Abstract

Large areas of forests were radioactively contaminated by the Fukushima nuclear accident of 2011 and forest decontamination is now an important problem in Japan. However, whether trees absorb radioactive fallout from soil via the roots or directly from the atmosphere through the bark and leaves is unclear. We measured the uptake of radiocesium by trees in forests heavily contaminated by the Fukushima nuclear accident. The radiocesium concentrations in sapwood of two tree species, the deciduous broadleaved konara (Quercus serrata) and the evergreen coniferous sugi (Cryptomeria japonica), were higher than that in heartwood. The concentration profiles showed anomalous directionality in konara and non-directionality in sugi, indicating that most radiocesium in the tree rings was directly absorbed from the atmosphere via bark and leaves rather than via roots. Numerical modelling shows that the maximum 137Cs concentration in the xylem of konara will be achieved 28 years after the accident. Conversely, the values for sugi will monotonously decrease because of the small transfer factor in this species. Overall, xylem 137Cs concentrations will not be affected by root uptake if active root systems occur 10 cm below the soil.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Fukushima nuclear disaster, caused by the great earthquake and tsunami of 11 March 2011, contaminated vast forest areas with radiocesium: 137Cs at 1.5 × 1016 Bq with 134Cs/137Cs approximately equal to 1.01. Forest decontamination is an urgent issue. Although the internal contamination of trees has been roughly estimated to be small using simple compartment models and a set of parameters2 that takes into account the properties of Japanese forest soil, accurate understanding of how trees absorb fallout 137Cs is required for quick and effective decontamination. To obtain a better understanding of the uptake mechanisms of fallout radionuclides, heavy metals and volatile organic matter in the xylem of trees, we reviewed past studies on radionuclides from the Chernobyl nuclear accident3,4,5,6, nuclear weapons tests7,8,9 and the Nagasaki A-bomb10,11,12, in addition to studies on heavy metals13 and organic material14. A few studies10,11,12,13,14 have suggested the possibility of direct uptake (i.e. not via soil) of atmospheric radionuclides, heavy metals and organic material into the xylem of trees from bark and leaves; however, most studies3,4,5,6,7,8,9 on the Chernobyl accident and nuclear weapons testing have argued that fallout radionuclides are absorbed through the roots from the soil (i.e. root uptake). If atmospheric direct uptake is the main route for absorption of 137Cs into the xylem of trees in Japan, the radiocesium concentration within a tree will decrease with time after the Fukushima nuclear accident. Conversely, if the roots are the main route for radiocesium uptake, 137Cs concentration might gradually increase with a large time lag after the accident, because 137Cs reaches the active zone of roots in the forest soil after a long delay. Herein, we discuss estimates of the possibility and magnitude of direct uptake of atmospheric 137Cs into trees and long-term prediction of changes in 137Cs concentration in tree xylem by root uptake after atmospheric direct uptake.

Results

We measured the vertical profiles of stable and radioactive Cs and K in soil of two tree-harvesting yards at Koriyama, Fukushima, in 2013 (Supplementary Fig. S1). Both 134Cs and 137Cs in the soil are strongly fixed by clay minerals in soil, as shown in Figs. 1a and 1b. More than 99% of the 134Cs and 137Cs deposited from the nuclear accident were trapped in the litter layer and the top 2.5 cm of soil 2.5 years after the accident; their concentrations decrease rapidly with increasing depth. In contrast, 40K and the stable isotopes of Cs and K are almost evenly distributed through the soil profile, except stable K at two depths in the sugi yard.

Vertical concentration profiles of 137Cs, 134Cs, 40K, stable isotopes of Cs and K in soil, 2.5 years after the Fukushima nuclear accident.

(a) the konara yard and (b) the sugi yard. Open blue triangles, red circles, black squares and solid squares and triangles indicate the concentration of 40K, 134Cs, 137Cs and stable isotopes of Cs and K in soil, respectively.

We harvested two Japanese common trees (konara: Quercus serrata Murray, a deciduous broadleaf tree and sugi: Cryptomeria japonica D. Don, an evergreen coniferous tree) to investigate the distribution of 137C, 134Cs and 40K in tree rings in 2012 (Supplementary Table S1). The distributions of 137Cs and 134Cs are almost the same in the rings of both trees. We also measured the concentrations of stable isotopes of Cs and K in tree rings (Supplementary Table S2). We show the distribution of 137Cs and 40K in the xylem in trees divided into four cardinal compass directions in Figs. 2a and 2b. We also demonstrate a directional distribution of 137Cs concentration compared with 40K concentration for konara (Fig. 3a) and a non-directional distribution for sugi (Fig. 3b). In addition, we summarize the directional distribution of radiocesium concentration in the sapwood region of trunk discs in four different directions, verified using the χ2-test, in Table 1.

Radial distribution of 137Cs and 40K measured in annual tree rings in the trunk disc for each of the four different cardinal compass directions.

Results for (a) konara and (b) sugi. Solid squares represent the 137Cs concentration and open circles the 40K concentration. Red, navy blue, olive and turquoise blue indicate the sides of the trunks facing east, north, west and south, respectively.

Using the model proposed in this study, we predict changes in the concentration of 137Cs in tree rings of konara and sugi up to 120 years after the nuclear accident. We show changes in the 137Cs concentration in the xylem with time from the accident (Figs. 4a and 4b), varying the magnitude of the retardation factor15 controlling the migration of 137Cs in forest soil.

Correlations between the 137Cs concentration in soil and tree rings and the elapsed time to 120 years after the Fukushima nuclear accident.

(a) konara and (b) sugi. 137Cs concentration in tree rings estimated when all 137Cs was absorbed from depths of 0 to 20 cm by root uptake alone. Red solid circles and triangles indicate the 137Cs concentration in soil and tree rings, respectively. Coloured lines (black, blue, red, dark blue, pink, navy blue, purple and violet) indicate the magnitude of retardation factors (500, 1000, 2000, 3000, 4000, 5000, 7500 and 10000). The unit of radioactivity is Bq/kg of dry wood or soil.

Discussion

To confirm the occurrence of atmospheric direct uptake into trees, we hypothesized that radionuclides could be absorbed via the following two pathways. First, radionuclides absorbed through the bark could be directly transported into the sapwood, possibly along the ray tissue13,14; if this hypothesis is correct, the radionuclide concentration in tree rings would depend on differences in the directional abundance of radionuclides deposited on the bark surface. In contrast, direct uptake through the leaves of an evergreen coniferous tree would probably show no directionality, because radionuclides transported from multi-directional leaves through phloem sieve tubes would be homogenized by mixing in the sapwood5,13,14. In general, the large canopy of leaves of evergreen coniferous trees effectively traps fallout radionuclides in rain before they reach the bark and the total surface area of leaves is larger than that of bark. If the bark facing a certain compass direction is heavily contaminated with radionuclides before the spring leaf flush, it will be possible to detect significant directionality in the radionuclide concentration in the tree rings of a deciduous tree.

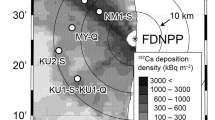

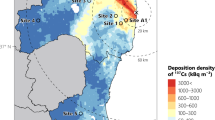

In March 2011, konara in the Fukushima area did not have leaves but sugi exhibited full foliage. Large radio-plumes were released from the accident in the middle of March; later, much radiocesium was transported to the harvesting sites along the mountain range by northeasterly wind and rain during 21–23 March16 (Supplementary Fig. S1). To test our hypothesis, we measured the radial variation of radionuclide and stable isotope concentrations in tree rings in each of the four different cardinal compass directions. The average concentrations of radiocesium in the sapwood of konara and sugi were markedly higher than those in the heartwood region. The radiocesium concentration in the heartwood of konara decreased dramatically from the boundary between the sapwood and the heartwood towards the pith. The concentration of 137Cs in the heartwood appears to lie approximately along a straight line with a steep slope on a semi-logarithmic scale, showing the effect of diffusion (Fig. 2a). However, as shown in Fig. 2b, the profile for 137Cs concentration in sugi was not the same as the pattern in konara. We interpret this as indicating that radiocesium in the tree rings of sugi diffused faster than in konara, possibly because sugi contains more water and has a lower woody density in the xylem than in konara17.

If K, an indispensable element for tree growth, is absorbed primarily through the roots, 40K should also be absorbed by roots together with stable isotopes of K and Cs from the soil. We measured the concentrations of stable isotopes of K and Cs in ash samples from the sapwood and the heartwood of both species (Supplementary Table S2). The measured concentration of 40K is generally low in the sapwood and high in the heartwood. The 40K concentration of both species was uniform and constant in each of the sapwood and heartwood regions in the four different compass directions (Figs. 2a and 2b; Table 1).

For the konara samples, we estimated four ratios (137Csnorth/137Cssouth134Csnorth/134Cssouth, 40Knorth/40Ksouth and stable Csnorth/Cssouth) for the same annual tree rings in sapwood regions facing north and south. Similarly, we also estimated the ratios of 137Cseast/137Cswest, 134Cseast/134Cswest, 40Keast/40Kwest and stable Cseast/Cswest in sapwood facing east and west. These estimates showed that the radiocesium concentrations in the north-facing tree rings are anomalously higher than those facing south. A clear directionality of radiocesium concentration in the sapwood was observed along the north–south section. The contrast between the heterogeneous concentration profiles of radiocesium and the homogeneous concentration profiles of 40K and stable Cs in the sapwood region strongly indicate that the uptake route of fallout radiocesium differs from those of 40K and stable Cs, which is absorbed from the soil via roots (Fig. 3a; Table 1).

Conversely, the ratios of 137Csnorth/137Cssouth, 134Csnorth/134Cssouth, 137Cseast/137Cswest, 134Cseast/134Cswest, 40Knorth/40Ksouth, 40Keast/40Kwest, stable Csnorth/Cssouth and Cseast/Cswest in the same annual tree rings in the sapwood of sugi were almost constant (Table 1). There are no significant differences among these ratios in the sapwood. We could not observe a clear directionality in the radiocesium concentration even if it was present in the sapwood (Fig. 3b), because as previously mentioned, sugi probably had two different routes for direct atmospheric uptake: through the bark and through the leaves. In the case of sugi, the directionality in the radiocesium concentration absorbed through the bark thus appears to have been diluted and concealed by the effect from the multi-directional leaves in the sapwood. These results support our hypotheses: much fallout radiocesium was directly absorbed into tree xylem through short-term atmospheric uptake in 2011.

We observed anomalous directionality in profiles of mobile radiocesium concentration in tree rings of the deciduous tree konara using precise measurements of radioactivity of radiocesium in the xylem. However, this clear directional trace in konara will soon disappear as a result of rapid transport and diffusion throughout the tree. Directional distribution of radiocesium detected using the imaging plate (IP) method, i.e. autoradiography, in 2011 was undetectable in May 201218 due to it being less than the detection limit of the method.

We predicted the 137Cs concentration in the xylem of both types of tree at Koriyama, Fukushima, using the proposed model (Supplementary Information), the average transfer factors of stable Cs estimated for the sapwood region (9.59 ± 2.56 × 10−3 for konara and 8.34 ± 2.55 × 10−4 for sugi; Supplementary Table S2) and direct uptake from the atmosphere (11 Bq/kg for konara and 13 Bq/kg for sugi) in 2011 as the initial 137Cs concentration (Supplementary Tables S3 and S4). Our predictions of root uptake at a depth of 0 cm are that the maximum 137Cs concentration in konara tree rings will reach 120 Bq/kg 28 years after the nuclear accident (Fig. 4a). Conversely, the 137Cs concentration of sugi will decrease monotonously due to the small transfer factor of Cs from the accident. Thus, the atmospheric direct uptake value of 13 Bq/kg plays a vital role in the 137Cs concentration in sugi (Fig. 4b).

Consequently, the absorption effect of 137Cs via root uptake is greater for konara than for sugi. The 137Cs concentration in the xylem of a tree strongly depends on the magnitude of the transfer factor of Cs, deposition rate of radiocesium on the ground surface and depth of the active root system in soil, although the initial effect of atmospheric direct uptake has controlled the 137Cs concentration in the coniferous tree sugi, which has been planted throughout Japan. Our predictions indicate that the 137Cs concentration in the xylem of trees will not be affected by root uptake, if konara does not have an active root system 10 cm below the ground surface. However, further studies of the depths of active root systems in soil are required to estimate the effects of root uptake more precisely.

Methods

Material

Konara was harvested prior to leaf fall at the end of September 2012 and sugi was harvested at the end of October 2012. We used a harvest time of 1.5 years after the nuclear accident to obtain clear data on 137Cs diffusion into xylem. This timing is based on our previous study10 on 137Cs diffusion in French white fir observed at Nancy, France, three years after the Chernobyl accident. We precisely marked each of the four compass directions on the trunks prior to cutting down the trees. After cutting the trees at a height of 1.0 m from the ground surface, we carefully and completely stripped off all bark from the tree trunks over a distance of 45 cm to prevent contamination of the xylem. We cut the trunk vertically into four quarters and then sliced each quarter horizontally into 15 quarter discs, each with a thickness of 2–3 cm. We then separated the tree rings in each quarter disc using a clean chisel for each ring separation to prevent contamination. The separated tree rings were ashed for 20 h at 450°C in an electric oven.

Measurement

The ash samples were then measured for radiocesium and 40K by γ-ray spectrometry using a low-background p-type high-purity Ge-detector (GMX40P4-76, ORTEC, Tennessee, U.S.A.) with 40% relative efficiency and a multichannel analyzer (MCA 7600-000, Seiko EG&G, Tokyo, Japan) with a pulse height analyzer. The instruments were calibrated using the 40K (KCl) method19 and all samples were measured within a period of five days. The detection limits are 0.032 Bq/kg to 661 keV for 137Cs, 0.035 Bq/kg to 604 keV for 134Cs and 0.045 Bq/kg to 1460 keV for 40K. The concentrations of the stable isotopes of K and Cs were measured using an ICP-MS (Agilent 7500cx, Agilent Technology, California, U.S.A.) after the ashed samples were completely dissolved with nitric acid (1:10) using the preparation method in reference 20.

Model

We proposed a model to estimate the 137Cs concentration in the xylem of trees using a root-uptake model that considers the vertical 137Cs concentration in soil and the stable Cs transfer factor from soil to tree xylem with atmospheric direct uptake as an initial condition. We estimate the average 137Cs concentration (Ctree(n)) in the specified entire disc of tree trunk at a height of 1 m above the ground surface using the following assumptions:

The radius of a trunk of tree can be approximated by a cylinder with radius rn (t (time) = n). The elapsed time from the nuclear accident is n.

The radius of the trunk is expressed by the term rn = α × rn-1 after n years from the accident. The growth rate of trunk α is expressed by the following term α = rn/rn-1, (α ≥ 1). The magnitude of α is conservatively 1.013 (Supplementary information and Supplementary Fig. S2). Δr = rn − rn-1 is the width of a tree ring formed in year n.

The initial 137Cs concentration in the xylem of a tree in 2011 is given only by the atmospheric direct uptake; additional 137Cs is provided every year from soil only by root uptake. The 137Cs concentration (Ca) added in the newly formed tree ring is calculated by using the 137Cs concentration (Csoil(n, x)) in soil at a depth of x and the magnitude of the 137Cs transfer factor (Tf(i)) from soil to tree as follows: Ca = Csoil(n, x) × Tf(i). We used the average transfer factors estimated from the ratio (Cstree/Cssoil) of stable Cs concentration in tree rings (Cstree) of the sapwood region to stable Cs concentration (Cssoil) in soil (Supplementary Table S2). The active root system that absorbs 137Cs from soil is only at a specific depth x in the soil. The 137Cs concentration at depth x in soil can be estimated using the one-dimensional diffusion–advection model21,22,23.

The new addition of 137Cs through root uptake is homogeneous every year in the entire xylem of tree as a result of complete mixing with the 137Cs concentration in the tree from the previous year (n–1). The 137Cs concentration in the specified disc of the trunk decreases only by the radioactive decay with the decay constant λ: 0.023 y−1.

The 137Cs concentration (Ctree (n)) is expressed by the following equation:

As the initial 137Cs concentration (Ctree (0)) is given by the atmospheric direct uptake, the 137Cs concentration (Ctree (1)) at the first year (n = 1) can be expressed as follows:

We verified that the proposed model could reasonably predict the 137Cs concentration (Ctree (n)) in the xylem of a tree using data on 137Cs concentration of sugi harvested at Nagasaki in 198810 and that of soil21,22 (Supplementary information, Table S3 and S4). Sugi harvested at Nagasaki showed the effects of both atmospheric deposition from the local fallout after the Nagasaki A-Bomb and global fallout from nuclear weapons testing in the 1950s and 1960s.

References

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan (MEXT). Map of Distribution of Environmental Radioactivity and Radiation by MEXT Doc. 7-1-1, (2011) (http://www.mext.go.jp/b_menu/shingi/chousa/gijyutu/017/shiryo/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2011/09/02/1310688_2.pdf) (accessed 2013.06.12) (in Japanese).

Hashimoto, S., Matsuura, T., Nanko, K., Linkov, I., Shaw, G. & Kaneko, S. Predicted spatio-temporal dynamics of radiocaesium deposited onto forests following the Fukushima nuclear accident. Sci. Rep. 3, 10.1038/srep02564 (2013).

United Nations Scientific Committee on Effects of Atomic Radiation, Report to the General Assembly, with scientific annexes. Annex D. Exposers from Chernobyl Accident. United Nations, New York 1988.

United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation. UNSCEAR 2008 Report to the General Assembly, with scientific annexes. Volume II. Scientific Annex D. Health effects due to radiation from the Chernobyl accident. United Nations, New York 2011.

Fesenko, S. V. et al. Identification of processes governing long-term accumulation of 137Cs by forest trees following the Chernobyl accident. Radiat. Environ. Biophys. 40, 105–113 (2001).

Goor, F. & Thiry, Y. Processes, dynamics and modelling of radiocaesium cycling in a chronosequence of Chernobyl-contaminated Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) plantations. Sci. Total Environ. 325, 163–180 (2004).

Chigira, M., Saito, Y. & Kimura, K. Distribution of 90Sr and 137Cs in annual tree rings of Japanese cedar, Cryptomeria japonica D. Don. J. Radiat. Res. 29, 152–160. (1988)

Momoshima, N. & Bondietti, E. A. The radial distribution of 90Sr and 137Cs in trees. J. Environ. Radioact. 22, 93–109 (1994).

Kagawa, A., Aoki, T., Okada, N. & Katayama, Y. Tree-ring strontium-90 and cesium-137 as potential indicators of radioactive pollution. J. Environ. Qual. 31, 2001–2007 (2002).

Kudo, A., Suzuki, T., Santry, D. C., Mahara, Y., Miyahara, S. & Garrec, J. P. Effectiveness of tree rings for recording Pu history at Nagasaki, Japan. J. Environ. Radioact. 21, 55–63 (1993).

Garrec, J.-P. et al. Plutonium in tree rings from France and Japan. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 46, 1271–1278 (1995).

Mahara, Y. & Kudo, A. Plutonium released by the Nagasaki A-bomb: Mobility in the environment, Appl. Radiat. Isot. 46, 1191–1201 (1995).

Stewart, C. M. Excretion and heartwood formation in living trees. Science 153, 1068–1074 (1966).

Holtzman, R. B. Isotopic composition as a natural tracer of lead in the environment. Comments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 4, 314–317 (1970).

Ohta, T., Mahara, Y., Kubota, T. & Igarashi, T. Aging effect of 137Cs obtained from 137Cs in the Kanto loam layer from the Fukushima nuclear power plant accident and in the Nishiyama loam layer from the Nagasaki A-bomb explosion. Anal. Sci. 29, 941–947 (2013).

Morino, Y., Ohtara, T. & Nishizawa, M. Atmospheric behavior, deposition and budget of radioactive materials from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in March 2011. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L00G11. 10.1029/2011GL048689 (2011).

Kuroda, K., Kagawa, A. & Tonosaki, M. Radiocaesium concentrations in the bark, sapwood and heartwood of three tree species collected at Fukushima forests half a year after the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear accident. J. Environ. Radioact. 122, 37–42 (2013).

Ogawa, H. et al. Distribution and changes of radiocesium concentration of wood in tree trunk of Sugi and Konara. In Proc. The 51st Annual Meeting on Radioisotope and Radiation Research IP-05 (University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan Isotope Association. 2014, July 07) (in Japanese).

Sato, J., Hirose, T. & Sato, K. Application of Ge(Li) detectors to voluminous geochemical samples. Int. J. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 31, 130–132 (1980).

Yoshida, S., Muramatsu, Y., Tagami, K. & Uchida, S. Determination of major and trace elements in Japanese rock reference samples by ICP-MS. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 63, 195–206 (1996).

Mahara, Y. & Miyahara, S. Residual plutonium migration in soil of Nagasaki. J. Geophys. Res. 89, 7931–7936 (1984).

Mahara, Y. Storage and migration of fallout strontium-90 and cesium-137 for over 40 years in the surface soil of Nagasaki. J. Environ. Qual. 22, 722–730 (1993).

Robertson, W. D. & Cherry, J. A. Tritium as an indicator of recharge and dispersion in a groundwater system in central Ontario. Water Resour. Res. 25, 1097–1109 (1989).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research Grant Number 24686098 and the New Technology Development Foundation Grants for the Special Supporting Programs for Reconstruction from the Great East Japan Earthquake. This work was performed as part of the collaboration study between Hokkaido University and Fukushima Forestry Research Center, Fukushima, Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.M. designed this study and performed the field studies, analysed the data and wrote the paper; T.O. performed the experiments, measured the radioactivity, analysed the data and discussed the results; H.O. and A.K. managed and performed the field studies and pre-treated the tree and soil samples.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Mahara, Y., Ohta, T., Ogawa, H. et al. Atmospheric Direct Uptake and Long-term Fate of Radiocesium in Trees after the Fukushima Nuclear Accident. Sci Rep 4, 7121 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07121

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07121

This article is cited by

-

Cellular-level in planta analysis of radial movement of minerals in a konara oak (Quercus serrata Murray) trunk

Journal of Wood Science (2022)

-

Decadal trends in 137Cs concentrations in the bark and wood of trees contaminated by the Fukushima nuclear accident

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Origin and hydrodynamics of xylem sap in tree stems, and relationship to root uptake of soil water

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Tracing radioactive cesium in stem wood of three Japanese conifer species 3 years after the Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant accident

Journal of Wood Science (2020)

-

New predictions of 137Cs dynamics in forests after the Fukushima nuclear accident

Scientific Reports (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.