. K. Lifetime learning by foraging honey bees. Anim. Behav. 48, 1007–1012 (1994).

Bitterman, M. E., Menzel, R., Fietz, A. & Schäfer, S. Classical conditioning of proboscis extension in honeybees (Apis mellifera). J Comp. Psychol. 97, 107–119 (1983).

Decourtye et al. Imidacloprid impairs memory and brain metabolism in the honeybee (Apis mellifera L.). Pestic. Biochem. Phys. 78, 83–92 (2004).

Kirkerud, N. H., Wehmann, H. N., Galizia, C. G. & Gustav, D. APIS-a novel approach for conditioning honey bees. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 7, 29 (2013).

Haehnel, M., Froese, A. & Menzel, R. In vivo Ca2+- Imaging of Mushroom Body Neurons During Olfactory Learning in the Honey Bee. JoVE 10.3791/1353 (2009).

Yamagata, N., Schmuker, M., Szyszka, P., Mizunami, M. & Menzel, R. Differential odor processing in two olfactory pathways in the honeybee. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 3, 16 (2009).

Rybak, J. et al. The digital bee brain: integrating and managing neurons in a common 3D reference system. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 4, 30 (2010).

Hourcade, B. et al. Long-term memory shapes the primary olfactory center of an insect brain. Learn. Mem. 16, 607–615 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by an INSPIRE fellowship from the Department of Science & Technology, Govt. of India to Priyadarshini Chakrabarti; the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), Govt. of UK Darwin Initiative grant (1662) to Parthiba Basu and a research grant to Parthiba Basu and Sagartirtha Sarkar from the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), Govt. of India.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.C. carried out all field and laboratory experiments, participated in designing the study and in writing the manuscript. S.R. helped in confocal imaging. S.B. helped in conducting behavioural experiments. D.G.N. helped in SEM imaging. S.S. participated in designing the study and writing the manuscript. P.B. participated in designing the study and in writing the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Chakrabarti, P., Rana, S., Bandopadhyay, S. et al. Field populations of native Indian honey bees from pesticide intensive agricultural landscape show signs of impaired olfaction. Sci Rep 5, 12504 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep12504

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep12504

This article is cited by

-

Effects of pesticide-adjuvant combinations used in almond orchards on olfactory responses to social signals in honey bees (Apis mellifera)

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Oxidative stress and apoptosis in Asian honey bees (A. cerana) exposed to multiple pesticides in intensive agricultural landscape

Apidologie (2022)

-

Effects of the essential oil from Cymbopogon citratus on mortality and morphology of the tick Haemaphysalis longicornis (Acari: Ixodidae)

Experimental and Applied Acarology (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.