Abstract

A facile top-down/bottom-up hybrid nanofabrication process based on programmable temperature control and parallel chemical supply within microfluidic platform has been developed for the all liquid-phase synthesis of heterogeneous nanomaterial arrays. The synthesized materials and locations can be controlled by local heating with integrated microheaters and guided liquid chemical flow within microfluidic platform. As proofs-of-concept, we have demonstrated the synthesis of two types of nanomaterial arrays: (i) parallel array of TiO2 nanotubes, CuO nanospikes and ZnO nanowires and (ii) parallel array of ZnO nanowire/CuO nanospike hybrid nanostructures, CuO nanospikes and ZnO nanowires. The laminar flow with negligible ionic diffusion between different precursor solutions as well as localized heating was verified by numerical calculation and experimental result of nanomaterial array synthesis. The devices made of heterogeneous nanomaterial array were utilized as a multiplexed sensor for toxic gases such as NO2 and CO. This method would be very useful for the facile fabrication of functional nanodevices based on highly integrated arrays of heterogeneous nanomaterials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The continuous air quality monitoring in industrial or residential areas has been a very important task for decades. Accordingly, compact gas sensors based on chemoresistive semiconductor materials such as ZnO, TiO2, CuO, SnO2, In2O3 and WO3 have been widely used due to their simple design, working principle and detection scheme, as well as low costs1,2,3. Recently, gas sensors using 1D (one-dimensional) nanomaterials of metal oxides such as nanowires, nanorods and nanotubes have been actively developed since they provide high surface to volume ratio, high sensitivity and fast response speed to analyte molecules4,5. Since E. Comini, et al.6 demonstrated highly sensitive ethanol sensor using SnO2 nanobelts, 1D nanomaterial based sensors have been widely developed to detect various kinds of gases such as CO, H2, H2S, NO2, O3, etc7,8,9,10,11. Moreover, they have shown high sensitivity for the detection of sub-ppm or ppb level concentrations, depending on the types of gases11,12,13,14,15. In order to realize highly integrated sensors with 1D nanomaterials, they have to be assembled and integrated on functional electronic chips in a controlled manner. Accordingly, various integration methods have been developed such as dielectrophoresis16, optical trapping17, atomic force microscope18, microfluidic flow19 and contact printing20 for the precise alignment and assembly of 1D nanomaterials. Although these methods can assemble nanomaterials on the electrodes, they possess certain drawbacks for the economic, high-throughput manufacturing of sensor devices. The optical trapping and atomic force microscope based methods control nanomaterials with tolerance of several micrometers but require expensive setups and long process time, which is not suitable for commercial sensor fabrication. In contrast, dielectrophoresis, microfluidic flow and contact printing method can provide accurate control of position and orientation of 1D nanomaterials in shorter time and with lower cost. However, all of these methods cannot provide robust bonding between electrodes and nanomaterials since they are connected by van der Waals forces21. Therefore, additional metallization processes based on focused ion beam (FIB), electron beam lithography (EBL) and photolithography are required to provide robust electrical and mechanical bonding. R. Shen, et al. developed local thermal oxidation method, but it required multi-step processes for fabricating suspended microheater to generate high synthesis temperature and pre-deposition process for source material22. Reliable and well-controlled integration of nanomaterials become much more challenging if multiple heterogeneous nanomaterials have to be integrated within single device together, which is essential for adding multiple functionalities (eg. sensing, electronics, energy conversion, etc.) on a single microchip. Especially, the array of heterogeneous nanomaterials dramatically improves the selectivity and reliability in gas sensing applications23. Furthermore, highly integrated array of multiple gas sensing components within microscale regions can dramatically reduce both form factor and power consumption of sensor chip, which will be very useful for integrating into smartphones, wearable electronic systems and wireless nodes for sensor network. However, common methods for printing sensing materials such as drop casting24, screen printing25 and inkjet printing26 are not appropriate to realize highly integrated sensor array of heterogeneous nanomaterials due to their limited patterning resolutions.

To overcome these challenges, we propose a facile method based on the localized liquid-phase synthesis of nanomaterials with parallel supply of multiple precursor chemicals within microfluidic channel for the simultaneous and localized synthesis of multiple heterogeneous nanomaterials. Microheaters allow highly focused heat generation while parallel supply of liquid chemicals provides controlled environment for the chemical reaction. In this paper, we will explain our new method for the fabrication of highly integrated array of heterogeneous nanomaterials. Examples of nanomaterial arrays and device application to chemoresistive gas sensors will be demonstrated.

Results

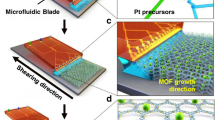

The core mechanism for this process is the localized hydrothermal synthesis of nanomaterials in a liquid precursor environment (Figure 1a). The electrical potential applied across the microheater creates localized temperature increase in a microscale region by Joule heating effect, which induces the localized synthesis of nanomaterials within liquid precursor. We can extend this process further by employing multiple microheaters for individual heating control and microfluidic channel for selective supply of different precursor solutions along the laminar flow stream. Figure 1b shows the schematics for the localized synthesis of single-type nanomaterial (hereafter, nanomaterial A) on microheater #1 in microchannel. When a precursor solution is heated above a threshold temperature, nanomaterials are synthesized by endothermic chemical reaction. The precursor solution for nanomaterial A is supplied to the inlet #1 while deionized (DI) water is supplied in other inlets. At the same time, an electrical bias is applied across microheater #1 for the Joule heating. As a consequence, hydrothermal synthesis of nanomaterial A occurs only on the microheater #1 (hereafter, case I). The synthesis location and material can be controlled by selecting heated zone and precursor solution. As shown in Figure 1c, different nanomaterials (i.e. nanomaterial B) can be synthesized on different location (i.e. on microheater #2) by supplying precursor for nanomaterial B through the inlet #2 and DI water through different inlets, while operating microheater #2 only (hereafter, case II). This method can be further extended to the simultaneous synthesis of multiplexed array of heterogeneous nanomaterials. Due to the parallel nature of the process, it is possible to synthesize not only single nanomaterial but also multiple nanomaterials at the same time. When different precursor solutions for nanomaterials A, B and C are supplied to three individual inlets and all of three microheaters generate Joule heating at the same time, three different nanomaterials A, B and C can be simultaneously synthesized at desired locations, respectively (Figure 1d) (hereafter, case III).

Principles and procedures of local synthesis of nanomaterials in microfluidic channel:

(a) localized hydrothermal synthesis of nanomaterials in precursor solution by local heat generated from microheater; (b) selective and localized synthesis of single-type nanomaterial A on microheater #1 in microfluidic channel, (c) synthesis of nanomaterial B on microheater #2 in microfluidic channel and (d) parallel synthesis of heterogeneous nanomaterial array (nanomaterial A, B and C on microheater #1, #2 and #3, respectively) in microfluidic channel.

One of the most important factors for this process is to minimize the cross-contamination between different reaction regions by diffusion or convection of precursor solutions. In order to understand the thermal and fluidic behaviors as well as the ionic diffusion between different precursor solutions, numerical simulation was conducted by using COMSOL Multiphysics® with ‘fluid flow’ and ‘chemical species transport’ models. An aqueous solution with a flow speed of 5 mm/s was supplied into a rectangular channel (width = 600 μm and height = 100 μm; Reynolds number (Re) = Udh/ν = 0.854, where U is the average flow speed, dh is the hydraulic diameter and ν is the kinematic viscosity of the fluid). The geometry of microchannel, flow speed and ionic diffusion coefficients are important factors to determine the interdiffusion and mixing between different precursor solutions. The ionic diffusion coefficient (D0) can be calculated by the following equation (1)27,28,29,30:

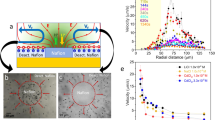

where R is the molar gas constant (R = 8.314 J/mol·K), T is the absolute temperature, F is the Faraday constant (F = 96,485 C/mol), λ is the equivalent electric conductivity and z is the valence of ion. The temperature profile of precursor solution in case I (Figure 1b) shown in Figure 2a reveals that the heat generated from microheater #1 is highly localized and not transferred to the neighboring microheaters (#2 and #3). Figure 2b shows the concentration of OH− ions, which has the highest diffusivity among all the ions contained in the precursor solution used for this process. Although there is a small disturbance by the local heat from the microheater #1, the precursor solution flows downstream without significant diffusion to the neighboring microheaters. As presented in Figure panels 2d–e, the temperature rise is also highly localized and the ionic diffusion to neighboring microheaters (#1 and #3) is insignificant in case II. The SEM images and EDS data in Figure panels 2c, f and Figure S2 prove that the synthesis of zinc oxide (ZnO) nanowires was completely localized on the selected reaction regions (i.e. on microheater #1 in case I and on microheater #2 in case II), showing an excellent agreement with the results of numerical simulations. The average diameter and length of ZnO nanowires were 50 nm and 3 μm, respectively. There are no significant differences in shape and composition of the nanowires between upper and lower regions of precursor flow stream.

Control of precursor solution flow and temperature localization during nanomaterial synthesis process in microfluidic channel:

(a) temperature profile and (b) ion concentration of precursor solution calculated by numerical simulation and (c) SEM images of synthesized nanomaterials on microheater #1 (case I); (d) temperature profile and (e) ion concentration of precursor solution calculated by numerical simulation and (f) SEM images of synthesized nanomaterials on microheater #2 (case II); The ZnO nanowires were synthesized on the target area and the results agree with numerical simulation.

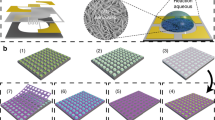

By using the same principle used for the single nanomaterial synthesis, several types of nanomaterials can be synthesized at the same time within the microchannel. In this work, we demonstrated two examples as proofs-of-concept: (i) parallel array of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanotubes, copper oxide (CuO) nanospikes and ZnO nanowires (array type I) and (ii) parallel array of ZnO nanowire/CuO nanospike hybrid nanostructures, CuO nanospikes and ZnO nanowires (array type II). Array type I is fabricated by two steps: (a) step 1 - parallel synthesis of ZnO nanowires (on microheater #1), CuO nanospikes (on microheater #2) and ZnO nanowires (on microheater #3) by simultaneous hydrothermal reaction31,32 and (b) step 2(I) - conversion of ZnO nanowires to TiO2 nanotubes on microheater #1 by liquid phase deposition (LPD) process33. In step 1, ZnO precursor solution was supplied to inlet #1 and #3 and CuO precursor solution was supplied to inlet #2, while all the microheaters (#1, #2 and #3) were heated at the same time for the localized hydrothermal synthesis (Figure 3a). In step 2(I), TiO2 precursor solution was supplied to the inlet #1 and DI water was supplied to the inlets #2 and #3. Here, no heating was required to induce the conversion of ZnO nanowires to TiO2 nanotubes during the LPD process (Figure 3b). On the other hand, the array type II requires the following two fabrication steps: (a) step 1 - parallel synthesis of ZnO nanowires (microheater #1), CuO nanospikes (microheater #2) and ZnO nanowires (microheater #3) by hydrothermal reaction and (b) step 2(II) - localized synthesis of ZnO/CuO hybrid nanostructures by decorating the pre-synthesized ZnO nanowires on microheater #1 with CuO nanospikes via localized hydrothermal reaction. In this step, CuO precursor solution was supplied only to inlet #1 while DI water was supplied to inlets #2 and #3. Also, electrical bias was applied only to microheater #1 for the localized hydrothermal synthesis of CuO nanospikes on the surface of ZnO nanowires (Figure 3c). (see the Supplementary Information for details of synthesis mechanism.)

Process flow for the fabrication of heterogeneous nanomaterial array:

(a) Step 1 - synthesis of ZnO nanowires, CuO nanospikes and ZnO nanowires on microheater #1, #2 and #3 by localized hydrothermal reaction; (b) Step 2(I) - conversion of ZnO nanowires to TiO2 nanotubes by liquid phase deposition (LPD) on microheater #1; (c) Step 2(II) - synthesis of CuO nanospikes on the surface of ZnO nanowires by localized hydrothermal reaction on microheater #1.

The experimental result of the heterogeneous nanomaterial array synthesis is presented in Figures 4 and 5. Figure 4a shows the SEM images of parallel array of ZnO nanowires, CuO nanospikes and ZnO nanowires after the step 1 for array type I. As shown in this figure, the nanomaterials were selectively synthesized on desired locations (i.e. ZnO nanowires on microheater #1, CuO nanospikes on microheater #2 and ZnO nanowires on microheater #3) with no cross-contamination between neighboring nanomaterials. The EDS data in Figure 4a (larger images shown in Figure S3a) indicates that the ZnO nanowires on microheater #1 and #3 do not contain any Cu elements and CuO nanospikes on microheater #2 do not contain any Zn elements. This can be attributed to the minimal ionic diffusion between different flow streams within microfluidic channel. After the step 2(I) (i.e. conversion of ZnO nanowires to TiO2 nanotubes), ZnO nanowires disappear and TiO2 nanotubes are observed on the microheater #1 by the LPD reaction as shown in Figure 4b. As shown in the high resolution SEM images of each synthesized nanomaterial, the average outer diameters of TiO2 nanotubes, CuO nanospikes and ZnO nanowires were approximately 100 nm, 200 nm and 50 nm, respectively and their average lengths were approximately 3 μm, 2 μm and 3 μm, respectively. The average wall thickness of TiO2 nanotubes was measured as 25 nm. As shown in the EDS spectra of synthesized TiO2 nanotubes, CuO nanospikes and ZnO nanowires, the ZnO nanowires were successfully converted to TiO2 nanotubes while neighboring CuO nanospikes and ZnO nanowires were not contaminated with the Ti element (Figure 4b; larger images shown in Figure S3b).

SEM images and EDS data of the heterogeneous nanomaterial arrays in synthesis sequence for array of TiO2 nanotubes, CuO nanospikes and ZnO nanowires:

(a) ZnO nanowire, CuO nanospike and ZnO nanowire array after step 1 and (b) TiO2 nanotube, CuO nanospike and ZnO nanowire array after step 2(I); There were no cross-contamination and damages at the nanostructures during the successive TiO2 conversion process.

SEM images and EDS data of the heterogeneous nanomaterial arrays in synthesis sequence for array of ZnO/CuO hybrid nanostructures, CuO nanospikes and ZnO nanowires:

(a) ZnO nanowire, CuO nanospike and ZnO nanowire array after step 1 and (b) ZnO/CuO hybrid nanostructure, CuO nanospike and ZnO nanowire array after step 2(II); There were no cross-contamination and damages at the nanostructures during the successive CuO nanospike synthesis process.

Figure 5 presents the synthesis result of parallel array of ZnO nanowire/CuO nanospike hybrid nanostructures, CuO nanospikes and ZnO nanowires (array type II). Figure 5a shows an array of ZnO nanowires, CuO nanospikes and ZnO nanowires, which is similar to that in Figure 4a. In the case of array type II, ZnO nanowires were coated with CuO nanospikes to form ZnO nanowire/CuO nanospike hybrid nanostructures by using step 2 (II) (Figure 5b). Here, CuO precursor solution was supplied only to inlet #1 while DI water was flown through inlets #2 and #3. At the same time, the electrical bias was applied only across microheater #1. As a consequence, CuO nanospikes were synthesized only on the surface of ZnO nanowires that were already synthesized on the microheater #1 in the previous step. No contamination or damage to the neighboring nanostructures (CuO nanospikes on microheater #2 and ZnO nanowires on microheater #3) could be observed. As shown in the high resolution SEM images of synthesized nanomaterials, the hybrid nanostructures with core ZnO nanowires and branch CuO nanospikes can be clearly observed. Here, CuO nanospikes with an average length of 300 nm and base diameter of 100 nm were uniformly grown along the ZnO nanowires that were pre-synthesized in step 1. The additional Cu peak on microheater #1 from EDS spectra in Figure 5b (larger images shown in S4b) indicates the surface decoration of ZnO nanowires with CuO nanospikes. No contamination of neighboring nanostructures (i.e. CuO nanospikes on microheater #2 and ZnO nanowires on microheater #3) can be observed in the SEM images and also be verified by the EDS spectra result.

Discussion

Two essential mechanisms for this process can be summarized as follows: (1) little cross-contamination between neighboring flow streams (eg. stream #1 and #2) within microchannel due to low Reynolds number (eg. Re = 0.854 for flow speed of 5 mm/s) and (2) localized heating of precursor solutions by Joule heating of microheaters with little heat dissipation to the neighboring regions. We could estimate the ionic diffusion during the synthesis process by numerical simulation. Figure panels 6a and b show the concentrations of Zn2+, Cu2+ and OH− ions during step 1. Table S1a summarizes the concentration of each ion at the center of each microheater. The concentrations of Zn2+ ions at the center of microheaters #1 and #3 are both 4.00 mM, while it drastically drops down to 51.99 nM at the center of microheater #2. In opposite, the concentration of Cu2+ ions is maintained at 4.00 mM at the center of microheater #2 while those at the centers of microheaters #1 and #3 are 1.138 nM and 0.9858 nM, respectively. This minimal diffusion of ions to the neighboring flow stream can be explained by the abovementioned laminar flow within microchannel. The mixing of ions between streams under laminar and uniaxial flow is purely diffusive34. The Péclet number (Pe = U·W/D, where U is the average flow speed, W is the channel width and D is the ionic diffusivity) of Zn2+, Cu2+, OH−, Ti+ and F− ions are 4267, 4202, 569, 1508 and 2034, respectively, at room temperature34,35. These values reflect that the diffusion is very slow with respect to the flow speed of the solution. Similar phenomenon can be found for the step 2(I) (i.e. local conversion of ZnO nanowires into TiO2 nanotubes on microheater #1). Figure panels 6c and d and Table S1b explain the concentrations of Ti+ and F− ions (main components of the TiO2 precursor) during this step. The molar concentrations of Ti+ and F− are 600.0 mM and 100.0 mM, respectively, at the center of microheater #1 but they rapidly drop down to 140.5 μM and 65.25 μM, respectively, at the center of microheater #2. Similar trend of negligible ionic diffusion is observed in the case of step 2(II) (i.e. local synthesis of ZnO nanowire/CuO nanospike hybrid nanostructures on microheater #1) as shown in Figure panels 6e and f. Details on the ionic diffusion can also be found in Table S1c. These simulation results verify that cross-contamination between different nanomaterials is negligible due to minimal mixing between neighboring laminar flow streams.

Numerical simulation results of ion concentrations of precursor solutions during each synthesis process:

Overview image of ion concentrations in the microchannel during (a) step 1, (c) step 2(I) and (e) step 2(II) and ion concentration-position curve on the microheater during (b) step 1, (d) step 2(I) and (f) step 2(II); The precursor solutions hardly transferred to the neighboring flow stream due to laminar flow. The concentrations of all ions (Zn2+, Cu2+, OH−, Ti+ and F−) was drastically dropped at the neighboring microheaters and these numerical simulation results agree with experimental results.

One can further decrease the ionic diffusion by controlling the flow speed of precursor liquids. Figure S5 and Table S2 show the concentration profiles and values of Zn2+ and OH− ions for different flow speeds. The profile of ionic concentrations gets steeper (i.e. higher gradient of ionic concentrations due to less diffusion) if the flow speeds are increased since the ions are flown downstream without sufficient mixing34. The concentrations of Zn2+ and OH− ions at the center of microheater #2 can be dropped to sub-pM with flow speed of over 10 mm/s and 100 mm/s, respectively. The profile of ionic concentration can be further controlled by adjusting the ratio of flow speed at each flow inlet. When the ratio of flow speed for inlet #1, #2 and #3 are changed from 1:1:1 to 1:1.5:1.5, 1:2:2 and 1:3:3 while total flow rate in the microchannel is fixed as 0.3 μL/s, the concentration profiles of both Zn2+ and OH− ions are shifted towards flow stream #1 (Figure S6a–b and Table S3a–b). When individual precursor solutions arrive at the main microchannel, the speed of the higher speed flow streams (stream #2 and #3) are decreased and that of the lower speed flow stream (stream #1) is increased due to the friction force between flow streams caused by the viscosity of the solutions. According to Bernoulli's principle considering energy loss during speed to pressure conversion, the pressure of the higher speed flow streams are higher than that of the slower speed flow stream in the main microchannel. As a consequence, the flow stream #1 is pushed towards the edge of microchannel and the concentration profile of Zn2+ and OH− ions are shifted towards the flow stream #1. We can conclude that an array of various nanomaterials can be synthesized with higher purity and position control by optimizing the concentrations and flow speeds of individual precursor solutions within microfluidic channel.

During the synthesis process, the heat from microheater is dissipated to the precursor solution by forced convection. Figure S7a shows the temperature profiles of the precursor solution along stream #1 under various flow speeds, but with a constant thermal power of 0.85 W by microheater #1. Due to the nonzero flow speed, the temperature profile is not symmetrical but more heat dissipation is created in the downstream direction. At higher flow speed, the temperature distribution becomes more asymmetric and localized near the surface of microheater. Also, since the precursor solution quickly pass through microheater for a short period, both maximum temperature and heating area are decreased as the flow speed is increased (Figure S7b). Larger heat loss makes it difficult to grow longer nanomaterials in the vertical direction at higher flow speed of precursor solution. To synthesize the nanomaterials at higher flow speed, higher power should be supplied to microheater to compensate for the larger heat loss. Figure S8a shows the top and side view SEM images of the ZnO nanowires synthesized under the same heating power (0.85 W) in the microheater but different flow speeds of precursor solution. The length of synthesized nanowires decreased with increasing flow speed as expected by the numerical simulation (Figure S8b). The average height of nanowires was 5.02, 3.52, 3.00 and 2.29 μm for flow speeds of 5, 20, 100 and 500 mm/s, respectively. The area of synthesized nanowires also decreased with increasing flow speed (2033, 1972, 1370 and 1162 μm2 of synthesis area for the flow speeds of 5, 20, 100 and 500 mm/s, respectively). Here, it should be noted that the maximum length of the synthesized nanowire bundles was not rapidly decreased as the temperature profile (Figure S7b) since considerable heat can also be transported through the ZnO nanowires whose thermal conductivity is about 80 times higher than that of aqueous solution (eg. 6.5 W/K·m for ZnO nanowire and 0.08 W/K·m for water at room temperature)36,37. Effective heat transfer through thermal conduction along the ZnO nanowires to their tips enables their longer growth. It should be noted that nanowires involved in a direct interconnection between sensing electrodes would play a major role for the electrical signal of the device. However, the contribution of other nanowires (i.e. nanowires that are not associated with a direct interconnection between sensing electrodes) cannot be ignored since many nanowires are synthesized with a slight angle deviation (±5 ~ 15°) from vertical direction forming numerous junctions with neighboring nanowires. If the length and density of synthesized nanowires are too small, the surface area for gas reaction will be small and the sensitivity of sensor will be reduced accordingly. On the other hand, if the nanowires are overly grown with excessive density and length, the advantage of 1D nanostructures will be lost. Therefore, the length and density of synthesized nanowires should be optimized, which will be investigated in the future.

Multiplexed array based sensors have attracted great interests due to their outstanding sensing performances, especially the enhanced selectivity for gas sensor applications38. Although single material based gas sensors can detect target gases, their responses are highly affected by interfering gases as well39. Multiplexed sensor arrays can greatly improve the selectivity and accuracy by analyzing multiple data collected from array of different sensing materials40. We demonstrated that two kinds of synthesized heterogeneous nanomaterial arrays (array type I and II) can be used as multiplexed gas sensor array devices. The sensors were exposed to 0.1–20 ppm of NO2 gas and 20–1000 ppm of CO gas in dry air. Here, NO2 is an oxidizing gas whereas CO is a reducing gas on the surface of metal oxide nanomaterials, thereby affecting their electrical resistances. The sensing materials were heated to operating temperature by Joule heating of the embedded microheaters. The temperatures were estimated as 300–350°C by measuring the electrical resistance of microheaters. Figure panels 7a–f show the sensor responses of TiO2 nanotubes, CuO nanospikes and ZnO nanowires under 0.1, 0.5, 1 and 2 ppm of NO2 gas and 20, 200, 500 and 1000 ppm of CO gas, respectively. Figure panels 7g–l show the sensor responses of ZnO/CuO hybrid nanostructues, CuO nanospikes and ZnO nanowires under the same concentrations of NO2 and CO gases, respectively. Here, the response was defined as the relative change of electrical resistance (S = ΔR/Rair × 100%), in which Rair represents the baseline resistance in normal air and ΔR represents the change of resistance by the exposure to target gas. As shown in Figure panels 7m–p, the resistance of n-type materials (i.e. TiO2 nanotubes and ZnO nanowires) were increased with increasing concentration of NO2 gas and decreased with increasing concentration of CO gas. On the other hand, the resistance of p-type material (i.e. CuO nanospike) was decreased with increasing concentration of NO2 gas and increased with increasing concentration of CO gas.

Multiplexed gas sensing results:

Sensing responses of TiO2 nanotube, CuO nanospike and ZnO nanowire array to (a)–(c) NO2 and (d)–(f) CO gases; and sensing responses of ZnO/CuO hybrid nanostructure, CuO nanospike and ZnO nanowire array to (g)–(i) NO2 and (j)–(l) CO gases; (m)–(p) response vs. concentration curve of two heterogeneous nanomaterial arrays to NO2 and CO gases; The resistance of n-type materials (TiO2, ZnO, ZnO/CuO) were increased under NO2 gas and decreased under CO gas. In contrast, the resistance of p-type material (CuO) was decreased under NO2 gas and increased under CO gas.

When NO2 gas molecules are adsorbed on the surface of metal oxide nanomaterials, they capture the electrons from the surface of metal oxide and form O− ions. The negatively charged oxygen ions contribute to the decrease of electron concentration in n-type materials and the increase of hole concentration in p-type materials41,42,43. In contrast, CO molecules react with adsorbed O− ions to form CO2 molecules and release the electrons back to the metal oxide materials. This reaction increases the electron concentration in n-type materials and decreases the hole concentration in p-type materials44,45,46. The gas sensing response of ZnO/CuO hybrid nanostructures was similar to those of n-type materials since the n-type ZnO nanowires worked as the base material47. However, it should be noted that the CuO nanospikes on the ZnO nanowires make p-n junctions that capture electrons and generate depletion layers. Consequently, the electrical resistance of the core structure (ZnO nanowires) is increased and the sensing characteristics is changed. The study of detailed gas sensing mechanisms of ZnO/CuO hybrid nanostructures is still ongoing and will be reported in the future.

Although we have not fully tested the sensing performances of the fabricated devices to more variety of target gases, our results provide sufficient preliminary data for the potential capability of multiplexed gas sensing. The fabricated devices can detect 0.1 ppm of NO2 and 20 ppm of CO2, which are lower concentrations than the air quality guidelines (exposure for 1 hour) by World Health Organization (WHO)48,49. This performance is comparable to other nanomaterial based NO2 and CO gas sensors7,10,50,51,52,53. Also, by using the combinations of multiple n-type and p-type semiconductor nanomaterials, we could obtain multiple data for target gases, which can be readily used for the sensor the data analysis process such as principal component analysis54.

In conclusion, we have developed a facile top-down/bottom-up hybrid nanofabrication method for the controlled synthesis of heterogeneous nanomaterial array. The method is based on localized, parallel liquid-phase reaction by using localized Joule heating of microheaters and laminar flow of multiple precursor solutions with minimal inter-diffusion within the microfluidic platform. This method can provide not only the accurate control of synthesis locations but also the selection of synthesized nanomaterials. By using this technology, heterogeneous nanomaterials can be integrated in microscale region without complicated alignment procedures, which is expected to be very useful for ultra-compact, low-power mobile sensors. The gas sensors fabricated by this approach exhibited good gas sensing performances for sub-ppm NO2 and tens of ppm CO gas detection, proving a strong potential towards multiplexed gas sensing platform. Furthermore, this approach is expected to be very useful for the fabrication of numerous functional nanodevices that require highly integrated array of heterogeneous nanomaterials such as chemical sensors, bio sensors, field emission devices and photodetectors.

Methods

Fabrication process of the sensor chip and microfluidic platform

(a) Sensor chip

Photoresist (PR; AZ5214, MicroChemicals GmbH, Germany) was patterned by using photolithography process on the Si wafer with 2 μm thick thermal oxide to fabricate serpentine microheater layer. A 200 nm thick platinum (Pt) film was deposited on the substrate by e-beam evaporation. The substrate was immersed in the acetone with sonication for removing the PR pattern and dummy Pt layer. Afterwards, a 600 nm thick silicon dioxide (SiO2) layer was deposited on the substrate by plasma enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD; Concept Two Sequel/Speed, Novellus Systems, Inc., USA) with deposition rate of 43 nm/min for electrical insulation. That was deposited at 250°C with 30 W of plasma power under 900 mTorr of SiH4, N2O and N2 gas mixture. PR was patterned again on the SiO2 layer for interdigitated electrodes by aligning with the underlying microheaters. A 200 nm thick gold (Au) film was deposited on the substrate by e-beam evaporation for electrodes. The PR pattern and dummy Au layer were removed in the acetone.

(b) Microfluidic platform

A 100 μm thick SU-8 (SU-8 100, MicroChemicals GmbH, Germany) structure was patterned on the Si wafer by using photolithography process. The PDMS (SYLGARD® 184, Dow Corning, USA) microchannels were fabricated by conventional PDMS replication method on the SU-8 master template. The mixture with a 10:1 weight ratio of liquid PDMS prepolymer to curing agent was poured onto the master template. The PDMS was cured at 80°C for 3 hours in a convection oven and peeled off from the master template.

Preparation of the precursor solutions

Four kinds of precursor solutions were prepared for this paper as follows. The ZnO nanowire precursor solution consisted of 4 mM zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO3)2·6H2O), 4 mM hexamethylenetetramine (HMTA, C6H12N4) and 1 mM polyethyleneimine (PEI) in DI water31. Two kinds of CuO nanospike precursor solution were prepared; a solution consisting of 4 mM copper(II) nitrate hydrate (Cu(NO3)2·xH2O) and 4 mM HMTA in DI water for CuO nanospike in step 1 and diluted solution consisting of 1 mM copper(II) nitrate hydrate and 1 mM HMTA in DI water for slow reaction for ZnO nanowire/CuO nanospike hybrid nanostructure in step 2(II)32. The TiO2 precursor solution consisted of 0.3 M boric acid (H3BO3) and 0.1 M ammonium hexafluorotitanate ((NH4)2TiF6) in DI water33. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Synthesis of the nanomaterials in the microfluidic platform

The sensor chip and microfluidic platform were bonded by a jig instead of plasma assisted adhesion or stamp-and-stick binding methods for easy and clean detachment. Polyether ether ketone (PEEK) tubes (PEEK™ Tubing, Upchurch Scientific, USA) with 360 μm outer diameter and 150 μm inner diameter were connected between inlets of microfluidic platform and syringe pumps. The syringes contained precursor solutions or DI water and flow of the solutions was controlled by automated syringe pumps. A thicker tube (775 μm outer diameter and 508 μm inner diameter) was connected to outlet of microfluidic platform for discharge of used precursor solutions. The microheaters on the sensor chip were connected in parallel to power supply for Joule heating. (See Figure S1 for the schematic and real picture of synthesis setup).

(a) Single nanomaterial synthesis

In order to synthesize ZnO nanowires on the electrode #1, the ZnO precursor was supplied to inlet #1 and DI water was supplied to inlet #2 and #3 with an identical flow speed of 5 mm/s flow. At the same time, the 3.8 V DC bias was applied across microheater #1 for 4 minutes; In order to synthesize ZnO nanowires on the electrode #2, the ZnO precursor was supplied to inlet #2 and DI water was supplied to inlet #1 and #3 with an identical flow speed of 5 mm/s. At the same time, the 3.8 V DC bias was applied across microheater #2 for 4 minutes.

(b) Heterogeneous nanomaterial array synthesis

In step 1, the ZnO precursor solution was supplied to the inlet #1 and #3 and CuO precursor solution was supplied to the inlet #2 with an identical flow speed of 5 mm/s while applying 3.8 V of electrical bias to all of three microheaters for 4 minutes. In step 2(I), the TiO2 precursor solution was supplied to the inlet #1 and DI water was supplied to the other inlets with an identical flow speed of 5 mm/s for 5 minutes without applying electrical energy. In step 2(II), the diluted CuO precursor solution was supplied to the inlet #1 and DI water was supplied to the other inlets with an identical flow speed of 5 mm/s while applying 3.8 V electrical bias to microheater #1 for 10 seconds.

(c) ZnO nanomaterial synthesis at various flow speeds

The ZnO precursor solution was supplied to the inlet #1 and DI water was supplied to the inlet #2 and #3 while applying 3.8 V electrical bias only to microheater #1 for 20 minutes. The flow speed of the three inlets were changed from 5 to 20, 100, 500 mm/s.

Numerical simulation of nanomaterial synthesis in the microfluidic platform

(a) Heterogeneous nanomaterial array synthesis

The numerical simulation of nanomaterial synthesis in the microfluidic platform was conducted by using COMSOL Multiphysics® with ‘fluid flow’ and ‘chemical species transport’ models. The microfluidic platform consisted of three rectangular inlet channel with a width of 200 μm and height of 100 μm and these were joined the one main channel with a width of 600 μm and height of 100 μm. The flows were supplied to each inlets with 5 mm/s speed and the outlet was assumed as atmospheric pressure. All boundaries were considered with isothermal condition and the target microheater area was set up the target temperature. In order to simulate of ZnO nanowire - CuO nanospikes - ZnO nanowires array synthesis, 4 mM Zn2+ ion and 16 mM OH− ion were supplied to the inlet #1 and #3 and 4 mM Cu2+ ion and 16 mM OH− ion were supplied to the inlet #2. All three microheater were set up 95°C. For conversion to TiO2 nanotubes from ZnO nanowires, 100 mM Ti+ ion and 600 mM F− ion were supplied to the inlet #1 and all domains are maintained room temperature. For additional CuO nanospikes synthesis on ZnO nanowires, 1 mM Cu2+ ion and 4 mM OH− ion were supplied to the inlet #1. The microheater #1 was set up 95°C and the other microheaters area considered as isothermal condition.

(b) ZnO nanomaterial synthesis at various flow speeds

The geometry and boundary conditions were the same as above heterogeneous nanomaterial array synthesis conditions except flow rate and ion concentration. 1 mM Zn2+ ion and 4 mM OH− ion were supplied to the inlet #1 and the microheater #1 was set up 95°C. The flow speed of the three inlets were adjusted to 1, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 500, 1000 mm/s.

(c) ZnO nanomaterial synthesis for different ratio of flow speeds

The geometry, boundary conditions and concentration of precursor solution were the same as above condition (b: ZnO nanomaterial synthesis at various flow speeds) except flow speed and heat source. The flow speed of inlet #1, #2 and #3 were changed from (5, 5 and 5 mm/s) to (3.75, 5.625 and 5.625 mm/s), (3, 6 and 6 mm/s) and (2.143, 6.429 and 6.429 mm/s) for flow speed ratio of 1:1:1 to 1:1.5:1.5, 1:2:2 and 1:3:3 in inlet #1, #2 and #3 with constant average flow speed of 5 mm/s. A constant heating power of 0.85 W was supplied to the microheater #1 for all of the flow ratios.

References

Eranna, G., Joshi, B. C., Runthala, D. P. & Gupta, R. P. Oxide materials for development of integrated gas sensors - A comprehensive review. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 29, 111–188 (2004).

Williams, D. E. Semiconducting oxides as gas-sensitive resistors. Sensor. Actuat. B-Chem. 121, 18–35 (2007).

Kim, S. J., Hwang, I. S., Kang, Y. C. & Lee, J. H. Design of selective gas sensors using additive-loaded In2O3 hollow spheres prepared by combinatorial hydrothermal reactions. Sensors (Basel) 11, 10603–10614 (2011).

Liu, A. Towards development of chemosensors and biosensors with metal-oxide-based nanowires or nanotubes. Biosens. Bioelectron. 24, 167–177 (2008).

Lee, J.-H. Gas sensors using hierarchical and hollow oxide nanostructures: Overview. Sensor. Actuat. B-Chem. 140, 319–336 (2009).

Comini, E., Faglia, G., Sberveglieri, G., Pan, Z. & Wang, Z. L. Stable and highly sensitive gas sensors based on semiconducting oxide nanobelts. Appl. Phys. Lett. 81, 1869–1871 (2002).

Van Hieu, N. et al. Comparative study on CO2 and CO sensing performance of LaOCl-coated ZnO nanowires. J. Hazard. Mater. 244–245, 209–216 (2013).

Yanbai, S. et al. Synthesis of SnO2 nanorods and application to H2 sensor. J. Alloys Compd. 593, 271–274 (2014).

Ramgir, N. S. et al. Room temperature H2S sensor based on Au modified ZnO nanowires. Sensor. Actuat. B-Chem. 186, 718–726 (2013).

Chinh, N. D. et al. Comparative NO2 gas-sensing performance of the self-heated individual, multiple and networked SnO2 nanowire sensors fabricated by a simple process. Sensor. Actuat. B-Chem. 201, 7–12 (2014).

Da Silva, L. F. et al. A novel ozone gas sensor based on one-dimensional (1D) α-Ag2WO4 nanostructures. Nanoscale 6, 4058–4062 (2014).

Kim, N.-H. et al. Highly sensitive and selective hydrogen sulfide and toluene sensors using Pd functionalized WO3 nanofibers for potential diagnosis of halitosis and lung cancer. Sensor. Actuat. B-Chem. 193, 574–581 (2014).

Steinhauer, S., Brunet, E., Maier, T., Mutinati, G. C. & Köck, A. Suspended CuO nanowires for ppb level H2S sensing in dry and humid atmosphere. Sensor. Actuat. B-Chem. 186, 550–556 (2013).

Van Hieu, N., Van Vuong, H., Van Duy, N. & Hoa, N. D. A morphological control of tungsten oxide nanowires by thermal evaporation method for sub-ppm NO2 gas sensor application. Sensor. Actuat. B-Chem. 171–172, 760–768 (2012).

Hwang, I.-S. et al. Large-scale fabrication of highly sensitive SnO2 nanowire network gas sensors by single step vapor phase growth. Sensor. Actuat. B-Chem. 165, 97–103 (2012).

Leiterer, C. et al. Applying contact to individual silicon nanowires using a dielectrophoresis (DEP)-based technique. J. Nanopart. Res. 15, 1628 (2013).

Yan, Z. et al. Three-dimensional optical trapping and manipulation of single silver nanowires. Nano Lett. 12, 5155–5161 (2012).

Reynolds, K. et al. Probe based manipulation and assembly of nanowires into organized mesostructures. Nanotechnology 19, 485301 (2008).

Liu, M., Peng, Y., Guo, Q. Q., Luo, J. & Yang, J. Large-scale patterning and assembly of carbon nanotubes by microfluidic hydrodynamic focusing. Adv. Mat. Res. 194–196, 503–506 (2011).

Yu, G. et al. Contact printing of horizontally-aligned p-type Zn3P2 nanowire arrays for rigid and flexible photodetectors. Nanotechnology 24, 095703 (2013).

Lodish, H. et al. Molecular cell biology Ch. 1 (Freeman, W. H. New York, 2007).

Zhang, K., Yang, Y., Pun, E. Y. B. & Shen, R. Local and CMOS-compatible synthesis of CuO nanowires on a suspended microheater on a silicon substrate. Nanotechnology 21, 235602 (2010).

Persaud, K. & Dodd, G. Analysis of discrimination mechanisms in the mammalian olfactory system using a model nose. Nature 299, 352–355 (1982).

Chávez, F. et al. Sensing performance of palladium-functionalized WO3 nanowires by a drop-casting method. Appl. Surf. Sci. 275, 28–35 (2013).

Choudhary, M., Singh, N. K., Mishra, V. N. & Dwivedi, R. Selective detection of hydrogen sulfide using copper oxide-doped tin oxide based thick film sensor array. Mater. Chem. Phys. 142, 370–380 (2013).

Kukkola, J. et al. Inkjet-printed gas sensors: Metal decorated WO3 nanoparticles and their gas sensing properties. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 17878–17886 (2012).

Sato, H., Yui, M. & Yoshikawa, H. J. Ionic diffusion coefficients of Cs+, Pb2+, Sm3+, Ni2+, SeO2−4 and TcO−4 in free water determined from conductivity measurements. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 33, 950–955 (1996).

Robinson, R. A. & Stokes, R. H. Electrolyte Solutions (Dover Publications, New York, 2002).

Dane, J. H., Topp, G. C. & Campbell, G. S. Methods of soil analysis: Physical methods (Soil Science Society of America, Madison, 2002).

Buffle, J., Zhang, Z. & Startchev, K. Metal flux and dynamic speciation at (Bio)interfaces. Part I: Critical evaluation and compilation of physicochemical parameters for complexes with simple ligands and fulvic/humic substances. Environ. Sci. Technol. 41, 7609–7620 (2007).

Law, M., Greene, L. E., Johnson, J. C., Saykally, R. & Yang, P. Nanowire dye-sensitized solar cells. Nat. Mater. 4, 455–459 (2005).

Li, D. et al. CuO nanostructures prepared by a chemical method. J. Cryst. Growth 282, 105–111 (2005).

Deki, S., Aoi, Y., Hiroi, O. & Kajinami, A. Titanium (IV) oxide thin films prepared from aqueous solution. Chem. Lett. 25, 433–434 (1996).

Stroock, A. D. et al. Chaotic mixer for microchannels. Science 295, 647–651 (2002).

Ou, J., Moss, G. R. & Rothstein, J. P. Enhanced mixing in laminar flows using ultrahydrophobic surfaces. Phys. Rev. E 76, 016304 (2007).

Bui, C. T. et al. Diameter-dependent thermal transport in individual ZnO nanowires and its correlation with surface coating and defects. Small 8, 738–745 (2012).

Young, H. D. University physics (Addison-Wesley, Boston, 1992).

Chiu, S. W. & Tang, K. T. Towards a chemiresistive sensor-integrated electronic nose: A review. Sensor (Basel) 13, 14214–14247 (2013).

Dubois, M. et al. A carbonaceous chemical filter for the selective detection of NO2 in the environment. Carbon, 52, 17–29 (2013).

Sysoev, V. V., Button, B. K., Wepsiec, K., Dmitriev, S. & Kolmakov, A. Toward the nanoscopic “electronic nose”: Hydrogen vs carbon monoxide discrimination with an array of individual metal oxide nano- and mesowire sensors. Nano Lett. 6, 1584–1588 (2006).

Oh, E. et al. High-performance NO2 gas sensor based on ZnO nanorod grown by ultrasonic irradiation. Sensor. Actuat. B-Chem. 141, 239–243 (2009).

Zhuo, Y., Huang, L., Ling, Y., Li, H. & Wang, J. A novel NO2 sensor based on TiO2 nanotubes array with in-situ Au decoration. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 13, 1177–1181 (2013).

Das, A. et al. Facile synthesis of nanostructured CuO for low temperature NO2 sensing. Physica E. 54, 40–44 (2013).

Liu, C.-Y., Chen, C.-F. & Leu, J.-P. Fabrication and CO sensing properties of mesostructured ZnO gas sensors. J. Electrochem. Society 156, J16–J19 (2009).

Park, J.-A. et al. Structure and CO gas sensing properties of electrospun TiO2 nanofibers. Mater. Lett. 64, 255–257 (2010).

Aslani, A. & Oroojpour, V. CO gas sensing of CuO nanostructures, synthesized by an assisted solvothermal wet chemical route. Physica B 406, pp. 144–149 (2011).

Moon, W. J., Yu, J. H. & Choi, G. M. The CO and H2 gas selectivity of CuO-doped SnO2-ZnO composite gas sensor. Sensor. Actuat. B-Chem. 87, 464–470 (2009).

World Health Organization, WHO Air quality guidelines for particulate matter, ozone, nitrogen dioxide and sulfur dioxide (World Health Organization, Geneva, 2006).

World Health Organization, Guidelines for Air Quality(World Health Organization, Geneva, 2000).

Le, D. T. T. et al. Density-controllable growth of SnO2 nanowire junction-bridging across electrode for low-temperature NO2 gas detection. J. Mater. Sci. 48, 7253–7259 (2013).

An, S. et al. Enhanced gas sensing properties of branched ZnO nanowires. Thin Solid Films 547, 241–245 (2013).

Brunet, E. et al. Comparison of the gas sensing performance of SnO2 thin film and SnO2 nanowire sensors. Sensor. Actuat. B-Chem. 165, 110–118 (2012).

Fort, A. et al. Metal-oxide nanowire sensors for CO detection: Characterization and modeling. Sensor. Actuat. B-Chem. 148, 283–291 (2010).

Tomchenko, A. A., Harmer, G. P., Marquis, B. T. & Allen, J. W. Semiconducting metal oxide sensor array for the selective detection of combustion gases. Actuat. B-Chem. 93, 126–134 (2003).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Center for Integrated Smart Sensors funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology as Global Frontier Project (CISS-2012-M3A6A6054201) and Nano Material Technology Development Program (No. 2013043661) and Brain Korea 21 (BK21) Plus Project through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, ICT & Future Planning.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.Y. and I.P. implemented original ideas and detailed mechanisms, with help from K.N.K., D.K. and Z.L. D.Y., K.N.K., D.K. and I.P. designed and planned the experiments. D.Y. K.N.K. and D.K. performed numerical simulations, fabricated samples, carried out experiments, analyzed experimental data and prepared figures. D.Y. and I.P. wrote the manuscript. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, D., Kang, K., Kim, D. et al. Fabrication of heterogeneous nanomaterial array by programmable heating and chemical supply within microfluidic platform towards multiplexed gas sensing application. Sci Rep 5, 8149 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep08149

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep08149

This article is cited by

-

Ultrasensitive ppb-level H2S gas sensor at room temperature based on WO3/rGO hybrids

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2020)

-

Controlled growth of CH3NH3PbI3 nanowires in arrays of open nanofluidic channels

Scientific Reports (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.