Abstract

The fluorination of p-type metal phthalocyanines produces n-type semiconductors, allowing the design of organic electronic circuits that contain inexpensive heterojunctions made from chemically and thermally stable p- and n-type organic semiconductors. For the evaluation of close to intrinsic transport properties, high-quality centimeter-sized single crystals of F16CuPc, F16CoPc and F16ZnPc have been grown. New crystal structures of F16CuPc, F16CoPc and F16ZnPc have been determined. Organic single-crystal field-effect transistors have been fabricated to study the effects of the central metal atom on their charge transport properties. The F16ZnPc has the highest electron mobility (~1.1 cm2 V−1 s−1). Theoretical calculations indicate that the crystal structure and electronic structure of the central metal atom determine the transport properties of fluorinated metal phthalocyanines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

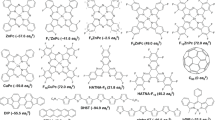

Devices based on organic semiconductors, such as organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs), organic field-effect transistors (OFETs), organic solar cells (OSCs) or emerging printed microelectronic circuits require stable p- and n-type organic semiconductors with excellent electrical and optoelectronic properties. Additionally, it is desired that these organic semiconductors are easily synthesized and stable during the whole life-time. These are thoughtful requirements and all have been achieved but not simultaneously in one organic semiconductor. The highest mobility in organic semiconductors has been achieved in small molecules like the p-type rubrene1. However, rubrene for mass applications is too expensive due to multi-steps synthesis and additionally easily oxidizes2. In contrast, very stable organic semiconductors, like metal phthalocyanines have at least one order of magnitude of lower mobility. To get n-type phthalocyanines, fluorinated phthalocyanines need to be synthesized but the electron mobility in fluorinated phthalocyanines decrease even more. The desirable organic semiconductor with high mobility, low fabrication cost and good air stability is still a big challenge.

A sizeable number of p-type organic semiconductors with mobility larger than 1 cm2 V−1 s−1, have been discovered3,4. However, n-type5,6,7,8 channel candidates have been limited to C60 and its derivatives9, TCNQ and its derivatives10, perylene derivatives11 and halogenated metal phthalocyanines12. Furthermore, only in a few complex molecular structures, the electron mobility is greater than 1 cm2 V−1 s−113,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. For many devices, the mobility of both holes and electrons should be in the same range.

Most high-performance organic semiconductors have complex molecular structures and are synthesized by complicated and expensive processes. Phthalocyanines are the exceptions. They have already been produced in substantial amounts and are used as stable dyes in different branches of industry. However, the charge carrier mobility measured in thin films of metal phthalocyanines is, in general, one or a few orders of magnitude lower than the highest reported value measured for metal phthalocyanine single crystals22. For example, the hole mobility of thin films of copper phthalocyanine (CuPc) is in the range of 10−2 cm2 V−1 s−123, but that of a single crystal can reach even 1 cm2 V−1 s−122. The complementary halogenated copper phthalocyanine has an electron mobility in the range of 10−2 cm2 V−1 s−1 when measured on thin films12,24. Therefore, it is very interesting to explore the intrinsic mobility of metal phthalocyanines to determine whether a stable device with hole and electron mobilities in the range of 1 cm2 V−1 s−1 can be fabricated.

In our studies, copper hexadecafluorophthalocyanine (F16CuPc), cobalt hexadecafluorophthalocyanine (F16CoPc) and zinc hexadecafluorophthalocyanine (F16ZnPc) were selected. For the evaluation of close to intrinsic transport properties, high-quality centimeter-sized single crystals of F16CuPc, F16CoPc and F16ZnPc have been grown. The reported crystal data for F16CuPc from different research groups are different25,26,27,28. Moreover, in the fluorinated metal phthalocyanines, it is not known if the different central metal atoms affect the intermolecular interaction. New crystal structures of F16CuPc, F16CoPc and F16ZnPc have been determined. Organic single-crystal field-effect transistors have been fabricated and the effect of the central metal atom on their charge transport properties has been explored. The observed mobilities in fluorinated metal phthalocyanines with different central metal have been explained using theoretical calculation.

Results

Single-crystal growth and structure analysis

The three powders were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Corporation and purified two times by sublimation in high vacuum. Large-sized single crystals of F16CuPc, F16CoPc and F16ZnPc were obtained by physical vapor transport methods29. The crystal growth was carried out under argon gas flow with pressure in the range of ~1 Torr. The optical images of single crystals of F16CuPc, F16CoPc and F16ZnPc are shown in Fig. 1. The three violet single crystals displayed millimeter-sized square columns. The length of some crystals is greater than 1 centimeter.

The single crystal structures of the three similar molecules were determined by single crystal X-ray diffraction. F16CuPc was of the  space group with a = 4.8529(7) Å, b = 10.2721(14) Å, c = 28.391(4) Å, α = 86.614(9) °, β = 87.879(8) °, γ = 81.701(8) °; F16CoPc was of the

space group with a = 4.8529(7) Å, b = 10.2721(14) Å, c = 28.391(4) Å, α = 86.614(9) °, β = 87.879(8) °, γ = 81.701(8) °; F16CoPc was of the  space group with a = 4.7963(7) Å, b = 10.1976(14) Å, c = 28.092(4) Å, α = 86.590(9) °, β = 88.100(8) °, γ = 81.743(8) °; and F16ZnPc was of the

space group with a = 4.7963(7) Å, b = 10.1976(14) Å, c = 28.092(4) Å, α = 86.590(9) °, β = 88.100(8) °, γ = 81.743(8) °; and F16ZnPc was of the  space group with a = 4.8266(7) Å, b = 10.1610(14) Å, c = 27.977(4) Å, α = 86.186(9) °, β = 87.482(8) °, γ = 80.664(8) °. (See the SI, Fig. S1–S3, molecular packing of F16CuPc, F16CoPc and F16ZnPc.) The structures of F16CoPc and F16ZnPc were previously not known.

space group with a = 4.8266(7) Å, b = 10.1610(14) Å, c = 27.977(4) Å, α = 86.186(9) °, β = 87.482(8) °, γ = 80.664(8) °. (See the SI, Fig. S1–S3, molecular packing of F16CuPc, F16CoPc and F16ZnPc.) The structures of F16CoPc and F16ZnPc were previously not known.

Single-crystal growth direction determination

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was used to find the crystal growth direction along the columns (Fig. 2a, 2c, 2e). Selected area electron diffraction (SAED) showed that the preferred crystal growth direction of F16CuPc (Fig. 2a–2b), F16CoPc (Fig. 2c–2d) and F16ZnPc (Fig. 2e–2f) was [100]. In the [100] direction, the metal hexadecafluorophthalocyanines form a stack where the metal atoms are at the shortest distances. The crystal direction of [100] is actually the shortest axis of the metal hexadecafluorophthalocyanines, which is also the densest packing of the molecules (Fig. 1e–g).

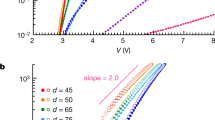

Single-crystal field-effect transistors

The charge transport behavior along the [100] direction of individual crystals of F16CuPc, F16CoPc and F16ZnPc were studied. Micrometer-thin ribbon-like single crystals were used for field-effect transistor measurements. Asymmetrical electrodes (Au and Ag) were used30 and all transistors were fabricated and characterized in air under ambient conditions. All transistors showed n-type characteristics and the mobilities of many devices were larger than 0.1 cm2 V−1 s−1. Typical output and transfer characteristics of F16ZnPc single-crystal FETs are shown in Fig. 3. Some nonlinearity has been found in the output curve of the transistor which may be caused by the contact and access resistances31,32,33. Although the molecular structures of F16CuPc, F16CoPc and F16ZnPc are very similar, the type of central metal atom results in different device mobility. In our experiments, the highest mobility of F16ZnPc single crystals was ~1.1 cm2 V−1 s−1 and that of F16CoPc single crystals was 0.8 cm2 V−1 s−1 (a typical transfer curve from the device is shown in Fig. S4 in the SI), while that of F16CuPc single crystals was 0.6 cm2 V−1 s−133. To our knowledge, these values are higher than those that have been previously reported and may be close to the intrinsic value possible in fluorinated metal phthalocyanines.

Discussion

Some previous reports indicate that the device mobility will increase with decreasing intermolecular spacing distance34. Very dense molecular packing is helpful for charge transport. In metal phthalocyanines, the dimensions of the central metal atoms determine the intermolecular spacing distance35. Lower intermolecular spacing distance will result in higher device mobility35,36. Our experimental results have confirmed this viewpoint. Theoretical calculations were applied to study this structure-property relationship, especially for the function of the metal atoms in metal hexadecafluorophthalocyanines.

The charge transport in organic semiconductors is governed by electronic coupling and electron-phonon interactions, where the latter plays a more profound role in determining charge transport properties. The major transport mechanism can be described by polaron and disorder models37. A simple yet widely applied way to evaluate the electronic coupling between neighboring molecules in organic semiconductors is referred to as the energy level-splitting method38 or “energy splitting in dimer” method. In this work, we have obtained electron transfer integrals by calculating the band structures of F16MePcs crystals along their [100] direction via density functional theory (DFT), where the electrons transfer integrals te between the F16MePcs dimers are taken as 1/4 of the LUMO bandwidth along this direction. We have not displayed the crystal structure for each F16MePc due to their high structural similarity, but a representative structure can be found in Fig. 4(a) and (b). To address the effects of electron-phonon interactions, the polaron binding energy, which is equal to half of the reorganization energy λ, is defined as37

Here,  represents the normal mode displacement along Qj between the equilibrium geometries of neutral and charged (for instance, negatively charged) molecules. The calculated values of polaron binding energies and Huang-Rhys factors are given in Table 1. It has been suggested that the reorganization energy of F16ZnPc is dominated by phonon modes at approximately 1400 cm−139. In a recent DFT work40 on F16MePcs, they have found the phonon modes at approximately 1400 cm−1 for the F16MePcs in this work are almost identical. To determine the largest components of different normal modes towards polaron binding energies, we have calculated both electron-phonon coupling strengths and polaron binding energies for all F16MePcs by adopting the same methods to calculate both quantities37. Detailed results of the electron-phonon coupling calculations can be found in the supporting information. Four groups of vibrational frequencies of the F16MePcs investigated are found to contribute most to the polaron binding energy. Mobility calculations were performed with the aid of a temperature-dependent canonical transformation of the Holstein Hamiltonian by incorporating all physical parameters into the model41,42,43,44,45. The calculated mobilities at room temperature T = 298 K and the measured mobilities are also given in Table 1. It is shown in Table 1 that the calculated mobilities are in good accord with the experiments in terms of trends and orders of magnitude. The overall polaron binding energy and the Huang-Rhys factor indicate that F16CoPc has the strongest electron-phonon coupling strength, although it also has the highest calculated te. Stronger electron-phonon coupling directly contributes to a reduction in its mobility due to an increase in electron-phonon scattering. F16CuPc has slightly smaller S compared to F16CoPc, but it has a much smaller te. Therefore, it is not surprising that F16CuPc has the lowest mobility among these F16MePcs. Owing to its relatively smaller S and its higher electron transfer integral, F16ZnPc is the best compound in terms of mobility. The electronic band structures of these F16MePcs, shown in Fig. 4(c), suggest that all LUMO bands maintain simple 1D feature. From this perspective, we may suspect that the electron transport in these F16MePcs is of 1D character due to close packing of the F16MePc molecules along the [100] direction, as shown in Fig. 4(b). The inter-molecular distances in different crystals are measured as: dF16ZnPc = 3.1942 Å, dF16CoPc = 3.2304 Å and dF16CuPc = 3.2486 Å (Fig. 1e–g), where Co and Cu complexes with non-zero magnetic moments have comparable intermolecular distances that are larger than that of the Zn complex. Interestingly, we can also observe a trend of increasing mobility with decreasing inter-molecular distances in F16MePcs, as indicated in Table 1. Similar behavior was also observed in metallo-porphyrins (E-OEP)35. Unlike those found in E-OEPs, F16MePc with Zn as the center ion has smallest inter-molecular distance. It is worth noting that electron transfer integrals are found to be correlated to either center-metal ion distances or the a-axis length, as also shown in Table 1, although the opposite situation was claimed for E-OEPs35. Further comparison of the inter-molecular distances suggests that F16CoPc should have less π-π overlap compared to F16ZnPc due to larger inter-molecular distances. DFT population analyses of all F16CoPc and F16CuPc complexes (See Table S1 in SI for details) reveal interesting roles for d-orbitals in Co and Cu complexes. In F16CoPc, a super-exchange mechanism may be responsible for its higher electron transfer integral in addition to conventional contributions from intermolecular π-π overlap46. Meanwhile, F16CuPc has a much smaller electron transfer integral due to the lack of a super-exchange mechanism and weaker π-π interactions.

represents the normal mode displacement along Qj between the equilibrium geometries of neutral and charged (for instance, negatively charged) molecules. The calculated values of polaron binding energies and Huang-Rhys factors are given in Table 1. It has been suggested that the reorganization energy of F16ZnPc is dominated by phonon modes at approximately 1400 cm−139. In a recent DFT work40 on F16MePcs, they have found the phonon modes at approximately 1400 cm−1 for the F16MePcs in this work are almost identical. To determine the largest components of different normal modes towards polaron binding energies, we have calculated both electron-phonon coupling strengths and polaron binding energies for all F16MePcs by adopting the same methods to calculate both quantities37. Detailed results of the electron-phonon coupling calculations can be found in the supporting information. Four groups of vibrational frequencies of the F16MePcs investigated are found to contribute most to the polaron binding energy. Mobility calculations were performed with the aid of a temperature-dependent canonical transformation of the Holstein Hamiltonian by incorporating all physical parameters into the model41,42,43,44,45. The calculated mobilities at room temperature T = 298 K and the measured mobilities are also given in Table 1. It is shown in Table 1 that the calculated mobilities are in good accord with the experiments in terms of trends and orders of magnitude. The overall polaron binding energy and the Huang-Rhys factor indicate that F16CoPc has the strongest electron-phonon coupling strength, although it also has the highest calculated te. Stronger electron-phonon coupling directly contributes to a reduction in its mobility due to an increase in electron-phonon scattering. F16CuPc has slightly smaller S compared to F16CoPc, but it has a much smaller te. Therefore, it is not surprising that F16CuPc has the lowest mobility among these F16MePcs. Owing to its relatively smaller S and its higher electron transfer integral, F16ZnPc is the best compound in terms of mobility. The electronic band structures of these F16MePcs, shown in Fig. 4(c), suggest that all LUMO bands maintain simple 1D feature. From this perspective, we may suspect that the electron transport in these F16MePcs is of 1D character due to close packing of the F16MePc molecules along the [100] direction, as shown in Fig. 4(b). The inter-molecular distances in different crystals are measured as: dF16ZnPc = 3.1942 Å, dF16CoPc = 3.2304 Å and dF16CuPc = 3.2486 Å (Fig. 1e–g), where Co and Cu complexes with non-zero magnetic moments have comparable intermolecular distances that are larger than that of the Zn complex. Interestingly, we can also observe a trend of increasing mobility with decreasing inter-molecular distances in F16MePcs, as indicated in Table 1. Similar behavior was also observed in metallo-porphyrins (E-OEP)35. Unlike those found in E-OEPs, F16MePc with Zn as the center ion has smallest inter-molecular distance. It is worth noting that electron transfer integrals are found to be correlated to either center-metal ion distances or the a-axis length, as also shown in Table 1, although the opposite situation was claimed for E-OEPs35. Further comparison of the inter-molecular distances suggests that F16CoPc should have less π-π overlap compared to F16ZnPc due to larger inter-molecular distances. DFT population analyses of all F16CoPc and F16CuPc complexes (See Table S1 in SI for details) reveal interesting roles for d-orbitals in Co and Cu complexes. In F16CoPc, a super-exchange mechanism may be responsible for its higher electron transfer integral in addition to conventional contributions from intermolecular π-π overlap46. Meanwhile, F16CuPc has a much smaller electron transfer integral due to the lack of a super-exchange mechanism and weaker π-π interactions.

Conclusions

In conclusion, high-quality, large-size organic single crystals of F16CuPc, F16CoPc and F16ZnPc were obtained by physical vapor transport. Single crystal structures were determined. Organic single-crystal field-effect transistors have been fabricated to study the effects of the central metal atom on their charge transport properties. The results show that F16ZnPc has the highest electron mobility (~1.1 cm2V−1 s−1). Theoretical calculations indicate that the crystal and electronic structures of the central metal atom determine the transport properties of fluorinated metal phthalocyanines. Relatively high electron transfer integrals and weaker electron-phonon coupling strength were found in F16ZnPc and the electron mobility of single crystals of this material is higher than that of the other two. The electron mobility of F16CoPc is comparable to that of F16ZnPc due to a much larger electron transfer integral, but stronger electron-phonon coupling hinder the electron mobility in F16CoPc. The relatively lower performance of F16CuPc is not surprising due to both stronger electron-phonon coupling and a small electron transfer integral. DFT analyses of the three molecules with different d-orbital occupation suggest the possible contribution of a singly occupied dz2 orbital to the electron transfer integral via a super-exchange mechanism.

Good air, chemical and thermal stability has also been proven in fluorinated metal phthalocyanines12. Some potential applications of fluorinated metal phthalocyanines include phototransistors47, inverters48, memory49, ring oscillators50 and complementary circuits51,52,53. The present results indicate that chemically and thermally stable n- and p-type metal phthalocyanines with mobility in the range of 1 cm2 V−1 s−1 exist and should be considered for use in the mass production of thin film based efficient and low-cost devices.

Methods

Single-crystal growth

A physical vapor transport system with argon flow was used for the purification of source materials and crystal growth. A rotary vacuum pump was used to control the pressure in the quartz tube in the range of ~1 torr. The high-temperature and low-temperature zones were kept at 360°C and 280°C, respectively. All experimental parameters for gas flow and temperature gradient were the same for the above-mentioned three types of crystals. Needle-like crystals that were a centimeter in length were collected for structure determination. If fresh, purified fluorinated metal phthalocyanines were used as the source materials, the single crystals of F16CuPc, F16CoPc and F16ZnPc were repeatedly obtained.

XRD characterization

The X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) data were obtained with a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer. Single crystal structures were collected using a Bruker SMART APEX Π single crystal diffractometer (X-ray radiation, Mo Kα, λ = 0.71073 Å).

Fabrication of organic single-crystal field-effect transistors

Organic single-crystal field-effect transistors (OFETs) were fabricated on a 600-nm SiO2 substrate. The substrate was thermally grown on a heavily-doped n-type silicon wafer, which was used as a gate electrode. The substrate was first immersed in a boiled mixed solution (sulfuric acid (98%):hydrogen peroxide = 3:1) for half an hour to clean the surface. It was then cleaned successively with deionized water, hot acetone and isopropyl alcohol (IPA) in an ultrasonic cleaner for approximately 15 min in each solution. The substrate was finally dried under a stream of N2. Octadecyltrichlorosilane (OTS) modification was carried out for approximately 2 h by the vapor-deposition method. Then, the substrate was rinsed with n-hexane, chloroform and IPA in an ultrasonic cleaner. Finally, the substrate was dried in N2 ambient before use.

For preparation of the FET devices, octadecyltrichlorosilane- (OTS-) modified SiO2/Si substrate was put into the lower-temperature zone of the furnace. Nano-ribbon single crystals of F16CuPc, F16CoPc and F16ZnPc were grown directly on this substrate for ~1–2 h. OFETs based on the individual ribbon-like crystals were fabricated with asymmetrical electrodes (Au and Ag). A thin-bar copper grid (model: M200-CR) was used as the mask. Before the second metal (Ag) was thermally evaporated, the substrate was rotated by 45 degrees. The device fabrication process was the same for all of the three types of single crystals.

I-V characteristics of F16CuPc, F16CoPc and F16ZnPc single-crystal FETs were measured using a Keithley 4200-SCS and a micromanipulator probe station in a shielded box at room temperature in air.

Density functional theory calculations

The unit cells of F16MePcs were relaxed at the level of density functional theory (DFT) using the Quantum-Espresso (QE) package54. The PBE functional with Grimme's dispersion corrections (G06) and the ultra-soft pseudopotential were used throughout all calculations. Spin polarization was considered in performing the geometry optimization and band structure calculations. A plane-wave cutoff of 50 Ry and a Monkhorst-Pack k-point grid of 3 × 1 × 1 were adopted throughout the optimization. A finite Methfessel-Paxton type of smearing with spreading of 0.01 Ry was applied. Convergence of optimization was reached when the total energy and force convergence were lower than 1 × 10−5 Ry and 1 × 10−3 a.u., respectively. For the self-consistent field (SCF) of the calculations, the convergence criteria were all set to 1 × 10−7 Ry. In performing geometry optimizations for the F16MePc unit cells, we constrained the lattice parameters to experimental values, allowing only relaxation of atom positions. Furthermore, geometry optimization, vibrational frequencies, polaron binding energies, population analysis and molecular orbital analysis were carried out at the level of B3LYP density functional and with hybrid basis sets of 6–31G** for non-metallic elements and SDD effective core potential (ECP) for transition metal atoms using the ORCA 3.0.0 package55 for single F16MePc molecules. Single point energy calculations of F16MePC dimers were also performed using same methods. In the ORCA geometry optimization runs, convergence tolerances were set to smaller than 5 × 10−6 Ha for energy change, max gradient smaller than 3 × 10−4 Ha/bohr, root mean square gradient smaller than 1 × 10−4 Ha/bohr, max displacement smaller than 4 × 10−3 bohr and root mean square displacement smaller than 2 × 10−3 bohr. For both ORCA geometry optimization and single point calculations, the convergence criteria were all set to 1 × 10−8 Ha.

Mobility calculations

Mobility for the organic crystals along any transfer path was determined by the diffusion coefficient of polarons formed by electrons and phonons through the Einstein relationship as follows: μ = eβD, where e is the charge of an electron, β = 1/kBT and kB is the Boltzmann constant. Only local electron-phonon coupling was considered, as both Huang-Rhys factors and transfer integrals suggest that the polarons should be well localized on single lattice sites41. Mobility contributions from both band-like and hopping transport were simultaneously considered in this model. Other model parameters include a finite phonon bandwidth of Δω = 0.1 ω0. A constant scattering rate of Γ0 = 1 × 10−4 ω0 was also considered to account for the effects of impurities on band-like mobilities.

References

Takeya, J. et al. Very high-mobility organic single-crystal transistors with in-crystal conduction channels. Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 102120 (2007).

Kloc, C., Tan, K., Toh, M., Zhang, K. & Xu, Y. Purity of rubrene single crystals. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 95, 219–224 (2009).

Sokolov, A. N. et al. From computational discovery to experimental characterization of a high hole mobility organic crystal. Nat. Commun. 2, 437 (2011).

Yuan, Y. et al. Ultra-high mobility transparent organic thin film transistors grown by an off-centre spin-coating method. Nat. Commun. 5, 3005 (2014).

Usta, H., Facchetti, A. & Marks, T. J. n-Channel Semiconductor Materials Design for Organic Complementary Circuits. Acc. Chem. Res. 44, 501–510 (2011).

Jung, B. J., Tremblay, N. J., Yeh, M.-L. & Katz, H. E. Molecular Design and Synthetic Approaches to Electron-Transporting Organic Transistor Semiconductors. Chem. Mater. 23, 568–582 (2011).

Anthony, J. E., Facchetti, A., Heeney, M., Marder, S. R. & Zhan, X. n-Type Organic Semiconductors in Organic Electronics. Adv. Mater. 22, 3876–3892 (2010).

Wen, Y. & Liu, Y. Recent Progress in n-Channel Organic Thin-Film Transistors. Adv. Mater. 22, 1331–1345 (2010).

Guldi, D. M., Illescas, B. M., Atienza, C. M., Wielopolski, M. & Martín, N. Fullerene for Organic Electronics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1587–1597 (2009).

Menard, E. et al. High-Performance n- and p-type Single-Crystal Organic Transistors with Free-Space Gate Dielectrics. Adv. Mater. 16, 2097–2101 (2004).

Jones, B. A., Facchetti, A., Wasielewski, M. R. & Marks, T. J. Tuning Orbital Energetics in Arylene Diimide Semiconductors. Materials Design for Ambient Stability of n-Type Charge Transport. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 15259–15278 (2007).

Bao, Z., Lovinger, A. J. & Brown, J. New Air-Stable n-Channel Organic Thin Film Transistors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 207–208 (1998).

Li, H. et al. High-Mobility Field-Effect Transistors from Large-Area Solution-Grown Aligned C60 Single Crystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 2760–2765 (2012).

Ando, S. et al. n-Type Organic Field-Effect Transistors with Very High Electron Mobility Based on Thiazole Oligomers with Trifluoromethylphenyl Groups. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 14996–14997 (2005).

Ahmed, E., Briseno, A. L., Xia, Y. & Jenekhe, S. A. High Mobility Single-Crystal Field-Effect Transistors from Bisindoloquinoline Semiconductors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 1118–1119 (2008).

Shukla, D. et al. Thin-Film Morphology Control in Naphthalene-Diimide-Based Semiconductors: High Mobility n-Type Semiconductor for Organic Thin-Film Transistors. Chem. Mater. 20, 7486–7491 (2008).

Molinari, A. S., Alves, H., Chen, Z., Facchetti, A. & Morpurgo, A. F. High Electron Mobility in Vacuum and Ambient for PDIF-CN2 Single-Crystal Transistors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 2462–2463 (2009).

Che, C. M. et al. Single microcrystals of organoplatinum(II) complexes with high charge-carrier mobility. Chem. Sci. 2, 216–220 (2011).

Zhang, F. et al. Critical Role of Alkyl Chain Branching of Organic Semiconductors in Enabling Solution-Processed N-Channel Organic Thin-Film Transistors with Mobility of up to 3.50 cm2 V–1 s–1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 2338–2349 (2013).

Yun, S. W. et al. High-Performance n-type Organic Semiconductors: Incorporating Specific Electron-Withdrawing Motifs to Achieve Tight Molecular Stacking and Optimized Energy Levels. Adv. Mater. 24, 911–915 (2012).

Lezama, I. G. et al. Single-crystal organic charge-transfer interfaces probed using Schottky-gated heterostructures. Nat. Mater. 11, 788–794 (2012).

Zeis, R., Siegrist, T. & Kloc, Ch. Single-crystal field-effect transistors based on copper phthalocyanine. Appl. Phys. Lett. 86, 022103 (2005).

Bao, Z., Lovinger, A. J. & Dodabalapur, A. Organic field-effect transistors with high mobility based on copper phthalocyanine. Appl. Phys. Lett. 69, 3066–3068 (1996).

Ling, M.-M., Bao, Z. & Erk, P. Air-stable n-channel copper hexachlorophthalocyanine for field-effect transistors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 163516 (2006).

Yoon, S. M., Song, H. J., Hwang, I.-C., Kim, K. S. & Choi, H. C. Single crystal structure of copper hexadecafluorophthalocyanine (F16CuPc) ribbon. Chem. Commun. 46, 231–233 (2009).

Tang, Q., Li, H., Liu, Y. & Hu, W. High-performance air-stable n-type transistors with an asymmetrical device configuration based on organic single-crystalline submicrometer/nanometer ribbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 14634–14639 (2006).

Pandey, P. A. et al. Resolving the Nanoscale Morphology and Crystallographic Structure of Molecular Thin Films: F16CuPc on Graphene Oxide. Chem. Mater. 24, 1365–1370 (2012).

de Oteyza, D. G., Barrena, E., Ossó, J. O., Sellner, S. & Dosch, H. Thickness-dependent structural transitions in fluorinated copper-phthalocyanine (F16CuPc) films. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 15052–15053 (2006).

Jiang, H. & Kloc, C. Single-crystal growth of organic semiconductors. MRS Bull. 38, 28–33 (2013).

Jiang, H. et al. High-Performance Organic Single-Crystal Field-Effect Transistors of Indolo[3,2-b]carbazole and Their Potential Applications in Gas Controlled Organic Memory Devices. Adv. Mater. 23, 5075–5080 (2011).

Bao, Z. & Locklin, J. Organic Field-Effect Transistors. (CRC, Boca Raton, 2007).

Zimmerling, T. & Batlogg, B. Improving charge injection in high-mobility rubrene crystals: From contact-limited to channel-dominated transistors. J. Appl. Phys. 115, 164511 (2014).

Jiang, H., Tan, K. J., Zhang, K. K., Chen, X. & Kloc, C. Ultrathin organic single crystals: fabrication, field-effect transistors and thickness dependence of charge carrier mobility. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 4771–4773 (2011).

Dong, H., Wang, C. & Hu, W. High performance organic semiconductors for field-effect transistors. Chem. Commun. 46, 5211–5222 (2010).

Minari, T. et al. Molecular-packing-enhanced charge transport in organic field-effect transistors based on semiconducting porphyrin crystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 123501 (2007).

Li, L. et al. An ultra closely pi-stacked organic semiconductor for high performance field-effect transistors. Adv. Mater. 19, 2613–2617 (2007).

Coropceanu, V. et al. Charge Transport in Organic Semiconductors. Chem. Rev. 107, 926–952 (2007).

Hutchison, G. R., Ratner, M. A. & Marks, T. J. Intermolecular charge transfer between heterocyclic oligomers. Effects of heteroatom and molecular packing on hopping transport in organic semiconductors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 16866–16881 (2005).

da Silva Filho, D. A., Coropceanu, V., Gruhn, N. E., de Oliveira Neto, P. H. & Brédas, J.-L. Intramolecular reorganization energy in zinc phthalocyanine and its fluorinated derivatives: a joint experimental and theoretical study. Chem. Commun. 49, 6069–6071 (2013).

Arillo-Flores, O. I., Fadlallah, M. M., Schuster, C., Eckern, U. & Romero, A. H. Magnetic, electronic and vibrational properties of metal and fluorinated metal phthalocyanines. Phys. Rev. B 87, 165115 (2013).

Chen, D., Ye, J., Zhang, H. & Zhao, Y. On the Munn−Silbey Approach to Polaron Transport with Off-Diagonal Coupling and Temperature-Dependent Canonical Transformations. J. Phys. Chem. B 115, 5312–5321 (2011).

Silbey, R. & Munn, R. W. General theory of electronic transport in molecular crystals. I. Local linear electron-phonon coupling. J. Chem. Phys. 72, 2763–2773 (1980).

Munn, R. W. & Silbey, R. Theory of electronic transport in molecular crystals. II. Zeroth order states incorporating nonlocal linear electron-phonon coupling. J. Chem. Phys. 83, 1843–1853 (1985).

Munn, R. W. & Silbey, R. Theory of electronic transport in molecular crystals. III. Diffusion coefficient incorporating nonlocal linear electron-phonon coupling. J. Chem. Phys. 83, 1854–1864 (1985).

Zhao, Y., Brown, D. W. & Lindenberg, K. On the Munn-Silbey approach to nonlocal exciton-phonon coupling. J. Chem. Phys. 100, 2335–2345 (1994).

Anderson, P. W. New Approach to the Theory of Superexchange Interactions. Phys. Rev. 115, 2–13 (1959).

Tang, Q. et al. Photoswitches and phototransistors from organic single-crystalline sub-micro/nanometer ribbons. Adv. Mater. 19, 2624–2628 (2007).

Huang, C., Katz, H. E. & West, J. E. Organic field-effect inversion-mode transistors and single-component complementary inverters on charged electrets. J. Appl. Phys. 100, 114512 (2006).

Wang, L., Su, Z. & Wang, C. Nonvolatile organic write-once-read-many-times memory devices based on hexadecafluoro-copper-phthalocyanine. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 213303 (2012).

Lin, Y.-Y. et al. Organic complementary ring oscillators. Appl. Phys. Lett. 74, 2714–2716 (1999).

Rogers, J. A., Dodabalapur, A., Bao, Z. & Katz, H. E. Low-voltage 0.1 μm organic transistors and complementary inverter circuits fabricated with a low-cost form of near-field photolithography. Appl. Phys. Lett. 75, 1010–1012 (1999).

Klauk, H., Zschieschang, U., Pflaum, J. & Halik, M. Ultralow-power organic complementary circuits. Nature 445, 745–748 (2007).

Crone, B. et al. Large-scale complementary integrated circuits based on organic transistors. Nature 403, 521–523 (2000).

Giannozzi, P. et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 21, 395502 (2009).

Neese, F. The ORCA program system. WIREs Compt. Mol. Sci. 2, 73–78 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This research is conducted by NTU-HUJ-BGU Nanomaterials for Energy and Water Management Programme under the Campus for Research Excellence and Technological Enterprise (CREATE) that is supported by the National Research Foundation, Prime Minister's Office, Singapore. The authors also would like to thank the A*Star Computational Resource Center (A*CRC) for the computing resources support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.J. and C.K. conceived the experiments. H.J. performed the experiments including single-crystal growth, device fabrication, characterization and data analysis. P.H. performed the TEM characterization. J.Y. and T.B. performed the calculations and simulations. J.Y. prepared Fig. 4 and Table 1 and wrote the the part on theoretical calculations and discussions. F.X.W., K.Z.D., N.W. and S.L.F. analyzed the single crystal structures. H.J. and C.K. co-wrote the manuscript. All of the authors reviewed the manuscript, discussed the data and gave profound suggestions.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supporting Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, H., Ye, J., Hu, P. et al. Fluorination of Metal Phthalocyanines: Single-Crystal Growth, Efficient N-Channel Organic Field-Effect Transistors and Structure-Property Relationships. Sci Rep 4, 7573 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07573

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07573

This article is cited by

-

Preparation and characterization of the phthalocyanine–zinc(II) complex-based nanothin films: optical and gas-sensing properties

Applied Nanoscience (2023)

-

Hybrid materials of carbon nanotubes with fluoroalkyl- and alkyl-substituted zinc phthalocyanines

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2020)

-

Temperature and frequency effect on the electrical properties of bulk nickel phthalocyanine octacarboxylic acid (Ni-Pc(COOH)8)

Applied Physics A (2019)

-

Thin films of chlorosubstituted vanadyl phthalocyanine: charge transport properties and optical spectroscopy study of structure

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.