Abstract

The warm-temperate regions of the globe characterized by dry summers and wet winters (Mediterranean climate; MED) are especially vulnerable to climate change. The potential impact on water resources, ecosystems and human livelihood requires a detailed picture of the future changes in this unique climate zone. Here we apply a probabilistic approach to quantitatively address how and why the geographic distribution of MED will change based on the latest-available climate projections for the 21st century. Our analysis provides, for the first time, a robust assessment of significant northward and eastward future expansions of MED over both the Euro-Mediterranean and western North America. Concurrently, we show a significant 21st century replacement of the equatorward MED margins by the arid climate type. Moreover, future winters will become wetter and summers drier in both the old and newly established MED zones. Should these projections be realized, living conditions in some of the most densely populated regions in the world will be seriously jeopardized.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Mediterranean climate (MED) is a midlatitude transitional climate zone characterized by wet winter and dry summer and is considered one of the most desirable climatic zones for human inhabitation1. Because this climate may be especially sensitive to global change, it has been identified as a possible climate-change “hot spot”2,3. The MED climate is found on the western side of most of the world's continents, wedged between warm temperate (mostly poleward), cold-winter snow (eastward and poleward) and arid (equatorward) climates4,5,6 (see Supplementary Material, Figure S1). The passage to wet and dry conditions persisting throughout the year marks the transition to other warm-temperate climates to the north and arid climates to the south, respectively4 (see Table 1). On the other hand, the severe cold winter months characterize the passage to the snow climate4 (see Table 1). The sharp spatial gradient makes MED zones highly vulnerable to climate change (e.g., Ref. 7). Projections from global climate models from phase five of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP58) suggest that the subtropics will become drier9 and the MED rainfall seasonal cycle greater, with a longer winter rainy season10. Still unanswered, however, is how and why the MED geographic distribution will change under anthropogenic global warming. To be useful for decision making, climate predictions/projections need to be probabilistic and the probability information provided needs to be reliable (e.g., Refs. 11,12). The word “reliable” has a specific technical meaning in probability forecasting13, a meaning that can allow potential users to assess whether the information provided by climate projections might have value. Suppose the predicted/projected probability of the event that a particular location is classified as MED climate (event E) is equal to 0.7. For a reliable prediction/projection system, we could assert that E will actually occur on 70% of occasions where E is forecasted with a probability of 0.711. In this work, we perform for the first time a robust assessment of the probability of MED zones to change under the RCP4.5 medium-low greenhouse gases (GHGs) concentration scenario14 (see Method for details). Our approach makes use of the Köppen-Geiger classification method in its latest version as reviewed in Ref. 15, which is applied to each of the 25 CMIP5 models. The Köppen-Geiger classification is an empirical bio-climatic classification and relies on the pioneering and meticulous field work by ecologists and climatologists during 19th century16,17,18 based on the concept that vegetation zonation, being caused by temperature and water availability, is the best expression of climate types. Conversely, climate zone boundaries are closely associated with certain prevalent vegetation species4,18. Therefore, this classification is well suited for identifying and analyzing the impacts of climate change on natural and anthropic ecosystems. Another advantage of the Köppen-Geiger classification is that it can be easily evaluated on a grid-cell level19 and, therefore, can be applied in both relatively high spatial-resolution regional models20,21,22 and low-resolution global climate models5,19,23. Previous works already analyzed the changes and shifts between the main Köppen-Geiger climate classes (equatorial, arid, warm temperate, snow and polar climate) projected by the CMIP35,24 and CMIP525 models, respectively. However, the works mentioned did not analyze the details of specific climate sub-domains such as the changes in the MED climate (according to the classification, MED is a subtype under the warm temperate domain) as we do. After identifying the MED grid points for each of the 25 CMIP5 models for both historical (1979–2005) and projected climatologies, we assessed the probability for each model grid point of being classified as MED climate (PMED) by computing the multi-model ensemble average. We then estimated the regional MED area (AMED) by spatially integrating PMED multiplied by the grid point area. Previous studies computed the projected area change of the main climate classes by applying the Köppen-Geiger classification directly to the multi-model ensemble-mean output. The information from the contributing single-models was only considered to infer an uncertainty for the aggregated area estimates in the form of intra-ensemble standard deviation. Differently, we exploit all the information contained in the CMIP5 multi-model by computing the probability of the climate-type at the grid point level. This allows a robust assessment of the significance of the projected change of MED probability for each grid point by applying a non-parametric Monte Carlo test. Accordingly, all quantitative computations of MED area change that are performed in this study use only the land grid points where the projected change of PMED passed the 5% significance level (see Method for details). This probabilistic approach can provide quantitative information on the projected changes that are required for decisions on economy and society policy issues.

Results

The CMIP5 Multi-Model Ensemble (MME) effectively reproduces the historical (1979–2005) global distribution of MED climate (Supplementary Material, Figure S2a). The probabilistic information provided by the MME is reliable (see Method section for a thorough definition of the reliability attribute); i.e., the MME probability displays a good match with the conditional frequency of observation given the MME-probability outcomes (Supplementary Material, Figure S2b). The reliability attribute of the MME, as measured by eq. 3 (see Method section), scores the very low value of 0.0006, which is remarkably close to the theoretically perfect zero value. In order to retain all the probabilistic information coming from the single-models, we did not apply any bias correction of the models climatology. If we had applied bias correction to the models, Figure S2 (Supplementary Material) would have shown a perfect match between observation and MME, therefore not providing any information about the actual reliability of the CMIP5 multi-model (Figure S2b). With a few exceptions over western North America, Australia and South America (red grid points in Figure S2a), PMED always exceeds 0.5 in correspondence of all the observed MED grid points over land. On the other hand, the CMIP5 MME displays positive PMED in few grid points over southern Arizona, Mexico and between the Black and Caspian Seas, where no MED grid points are observed during the 1979–2005 period (Supplementary Material, Figure S2a).

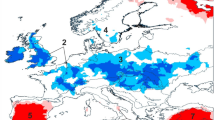

Over both the Euro-Mediterranean (hereinafter Euro-Med) and western North America (hereinafter WNA), PMED increases considerably northward and eastward by the mid-to-end 21st century (Figure 1). By the end of the 21st century, the overall MED area will have expanded in the Euro-Med by as much as 7.4 ± 0.8 · 105 km2 and in WNA by 6.0 ± 1.1 · 105 km2. At the end (mid) of the 21st century, these expansions will correspond to increases of 19 ± 1% (13 ± 1%) and 30 ± 2% (23 ± 2%) over Euro-Med and WNA, respectively. The Southern Hemisphere, on the other hand, is less affected with AMED in South Africa and Australia shrinking somewhat. As shown in Figure 1, although a noticeable effect on PMED is projected over the Southern Hemisphere MED zones, the projected land area changes are one order of magnitude smaller than those in the Northern Hemisphere and are more uncertain. This is at least partly due to the different configuration of the continents in the Southern Hemisphere, which leads to less continental area in the 30°–50° latitude-band, the region where MED zones tend to be located. In fact, South America, with appreciable land between 30°S–50°S latitudes, is the only continent in the Southern Hemisphere with more MED climate areas by the end of the 21st century (Figure 1). In Australia and southern Africa, regions with MED climate are lost because the zone is pushed out of the land into the sea as it moves to higher latitudes, unlike the Northern Hemisphere where the MED zone just expands into the land to the north.

Probability of Mediterranean climate (PMED; see Method for definition) simulated by the CMIP5 models (shaded in red for the period 2070–2100 and in green for 1979–2005).

The contour lines (red for the period 2070–2100 and green for 1979–2005) correspond to 0.5 value. Histogram insets indicate, over each land domain, the change of Mediterranean areal coverage (AMED in units of 105 Km2) with respect to historical (1979–2005) period (MID-21C in blue is for 2035–2065, END-21C in red for 2070–2100). Error bars indicate the uncertainty estimated by the 10th and 90th percentiles of the synthetic distribution obtained by resampling the multi-model members through a Monte Carlo bootstrap (1000 repetitions) procedure. The map in this figure was drawn using Matlab.

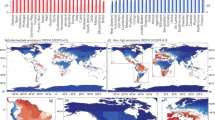

The expansion of MED climate zones in some regions comes at the expense of other climate types and vice versa. Such transitions are shown in Figure 2 for the Euro-Med. The considerable PMED increase projected over northwestern continental Europe, Great Britain, Scandinavia, northern Balkans, Ukraine, Kazakhstan and part of southwestern Russia is displayed in Figure 2a. The corresponding MED area expansion in the latitude band between 38°N and 55°N has the largest area increase at around 49°N (Figure 2b). We verified the robustness of the area changes for each 2-degree latitude band by resampling the multi-model members through a Monte Carlo bootstrap (1000 repetitions) procedure. The 10th and 90th percentiles of the synthetic distribution (shading in Figure 2b) indicate high confidence in the estimated area change at all latitudes. In northwestern Europe, Great Britain and northern Balkans the projected MED zone expands into other warm temperate climates (WarmTemp to MED; crosses in Figure 2a), which will experience a greater winter-summer difference in rainfall in accordance with the typical MED seasonality (Table 1; see Supplementary Material, Figures S3a and S4a). On the other hand, the Ukraine, Kazakhstan, southwestern Russia and Scandinavia areas are projected to shift from snow to MED climate (SNOW to MED; triangles in Figure 2a) owing to a consistent temperature rise during the coldest winter months (Table 1; see Supplementary Material Figure S7). This increase in temperature is coupled with the weakening of the Siberian and Polar highs (negative and positive trends in the Siberian high and Arctic Oscillation indices, respectively; see Supplementary Material, Figure S8), which strengthen moist westerlies from the Atlantic Ocean26 bringing more winter precipitation to the region (see Supplementary Material Figure S8; this topic is further discussed in a paper by Mariotti et al. submitted to Climate Dynamics). The northward MED expansion is accompanied by the replacement of MED areas with the arid climate-type along the southern margins (MED to ARID; Figure 2a) in Spain, Italy, Greece, as well as the Middle East (empty circles in Figure 2a). As shown in Figure 2c, both the precipitation-driven climate conversions of WarmTemp-to-MED (red line) and MED-to-ARID (blue line) tend to stabilize during the second half of the 21st century. In contrast, the temperature-dependent replacement of snow climate by MED (green line) continues in a nearly constant manner until the end of the 21st century. This is consistent with the notion that the rate of shift of climate zones tends to accelerate with the increase in temperature19. It follows that, even if the temperature increase becomes flatter towards the end of the 21st century27, the temperature-dependent climate-zone shift may still continue at a near-constant rate.

Projected change in Mediterranean climate over the Euro-Mediterranean domain.

(a) The shaded areas represent the 2070–2100 vs. 1979–2005 probability change in Mediterranean climate. Only the probability changes that passed a Monte Carlo significance test at the 5% level are shown. For each probability change value, the markers indicate the dominant climate-type transition (relative majority) between warm temperate to Mediterranean (Warm Temp. to MED; crosses), Mediterranean to arid (MED to ARID; circles) and snow to Mediterranean (SNOW to MED; triangles) climate. The markers are bold when the dominant transition occurs in at least 95% of the models that change from one climate type in 1979–2005 to another one in 2070–2100. The dashed line marks the 0.5 contour of PMED during the reference period (1979–2005). (b) Zonally integrated land area change over the longitude domain displayed in panel a (in units of 104 Km2 per degree latitude). Shading indicates the uncertainty for each latitude band estimated by the 10th and 90th percentiles of the synthetic distribution obtained by resampling the multi-model members through a Monte Carlo bootstrap (1000 repetitions) procedure. (c) The 30-years running mean time series of the land area change contributions integrated over the whole Euro-Mediterranean domain displayed in panel a. The map in this figure was drawn using Matlab.

In contrast to the Euro-Med region, where predominantly warm temperate zones are replaced by MED zones, the temperature-driven expansion (SNOW to MED) characterizes western North America (Figure 3). Here, the increase in PMED extends northeastward and replaces the cold-winter regions in Washington State, Idaho, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico and even British Columbia (see also Supplementary Material, Figure S7). The increase in MED area is projected to peak at 41°N (Figure 3b), but expand considerably to latitudes well above 50°N. Similar to the Euro-Med region, the MED southern margins in southern California, southern Arizona and northern Mexico are replaced by arid climate. The WarmTemp-to-MED transition due to the greater summer-winter difference in rainfall is confined to the northern margin along the Pacific coast and to the southeast margin toward the Gulf of Mexico (see also Supplementary Material, Figures S5a and S6a). Analogous to Euro-Med, the SNOW-to-MED transition continues steadily, whereas the WarmTemp-to-MED transition tends to stabilize during the second half of the 21st century (Figure 3c). Interestingly, the WarmTemp-to-MED transition shows interdecadal variability over WNA, indicating the consistent effect of the radiative boundary forcing (Ref. 14, a summary of the prescribed boundary conditions is in the Method section) at this time-scale. Similar to the impact on large-scale rainfall discussed in Ref. 28, the rapid transition from WarmTemp to MED after 2020 and subsequent deceleration in the mid-21st century appear to be related to the scenario mitigation-pathway of aerosol concentrations14.

Same as Figure 2 but for western North America.

The map in this figure was drawn using Matlab.

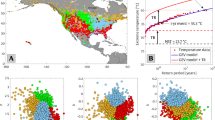

The transition to MED climate in the Euro-Med and WNA regions is characterized by the enhancement of the winter-wet and summer-dry rainfall seasonality (Figure 4; see also Supplementary Material, Figures S3–S6a). The replacement of MED by the arid climate-type along the southern margins is consistently marked by rainfall reduction mostly occurring during winter (Figure 4), partly because these regions are already very dry during summer29. In the MED-to-ARID transition areas along the Mediterranean coast and Middle East, the decrease of wintertime rainfall (see Supplementary Material, Figure S4a) further exacerbates summer dryness (Figure S3a, Supplementary Material) by reducing the water availability for evapotranspiration over land30 (Supplementary Material, Figure S3d). Over the Euro-Med a large summer drying is found in the MED zones already in place and projected to persist during 21st century (i.e., MED to MED) and in the zones transitioning from WarmTemp to MED (Figure 4a). The drier summers are primarily due to the thermodynamic or “direct moisture effect”31, which is particularly important over southeastern Euro-Med (See Supplementary Material, Figure S3). As shown in Figure 4a, the WarmTemp-to-MED transition zone also experiences considerably more rainfall during winter (see also Figure S4) and displays the largest increase in the winter-summer contrast of precipitation over the Euro-Med domain. In contrast to the Euro-Med, the enhanced rainfall seasonality over WNA is dominated by increasingly wetter winters (Figure 4b). In this season, the effect of climate change on the atmospheric dynamics drives a widespread precipitation increase over WNA (Supplementary Material, Figure S6). Consistent with the mechanism described in Ref. 32, the greater subtropical static stability pushes mid-latitude baroclinic instabilities northward, increasing winter precipitation toward the possible MED regions located to the north (Supplementary Material, Figure S6). This mechanism affects the transition between the subtropics and mid-latitudes of both hemispheres. However, due to the limited poleward extension of lands, the winter precipitation in Southern Hemisphere is often shifted out of the continents and towards the southward oceans. This leads to a weaker rainfall seasonal-cycle over land in South Africa and Australia, where the MED zones are projected to shrink (Supplementary Material, Figure S9).

Amplification (2070–2100 minus 1979–2005) of the DJF (blue) vs. JJA (red) precipitation seasonality over zones experiencing a transition from warm temperate to mediterranean (Warm Temp. to MED; denoted by crosses in Figures 2 and 3 with PMED in 2070–2100 > 0.5), Mediterranean to arid (MED to ARID; denoted by circles in Figures 2 and 3 with PMED in 2070–2100 < 0.5) and snow to Mediterranean climate (SNOW to MED; denoted by triangles in Figures 2 and 3 with PMED in 2070–2100 > 0.5). The Mediterranean zones already in place during the historical period (PMED > 0.5 in 1979–2005) and projected to persist during 21st century (PMED > 0.5 in 2070–2100) are also reported (MED to MED). Error bars indicate the uncertainty estimated by the 10th and 90th percentiles of the synthetic distribution obtained by resampling the multi-model members using a Monte Carlo bootstrap (1000 repetitions) procedure.

Discussion

Our probabilistic approach, applied to the future climate projected by the CMIP5 models, shows for the first time that the MED zone will expand markedly during 21st-century. The models project a robust MED expansion, compared to 1979–2005, reaching 7.4 ± 0.8 · 105 Km2 (corresponding to 19 ± 1% increase) over Euro-Mediterranean and 6 ± 1.1 · 105 Km2 (corresponding to 30 ± 2% increase) over western North America by the end of the 21st century. The increased winter-summer rainfall difference drives the MED expansion over warm temperate zones (WarmTemp to MED) in north-western Europe, the United Kingdom and northern Balkans in Euro-Mediterranean and British Columbia and inland southern United States in North America. On the other hand, less severe cold winters, allow the MED to expand northeastward (SNOW to MED) into the continental zones west of the Rocky Mountains and in some parts of Scandinavia, Ukraine and southern Russia. The arid climate type, conversely, will shift poleward into the equatorward MED margins (MED to ARID). The climate changes associated with these transitions would seriously affect natural and anthropic ecosystems. The envisaged transitions from WarmTemp to MED and MED to ARID climates pose serious concerns for the availability of water to support human health and activities. Moreover, the projected MED zones will experience amplified winter and decreased summer precipitation, which could result in greater vulnerability to extreme events: more floods in winter and more droughts, fires and water shortages in summer6,33. When evaluating the future consequences of MED changes on ecosystems and human activities as well as the possible adaptation policies, researchers from a broad spectrum of disciplines and decision makers can make effective use of the unprecedented probabilistic information and robust quantitative assessment provided by this work. The results of this study concern the RCP4.5 medium-low GHGs concentration scenario, quite similar to A1B scenario from CMIP3 widely used in previous research investigations34. Future works will address the sensitivity of the outcomes of this research to the use of aggressive emission scenarios (e.g.: RCP8.5). In order to retain all the probabilistic information coming from the single-models, the results reported in this work are obtained without a bias correction of the models climatology. To further check the robustness of our results, we evaluated the 21st century changes of MED probability and MED Area after application of the bias correction, finding no appreciable effect on the outcomes of this study.

Methods

We use simulations for both present-day climate (historical experiments, 1979–2005) and future climate projection (RCP4.5 experiments, 2006–2100) from 25 Coupled General Circulation Models (CGCMs) available from the World Climate Research Program Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 5 (CMIP58). The historical simulations are prescribed with observed concentrations of atmospheric constituents and other forcings14. The CMIP5 recommendations include GHGs, anthropogenic aerosols, ozone, solar irradiance and land-use change. The projections are forced with a future scenario of the same quantities, which are referred to as the “representative concentration pathway” (RCP8). Among the RCPs that have been considered for CMIP5, we selected the RCP4.5, which depicts a somewhat intermediate GHGs concentration scenario compared with other RCP scenarios14. RCP4.5 is quite similar to the A1B scenario from CMIP3, which has been the most widely used scenario in previous research34. The number in the RCP provides an estimate of the radiative forcing for the year 2100 (relative to preindustrial conditions): in RCP4.5 the radiative forcing increases throughout the 21st century before reaching a level of about  at the end of the century. All available ensemble members from each of the following models is used in this study: GISS-E2-R; IPSL-CM5A-MR; MIROC5; HadGEM2-CC; HadGEM2-ES; bcc-csm1-1; CNRM-CM5; inmcm4; CCSM4; CSIRO-Mk3-6-0; IPSL-CM5B-LR; ACCESS1-0; MRI-CGCM3; HadGEM2-AO; FGOALS-s2; CMCC-CM; IPSL-CM5A-LR; MPI-ESM-LR; MIROC-ESM; MPI-ESM-MR; NorESM1-M; NorESM1-ME; MIROC-ESM-CHEM; CanESM2; and BNU-ESM. After a bilinear interpolation to a common 2.0° × 2.0° spatial grid, the ensemble members provided by each institution are averaged with equal weights to obtain an ensemble mean for each contributing model.

at the end of the century. All available ensemble members from each of the following models is used in this study: GISS-E2-R; IPSL-CM5A-MR; MIROC5; HadGEM2-CC; HadGEM2-ES; bcc-csm1-1; CNRM-CM5; inmcm4; CCSM4; CSIRO-Mk3-6-0; IPSL-CM5B-LR; ACCESS1-0; MRI-CGCM3; HadGEM2-AO; FGOALS-s2; CMCC-CM; IPSL-CM5A-LR; MPI-ESM-LR; MIROC-ESM; MPI-ESM-MR; NorESM1-M; NorESM1-ME; MIROC-ESM-CHEM; CanESM2; and BNU-ESM. After a bilinear interpolation to a common 2.0° × 2.0° spatial grid, the ensemble members provided by each institution are averaged with equal weights to obtain an ensemble mean for each contributing model.

We apply the Köppen-Geiger climate classification, which was originally developed by Ref. 4 and presented in its latest version in 1961 by Refs. 35,36, as reviewed in Ref. 15. It is an empirical bio-climatic classification aimed at defining climatic boundaries in such a way to correspond to those of specific vegetation zones. Five vegetation groups are considered for the classification. In Table 1 the characteristics of the arid (B), warm temperate (C) and snow (D) climate types are summarized. These are the climate groups that are of relevance for this work because they contain or confine with the MED zones. Among the diversity of sub-types of warm temperate climates, the MED climate stands out with its dry summer season, which can be warm or hot and its mild and humid winters4 (Table 1). The future changes of the Köppen-Geiger climate types can be evaluated on a grid cell level, as climatic information for every grid cell becomes available. Therefore, as shown in the previous studies by Refs. 5,23,24 it can be suitably applied to climate model output.

For both the historical period and RCP4.5 projection, the dichotomous [1, 0] event of presence/absence of MED climate is evaluated for each grid point and for each CMIP5 model. The probability of MED occurrence is then assessed by computing the ensemble mean of the (N = 25) CMIP5 models (Eq. 1) for each longitude and latitude (i and j, respectively):

Provided the probabilistic information of the MME is reliable (i.e.: the modeled probability compares the conditional distribution of the observation given the MME result13), the regional MED area coverage can be then estimated by spatially integrating the product of PMED with the total grid-point land area (areai,j):

where Nx and Ny are the total number of longitudes and latitudes, respectively. The correspondence of the MME probability to the conditional averaged observation is characterized by the reliability attribute of the multi-model computed in the space domain for the reference period (1979–2005). Following Ref 13, after discretizing the probability forecasts to a finite set of values (yi; which can take any of the I values y1, y2, yI), the reliability (Rel) is evaluated by the match between the specific values of the MME outcomes (yi) and the conditional probability of observations (actual occurrences of the MED climate, o1) given the MME probability [p(o1|yi)]:

where n is the total number of MME probability-observed event pairs and Ni is the number of times each probability yi occurs in the collection of grid points being verified. Theoretical perfect reliability is achieved when Rel = 0, i.e. there is a perfect match between the issued MME probability and the averaged observation for the specific values of the MME probability. This can be appreciated graphically by drawing the MME probability (x axis) and the conditional distribution of observations (y axis) in a reliability diagram and noticing that the y = x line would correspond to the theoretical perfect reliability (See Supplementary Material, Figure S2b).

The projected changes of the PMED with respect to 1979–2005 are tested for significance by using a Monte Carlo test and only the projected differences that passed the 5% level are considered in the analysis. For each grid point, we tested the null hypothesis of getting as high or higher probability change simply by chance through a Monte Carlo bootstrap method (1000 repetitions). Only the probability changes that passed the Monte Carlo significance test at the 5% level ([ΔPMED(i, j)]sig5%) are used (otherwise set to zero) in the computation of the projected area change (ΔAMED) compared to the reference period (1979–2005):

The robustness of the results in terms of AMED change as well as area-averaged precipitation change is further verified by resampling the multi-model members through a Monte Carlo bootstrap (1000 repetitions) procedure. The 10th and 90th percentiles of the synthetic distribution are then chosen to indicate the confidence in our estimates.

To provide a reference for the comparison of the CMIP5 models for the historical period (1979–2005) over land, we computed the observed MED zones by applying Köppen-Geiger classification to monthly-mean surface air temperature from ERA-Interim reanalysis37 and to monthly-mean precipitation from Climate Prediction Center (CPC) Merged Analysis of Precipitation (CMAP38; Supplementary Material, Figure S1). The latest generation ECMWF reanalysis data available for the satellite era (1979 to the present) is preferred to the station-based global temperature datasets such as HadCRU39 and GISSTEMP40. In fact, the station-based data are conceived to provide climate-change gridded anomalies and do not produce reliable estimates of absolute temperature40, which are required by the Köppen-Geiger climate classification (see Table 1). In particular, the grid-cell temperature anomalies over land are well represented by the measured station data owing to the spatial autocorrelation of anomalies40. In contrast, the observed stations are not necessarily representative for the absolute temperature of the grid cell area due to possible microclimatological and topographical effects. These effects are, on the other hand, well accounted for in the reanalysis data41.

References

Bonada, N. & Resh, V. H. Mediterranean-climate streams and rivers: geographically separated but ecologically comparable freshwater systems. Hydrobiologia 719, 1–29 (2013).

Giorgi, F. Climate change hot-spots. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L08707 (2006).

Diffenbaugh, N. S. & Giorgi, F. Climate change hotspots in the CMIP5 global climate model ensemble. Climatic Change Letters 114, 813–822 (2012).

Köppen, W. Versuch einer Klassifikation der Klimate, vorzugsweise nach ihren Beziehungen zur Pflanzenwelt. Geogr. Zeitschr. 6, 657–679 (1900).

Rubel, F. & Kottek, M. Observed and projected climate shifts 1901–2100 depicted by world maps of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Meteorol. Z. 19, 111–123 (2010).

Lionello, P. The Climate of the Mediterranean Region: From the Past to the Future. [Lionello, P. (ed.)] (Elsevier, London, 2012).

Sternberg, M. et al. [The Use and Misuse of Climatic Gradients for Evaluating Climate Impact on Dryland Ecosystems - an Example for the Solution of Conceptual Problems]. Climate Change - Geophysical Foundations and Ecological Effects. [Blanco, J. & Houshang, K. (eds.)] (InTech, Croatia, 2011).

Taylor, K. E., Stouffer, R. J. & Meehl, G. A. An overview of CMIP5 and the experiment design. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 93, 485–498 (2011).

Liu, C. & Allan, R. P. Observed and simulated precipitation responses in wet and dry regions 1850–2100, Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 034002 (2013).

Lee, J.-Y. & Wang, B. Future change of global monsoon in the CMIP5. Clim Dyn 42, 101–119 (2012).

Corti, S., Weisheimer, A., Palmer, T. N., Doblas-Reyes, F. J. & Magnusson, L. Reliability of decadal predictions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L21712 (2012).

Foresight Reducing the Risks of Future Disasters: Priorities for Decision Makers. Final Project Report, The Government Office of Science, London (2012).

Wilks, D. Statistical Methods in the Atmospheric Sciences Second Edition. (Academic Press, Burlington San Diego and London, 2006).

Meinshausen, M. et al. The RCP Greenhouse Gas Concentrations and their Extension from 1765 to 2300. Clim. Change 109, 213–241 (2011).

Kottek, M., Grieser, J., Beck, C., Rudolf, B. & Rubel, F. World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated. Meteorol. Z. 15, 259–263 (2006).

Colinvaux, P. Ecology. (John Wiley and Sons, New York, 1986).

Shugart, H. H. [Vegetation and climate]. Encyclopedia of Climate and Weather. Volume 2 [Schneider, S. H. (ed.)] [801–804], (Oxford University Press, New York, 1996).

Bonan, G. Ecological Climatology. (Cambridge University Press, New York, 2002).

Mahlstein, I., Daniel, J.-S. & Solomon, S. Pace of shifts in climate regions increases with global temperature. Nature Clim. Change 3, 739–743 (2013).

De Castro, M., Gallardo, C., Jylha, K. & Tuomenvirta, H. The use of a climate-type classification for assessing climate change effects in Europe from an ensemble of nine regional climate models. Clim. Change 81, 329–341 (2007).

Roderfeld, H. et al. Potential impact of climate change on ecosystems of the Barents Sea Region. Clim. Change 87, 283–303 (2008).

Baker, B., Diaz, H., Hargrove, W. & Hoffman, F. Use of the Köppen-Trewartha climate classification to evaluate climatic refugia in statistically derived ecoregions for the People's Republic of China. Clim. Change 98, 113–131 (2010).

Manabe, S. & Holloway, J. L. The Seasonal Variation of the Hydrologic Cycle as Simulated by a Global Model of the Atmosphere. J. Geophys. Res. 80, 1617–1649 (1975).

Hanf, F., Körper, J., Spangehl, T. & Cubasch, U. Shifts of climate zones in multi-model climate change experiments using the Köppen climate classification. Meteorol. Z. 21, 111–123 (2012).

Feng, S., Hu, Q., Huang, W., Ho, C.-H., Li, R. & Tang, Z. Projected climate regime shift under future global warming from multi-model, multi-scenario CMIP5 simulations. Global Planet. Change 112, 41–52 (2014).

Thompson, D. W. J. & Wallace, J. M. Regional Climate Impacts of the Northern Hemisphere Annular Mode. Science 293, 85–89 (2001).

Christensen, J. H. et al. [Regional climate projections]. Climate Change 2007 - The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. [Solomon, S., Qin, D., Manning, M., Chen, Z., Marquis, M., Averyt, K. B., Tignor, M. & Miller, H. L. (eds.)] [847–940] (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge and New York, 2007).

Alessandri, A., Fogli, P. G., Vichi, M. & Zeng, N. Strengthening of the hydrological cycle in future scenarios: atmospheric energy and water balance perspective. Earth Syst. Dynam. 3, 199–212 (2012).

Mariotti, A., Struglia, M. V., Zeng, N. & Lau, K.-M. The hydrological cycle in the Mediterranean region and implications for the water budget of the Mediterranean Sea. J. Clim. 15, 1674–1690 (2002).

Vautard, R. et al. Summertime European heat and drought waves induced by wintertime Mediterranean rainfall deficit. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L07711 (2007).

Held, I. M. & Soden, B. J. Robust responses of the hydrological cycle to global warming. J. Clim. 19, 5686–5699 (2006).

Lu, J., Vecchi, G. A. & Reichler, T. Expansion of the Hadley cell under global warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L06805 (2007).

Fischlin, A. et al. [Ecosystems, their properties, goods and services]. Climate Change 2007 - Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. [Parry, M. L., Canziani, O. F., Palutikof, J. P., van der Linden, P. J. & Hanson, C. E. (eds.)] (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2007).

Meehl, G. A. et al. [Global Climate Projections]. Climate Change 2007 - The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. [Solomon, S., Qin, D., Manning, M., Chen, Z., Marquis, M., Averyt, K. B., Tignor, M. & Miller, H. L. (eds.)] (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge and New York, 2007).

Geiger, R. [Klassifikation der Klimate nach W. Köppen]. Landolt-Börnstein, Zahlenwerte und Funktionen aus Physik, Chemie, Astronomie, Geophysik und Technik, alte Serie Vol. 3 (Springer, Berlin, 1954).

Geiger, R. Überarbeitete Neuausgabe von Geiger, R.: Köppen-Geiger/Klima der Erde. (Wandkarte 1:16 Mill.). Klett-Perthes, Gotha (1961).

Berrisford, P. et al. The ERA-interim archive. Tech. Rep. ERA Rep, Series 1, ECMWF, 16 pp (2009).

Xie, P. & Arkin, P. Global precipitation: A 17-year monthly analysis based on gauge observations, satellite estimates and numerical model outputs. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 78, 2539–2558 (1997).

Morice, C. P., Kennedy, J. J., Rayner, N. A. & Jones, P. D. Quantifying uncertainties in global and regional temperature change using an ensemble of observational estimates: The HadCRUT4 dataset. J. Geophys. Res. 117, D08101 (2012).

Hansen, J., Ruedy, R., Sato, M. & Lo, K. Global surface temperature change. Rev. Geophys. 48, RG4004, 10.1029/2010RG000345 (2010).

Simmons, A. J. et al. Comparison of trends and low-frequency variability in CRU, ERA-40 and NCEP/NCAR analyses of surface air temperature. J. Geophys. Res. 109, D24115 (2004).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the World Climate Research Programme's Working Group on Coupled Modelling, which is responsible for CMIP and we thank the climate modeling groups for producing and making available their model output. This work was partially supported by the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-13) under the grant agreement n. 303208 (CLIMITS project) and under the grant agreement n. 308378 (SPECS project). Lee, Wang and Ha acknowledge support from the National Research Foundation of Korea through a Global Research Laboratory (GRL) grant (MEST 2011-0021927). Cherchi acknowledges the support of the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research and Ministry for Environment, Land and Sea through the project GEMINA. We are grateful to Marta Marcos, Luigi Ponti, Rong Fu and Marina Baldi for the useful scientific discussions and to Gisela Speidel for the English editing of the manuscript. N.Z. acknowledges NOAA grant NA10OAR4310208.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A. conceived the problem, wrote the main manuscript and produced figures 4, S3, S4, S5, S6 and S8. M.D.F. prepared the analysis producing figures 1, 2, 3, S1, S2, S7 and S9 and contributed to the main manuscript. N.Z. and A.M. contributed to conceptualizing the problem and writing the main manuscript. J.Y.L., B.W., K.J.H., P.R. and V.A. contributed to the discussion and writing of the main manuscript. Y.P. downloaded and prepared the data. A.C. performed the analysis of the moisture budget and contributed to the discussion and writing of the main manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Alessandri, A., De Felice, M., Zeng, N. et al. Robust assessment of the expansion and retreat of Mediterranean climate in the 21st century. Sci Rep 4, 7211 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07211

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07211

This article is cited by

-

Asthma incidence can be influenced by climate change in Italy: findings from the GEIRD study—a climatological and epidemiological assessment

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

The impact of climate change in wheat and barley yields in the Iberian Peninsula

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Arid/humid patterns over Asia in response to national-committed emission reductions under the Paris agreement

Progress in Earth and Planetary Science (2020)

-

Climate change over the Mediterranean and current destruction of marine ecosystem

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Mean and extreme temperatures in a warming climate: EURO CORDEX and WRF regional climate high-resolution projections for Portugal

Climate Dynamics (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.