Abstract

Water saving under drought stress is assured by stomatal closure driven by active (ABA-mediated) and/or passive (hydraulic-mediated) mechanisms. There is currently no comprehensive model nor any general consensus about the actual contribution and relative importance of each of the above factors in modulating stomatal closure in planta. In the present study, we assessed the contribution of passive (hydraulic) vs active (ABA mediated) mechanisms of stomatal closure in V. vinifera plants facing drought stress. Leaf gas exchange decreased progressively to zero during drought and embolism-induced loss of hydraulic conductance in petioles peaked to ~50% in correspondence with strong daily limitation of stomatal conductance. Foliar ABA significantly increased only after complete stomatal closure had already occurred. Rewatering plants after complete stomatal closure and after foliar ABA reached maximum values did not induced stomatal re-opening, despite embolism recovery and water potential rise. Our data suggest that in grapevine stomatal conductance is primarily regulated by passive hydraulic mechanisms. Foliar ABA apparently limits leaf gas exchange over long-term, also preventing recovery of stomatal aperture upon rewatering, suggesting the occurrence of a mechanism of long-term down-regulation of transpiration to favor embolism repair and preserve water under conditions of fluctuating water availability and repeated drought events.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stomatal regulation is one of the key mechanisms allowing plants to regulate and optimize CO2 assimilation versus evaporative water loss. Under conditions of soil water limitation and/or high atmospheric evaporative demand, partial or complete stomatal closure allows plants to maintain a favorable water balance while limiting the carbon gain1,2,3,4. Stomatal opening responds to several environmental and physiological factors such as light, carbon dioxide concentration, leaf-to-air vapor pressure deficit, leaf/plant water status and abscisic acid (ABA)5. However, there is currently no comprehensive model nor any general consensus among scientists, about the actual contribution and relative importance of the above factors in modulating stomatal closure in planta.

When water availability becomes limiting for plant physiological processes, stomatal closure acts as an early response buffering the drop of xylem water potential and the consequent risk of massive xylem embolism and catastrophic hydraulic failure6,7. Salleo et al.8 have reported that the onset of partial stomata closure in transpiring Laurus nobilis L. plants shows temporal coincidence with stem water potential values approaching the cavitation threshold, as revealed by the concurrent recording of ultrasound acoustic emissions produced by stems and leaves9. Taking into account that stomatal conductance to water vapour is generally co-ordinated with liquid phase hydraulic conductance of the soil-to-leaf pathway10,11,12, these findings have suggested that stomatal aperture is primarily modulated by hydraulic signals13,14. On the other hand, several studies have stressed the prominent role played by ABA production/accumulation in modulating stomatal closure15,16,17,18. ABA is thought to be synthesized under water stress conditions either at the root or leaf level and it would lead to the depolarization of guard cell membranes triggering osmotic ion efflux and the loss of guard cell turgor19,20,21,22,23.

Recently, Brodribb and McAdam24 suggested that stomatal closure under leaf water deficit has evolved from a passive hydraulic process mediated by water potential changes to an active process controlled by the extrusion of anions from guard cells. In support to this view, the ancient lineages of lycophytes and ferns lack of active control mechanism to modulate stomatal closure24, while in the gymnosperm Metasquoia glyptostroboides ABA effect is additive to the passive hydraulic influence on stomatal closure25.

In some angiosperm species, a lack of correlation between changes in foliar ABA and onset of stomatal closure has been reported26,27,28,29. Vitis vinifera is considered as a model species for studying responses to drought stress of woody crops30. In this species, large increases in foliar ABA have been reported under drought stress conditions. On this basis, ABA was suggested to be a major factor inducing stomatal closure in grapevine31,32,33,34. Different levels of foliar ABA accumulation were also suggested to underlie different stomatal behaviours in V. vinifera cultivars displaying near-isohydric or anisohydric hydraulic strategies35. However, recent studies have reported that near-isohydric cultivars and anisohydric cultivars also display different vulnerabilities to xylem cavitation and it has been suggested that the different stomatal behaviour of grapevine genotypes under water limitation might indeed be primarily related to their different hydraulic vulnerabilities, tailoring to ABA production and accumulation patterns a secondary role36. Outcomes of these research efforts suggest that stomatal closure in grapevine might be induced by a combination and/or an additive effects of hydraulic (water potential-mediated) and chemical (ABA-mediated) mechanisms. While in vitro ABA supply to leaves causes a rapid stomata closure19,33,37,38, it is not clear whether ABA accumulation in the leaf in planta is actually the trigger of stomata closure or just an additive signal involved in the long-term maintenance of stomatal closure under prolonged drought and/or under the initial phases of post-drought recovery. Indeed, studies on other species reported that stomatal behavior after drought is likely influenced by a combination of hydraulic and non-hydraulic factors25,39.

The aim of the present study was to determine the incidence of passive (hydraulic) and active (ABA mediated) mechanisms of stomatal closure in V. vinifera plants facing drought stress and to determine which is the signal triggering stomatal closure when vines are exposed to limiting water conditions. Our hypothesis was that in V. vinifera stomatal closure is primarily triggered by water potential decrease and coordinated with xylem vulnerability to embolism formation, with leaf ABA content eventually increasing after severe reduction of stomatal conductance to prevent sudden stomatal reopening upon transient plant rehydration. In this study we used Sangiovese and Montepulciano, two of the most important grapevine cultivars, that are considered anisohydric and isohydric, respectively.

Results

Soil water content (Θw) decreased progressively during the period when drought was imposed (Fig. 1). Two heavy rain (>50 mm) events occurred during the experiment (on the afternoon of day 4 and in the late morning of day 12) and partial soil water content recovery occurred in particular on day 4. The minimum values of Θw recorded were between 0.05 and 0.07 m3 m−3. No significant differences were observed between the two cultivars in terms of soil water content except on day 16. Pre-dawn water potential was similar in the two cultivars during the first 7 days of the experiment (Fig. 2A). From day 8 until the end of the experiment, Sangiovese had slightly lower Ψpd than Montepulciano and in days 8, 11, 12 and 15 the difference recorded was statistically significant (P < 0.05). Midday stem water potential (Ψmd) decreased progressively during the experiment and was lower in Sangiovese than in Montepulciano excluding days 4, 6, 7, 9 and 11 when the difference was not significant, or days 10 and 12 when Sangiovese had significantly higher Ψmd than Montepulciano (Fig. 2B).

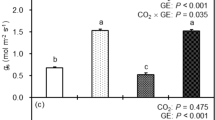

Stomatal conductance (gs) measured at midday decreased during the experiment showing a similar trend between cultivars (Fig. 3A). In more detail, the largest gs decrease occurred between days 5 and 8 when stomatal conductance dropped from about 0.130 mol m2 s−1 to 0.008 mol m2 s−1 in both cultivars. Net assimilation (An) rates followed a pattern similar to gs (Fig. 3B), yet over the first days of the experiment Montepulciano had higher assimilation rates than Sangiovese (days 1 and 2), whereas in the second part of the experiment, when gs was limited and stem water potential decreased (after day 7), Montepulciano and Sangiovese had similar net assimilation values. Foliar ABA remained constant (mean values per cultivar were not significant, P > 0.05, ANOVA) from day 1 until day 8 (Fig. 3C). On day 9, Foliar ABA increased about 3 fold in both cultivars and in Sangiovese it continued to rise until day 11, when foliar ABA peaked to a value almost 6 fold higher as compared to initial values.

Stomatal conductance and net assimilation rates showed a faster decline at higher Ψmd (i.e. less negative) in Montepulciano than in Sangiovese (Fig. 4A). In both cultivars, gs (Sangiovese R2 = 0.75 P < 0.001; Montepulciano R2 = 0.83 P < 0.001 ANOVA) and An (Sangiovese R2 = 0.90 P < 0.001; Montepulciano R2 = 0.87 P < 0.001 ANOVA) were significantly correlated to Ψmd. In particular, gs started to decline in Montepulciano at Ψmd < −0.7 MPa and reached values close to zero at Ψmd < −1.1 MPa, while, in Sangiovese, gs started to decline at Ψmd < −1.0 MPa and reached values close to zero at Ψmd < −1.5 MPa. Similar trends were observed in leaf An in both cultivars, with Montepulciano displaying a steeper reduction of An at progressively lower Ψmd than Sangiovese (Fig. 4B).

Although gs was correlated with foliar ABA by an exponential correlation (Sangiovese, y = 0.18 × e−0.66x, R2 = 0.48 P < 0.001; Montepulciano y = 0.14 × e−0.67x, R2 = 0.42 P < 0.001), there was no significant correlation between gs and foliarABA at gs > 0 (Sangiovese R2 = 0.09, P = 0.20; Montepulciano R2 = 0.11, P = 0.15) (Fig. 5).

Stomatal conductance vs leaf [ABA] in Sangiovese (y = 0.18 × e−0.66x, R2 = 0.48, P < 0.001) and Montepulciano (y = 0.14 × e−0.67x, R2 = 0.42, P < 0.001) vines measured at midday during the experiment.

The insert depict stomatal conductance (gs) vs foliar ABA per gs > 0 in Sangiovese (R2 = 0.09, P = 0.20) and Montepulciano (R2 = 0.11, P = 0.15).

Diurnal course of Ψstem, gs and foliarABA progressively changed depending on water stress severity (Fig. 6). On day 2, Ψstem decreased from 4:00 am to 1:00 pm and remained approximately stable until 6:00 pm. During the same day, maximum gs was measured at 9:00 AM while a progressive decrease was observed during the rest of the day. Montepulciano displayed higher gs values than Sangiovese at all daytimes except at 6:00 pm. Foliar ABA was constant over the whole day and was slightly higher in Sangiovese than in Montepulciano, although this difference was statistically significant only at 4:00 am. On day 8, Ψstem decreased from −0.3 MPa and −0.5 MPa at pre-dawn (4:00 am), to −1.0 MPa and −1.2 MPa at 6:00 pm in Montepulciano and Sangiovese, respectively. Ψstem measured at 6:00 pm was slightly more negative than values measured at 1:00 pm. Montepulciano had Ψstem significantly higher than Sangiovese over the whole day. On day 8, gs was consistently lower than on day 2 and maximum gs measured at 9:00 am was below 0.1 mol m−2 s−1, while near-complete stomatal closure occurred at 1:00 pm and was maintained also at 6:00 pm. On the same day, foliar ABA was slightly higher than values recorded on day 2, although there was no difference between the measurements carried out at 4:00 am, 9:00 am and 1:00 pm on day 2 and day 8. On day 8, a consistent increase of foliar ABA was measured at 6:00 pm in both cultivars. On day 15, Ψstem decreased from −1.36 MPa and −1.58 MPa at pre-dawn (4:00 am) to −1.76 MPa and −1.8 MPa at 6:00 pm in Montepulciano and Sangiovese, respectively. In Montepulciano, Ψstem was consistently higher than in Sangiovese at any timing except for 6:00 pm. On the same date, gs was steadily close to zero in both cultivars. Foliar ABA further increased in both cultivars on day 15 compared to day 8. Although the difference was not statistically significant during the day except at midday, Sangiovese leaves had higher ABA than Montepulciano leaves on day 15.

Leaf petiole percent loss of hydraulic conductance (PLC) ranged across 20% until day 5 in both cultivars (Fig. 7). On day 6, in both cultivars, leaf petiole PLC increased to values close to 50% and remained stable until day 11. On day 12, when petiole PLC was measured immediately after rain, petiole PLC dropped to values below 20%. On this date, Montepulciano had significantly higher PLC than Sangiovese. On day 15 and 16, PLC increased again up to values similar to those measured between days 6 and 11.

Foliar ABA, as well as gs (Sangiovese R2 = 0.67 P < 0.001; Montepulciano R2 = 0.71 P < 0.001 ANOVA) and An (Sangiovese R2 = 0.79 P < 0.001; Montepulciano R2 = 0.80 P < 0.001 ANOVA), were significantly correlated with Ψleaf (Sangiovese R2 = 0.87 P < 0.001; Montepulciano R2 = 0.62 P < 0.001 ANOVA) (Fig. 8). Foliar ABA increased at water potential values at which gs was below 0.02 mol m−2 s−1 in both cultivars.

Discussion

Vitis vinifera is generally considered an anisohydric species, although intra-specific variability of stomatal behaviour under water limitation condition has been observed in different grapevine genotypes40. As also reported for other species41, progressive dehydration imposed on Sangiovese and Montepulciano vines induced physiological responses that can be conveniently divided in three successive stages (Fig. 3). At stage I, when soil water is still plenty available and not affected by the onset of drought, gas exchange rates are not influenced by water shortage. In stage II, the progressive reduction of soil available water induces partial stomatal closure and gas exchange limitation. In stage III, stomata are fully and steadily closed, gas exchange rates drop to values close to zero and leaf senescence is triggered.

Throughout stage I the vine can still extract water from soil, so that no stomatal regulation of transpiration is apparent and diurnal changes of Ψstem are mainly influenced by the plant hydraulic resistance and the atmospheric evaporative demand. In our experiment, at this stage, PLC due to embolism was negligible (<20%) and leaf net assimilation was maximized. When soil water content approached critical values (<0.1 m3 m−3) in stage II, plant water potential decreased, probably enhancing the plant capacity to extract water from the soil. Progressive drop of plant water potential, however, causes xylem pressure to drop to very negative values, thus increasing the likelihood of embolism induction in xylem vessels and consequent hydraulic failure7. Under such conditions, stomatal closure plays a key role in preventing hydraulic failure by regulating the rate of water loss and limiting the xylem pressure drop6,8,16. In our experiment, stomata started to close 6 days after the beginning of water withdrawal, concurrently with the recorded increase of PLC of leaf petioles42 that approached values close to 50%. In particular, gas exchange rates were more limited in the afternoon than in the morning, when plant water status was more favourable and PLC was likely lower due to partial nocturnal vessel refilling42,43,44. These results are consistent with the coordination between stomatal movements and PLC reported in other species: in walnut Cochard et al.45 concluded that cavitation avoidance was a physiological function associated with stomatal regulation during water stress; in douglas-fir, gs was linearly correlated with PLC46; in a study on eight tropical species Brodribb et al.47 concluded that leaf and xylem hydraulic traits are correlated with the response of stomata to Ψleaf inducing loss of xylem hydraulic conductivity; and finally, in a literature overview on 70 woody species, Klein48 concluded that stomatal sensitivity to leaf water potential strongly relates to xylem characteristics.

ABA has been frequently suggested to act as a root-to-leaf chemical signal under progressive soil drying49, but some experimental observations apparently contrasts with this view. As an example, Soar et al.50 recorded gradients in xylem and foliar ABA along shoots of V. vinifera and found that the concentrations of the hormone were higher close to the apex and decreased downwards. In our experiment, foliar ABA remained below 2 ng mg−1 dw up to the occurrence of almost complete stomata closure (8th day). A significant increase of foliar ABA occurred only after complete stomatal closure had already occurred. On day 7 foliar ABA rose by 63% (Sangiovese) and 74% (Montepulciano) in comparison with the mean foliar ABA recorded in the previous days. However, we note that these data need to be interpreted with caution, as our experimental approach cannot rule out the hypothesis that early stomatal responses are influenced by very localized increases in ABA concentration, eventually below the detection limit of bulk measurements. Moreover, our data do not exclude the possibility of very local changes in ABA uptake rate into guard cells.

In grapevine leaves fed with exogenous ABA, a similar foliar ABA increase resulted in gs reduction of about 20%33, i.e. less than the 64% and 61% reduction of gs measured in our experiment in Sangiovese and Montepulciano, respectively. Furthermore, foliar ABA was correlated with Ψleaf and increased at Ψleaf values corresponding to gs < 0.02 mol m−2 s−1, thus suggesting a potential signal inducing ABA synthesis and mediated by water potential. These data support the hypothesis of foliar ABA accumulation when stomata are nearly or completely closed. These results are consistent with those reported in some gymnosperms and other angiosperm species. As an example, in M. glyptostroboides, ABA production was triggered after leaf turgor loss and stomatal closure25. In progressively water stressed Zea mays and Sorghum bicolor, stomatal closure preceded any detectable ABA increase26, while in flooded tomato plants, bulk leaf ABA increased only after the onset of stomatal closure29. Finally, in stress adapted cotton plants (Gossypium hirsutum L.) higher levels of ABA were not correlated with stomatal response to low leaf water potentials27 and in one Populus spp. hybrid, stomatal aperture was not affected by ABA28. In our study, when stomatal conductance was plotted against foliar ABA, a significant non-linear correlation appeared (R2 = 0.47, P < 0.0001), but when non limiting (>0.05 mmol m2 s−1)51 and limiting stomatal conductance values were separately linearly regressed, no significant correlation was observed (Fig. 5). These results obtained during a relatively fast (2 weeks) dry-down experiment apparently contrast with those obtained by Speirs et al.52 on vines planted in the field subject to different irrigation treatments over the season.

Our results suggest reconsidering the role played by ABA in grapevines subjected to drought stress. Apparently, ABA played no critical role in regulating gas exchange during early onset of drought conditions, as stomatal closure was apparently triggered by xylem embolism and consequent reduction of plant hydraulic conductance and leaf turgor. After stomatal closure, ABA increased by 566% and 418% in Sangiovese and Montepulciano, respectively. These levels were well above those measured by Loveys33, who measured in ABA-fed grapevine leaves a 50% reduction of stomatal conductance reduction upon ABA increase by 366%. In our experiment, a five-fold rise appeared to be effective at constraining stomatal aperture even after recovery of plant water status. In fact, when a heavy rain event occurred on day 12, water availability in the soil increased to levels not limiting for stomatal conductance and recovery of Ψstem and refilling of embolized vessels were also recorded. Nonetheless, stomatal conductance remained close to zero and this suggests that ABA inhibited stomatal re-opening although water availability was sufficient to fuel the recovery of water potential and xylem conductance. Our results would also suggest that stomatal closure can trigger foliar ABA increase and such high levels would persist afterwards despite transient recovery of leaf water status. Stomatal behaviour patterns similar to those described here were reported in Pinus radiata and Eucalyptus pauciflora by Brodribb and McAdam24 and Martorell et al.39, respectively. On the basis of these studies and our present results, it might be speculated that this behaviour might represent an effective physiological mechanism to prevent water loss in environments where plants are exposed to the risk of periodical summer drought, in that initial drought stress could induce, via ABA accumulation, the a priori down-regulation of leaf transpiration. Furthermore, stomatal closure induced by ABA has been indicated to favour vessel refilling53 by promoting de-polymerization of starch pools stored in parenchyma cells to produce sucrose or other sugars and generate the necessary osmotic gradients driving refilling54,55. The lack of stomatal conductance recovery after re-watering at day 12, coupled with the prompt decrease of PLC, would also suggest that stomatal closure induced by ABA is an important mechanism to favour fast rehydration and the rise of xylem pressure, thus further promoting osmotic-mediated embolism recovery in the case of occasional rewatering56,57.

Tallman58 (2004) hypothesized that diurnal patterns of stomatal movement are linked to ABA fluctuations and that stomatal movements are the results of the combination of ABA catabolism early in the morning and ABA biosynthesis and import from the apoplast around guard cells after midday. In our experiment, foliar ABA was steady during the whole day when water was not limiting. When stomatal closure was observed in the late morning of day 8, foliar ABA rose only in late afternoon. When stomata were steadily closed over the day (day 15) foliar ABA was steadily higher (in comparison to day 2) over the whole day. It has to be noted that foliar ABA levels might not be representative of levels actually active in guard cells. Locally active ABA levels result from the activity of ABA transport and the intensity of ABA metabolism. Therefore, levels of ABA in guard cells, which regulate turgor and are crucial for stomatal movements, could be increased over bulk leaf levels by spatially restricted activity of ABA transporters or ABA cleaving/conjugating/deconjugating enzymes. Our experimental procedures do not allow to detect eventual ABA accumulation patterns in guard cell that could explain stomatal movements during the day, but the analytical method used in the experiment allowed to measure the active form (not conjugated) of ABA. In agreement with previous experiments carried out on almond59, our data show that there is no foliar ABA reduction during the day time when stomata are open. These results are partially in contrast with the model proposed by Tallman58.

According to Tardieu and Simonneau60 and Soar et al.35, isohydric vs anisohydric behaviour (different stomatal closure dynamics in response to water potential drop) might arise from species-specific differences in stomatal sensitivity to ABA49,61. Sangiovese and Montepulciano are considered anisohydric and near-isohydric cultivars, respectively36,62,63. In our experiment, near-isohydric Montepulciano displayed lower levels of foliar ABA during all stages of the drought stress treatment in comparison with the anisohydric Sangiovese. Furthermore, the increase of Montepulciano foliar ABA recorded in stage III was less marked than in Sangionvese. Recent experiments pointed out that xylem vulnerability to cavitation might play a key role in defining stomata behaviour in V. vinifera36 and in a wide range of other species48. In particular, Klein48 concluded that isohydric vs anisohydric behavior do not represent two distinct categories but rather two extremes in a continuum of hydraulic strategies that dictates stomatal behavior due to the strong relationship between xylem characteristics and stomatal sensitivity to leaf water potential. Our results support this hypothesis, even though they do not allow to rule out a different sensitivity of stomata to similar levels of foliar ABA in these two cultivars.

Early studies on Avena sativa leaves pointed out that leaf senescence was triggered by stomatal closure64 and that stomatal closure itself triggers ABA accumulation, so that ABA might be the proximal cause of leaf senescence65. Experiments on rice, indicated that ABA is involved in senescence regulation66. Indeed, exogenously applied ABA induces the expression of several SAGs (senescence-associated genes) in Arabidopsis thaliana67. In a recent study on A. thaliana, Zhang and Gan68 concluded that there is a unique regulatory chain controlling stomatal movement and water loss during leaf senescence. Our results are consistent with this view, also considering that Sangiovese (which showed higher foliar ABA in comparison with Montepulciano) started leaf senescence and consequent leaf abscission earlier than Montepulciano (in the last experiment day it was not possible to perform measurements on Sangiovese because of the complete abscission of primary leaves).

In conclusion, in V. vinifera passive hydraulic control of stomatal closure appears to be dominant over eventual chemical signalling at the early phases of drought stress. The increase of foliar ABA concentration after stomatal closure was apparently addressed at inhibiting stomatal opening under transient rehydration, thus favouring embolism recovery. This mechanism could be effective in reducing a priori water loss in environments where periodical severe drought frequently occurs during the vegetative season. However, grapevine might also have evolved other, more sophisticated mechanisms to tightly control local ABA activity. More studies are needed to verify this alternative hypothesis.

Materials and Methods

Plant material

The study was conducted during July 2013 on 8-year-old potted V. vinifera vines of two top-grown red Italian cultivars i.e. Sangiovese (clone VCR30) and Montepulciano (clone R7), both grafted onto 1103 Paulsen rootstock and grown in an outdoor area close to the Dept. of Agricultural, Food and Environmental Sciences of the University of Perugia (Region of Umbria, central Italy, 42°58’N, 12°24’E, elevation 405 m a.s.l.). Pots (60 liters volume) were filled with loam soil. At the end of February, each vine was pruned to retain four spurs with two buds each. All shoots were oriented upright using suitable stakes. A total number of twenty vines was used in the experiment. Ten vines per cultivar were used and initially maintained at field capacity until 7th July. Water was supplied every day at 8:00 pm. On 8th July, drought was imposed on all vines by completely suspending irrigation and covering pot surface by plastic film. The drought treatment was continued until complete leaf abscission in both cultivars.

Daily measurements of soil water content were carried out at 4:00 am by a Diviner 2000 capacitance probe (Sentek Environ Tech., Sentek Environment Technologies, Stepney, South Australia), using access tubes located in three pots per cultivar. Measurements were performed at 100 mm, 200 mm and 300 mm depths from the soil surface of the pot (400 mm high). The total soil water content (Θw) in the pot was expressed as the arithmetic mean of the measurements performed at different depths.

Gas exchange and water potential

Stomatal conductance (gs) and net assimilation (An) measurements were carried out on adult primary leaves grown between the 4th and the 10th node from the shoot base. Measurements were carried out between 4:00 am and 5:00 am, 8:00 am and 9:00 am, 12:00 am and 1:00 pm, 4:00 pm and 5:00 pm from 8th July until 23th July on one representative leaf sampled from 5 vines per cultivar using an open gas exchange system (ADC-System, LCA-3, Hoddesdon, UK) equipped with a Parkinson leaf chamber (11.2 cm2). Measurements during the daytime (8:00 am to 5 pm) were performed under saturating light conditions (PPFD > 1200 μmol photons m−2 s−1). Stem water potential (Ψstem) was measured over the same days and daytimes using a pressure chamber (Soilmoisture Corp, Santa Barbara, CA, USA). Ψstem was measured on each vine on one mature leaf that had been wrapped in plastic film and aluminum foil 2 h prior to the measurements69. Water potential values measured at 4:00 am are reported as pre-dawn water potential (Ψpd).

Foliar ABA determination

Foliar ABA was determined on three primary leaves (the same used for gas exchange measurements) per cultivar sampled from different vines between 12 a.m. and 1 p.m. from 8th July (day 1) to 23rd July (day 16). On experimental days 2, 8 and 15 (9th, 15th and 22nd July, respectively), [ABA] was determined on leaves sampled concurrently with daytimes when gas exchange measurements were performed. ABA was extracted following the procedure described by Villarò et al.70 with some modifications. Leaves used for gas exchange measurements were immediately placed in liquid nitrogen and then stored in a freezer at −80 °C. Then, the material was weighted (fresh weight) and lyophilised (LIO5P, 5Pascal, Trezzano, Italy). Lyophilised material was weighted (dry weight) and grinded (MF10, IKAlabortechnik, Staufen, Germany). Leaf material (0.1 g) was extracted with 10 ml of methanol/water (1:1 v/v, pH = 3 with formic acid) for 30 min using a ultrasonic bath. After centrifugation, the supernatant was filtered through a paper filter and the same procedure was repeated for the remaining pellet. The collected filtrates were extracted twice with dichloromethane (15 ml) and the organic phase evaporated under vacuum. The residue was dissolved to a 1 ml with acetone and water/acetonitrile (50:50 v/v, 0.1% formic acid) for the HPLC analysis. Analytical standards of (±) Abscisic acid (purity ≥ 98.5%) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, PA-grade methanol, acetone, dichloromethane and formic acid and HPLC-grade acetonitrile and water were purchased from VWR Chemicals. Analyses were performed on a Perkin-Elmer PE 200 system (Autosampler, Binary Pump and UV-VIS detector) equipped with an IB-Sil C8-HC (5 mm × 250 mm × 4.6 mm Phenomenex) column and IB-Sil C8 (5 mm × 30 mm × 4.6 mm Phenomenex precolumn) at a flow rate of 0.8 mL min−1; the injection volume was 20 μL and the detection was made at 270 nm. The mobile phase of acetonitrile/water (30:70 v/v, 0.1% formic acid) was previously filtered and degassed. The compound was identified by comparing the retention times with those of authentic reference compound. The peaks were quantified by an external standard method, using the measurements of the peak areas and a calibration curve. Stock solutions of ABA standards were prepared by diluting a solution (10 mg mL−1 in acetonitrile) to obtain a range of concentrations from 0.01 to 10 mg mL−1. The limit of detection (LOD) was 0.005 mg L−1.

Percentage loss of hydraulic conductance

Percentage loss of xylem hydraulic conductance (PLC) was measured on five petioles per cultivar harvested between 12 a.m. and 1 p.m. on each day. Petioles were cut under water from leaves inserted nearby those used for gas exchange measurements. Hydraulic conductance of petioles was measured by connecting one sample end to plastic tubing filled with a filtered (0.2 μm) 20 mM KCl solution and connected to a pressure head maintained at a pressure (P) of 6 kPa. Flow (F) was measured by collecting the fluid from the distal end in pre-weighted sponge pieces fitted in plastic tubes. Flow readings were taken over 1 min time intervals. After approximately 30 minutes, once flow was found to be steady, sample hydraulic conductance (K) was calculated as F/P and the samples were flushed at P = 0.2 MPa for 30 min, to remove eventual embolism. After flushing samples, maximum hydraulic conductance (Kmax) was measured as above.

Percentage loss of hydraulic conductance (PLC) value was calculated as:

Differences between the two genotypes were assessed using the Student’s t-test (P < 0.05). The significance of regressions was tested using Pearson Product Moment Correlation.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Tombesi, S. et al. Stomatal closure is induced by hydraulic signals and maintained by ABA in drought-stressed grapevine. Sci. Rep. 5, 12449; doi: 10.1038/srep12449 (2015).

References

Boyer, J. S. Plant productivity and environment. Science 218, 443–448 (1982).

Ciais, P. M. et al. Europe-wide reduction in primary productivity caused by the heat and drought in 2003. Nature 437, 529–533 (2005).

Franks, P. J. Passive and active stomatal control: either or both? New Phytol. 198, 325–327 (2013).

Vinya, R. et al. Xylem cavitation vulnerability influences tree species’ habitat preferences in miombo woodlands. Oecologia 173, 711–720 (2013).

Farquhar, G. D. & Sharkey, T. D. Stomatal conductance and photosynthesis. Ann. Rev. Plant Biol. 61, 561–591 (1982).

Jones, H. G. & Sutherland, R. A. Stomatal control of xylem embolism. Plant Cell Environ. 11, 111–121 (1991).

Tyree, M. T. & Sperry, J. S. Vulnerability of xylem to cavitation and embolism. Ann. Rev. Plant. Physiol. & Plant. Mol. Biol. 40, 19–38 (1989).

Salleo, S., Nardini, A., Pitt, F. & Lo Gullo, M. A. Xylem cavitation and hydraulic control of stomatal conductance in laurel (Laurus nobilis L.). Plant Cell Environ 23, 71–79 (2000).

Tyree, M. T. & Dixon, M. A. Cavitation events in Thuja occidentalis L. Ultrasonic acoustic emissions from the sapwood can be measured. Plant Physiol 72, 1094–1099 (1983).

Saliendra, N. Z., Sperry, J. S. & Comstock, J. Influence of leaf water status on stomatal response to humidity, hydraulic conductance and soil drought in Betula occidentalis. Planta 196, 357–366 (1995).

Comstock, J. Hydraulic and chemical signalling in the control of stomatal conductance and transpiration. J. Exp. Bot. 53, 195–200 (2002).

Meinzer, F. C. Co-ordination of vapour and liquid phase water transport properties in plants. Plant Cell. Env. 25, 265–274 (2002).

Nardini, A. & Salleo, S. Limitation of stomatal conductance by hydraulic traits: sensing or preventing xylem cavitation? Trees 15, 14–24 (2000).

Franks, P. J. Stomatal control and hydraulic conductance, with special reference to tall trees. Tree Physiol. 24, 865–878 (2004).

Zhang, J. & Davies, W. J. Abscisic acid produced in dehydrating roots may enable the plant to measure the water status of the soil. Plant Cell Environ. 12, 73–81 (1989).

Sauter, A., Davies, W. J. & Hartung, W. The long-distance abscisic acid signal in the droughted plant: the fate of the hormone on its way from root to shoot. J. Exp. Bot. 52, 1991–1997 (2001).

Luan, S. Signalling drought in guard cells. Plant Cell Environ. 25, 229–237 (2002).

Davies, W., Kudoyarova, G. & Hartung, W. Long-distance ABA signaling and its relation to other signaling pathways in the detection of soil drying and the mediation of the plant’s response to drought. J. Plant Growth Regul. 24, 285–295 (2005).

Mittelheuser, C. J. & Van Steveninck, R. F. M. Stomatal closure and inhibition of transpiration induced by (RS)-abscisic acid. Nature 221, 281–282 (1969).

Thiel, G., MacRobbie, E. A. C. & Blatt, M. R. Membrane transport in stomatal guard cells: the importance of voltage control. J. Membr. Biol. 126, 1–18 (1992).

Geiger, D. et al. Activity of guard cell anion channel SLAC1 is controlled by drought-stress signaling kinasephosphatase pair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 21425–21430 (2009).

Geiger, D. et al. Stomatal closure by fast abscisic acid signaling is mediated by the guard cell anion channel SLAH3 and the receptor RCAR1. Sci. Signal. 4, ra32 (2011).

Bauer, H. et al. The stomatal response to reduced relative humidity requires guard cell autonomous ABA synthesis. Curr. Biol. 23, 53–57 (2013).

Brodribb, T. J. & McAdam, S. A. M. Passive origins of stomatal control in vascular plants. Science 331, 582–585 (2011).

McAdam, S. A. M. & Brodribb, T. J. Separating Active and Passive Influences on Stomatal Control of Transpiration. Plant Physiol. 164, 1578–1586 (2014).

Beardsel, M. F. & Cohen, D. Relationships between leaf water status, Abscisic acid levels and stomatal resistance in Maize and Sorghum. Plant Physiol. 56, 207–212 (1975).

Ackerson, R. C. Stomatal response of cotton to water stress and Abscisic acid as affected by water stress history. Plant Physiol. 65, 455–459 (1980).

Furukawa, A., Park, S.-Y. & Fujinuma, Y. Hybrid poplar stomata unresponsive to changes in environmental conditions. Trees 4, 191–197 (1990).

Else, M. A., Tiekstra, A. E., Croker, S. J., Davies, W. J. & Jackson, M. B. Stomatal closure in flooded tomato plants involves Abscisic acid and chemically inidentified anti-traspirant in xylem sap. Plant Physiol. 112, 239–247 (1996).

Lovisolo, C. et al. Drought induced changes in development and function of grapevine (Vitis spp.) organs and in their hydraulic and non-hydraulic interactions at the whole plant level: a physiological and molecular update. Funct. Plant Biol. 37, 98–116 (2010).

Loveys, B. R. & Kriedemann, P. E. Internal control of stomatal physiology and photosynthesis. I. Stomatal regulation and associated changes in endogenous levels of abscisic and phaseic acids. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 1, 407–415 (1974).

Liu, W. T., Pool, R., Wenkert, W. & Kriedemann, P. E. Changes in photosynthesis, stomatal resistance and abscisic acid of Vitis labruscana through drought and irrigation cycles. Am. J. Enol. Viticult. 29, 239–246 (1978).

Loveys, B. R. Diurnal changes in water relations and abscisic acid in field-grown Vitis vinifera cultivars. III. The influence of xylem-derived abscisic acid on leaf gas exchange. New Phytol. 98, 563–573 (1984).

Loveys, B. R. & Düring, H. Diurnal changes in water relations and abscisic acid in field-grown Vitis vinifera cultivars. II. Abscisic acid changes under semiarid conditions. New Phytol. 97, 37–47 (1984).

Soar, C. J. et al. Grape vine varieties Shiraz and Grenache differ in their stomatal response to VPD: apparent links with ABA physiology and gene expression in leaf tissue. Aust. J. Grape. Wine. Res. 12, 2–12 (2006).

Tombesi, S., Nardini, A., Farinelli, D. & Palliotti, A. Relationships between stomatal behavior, xylem vulnerability to cavitation and leaf water relations in two cultivars of Vitis vinifera. Physiol. Plant. 152, 453–464 (2014).

Dodd, I. C. Abscisic acid and stomatal closure: a hydraulic conductance conundrum? New Phytol. 197, 6–8 (2013).

Trejo, C. L., Davies, W. J. & Ruiz, L. M. P. Sensitivity of Stomata to Abscisic Acid (an effect of the mesophyll). Plant Physiol. 102, 497–502 (1993).

Martorell, S., Diaz-Espejo, A., Medrano, H., Ball, M. C. & Choat, B. Rapid hydraulic recovery in Eucalyptus pauciflora after drought: linkages between stem hydraulics and leaf gas exchange. Plant Cell Environ. 37, 617–626 (2014).

Chaves, M. M. et al. Grapevine under deficit irrigation: hints from physiological and molecular data. Ann. Bot. 105, 661–676 (2010).

Braatne, J. H., Hinckley, T. M. & Stettler, R. F. Influence of soil water on the physiological and morphological components of plant water balance in Populus trichocarpa, Populus deltoides and their F1 hybrids Tree Physiol. 11, 325–339 (1992).

Zufferey, V., Cochard, H., Ameglio, T., Spring, J. L. & Viret, O. Diurnal cycles of embolism formation and repair in petioles of grapevine (Vitis vinifera cv. Chasselas). J. Exp. Bot. 62, 3885–3894 (2011).

Nardini, A., Lo Gullo, M. A. & Salleo, S. Refilling embolized xylem conduits: is it a matter of phloem unloading? Plant Sci. 180, 604–611 (2011).

Trifilò, P., Barbera, P. M., Raimondo, F., Nardini, A. & Lo Gullo, M. A. Coping with drought-induced xylem cavitation: coordination of embolism repair and ionic effects in three Mediterranean evergreens. Tree Physiol. 34, 109–122 (2014).

Cochard, H., Coll, L., Le Roux, X. & Ameglio, T. Unraveling the Effects of Plant Hydraulics on Stomatal Closure during Water Stress in Walnut. Plant Physiol. 128, 282–290 (2002).

Domec, J. C., Warren, J. M., Meinzer, F. C., Brooks, J. R. & Coulombe, R. Native root xylem embolism and stomatal closure in stands of Douglas-fir and ponderosa pine: mitigation by hydraulic redistribution. Oecologia 141, 7–16 (2004).

Brodribb, T. J., Holbrook, N. M., Edwards, E. J. & Gutiérrez, M. V. Relations between stomatal closure, leaf turgor and xylem vulnerability in eight tropical dry forest trees. Plant Cell Environ. 26, 443–450 (2003).

Klein, T. The variability of stomatal sensitivity to leaf water potential across tree species indicates a continuum between isohydric and anisohydric behaviours. Funct. Ecol. 28, 1313–1320 (2014).

Davies, W. J. & Zhang, J. Root signals and the regulation of growth and development of plants in drying soil. Ann. Rev. Plant. Physiol. Plant. Mol. Biol. 42, 55–76 (1991).

Soar, C. J., Speirs, J., Maffei, S. M. & Loveys, B. R. Gradients in stomatal conductance, xylem sap ABA and bulk leaf ABA along canes of Vitis vinifera cv. Shiraz: molecular and physiological studies investigating their source. Funct. Plant Biol. 31, 659–669 (2004).

Medrano, H., Escalona, J., Bota, J., Gulias, J. & Flexas, J. Regulation of photosynthesis of C3 plants in response to progressive drought: stomatal conductance as a reference parameter. Ann. Bot. 89, 895–905 (2002).

Speirs, J., Binney, A., Collins, M., Edwards, E. & Loveys, B. Expression of ABA synthesis and metabolism genes under different irrigation strategies and atmospheric VPDs is associated with stomatal conductance in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L. cv Cabernet Sauvignon). J. Exp. Bot. 64, 1907–1916 (2013).

Secchi, F. et al. The dynamics of embolism refilling in abscisic acid (ABA)-deficient tomato plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 359–377 (2013).

Salleo, S., Trifilò, P., Esposito, S., Nardini, A. & Lo Gullo, M. A. Starch-to-sugar conversion in wood parenchyma of field-growing Laurus nobilis plants: A component of the signal pathway forembolism repair? Funct. Plant Biol. 36, 815–825 (2009).

Secchi, F. & Zwieniecki, M. A. Sensing embolism in xylem vessels: The role of sucrose as a trigger for refilling. Plant Cell Environ. 34, 514–524 (2010).

Salleo, S., Lo Gullo, M. A., De Paoli, D. & Zippo, M. Xylem recovery from cavitation-induced embolism in young plants of Laurus nobilis: a possible mechanism. New Phytol. 132, 47–56 (1996).

Tyree, M. T., Salleo, S., Nardini, A., Lo Gullo, M. A. & Mosca, R. Refilling of embolized vessels in young stems of laurel. Do we need a new paradigm? Plant Physiol. 102, 11–21 (1999).

Tallman, G. Are diurnal patterns of stomatal movement the result of alternating metabolism of endogenous guard cell ABA and accumulation of ABA delivered to the apoplast around guard cells by transpiration? J. Exp. Bot. 55, 1963–76 (2004).

Wartinger, A., Heileimer, H., Hartung, W. & Schulze, E. D. Daily and seasonal courses of leaf conductance and abscisic acid in the xylem sap of almond trees [Prunus dulcis (Miller) D.A. Webb] under desert conditions. New Phytol. 116, 581–587 (1990).

Tardieu, F. & Simonneau, T. Variability among species of stomatal control under fluctuating soil water status and evaporative demand: modelling isohydric and anisohydric behaviours. J. Exp. Bot. 49, 419–432 (1998).

Lovisolo, C., Hartung, W. & Schubert, A. Whole-plant hydraulic conductance and root-to-shoot flow of abscisic acid are independently affected by water stress in grapevines. Funct. Plant Biol. 29, 1–8 (2002).

Palliotti, A. et al. Morpho-structural and physiological response of container-grown Sangiovese and Montepulciano cvv. (Vitis vinifera) to re-watering after a pre-veraison limiting water deficit. Funct. Plant Biol. 41, 634–647 (2014).

Merli, M. C. et al. Water use efficiency in Sangiovese grapes (Vitis vinifera L.) subjected to water stress before veraison: different levels of assessment lead to different conclusions. Funct. Plant Biol. 42, 198–208 (2015).

Thimann, K. V. & Satler, S. O. Relation between leaf senescence and stomatal closure: senescence in light. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 78, 2295–2298 (1979).

Gepstein, S. & Thimann, K. V. Changes in the abscisic acid content of oat leaves during senescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 77, 2050–2053 (1980).

Yang, J., Zhang, J., Wang, Z., Zhu, Q. & Liu, L. Abscisic acid and cytokinins in the root exudates and leaves and their relationship to senescence and remobilization of carbon reserves in rice subjected to water stress during grain filling. Planta 215, 645–52 (2002).

Weaver, L. M., Gan, S. S., Quirino, B. & Amasino, R. M. A comparison of the expression patterns of several senescenceassociated genes in response to stress and hormone treatment. Plant. Mol. Biol. 37, 455–469 (1998).

Zhang, K. & Gan, S. S. An Abscisic Acid-AtNAP Transcription Factor-SAG113 Protein Phosphatase 2C Regulatory Chain for Controlling Dehydration in Senescing Arabidopsis Leaves. Plant Physiol. 158, 961–969 (2012).

McCutchan, H. & Shackel, K. A. Stem-water potential as a sensitive indicator of water stress in prune trees (Prunus domestica L. cv. French). J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 117, 607–611 (1992).

Vilaró, F., Canela-Xandri, A. & Canela, R. Quantification of abscisic acid in grapevine leaf (Vitis vinifera) by isotope-dilution liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 386, 306–312 (2006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.T., A.N. and A.P. conceived and planned the study. S.T., T.F., M.S. and C.Z. carried out the experiment and analyzed the data. S.T. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. A.P. planted and managed the vines that were used in the study and reviewed the manuscript. A.N. and S.P. revised and edited the manuscript. A.P. and D.F. helped in the analysis of the data, revised and edited the manuscript and obtained funds to support the project.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Tombesi, S., Nardini, A., Frioni, T. et al. Stomatal closure is induced by hydraulic signals and maintained by ABA in drought-stressed grapevine. Sci Rep 5, 12449 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep12449

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep12449

This article is cited by

-

The role of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria in plant drought stress responses

BMC Plant Biology (2023)

-

Proline concentrations in seedlings of woody plants change with drought stress duration and are mediated by seed characteristics: a meta-analysis

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Is intrinsic water use efficiency independent of leaf-to-air vapor pressure deficit?

Theoretical and Experimental Plant Physiology (2023)

-

Trehalose accumulation enhances drought tolerance by modulating photosynthesis and ROS-antioxidant balance in drought sensitive and tolerant rice cultivars

Physiology and Molecular Biology of Plants (2023)

-

Exogenous Foliar Application of Methyl Jasmonate Alleviates Water-Deficit Stress in Andrographis paniculata

Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.