Abstract

Hepatitis C virus genotype 2 (HCV-2) slow responders poorly respond to 24 weeks of peginterferon (Peg-IFN) plus ribavirin (RBV). We evaluated the efficacy of extended 48-week regimen and the role of interleukin-28B (IL-28B) genotype in this clinical setting. Treatment-naïve HCV-2 patients not achieving rapid virologic response (RVR) by Peg-IFN alfa-2a 180 μg/week plus weight-based RBV (1,000–1,200 mg/day, cutoff body weight of 75 kg) were randomly assigned to receive a total duration of 48 (n = 94) or 24 (n = 93) weeks of therapy. The primary endpoint was sustained virologic response (SVR). Baseline patient characteristics to predict SVR were analyzed. Patients receiving 48 weeks of treatment had a greater SVR rate than those receiving 24 weeks of treatment (70.2% versus 46.2%, P = 0.001). Compared to patients treated for 24 weeks, the SVR rate in those treated for 48 weeks increased by 10.9% [95% CI: −5.9% to 27.7%] and 65.6% [95% CI: 44.5% to 86.7%] if they had IL-28B rs8099917 TT genotype and GT/GG genotype, respectively (interaction P = 0.002). In conclusion, 48-week treatment with Peg-IFN plus weight-based RBV provides a greater SVR rate than 24-week treatment in treatment-naïve HCV-2 patients with unfavorable IL-28B genotypes who fail to achieve RVR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is the leading cause of cirrhosis, hepatic decompensation, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and liver transplantation1. It is estimated that >185 million people with chronic HCV infection worldwide2. Although HCV genotype 2 (HCV-2) infection is relatively uncommon in North America and West Europe, it is common in East Asia2,3,4. By peginterferon (Peg-IFN) plus ribavirin (RBV) treatment, patients with HCV-2 infection have higher sustained virologic response (SVR) rates than patients with HCV genotype 1 or 4 (HCV-1/4) infection (75–95% versus 39–79%)5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. Recently, the safety and efficacy of sofosbuvir (SOF)-based therapies are excellent for HCV-2 patients, especially for those who are ineligible, intolerant or failure to prior Peg-IFN plus RBV therapy13,14,15,16. Although IFN-free regimens provide novel treatment options for these patients, the treatment costs and drug availability preclude the widespread use of these agents17.

In patients with HCV-2 infection, those achieving rapid virologic response (RVR) have comparable SVR rates by a truncated (12–16 weeks) or standard (24 weeks) duration of Peg-IFN plus RBV therapy12,18,19. However, in HCV-2 patients not achieving RVR, the benefits of improving the SVR rates by extending the treatment duration from 24 weeks to 36–48 weeks or by using weight-based (1,000–1,200 mg/day) rather than flat (800 mg/day) RBV dosages are controversial20,21,22,23. Although the SVR rates in HCV-2 patients achieving RVR by Peg-IFN plus RBV are similar regardless of interleukin-28B (IL-28B) genotypes, the role of IL-28B genotypes in HCV-2 not achieving RVR has not been fully elucidated23,24,25,26. Therefore, we aimed to compare the efficacy of Peg-IFN plus weight-based RBV for 24 or 48 weeks in HCV-2 patients not achieving RVR by Peg-IFN plus RBV and to evaluate the role of IL-28B genotypes on the viral responses in these patients.

Results

Patient Characteristics

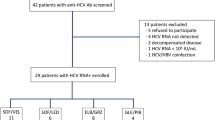

Among the 190 patients not achieving RVR by Peg-IFN plus weight-based RBV therapy, 187 were allocated to a total duration of 48-week (n = 94) or 24-week (n = 93) therapy. Seventy-four (78.7%) and 80 (86.0%) patients assigned to 48-week and 24-week therapies completed treatment and 87 (92.6%) and 88 (94.6%) patients completed 24 weeks of post-treatment follow-up to assess the SVR rates (Fig. 1). The baseline patient characteristics were comparable between the two arms (Table 1).They were slim with an average BMI of 26.3–26.7 kg/m2.Most of the patients had high baseline viral load (62–65%) and favorable IL-28B rs8099917 genotype (71–74%) and were infected with 2a subtype (68–71%). With regard to aspartate aminotransferase (AST)-to-platelet ratio index (APRI) score, 23.7–27.7% patients had a score of >2.00.

Efficacy

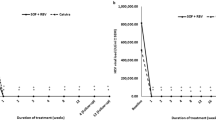

The early virologic response (EVR) (91.5% versus 88.2%, RD: 3.3% [95% CI: −5.3% to 12.0%]; P = 0.45) and the end-of-treatment virologic response (ETVR) (88.3% versus 80.6%, RD: 7.7% [95% CI: −2.7% to 18.0%]; P = 0.15) rates were comparable between the treatment arms. The SVR rate of 48-week treatment was greater than 24-week treatment (70.2% versus 46.2%, RD: 24.0% [95% CI: 10.3% to 37.7%]; P = 0.001) (Table 2). Patients with RBV cumulative exposure <60% had lower SVR rates than those with RBV cumulative exposure ≥60% in 48-week arm (77.6% versus 38.9%, P = 0.003) and 24-week arm (53.8% versus 6.7%, P = 0.001), respectively.

Subgroup Analyses for Prespecified Factors

Differences of SVR rates between patients receiving 48 and 24 weeks of treatment did not vary by baseline viral load (interaction P = 0.82), subgenotype (interaction P = 0.89), age (interaction P = 0.73), sex (interaction P = 0.94), body mass index (BMI) (interaction P = 0.26), APRI score (interaction P = 0.83) or RBV cumulative exposure (interaction P = 0.48) (Table 3). Compared to patients with favorable IL-28B rs8099917 genotype (69.2% versus 58.3%, risk difference (RD): 10.9% [95% CI: −5.9% to 27.7%]), patients with unfavorable IL-28B rs8099917 genotypes receiving 48-week therapy achieved a greater SVR rate than 24-week therapy (73.9% versus 8.3%, RD: 65.6% [95% CI: 44.5% to 86.7%]; interaction P = 0.002). The SVR rates of 48-week and 24-week treatment were similar when the patients had BMI >30 kg/m2 (52.6% versus 50.0%, RD: 2.6% [95% CI: −33.5% to 38.8%]).

Safety

The constitutional and laboratory adverse events (AEs) were similar between the two arms (Table 4). Four and 3 patients in 48-week and 24-week arms had serious AEs during treatment (4.3% versus 3.2%, RD: 1.1% [95% CI: −4.4% to 6.5%]. The AE-related withdrawal rates were 11.7% in 48-week treatment arm and 6.5% in 24-week treatment arm (RD: 5.2% [95% CI: 2.9% to 13.5%]). The rates of anemia beyond week 6 of treatment were 44.7% and 34.4% (RD: 10.3% [95% CI: −3.7% to 24.2%].

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that 48-week treatment with Peg-IFN plus weight-based RBV provided a greater SVR rate than 24-week treatment (70.2% versus 46.2%) in treatment-naïve HCV-2 patients not achieving RVR. Our results were in line with previous reports from U.S. and Japan showing that the beneficial effects of extending the treatment duration to 36–48 weeks for these patients21,22. In the N-CORE study, Shiffman et al. showed that the SVR rate of 48-week treatment was significantly greater than 24-week treatment if the patients completed a total course of treatment (73% versus 54%, P = 0.02). Instead, 48-week treatment did not provide a higher SVR rate than 24-week treatment by intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis (61% versus 52%, P = 0.19)21. Compared to patients receiving 24 weeks of treatment, the SVR rate of 48-week treatment in our study was greater than that in the N-CORE study (46.2% versus 52% for 24 weeks; 70.2% versus 61% for 48 weeks). Although patients with RBV cumulative exposure <60% had lower SVR rates than those with RBV cumulative exposure ≥60%, 48-week treatment provided greater SVR rates than 24-week treatment regardless of the grades of RBV cumulative exposure. Our findings were in line with the N-CORE study that RBV dosage and treatment duration may improve the SVR rates in HCV-2 patients not achieving RVR by reducing the relapse rates, especially for those receiving weight-based RBV for 48 weeks21.

We further analyzed if any pre-specified patient characteristics could help the health-care providers determine the optimized treatment strategies in HCV-2 patients not achieving RVR. In patients with favorable IL-28B genotype, the SVR rate of 48-week treatment was not superior to 24-week treatment. In contrast, extending the treatment duration to 48 weeks provided a superior SVR rate to standard 24 weeks of treatment if patients had unfavorable IL-28B genotypes. Similar results were also observed among HCV-1 slow responders that only those carrying unfavorable IL-28B genotypes could benefit from extended therapy to 72 week27. However, Yamaguchi et al. showed that regardless of treatment duration, the IL-28B genotypes did not affect the SVR rates in these patients. The discrepancy of the results may be reasoned by the design of the studies. Whereas we randomized 187 patients as an 1:1 ratio to maximize the power of the study, Yamaguchi et al. allowed 59 patients 24 (n = 40) or 48 (n = 19) weeks of treatment on patients’ preference, which might introduce selection bias and result in insufficient power to discriminate the effects of extended duration of therapy23.

In Asian HCV-2 patients where the prevalence rate of favorable IL-28B genotype is high, 24-week treatment would be sufficient to provide an overall SVR rate of 58.3% for these patients26. In HCV-2 patients of non-Asian ancestry where the prevalence rate of favorable IL-28B genotype is relatively low, the patients may extend the treatment duration to 48 weeks to secure the high SVR rate (73.9%) or may switch to sofosbuvir-based therapies if they were intolerable or unwilling to receiving continuous Peg-IFN plus RBV therapy in countries where sofosbuvir is available13,14,15,16.

The EASL clinical practice guideline and the expert’s opinions recommended that HCV-2 patients with cirrhosis and with BMI >30 kg/m2 should receive 24–48 weeks of Peg-IFN plus RBV regardless of RVR17,28. In contrast to the improved SVR rates of 48-week treatment irrespective of the severity of hepatic fibrosis, extending the treatment duration to 48 weeks would be beneficial to our patients with BMI ≤30 kg/m2. On the basis of our findings, HCV-2 patients with IL-28B favorable genotype or with BMI >30 kg/m2 should not receive extended duration of dual therapy if they failed to achieve RVR.

With regard to the safety, our data showed that although the AE-related withdrawal rates were greater in 48-week treatment arm than in 24-week treatment arm, the constitutional and laboratory AE rates were comparable between two arms and the serious AE rates were low in both arms. The health care providers can safely treat these patients for 24 or 48 weeks based on IL-28B genotypes, but care must be taken to keep the RBV cumulative exposure ≥60% to secure the SVR rates5,6,7,8,9,20,21,22,23.

Although we demonstrated that the SVR rate of 48-weeks treatment with Peg-IFN plus weight-based RBV was greater than that of 24-weeks of treatment. Several limitations existed. First, the effect of IL-28B genotypes on SVR was not prospectively randomized to analysis, which might cause observer bias. However, the distributions of IL-28B genotypes between the two treatment arms were similar, which minimized the potential errors of our findings. Second, the diagnosis for fibrosis and cirrhosis was based on APRI and not on liver histology.

In conclusion, 48-week treatment with Peg-IFN plus weight-based RBV provides a greater SVR rate than 24-week treatment for treatment-naïve HCV-2 patients not achieving RVR, especially for those with unfavorable IL-28B genotypes. HCV-2 patients with favorable IL-28B genotype may receive 24 weeks of treatment without compromising the SVR rates.

Methods

Patients

From 2007 to 2013, treatment-naïve patients with HCV-2 infection who were aged ≥18 years and had serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level ≥upper limit of normal (ULN) who failed to achieve RVR by Peg-IFN plus RBV were consecutively enrolled in the Tailored Regimens of Peginterferon alfa-2a and Ribavirin for Genotype 2 Chronic Hepatitis C Patients (TARGET-2) trial in 8 academic centers in Taiwan. Chronic HCV infection was defined as presence of anti-HCV antibody (Abbott HCV EIA 3.0, Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, Illinois, USA) and HCV RNA (Cobas TaqMan HCV Test v2.0, Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany, limit of detection: 15 IU/mL) for ≥6 months. HCV-2 infection was confirmed by reverse hybridization assay (Versant HCV Genotype 2.0 assay, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Illinois, USA)29.

Before receiving treatment, patients were excluded if they had anemia (hemoglobin levels <13 g/dL for men or <12 g/dL for women), neutropenia (neutrophil count <1.5 × 109 cells/L), thrombocytopenia (platelet count <90 × 109 cells/L), non HCV-2 infection, hepatitis B virus (HBV) or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) co-infection, daily alcohol consumption >20 g, serum albumin level <35 g/L, serum bilirubin level ≥1.5 times ULN, serum AST or ALT level ≥10 times ULN, serum creatinine level ≥1.5 times ULN, decompensated cirrhosis, autoimmune liver diseases, neoplastic diseases, immunosuppressive therapy, drug abuse, pregnancy, poorly controlled autoimmune diseases, cardiopulmonary diseases, neuropsychiatric diseases and diabetes mellitus with retinopathy or were unwilling to receive contraception during the study period.

The protocol was approved by Taiwan Joint Institutional Review Board and was conducted in accordance with the principles of Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization for Good Clinical Practice. All patients provided written informed consent before participation in the study.

Study Design

This was a multicenter, open-label, randomized trial. All eligible patients received combination therapy of Peg-IFN alfa-2a 180 μg/week (Pegasys, Hoffman-LaRoche, Basel, Switzerland) plus weight-based RBV 1,000–1,200 mg/day (Copegus, Hoffman-LaRoche, Basel, Switzerland; 1,000 mg/day for patients weighted <75 kg and 1,200 mg/day for patients weighted ≥75 kg). Patients who failed to achieve RVR were randomly assigned as 1:1 ratio at week 6 of treatment to receive total treatment duration of 48 or 24 weeks (Fig. 2). Randomization was computer-generated in blocks of 4 with centralized allocation and the code was secured by an independent assistant.

Baseline demographic data, hemogram, biochemical assays (serum albumin, bilirubin, AST, ALT and creatinine), serologic assays (anti-HCV, HBsAg and anti-HIV), virologic assays (HCV RNA and HCV genotype) were evaluated before enrollment. Because our study was conducted before the discovery of IL-28B genetic polymorphisms, we added the human genomic assay for IL-28B rs8099917 genotypes (ABI TaqMan allelic discrimination kit and ABI7900HT Sequence Detection System, Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies Corporation, Grand Island, New York, USA) after 2009 to evaluate the effects of these genetic polymorphisms on responses to therapy. The stage of hepatic fibrosis was assessed by APRI30. The baseline viral load was defined as high or low level at a cutoff value of 800,000 IU/mL11. Favorable IL-28B rs8099917 genotype was defined as patients with homozygous TT genotype, whereas unfavorable genotype was defined as patients with heterozygous GT or homozygous GG genotype31,32,33. Significant hepatic fibrosis (≥F2 by Metavir score) and cirrhosis (F4 by Metavir score) were defined an APRI score of >1.50 and >2.00, respectively34.

Efficacy

All patients received treatment for 48 or 24 weeks and posttreatment follow-up for 24 weeks. Serial serum HCV RNA levels were assessed at weeks 12, 24, 48 (for patients assigned to 48 weeks of treatment) of treatment and at week 24 posttreatment. The on-treatment virologic responses (including EVR and ETVR) and the posttreatment virologic response (including SVR), were defined as previously described11. Patients who failed to achieve EVR (null response at week 12), who achieved EVR but remained viremic at week 24 of treatment (null response at week 24) or who had viral breakthrough during treatment were considered nonresponders and treatment was stopped. For patients who prematurely discontinued treatment, the ETVR was assessed at the time of treatment discontinuation.

The primary endpoint was SVR, defined as undetectable serum HCV RNA 24 weeks off-therapy. Patients who were null-responsive to treatment or who had viral breakthrough during treatment were considered not to have achieved SVR, regardless of the HCV RNA data at the end of follow-up. Patients who relapsed after the treatment and who lacked the end of follow-up data to assess SVR were also considered not to have achieved SVR.

Safety

The investigators used a prespecified checklist to assess the severity and the causality of the constitutional and laboratory AEs at weeks 6 and 8 of treatment and then every 4 weeks until the end of follow-up. The severity of all AEs was graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), version 3.0. The safety summary was assessed for all patients from randomization to the last visit. Patients were withdrawn from the study if they developed serious AEs, missed receiving the allocated treatment >4 consecutive weeks, or subjectively requested to stop treatment.

The Peg-IFN alfa-2a was reduced in a stepwise dosage of 45 μg/week according to the severity of constitutional AEs. Dosages were also reduced from 180 μg/week to 90 μg/week or treatment was stopped according to laboratory AEs (the dosage was reduced to 90 μg/week if the neutrophil count was <0.75 × 109 cells/L or the platelet count was <50 × 109 cells/L; treatment was stopped if the neutrophil count was <0.50 × 109 cells/L or the platelet count was <25 × 109 cells/L). RBV was reduced in a stepwise dosage of 200 mg/day if the hemoglobin level was <10 g/dL and was stopped if the hemoglobin level was <8.5 g/dL. The erythropoiesis-stimulating agent (ESA) was not permitted in the study. Blood transfusion was permitted for patients who developed serious AEs. If the constitutional or laboratory AEs improved or resolved after dose reduction or treatment cessation, a return to the lowest dosage of the study medications was permitted.

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed by Statistical Program for Social Sciences (SPSS 17.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). On the basis of the assumption that the SVR rate was 53% for patients who received 24 weeks of treatment, we estimated that a total of 182 patients would provide 90% power to detect an absolute increase in SVR for patients who received 48 weeks of treatment of 21% points or more (2-sided α = 0.05). Patient characteristics were expressed as mean (standard deviation, SD) and percentage when appropriate.

The proportions for viral response between treatment arms were compared and reported by RD. P values for RD were obtained by the Wald asymptotic test. The subgroup analyses based on the prespecified factors to predict SVR, including baseline viral load, subgenotype, IL-28B rs8099917 genotype, age, sex, BMI, APRI score and RBV cumulative exposure, were compared by RD. The interactions between the prespecified factors and the allocated treatment were tested by the stratified Mantel-Haenszel test. All statistical tests were two-tailed and the results were statistically significant when a P value was <0.05.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Liu, C.-H. et al. Peginterferon plus weight-based ribavirin for treatment-naïve hepatitis C virus genotype 2 patients not achieving rapid virologic response: a randomized trial. Sci. Rep. 5, 11710; doi: 10.1038/srep11710 (2015).

References

Rosen, H. R. Clinical practice. Chronic hepatitis C infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 2429–2438 (2011).

Messina, J. P. et al. Global distribution and prevalence of hepatitis C virus genotypes. Hepatology. 61, 77–87 (2015).

Yu, M. L. & Chuang, W. L. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C in Asia: when East meets West. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 24, 336–345 (2009).

Liu, C. H. & Kao, J. H. Nanomedicines in the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection in Asian patients: optimizing use of peginterferon alfa. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 9, 2051–2067 (2014).

Manns, M. P. et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 358, 958–965 (2001).

Fried, M. W. et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 347, 975–982 (2002).

Hadziyannis, S. J. et al. Peginterferon-alpha2a and ribavirin combination therapy in chronic hepatitis C: a randomized study of treatment duration and ribavirin dose. Ann. Intern. Med. 140, 346–355 (2004).

McHutchison, J. G. et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b or alfa-2a with ribavirin for treatment of hepatitis C infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 361, 580–593 (2009).

Shiffman, M. L. et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin for 16 or 24 weeks in HCV genotype 2 or 3. N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 124–134 (2007).

Yu, M. L. et al. Rapid virological response and treatment duration for chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 patients: a randomized trial. Hepatology. 47, 1884–1893 (2008).

Liu, C. H. et al., Pegylated interferon-alpha-2a plus ribavirin for treatment-naive Asian patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection: a multicenter, randomized controlled trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 47, 1260–1269 (2008).

Yu, M. L. et al. A randomised study of peginterferon and ribavirin for 16 versus 24 weeks in patients with genotype 2 chronic hepatitis C. Gut. 56, 553–559 (2007).

Jacobson, I. M. et al. Sofosbuvir for hepatitis C genotype 2 or 3 in patients without treatment options. N. Engl. J. Med. 368, 1867–1877 (2013).

Lawitz, E. et al. Sofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 368, 1878–1887 (2013).

Zeuzem, S. et al. Sofosbuvir and ribavirin in HCV genotypes 2 and 3. N. Engl. J. Med. 370, 1993–2001 (2014).

Sulkowski, M. S. et al. Daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir for previously treated or untreated chronic HCV infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 370, 211–221 (2014).

European Association for Study of Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of hepatitis C virus infection. J. Hepatol. 60, 392-420 (2014).

Di Martino, V. et al. Response-guided peg-interferon plus ribavirin treatment duration in chronic hepatitis C: meta-analyses of randomized, controlled trials and implications for the future. Hepatology. 54, 789–800 (2011).

Chou, R. et al. Comparative effectiveness of antiviral treatment for hepatitis C virus infection in adults: a systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 158, 114–123 (2013).

Sato, K. et al. Response-guided peginterferon-alpha-2b plus ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C patients with genotype 2 and high viral loads. Hepatol. Res. 42, 854–863 (2012).

Shiffman, M. L. et al. Extended treatment with pegylated interferon alfa/ribavirin in patients with genotype 2/3 chronic hepatitis C who do not achieve a rapid virological response: final analysis of the randomised N-CORE trial. Hepatol. Int. 8, 517–526 (2014).

Abe, H. et al. New proposal for response-guided peg-interferon-plus-ribavirin combination therapy for chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 2 infection. J. Med. Virol. 85, 1523–1533 (2013).

Yamaguchi, Y. et al. Response-guided therapy for patients with chronic hepatitis who have high viral loads of hepatitis C virus genotype 2. Hepatol. Res. 42, 549–557 (2012).

Mangia, A. et al. An IL28B polymorphism determines treatment response of hepatitis C virus genotype 2 or 3 patients who do not achieve a rapid virologic response. Gastroenterology. 139, 821–827, 827.e1 (2010).

Sarrazin, C. et al. Importance of IL28B gene polymorphisms in hepatitis C virus genotype 2 and 3 infected patients. J. Hepatol. 54, 415–421 (2011).

Yu, M. L. et al. Role of interleukin-28B polymorphisms in the treatment of hepatitis C virus genotype 2 infection in Asian patients. Hepatology. 53, 7–13 (2011).

Scherzer, T. M. et al. Impact of IL28B on treatment outcome in hepatitis C virus G1/4 patients receiving response-guided therapy with peginterferon alpha-2a (40KD)/ribavirin. Hepatology. 54, 1518–1526 (2011).

Mangia, A. & Andriulli, A. Tailoring the length of antiviral treatment for hepatitis C. Gut. 59, 1–5 (2010).

Liu, C. H. et al. Comparison of Abbott RealTime HCV genotype II with VERSANT line probe assay 2.0 for hepatitis C virus genotyping. J. Clin. Microbiol. 53, 1754–1757 (2015).

Liu, C. H. et al. Noninvasive tests for the prediction of significant hepatic fibrosis in hepatitis C virus carriers with persistently normal alanine aminotransferases. Liver. Int. 26, 1087–1094 (2006).

Huang, C. F. et al. Interleukin-28B genetic variants in identification of hepatitis C virus genotype 1 patients responding to 24 weeks peginterferon/ribavirin. J. Hepatol. 56, 34–40 (2012).

Liu, C. H. et al. Interleukin 28B genetic polymorphisms and viral factors help identify HCV genotype-1 patients who benefit from 24-week pegylated interferon plus ribavirin therapy. Antivir. Ther. 17, 477–484 (2012).

Liu, C. H. et al. Interleukin 28B genetic polymorphisms play a minor role in identifying optimal treatment duration in HCV genotype 1 slow responders to pegylated interferon plus ribavirin. Antivir. Ther. 17, 1059–1067 (2012).

Wai, C. T. et al. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 38, 518–526 (2003).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the nurses and the patients involved in the study; Ching-Chuan Chen for central block randomization management; Hui-Ju Lin, Yu-Lin Tan, Po-Chung Liu for clinical data management; Wan-Ting Yang for host genetic analyses; Yu-Sheng Chiu, PhD for virology analyses; the 4th Core Lab and the 1st Common Laboratory of National Taiwan University Hospital, Yun-Lin Branch for instrumental and technical support. Grant Support: Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (NSC 100-2314-B-002-137-MY2). Trial registration number: ClinicalTrial.gov number, NCT00532701. The study was funded by the By National Science Council of Taiwan. The funding source had no role in the study design; the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The corresponding authors all had full access to the study data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The authors thank the TARGET-2 investigators for contributing to the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.H.L., C.F.H., W.L.C., J.H.K. and M.L.Y. designed the study; C.H.L., C.F.H., W.L.C., J.H.K. and M.L.Y. analyzed and interpreted data; C.H.L., C.F.H., C.J.L., W.L.C., J.H.K. and M.L.Y. drafted the article; C.H.L., C.F.H., C.J.L., C.Y.D., J.F.H., J.W.L., C.C.L., S.S.Y., C.L.L., T.H.S., H.C.Y., P.J.C., D.S.C., W.L.C., J.H.K., M.L.Y., C.C.C., P.H.T., M.L.H., Y.J.F., S.H.K., C.C.W., T.C.T., M.Y.H., M.L.Y. and C.F.C. revised and approved the article for important intellectual content; C.H.L., C.F.H., C.J.L., C.Y.D., J.F.H., J.W.L., C.C.L., S.S.Y., C.L.L., T.H.S., H.C.Y., P.J.C., D.S.C., W.L.C., J.H.K., M.L.Y., C.C.C., P.H.T., M.L.H., Y.J.F., S.H.K., C.C.W., T.C.T., M.Y.H., M.L.Y. and C.F.C. provided the study materials or patients; C.H.L., C.F.H., J.W.L., J.H.K. and M.L.Y. performed statistics; C.H.L., C.F.H., J.H.K. and M.L.Y. obtained funding; J.H.K. and M.L.Y. provided administrative, technical or logistic support; C.H.L., C.F.H., J.W.L., J.H.K. and M.L.Y. collected and assembled data.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Chen-Hua Liu: consultant for Abbott, Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche; on speaker’s bureau for Abbott, Roche, Bristol-Myer Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis. Jia-Horng Kao: consultant for Abbott, Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Roche; on speaker’s bureau for Abbott, Abbvie, Roche, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis; Ding-Shinn Chen: consultant for Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline; Pei-Jer Chen: consultant for Novartis and Roche; Ming-Lung Yu and Wan-Long Chuang: consultants for Merck Sharp & Dohme Abbott and Abbvie; grants support from Abbott and Roche; on speaker’s bureau from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, Merck Sharp & Dohme, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis and Gilead Sciences. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, CH., Huang, CF., Liu, CJ. et al. Peginterferon plus weight-based ribavirin for treatment-naïve hepatitis C virus genotype 2 patients not achieving rapid virologic response: a randomized trial. Sci Rep 5, 11710 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep11710

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep11710

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.