Abstract

Ramisyllis multicaudata is a member of Syllidae (Annelida, Errantia, Phyllodocida) with a remarkable branching body plan. Using a next-generation sequencing approach, the complete mitochondrial genomes of R. multicaudata and Trypanobia sp. are sequenced and analysed, representing the first ones from Syllidae. The gene order in these two syllids does not follow the order proposed as the putative ground pattern in Errantia. The phylogenetic relationships of R. multicaudata are discerned using a phylogenetic approach with the nuclear 18S and the mitochondrial 16S and cox1 genes. Ramisyllis multicaudata is the sister group of a clade containing Trypanobia species. Both genera, Ramisyllis and Trypanobia, together with Parahaplosyllis, Trypanosyllis, Eurysyllis, and Xenosyllis are located in a long branched clade. The long branches are explained by an accelerated mutational rate in the 18S rRNA gene. Using a phylogenetic backbone, we propose a scenario in which the postembryonic addition of segments that occurs in most syllids, their huge diversity of reproductive modes and their ability to regenerate lost parts, in combination, have provided an evolutionary basis to develop a new branching body pattern as realised in Ramisyllis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Annelids are a taxon of marine lophotrochozoans with mainly segmented members showing a huge diversity of body plans1. One of the most speciose taxa is the Syllidae, which are further well-known for their diverse reproductive modes. There are two reproductive modes in Syllidae, called epigamy and schizogamy and both modes involve strong anatomical and behavioural changes. Epigamy is considered the plesiomorphic reproductive mode. It results in significant morphological and behavioural changes in the benthic, sexually mature adults2, which undergo enlargement of anterior appendages and eyes and development of swimming notochaetae in midbody-posterior segments. Notochaetae are absent in non-reproductive syllids, which only bear neurochaetae for locomotion. Transformed individuals actively ascend to the pelagic realm where spawning occurs. After spawning, the animals usually die, though some are able to reverse these changes and go back to the benthic realm for further reproductive activity. Schizogamy, the putatively derived mode, produces reproductive individuals or stolons from newly produced posterior segments. The stolons develop eyes and their own anterior appendages, as well as special swimming (noto-) chaetae, while they maintain attached to the parental body. When they are completely mature, they are detached from the parental stock for swimming and spawning2,3,4,5. Finally, the stolons die after spawning. Meanwhile, the stock remains in the benthic realm, thereby avoiding the dangers of swimming into the pelagic zone and will be able to reproduce more than once. Schizogamy can be subdivided into scissiparity (only one stolon is developed in a reproductive cycle), or gemmiparity (several stolons are developed simultaneously during the same reproductive cycle)3,4,5. Some gemmiparous syllids, like Myrianida Milne Edwards, 1845 (a member of Autolytinae), are able to produce a series of stolons, one after another (Fig. 1A), with the last one being the most developed and the first to be detached6. Another type of gemmiparity has been described for some species of Syllinae: Trypanosyllis Claparède, 1864, Trypanobia Imajima & Hartmann, 1964 (Recently erected from subgenus to genus level) and Parahaplosyllis Hartmann-Schröder, 19907,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. These animals are able to produce numerous stolons in collateral or successive budding, i.e. growing dorsally or laterodorsally from the last segment or from several posterior most segments (Fig. 1B–D). In addition, Trypanosyllis and Trypanobia have been reported to live in a symbiotic association with other animals, like echinoderms and sponges. Among them, the genus Trypanobia is the best known symbiotic form, with species such as T. asterobia (Okada, 1933) living within the body of the sea star Luidia quinaria von Martens, 1865 and developing the stolons within the host12.

Different modes of gemmiparity in Syllidae and budding in Syllis ramosa.

A. Sequential gemmiparity in Myrianida sp. (modified after Okada, 193312); B. Colateral budding in Trypanosyllis gemmipara Johnson, 1901 (modified after Johnson, 19028); C. Collateral budding in Trypanosyllis crosslandi Potts, 1911 (modified after Potts, 19119); D. Successive budding in Trypanobia asterobia (modified after Okada, 193312); E. Development of a lateral branch in S. ramosa (drawing by MT Aguado from the holotype); F. Branches and stolon in S. ramosa (modified after McIntosh, 188520). All figures used for modifications are part of the public domain.

Remarkably, within Syllinae, two species have been described with a morphology that makes them unique among all so far ~20,000 described annelids: Ramisyllis multicaudata Glasby, Schroeder and Aguado, 2012 and Syllis ramosa McIntosh, 1879. These animals are the only two branching annelids18,19,20 and they live in strict symbiosis within sponges (Fig. 2A,B). They have one “head” but multiple branches (Fig. 2C,D); each of them goes into a canal of their host, growing within the sponge by producing new branches and enlarging the existing ones. This body pattern and biology has astonished biologists and the general public since they were first described. The feeding behaviour providing nutrition for these large syllids is unknown and it remains unclear if they prey on their host. Ramisyllis multicaudata and S. ramosa also reproduce by stolons that are developed at the end of terminal branches (Fig. 1E,F). Initial phylogenetic analyses found that R. multicaudata is related to the genera Parahaplosyllis, Trypanosyllis, Eurysyllis Ehlers, 1864 and Xenosyllis Marion & Bobretzky, 187518. These genera, together with Trypanobia, show a dorsoventrally flattened or ribbon-shaped body. The analysis performed by Glasby et al. (2012)18 only included the sequences of 16S and a fragment of the 18S, which was difficult to amplify for R. multicaudata using standard primers. However, the phylogenetic placement of this branching annelid is a prerequisite to understand the evolution and character transformations leading to this unique body plan.

A. Living sponge, Petrosia sp. with posterior ends of Ramisyllis multicaudata emerging from surface pores and moving actively on the sponge surface; B. Detail of R. multicaudata posterior ends on the surface of the sponge; C. R. multicaudata, non-type, SEM of branch points, mid-body region; D. R. multicaudata, non-type, SEM, detail of one midbody branch point. All photographs were taken by CJ Glasby and PC Schroeder by SEM with methods as described previously18.

Mitochondrial genomes are valuable sources of phylogenetically informative markers. The mitochondrial genome is, in most animals, a circular duplex molecule of DNA, approximately 13–17 kb in length, with 13 protein coding genes (nad1-6, nad4L, cox1-3, cob, atp6/8), 22 tRNAs (trnX), two rRNAs (rnS, rnL) and one AT-rich non-coding region, the control region (CR), which is related with the origin of replication21. The order of these genes is subject to several types of rearrangements, such as inversion, transposition and tandem duplication random loss, which is a duplication of several continuous genes, followed by random loss of one copy of each of the redundant genes21. The high number of combinations found in Metazoa suggests that the order of genes is relatively unconstrained22.

Mitochondrial gene order has been used for phylogenetic inference in several animal taxa at different taxonomic levels23,24. Because of high substitution rates of nucleotides and amino acids between taxa and biases in nucleotide frequencies, the usefulness of mitochondrial sequences for deep phylogenies seems to be restricted25. However, they are well suited to recover phylogenetic relationships of younger divergences25. Complete mitochondrial genomes of annelids are only available for a limited number of taxa and, as far as we know, all genes are transcribed from the same strand26. The gene order is considered as generally conserved in this taxon and most investigated annelids differ only in a few rearrangements of tRNAs, which are usually regarded as more variable21. To date, around 40 complete mitochondrial genomes have been published, representing three of the main lineages (Errantia, Sedentaria, Sipuncula) within the group27. No mitochondrial genomes have been published so far for the taxon Syllidae (Errantia).

The advent of next generation sequencing techniques has simplified the generation of mitochondrial genomes, which now can be assembled as a by-product from whole genome sequencing. Due to the high copy number of mitochondria per cell, even low coverage genome data enabled the reconstruction of complete organelle genomes28. Hence we used short read Illumina sequencing for the generation of whole genome shotgun (wgs) data for two syllid species. Based on genome assemblies we extracted the mitochondrial and, additionally, nuclear ribosomal data, for phylogenetic analysis. Based on this data, we resolve the phylogenetic relationships of R. multicaudata using a molecular phylogenetic approach and extensive taxon sampling. As initial analyses suggested a possible close relationship with the genus Trypanobia, we also generated wgs data for this taxon. Moreover, the complete mitochondrial genomes of R. multicaudata and Trypanobia sp. are compared and the derived phylogeny is used to develop an evolutionary scenario leading to a branching annelid.

Results

Phylogenetic analyses

The first noticeable result to be indicated is that the 18S sequence obtained herein from the sequencing library of Ramisyllis multicaudata does not match with the one amplified by PCR and sequenced in 2012 (Genbank Acc. n° JQ292795)18. The 18S from our genome assembly is considerably longer than those of many other syllids (>2200 bp) and shows large insertions in the V2- and V5 region. However the sequences from 16S obtained herein from the mt genome and the one already published (Genbank JQ313812) were identical. Analysing carefully the small piece of 18S sequence JQ292795 and also the sequence of its proposed sister group, Parahaplosyllis brevicirra Hartmann-Schröder, 1990 (Genbank JF903679), we found suspicious similarities with the 18S sequence of another syllid, Syllis alternata Moore, 1908 (Genbank JF903649). We consider these as possible contaminations since they were sequenced at the same time. Hence, the sequence from 18S obtained herein was used to replace the previous one (JQ292795), which together with P. brevicirra (JF903679) were excluded from the analyses of the 18S partitions.

The ML analysis of the first, most inclusive data set (large 18S, Fig. 3), shows R. multicaudata as sister to Trypanobia sp. and Trypanobia depressa (Augener, 1913) (100% bootstrap) and related to other genera, such as Trypanosyllis, Xenosyllis and Eurysyllis, the same relatives as proposed by Glasby et al. (2012)18. All these taxa are in a maximally supported clade (100% bootstrap) that shows a conspicuously long branch. In order to dismiss possible Long Branch Attraction effects (LBA) and make the alignments easier, a second group of data sets was analysed focussing on a smaller taxon sampling (the trimmed 18S, 16S and cox1, respectively). The trees for each independent analysis show congruent topologies (Supplementary Figure 1A–C). Ramisyllis multicaudata, Trypanobia sp. and T. depressa are closely related and nested in a larger clade together with Trypanosyllis, Eurysyllis, Xenosyllis, and Parahaplosyllis (16S and cox1 trimmed partitions, Supplementary Figure 1B,C). The 18S topology (Supplementary Figure 4A) reveals again a long branch for this clade, while in 16S and cox1 it is not longer than others (Supplementary Figure 1B,C). In 16S and cox1 partitions, P. brevicirra is close to its previously proposed relatives18. The combined data set (trimmed 18S + 16S + cox1) recovers R. multicaudata closely related to Trypanobia sp. and T. depressa (100% bootstrap) (Fig. 4A). The Ramisyllis-Trypanobia clade is sister to a clade containing Eurysyllis tuberculata Ehlers, 1864 and Xenosyllis scabroides San Martín, Aguado & Hutchings, 2008. Parahaplosyllis brevicirra is sister to Trypanosyllis sp. and Trypanosyllis zebra (Grube, 1860) (94% bootstrap). Trypanosyllis coeliaca Claparède, 1868 is not located within this latter group. In all analyses, the genus Trypanosyllis is paraphyletic.

A. ML tree obtained when analysing the combined trimmed data set (18S + 16S + cox1). Reproductive modes in the ribbon clade are shown. The reproductive mode found in some species is assumed for the genera they belong. Collateral budding is dubious in Trypanosyllis since the gemmiparous species might be related to any or both groups (T. zebra-Trypanosyllis sp. and T. coeliaca). B. Reproductive modes in Syllidae. Phylogenetic relationships based on the analysis of the gene 18S (Fig. 2). Reproductive modes are assumed at generic level.

Mitochondrial and nuclear genomes

The assembly of the R. multicaudata whole genome shotgun data resulted in 278,762 contigs with an N50 of 769 bp and an average GC content of 32%. The assembly of Trypanobia sp. resulted in 40,225 contigs with an N50 of 676 bp and an average GC content of 38%. As the coverage turned out to be too low for analysing k-mer abundances, an approximate genome size estimation was inferred from estimating the coverage of single copy ribosomal protein genes. Based on the average coverage of these genes we estimate a size ~500 mbp for Trypanobia sp. and a genome size of ~1500 mbp for R. multicaudata. BLAST-searches for putative contigs of the sponge host genome revealed no signs of possible contamination from host tissue, as for example due to feeding.

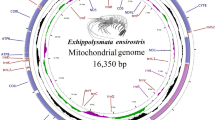

BLAST-searches identified the complete mitochondrial genomes of both investigated syllids as a single contig, which in both cases represented the longest contig of the low coverage genome assembly. The complete mitochondrial genome of R. multicaudata is 15,748 bp long and is assembled with a coverage of 105x; the one of Trypanobia sp. is 16,630 bp long and has a coverage of 70x. The two genomes are AT-rich (67% in R. multicaudata, 69% in Trypanobia sp.); A is the most common base (34% in R. multicaudata, 36% in Trypanobia sp.) and G the least common (12% and 11%, respectively). In both genomes, the coding strand has a strong skew of G vs. C (−0.31 in R. multicaudata, −0.29 in Trypanobia sp.), whereas the AT skew is positive (0.02, 0.04, respectively). Both mt genomes contain the same 37 genes as found in most other annelids and typically present in bilaterian mt genomes: 13 protein-coding genes, two genes for rRNAs and 22 genes for tRNAs (Supplementary Table 2, 3). As in the case for all annelids so far studied, all genes are transcribed from the same strand (referred to as plus-strand). However, huge differences were found in the gene arrangement of R. multicaudata and Trypanobia sp. when compared with the other known annelids26 (Fig. 5) and the putative ground pattern of Bilateria25. Additionally, none of the conserved blocks for Bilateria proposed by Bernt et al. (2013)25 have been found in the syllids.

Mitochondrial gene order in Ramisyllis multicaudata and Trypanobia sp.

Putative ground patterns for Annelida after Golombek et al. (2013)26.

The CREx analyses (Supplementary Figure 2,3) showed that the differences between Lumbricus terrestris Linnaeus, 1758 (representing Sedentaria) and Platynereis dumerilii (Audouin & Milne Edwards, 1834) (representing Errantia), each with R. multicaudata could be explained by 5 tandem duplication random losses (tdrl), respectively. Differences between L. terrestris and P. dumerilii, each with Trypanobia sp. could be explained by 4 tdrl and 1 transposition, respectively. Finally, differences between R. multicaudata and Trypanobia sp. could be explained by 1 transposition and 4 tdrl; and differences between L. terrestris and P. dumerilii by 1 transposition and 3 reversals. In addition, the matrix of a gene order similarity measure (Supplementary Table 4) reveals that the gene order between R. multicaudata and Trypanobia sp. is more different than the order of L. terrestris and P. dumerilii. Considering the order of only protein coding genes, R. multicaudata and Trypanobia sp. differ in one transposition (Fig. 5). In summary, the two mitochondrial genomes of the closely related syllids here investigated show more differences between themselves than exist between L. terrestris and P. dumerilii, the latter which might be separated by some hundred million years.

The putative control region in R. multicaudata is 702 bp in length and flanked by nad6 and trnL1 (Supplementary Table 1, Fig. 5). In Trypanobia sp., the control region is 782 bp and it is located between trnS2 and trnL1 (Supplementary Table 2, Fig. 5). In R. multicaudata, besides the control region, 27 other non-coding regions are dispersed over the whole genome, ranging from one to 147 base pairs; the largest one located between trnG and rrnL (Supplementary Table 1). In Trypanobia sp., there are 34 non-coding regions in addition to the putative control one, ranging from 1 to 265 base pairs, the largest one between trnY and trnM (Supplementary Table 2).

Start codons in protein-coding genes are highly biased towards ATG (Supplementary Table 3). In R. multicaudata, ATG is observed in 10 of 13 coding genes; other start codons are ATA and ATT. In Trypanobia sp., ATG is observed in 11 of the 13 coding genes; other start codons are ATT and TTG. In R. multicaudata, the dominant stop codon is TAA, except 1 gene ending in TAG and one putatively incomplete stop codon ending in only T (Supplementary Table 1). In Trypanobia sp., the most used stop codon is also TAA, except 1 gene were it is TAG (Supplementary Table 2). There is also a codon usage bias in both genomes (Supplementary Table 3). In general, NNG codons are the least used, while especially NNA, followed by NNT codons are the most common codon types.

The typical 22 tRNAs were found in both mt genomes. They mostly possess the common cloverleaf structure, with an acceptor arm, anticodon arm, TΨC arm, DHU arm and associated loop regions (Supplementary Figure 4,5). In R. multicaudata, the DHV stem is missing in trnC and trnR; in Trypanobia sp. the DHV stem is missing in trnR. Ramisyllis multicaudata and Trypanobia sp. have trnS1 and trnS2 with a shortened DHV stem. The sizes of the ribosomal RNAs are, in R. multicaudata, rrnL: 1008 bp, rrnS: 787 bp; and in Trypanobia sp., rrnL: 1007 bp, rrnS: 789 bp. The two genes are not separated by any tRNA, only by an intergenic spacer of 20 and 27 bp in R. multicaudata and Trypanobia sp., respectively (Supplementary Table 1, 2).

Discussion

Our phylogenetic analyses find Ramisyllis multicaudata and Trypanobia sp. within Syllidae closely related to other genera (Parahaplosyllis, Trypanosyllis, Xenosyllis and Eurysyllis) in a long branched clade (Figs 3 and 4, Supplementary Figure 1). The genera Parahaplosyllis, Trypanosyllis, Eurysyllis, Xenosyllis and Trypanobia share a distinct dorsoventrally flattened body, referred to as ribbon-like shaped29. This feature might represent a synapomorphy of this clade, though there is a reversal in R. multicaudata, which exhibits a cylindrical body pattern. This characteristic is used here to name the long branched clade including R. multicaudata as the “ribbon” clade (Fig. 4A).

The phylogenetic results shown herein are broadly congruent with a preliminary analysis18, even though the 18S sequence of R. multicaudata in that publication seems to be a contamination from another syllid species. Highly covered ribosomal sequences from the whole genome shotgun approach showed derived 18S sequences, when compared with other syllids. As such, the 18S of R. multicaudata is considerably longer, containing several long insertions. These differences may explain the failure when trying repeatedly to sequence 18S from R. multicaudata in 2012. Analyses of single gene partitions show that the 18S gene in particular greatly contributes to the observed long branches of the ribbon clade. Analyses solely based on the mitochondrial genes reveal congruent topologies, but with considerably shorter branch lengths. Interestingly, a previous study mentioned a big effort when sequencing 18S from R. multicaudata, with sequences from the host sponge recovered repeatedly18. However, BLAST searches against high copy number genes of the sponge (e.g., ribosomal genes, mitochondrial genes) did not identify any sponge related contigs in our whole genome assembly. We therefore suggest that R. multicaudata is not feeding on its host, even though the way these worms support their large body mass with nutrition remains unclear.

The analysed wgs data do not only reveal highly derived ribosomal sequences, leading to long branches in our analyses. Similarly, the mitochondrial gene order found in R. multicaudata and Trypanobia sp. also differs considerably in comparison with the gene order of Sedentaria (L. terrestris) and Errantia (P. dumerilii) (Supplementary Figure 2,3). Annelids of both these major groups analysed so far showed a remarkably conserved gene order, suggesting a common ground pattern (Fig. 5). Indeed, the differences between the gene order of Errantia, Sedentaria, the basal branching annelid lineages (represented by sipunculids) and the putative ground pattern of Spiralia (Bernt et al., 2013) are less drastic than those between any of these patterns and the analysed syllids (Fig. 5, Supplementary Table 4). In the light of these results, we conclude that the gene order in the mt genome of (Pleisto-) Annelida is more diverse than expected. Our results indicate that there might be some constraints that maintain the gene order, reflected in the relatively conserved patterns of annelid lineages; but once these constraints are violated, many changes seem possible, as revealed by the patterns in R. multicaudata and Trypanobia sp. However, since these are the first two mitochondrial genomes from syllids, it is not possible to assess if Syllidae in general, or only members of the ribbon clade including Ramisyllis and Trypanobia, show these huge differences.

Other mitochondrial genome features of R. multicaudata and Trypanobia sp. seem to be more in line with those of other annelids. Both species share with other annelids a similar pattern of codon usage bias (NNA and NNT the most common types, while NNG the least used)30. A negative GC-skew is also found in most of the mitochondrial genomes known from annelids. Regarding the tRNAs, DHU stems are lacking in many metazoan mitochondrial tRNA genes22. The sizes of the ribosomal RNAs in R. multicaudata and Trypanobia sp. are within the size range of other invertebrates including molluscs and annelids. The two genes are not separated though usually, in many animals, trnV is found in the middle; among annelids only echiurans (Urechis caupo Fisher & MacGinitie, 1928) and myzostomids (Myzostoma seymourcollegiorum Rouse & Grygier, 2005) share this condition31.

Low coverage, whole genome analyses of the two syllids allowed several interesting findings. Both taxa not only share an unusual biology, but also show derived ribosomal sequences and a strongly changed mitochondrial gene order. Rough estimations of the nuclear genome size from mapping sequence reads on putatively single copy ribosomal proteins indicates a genome size between 500 mbp and 1.5 gbp for both these taxa. In the case of Ramisyllis this size seems to be considerably larger than that of most other syllid annelids, which ranges between 100 and 500 mbp32. In summary, these results suggest a labile genomic architecture of the ancestral lineages of these taxa, putatively driven by genetic drift which could point to several past population size bottlenecks33.

The branching body pattern of Ramisyllis might be the result of the combination of processes that are closely related: post-embryonic development and regeneration. In many groups of marine annelids, segment formation occurs during both larval and juvenile development and is the result of the activity of a posterior growth zone located immediately anterior to the pygidium34. The posterior growth zone has been also referred to as segment addition zone (SAZ)35 and this latter term will be followed herein. Usually, in marine annelids with an unlimited number of segments bodies grow indeterminately, adding segments throughout their whole life35. The SAZ may contain teloblasts, which are progenitor cells that divide to produce new segments36. In these dividing cells, the cleavage plane must be perpendicular to the main axis (antero-posterior axis or A-P axis), to proliferate according to bilateral symmetry. In addition to the continuous segment formation, many groups within annelids are able to regenerate lost segments. Posterior regeneration processes imply the generation of a new SAZ36. On the molecular level, gene expression during adult growth and regeneration shows several similarities, suggesting a shared mechanism37,38. Interestingly, the occasional occurrence of annelids with two tails have been recorded both in nature, and, more frequently, in worms in which regeneration has been studied experimentally39,40,41,42. These aberrant forms might be the result of punctual “mistakes” or induced experiments during the regeneration process; and there are no reports of these animals living further for reproductive activity. Considering the occurrence of these aberrant branching forms, branching in Ramisyllis might be the result of a similar unknown event, which could have been established as a regular growth pattern.

Ramisyllis is a member of Syllidae, which might suggest that an additional process could be involved. Syllids are animals with a high capacity of regeneration of lost parts; they can regenerate anteriorly as well as posteriorly and they show a derived mode of reproduction called schizogamy that involves this regeneration ability5,14. Schizogamy implies the ability to produce reproductive individuals or stolons from newly produced segments and also the ability to regenerate the posterior end after detachment of stolons5. The regeneration of the parental stock begins with a pygidium and a new SAZ. Therefore, the life cycle in schizogamous syllids is a combination of segment addition during adult life, reproduction and regeneration.

The recovered phylogeny shown herein (Fig. 4A,B) can be used to develop a scenario of major character transformations leading to a branched annelid species. The herein analysed R. multicaudata and Trypanobia sp. are both members of Syllinae, characterized, among other features, by a schizogamous reproductive mode. In addition they are both members of the ribbon clade, where species reproduce by gemmiparity; i.e. the development of simultaneous stolons during the same reproductive cycle3,4,5 (Fig. 4A). There is one report of Parahaplosyllis as gemmiparous16, one report of Trypanobia and several of Trypanosyllis species7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. Other species in these genera reproduce by scissiparity or their reproductive mode has not been identified yet. Additionally, it is unknown if gemmiparity and scissiparity are exclusive of each species or if a species can alternate between the two modes.

In gemmiparous species of Trypanosyllis and Parahaplosyllis the stolons are developed from the parental body through the same posterior SAZ (Fig. 1B,C). However, stolons in T. asterobia are produced by separate consecutive parental segments (Fig. 1D). This evidence implies that Trypanobia develops successive SAZ simultaneously. In both, collateral budding (in Trypanosyllis and Parahaplosyllis) and successive budding (Trypanobia), the newly produced segments are developed from each SAZ at different angles from the A-P axis, being most evident in Trypanobia (Fig. 1D). The stolon attachment to the parental stock dorsally or dorsolaterally from the stock might suggest that the cleavage plane of division in the proliferating cells is somehow rotated; however, this hypothetical process is completely unknown to date.

A similar process might be responsible for development of the body pattern in R. multicaudata, since the asymmetrical branches in its body suggest different active SAZs; however, time for proliferation might be longer and instead of producing the stolons directly from the newly produced segments, these arise only at the tip of terminal branches. Additionally, in Ramisyllis the development of SAZs is random, while in Trypanobia they are developed in successive posterior segments. In Ramisyllis, branches occur asymmetrically and laterally from the A-P main axis. The reproductive mode of R. multicaudata and S. ramosa could be also considered a particular type of gemmiparity, since they are able to produce several stolons simultaneously; at the tip of terminal branches of its body18,19,20 (Figs 1F and 2A,B).

Summarizing all these observations and assuming that the reproductive modes found in some species is representative for the genera they belong, a possible scenario might be proposed in which an ancestor of the ribbon clade reproduced by collateral gemmiparity (as seen in species of Parahaplosyllis and Trypanosyllis) (Fig. 1B,C). This condition could have been later modified in the ancestor of Trypanobia and Ramisyllis, which might also maintain symbiotic relationships with other organisms (Fig. 2A,B). This hypothetical ancestor might have been able to develop several simultaneous SAZs, each producing an asymmetrical branch of new segments. The newly developed segments are directly transformed into stolons in Trypanobia (Fig. 1D), or more segments are added in a growing large chain in R. multicaudata (Fig. 1E,F) and only the distal ones are transformed into stolons; the latter strategy appears to be an adaptation to life in the complex canal system of a sponge. Within the ribbon clade, gemmiparity reverses into scissiparity in Eurysyllis and Xenosyllis (Fig. 1A,B).

An alternative hypothesis may explain the branching pattern as an independent process from the schizogamous reproductive mode and hence, considering the phylogenetic results, an autopomorphy of Ramisyllis. Future comparative studies on the genetic basis of the stolonization processes and branching body patterns of these species could give further support to any of these scenarios.

Conclusions

In this study, we provide the first complete mitochondrial genomes for Syllidae and present a scenario for the evolution of the unique morphology of the branching syllid Ramisyllis multicaudata. We find that R. multicaudata and Trypanobia are sister taxa closely related to Parahaplosyllis, Trypanosyllis, Eurysyllis and Xenosyllis and herein called the ribbon clade. The two closely related investigated species reveal strongly rearranged mitochondrial gene orders, unique for annelids. Both a comparatively large nuclear genome and strongly rearranged mitochondrial genomes could indicate past population size bottlenecks as such labile genomic architectures are more likely to be driven by genetic drift. We recognize that major phenotypic changes in syllid annelids are known from experimental studies on regeneration. The combination of undetermined postembryonic addition of segments, high ability to regenerate lost parts and gemmiparity might represent the basis for the development of a branching body pattern.

Macroevolutionary questions require complex answers integrating processes from multiple scales, ranging from within genomes to among species43. The available evidence obtained in this study suggests that R. multicaudata represents an example of major phenotypic transitions occurring by saltatational evolution44,45. Future analyses unravelling the genetic basis for the development of this unique body plan will provide further evidence for or against this hypothesis and hence we will be able to discern if Ramisyllis is indeed a hopeful monster.

Materials and methods

Genome sequencing and analyses

Sample collection from Darwin Harbour (Australia) and preparation of Ramisyllis multicaudata was previously described18. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) images were taken with a Hitachi S-570 microscope. Trypanobia sp. was collected at Lizard Island (northern Great Barrier Reef, Queensland, Australia) during a Polychaete Workshop in 2013. DNA was extracted from a single individual of each R. multicaudata and Trypanobia sp. by proteinase K digestion and subsequent chloroform extraction. For Illumina sequencing, double index sequencing libraries with average insert sizes of around 300 bp were prepared as previously described46. The libraries were sequenced as 125 bp paired-end run for R. multicaudata and 96 bp paired-end run for Trypanobia sp., both on an Illumina Hi-Seq 2000. Base calling was performed with freeIbis47, adaptor and primer sequences were removed using leeHom48 and reads with low complexity and false paired indices were discarded. Raw data of all libraries were trimmed by removing all reads that included more than 5 bases with a quality score below 15. The quality of all sequences was checked using FastQC (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/, last accessed February 17th, 2015). De novo genome assemblies were conducted with IDBA-UD 1.1.04649, using an initial k-mer size of 21, an iteration size of 10 and a maximum k-mer size of 81. N50 and average GC-content of genome assemblies were evaluated using QUAST50. All sequence data were submitted to the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) sequence read archive under accession numbers SRR2006110 for R. multicaudata and SRR2006109 for Trypanobia sp. Assembled and annotated mitochondrial genomes can be found on NCBI Genbank under accession numbers KR534502 for R. multicaudata and KR534503 for Trypanobia sp. Approximate genome size was estimated by mapping reads of single copy ribosomal proteins and subsequent coverage estimation using the software segemehl under default options51. The coverage of mitochondrial genomes was estimated by mapping sequence reads back to the contig comprising the mitochondrial genome using the same software. Possible contaminations of the R. multicaudata assembly due to its sponge host species (Petrosia sp.) were searched for using blastn searches. Three high copy number genes (18S, 28S, cox1) published for Petrosia (Strongylophora) strongylata Thiele, 1903 (KF576656, KC869619) and Petrosia ficiformis (Poiret, 1789) (JX999088) served as queries.

Phylogenetic analyses

The nuclear 18S rRNA gene was retrieved from assemblies of R. multicaudata and Trypanobia sp. and was used in the phylogenetic analyses. Other terminals (Supplementary Table 1) were mostly included in previous analyses2,52,53. Two more species, Trypanobia depressa and Trypanosyllis sp. were included for the first time in these analyses; both were also collected in Lizard Island. The genes 18S, 16S and cox1 from these two species were obtained using DNA extraction, primers and amplification and Sanger based sequencing procedures as specified previously2,54. Alignments were performed using the program MAFFT55 with the iterative refinement method E-INS-i and default gap open and extension values. Several data sets were examined: 1. One set of 18S sequences from a large number of syllids (195 terminals, Supplementary Table 5); 2. Trimmed sets of the partitions 18S, 16S and cox1 with a reduced taxon sampling (51, 48 and 21, respectively) were used in order to simplify the alignments and dismiss possible Long Branch Attraction effects (LBA); 3. A combined data set of the trimmed partitions (18S + 16S + cox1) (52 terminals). Each partition (large 18S and trimmed 18S, 16S and cox1 genes) was analysed independently, as was the combined molecular trimmed data set (18S + 16S + cox1). Concatenation of partitions for the combined data set was conducted with FASconCAT56. Maximum Likelihood (ML) analyses were conducted using RAxML version 8.1.257 with the GTR + I + G model. Bootstrap support values were generated with a rapid bootstrapping algorithm for 1000 replicates in RAxML.

Mitochondrial genome annotation and analyses

AT and GC skews were determined for the complete mitochondrial genomes (plus strand) according to the formula AT skew = (A−T)/(A + T) and GC skew = (G−C)/(G + C), where the letters stand for the absolute number of the corresponding nucleotides in the sequences58. Characterization of codon usage bias was calculated with the program DAMBE559.

The mitochondrial (mt) genomes of R. multicaudata and Trypanobia sp. were annotated using the MITOS webserver60 with the invertebrate mitochondrial code (NCBI code). This server also provided the secondary structure of tRNAs and rRNAs. To compare mitochondrial gene orders, we included the complete mt genomes of the earthworm Lumbricus terrestris and the nereidid polychaete Platynereis dumerilii, downloaded from GenBank with the accession numbers NC_001673 and AF178678, respectively. These two species were chosen as representatives of the Sedentaria and Errantia respectively, the two lineages comprising most of the species diversity of Annelida27. The mt genomes of L. terrestris and P. dumerilii were also annotated using the MITOS webserver60 with the invertebrate mitochondrial code (NCBI code). Finally, all automatic annotations were manually edited. We used CREx61 to conduct pairwise comparisons of the mitochondrial gene order of R. multicaudata and Trypanobia sp. with L. terrestris and P. dumerilii, respectively. CREx determines the most parsimonious genome rearrangement scenario between the gene order of each pair of taxa including transpositions, reverse transpositions, reversals and tandem-duplication-random-loss (tdrl) events.

Note added in proof

Trypanobia (previously a subgenus of Trypanosyllis) has been recently erected to genus level62.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Aguado, M. T. et al. The making of a branching annelid: an analysis of complete mitochondrial genome and ribosomal data of Ramisyllis multicaudata. Sci. Rep. 5, 12072; doi: 10.1038/srep12072 (2015).

References

Rouse, G. & Pleijel, F. Polychaetes. (Oxford University Press, 2001).

Aguado, M. T., San Martin, G. & Siddall, M. E. Systematics and evolution of syllids (Annelida, Syllidae). Cladistics 28, 234–250 (2012).

Garwood, P. Reproduction and the classification of the family Syllidae (Polychaeta). Ophelia Supplement 5, 81–87 (1991).

Franke, H.-D. Reproduction of the Syllidae (Annelida: Polychaeta). Hydrobiologia 402, 39–55 (1999).

Fischer, A. Reproductive and developmental phenomena in annelids: a source of exemplary research problems. Hydrobiologia 402, 1–20 (1999).

Okada, Y. Stolonization in Myrianida. J. Mar. Biol. Ass. U.K. 20, 93–98 (1936).

Johnson, H. A new type of budding in annelids. Biol. Bull. 2, 336–337 (1901).

Johnson, H. Collateral budding in annelids of the genus Trypanosyllis. Am. Nat. 36, 295–315 (1902).

Potts, F. Methods of reproduction in the syllids. Fort. Zoo. 3, 1–72 (1911).

Potts, F. Stolon formation in certain species of Trypanosyllis. Q. J. Microsc. Sci. 58, 411–446 (1913).

Izuka, A. On a case of collateral budding in syllid annelid (Trypanosyllis misakiensis, n. sp.). Annot. Zool. Jpn. 5, 283–287 (1906).

Okada, Y. Two interesting syllids, with remarks on their asexual reproduction. Mem. Coll. Sci. Kyoto Imp. Univ., Ser. B 7, 325–338 (1933).

Okada, Y. La stolonisation et les caractères sexuels du stolon chez les Syllidiens Polychètes (Etudes sur les Syllidiens III). Jap. J. Zool. 7, 441–490 (1937).

Berrill, N. J. Regeneration and budding in worms. Biol. Rev. 27, 401–438 (1952).

Nogueira, J. M. d. M. & Fukuda, M. V. A new species of Trypanosyllis (Polychaeta: Syllidae) from Brazil, with a redescription of Brazilian material of Trypanosyllis zebra. J. Mar. Biol. Ass. U.K. 88, 913–924 (2008).

Alvarez-Campos, P., San Martin, G. & Aguado, M. T. A new species and new record of the commensal genus Alcyonosyllis Glasby & Watson, 2001 and a new species of Parahaplosyllis Hartmann-Schroder, 1990, (Annelida: Syllidae: Syllinae) from Philippines Islands. Zootaxa 3734, 156–168 (2013).

Çinar, M. E. A new species of Trypanosyllis (Polychaeta: Syllidae) from the Levantine coast of Turkey (eastern Mediterranean). J. Mar. Biol. Ass. U.K. 87, 451–457 (2007).

Glasby, C. J., Schroeder, P. C. & Aguado, M. T. Branching out: a remarkable new branching syllid (Annelida) living in a Petrosia sponge (Porifera: Demospongiae). Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 164, 481–497 (2012).

McIntosh, W. On a remarkably branched Syllis dredged by H.M.S. Challenger. J. Linn. Soc. Lond. 14, 720–724 (1879).

McIntosh, W. Report on the Annelida Polychaeta collected by H.M.S. Challenger during the years 1873-1876. Challenger Rep. 12, 1–554 (1885).

Sahyoun, A. H., Bernt, M., Stadler, P. F. & Tout, K. GC skew and mitochondrial origins of replication. Mitochondrion 17, 56–66 (2014).

Boore, J. L. & Brown, W. M. Mitochondrial genomes of Galathealinum, Helobdella and Platynereis: Sequence and gene arrangement comparisons indicate that Pogonophora is not a Phylum and Annelida and Arthropoda are not sister taxa. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17, 87–106 (2000).

Bleidorn, C. et al. Mitochondrial genome and nuclear sequence data support Myzostomida as part of the annelid radiation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1690–1701 (2007).

Kilpert, F., Held, C. & Podsiadlowski, L. Multiple rearrangements in mitochondrial genomes of Isopoda and phylogenetic implications. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 64, 106–117 (2012).

Bernt, M. et al. A comprehensive analysis of bilaterian mitochondrial genomes and phylogeny. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 69, 352–364 (2013).

Golombek, A., Tobergte, S., Nesnidal, M. P., Purschke, G. & Struck, T. H. Mitochondrial genomes to the rescue – Diurodrilidae in the myzostomid trap. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 68, 312–326 (2013).

Weigert, A. et al. Illuminating the base of the annelid tree using transcriptomics. Mol. Biol. Evol. 31, 1391–1401 (2014).

Botero-Castro, F. et al. Next-generation sequencing and phylogenetic signal of complete mitochondrial genomes for resolving the evolutionary history of leaf-nosed bats (Phyllostomidae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 69, 728–739 (2013).

Aguado, M. T. & San Martin, G. Phylogeny of Syllidae (Polychaeta) based on morphological data. Zool. Scr. 38, 379–402 (2009).

Jennings, R. M. & Halanych, K. M. Mitochondrial Genomes of Clymenella torquata (Maldanidae) and Riftia pachyptila (Siboglinidae): Evidence for Conserved Gene Order in Annelida. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22, 210–222 (2005).

Mwinyi, A. et al. Mitochondrial genome sequence and gene order of Sipunculus nudus give additional support for an inclusion of Sipuncula into Annelida. BMC Genomics 10, 27 (2009).

Gambi, M. C., Ramella, L., Sella, G., Protto, P. & Aldieri, E. Variation in genome size in benthic polychaetes: Systematic and ecological relationships. J. Mar. Biol. Ass. U.K. 77, 1045–1057 (1997).

Lynch, M. The Origins of Genome Architecture. (Sinauer Assoc., 2007).

Bleidorn, C., Helm, C., Weigert, A. & Aguado, M. T. Annelida. in Evolutionary Developmental Biology of Invertebrates (ed Andreas Wanninger ) (Springer, in press).

Bely, A. E. Distribution of segment regeneration ability in the Annelida. Integr. Comp. Biol. 46, 508–518 (2006).

Balavoine, G. Segment formation in Annelids: patterns, processes and evolution. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 58, 469–483 (2014).

Novikova, E., Bakalenko, N., Nesterenko, A. & Kulakova, M. Expression of Hox genes during regeneration of nereid polychaete Alitta (Nereis) virens (Annelida, Lophotrochozoa). EvoDevo 4, 14 (2013).

Bely, A. E., Zattara, E. E. & Sikes, J. M. Regeneration in spiralians: evolutionary patterns and developmental processes. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 58, 623–634 (2014).

Andrews, E. Bifurcated annelids. Am. Nat. 26, 725–733 (1892).

Boilly, B. Induction d’un queue et des parapodes surnumeraires par deviation de l’intestin chez les Nereis. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 30, 329–343 (1973).

Combaz, A. & Boilly, B. Etude experimentale et histologique de la regeneration caudale en l’absence de chaine nerveuse chez les Nereidae (Annélides polychètes). Ann. Embryol. Morphog. 7, 171–197 (1974).

Boilly, B. & Boilly-Marer, Y. Controle de la morphogenese regeneratrice chez les annelides: cas des nereidiens (Annelides polychetes). Ann. Sci. Nat Zool. 16, 91–96 (1997).

Gould, S. The structure of evolutionary theory. (Harvard University Press, 2002).

Theißen, G. The proper place of hopeful monsters in evolutionary biology. Theory Biosci. 124, 349–369 (2006).

Jenner, R. A. Macroevolution of animal body plans: Is there science after the tree? BioScience 64, 653–664 (2014).

Meyer, M. & Kircher, M. Illumina sequencing library preparation for highly multiplexed target capture and sequencing. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2010, pdb.prot5448- (2010).

Renaud, G., Kircher, M., Stenzel, U. & Kelso, J. freeIbis: an efficient basecaller with calibrated quality scores for Illumina sequencers. Bioinformatics 29, 1208–1209 (2013).

Renaud, G., Stenzel, U. & Kelso, J. leeHom: adaptor trimming and merging for Illumina sequencing reads. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, e141 (2014).

Peng, Y., Leung, H. C. M., Yiu, S. M. & Chin, F. Y. L. IDBA-UD: a de novo assembler for single-cell and metagenomic sequencing data with highly uneven depth. Bioinformatics 28, 1420–1428 (2012).

Gurevich, A., Saveliev, V., Vyahhi, N. & Tesler, G. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 29, 1072–1075 (2013).

Hoffmann, S. et al. A multi-split mapping algorithm for circular RNA, splicing, trans-splicing and fusion detection. Genome Biol. 15, R34 (2014).

Aguado, M. T., Helm, C., Weidhase, M. & Bleidorn, C. Description of a new syllid species as a model for evolutionary research of reproduction and regeneration in annelids. Org. Divers. Evol. 15, 1–21 (2015).

Aguado, M. T. & Glasby, C. J. Indo-Pacific Syllidae (Annelida, Phyllodocida) share an evolutionary history. Syst. Biodiv. 13, 369–385 (2015).

Aguado, M. T., Nygren, A. & Siddall, M. E. Phylogeny of Syllidae (Polychaeta) based on combined molecular analysis of nuclear and mitochondrial genes. Cladistics 23, 552–564 (2007).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT Multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780 (2013).

Kück, P. & Meusemann, K. FASconCAT: Convenient handling of data matrices. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 56, 1115–1118 (2010).

Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30, 1312–1313 (2014).

Perna, N. & Kocher, T. Patterns of nucleotide composition at fourfold degenerate sites of animal mitochondrial genomes. J. Mol. Evol. 41, 353–358 (1995).

Xia, X. DAMBE5: A comprehensive software package for data analysis in molecular biology and evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 1720–1728 (2013).

Bernt, M. et al. MITOS: Improved de novo metazoan mitochondrial genome annotation. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 69, 313–319 (2013).

Bernt, M. et al. CREx: inferring genomic rearrangements based on common intervals. Bioinformatics 23, 2957–2958 (2007).

Aguado, M. T., Murray, A. & Hutchings, P. Syllidae (Annelida, Phyllodocida) from Lizard Island (Queensland, Australia). Zootaxa (in press).

Acknowledgements

We thank Michael Gerth and Robert Bücking for supporting bioinformatic analyses and Gabriel Renaud for processing the Illumina raw data. This study has been partly supported by a Geddes visiting fellowship from the Australian Museum and received funding from the DFG (BL787/5–1). Material was collected during the Polychaetes Workshop held in Lizard Island, 2013 funded by The Lizard Island Research Foundation, Permit number G12/35718.1 issued by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. We acknowledge support from the German Research Foundation (DFG) and Universität Leipzig within the program of Open Access Publishing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.T.A. and C.B. designed the study; M.T.A., C.J.G., P.C.S. and A.W. performed experiments; M.T.A. and C.B. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and contributed to the final manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Aguado, M., Glasby, C., Schroeder, P. et al. The making of a branching annelid: an analysis of complete mitochondrial genome and ribosomal data of Ramisyllis multicaudata. Sci Rep 5, 12072 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep12072

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep12072

This article is cited by

-

Morphological, histological and gene-expression analyses on stolonization in the Japanese Green Syllid, Megasyllis nipponica (Annelida, Syllidae)

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Ramisyllis kingghidorahi n. sp., a new branching annelid from Japan

Organisms Diversity & Evolution (2022)

-

Multiple introns in a deep-sea Annelid (Decemunciger: Ampharetidae) mitochondrial genome

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Monoplacophoran mitochondrial genomes: convergent gene arrangements and little phylogenetic signal

BMC Evolutionary Biology (2016)

-

On the role of the proventricle region in reproduction and regeneration in Typosyllis antoni (Annelida: Syllidae)

BMC Evolutionary Biology (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.