Abstract

The understanding of protein interactions to control phase and nucleation behavior of protein solutions is an important challenge for soft matter, biological and medical research. Here, we present ion bridges of multivalent cations between proteins as an ion-activated mechanism for patchy interaction that is directly supported by experimental findings in protein crystals. A deep understanding of experimentally observed phenomena in protein solutions—including charge reversal, reentrant condensation, metastable liquid-liquid phase separation, cluster formation and different pathways of crystallization—is gained by an analytic model that directly displays parameter dependencies and physical connections. The direct connection between experiment and theory provides a conceptual framework for future experimental, computational and theoretical research on topics such as rational design of phase behavior and crystallization pathways on the basis of the statistical physics of patchy particles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Patchy particles represent elegant models to explore the statistical physics of soft matter systems with directional interactions, in particular via the Wertheim theory for associating fluids1,2,3,4,5,6. Exploiting different choices of the patch-patch interaction, novel phenomena such as empty liquids7, reentrant network formation8 and control of crystallization pathways9,10 have been found in calculations and simulations. In several theoretical studies, patchy particles have been suggested to be a model system for proteins9,10,11,12,13,14,15. So far the connection between patchy particles and proteins has been based on general considerations concerning the non-spherical shape and inhomogeneous surface patterns of charge and hydrophobicity, as well as on indirect indications such as low density crystals and low critical volume fractions16. Furthermore, single point mutations in the protein sequence have been found to induce significant differences in the phase behavior, suggesting that local variations at the protein surface can change the interaction strongly17,18,19. Recently, a computational study used crystal structures of four mutants of one protein to parametrize a patchy model that successfully reproduced the experimental variation of the phase behavior of the mutants19. These findings demonstrate that the framework of patchy particles is appropriate for proteins. Nevertheless, exploiting the full power of the conceptual framework of patchy particles for control of experimental phase behavior of protein solutions depends on identifying experimental ways to control interaction patches at the protein surface.

Here we present a mechanism for ion-activated attractive patches between proteins that is directly supported by experimental evidence. Our model introduces a novel analytical concept how to account for ion-induced protein interactions by explicitly modeling the role of the cations. This concept can be seamlessly employed in both theory and simulations of patchy particles. Here we use the well-established analytical theory due to Wertheim1,2,3,4,5,6 in order to highlight the essential physics that drives the interesting and rich phenomenology in protein solutions in the presence of multivalent cations.

Multivalent metal cations such as Yttrium(III) form multidentate coordinative bonds with solvent-exposed carboxylic side chains on the protein surface20,21. For globular proteins with negative charge, ion binding is experimentally reflected in a charge inversion of the protein net charge upon the addition of YCl3 (Fig. 1A)22,23. Importantly, multivalent cations cross-link protein molecules in crystals (Fig. 1B)24. These ion bridges represent attractive patches that are activated by cations and can be employed to tune the interactions and the associated phase behavior of globular proteins. Since solvent-exposed carboxylic side chains are ubiquitous in globular proteins, the presented mechanism applies to a large part of the protein family25. Thus, while the control of other interaction patches through e.g. surface patterns of hydrophobicity or charge requires rather involved biotechnological methods such as genetic engineering and structure prediction, the addition of cations allows for activation of patches via a comparatively simple physicochemical experimental procedure.

Ion binding and ion bridging govern the protein interaction.

Experimental observations: (A): Multivalent cations (here: YCl3, cs in mM) cause a charge reversal in protein solutions (here: HSA 5 g/l), evidencing ion binding. The surface charges were obtained as described in Ref. 23. The dashed line corresponds to a Langmuir isotherm (see Methods). (B): In protein crystal structures (here: β-lactoglobulin dimers with Y3+, PDB 3PH624), neighboring molecules are cross-linked by bridges of multivalent ions. For clarity, only 4 of 8 neighboring dimers are shown. Protein model with ion-activated attractive patches: (C + D): The average occupancy Θ (Eq. (3)) reflects the charge reversal. From the ion-bridge energy εuo and the probability for an occupied and unoccupied patch to meet, the ion-induced patch-patch attraction strength εpp (Eq. (5)) results as a non-monotonous function of the chemical potential μs that represents the concentration of free cations.

This mechanism for ion-activated protein interaction is of special interest in the context of phase behavior of protein solutions. In general, additives such as NaCl or PEG are known to induce liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS)13,26,27,28,29,30,31 and solvent-controlled crystallization pathways32,33. Equilibrium clusters have been found in lysozyme solutions34 as expected for charged and attractive colloids35,36 and attractive fluids in general37,38. In these cases, the results are usually discussed invoking unspecific effects such as screened Coulomb interaction or depletion effects. Here, we focus on the addition of trivalent cations that allows via a specific mechanism to control the protein interactions. Trivalent salts such as YCl3 have been found to induce a rich experimental phenomenology in solutions of globular proteins, including reentrant condensation, LLPS (Fig. 2A), cluster phases and one-step as well as two-step pathways of protein crystallization22,24,39,40. Using our analytical model of ion-activated attractive patches by bridges of multivalent cations, the rich phenomenology is explained and understood in a very natural way (Fig. 2B), demonstrating that the concept of ion-activated patches provides a novel and very powerful framework to control the experimental phase behavior of protein solutions. This study introduces the basic mechanism using comparisons to experimental results in protein solutions with YCl3. We emphasize that for a quantitative modeling further effects such as pH variation and electrostatics have to be accounted for explicitly. Although Y3+ is no biologically active cation, the study presents relevant results for the understanding of protein solutions. First, similar results are obtained for several tri- and divalent cations23 such as the biologically active cations Fe3+ and Al3+, implying that ion bridges indeed present a general mechanism. Second, the possibility to activate attractive protein interactions by multivalent cations provides control on phase behavior and pathways of nucleation and crystallization, which is of importance for structural biology as well as an understanding of self-assembly in protein solutions.

Phase behavior of protein solutions with multivalent cations that activate attractive patches on the protein surface.

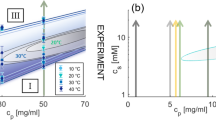

(A): The isothermal phase diagram from experiment (here: HSA with YCl3, replotted from Ref. 39) shows a reentrant condensation for c* < cs < c** and a homogeneous solution otherwise. In the condensed regime, a metastable LLPS is observed. (B): The phase diagram based on the presented model accounts for all experimental observations. The closed LLPS region is indicated as green area. The cluster fraction Φ is shown as orange contour plot, respectively. The connection to the reentrant condensation and physical implications of percolation (red dashed line) are discussed in the text.

Analytical Model for the Activation of Attractive Patches

Within our analytical approach proteins are modeled as particles with m patches per particle. Multivalent cations are modeled as bridge particles, which can bind to a patch and thereby activate it. Other ions are not considered here. The interaction between proteins is given by the hard sphere repulsion VHS between the particles and square-well attractions between the patches1:

R12 denotes the center-to-center distance of the particles.  is the distance between the centers of patch i of particle 1 and patch j of particle 2.

is the distance between the centers of patch i of particle 1 and patch j of particle 2.

The key point of our model is the fact that ion binding controls the attraction strength εpp, thereby representing the activation of interaction patches. The binding sites are considered as independent from each other with binding energy εb. Since a binding site can either be unoccupied (u), or occupied (o) by at most one cation, the average occupancy Θ of each binding site is given by the statistics of a two-state system in the grand canonical ensemble:

with β = (kBT)−1. The chemical potential μs of the salt (s) cations sets the reservoir concentration  . For the concentrations used in the experiments we can approximate this relation via

. For the concentrations used in the experiments we can approximate this relation via  . Note that possible non-idealities of the salt bulk solution do not change the resulting phase behavior qualitatively, but only slightly rescale the relation

. Note that possible non-idealities of the salt bulk solution do not change the resulting phase behavior qualitatively, but only slightly rescale the relation  . We have obtained a comparable behavior for numerical calculations of charged hard spheres, but prefer to use the analytic form of Eq. (3) to allow for an analytic and understandable model focusing on the mechanism of ion-bridging.

. We have obtained a comparable behavior for numerical calculations of charged hard spheres, but prefer to use the analytic form of Eq. (3) to allow for an analytic and understandable model focusing on the mechanism of ion-bridging.

The patch-patch interaction energy εpp is determined from three contributions (see Fig. 1C,D) depending on the average occupancy Θ of two interacting patches:

The first term accounts for the interaction between two unoccupied patches, which meet with a probability of (1 − Θ)2. The second term represents the ion-bridge attraction, when an unoccupied and an occupied patch become cross-linked, with a probability of 2Θ(1 − Θ). The third term describes the interaction between two occupied patches, with a probability of Θ2. In order to recover hard-sphere interaction for fully occupied or unoccupied patches, we choose εuu = εoo = 0. Then εpp reads

Eq. (5) contains the essential physics of our model: the binding energy εb relates to the effective patch-patch attraction strength εpp, thereby expressing the activation of patches with fixed attraction εuo. While the model suggests a clear physical picture of cation binding at specific surface sites and cation bridges, the physical origin of εb and εuo is of minor importance within this framework. In particular, electrostatic contributions and ion-ion correlations between the multivalent cations as well as coordinative binding of metal ions to surface groups can contribute to the energies.

The experimental control parameter is the total salt concentration cs in the system, which is the sum of the ions bound at the surfaces and the free ions in solution. In the model it is more convenient to use the salt concentration in the reservoir  as control variable. The connection between these two quantities is given by

as control variable. The connection between these two quantities is given by

where Rs and Rp are the (effective) radii of salt ions and proteins, respectively. The first term accounts for the ions bound to proteins. The second term originates from the free ions in the solution, corrected for the volume excluded to ions41. The number density ρ is related to the protein volume fraction  .

.

The outlined novel concept to account for the attractive interactions due to ion-bridges can be embedded seamlessly into the Wertheim theory of patchy particles (see Methods). The liquid-liquid and solid-liquid phase coexistence at temperature T follows from chemical and mechanical equilibrium, μ1 = μ2 and P1 = P2, respectively, between phases 1 and 2. The chemical potential μ = ∂f/∂ρ|VT, pressure P = ρμ − f and isothermal compressibility χT = 1/ρ(∂P/∂ρ)−1 are calculated analytically from the free energy densities f of the solid and fluid phase (for further details, see Methods).

As an alternative approach within the Wertheim theory, the proteins could be modeled as particles with two dissimilar types of patches – patch type A, if the binding site is unoccupied and patch type B, if it is occupied. In this case, the average occupancy Θ, Eq. (3), would control the numbers of A and B patches. The protein-protein attraction εpp, Eq. (5), would be generated by the Wertheim theory, for a given interaction between A and B patches of εAB = εuo. We have verified that, while this approach is numerically and theoretically somewhat more involved, it results in equivalent behavior for our system. By presenting the model more explicitly in Eqs. (5)–(6) we wish to highlight the underlying physics of the ion-activated protein interactions.

Model Analysis and Discussion

The main feature of our model is the formation of ion bridges: If an occupied patch interacts with an unoccupied patch, an ion bridge forms and links the participating proteins (Fig. 1D). Based on the attractive interaction induced by the ion bridges, several phenomena in the system become intuitively clear. At low ion concentrations (Θ → 0) the proteins repel each other – in the model by the hard-sphere interaction and in the experimental system through electrostatic repulsion. As more ions are added to the system more binding sites become occupied, i.e. Θ increases, which in the experimental system results in a reduced net charge (Fig. 1A,C). For Θ < 0.5 the addition of ions increases the attraction between proteins, since the probability for an occupied and an unoccupied patch to meet increases. Further increasing the ion concentration (Θ > 0.5) decreases the attraction since too many binding sites are already occupied, thereby reflecting the charge reversal (Fig. 1A,C). At high enough ion concentration, the probability for ion-bridge formation is low and proteins mainly repel each other, corresponding to the reentrant homogeneous phase.

If the attraction is sufficiently strong and the protein volume fraction η is in the right range, a LLPS occurs in a closed area (green line in Fig. 2). Importantly, the low volume fractions of the coexistent liquid phases can be understood with patchy particles, which is not possible using only isotropic potentials42. As expected for protein solutions, the LLPS is found to be metastable with respect to a crystal phase (blue line in Fig. 2B). We find excellent agreement between theory and experiment (Fig. 2).

A natural consequence of the ion bridges is the formation of clusters throughout the entire phase diagram (Fig. 2B). Using the Flory-Stockmeyer theory43,44 the number density ρn of n-clusters and the number fraction Φ of proteins in clusters are given by

With increasing average ion-bridge probability pb, which is provided by the Wertheim theory1 (see Methods), larger cluster become more frequent (Fig. 3A). Thus, with increasing pb, protein diffusion is expected to be reduced substantially due to cluster formation, as indeed observed in recent experiments45. Once pb exceeds the percolation value  , a system-spanning cluster can form, implying that dynamics in the solution is severely slowed down or even arrested.

, a system-spanning cluster can form, implying that dynamics in the solution is severely slowed down or even arrested.

(A): The cluster size distribution  broadens with increasing bond probability (blue lines: pb = 0.0001, 0.001, 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.15, 0.2, 0.25, 0.3; red line:

broadens with increasing bond probability (blue lines: pb = 0.0001, 0.001, 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.15, 0.2, 0.25, 0.3; red line:  ), implying the growth of larger clusters, in particular when approaching the percolation limit

), implying the growth of larger clusters, in particular when approaching the percolation limit  . (B): The integrated scattering power of all clusters, normalized to the monomer solution, shows a steep increase at intermediate chemical potentials μs, i.e. intermediate salt concentrations. This behavior represents one reason for the turbidity in the solution during the reentrant condensation. (C): Another reason for turbidity is opalescence close to the LLPS boundary and the LLPS itself. The forward scattering intensity is proportional to the isothermal compressibility

. (B): The integrated scattering power of all clusters, normalized to the monomer solution, shows a steep increase at intermediate chemical potentials μs, i.e. intermediate salt concentrations. This behavior represents one reason for the turbidity in the solution during the reentrant condensation. (C): Another reason for turbidity is opalescence close to the LLPS boundary and the LLPS itself. The forward scattering intensity is proportional to the isothermal compressibility  , normalized to the hard sphere value, that outlines the reentrant effect. The calculations in B, C are performed for three volume fractions below, through and above the LLPS.

, normalized to the hard sphere value, that outlines the reentrant effect. The calculations in B, C are performed for three volume fractions below, through and above the LLPS.

The formation of clusters provides an explanation for the experimentally observed turbidity in the condensed regime in the concentration range between the boundaries c* and c** (red lines in Fig. 2A). Using the approximation of Rayleigh scattering, the scattering of n-clusters grows with V2 ∝ n2, which causes a steep increase of the integrated scattering power  with increasing pb, in particular when approaching the percolation threshold

with increasing pb, in particular when approaching the percolation threshold  (Fig. 3B). In addition, as the liquid-liquid phase boundary is approached, opalescence causes turbidity in the solution, being manifested in the increase of the isothermal compressibility of the patchy particle solution (Fig. 3C).

(Fig. 3B). In addition, as the liquid-liquid phase boundary is approached, opalescence causes turbidity in the solution, being manifested in the increase of the isothermal compressibility of the patchy particle solution (Fig. 3C).

In protein solutions with multivalent cations, crystals are found experimentally to grow from the dilute phase after LLPS39,40, whereas crystal nucleation should be more favorable in the dense phase according to classical nucleation theory. Although crystallization pathways of patchy particles depends also on dynamical aspects14, two thermodynamic features of our model help to rationalize the experimental observations. First, the dense phase occurs beyond the percolation line and, thus, might be an arrested phase, implying that motions necessary to rearrange from disordered clusters to ordered crystals might be hindered. Second, a considerable amount of clusters is present around the dilute coexistence boundary (Fig. 2B). These clusters might act as precursors in two-step nucleation pathways that occur much faster than the classical one-step nucleation from homogeneous solution40.

The presented framework focuses on the basic understanding of the phenomenology of the ion-bridging mechanism and therefore models the complex experimental system by its essential features in an analytical and accessible description using the Wertheim theory. The analytic approach allows not only to describe but also to understand the phenomena observed in solutions of protein and salt. The mechanism of cation-activated attractive patches can be seamlessly embedded in more detailed theoretical studies and simulations to address multiple questions beyond the present study. First, electrostatics are accounted for in our framework only implicitly by the choice of the effective interaction. Including electrostatics explicitly, the effect of long-ranged repulsion on cluster formation and gelation36 as well as crystallization pathways could be studied. Second, cation–cation correlations as well as dynamical aspects affecting the patch occupation are neglected in the present mean-field equilibrium picture, since the large binding energy of the cations dominates the cation-protein interaction and thus the ion bridging25. However, cation–cation correlations could provide relevant information on e.g. the dynamics and the detailed pathways of protein crystallization10,14. Third, the effect of the geometry of the patch arrangement is not accounted for by the Wertheim theory and is only included implicitly by the choice of the crystal volume fraction (see Methods). An analysis of the ion-bridge mechanism extended towards inhomogeneous patch occupations would be very interesting for a detailed description of the dense and solid phase as well as crystal polymorphs10,24. The presented mechanism thus is the basis for detailed theoretical predictions and presents promising opportunities not only for the study of the protein systems, but also for the general understanding of charged soft matter.

Conclusions

We have presented an experimentally supported mechanism of cation bridges between neighboring molecules as a method to activate attractive patches at the protein surface. This mechanism provides a comprehensive understanding of the experimental observations in protein solutions and allows validation and application of patchy particle models in real protein solutions. The cation concentration represents an independent control parameter, promising rational design and control of phase behavior of protein solutions using multivalent cations and the statistical physics of particles with ion-activated patches. Our model provides a natural analytical connection between experimental results of protein biophysics and the study of patchy particles within the framework of theory and simulations. A natural next step is to extend our model to inhomogeneous density distributions such as adsorption profiles at walls or the free interface between a protein-rich and a protein-poor phase. This can be done either in the framework of classical density functional theory, which allows one to determine density distributions and thermodynamic quantities on equal footing, or with the help of computer simulations.

Methods

Bonding probability from Wertheim theory for patchy particles

The basic result of the Wertheim theory is the bonding probability pb from which the free energy and other properties can be calculated. The bonding probability for m similar patches follows from the mass-action equation1,44

〈fij(1, 2)〉 denotes the average of the Mayer function fij(1, 2) = exp(−βV (1, 2)) − 1 over all relative orientations of the two particles at fixed distance R12. For very short-ranged square-well attraction one can employ the Carnahan-Starling contact value for the pair correlation function gHS(σ) of the hard sphere reference system, in order to approximate Δij analytically1.

Choice of model parameters

For our calculations we set the number of patches m = 4, according to the number of ion bridges per monomer in the protein crystal. The centers of the patches are located within the particle at a distance d = 0.9 Rp from the particle center. Rp = 3.6 nm corresponds to the effective sphere radius46. For the range of the attractive interaction we choose rc = 0.33 Rp, which is sufficiently smaller than the maximum attraction range for our parameter choices

for which hard core repulsion still ensures the condition of only one bond per patch as required for the Wertheim approach.

The ratio between the ion and protein radii is Rs/Rp = 1/18. The bridge energy βεuo = 14 and binding energy βεb = −5 are chosen inspired by the experimental behavior of human serum albumin (HSA) and YCl3 (cf. the Langmuir isotherm Q = Q0 + 3NΘ with N = 6.8, Q0 = −4.4 and βεb = −5.9 in Fig. 1A).

Free energy of liquid phase

The free energy density of the patch bonds between the particles is given by1,44:

with the particle number density ρ = N/V. Both the chemical potential μ and the pressure P of the patchy particles consist of the reference part from the hard sphere system and a part arising from the patch attraction:

Free energy of solid phase

For the solid phase, we used a cell model assuming that all m bonds are formed in a crystal11. The free energy density fc(ρ) is calculated from the restricted volume for free motion Vfree in radial and angular direction at particle distance r11:

The density ρc is given by the volume fraction of a simple cubic crystal  .

.

References

Jackson, G., Chapman, W. G. & Gubbins, K. E. Phase equilibria of associating fluids. Mol. Phys. 65, 1–31 (1988).

Chapman, W. G., Jackson, G. & Gubbins, K. E. Phase equilibria of associating fluids. Mol. Phys. 65, 1057–1079 (1988).

Wertheim, M. Fluids with highly directional attractive forces. I. Statistical thermodynamics. J. Stat. Phys. 35, 19–34 (1984).

Wertheim, M. Fluids with highly directional attractive forces. II. Thermodynamic perturbation theory and integral equations. J. Stat. Phys. 35, 35–47 (1984).

Wertheim, M. Fluids with highly directional attractive forces. III. Multiple attraction sites. J. Stat. Phys. 42, 459–476 (1986).

Wertheim, M. Fluids with highly directional attractive forces. IV. Equilibrium polymerization. J. Stat. Phys. 42, 477–492 (1986).

Bianchi, E., Largo, J., Tartaglia, P., Zaccarelli, E. & Sciortino, F. Phase diagram of patchy colloids: Towards empty liquids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 168301 (2006).

Russo, J., Tavares, J. M., Teixeira, P. I. C., Telo da Gama, M. M. & Sciortino, F. Reentrant phase diagram of network fluids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 085703 (2011).

Whitelam, S. Control of pathways and yields of protein crystallization through the interplay of nonspecific and specific attractions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 088102 (2010).

Fusco, D. & Charbonneau, P. Crystallization of asymmetric patchy models for globular proteins in solution. Phys. Rev. E 88, 012721 (2013).

Sear, R. P. Phase behavior of a simple model of globular proteins. J. Chem. Phys. 111, 4800–4806 (1999).

Kern, N. & Frenkel, D. Fluid–fluid coexistence in colloidal systems with short-ranged strongly directional attraction. J. Chem. Phys. 118, 9882–9889 (2003).

Gögelein, C. et al. A simple patchy colloid model for the phase behavior of lysozyme dispersions. J. Chem. Phys. 129, 085102 (2008).

Whitelam, S. Nonclassical assembly pathways of anisotropic particles. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 194901 (2010).

Haxton, T. K. & Whitelam, S. Design rules for the self-assembly of a protein crystal. Soft Matter 8, 3558–3562 (2012).

Bianchi, E., Blaak, R. & Likos, C. N. Patchy colloids: state of the art and perspectives. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 6397–6410 (2011).

McManus, J. J. et al. Altered phase diagram due to a single point mutation in human γD-crystallin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 16856–16861 (2007).

Buell, A. K. et al. Position-dependent electrostatic protection against protein aggregation. ChemBioChem 10, 1309–1312 (2009).

Fusco, D., Headd, J. J., De Simone, A., Wang, J. & Charbonneau, P. Characterizing protein crystal contacts and their role in crystallization: rubredoxin as a case study. Soft Matter 10, 290–302 (2014).

Harding, M. M. Geometry of metal–ligand interactions in proteins. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D 57, 401–411 (2001).

Yamashita, M. M., Wesson, L., Eisenman, G. & Eisenberg, D. Where metal ions bind in proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 5648–5652 (1990).

Zhang, F. et al. Reentrant condensation of proteins in solution induced by multivalent counterions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 148101 (2008).

Roosen-Runge, F., Heck, B. S., Zhang, F., Kohlbacher, O. & Schreiber, F. Interplay of pH and binding of multivalent metal ions: Charge inversion and reentrant condensation in protein solutions. J. Phys. Chem. B 117, 5777–5787 (2013).

Zhang, F., Zocher, G., Sauter, A., Stehle, T. & Schreiber, F. Novel approach to controlled protein crystallization through ligandation of yttrium cations. J. Appl. Cryst. 44, 755–762 (2011).

Zhang, F. et al. Universality of protein reentrant condensation in solution induced by multivalent metal ions. Proteins 78, 3450–3457 (2010).

Thomson, J. A., Schurtenberger, P., Thurston, G. M. & Benedek, G. B. Binary liquid phase separation and critical phenomena in a protein/water solution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84, 7079–7083 (1987).

Asherie, N. R., Lomakin, A. & Benedek, G. B. Phase diagram of colloidal solutions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 4832–4835 (1996).

Muschol, M. & Rosenberger, F. Liquid–liquid phase separation in supersaturated lysozyme solutions and associated precipitate formation/crystallization. J. Chem. Phys. 107, 1953–1962 (1997).

Annunziata, O., Ogun, O. & Benedek, G. B. Observation of liquid–liquid phase separation for eye lens γS-crystallin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 970–974 (2003).

Wentzel, N. & Gunton, J. D. Liquid–liquid coexistence surface for lysozyme: Role of salt type and salt concentration. J. Phys. Chem. B 111, 1478–1481 (2007).

Möller, J. et al. Reentrant liquid-liquid phase separation in protein solutions at elevated hydrostatic pressures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 028101 (2014).

Wolde, P. R. t. & Frenkel, D. Enhancement of protein crystal nucleation by critical density fluctuations. Science 277, 1975–1978 (1997).

Galkin, O. & Vekilov, P. G. Control of protein crystal nucleation around the metastable liquid–liquid phase boundary. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 6277–6281 (2000).

Stradner, A. et al. Equilibrium cluster formation in concentrated protein solutions and colloids. Nature 432, 492–495 (2004).

Groenewold, J. & Kegel, W. K. Anomalously large equilibrium clusters of colloids. J. Phys. Chem. B 105, 11702–11709 (2001).

Campbell, A. I., Anderson, V. J., van Duijneveldt, J. S. & Bartlett, P. Dynamical arrest in attractive colloids: The effect of long-range repulsion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 208301 (2005).

Sator, N. Clusters in simple fluids. Phys. Rep. 376, 1–39 (2003).

Campi, X., Krivine, H. & Krivine, J. Clustering and thermodynamics in the lattice-gas model. Physica A 320, 41–50 (2003).

Zhang, F. et al. Charge-controlled metastable liquid-liquid phase separation in protein solutions as a universal pathway towards crystallization. Soft Matter 8, 1313–1316 (2012).

Zhang, F. et al. The role of cluster formation and metastable liquid-liquid phase separation in protein crystallization. Faraday Discuss. 159, 313–325 (2012).

Roth, R., Evans, R. & Louis, A. A. Theory of asymmetric nonadditive binary hard-sphere mixtures. Phys. Rev. E 64, 051202 (2001).

Noro, M. G. & Frenkel, D. Extended corresponding-states behavior for particles with variable range attractions. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 2941–2944 (2000).

Flory, P. J. Molecular size distribution in three dimensional polymers. I. gelation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 63, 3083–3090 (1941).

Bianchi, E., Tartaglia, P., Zaccarelli, E. & Sciortino, F. Theoretical and numerical study of the phase diagram of patchy colloids: Ordered and disordered patch arrangements. J. Chem. Phys. 128, 144504 (2008).

Soraruf, D. et al. Protein cluster formation in aqueous solution in the presence of multivalent metal ions – a light scattering study. Soft Matter 10, 894–902 (2014).

Roosen-Runge, F. et al. Protein self-diffusion in crowded solutions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 11815–11820 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank Martin Oettel and Hendrik Hansen-Goos (both University of Tübingen) for stimulating discussions on the manuscript. F.R.-R. acknowledges a fellowship of the Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes. The work was supported by the DFG.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.R.-R., F.Z., F.S. and R.R. designed the research. F.R.-R. and R.R. performed the calculations and analyzed data. F.R.-R. prepared all figures. F.R.-R., F.S. and R.R. wrote the paper. F.R.-R., F.Z., F.S. and R.R. reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Roosen-Runge, F., Zhang, F., Schreiber, F. et al. Ion-activated attractive patches as a mechanism for controlled protein interactions. Sci Rep 4, 7016 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07016

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07016

This article is cited by

-

Effect of Temperature on Re-entrant Condensation of Globular Protein in Presence of Tri-valent Ions

Journal of Fluorescence (2022)

-

Enhanced protein adsorption upon bulk phase separation

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Structure and domain dynamics of human lactoferrin in solution and the influence of Fe(III)-ion ligand binding

BMC Biophysics (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.